Shortly after Samuel and George had taken their final departure from New York, a singular circumstance occurred. The family had been induced to leave the house in the city and retire to Greenwich, on account of the yellow fever, where they remained until late in the fall. Before moving back to town, two maids were sent to get the house ready for their reception. While the two girls were at work in a front chamber, a seabird flew in at an open window, and continued his course until he reached the partition at the back part of the room. When he wheeled, flew back to the window and went off, leaving two distinct streaks of blood on the ceiling, extending the whole length of the room. When our hero’s father mentioned the fact to a visitor, the latter replied, “If thou wert inclined to superstition, thou would be likely to imagine that was some omen relating to thy two sons who are about going to sea in the ship Globe.”

—WILLIAM COMSTOCK, The Terrible Whaleman

The 293-ton Globe was a “lucky” ship, the term was currency for a whaleship that came back full of oil from a relatively short cruise without adverse incidents. It was built in 1815. On its first voyage, which lasted a bit over two years and two months, it set a record as the first whaleship to return more than two thousand barrels of oil. Its second voyage, in 1818, when it discovered the whale-rich “Off-Shore Ground” west of northern Peru, and its third, in 1820, were just as successful. On all three of these voyages the captain was George Washington Gardner, a respected whaleman who could doubtless have retained command of the Globe for its fourth voyage but was offered a new and larger ship, the Maria, which was under construction and nearly finished in shipyards at Higganum on the Connecticut River. In the middle of July 1822, a couple of months after returning from the Globe’s third voyage, Captain Gardner loaded the ship with gear that would be needed on the Maria and turned it for the moment into a transport for a week’s trip to Higganum. The Globe had begun to look somewhat “rough,” as one of its seamen noted. With no main topmast up, it even looked like a ship in distress as it moved along the Connecticut coast; a passing ship hailed it and asked if it needed assistance.

But this was July, and the next sailing would not be until December; there was enough time for refitting back in Nantucket. That work was going on when Samuel Comstock dropped in to sign on as a boatsteerer before going back to New York to organize himself for the voyage. When he returned to Nantucket, he had fourteen-year-old George in tow.

During these days before sailing, Samuel paid several visits to a Nantucket widow, Mrs. Plum, with whom he enjoyed talking. There was something about her that made her a good confidante. Last evening, he told her on one of these occasions, he had been walking up Main Street “thinking on certain subjects.” Suddenly he was so overcome by emotion that he had to sit down on the steps of a house. A woman who knew him came by and asked what was the matter. Nothing much, just a little faintness, he replied. Nonetheless she stayed with him and walked him to his boarding house. On another occasion Mrs. Plum asked Samuel about the surgical instruments he was carrying. What were they for? To have at hand in case they were needed, he replied. Would he be up to the job of cutting off a man’s leg? she asked. Yes, he answered, “or his head either.” I’ve heard young men talk before, she said. They love to be extravagant; you’re just like the rest of them.

When the time came to sail, the Globe crossed over from Nantucket to Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard to take on provisions. The Vineyard was a congenial place to sail from since it was home to about half the Globe’s company. Captain Thomas Worth, at age twenty-nine the oldest man on the ship, was a Vineyarder. He had been first mate under Captain Gardner on the Globe’s previous voyage. William Beetle, the first mate, was a Vineyarder, as were Second Mate John Lumbert (in some records Lumbard, Lambert, or Lombard), Third Mate Nathaniel Fisher, and one of the boatsteerers, Gilbert Smith. Six of the seamen were from the Vineyard: Stephen Kidder, his brother Peter Kidder, Columbus Worth (first cousin of Captain Worth), Rowland Jones, John Cleveland, and Constant Lewis.

From the manifest in Appendix A it is evident that half of the crew were teenagers, not an unusual figure on a whaler of the time but one that nonetheless became a circumstance of the mutiny. The question, why did the crew stand for the takeover of the ship, is easy to ask, and was asked, but it can only be answered existentially. The average age of all on board the ship at the time of sailing, officers included, was around twenty. No picture of the mutiny captures the reality of events unless it shows boys’ faces. Boys are ready for hardship and hazard if the hardship and hazard come with precedents and rationales, but even adult experience is not preparation enough for outlandish and irrational evil. And none of these boys, none of the original crew except Samuel Comstock himself, was going to join in the violence of the mutiny, although one, Rowland Coffin, was suspected of prior awareness of Comstock’s plans and of questionable chumminess with the mutineers after the takeover of the ship. All the actual mutineers around Comstock were later recruits to the ship.

Two of the crewmen who were going to sea for the first time, William Lay and Cyrus Hussey, would leave their names prominently on the Globe story; their book, Narrative of the Mutiny, on Board the Ship Globe, of Nantucket, which was written with the help of another hand, was to become the most popular account of the mutiny and its aftermath. Halfway through the story, Lay and Hussey have the stage all to themselves—they become the story.

During the time that the ship was being provisioned in Edgartown, Samuel had a chance to socialize with some of the Vineyarders, to all of whom he came across as convivial, witty, and likable. Captain Worth was watching him approvingly. From the start the captain, who seemed to combine an educated intelligence with a capacity for heavy-handed shipboard discipline, saw Samuel as his kind of seaman. Samuel realized this and knew how to play to it. Indeed, in the days spent waiting to sail, he played to everyone including the captain’s bride of six months, who was easily amused by Samuel’s conversation. So perfectly did he adapt his manner to the various Vineyarders that when the story of the mutiny broke on the island, part of the shock came from the naming of Samuel, the last member of the crew that any of them would have suspected of such an enormity.

The Globe sailed on December 20, 1822, weathered a severe two-day storm, passed the Cape Verde Islands by January 9, and on the seventeenth crossed the equator. Then whaling began: on the twenty-ninth, lookouts sighted whales, boats were lowered, there was a chase and a kill, the try-pots were stoked, and the Globe sailed on, seventy-five barrels richer.

Samuel’s hatred of the ship and the shipboard work was intense. He cursed his luck at not getting to join the navy ship his heart had been set on. He cursed the whale oil, which, he said, irritated his skin and gave him boils. At the same time he was one of the best hands on the ship; he jumped to commands and was intolerant of anyone who was not as lively. When he found greenhands asleep on the deck during their watches, he splashed cold water on them. This made him sufficiently hated by some of them, but he was indifferent to the hostility of his victims and he watched with calculated pleasure as his credit with the captain grew.

It was clear to everyone on board that Samuel had moved into a favored position with the captain. In a hearing before the American consul in Valparaíso, one of the crewmen, Stephen Kidder, was asked if there had been any sign of mutiny on board the ship between its departure from the United States and its second departure from Hawaii. “No,” he replied, “Constant Lewis was once put in irons for differing with Comstock the Boat Steerer and let out next day and the Captain struck the Cook another time on account of Comstock also.” Other accounts have it that the cook was punished for being drunk, but punishment for that may well have been at Comstock’s behest. Comstock was the captain’s man; “differing with Comstock” meant trouble.

The Globe passed the Falkland Islands on February 23 and on March 1, four days before it rounded Cape Horn, spoke the New Bedford whaler Lyra, Captain Reuben Joy, which had been out seventy-two days, one day longer than the Globe. No other ship was going to share the Globe’s story as the Lyra was. It was not merely that the Globe’s and the Lyra’s captains were extremely companionable—when they met some months later off the Japan Ground, they agreed to sail in company, a familiar practice in whaling that entailed hunting together and dividing the luck and the oil—but it was the third meeting of the two ships that wrote the Lyra permanently into the Globe story. Captain Joy was on board the Globe socializing with Captain Worth just hours before the mutiny erupted; the Lyra was so close to the Globe that if the mutiny had taken place during daylight hours, it might have been possible for the Lyra to get some sense of what was happening on board its partner.

The Globe cleared Cape Horn on March 5 and moved north with remarkably bad luck, coming in sight of whales only once on the way to Hawaii. The lack of sightings was remarkable and ironic, for its route was through the Off-Shore Ground (5° to 10° south and 105° to 125° west, between northern Peru and the Marquesas), which not only was one of the richest whaling grounds in the world but also in a sense was the Globe’s property. When Captain Gardner, on the Globe’s second voyage in 1818 discovered it, it was teeming with whales. Gardner gave the ground its name, and in two years word of it had circulated like a bulletin through the whaling community, bringing ships galore to the area. Thomas Worth, as first mate on the Globe’s third voyage, saw the merits of the area when the ship worked it intensely and successfully for eight months before leaving it abruptly for the Japan Ground, which had been discovered about a year after the Off-Shore Ground, and where it was equally successful. But now that Worth was the Globe’s captain, the whales were boycotting the ship.

On May 1 the Globe was off the big island of Hawaii near “Karakakoon” (Kealakekua), where, George Comstock noted, Captain Cook had been killed. Hawaii would soon be a major stop for replenishing provisions and crews, but it was only four years before the arrival of the Globe that the first American whalers had stopped there. The day was calm and the ship stood off about ten miles from shore under light sail. Late in the afternoon the masthead watch called out black fish off the lee bow. As the black fish drew nearer, they turned into canoes, which at nightfall came up to the ship with loads of potatoes, sugar cane, yams, coconuts, bananas, and fish. The Globe bought these provisions with the Pacific trader’s coin of the realm, iron hoops. The whaleship had come prepared to do business: it is hard to exaggerate the value that natives of Oceania put on iron—it was like gold. Natives possessing pieces of iron slept with it under their heads. Around 1730, one of them said to a missionary, “Our yearning for iron is as strong as your longing for heaven.”

The Globe went on to Oahu, where it was in port less than twenty-four hours before heading for Japan. It sailed for the first two days in company with the Palladium of Boston and the Pocahontas of Falmouth, both of which had been out a year more than the Globe and both of which were to return with two thousand barrels each. A tally like that would have improved morale on the Globe, and morale was beginning to need improving, first because the six hundred barrels that the Globe took on the Japan Ground were not enough for the time spent, and second because of complaints about the food.

Bad luck with whales weighs on the minds of the crew: it means a long cruise, which means a long time away from home and a long time away from pay. On the Japan Ground the Globe met five Nantucket ships, the Sea Lion, the George Porter, the Enterprise, the Paragon, and the Phoenix, all of which were doing well and were going to return with between fifteen and twenty-five hundred barrels.

The problem with the food began five days after the ship left Oahu for the Japan Ground. The amount of meat served the crew was very irregular, sometimes twice as much as they needed, sometimes half what they needed. The fault lay not with the captain, who wanted the crew to have the standard ration of three barrels of meat a month, but with the steward, who made an unequal division. Those in the crew who were inclined to grumble, however, blamed the captain, not the steward. The grumbling lasted until the ship was back in Hawaii in late 1823, and abundant provisions were taken on board. A more enduring complaint that lasted all through the voyage, however, was that regardless of the quality and quantity of the food, the crew was not given enough time to eat. That complaint peaked right before the mutiny.

While still on the Japan Ground the Globe had a gam with the 413-ton Enterprise, on the deck of which something happened that was insignificant at the time but would come to life again during the mutiny and add one more bit of viciousness to the tragedy. A party from the Globe, including Third Mate Fisher and Boatsteerer Comstock, had gone on board the Enterprise. In a playful mood, which the spirit of the occasion encouraged, Samuel approached Fisher and challenged him to a wrestling match. Fisher was the more athletic of the two and had no difficulty winning the match. Samuel was enraged and punched Fisher, who easily went after him again and laid him on the deck. “I’ll see your heart’s blood for this,” Samuel said, but Fisher paid no attention to the threat, something that enraged Samuel even more. The humiliation never abated in Samuel’s mind.

By October 1823 the Globe had abandoned the Japan Ground and returned to Oahu. From there Second Mate John Lumbert wrote a letter home; it is the only surviving document written in the course of the voyage. Its poignancy is great, for Lumbert would be dead in less than three months.

WAHOO SHIP GLOBE

[]EMBER THE 8 1823

Most [ ] and affectionate parents it with the grate ist pleasure that i have an oppertunity to inform you of my health which is good at presant and ihoap these few lines will find you health and sperits with all thay comforts of life which is all that we can wish for i hear that the barclay has gone home and if Thomas is thare [ ] [ ] to write me thomas haden has gone likewise i should wright to them boath but i exspet that thay will both begon before this get thare all tho the pay is small to beat round cape horn whare whales are wild and scatered and oil 40 cents per galon allto ouer luck small we are about aleven months out 600 barels i [think] that i have dun [m]y part it is along time sence i herd or seen enny of you which makes me ankcious to hear from you tell sephronia July that thay must write to me and all the rest of you i am in north pasifick ocean along distance from home but our ship goes well and we have [ ] that will make her [walk] Capt worth is afine man and mr. beetel is afine man and I amiswell contented as ever I was in my life pleas to give my best respects grandmother and nancy and all thay rest [ ] too and to [parneal] and all his famaly [ ] and so i must remain your dutifull son

John Lumbert

It was in Honolulu that the Globe experienced its first desertions. Six men left the ship without authorization and one, John Cleveland, was discharged. The deserters were Holden Henman, Jeremiah Ingham, Daniel Cook, Paul Jarrett, Constant Lewis, and John Ignatius Braz; the last named appeared in records as Prass or Pray, impossible names for the Azorean boy and probably corruptions of the common Portuguese name, Braz. It is notable that with the exception of Braz none of the deserters was from Nantucket. Two of the runaways were caught and put in irons, probably in the prison of the fort that stood on the water’s edge at the end of present-day Fort Street, in sight of the anchored ships. One of the two had slender enough hands to slip out of the manacles; he released the other, and both escaped.

Captain Worth needed replacements for the crew members lost, and as all captains knew, recruiting in foreign ports was a lottery. There was no way around it, though, if the ship was short of hands. The risk of getting riff-raff or worse was always greater when the pick had to be made from beachcombers and deserters from other ships, some of them supplied by harbor crimps, a Dickensianly seedy form of lowlife. There were foreign recruits, including island natives going to sea for the first time, who were not disreputable and proved to be good seamen, but the shrewdest captain could never be sure what he had signed on until the cruise was under way.

One of the Globe’s Hawaiian recruits—small world, much too small a world—was John Oliver, the same who had been the companion of Samuel Comstock in their colorful adventures in Valparaíso three years before. Comstock and Oliver renewed the bond they had formed at the “Hit or Miss,” and admitted to their close society three other Hawaiian recruits, Silas Payne, William Humphreys, and Thomas Lilliston. Oliver was from Shields, England; Payne, from Sag Harbor; Humphreys, a black man, from Philadelphia or New Jersey; and Lilliston, from Virginia. Also signed on in Honolulu were Anthony Hanson, Joseph Brown, and Joseph Thomas. Hanson is described as an Indian and is in various sources said to be from Barnstable or Falmouth. Brown, from the islands, is not even named in the main sources but is recorded merely as “the native,” or, as George Comstock calls him, a Woahoo [Oahu] Indian—Indian at the time was a common term for a Pacific islander. Neither Hanson nor Brown participated in the mutiny.

Thomas is the most curious figure among the new recruits. None of the main sources of the mutiny story—neither George nor William Comstock nor Lay and Hussey—include Thomas in their lists of the Honolulu replacements, an omission made more notable by the fact that in the wake of the crimes on board the Globe Thomas was suspected of some association with the mutineers and, in fact, was the only man prosecuted for involvement in the mutiny. He was acquitted when tried, but remains an ambiguous figure.

Did bad treatment by Captain Worth cause the desertions in Hawaii? The severity or fairness of captains in handling their men is an issue that has come up repeatedly in stories of whaleships with fractious crews and frequent desertions, and in most cases judging the captain is not easy. Was Herman Melville’s desertion from the Acushnet in 1842, which gave him the material for his first novel, the result of bad treatment by Captain Valentine Pease or was it a lark? Desertions took place on well-run ships, and seamen stayed with badly run ones. The fact that six of the Globe crew deserted all at once on arriving in port suggests that the grumblers had been talking their complaints out and building up each other’s resolve to make the break. Six months of unsatisfactory food and hardly enough time to eat it could have done the trick.

While glimpses of Captain Worth’s treatment of his men are inconclusive, he was spoken of more favorably than not by the non-mutineers and, of course, was spoken of with the highest praise back on Nantucket. It counts for something that Second Mate Lumbert characterized the captain in his letter home as “a fine man.” It also counts for something that an impartial observer like Michael Hogan, the American consul in Valparaíso who investigated the mutiny, wrote to John Quincy Adams, then secretary of state: “It does not appear that there was cause to complain of the Captain of this Ship, which is uncommon, for in Justice to truth, my experience for upwards of three years in this Port, has proved to my conviction that the Masters of Merchant Ships trading here are oftener in error than the sailors, who by severe, inconsiderate and unfeeling treatment are driven to insubordination and desertion.”

In the long view of the events on the Globe, the only uncontrived complaint against the captain seemed to be length of meals. While the food improved once the ship provisioned in Hawaii, the time allowed to eat it did not. When the men went down to meals, they would scarcely have food brought down before the second mate would appear shouting, “Where are you there, forward? Come out of that or I will be among you.” If they did not leave the food and start up to the deck immediately, the first mate or even the captain would come cursing and threatening to break their backs.

Captain Worth had some ready responses to crewmen who complained of hunger: he told them to eat iron hoops, or he took a handful of pump bolts and crammed them in the complainers’ mouths. Both of these actions may be made to seem hostile and tyrannical but also, if the whole context is grasped, may be little more than rough official horseplay, and not enough to make Worth less than “a fine man.”

Samuel Comstock, of course, was delighted with every instance of the captain’s rough usage, even if he knew it was not serious enough to complain about, for he could put a spin on it that made it serious enough; it was easy enough to stoke hostility to the captain if one were adept at firebuilding. Almost any move or command from the captain could be made useful to the mutineers’ purposes.

The problem on the ship at this point was not any of the captain’s discipline but the poisoning of morale by most of the new crewmembers taken on in Hawaii, that “rough set of cruel beings,” as George Comstock calls them, “neither fit to die or live.” They magnified every cause for resentment. They sent a campaign of hostile talk circulating throughout the forecastle, complaining about the food, even though the food had greatly improved, and about the usage of the captain in general. The feeling generated was much uglier than the mood of complaint had been when the ship was on the Japan Ground.

Leaving Hawaii around the end of December, the ship crossed the equator, searched for whales around latitude 2° south, and then moved north toward Fanning’s Island (Fanny’s Island in George’s account), one of the Line Islands, which are strung out between Hawaii and Tahiti on the eastern edge of what is today the republic of Kiribati. The fact that no whales were raised in this cruising may be partly attributable to the indifference of the new hands to any whaling at all, their only agenda being conspiratorial. Comstock tried cautiously to sound out some of the original crew for sentiments that would make them members of his band: to William Lay, when he was alone with him in the masthead, he said, “Well, William, there is bad usage in the ship—what had we better do, run away, or take the ship?” Lay answered evasively and tried to get to the second mate and tell him what he had heard, but did not fin¬d an opportunity. It became clear to Comstock that he could count on no one but Payne, Oliver, Humphreys, and Lilliston. (Joseph Thomas reported in his deposition in Valparaíso that he had heard Comstock say that his first attempt at mutiny had been before the new recruits joined the ship in Hawaii, “but the men to aid him failed.”)

Then one day, January 25, 1824, the captain, cursing and threatening, ordered the men out of the forecastle to pull on the fore brace. He singled out one of them, Joseph Thomas: if he did not come up in more haste the next time, he told the seaman, he would knock him to hell. It would be a dear blow for him if he did, Thomas replied. The captain swung at him, but Thomas, ducking the blow, ran forward until he was seized by the mate, who brought him to the captain. The captain held him by the neck and grasped the main buntline and commenced whipping him. The crew who were not aloft stood in the waist, the widest part of the ship, watching the punishment in silence except for one seaman whom George refers to as Rowland—presumably Coffin, not Jones—who asked those near him “how they could bear to see the man served that way.” The crew went off to the forecastle muttering and talking desertion. Silas Payne said that if the captain flogged anyone else, they should tell him to stop. “One of the boatsteerers,” George writes, “came and told us to revenge it that he would see us out.” One of the boatsteerers, of course, was George’s brother Samuel, who was testing the mood of the crew to see if the moment for an uprising was at hand. The crew was shocked by the flogging and the sight of Thomas’s bruised back—Thomas said that he had been struck thirteen or fourteen times—but the feeling among many of them was that this was not the time to start a quarrel with the officers.

For some of them, however, what had just happened was the last straw, not the flogging by itself but the turmoil of bad feeling among the ship’s company that surfaced as the men watched. Desertion became a live question now. Several of the crew, George Comstock among them, resolved that if they came to Fanning Island, which they were fairly near, they would desert and hide out in the woods until the ship sailed.

“I had been very well used by the capt,” George writes, “and had nothing to complain of but foreseeing that there would be some noise yet between the crew and officers I was determined to leave the ship to get clear of so much turbulence and dissention.” The talk among the men ready to desert was that they would take one of the boats during the watch headed by Samuel Comstock, that is, the second watch, from 10 P.M. to 2 A.M., for Samuel had spoken with enough threatening innuendo about the ship in general to convince them that he was a safe bet to cooperate with a desertion attempt. Fanning was a far from ideal spot to set up any encampment and not a logical place to expect rescue from, but the whole question of desertion became moot.

Thomas, the seaman who had been flogged, was on his way to supper when Samuel Comstock approached him and, as Thomas puts it, “spoke a blunt word to me about the officers.” Would he, Samuel asked him, “go down in the cabin with him tonight?” In view of the state of things on the ship that day, the words carried the most sinister suggestions. Thomas temporized and told Comstock that he had been ordered forward to supper and would tell him by and by. Although this account is confirmed by several other crew members, there may be some disingenuousness in Thomas’s using it as a defense; Peter Kidder and others were convinced that Thomas did know, once Comstock had spoken to him, what was in the works. At the very least Thomas would have known that he had heard something he was obliged to report to the officers.

The whipping of Thomas took place in the morning and made it a day like no other. On one level of the ship’s company there was a conspiracy to desert, and on another there was a conspiracy to kill. For the deserters it was a matter of the right place; for the killers, a matter of the right time.

The would-be deserters were probably not close enough to the right place for an attempt; the ship’s position that day is not recorded, but on the following day it was about 120 miles north and a few miles west of Fanning. In addition, though, the decision not to jump ship could have been affected by a premonition, or more than a premonition, of what was going to happen during the second watch, when they were planning to make their move. If Joseph Thomas, in spite of his later denials, knew that a mutiny was coming during Comstock’s watch, did anyone else know? Several of the crew accused young Rowland Coffin of later saying things that made them suspect he had known something of the mutiny plans. (He was also accused of being, after the mutiny, the chief informant to Comstock about what was going on among the crew.)

For the mutineers the time was right. The hostility on board the ship over the flogging of Thomas was too opportune to pass up. Midnight between January 25 and 26 was to be the moment.

But for the officers it was a social day. The Globe was once again sailing in company with the Lyra, and Captain Joy had been rowed over to the Globe for a gam; he was on board most of the day. The two captains confirmed their plans to sail together for a while. For that purpose they would observe their present course until the middle of the night and then tack together, the signal for doing so being a light that the Globe would show. The boat sent from the Lyra to pick up its captain arrived before he was ready to leave, and the men from the boat came on board the Globe. Samuel, who was splicing the foresheet, looked at the setting sun and said to the Lyra men, “That sight reminds me of the saying of a Roman General on the eve of a battle—‘How many that watch that sun go down, will never see it rise again!’ ”

With the departure of the boat from the Lyra, the night watch was set. The three watches were manned by the ship’s three boatcrews: that of boatsteerer Gilbert Smith had the first watch, which ended at 10 P.M.; the crew of the waist boat headed by boatsteerer Samuel Comstock had the second watch from 10 P.M. to 2 A.M.; the third boatcrew, which was assigned to stand watch from 2 A.M. to 6 A.M., was headed by Third Mate Nathaniel Fisher. George Comstock did not belong to any boatcrew, doubtless because of his age, and was one of those who kept the ship during lowerings for whales, but for purposes of standing watch he was considered part of the waist boat’s crew and therefore belonged to his brother’s watch.

The evening was warm and pleasant, and the first watch was uneventful. The ship held to its northerly course, as did the Lyra, which was still easy to see in the gathering dusk. Midway through the watch, around 8 o’clock, Captain Worth came up from the cabin and spoke with Gilbert Smith; he ordered reefs to be taken in the topsails and gave Smith the orders for the night: stay by the wind until the third watch came on duty at 2 A.M., at which time the ship should tack and set a light for the Lyra, so that it could match the tack and stay in company, as the two captains had agreed earlier in the day. Captain Worth stayed on deck for about an hour; there was no foreseeable need for him to come up again until morning, for Smith would pass the orders on at 10 o’clock to the boatsteerer in charge of the next watch, Samuel Comstock, who was responsible for passing them on to the head of the third watch, Nathaniel Fisher. When the captain went below, around nine o’clock, he found his stateroom too hot for sleeping; he did not go in but climbed into a hammock rigged outside it.

Darkness had descended on the ship by the end of the first watch at 10 o’clock. The wind was low and the seas were calm. The ship was sailing more slowly now with sails reduced. Smith passed the captain’s orders to Comstock, and the first watch crew walked to the forecastle and went below. There was moonlight, but on the ship the only spot of additional light was from the binnacle, the illuminated wooden housing of the compass, and that hardly dispelled the darkness. Comstock’s watch collected on deck, and Samuel ordered one of them, his brother George, to take over the helm. His duty, George knew, would last two hours; his relief would take over at midnight.

At some point after he had taken the helm, George heard indistinct voices coming from around the mainmast, but near as that was, he could see no one, nor could he make out what was being said. There was, however, a tense and excited tone to the voices. They did not seem to be people from his watch, for if they were just attending to the ship’s business, they would have no reason to whisper. As George strained to catch a word, he was startled to hear a very clear voice right in his ear: “Keep the ship a good full. Why do you have all the head sails shaking?” Samuel had crept up close to him without George’s seeing him and was speaking with an urgency that matched that of the voices around the mainmast. George tried to comply, but Samuel came back to him several times cursing him for having the ship up in the wind. Keep the ship “a good full,” he ordered; that is, keep the sails full of wind. There was something odd about his brother’s excitement and the hushed voices in the waist. What was happening on the ship?

Samuel’s orders about full sails were not a subtle navigational concern but a terribly practical one for the mutineers. They wanted not a sound to be heard on the ship lest it awaken the officers. If the sails were full of wind (“a good full”), they were firm in place, but if not, they would flap with enough noise to awaken those asleep. George told him that the ship was already a full point (11¼ degrees) from the wind. “Mind what I tell you,” Samuel told him and took the helm himself to turn the ship to two points off the wind. George reflected that it was his duty to obey without questioning the order, for it might have come from the captain, and he tolerated his brother’s interference, for his two-hour spell at the helm was almost over. But Samuel’s behavior was beginning to be not merely strange but disturbing.

Normally at the end of his helm, a seaman in George’s position would pick up and shake a rattle that would alert his relief, and someone from his watch would come to take over for the remaining two hours. George had hardly begun to shake the rattle when his brother ordered him to stop. “It is not my helm, and I want to be relieved,” said George. “If you make the least damned bit of noise, I will send you to hell,” Samuel replied.

George watched as Samuel lit a lamp and went down to steerage. When he thought Samuel was out of sight, George picked up the rattle again, but before he could shake it, his brother came up next to him and threatened to kill him if he made a sound. This time George did what he was told; now he wanted to shake the rattle not to be relieved of his duty but to have someone else beside him. George stayed with the helm and listened for sounds from any quarter; one he heard was made by something heavy being laid on the vice bench near the cabin gangway. It was impossible to see clearly, and George did not know what made the heavy sound. Later he learned that it was a boarding knife, a sharp-pointed, double-edged tool for cutting blubber; boarding knives were between two and four feet long and two or three inches wide.

Up to this point George is an eyewitness, but for the brief climactic events of the mutiny he relies on the sounds that reached him at the helm and, more important, on an account that he received from the leader of “these murderous treacherous deceiving and unfeeling wretches,” his brother. The details of the killings are relayed from the killer to the horrified but faithful reporter, George, and through George they have come down to all subsequent accounts. A few details come from others on the ship, but the killer’s blithe confession, which he would never think of as a confession but as a boast, is the main narrative of the most horrific moments of the mutiny. Samuel talked freely—unsparingly would be a better word—to George. Shortly after the mutiny he said to his brother, “I suppose you think I regret what I have done; but you are mistaken—I should like to do such a job every morning before breakfast.”

Samuel Comstock, Silas Payne, John Oliver, William Humphreys, and Thomas Lilliston moved so silently away from the mainmast and toward the cabin that George did not see or hear them. One member of the watch did, though: sixteen-year-old Columbus Worth, the captain’s cousin, had seen the four men go aft and had caught sight of the hatchet in Lilliston’s hand. He was so terrified at the sight that he went forward to hide, not in the forecastle but huddled into a space by the bowsprit.

Payne carried the boarding knife and Humphreys the lantern, which he apparently kept covered until they were in the cabin. At the cabin gangway Lilliston broke away from the group and ran forward, wanting nothing to do with the planned killing. He had believed, he said later, that the conspirators would never actually attack the officers and he had gone along with them just to look brave. He later acknowledged that he had had a knife and a hatchet in his hands.

In a moment there was a thud, which George heard on deck as distinctly as he had heard the boarding knife being laid on the vice bench. Comstock, who was the first of the four into the cabin, slipped past the captain’s hammock, mounted the transom—the athwartships timber at the ship’s stern—to give himself some elevation above the sleeping man, raised the axe until it touched the carline at the top of the cabin, and swung viciously. The very first stroke came near to cutting the top of Captain Worth’s head off, but Samuel followed it with a second.

Payne, who had been waiting to strike the first mate with the boarding knife as soon as the captain had been attacked, stabbed Mate Beetle on cue, but the wide-bladed knife was stopped by ribs, and Beetle woke up. “What, what, what, what, what is this?” he exclaimed. “Oh Payne; oh Comstock don’t kill me. Have I not always. . . .” Comstock interrupted him, “Yes, you have always been a damned rascal. You tell lies about me out of the ship, will you. It’s a damned good time to beg now you are too late.”

Beetle struggled desperately, grabbing Comstock by the throat, bumping into the others, and knocking down the lantern carried by Humphreys, which went out. In the darkness and confusion Comstock dropped his hatchet and called out for another one; his call was a weak gasp, for Beetle was choking him. Payne felt around and by chance put his hand on the hatchet, which he gave to Comstock, who swung hard, hitting Beetle in the head and breaking his skull. The mate fell into the pantry and lay groaning.

Oliver, according to George, was “cruising round putting in a blow when it came handy,” but it was Comstock who was doing the killing. Leaving his partners to guard the door of the stateroom behind which Second Mate Lumbert and Third Mate Fisher were listening in alarmed silence, he went on deck to relight the lantern at the binnacle. George was waiting there, now at least half aware of what had happened below. George asked his brother if he intended to hurt Gilbert Smith. Yes, he would kill him; had George seen him? George said he had not; he felt sure that his brother’s threat was serious. By now George was in tears. “What are you crying about?” Samuel asked him. “I was afraid that you all were going to hurt me,” he replied. “I will hurt you if you talk in that manner,” said his brother. George stifled his tears and fell silent, fearing for his life.

Meanwhile the noise from the cabin had awakened Boatsteerer Gilbert Smith, who came up on deck without any clothes on to see what was happening. When he made out that there was a disturbance in the cabin, he went below and dressed. He went aft and looked down the cabin gangway; all that he could make out was Samuel Comstock holding the boarding knife and standing at the door of the second and third mates’ stateroom. Waving his hands in the air, Comstock was saying, “I am the bloody man; I have the bloody hand, and I will be revenged.” This line became Comstock’s mantra, and he repeated it in the course of the massacre. It was hysterical, but it was also theatrical. Revenge? He was going to let Third Mate Fisher know that he was getting revenge for the humiliation he suffered in the wrestling match on the Enterprise, and he may have had a grievance against Beetle (if he ever got to the United States, he would be the death of Beetle, he had once told Gilbert Smith). But “revenge,” like the “bloody hand” line, is stage language, or words from the backyard childhood games on Market Street.

From where he was standing, Smith heard Lumbert repeatedly asking Comstock through the locked stateroom door, “What is the matter?” Comstock did not answer. Lumbert would give Comstock anything he had, he said, if Comstock would only let him go on deck and go into the forecastle or jump overboard. If Comstock even paid attention to what Lumbert was asking—to be allowed to jump overboard—he probably did not reason out what was behind it: Lumbert was not offering to commit suicide—he was looking for a chance to swim to the Lyra, which was about three miles away. Could he have found the Lyra if it was showing no lights, and even if it was, could he have swum that far? For Lumbert the risk was better than certain death in the cabin, but the plea was idle, for Comstock was deaf to everything his victims said to him unless he could make their words into a taunt.

Where were the captain and Mate Beetle? Smith wondered. Absurd as it would seem, the thought ran through Smith’s mind that they were sleeping through all the commotion. The noise had been enough to awaken Smith, but maybe the captain and mate were heavy sleepers. He could not see the bodies, just a few feet away from him, and he could not see the splattered blood.

He turned away from the cabin, went forward looking about the deck, and managed to find, in spite of the dark, Columbus Worth hiding by the bowsprit. Worth told him about seeing Lilliston with a hatchet and coming up to hide in the best place he could think of. Did he know what was going on? Smith asked him. No, he did not. They may kill you if they find you here, Smith said, and led Worth to the forecastle.

Cyrus Hussey, who was asleep below, recalled Smith coming to the gangway and calling out, “Who is there below?” What did he want, Hussey asked. “There is a terrible time in the cabin,” Smith replied, “they have aroused me out with the noise.” Smith went aft again and came back to the forecastle, and told the now completely awakened men that the mutineers had knives and guns and that the officers were begging for their lives.

Smith was thinking clearly, but the idea of what was happening paralyzed the men; they were imprisoned by confusion and terror. They could only wait in the dark, hot, cramped quarters and listen. Suddenly they did hear something: musket fire from aft. “I will never see my father again,” Columbus Worth burst out.

The scene that Smith had witnessed in the cabin was still being played out. After relighting the lantern Comstock had gone back into the cabin with two guns to attack the second and third mates, who were still behind their stateroom door. Second Mate Lumbert, who had been questioning and pleading with Comstock, asked him through the door if he was going to kill him. “Oh, no, I guess not,” Comstock replied in a joking manner. Estimating where the two mates were in the room, Comstock fired through the door and hit Third Mate Fisher in the mouth. Was either of them hit? Comstock asked. Fisher told him where he had been hit.

Whether Lumbert opened the stateroom door or the killers forced it open, Comstock, holding one of the guns, which had a bayonet, lunged through it at Lumbert but tripped and fell into the stateroom. Grabbed by Lumbert, Comstock was able to break free but dropped his gun in the process. Fisher picked up the gun and held the bayonet at Comstock’s heart. For a moment everything froze. It could have been the end of the mutiny, but Comstock extricated himself from the hopeless situation in a fashion that was absurd enough to fit his life and luck and no one else’s: Comstock told Fisher to put the gun down, and Fisher did, hoping that his life would be spared if he complied.

Immediately Comstock seized the gun, turned on Lumbert, and ran him through several times with the bayonet. Lumbert cried, “Oh, Comstock! I’ve got a poor old father with six little children at home!” “Damn you, so have I!” Comstock replied. Comstock was inarticulate with fury and throughout the massacre had no retorts but throwing others’ words back at them.

He told Fisher that he too must die and, in particular, die to pay for the offense that Comstock had been cherishing for months. He reminded Fisher of “the scrape he had with him in company with the Enterprise of Nantucket,” the humiliating wrestling match. That Fisher had forgotten it made Comstock seem unimportant; that was infuriating. Comstock ordered Fisher to die like a man. Fisher turned about, saying that he was ready; he died instantly when Comstock fired into the back of his head.

Lumbert, bleeding from his multiple stab wounds, begged Comstock for water. “I’ll give you water,” he said, and stabbed him again. The wounds seemed impossible to survive, but Lumbert was still clinging to life.

When another musket shot, the one that killed Fisher, was heard in the forecastle, Smith started for the deck. Don’t go up, the others told him. Hide out down here or go aloft. Smith told them, however, that he would face the mutineers boldly “and if his life was to be took he would ask for ½ an hour to exercise in religious duties.” The first person he met was William Humphreys, who was holding the lantern. What is the matter, Smith asked. You’ll know shortly, Humphreys replied.

Smith went aft and found George Comstock, who was still crying. The same question and the same answer: What is the matter? I don’t really know, said George. Smith returned to the forecastle. Soon he heard Samuel Comstock on the quarterdeck giving orders to Oliver to call the crew up to make sail; Smith was the first on deck and the others followed.

In the dark the deck was a mass of vague figures shifting about and heading toward the masts. Where is Smith? Comstock called out. Here I am, Smith replied and walked up to meet Comstock next to the mainmast. Are you for us? Comstock asked. “Yes, don’t kill me; I’ll do anything you want if you will only save my life,” Smith answered. “Damn you, I will say what you will do. Go forward and set the fore top gallant sail and flying jib.” He put his bloody arms around Smith’s neck. If Samuel Comstock had been serious when he told his brother that he would kill Smith, he had his chance now, but he had just been making fierce talk. William Comstock explains Samuel’s view of Smith in a fashion that has no logic but considerable plausibility:

The reader may be curious to know what enlisted the sympathies of the man of blood so much in favor of Smith; and I should be remiss in not informing him, as by so doing I shall develope a distinguished trait in my hero’s character. Smith was a religious young man; and with all his faults, our hero entertained a high respect for sacred things, and a superstitious awe of pious persons. He told George that if he had killed Smith, God would have avenged his death, and that while Smith was with them, the Almighty would smile on their enterprise for his sake. It is surprising that nothing could shake his faith in Orthodoxy. I once labored hard to convince him that the doctrine of endless punishment was derogatory to the character of the Almighty. “Don’t try to argue me out of a belief in hell!” cried he passionately, “I tell you there is such a place; but that is not going to frighten me. If I go there, as very likely I shall, I will kick and squall and bear it as well as I can. But you can’t persuade me that there is no such place.”

Smith, the Kidders, and Thomas set the two foresails, the flying jib, the main topsail, and the spanker. Hussey, who was ordered to loose the mizzen topgallant, went aloft, looked out over the moonlit sea, and saw a body floating alongside the ship—it was either the captain or Mate Beetle. The sight and the turmoil below made him stay aloft after the sail was set until Comstock called out, “Who is [it] that I sent aloft to loose the mizzen top gallant sail?” Hussey had to come down.

Even after the sails were set, most of the men did not know what had happened to the captain and first mate. What had happened, in fact, was that the captain had been killed instantly, but the killers’ rage against him had not abated. They ran the boarding knife through his body and drove it home with a blow from an axe; it entered below the stomach and came out the neck. They struck his head again with the axe. Mate Beetle, in spite of stab wounds and a fractured skull, was still alive. Both, however, were thrown overboard through the cabin windows. Mate Beetle died in the ocean in the dark of night.

William Lay had gone aft to see what was happening just as Comstock was ordering, “Haul them fellows up and throw them overboard,” referring to the second and third mates. Silas Payne joined in to play officer and, spotting Lay, said, “You have been a damned coward all the time, come down & haul them.” When Lay saw the two bodies lying in the stateroom, he could not move. “Here—take the candle if you are afraid of them, and I’ll haul them out,” Payne said. Payne called up to the deck for rope. One rope was tied around the neck of Fisher, who had had his brains blown out, and the other rope around the feet of Lumbert, who like Beetle had survived in spite of his massive injuries. Lumbert was dragged naked to the place where blubber is cut in the center of the ship. He had strength enough to say, “I thought you said you would spare my life.” Comstock replied, “Damn you, I’ll spare your life.” When an effort was made to throw him overboard, Lumbert grasped the plank sheer, the top plank covering the gunwale, with his hands. Comstock called for a hatchet but did not use one, instead kicking Lumbert’s fingers until he lost his grip and fell overboard. Seeing that Lumbert, despite his multiple stab wounds, swam quickly once he was in the water, Comstock called out, “Lower away the boat—he’s alive—he swims.” The cranes were swung out and the boat partway down, when Comstock countermanded the order: “Hoist her up again; he has a pretty good wound; he won’t live.” What had dawned on Comstock, and probably everyone on deck around him, mutineer and innocent, was that the likelihood of Lumbert swimming to the Lyra was virtually nil, while the likelihood of the boat, once in the water, heading for the Lyra was great. By the moonlight, Smith, standing at the mizzen, watched Lumbert swimming an amazing number of strokes, then lost sight of him. Joseph Thomas said that Lumbert swam two or three rods in the direction of the Lyra.

Comstock summoned the crew and announced that he was the new captain and that his orders would be obeyed under penalty of death. He had already ordered sails set; with the reefs ordered by Captain Worth shaken out, the ship had unusually heavy sail for moving at night. The orders seemed to reflect panic, as if there was a need to get away from something. The mutineers did indeed want to get away from the Lyra; in the mizzen rigging they set the agreed-on light to signal the Lyra to tack, but kept the Globe on a different course and quickly lost the other ship. But the panic went beyond that.

Comstock ordered all hands except the helmsman below; Smith went with the rest. The sea was calm. It was about 2 A.M. The second watch was ending; the head of the third watch was dead, and the members of that watch were not on duty but in the forecastle with the rest of the crew. The mutineers were alone on deck; they were the third watch that night.

With the light of day Monday morning, January 26, the cleanup began. It was a scene of gore and havoc. The captain’s blood covered the cabin table and deck. His brains, or Third Mate Fisher’s, were splattered across the cabin floor. Cleaning up meant carrying up to the deck whatever could be moved, washing away the blood, which ran diluted into the scuppers, and, down below, scrubbing the deck and the bulkheads. It was devastating work for the men, who were habituated to the extremely messy cleanup after the trying-out of whales and were anything but fastidious. But human blood was different.

During the day light breezes came from the east-southeast and built up until about 2 P.M. The course of the ship was roughly south by southwest, and by Tuesday, January 27, it was about two hundred miles south of the scene of the crime, having passed a few miles west of Fanning Island. Comstock, who a few years before had been denied his chance to join a navy ship, was playing navy now. The first work he ordered for the day included cleaning the muskets and guns that the ship was carrying, making cartridge boxes, and preparing in general for battle with another ship. The new officers of the ship under Captain Comstock are variously named in different accounts: Payne first mate, and Oliver and Humphreys—or vice versa—second and third mates. George Comstock is listed as the new steward in brother William’s account. Oliver was regarded by the crew as such an ignorant and contemptible figure that Samuel Comstock’s addressing him as Mister Oliver struck the men as one of the minor absurdities of the new situation.

Comstock drew up laws for the ship’s company. Seamen embarking on whalers were used to signing ship’s articles, which bound them to a code of conduct, but Comstock’s laws were no ship’s articles. He ordered the crew aft and had them sit on a spar on the quarterdeck. If there was anyone, he told them, that they would rather have as captain than him, they had a right to choose that person. That democratic rhetorical flourish was not a risky offer on Comstock’s part: he held a cutlass as he spoke and had a pistol ready beside him. But, Comstock continued, if they did want him to be the captain, they would have to conform to laws that he had drawn up; any who could not bring themselves to sign the sheet should move to the other side of the deck. Terrified that such a dissent would mean death, no one crossed the deck. The laws required that anyone who saw a sail and did not report it at once or anyone who refused to fight another ship would be shot or hanged or boiled in oil in the try-pots, where the blubber was rendered down. Shades of the once popular cartoons of the missionary in the black tub over a kindling flame surrounded by grinning stick-figure natives dancing in grass skirts, Comstock’s caricature sanction was never carried out, but everyone signed the laws and affixed his seal—black seals for the mutineers, colored ones for non-mutineers.

The laws reflected the preoccupation of the mutineers with encounters with other ships. Even the morning after the killings, before Comstock had imposed the laws, Humphreys had ordered William Lay aloft to look out for sails and announced his own special sanction: if anyone on deck reported a sail before the lookout called it out, the lookout would be shot.

It was some business of George Comstock in his new role as steward that led to the next violent act on the ship. One day—or several days, depending on the account followed—after the mutiny, George, who had occasion to go into the cabin, found Humphreys, the new purser, loading a pistol. When George asked him why, he said that he had “heard something very strange and he was going to be ready for it.” George went immediately to inform his brother, who summoned Payne to come with him to the cabin. In the cabin they found Humphreys still standing with the pistol. He had heard something, he told Comstock, that had made him fear for his life. Asked what that was, he gave answers that were unclear and, George says, “suspicious.” Finally Humphreys said that Gilbert Smith and Peter Kidder were planning to take the ship. Comstock told Humphreys that he thought he was lying because he did not come to him and report his suspicion.

Comstock called Smith and Kidder into the cabin and questioned them about Humphreys’s charges; he cited the laws that he had drawn up for conduct on the ship, which included the death penalty for anyone who did not report seditious talk, but it was easy to convince Comstock that the charges against Smith and Kidder were lies. Cyrus Hussey reported that Comstock also questioned him and Rowland Jones about what Humphreys had said. Comstock then said that he would hang Humphreys in the morning but “would go through the form of the law for sake of being right but that he would choose such judges as would condemn him.” Comstock, Payne, and Oliver shook hands on the decision to hang Humphreys.

The court, complete with jurors, was convened. Some accounts state that there were two jurors, but there is reason to accept those that say there were four. Stephen Kidder, in his deposition before Consul Hogan in Valparaíso, named Payne, Oliver, George Comstock, and Rowland Coffin. Gilbert Smith gave the same list except that he named Joseph Thomas instead of George Comstock, a significant difference. There is no figure in the whole Globe drama who has left a firsthand picture of himself as perfectly as George Comstock; anyone who reads his “Narrative” would have to go through mental contortions to imagine him concurring in a death sentence on Humphreys.

In the days following the mutiny Comstock and Payne were to divide the night watch between them, sleeping and relieving each other alternately; this was apparently out of mistrust of Oliver, but, Stephen Kidder reports, on the night after Humphreys’s arrest, Comstock, Payne, and Oliver all walked the deck. In the morning six of the men, one of them Stephen Kidder, were called into the cabin and issued muskets, then sent on deck to encircle the seated Humphreys and present their bayonets to his heart. Smith and Peter Kidder sat on a chest behind the defendant; both were called to testify, as was Humphreys, “who was asked a few questions which he answered but low and unlikely.”

Comstock made a speech to the assembled company, implicitly anticipating the verdict, but adding that if Humphreys were found not guilty, then Smith and Kidder, whom he had accused, would be hanged in his stead. There was no question, however, that the verdict had been established the night before. The jury found Humphreys guilty.

William Comstock reads the whole episode as a contrivance of his brother’s to kill Humphreys not for his behavior with the pistol but for another reason: “He was much averse to having a black man on board—he always felt a strong dislike to colored persons—and was therefore willing to lay hold of any pretence to set Humphreys aside.”

Humphreys was set aside with dispatch. Comstock ordered Payne to tie Humphreys’s hands behind his back, and a watch that Humphreys had bought of Captain Worth was taken from his pocket. A cap was put over his head, he was taken to the bow, and the cap was pulled down over his eyes. Comstock had ordered two men to rig out a studding sail boom; a block was attached to it. Comstock took a rope, slushed the end of it in grease, and tied that end around Humphreys neck. He had Humphreys sit on the rail before the forerigging and ordered all hands to take hold of the rope, and he said that if any of them flinched, he would cut off their heads.

Comstock told Humphreys that if he had anything to say, he would have to say it damned quick. Comstock had sent one of the men to fetch the ship’s fourteen-second sandglass; Humphreys would have just that long to make his final statement.

Comstock stood with the sandglass in one hand and his cutlass in the other. Humprheys began, “When I was born, I did not think I should ever come to this,” but then the sand was in the lower half of the glass, and Comstock swung his cutlass to strike the ship’s bell. The crew ran aft with the rope, and Humphreys was snatched up to the yard and died without a struggle. How long he hung is unclear, but it was at least fifteen minutes. The body was cut down and thrown overboard, but, some reports have it, there then occurred one of those mischances that seem symbolically appropriate to the mutiny. The line that was left attached to Humphreys’s body became fouled aloft, and the body, like a haunting figure in a Poe story, was being towed alongside the ship. A runner hook, a heavy tool used for hoisting in blubber, was attached to the body to sink it, and the dragging rope was cut. Humphreys descended to the watery grave he shared with his officers. Humphreys’s sea chest, when opened, was found to contain sixteen dollars in specie that he had purloined from the captain’s trunk. It was all over by 9 A.M.

Humphreys’s defense, that he had heard Smith and Peter C. Kidder plotting to take over the ship, was one of the weakest he could have presented. It seemed thought up, none too quickly, on the spur of the moment; it was hesitatingly and stumblingly presented; and it accused two of the most unlikely and peaceable members of the crew of planning a mutiny within the mutiny. Smith was, after all, accommodating to the new command, and Kidder, George notes, was “a man very easily scared.” Comstock could hardly have failed to find them innocent of Humphreys’s charges after a brief examination. If anyone was plotting to retake the ship, it was not those two. But, much as it would have astonished Comstock and the other mutineers, Humphreys was probably right. Peter Kidder’s interrogation by Consul Hogan in Valparaíso ran as follows:

| Q. | Was the plan of retaking the ship conceived on board & when— |

| A. | It was determined on before the ship reached the Isld |

| Q. | Who was the principal person that projected recapturing the ship— |

| A. | Mr. Gilbert Smith— |

Hogan is not known to have raised these questions with anyone else among the escapees, something that suggests he had already learned that Kidder was one of the planners and that Smith was the chief planner.

One of the commands from the new captain was strikingly wanton and at first glance surprising, even in this theater of surprises. After the hanging of Humphreys, Comstock ordered the crew to throw overboard many of the ship’s supplies and even the valuable casks of oil still on deck. Empty casks were thrown overboard or burned; fluke ropes and rigging were flung into the sea. The act, which would outrage any whaleman or shipowner, probably owed something to Comstock’s plan to turn the Globe into something as close as possible to a warship, but it may also have been intended precisely as outrageous and contemptuous: the mutineers were discarding their identities as whalemen. Not only was the ship not to pursue whales again, but also the very signs of the work that Comstock hated so much were to be destroyed. It was retaliation on the chief mutineer’s part against every abuse that whaling had made him suffer since he served on the George six years before. The fact that the oil meant money was not an issue, for the new master of the Globe was committed to something that would take them away from commerce in oil forever. In fact, the destruction of the casks was somewhat symbolic, for the officers contented themselves with getting rid of only those still on deck; there was apparently no effort made to bring up oil from below—and the Globe still had 372 barrels on board when it finally returned home.

Another order from the new captain was to paint the ship black wherever the name Globe appeared. That meant on the stern and wherever it was branded on the spars, oars, and buckets. William Comstock characteristically exploited that black repainting of the ship in his 1838 novel, A Voyage to the Pacific, where the Globe, renamed the Ark of Blood, makes a brief melodramatic appearance, commanded by a captain “like Lucifer, fallen from Glory, and bound to Hell!”

With Comstockian grotesquerie Samuel ordered a memorial service for the repose of the souls of the murdered officers. Gilbert Smith was ordained chaplain for the occasion and delivered the scripture passage and the hymns.

Captain Comstock introduced a distinct novelty in the ship’s orders: the crew were to eat with the officers in the cabin. Whether this was more to let the crew hear what he had to say or to let him hear what they were saying, some of the things that the crew overheard were not exactly designed to improve morale. Every morning Payne and Oliver complained of nightmares in which the murdered officers appeared to them; Comstock told them that the captain had appeared in his dreams too, pointing to his bloody head. “I told him to go away,” Comstock said, “and if he ever appeared again, I would kill him a second time!”

It was doubtless not at one of these meals in the cabin but during some chance proximity to Comstock that Anthony Hanson overheard Comstock, possibly talking to himself, make a threat that everyone on the ship would have taken seriously: “. . . before we got to the Islds I heard Saml Comstock say he would send some of them adrift in the boat.” This was never done; it would not be too far-fetched to say the reason was that Comstock could not afford to waste a boat.

The course of the ship lay with the prevailing winds for the next two weeks, except for one day: “The mutineers felt ugly and malicious as we had a headwind,” George Comstock noted on February 11. The ship sailed south for the first day after the mutiny, then west along a course two or three degrees north of the equator, except for an unexplained little swerve around Howland Island, until it reached the Gilbert Islands and turned north. The shipboard discipline was as ugly as the mutineers’ reaction to the headwind: they were “barbarous . . . generally to those of the crew that were not of their party,” Peter Kidder reported.

On January 31 the captain was still ordering quasi-naval exercises: the crew was employed to make boarding pikes for use against any other ship. Here was a considerable irony: the Globe, which had such inexplicably poor luck with whales in the Off-Shore Ground and in the Japan Ground, was passing great numbers of sperm whales every day now that it was no longer a whaleship and was instead playing frigate. That luck, which was a mockery of the ship and no luck at all, lasted for over a week as the ship moved through the Gilberts and north to the Marshalls.

On February 7 the Globe sighted one of the Gilbert Islands (Kingsmills, as they were known at the time) bearing west by south. The ship stood in, and natives came alongside in canoes offering beads of their own manufacture, but they appeared to be hostile and the ship left them, ran along the shore, and at night stood off. George does not name the island but does record the next contact as “Marshalls Isle” (which in spite of the name is in the Gilberts, not the Marshalls).

Here occurred an encounter with natives that struck George with remarkable force. One of the ship’s boats was sent ashore at this island but did not land when the natives attempted to steal from the boat. Instead those in the boat backed off and fired a volley of shots at the natives, probably wounding some, and then the Globe’s boat pursued one of the native canoes with two men in it and fired into it. When they came up with the native boat, George writes, they

perceived one of them was wounded the poor native took up a basket manufactured by themselves from a species of flags [flax] familiar to those Islands & a number of beads which he offered to these inhuman cruel brutish Americans and held up his hands to signify there was all they had he would give us that if they would not kill him Oh, how unfeeling must be they hearts of such wretches they cannot be called anything better no name no tittle is half revengeful enough if the righteous are scarcely saved where have and will these vile inhabitants of the earth go hell itself is not bad enough no nor all the pains imaginable. The blood was seen to crimson the poor mans eyes grew dim alas he layed in the canoies bottom and we expect left this world which was as dear to him as to those who shed his blood—But after the devil gets full hold it puzzells a bright genious to get away let us leave this melancholy scene.

William Comstock, too, is moved in recounting the episode. After running through his brother’s narrative, he continues in a tone of moral outrage that is hard to match in anything else he has written:

The omnipotent Jehovah looked down from his seraph girdled throne, and saw one of his unsophisticated children slain for mere pastime, and that moment passed His decree that the instigator of the foul deed should die by the same weapon with which he had slain his brother, and that the accessories should be cut off by the people whom they had wronged. The Destroying Angel bowed sternly as he received his orders, and posted down to Earth to blind the understandings and distract the counsels of those whom he was commissioned to destroy.

Instead of dulling their sensibilities to atrocities, the killings on board the ship seemed to have made George and William more acutely sensitive. It is their own blood brother whom they are now ready to consign to hell, and the anonymous murdered native in his canoe whom they call brother.

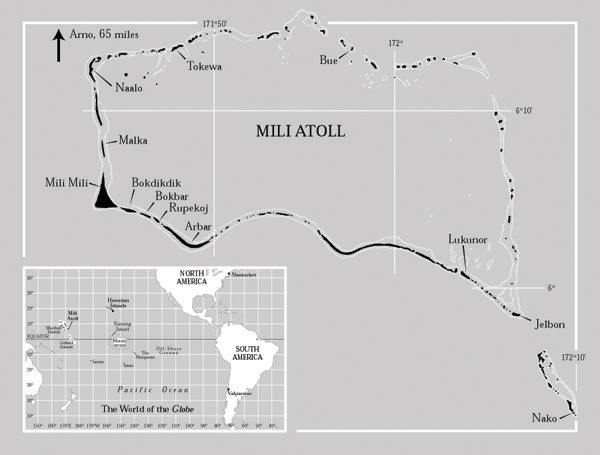

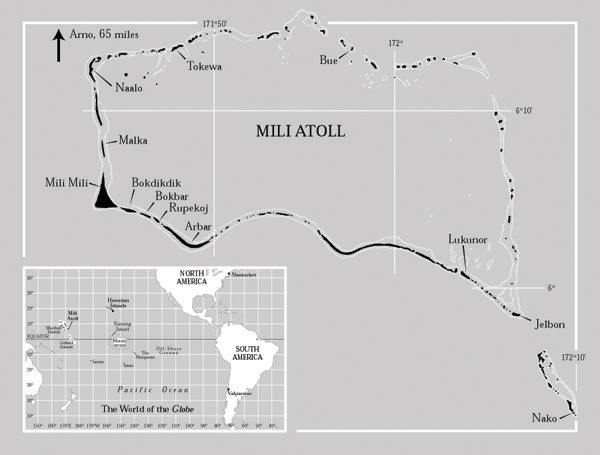

On February 10 the ship moved out of the northern reaches of the Gilberts, leaving behind what had been the announced destination of the Globe from the time of the mutiny. The Gilberts had been a shot in the dark; what would the Marshalls be? The ship headed for the southeasternmost corner of the Marshalls, the nearest one to the Gilberts, and passed Nako and Knox Islands and arrived at Mili Atoll, which on their charts appeared as the Mulgrave Islands. Judging by George Comstock’s account, the Globe passed west of the little spur formed by Knox and other islands and anchored off an island in the main string of the atoll that looked like, and proved to be, a good place for provisioning. This first landing place cannot be precisely identified but may have been Lukunor. The provisioning included, according to George, “some of the women or girls and a large quantity of cocoanuts, some fish &c.” The ship stood off during the night and in the morning, on February 12, sent the girls ashore and set out to cruise the south coast of the atoll.

George (and of course Lay and Hussey following George) recorded the stop a little too tersely to satisfy a natural curiosity about how this first encounter with the Milians went. How much communication was there? What was the mood of the natives? Did it take anything more than an invitation to get some aboard the ship? What kind of intentions were conveyed? Did the people on the ship see any canoes depart the landing site (which would have been carrying word of the strange arrivals to the high chief)? What kind of sexual generosity was involved? And why does George, the key source, mention only the girls, when Stephen Kidder says, “Comstock brought off several of the Natives, men & women, all very friendly. Kept them on board all night, gave each of the women one of the Captain’s white shirts and the men other articles of the Captain’s.”

The twelfth of February was a day of no success either in finding a good anchorage or in spotting a point ashore that seemed to have arable soil. It was not a great distance that they were covering, a little over twenty miles east and west, so that they could have doubled back more than once in the course of the day. The ship stood off overnight and continued exploring the same area in the morning; only toward evening did they resign themselves to choosing “a long narrow Island” that they had doubtless passed and observed more than once. They were fairly close to shore. The lead revealed a depth of twelve fathoms, but on being dropped again, just a little farther offshore, found no bottom. The precipitous drop-off of the coast in all the coral islands of the Marshalls is frequently commented on. The hazard of these anchorages was that getting close enough to have the anchor reach bottom put the ship in danger of being swept onto the coral by an onshore wind. But so intent was Comstock to land that a delicate midpoint was chosen and the ship anchored about 110 yards offshore in seventy-two feet of water. A kedge, a small supplementary anchor, was dropped astern to keep the ship from swinging around to the coral shore. It was getting dark now; George reports, “The sails were furled the ship moored and we all retired to rest except an anchor watch but rest as it was not fit for brutes much more for human beings we lay deploring our fate yet glad to get out.”

It was Friday the thirteenth.