5

Rebecca

The next day, three hours after telling my parents good-bye, I arrive home and turn on Sesame Street for John and Amy. My throat is clogged with a lump of tension. I want to crash into bed and hide under the covers, but my life does not give me the luxury of escapism; I must cook supper. Nothing entices me, even though I am hungry. At last I decide on spaghetti. It’s easy, and we all like it.

With robotic movements, I fill a pan with water, and place silverware with precision on our place mats, making sure each piece is straight and the same distance from the edge. I pull Amy’s high chair to the table and place jars of strained baby food in a pan of simmering water. I watch bubbles form. Steam rises and dissipates. John’s laughter at the antics of Grover drifts into the kitchen and fades away. Everything dissolves, except the lump in my throat.

By the time Jack arrives, my throat is so constricted that my ears hurt when I swallow. I force several bites of spaghetti past the lump in my throat by drinking milk. Before I replace my glass on the table, my stomach rebels. I rush to the bathroom and spew the contents of my stomach into the toilet. The vomit burns my throat, but does not dissolve the lump. I convulse with dry heaves. I gargle with mouthwash and return to the kitchen.

Jack looks up, but does not comment on my sudden departure. “What’s that?” He points to an envelope on the table.

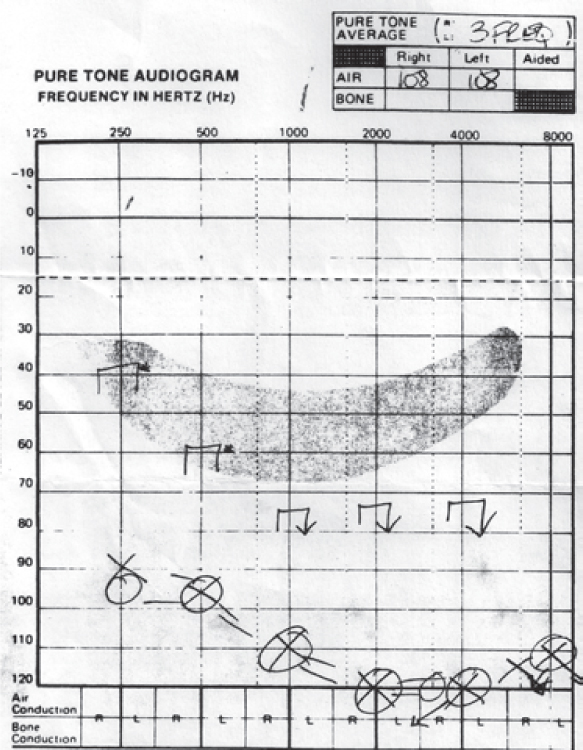

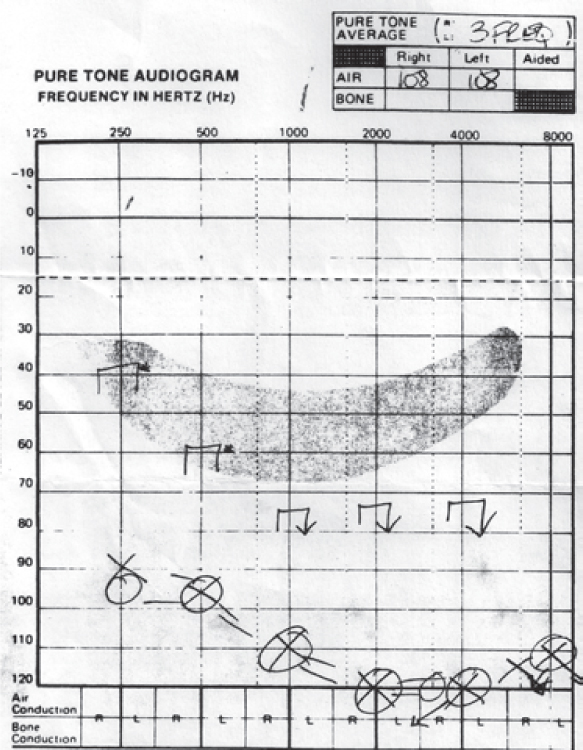

Amy’s audiogram. O and X are right and left ear measurements.

“Amy’s audiology report. I’ll show it to you after supper.” I ignore my food and feed Amy strained carrots. The smell makes my stomach spasm.

Jack pulls a sheet of paper from the envelope and studies the downward-sloping lines on the graph. Amy’s response to sound enters the graph at 95 decibels and quickly slants off the bottom of the chart at 120 decibels. He frowns. “What’s normal?”

“Normal people can detect a whisper. That’s about fifteen decibels. I’m probably talking at forty to fifty decibels now. People with normal hearing respond to sounds in that shaded area on the chart and to quieter noises above it.” Amy shakes her head at the strained turkey I offer.

“Will that hearing aid help?”

“Dr. Zimmer said we could try one, but he didn’t sound very encouraging.” I offer Amy strained peaches. She shakes her head.

“What other choices do we have?”

“If the aid doesn’t help, I don’t know what we can do.” I wipe Amy’s face with her bib and release her from the high chair.

Jack stares at the graph. If this chart portrayed a failing business, he could utilize his business degree to cut losses, increase sales, and make the business profitable, but like me, he’s in uncharted territory; nothing can make the downward-sloping line of Amy’s hearing climb.

Later that evening, after the children are in bed, Esther and J.W., Jack’s parents, surprise us with a visit. Esther snaps on the light in the children’s bedroom. John awakes and pulls his blanket over his head. Esther removes Amy from her crib and stares at her sleepy face, as if looking for a subtle difference in her appearance that would indicate she is deaf.

“How’s my little sweetie? Are you sleepy?” Amy whimpers, upset with being woken. “You hear me just fine, don’t you?” Amy pushes her hands against Esther’s freckled face, rimmed with red hair. “Okay, sleepy head, back to bed.” She puts Amy in her crib, pulls the blanket to her chin and says, “She looks fine. Are you sure this doctor is competent?”

“Let me show you Amy’s report. It’s on the kitchen table.” My offer for coffee is declined. We all sit around the table, and I explain hearing requires clarity and adequate volume. “Amy doesn’t hear any sounds until they are amplified to 95 decibels or greater. In addition, she can’t hear the higher frequencies, which include the letters f, s, th, and z, so she has problems with both volume and clarity.” I hand the report to J.W.

“Will an aid help?” he asks.

I shake my head. “Not much. Dr. Zimmer said Amy is severely to profoundly deaf. She has virtually no hearing. The best aids provide about a fifty-decibel gain, which means with an aid, Amy might hear shouting and other loud noises.”

“So we’ll all talk louder, and she’ll be just fine.” Esther pushes the report away when J.W. hands it to her.

“No amount of amplification will allow Amy to hear speech normally. A hearing aid only amplifies the sounds she hears. It can’t restore hearing. She may hear speech, but it will be garbled.” Will this day never end? I’m exhausted from driving and explaining the exam.

“Hmm,” J.W. responds.

The room is smothered in silence. Finally a mundane issue rescues us.

“The forecast for Friday is snow,” J.W. says.

“I hope the semi-truck of groceries arrives before the weather gets nasty.” Jack sighs, knowing he’ll have several backbreaking hours of work tomorrow.

Esther, a confirmed workaholic like her husband and son, usually joins their conversation, but tonight she stands and motions for me to follow her into the living room.

“You need to get another opinion.” Esther is no taller than I am, but tonight her 5-foot 3-inch frame seems large and foreboding.

“Why? Dr. Proffitt and Dr. Zimmer both say Amy doesn’t hear.”

“It wouldn’t hurt to have another doctor examine her to see if anything is really wrong.”

“I could, but what’s the point? Dr. Zimmer conducted two days of tests. I was there. I know Amy doesn’t hear.”

“He could be wrong. Did this Dr. Summer …”

“Zimmer. His name is Zimmer.” I clamp my teeth together to keep from shouting, have you heard anything I said tonight? Amy is deaf! Nothing is going to change that!

“Did Dr. Sum … uh Zimmer say what caused this?”

My body tenses, unsure where this conversation will lead. “He doesn’t think it’s a birth defect, because generally babies injured during their birth have multiple problems. Amy’s only problem is deafness. He said it’s probably genetic.”

“Genetic?” Esther scowls. “No one in our family has a hearing problem.” She pauses a moment and then blurts, “You have some cousins who are retarded, don’t you? Amy’s must have inherited this problem from your family.”

Her accusations catch me off guard. In a split second I shift from wary to red-flag-waving angry. I’m devastated by Amy’s deafness. Instead of showing a little sympathy, Esther has questioned my ability to find appropriate medical care and insinuated that my family is the cause of her deafness. I can’t believe this. “My cousins have nothing to do with Amy’s deafness. For your information, they’re distant third cousins.” My stomach gurgles with stress.

“You had the flu when you were pregnant.” Esther points her finger at me. “That’s probably what caused this.”

Why are you blaming me? I’ve already asked myself a million times if I did something to cause this! All the doctors assured me I didn’t. I feel horrible, guilty, and punished by God! What do you want from me? A confession? My knotted fists massage my stomach.

“Did you tell the doctor about having the flu?” Esther’s prominent jaw juts toward me.

My innards spasm; a trip to the bathroom will soon be necessary. “Yes, and Dr. Anderson said my bout with the flu occurred too late in my pregnancy to have caused Amy’s deafness.”

“You must have done something. Everyone in my family is normal.”

My intestines churn and cramp.

“What you should do is …”

“Excuse me.” I escape the inquisition and seek solace in the bathroom. Esther’s accusation “you must have done something,” can’t be flushed away.

When I return several minutes later, Esther and J.W. are putting on their coats. “We better go and let these kids get some sleep,” J.W. says.

Sleep? Are you kidding? I’ve just been brought up on charges, accused without warning or justification, and judged guilty! Sleep will be as fleeting as a gust of wind tonight.

Jack showers and goes to bed. After the 10 o’clock news, I slip under the covers beside him. Why does Esther think this is my fault? Why does God allow things like this happen? Please God, tell me what to do. I drift into an exhausted stupor.

My body rebels for days, refusing to accept the reality of Amy’s deafness. My throat burns, my head throbs, my ears ache. Liquids seep past the emotional lump in my throat, but food is repulsed. Aspirins lodge in my throat, gagging me. Yesterday Mother called and told me Amy’s hearing aid had arrived. How can I drive to Beatrice to get her hearing aid tomorrow? I can’t be more than ten feet from a bathroom. I decide to stop eating. Coping with hunger is less stressful than the vomiting and diarrhea. By the end of the week I add coughing to my list of complaints. Two days later I drag myself to Dr. Anderson.

Our family doctor is an older man with gray hair and a soft voice. The night he delivered Amy, Grand Island was in the midst of a howling blizzard. I smile as I remember him rushing into the delivery room wearing his blue silk bowling shirt. He has not seen Amy or me since he referred us to Dr. Proffitt. I relate the results of Amy’s hearing test at the university.

“I’m sorry. You’ll need to watch for ear infections and high temperatures; they could damage her residual hearing. If you suspect an ear infection, take her to Dr. Proffitt immediately.” I acknowledge his advice with a nod. “So, what brings you here today, young lady?”

“I feel like an outpatient from Livingston-Sonderman Funeral Home.”

He smiles. “It can’t be too bad if you can still joke about it. Hop up on the table and I’ll take look.” After peering into my ears and throat, he listens to my breathing for an extended period of time. “You have pleurisy. That’s what is causing the pain in your side. I’m prescribing antibiotics, but it will take a week or more for that pain to go away.”

What about the pain in my heart? Will that ever go away? Do you have a pill for it?

He scribbles prescriptions and hands them to me. “You take care, little mother.”

That afternoon, I reschedule my appointment with Mr. King, the hearing aid dealer to a later date. The battle of acceptance ravages my body. At night, I drift in and out of nightmares. During the day, I torment myself. Why can’t I cope? Who can I turn to? What can I do? I’ve been thrust into the role “parent of a deaf child,” but I have no mentor to tell me how to proceed.

Several days later, the intestinal rebellion is over. My stomach and I have reached an uneasy truce, but digesting the heartbreaking diagnosis of Amy’s deafness has not come without a price. I’ve lost more than 10 percent of my body weight in one week. I look svelte but feel lifeless.