8

8

8

8

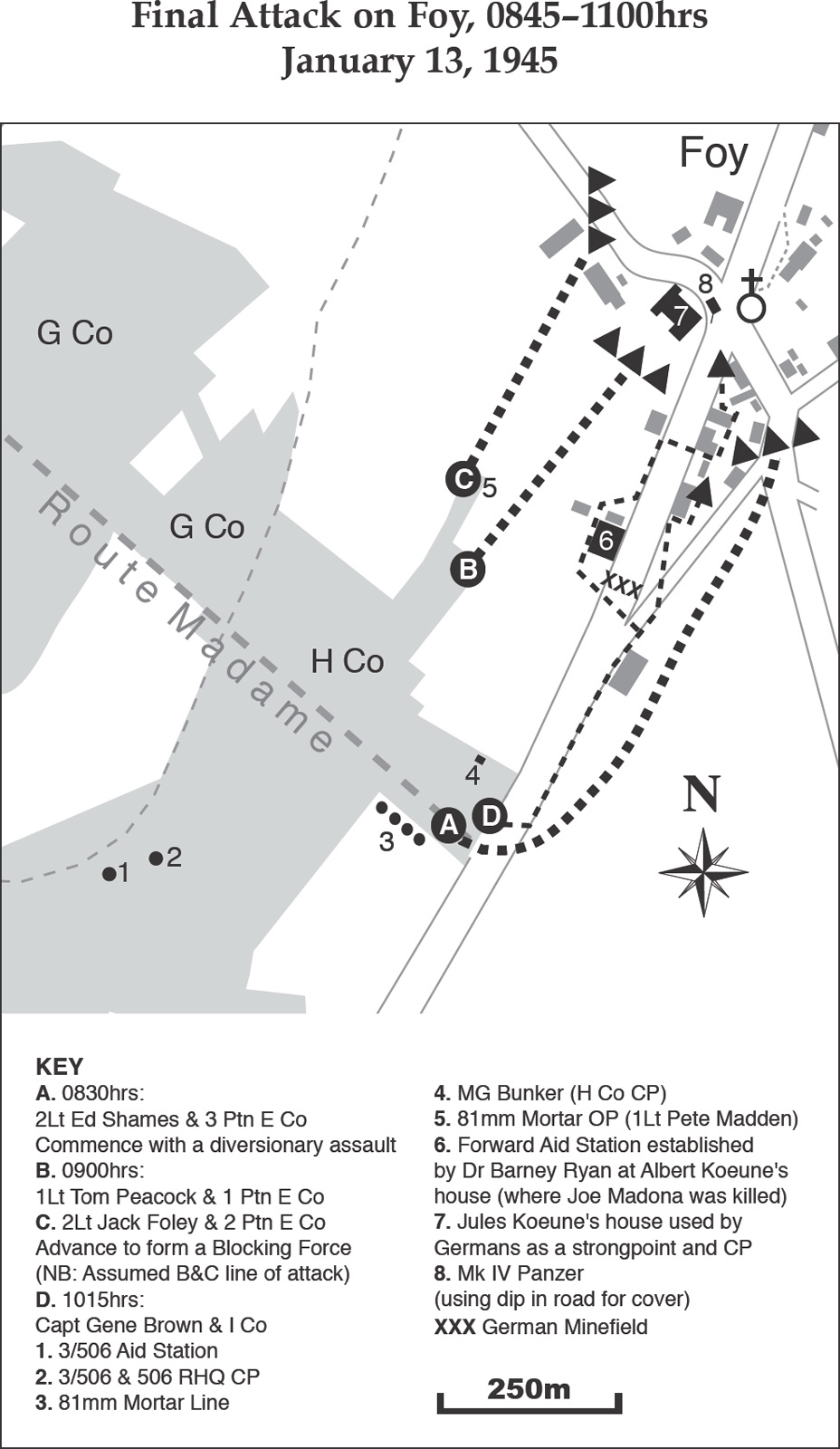

On the evening of January 12, after relieving 401st GIR (who in turn had taken over from the 501st) on the ridgeline at Foy, Col Patch briefed what was left of his officers at the battalion CP in the trees behind the Bois Champay. The idea was to secure the village without damaging the N30 (therefore no artillery was to be used), enabling Shermans and M18 Hellcats from the 11th Armored Division to pass through unimpeded toward Noville. Due to the high number of casualties on January 9, the remaining senior NCOs were shuffled between rifle companies, which, for the most part, were down to fewer than 30 men each with the exception of G Co, which had around 50 soldiers available for duty. What the regiment did not know was that parts of their communications network had been compromised and the enemy were expecting them.

For the first phase, although 2nd Bn were now in regimental reserve behind the MLR, E Co had been attached to 3rd Bn and would join I Co for the attack that was due to begin the following morning. As he had been working so closely with Lloyd Patch, the CO of Regt HQ Co, Gene Brown, was asked to take temporary command of I Co after Andy Anderson had been re-assigned to the battalion staff. I Co were split into two composite squads, the first led by 2nd Lt Roger Tinsley (1 Ptn) and the other (numbering 16 soldiers) by Sgt Harley Dingman, whose platoon leaders, Milo Bush and Don Replogle, had both recently been evacuated.

G and H companies were tasked with holding the line while maintaining fire support along with the 81mm mortar platoon. Alex Andros thought the idea was unworkable due to the lack of available manpower. He recalls: “Other than myself, Capt Jim Walker and 2nd Lt Willie Miller were the only officers remaining in H Co, while I Co were in a worse state than we were. The battalion as a whole was nothing more than an oversized platoon and Patch didn’t really know how he could effectively deploy us, but orders were orders.” During the briefing, 1st Lt Pete Madden was told that he would be providing mortar support to suppress a number of suspected enemy machine-gun positions located on the high ground beyond the village. During the early hours of the 13th, Col Sink relocated his HQ from Hemroulle to the 3rd Bn CP along with reinforcements from Regt HQ Co.

After a night of light enemy shelling the American attack began as planned at 0900hrs, as Madden recalls:

We were waiting for the signal from regiment to commence our fire missions. Several minutes went by but we received no such instruction. By this time, I could see puffs of smoke coming from the German machine-gun nests so we knew they were now actively engaging our troops from E Co who were spearheading the assault.

Suddenly the radio crackled into life: “STAND BY – WAIT – OUT.” Clearly I was familiar with Col Patch’s radio operator, but I didn’t recognize the voice on the end of the line so called for clarification, and the reply came back, “THIS IS KIDNAP BLUE – HOLD YOUR FIRE MISSION.” “What target do you want me to hit first?” I inquired. “JUST HOLD FIRE – THE MISSION IS NO LONGER NECESSARY.” I could still see the smoke from the enemy machine guns up in the woods to the north and couldn’t figure out what was going on. I called back again only to be told, “HOLD YOUR FIRE – THAT IS A DIRECT ORDER.” We knew something was wrong, so I asked for identification. There was a long pause and I repeated the request but received no answer. That was all I needed and immediately called all four batteries onto our pre-recorded targets.

Madden ran back to the battalion CP to advise that the enemy were now tapping into the communications network. Sink had no choice but to order complete radio silence, making command and control during the attack and also over the next few days very difficult.

While Madden had been puzzling over the fire control orders, 1 and 2 platoons from E Co had crossed their jump off point (start line) and were now proceeding down into Foy. Earlier, Ed Shames and 3 Ptn had been sent across the N30 to the extreme western edge of the Bois Jacques (then held by the 501st), where they were supposed to be the lead platoon in a diversionary attack. Shames’ mission was to push down to the crossroad and draw the enemy forces away from the center of town. Simultaneously, at the Bois Champay, 1 and 2 platoons, led by 1st Lt Tom Peacock and 2nd Lt Jack Foley, had emerged from either side of the “Eastern Eye” to begin their advance, keeping the Route de Houffalize on the right. Once into Foy, Peacock and Foley had been ordered to link up with Shames and form a blocking force along a line approximately 300 yards in length, south of the road leading to Recogne.

Ed Shames and 3 Ptn were to employ the same tactic by capturing and holding the other side of the road leading to Bizory. Unknown to the 506th, a German minefield was now covering the N30 at the southern edge of the village. Enemy forces had also established a defensive firebase at the Koeune house. Located at the strongpoint was a mortar fire controller who had all entry routes into the village covered. Several machine-gun crews were located on the upper floors, with uninterrupted views towards the “Eye.” Another gun group operating nearby at Cordonnier Farm had superb fields of fire along the road to Recogne.

The machine guns were also protecting a Mk IV Panzer parked in the dip directly outside the Koeune house. Here the road dropped sharply away, leaving the turret barely visible from the N30. The tank created a formidable barrier and ultimately prevented Shames from linking up with Peacock and Foley. “After arriving at the southeastern edge of the village,” recalls Ed, “we took cover in the shadow of a large tree. At this point we began to receive accurate small-arms fire, and Earl McClung spotted a muzzle flash which came from an upper window of a farmhouse [belonging to Joseph Gaspard] further along the road directly opposite the church.”

McClung dashed forward into the cover of a large stable block that ran alongside the Gaspard Farm, where he heard German voices coming from inside one of the stalls. Firing his rifle through a small window, Earl blasted away at the enemy soldiers before continuing toward his intended target. Stopping a short distance from the sniper’s window, McClung reloaded his rifle with blank ammunition and waited. Moments later a muzzle appeared and Earl fired two carefully aimed rifle grenades into the opening. There is a possibility that the two grenades did not kill the sniper, who was most probably finished off sometime later by another shot from Sgt “Shifty” Powers.

The only serious casualty suffered by 3 Ptn as it skirmished through the southeastern part of Foy was Cpl Frank Mellett. Twenty-four-year-old Mellett was shot dead by a German soldier after entering a house he believed had already been cleared. “Frank’s unnecessary death made me vow to do my utmost to bring every man in my platoon home,” reflected Shames. Beyond the Panzer, over on the other side of the street, Pfc Carl Sawosko from 2 Ptn died after being seriously wounded in the head.

Gene Brown was tasked by Col Sink to lead I Co for the second phase of the assault. He was assisted by Tinsley and Dingman – the idea was to advance down the eastern (right-hand) edge of the N30 and link up with Ed Shames’ platoon at the crossroad. As the only medical officer available, Barney Ryan was attached to Brown along with medics Walter Pelcher and T/5 Eugene Woodside. Shortly after 1015hrs, as Brown’s small force got to within sight of the crossroad, his drive came to an abrupt halt.

Dozens of booby traps had been scattered by the Germans across the N30. Moments later, the leading elements of Brown’s column came under intense machine-gun fire, forcing the men to take cover along the embankment on the left side of the road. Doctor Ryan, who was following behind, received word that a number of casualties were now gathering up ahead around a three-storey house (owned by Albert Koeune). “I decided that this building would become our aid station and ominously upon entering discovered abandoned German equipment, including grenades and a Panzerfaust [antitank grenade launcher] stashed in the kitchen. There were also a number of mattresses lying around which came in useful for the wounded.”

Dead ground

Bypassing the “minefield,” Pvt Al Cappelli (2 Ptn I Co) was sixth in line moving down the edge of the road when the first scout became pinned down by the machine gun from the Mk IV Panzer. From here the road beyond la Vieille Forge (meaning “the old smithy”) dropped away to the crossroad at Foy where the tank was waiting in the hollow outside the Koeune house. Cappelli was called forward and adopted the prone position on the steep snow-covered bank directly opposite a large house owned by the Collard family. “Suddenly I felt a burning sensation in my left knee and looked down to see two blood-soaked holes in my pants.” After being instructed to outflank the Panzer, Cappelli limped back across the road, clutching his bazooka, toward the Evrard house. Moving behind the property and over a connecting footpath, Al found himself virtually opposite the well and close enough to get a clear shot at the tank. The first rocket struck the target (which immediately lost power), but before he could load another round Cappelli was hit again. A few yards away, at the Evrard house, a German soldier with a 9mm Walther pistol was watching from a ground-floor window. “I couldn’t believe that one of the bullets from the P-38 hit me 6in above the wound I’d received moments earlier!”

Lt Tinsley saved Cappelli’s life when he charged the window and killed the enemy soldier. The now-stranded tank was eventually overrun after it ran out of ammunition. Leaving the barrel of their 75mm gun pointing toward Bastogne, the crew evacuated through the rear escape hatches. The turret was later blasted by one of the American TDs, making sure it was no longer serviceable.

A colleague helped carry Cappelli back across the road to the aid station, and with help from Pelcher and Woodside many more casualties were collected and brought in. However, the wounded could not be evacuated by vehicle due to the mines blocking the road opposite the aid post. S/Sgt Joe “Shorty” Madona, who was now platoon sergeant for 2 Ptn I Co, arrived and moved to the rear with Dr Ryan hoping to get a situation report from Capt Brown.

Gene had broken radio silence and was sheltering behind a nearby stone barn. Ryan and Madona listened intently as Brown told Col Patch that I Co had hit a “hornet’s nest” and he needed immediate back up. As Madona and Ryan walked back toward the doorway they were hit by a sudden burst of machine-gun fire. “It felt like I’d been struck in the chest with an axe,” recalls Ryan. “S/Sgt Madona was killed instantly and crumpled to the floor. The burst ricocheted off the solid stone frame surrounding the door, striking me in the chest and Joe (who was much smaller than me) in the forehead.”

Later Madona was awarded a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Bastogne. He had developed into a fantastic leader and was greatly admired by everyone, especially Ed Shames, with whom he had been best friends since the early training days in the USA.

“I felt myself breaking into a cold sweat,” recalls Ryan, “and although weakened, I managed to walk into the house and lie down beside the others. Blood had begun to trickle down my back as Woodside cut away my British tanker overalls (given to me on January 9 by Charlie Shettle) and applied a Carlisle bandage. Surprisingly there wasn’t that much pain, so I refused morphine.” Shortly afterwards, Ryan sent word to Capt Brown, who notified the regiment that the battalion needed another medical officer and Louis Kent was sent forward to keep things under control.

Unbeknown to Ryan, four Germans had been trapped in the cellar when he occupied the house. Uncertain of what to do next, the enemy soldiers remained silent as blood from the wounded lying on the floorboards above began to drip through the cracks. In the darkness one of the young Volksgrenadiers started to panic and knocked over a shelf. “On hearing a German voice, Walter Pelcher sent someone down into the basement with a weapon, and 30 seconds later the four young men appeared with their hands raised in surrender,” recalls Ryan. “I heard someone say, ‘Let’s shoot the bastards.’ ‘Hell no,’ I screamed. ‘We’ll use them to carry the wounded back up to the MLR’ (no doubt thinking of my own self- preservation at the same time!). Pelcher put the prisoners to work carrying the more severely wounded out on stretchers through roadside ditches to a hastily organized jeep collection point.”

Ryan was taken to Bastogne before being evacuated by ambulance to the 60th Field Hospital at Neufchâteau. By the time he arrived, Barney was in deep shock and underwent immediate surgery. “I awoke the next morning to find myself under the care of an old classmate from medical school, Larry Kilham, who presented me with a battered 7.92mm bullet that the surgical team had removed from my lung.”

Last gang in town

On the MLR, at around 1100hrs that same day, just like a scene from the Alamo, Bob Sink and Lloyd Patch ordered Andy Anderson and Jim Walker to gather all available spare manpower and join forces with 1 Ptn F Co to relieve the pressure on Gene Brown. The enemy shelled the woods while the composite group was being assembled behind the “Eye” on Route Madame. The intense barrage delayed the relief mission and wounded several people, including S/Sgt Richard “Red” Falvey from HQ Co 2nd Bn. Shortly before the relief force left the woods, Capt Dick Winters (who had just taken over as 2nd Bn XO from Charlie Shettle) ordered 1st Lt Ronald “Sparkey” Speirs to go on ahead with a handful of troops to personally inform Norman Dike what was about to happen. At the time Speirs, formerly with D Co, was temporarily un-assigned. However, steel and fortitude were now needed and clearly “Sparkey” was the best man for the job.

After being attached to 3rd Bn, F/506 took over the positions vacated by H Co as Walker ordered Alex Andros to take 3 Ptn and make a flanking movement across the N30 along the outskirts of the village (the same route previously taken by Ed Shames and his men). Walker then split his 1 Ptn equally on either side of the main road and was about to move out when Fred Bahlau ran over to offer assistance. Moving forward, the men passed a dead German frozen in the snow, who looked like some ghoulish form of traffic calming measure. Before reaching the edge of the minefield, Walker’s team came under heavy artillery fire and ran for cover.

Down in Foy it was complete chaos – Brown and Tinsley were now desperately trying to coordinate I Co, who numbered fewer than 20 men, including replacement Pvt Alvin Viste: “Our ‘squad’ was on the right flank next to H Co, when we came up against stiff resistance from a machine gun near the aid station, which was now clearly marked by a large Red Cross. There was another German MG firing from a nearby farm building. Using our light machine gun, Cpl Wilbur Fishel began pouring fire into the enemy position until his weapon jammed due to a stoppage in the feed tray. To enable Fishel to safely sort out the malfunction, Florensio Valenzuela and I agreed to swap positions with him. As we began to move forward, a mortar shell exploded on the spot I had just vacated, killing Valenzuela (who was just behind me) and seriously injuring Fishel.”

Nowhere was safe from enemy machine-gun fire, and without Harold Stedman around to watch his back, Cpl Jim Brown was killed after being struck in the left eye. Both Cpl Harry Watson and Pvt Wayman Womack (Harold’s Number Two on the 60mm mortar) were badly wounded, and T/5 Gene Kristie and Pvt Howard Cleaver captured.

After Joe Madona was killed, Alvin Viste and his squad overran the enemy machine-gun team who then tried to surrender, as Viste recalls: “Pumped up with anger we took no prisoners and finished the crew off with our trench knives. We then began to work our way toward the aid station, joining with other troopers from H Co who were now coming in from the east, where, for most part, the cleansing action was complete. While clearing one of the buildings we came across a German sitting bolt upright in a chair and fired several rounds into him before noticing that the guy was already dead. ‘Dopey,’ our company runner, burst out laughing and it was then we realized it was a sick joke … needless to say the rest of us weren’t very amused.”

As I Co were still attempting to clear the houses along the southern edge of town, 1st Lt Alex Andros and his men were halfway around Foy. Earlier the main relief group led by Andy Anderson, including 2 Ptn H Co and 1 Ptn F Co, headed down into the village from the Bois Champay. Hindered by the radio lockdown, Anderson became embroiled in crossfire with E and I Co plus the enemy machine guns based at Koeune and Cordonnier farms. Both companies were now under heavy mortar fire and struggling to maintain their individual missions. Something had to be done before somebody was killed by friendly fire. Taking a deep breath, Speirs ran across open ground and spoke directly with Roger Tinsley, who immediately instructed his men to stop firing. As Speirs was returning to E Co he looked around and saw Tinsley hit by a burst of enemy machine-gun fire.

Just up ahead, Fred Bahlau, who was now with the H Co group, could see the medical collection point close to the southern edge of the minefield and watched as two men from 326th Airborne Medical Co loaded an evacuation jeep with wounded. As more shells began to explode, one medic dashed into a nearby house, while the other hid under the jeep leaving their two wounded charges strapped helplessly on stretchers. “Incensed, I ran over and kicked the guy cowering underneath the vehicle and jumped into the jeep,” recalls Bahlau. Driving back up the road away from the danger area, “Fast Freddie” was flagged down by six men from I Co who asked if he would be kind enough to evacuate Roger Tinsley.

Being a recent replacement, the young officer was unfamiliar to Fred. Tinsley’s combat jacket was hanging open and Bahlau could see a steady stream of blood pulsing from his chest. Tinsley had also been hit in the head, but at that moment in time it seemed the least of his worries. The chest wound was quickly sealed and dressed before Tinsley was leant across the hood. Bahlau instructed two of the lieutenant’s men to climb onto the jeep and hold their platoon leader down before heading to Bastogne – where, the following day, 2nd Lt Tinsley died.

During the next hour or so, 1 Ptn from F Co played a vital role in mopping up. This was illustrated by the fact that 2nd Lt Ben Stapelfeld, who had been deafened by concussion, personally dispatched two enemy soldiers hiding in a cellar. Further east, 3 Ptn H Co came under heavy shellfire near the church. “I concluded that the rounds must have come from a wooded area we could see in the distance,” recalls Alex Andros. As 3 Ptn maneuvered to envelope the buildings on the western side of the road, the intense shelling suddenly lifted. Realizing the enemy must have been communicating with their own artillery from the basement of Jules Koeune’s house, “Dud” Hefner moved forward past the Panzer (which had been abandoned earlier) with a couple of men. Hefner approached the property and fired a burst from his submachine gun through one of the 2ft-wide slit windows near the entrance.

Hearing the challenge issued by Hefner, the enemy troops sheltering in the cellar moved back to another compartment, as the bullets tore into the wall and ricocheted across the ceiling adjacent to the door. “Moments later, around 20 Germans emerged, hands on heads, and surrendered. As we double-timed the prisoners back to a temporary compound, our medic, Irvin ‘Blackie’ Baldinger (who spoke German), came over and told me that one of the younger Krauts was being particularly difficult and kept swearing at me. I wasn’t in any mood for this nonsense and ran over to the kid, cocked my Thompson, and tapped a few rounds into the ground around his feet. I’m pleased to say he sprinted away like his life depended on it … and truthfully it probably did.”

Later in the afternoon Alvin Viste encountered a couple of unidentified civilians who were protesting about what they thought was indiscriminate American gunfire during the attack. “This was totally untrue and I believe that these people, whoever they were, may have actually contributed toward the deaths of my comrades. At that point I felt that there were far too many troops milling around and decided to move away and find cover before we all became a target for further enemy mortar fire. Not long afterwards I learned that Cpl Fishel had been dragged to safety and subsequently evacuated.”

2 Ptn H Co had cleared one particular house and were now using it for an OP. It would appear that after the village was back in American hands, radio silence was briefly lifted, as Frank Kneller recalls: “Two hundred yards or so further to the north, we observed smoke rising from the chimney of a small farmhouse. Within seconds, I’d been patched through via our phone network to the Air Force. To me, as a lowly 7745 [payslip code for a private soldier], it seemed amazing that I was now talking directly to the pilot of a P-47 Thunderbolt circling overhead.” Kneller tried his best to direct the aircraft toward its target but the last bomb fell short and blew him down a flight of stairs.

The wrecks of several burnt-out German tanks and fighting vehicles lay scattered through Foy. Although the Germans continued to shell the village the area was now clear of enemy troops. In total around 70 prisoners were taken during the 7-hour operation. By 1630hrs, shortly after 3rd Bn regained control, E Co returned to 2nd Bn, leaving H and I companies in defense, with F Co on the far northeastern edge of the village.

At this point Norman Dike was promoted and Ron Speirs given charge of E Co. F Co were now firmly connected to the left flank of 3/501 (along the old drover’s road), who were still occupying the Bois des Corbeaux. H Co secured an area around the center of the village, while I Co held the northern approaches near the two concrete bunkers on a line between the properties belonging to Leon Dumont and Joseph Bastin. Lou Vecchi recalls a few of his guys from 1 Ptn sheltering inside the church for warmth, which was one of only a few buildings left standing that still had a roof.

Later on the afternoon of January 13, the remainder of the wounded were evacuated. Behind Joseph Gaspard’s house on the eastern side of the main road, Alex Andros discovered a ruined barn containing dozens of frozen corpses, both American and German. “I suppose the Krauts must have used the place as a temporary morgue, but what took me by surprise was the way in which the bodies were so neatly stacked and separated.” Ralph Bennett remembers seeing a number of starving pigs feasting on recently deceased German bodies.

Under cover of darkness the assault pioneers cleared the main road of mines to make way for the Sherman TDs and Hellcats from 11th Armored. F Co established its CP at the Evrard house and set up a defensive line facing east toward Bizory. Adjacent to the “minefield” in the back garden of Marcel Dumont’s house, the engineers made a gruesome discovery. The bomb squad came across the corpses of Héléne Gaspard and her two-year-old son Guy in makeshift coffins. Héléne and Guy had been killed by shellfire almost three weeks earlier. Despicably, their frozen corpses had been booby-trapped by the Germans.

Lift up thine eyes – January 14, 1945

All three remaining companies (F, H, and I) prepared to spend a cold night in Foy. The remains of the village seemed peppered with abandoned enemy trenches and defensive positions full of lice and human feces. That night, on the northern edge of town, Alex Andros was trying to get some rest in a barn behind one of the farmhouses when Pfc Tom “Pat” Fitzmaurice, who had been on outpost duty, informed him that he could hear enemy armor gathering on the edge of the village: “I grabbed a couple of guys and went forward with Fitzmaurice to the OP and sure enough we could hear about four enemy tanks trundling around no more than 50 yards away. For some reason the crews decided to open up with machine guns but every round they fired went way above our heads.” The German tanks were attempting to draw fire and ascertain American strength. Andros reported the build-up and before the regiment had a chance to react, German artillery activity began to intensify.

Around 0415hrs the enemy counterattacked with six tanks, each supported by six or seven infantrymen who bayoneted every foxhole they came across. Emile Dumont’s house (on the northeastern edge of town) had become the CP for 1 Ptn F Co. Ben Stapelfeld and one of his NCOs, John Taylor (who was later awarded the Silver Star for his actions), were watching a side road from the kitchen window when they saw a tank and around 12 infantrymen heading their way. After a brief exchange of fire (which killed four enemy soldiers) Stapelfeld and his colleagues escaped through a rear window and made their way back to the church where they hooked up with H Co.

Sgt Harley Dingman was ordered to report to the forward CP, located near the crossroad, most probably at the Gaspard house. As Dingman walked in, Gene Brown, Jim Walker, and Alex Andros were weighing up their options. After a brief discussion Brown told Dingman in no uncertain terms that he was volunteering his eight-man squad to cover a controlled withdrawal. “It wasn’t up for discussion,” recalls Harley. “The rifle companies were then ordered to bring all their remaining ammunition and medical supplies to the CP.” After Dingman and his squad had “bombed up,” he split his men into four two-man teams and deployed them on a line in the Wilkin, Gaspard, Koeune, and Cordonnier houses. Over the next 2 hours, under cover of darkness, the men kept up a continuous volley of small-arms fire as Dingman ran from house to house shooting into the air. “I had my guys moving between windows firing randomly on a low trajectory toward the oncoming threat,” recalls Harley. “The diversionary rearguard action worked and fooled the Germans into thinking we still had a sizable combat presence in the village.” However, this did not stop the enemy tanks from carefully advancing in parallel down the N30 and along a side road leading into Foy.

Gene Brown received orders via runner (as the regiment was back on radio silence) to withdraw and reorganize with 2/506 up on the ridgeline. 2nd Bn had been ordered forward to take up positions extending from the 3rd Bn CP in the Bois Champay to the N30. At the same time the first American tanks began to move down into Foy. “As it started to get light we began to exfiltrate but still kept up the rifle fire until we were out of the village,” recalls Dingman. Harley was later awarded the Silver Star for his courage, leadership, and initiative during the mission, which gained some vital time for the 506th. He adds, “After what was left of my patrol regrouped back on the MLR, I looked into their haggard faces and felt momentarily overwhelmed by the terrible responsibility of leadership.”

Earlier, just before 1 Ptn H Co withdrew, Lou Vecchi received last-minute instructions to abandon his line of precious 60mm mortars. “To leave the tubes in situ seemed a ridiculous idea, so I decided to remove each C2 sight and throw it as far away into snow as possible. At this point, Tom Beasley came running over in a panic, shouting, ‘Cpl Myers is dead!’ I couldn’t believe what he was saying because I had only spoken to Luther a few moments earlier. After disposing of the sights, I went to check on Myers, who thankfully was still very much alive after being hit by shrapnel.”

A few hundred yards away to the west the forward sector occupied by G Co had also received some attention from the enemy, as Jim Martin recalls: “At around 2300hrs, 2 Ptn (who numbered about 26 men) were on OP duty 1,000 yards in front of the ridge when two enemy tanks supported by infantry pushed into our area, and the firefight continued deep into the night. Illuminating rounds fired from the 81mm mortar line up on the MLR kept troop movement to a minimum. A Sherman TD came trundling down the hill in the darkness and began spraying the enemy with heavy machine-gun fire. When the tracer rounds started to ricochet at right angles into the air, the TD crew knew that they had located the lead enemy tank.”

Seconds later, the Sherman fired two rounds in rapid succession, both of which deflected upwards after striking the glacis plate of the German tank, directly below the front turret. “Bizarrely, as the first shell left the barrel it was followed by a luminous green smoke ring that slowly disappeared before our eyes,” recalls Jim. The lead enemy tank returned fire, knocking out the TD. Another Sherman rolled up and pumped a couple of rounds into the first tank, which immediately caught fire. At this point the second German tank opened up on the newly arrived Sherman and disabled its turret before withdrawing. Jim Martin continues:

It looked to us like the bedrolls strapped to the side of the German vehicle had caught fire, ignited by sparks from the other tank.

Although it became a kind of stand-off we could clearly hear the sounds of more enemy armor building up in the distance. As it began to get light we spotted one of the tanks from the night before parked up about 75 yards in front of our positions. The remaining Sherman TD had moved away in the early hours toward Foy, which, despite the fog, left us vulnerable and exposed. If we were going to get out in one piece we had to do something.

1st Lt Rowe called me over to his foxhole and said, “Martin, I’ll put you in for a Silver Star if you’ll go out there and plant a demolition charge under the tank.” “Lieutenant,” I replied, “are you crazy? Sergeant Anderson and I will put you in for one if you go.” Rowe wasn’t impressed and gave me permission to call in smoke to mark and record the surviving enemy tank and also the approximate position of the German troops who were in the trees opposite. The first rounds fired for effect landed accurately, so we gave the artillery boys permission to go ahead and send in the 155mm HE. Around 0600hrs, when we were certain the enemy were pinned down, Lt Rowe gave the order to withdraw. I’ve never been so scared, and luckily, despite coming under random small-arms fire, nobody was seriously injured as we ran back through the mist toward the “safety” of the MLR.

Dawn was breaking as H Co moved out of Foy in extended line. “As the fog was clearing,” recalls Alex Andros, “I happened to look round and saw Fitzmaurice (who had been on OP duty) about 300 yards away slipping and sliding up the slope trying to catch up with us. It transpired that despite my clear verbal instructions nobody had told him we were leaving!” Up on the ridge Pete Madden was attending an officers’ meeting at the battalion CP. “Afterwards, as I was preparing to return to the mortar line, I bumped into one of the cooks I knew from HQ Co, Sgt Tony Zeoli, and stopped for a quick cup of coffee. As we were talking a shell exploded in the trees and a piece of shrapnel tore through Zeoli’s groin and kidneys. Another fragment hit me in the upper chest but luckily was stopped by a box of C-rations in my top pocket.”

Bob Dunning happened to be there at the time and recalls, “It looked like Zeoli’s penis had been injured and he was screaming over and over that he’d been ruined for life. We really didn’t like Zeoli, whose nickname was ‘Blackass,’ and as Doctor Kent was taking him back to the regimental aid station, one of our replacements, Charlie Smith, called after him and said, ‘Don’t worry Sarge, the Doc might be able to cut off a piece of your nose (which was pretty large) and replace your pecker with it!’ He didn’t appreciate our humor and disappeared into the distance shouting abuse with all the venom he could muster.”

“After Zeoli was sent off to the hospital,” recalls Pete Madden, “another barrage came in and shrapnel rained down all over the place. I crawled under a Sherman tank that was parked nearby and lit up a cigarette. In the middle of the barrage the tank drove off toward Foy. I sprinted to my CP, which was covered with heavy logs. Ironically, as I entered the bunker, a piece of shrapnel came flying through the entrance and tore into my knee. The wound was serious enough for me to be evacuated to Paris. After the splinters of metal were removed from behind my patella I was shipped to a hospital in the UK.”

2nd Bn were diverted to an assembly area in the woods above Recogne in preparation for a hastily organized attack on Cobru, which they subsequently secured. With Allied armor now consolidating in Foy and Recogne, the last few remaining enemy tanks were destroyed.

What was now left of 3rd Bn was ordered northwest to the southern edge of Fazone near the lake to make contact with 1st Bn and the 17th Airborne (who were scheduled to take over from the 101st), as Alex Andros recalls: “We marched through deep snow in single file and upon reaching the woods came under artillery bombardment. The barrage seemed to originate from somewhere to our rear so we knew it had to be friendly. About half a dozen rounds exploded before someone realized they had made a mistake but not before one of our replacements was badly injured. I don’t think the new guys reacted in the same way we did to counterfire. Maybe they froze for a few extra seconds… I mean, we were still just as scared but somehow those of us who had survived one or more campaigns seemed to instinctively know what to do.”

Due to the shelling G Co suffered four casualties when Pvt Franklin Ely was killed and privates Abner Liggett, Chester Shaffer, and Tim Clifford were seriously wounded. With 2nd Bn now in control of Cobru, E Co moved forward to the high ground on the southeastern edge of Noville between D and F Co to maintain the regimental front – which was once again under radio silence.

Guts and drive – January 15–20, 1945

After digging in for the night, 3/506 relocated to the northeastern edge of Fazone Woods, where they had previously suffered so much damage during “Hell Night.” The battalion re-occupied the fortifications recently vacated by 1/506 – now in the process of attacking and capturing a wooded area directly northwest of Cobru. During the “cleansing” action, Capt Roy Kessler was killed leading A/506. Kessler had been seriously wounded in Holland when he was XO for H Co. As 2/506 were attacking Noville, Col Sink moved forward and relocated his CP to the Château d’Hoffschmidt in Recogne, which had only recently been cleared by S/Sgt Keith Carpenter and the regimental demolition platoon. Back in Bastogne the town was still under intermittent attack by the rail gun, which had an effective range of over 11 miles!

On January 14, two platoons from E Co and one from F Co took cover for the night in an old, abandoned quarry overlooking the church at Noville. The quarry pits were covered with logs and anything else that could be found for protection. A dawn attack was planned for the following morning that would simultaneously coincide with 1st Bn’s assault into the woods directly northwest of Cobru. During the premission briefing, carried out by Capt Winters and 1st Lt Speirs, 1/Sgt Carwood Lipton was tasked to take 2 Ptn (because Jack Foley had been wounded at Foy) and clear the western (left-hand side of town), while Ed Shames and 2nd Lt Ben Stapelfeld (1 Ptn F Co) were to come in from the east. Still under radio blackout, the force was told to expect support from 11th Armored, who were operating a number of M36 “Jackson” tank destroyers that had only just arrived in theater. With its low silhouette, the Jackson, weighing 29 tons, was fitted with a long, 90mm gun complete with a muzzle brake. At a glance it could quite easily be mistaken for a German Mk V Panther.

Pfc Jay Stone and Sgt Plummer from 321st GFA were attached to 2/506 for the assault albeit in different FO parties. There was no evidence to suggest that the 321st communications network had been breached, so the two groups were able to provide the artillery and close air support vital to the assault. Because the church was so badly damaged the enemy were unable to use its steeple as an observation post. For this reason 2 Ptn were able to move forward to a fence line from where Lipton could just make out the rear of several large properties situated on the western side of the main road.

As the buildings seemed unoccupied, Lipton carefully advanced with his radio operator (probably tuned to the 321st network) to a barn from where they could clearly observe the N30. From here it was just about possible to make out the outline of a Sherman and a half-track. Thinking 11th Armored could already be in town, Lipton decided to patrol toward the crossroad for a closer look. Trying hard not to disturb the frost-covered snow, Lipton picked his way into town only to find that the American vehicles had been knocked out on December 20 during Team Desobry and 1st Bn’s epic withdrawal. Fearing the worst, he decided to pull back and report his findings to Speirs.

____________

Shortly before first light the assault platoons moved out to their respective jump-off points. Ed Shames crossed the N30 with 3 Ptn ahead of Ben Stapelfeld and moved his men into position behind the Beaujean house (previously the 1st Bn aid station on December 19/20) situated on the southern edge of Noville. Once again, the job for 3 Ptn was to punch toward the center of town and consolidate behind the church and await further instructions. Shames was somewhat concerned by the amount of exposed ground he and his men would have to cross before even reaching the church. In front of 3 Ptn, about 300 yards away on the other side of the field, was a line of trees that ran toward the back of the church and presbytery. Beyond the trees was a small group of buildings that included the milking shed belonging to Felten Farm.

Almost immediately 3 Ptn came under artillery fire. The shelling seemed to be coming from a nearby area of woods that overlooked the town from the northwest, as Ed Shames recalls: “I watched the shells come in and start to explode on a line, one by one, in front of us. As they dropped closer I thought, ‘This is it; I’m dead,’ but the last shell in the salvo failed to detonate and was still fizzing in the deep snow as we passed by.” 2 Ptn encountered less resistance as they were partially protected by buildings but still lost Pfc Ed Joint (1st Squad) and Pfc Brad Freeman (60mm mortar squad), who were both wounded.

Quickly gathering momentum the platoon reached the tree line on the far side of the field and took refuge in the milking shed behind the church. After a brief respite, 3 Ptn went on the offensive and skirmished around the barn, neutralizing the few remaining pockets of enemy resistance as a flight of P-47 Thunderbolts arrived overhead. The attack ended as quickly as it had begun, with the enemy withdrawing northeast, leaving the area around the church clear. Minutes later Ed was somewhat surprised when a message came through on the radio: “Friendly armor on the right.” “Shortly afterwards,” he recalls, “we heard a terrific rumbling noise and I asked my radio operator Pvt Jim ‘Moe’ Alley to go outside with me and make contact.”

So as not to become targets for the P-47s and because radio silence was still officially in force, the two men decided to leave their helmets, rifles, and equipment behind before walking around the corner into Route de Bourcy. Shames and Alley headed down the road a short distance to the crossroads, passing the stone wall belonging to the presbytery on their left. Upon reaching the main road, Shames looked both ways but saw nothing except for the Sherman, a German Stug SPG, and the half-track knocked out in December outside the church. Then Shames noticed the back of another tank parked between two gutted buildings on the right-hand side of the street in the direction of Houffalize. Thinking this might be one of the new M36s, Alley ran on ahead and yelled out a greeting to its commander.

As the two paratroopers approached they could now clearly see the NCO standing in the turret. As the man turned around, Shames and Alley stopped in their tracks. The tank was not an M36 but a Panzer V armed with a powerful 75mm gun. It would appear that the vehicle and its five-man crew had been left behind, possibly due to some sort of communications breakdown.

The enemy tanker panicked and immediately attempted to traverse his turret toward Shames and Alley. “It was a terrifying moment as we turned on our heels and ran for our lives,” recalls Shames. The tank reversed out and lurched forward in pursuit, firing its 7.92mm machine gun as the two men sprinted back toward the presbytery. Helpless over on the other side of the street, 2 Ptn looked on, open mouthed, while the 46-ton behemoth chased down their comrades. As the tank (which had a top speed of 38mph) was turning into Route de Bourcy, Shames and Alley took a leap of faith over the 5ft-high presbytery wall, which, luckily for them, tapered at that point into a small embankment. No more than a second later, as the Panzer turned the corner, it fired into what was left of the building before continuing westwards toward Bourcy. The concussive blast of the gun made everything shudder, and the resulting explosion lifted Shames and Alley bodily off the ground.

Ben Stapelfeld’s 1 Ptn from F Co had been attached to E Co for the assault. Ben led his men in behind 3 Ptn, past a burned-out Mk IV Panther, toward the graves of the eight civilians murdered by the SD on December 21. Ben and his men were pinned down by enemy machinegun fire and forced to take cover in a nearby pigpen. Cpl Robert Stone was ordered by Stapelfeld to fire his 60mm mortar onto the enemy tank as it moved along the road toward Bourcy. Ben hoped that one of the shells might hit the commander but it was futile. Just when they were about to give up, the men cheered as one of the circling P-47s flew in low and destroyed the Panzer as it raced over a nearby hill.

A perimeter defense was established shortly after midday when the cleansing action was complete. At this point F Co withdrew to the southern edge of town close to the newly established E Co CP. Everyone was convinced that this was the final objective of the campaign, but there was still more to come. Shortly after the town was taken, Maxwell Taylor and Gerald Higgins arrived to get a situation report from Col Sink and Capt Winters. Due to the continuous radio lockdowns over the last 30 hours, Divisional HQ had been for the most part unaware as to what was happening and where. Taylor was horrified by the state of the town and asked Sink what on earth he had done. Up until then, the general had had no real idea of the terrible damage previously inflicted against Noville.

From his temporary command center in Recogne, Sink began preparations for the combined regimental attack on Rachamps before relocating the following day to Vaux. With all radio channels now reopened, full command and control was restored. The simultaneous move northeast to capture Rachamps, Wicourt, and Neuf-Moulin was supported by two companies of tanks from the 705th and 811th TD battalions.

The main attack to push the enemy forces away to the east began on January 16 at 0930hrs, after 3rd Bn had advanced along the road from Fagnoux to Wicourt (supported by 3/501), while 1st and 2nd battalions put in their assault on Rachamps from Cobru and Noville. North of Noville, Rachamps was situated in a gently sloping valley. 2nd Bn pushed forward along the N30 from Noville. After occupying the high ground north of the town, 2/506 made their advance on Rachamps, which fell on January 16. That same day, after 2nd Bn reclaimed Rachamps, First and Third armies were able to link up further north at Houffalize, spelling the beginning of the end of the German action in the Ardennes.

Meanwhile 1st Bn had moved onto the left flank of 3/506 to launch its own assault back toward Noville. 3rd Bn advanced further west and then drove north beyond Noville toward Wicourt. With 11th Armored supporting the drive, 1/506 sent spearheads across the N30 north of Noville and above Rachamps. This action cut off the remaining enemy forces, which subsequently began to surrender in ever increasing numbers.

It was late in the afternoon by the time 3rd Bn reached the high ground at Neuf-Moulin (2 miles northeast of Wicourt), as Alex Andros recalls: “The Germans had only just withdrawn and left most of their wounded behind for us to deal with.” The mass of churned up mud surrounding the recently vacated artillery positions led the men to conclude that horses had been used to move the guns. Andros continues his account:

The abandoned dugouts were deep and well constructed, with plenty of headroom, so we selected one for our CP. Leaving Capt Walker, Willie Miller, Ralph Bennett, and a few other guys in the new position, I walked over to the edge of the wood to survey the valley through my binoculars.

From where I was standing about 4 or 5 yards inside the tree line, I had a commanding view to the east, about half a mile across a shallow valley to the woods on the other side, where I could see what looked like tanks in the trees. Suddenly there was a blinding flash from the edge of the woods opposite and then everything went black. I awoke to find my helmet lying beside me with the fluorescent green identification flag that I kept inside the liner protruding through a ragged exit hole. Disorientated and bleeding – despite suffering from concussion – I realized that a shell fragment had ripped through the upper part of my helmet, narrowly missing my skull. I yelled for a medic but nobody came, so as it was getting dark, I crawled back to the CP where Willie Miller administered first aid and arranged for me to be evacuated.

After Andros had gone, Miller assumed command of 3 Ptn. Later that night, during a battalion commanders’ meeting, Col Patch got up and told the handful of officers who were left that he was planning a possible attack the following morning. At that time, apart from Capt Walker, Willie Miller was the only officer left from H Co and he was not impressed by the order. When excited or agitated, Willie’s voice went up several octaves as he squawked, “Hell, sir, I’ve only got 11 men at my disposal – what on god’s earth are you expecting me to do with them?”

Jimmy Martin had been ignoring the symptoms of emersion foot for the last ten days because he did not want to leave his post or let anyone down. “Eventually my feet turned black, and on January 15, I asked Capt Doughty for permission to leave the front line and gingerly walked about half a mile to the nearest aid post. I later learned that another few days in theater and I would have lost my toes.” Despite the dreadful losses suffered by H and I companies, G Co still had 56 men available for duty. However, over the next seven days the company would lose a further 30 percent of its remaining strength (including Capt Doughty) to trench foot and other non-battle-related injuries. Jim Martin was evacuated to the United Kingdom by Norwegian hospital ship and spent several weeks in Cirencester, where an entire hospital wing was dedicated to emersion and cold injuries. “For many like me, the condition was so painful and sensitive that we were made to lie in bed with our lower limbs exposed. Any draft or movement, such as a nurse walking by, caused an intense burning sensation to the feet … which was pretty grim at times.”

Where dead men sleep

Finally, the regiment handed over control to the newly formed 17th Airborne Division, and 3rd Bn spent their first stress-free night under cover in a warm barn at Luzery. “When my jump boots came off for the first time since December 17, I found that my socks had completely disintegrated below the tops of my boots,” recalls Hank DiCarlo. “The dry hay in the barn felt softer and sweeter than any luxury mattress.”

By January 18, the regiment was in corps reserve at La Petite Rosière, 6 miles south of Sibret. Frank Kneller remembers being taken by truck to a frozen lake, where water was being pumped to a row of showers. “We took one look at the facility and refused to get off the vehicles. After many protests, eventually we were taken to a nearby town where we were allowed to wash and bathe in a proper bath house with hot water – the ultimate luxury.” It was here that Kneller was evacuated with advanced trench foot and was lucky not to have both feet amputated.

During this time around 500 men from the 101st were selected to attend a Silver Star ceremony at the main square (which had recently been cleared of debris) in Bastogne, hosted by Troy Middleton, Maxwell Taylor, Gerald Higgins, and BrigGen Charles Kilburn from the 11th Armored Division. Also in attendance was Mayor Leon Jacqmin, who, after delivering a short but emotional speech, presented Taylor with a flag representing the official colors of the city. Frank Marchesse and Alden Todd from F/502 were part of the small group chosen to represent their regiment still fighting at Bourcy. As the two men were walking through Foy, Todd stopped at the Chapelle Ste-Barbe and retrieved a small handbell from the ruins as a souvenir. Some 50 years later Alden returned the bell, which now sits in its rightful place on the altar.

In total five soldiers were honored on the 18th, including the commanding officer of 1/502, Maj John D. Hanlon, Lt Frank R. Stanfield, S/Sgt Lawrence F. Casper, and Pvt Wolfe. Before reviewing the troops, Middleton, Taylor, and assembled staff officers posed for the press beneath a sign on the wall of a nearby building. The sign, posted close to the main road junction, aptly summed up the siege experience: “This is Bastogne, Bastion of the Battered Bastards of the 101st Airborne Division.”

After a couple days’ pampering, the men were informed that they were moving to a defensive area in Alsace Lorraine. “Everyone thought we had just got out of one so-called ‘defensive’ position,” recalls Hank DiCarlo. “It was rumored that we were going to outpost a relatively inactive part of the line, but hadn’t they told us the same thing before Bastogne?”

Continuing bad weather hampered the First and Third armies’ advance, but by January 28, the enemy were pushed back to their original point of departure and the thrust into the Ardennes was declared officially over. During the coming weeks and months American and French forces attacked into Luxembourg and Germany, but the war was by no means finished for Hitler and his fanatical commanders.

Capt Fred Anderson reflects: “I Co went into Bastogne with 150 men and came out with 28. G and H companies fared little better.” Bob Webb adds: “After the final attack on Foy, Col Sink lost one of the best battalions he ever had and he knew it.” During the four weeks on the line at Bastogne the 506th PIR suffered over 40 percent casualties (although the 501st suffered the highest): 119 men were killed, 670 wounded, and 59 missing in action – total 848. The division as a whole lost 525 KIA, 2,653 WIA, and 527 missing or captured – total 3,705. Combat Command B lost 73 KIA, 279 WIA, and 116 missing or captured – total 468.

The Battle of the Bulge was arguably one of the most important events of World War II and signified the beginning of the end for Germany. The Wehrmacht had suffered some 110,000 casualties, while the total American losses had risen to 80,000, of whom approximately 19,000 had been killed. It was said that no other battle had caused so much American blood to be spilt.

Addressing the House of Commons in London, Sir Winston Churchill was quoted as saying, “This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever famous victory.”

The devastation to the civilian population was also immense, with around 2,500 people killed, and towns and villages such as Foy, Recogne, Noville, Wardin, Sibret, Chenogne, and Villers-la-Bobbe-Eau all but destroyed. Along with the massacres of US forces at places such as Malmedy and Wereth, 164 civilians were also murdered at Stavelot and Bande. So ended Operation Watch on the Rhine and the now legendary Battle of the Bulge.