6

Rebecca

The following week, John, Amy, and I travel to Beatrice where Amy receives her hearing aid on my twenty-fifth birthday. What a gift. Within a week, Amy has become accustomed to the small foreign object in her ear. She wears her hearing aid all day without complaint. Foolish me, I thought all was well, but a week later the aid is squealing unmercifully most of the day, setting my frayed nerves on edge, so I call Mr. King.

“What’s that hideous noise her aid makes most of the time?” I clamp my free hand over my ear to muffle the high-pitched squeal from the aid so I can hear his response.

“Feedback whistle,” Mr. King replies. “If the earpiece doesn’t fit tightly, sounds enter the aid through the microphone on her chest and through the opening in the earpiece, which causes that squeal. She needs a better fitting earpiece. Bring her to Beatrice as soon as you can so I can make a new ear-mold impression.”

The thought of a six-hour round-trip to Beatrice for a fifteen-minute appointment with Mr. King overwhelms me. I dislike longdistance driving, but I can’t stand listening to the piercing squeal.

When I complain to Jack that evening about another trip to Beatrice he says, “You know Bob Burns, the beer distributor?”

“No, but I’ve heard you talk about him. What does he have to do with this?”

“Bob’s a pilot.” Jack reaches for the telephone. “Several weeks ago when I told him about Amy, he asked if he could do anything to help. Maybe he’ll fly you to Beatrice.”

“That would be great.” I pray Bob would like to fly a mission of mercy.

Jack dials and after several minutes, he covers the mouthpiece and whispers, “Bob says he’ll be glad to do it.” He hands the telephone to me. “Here, you make the arrangements.”

I love to fly, so the drudgery of the grueling drive to the hearing aid dealer in Beatrice is replaced by the anticipation of soaring over the countryside. The next morning, John, Amy, and I take off into a cloudless sky in a four-seat airplane. John delights in seeing little farms and highways from the airplane window. Amy is strapped in a seat beside him. I’m the unofficial copilot. After achieving our assigned altitude, Bob allows me to hold the yoke.

At age eleven I took my first airplane ride in a small plane like this. From that day, I wanted to be a pilot. The freedom of flight, soaring into the sky, and observing the world below still beckons me. The constant vibration of the engine has lulled Amy to sleep. John is engrossed in the miniature landscape, so for a minute I clutch the yoke and live my dream of being a pilot.

We’re back home before supper. I feel like I’ve been pulled backward through a knothole. I’m exhausted and disgusted that my life is being orchestrated by a hearing aid. I don’t like the music it plays: a shrill squeal.

That night, as I tuck John and Amy into bed, the theme song for Hogan’s Heroes blares from the TV in the living room. “You know, Mother,” John says, “That’s marching music.”

I’m amazed John has such a keen ear for music. His ability to hear and understand musical rhythms makes Amy’s loss more poignant. Will she ever hear music? I remove Amy’s earpiece; the aid squeals as if wounded until I turn it off. The cord connecting the earpiece to the aid is no thicker than the lead in a pencil and just as fragile. I hold the earpiece and aid together, so the earpiece does not swing on the fragile cord, which could break the wires inside it.

I return to the living room and watch mind-numbing sitcoms so I won’t dwell on the hectic events of the day that have jarred my precise routine. At ten, when the news begins, I snap off the television. Jack won’t be home until after ten-thirty. I’m accustomed to spending evenings alone, but tonight I long for comfort and companionship. I have three sisters, and while we are close emotionally, none are geographically near me. The closest sister is one hundred miles away and she’s busy raising three young children. My other sisters live even further away. Of course I could call them or my parents, but tonight I need “in person” comforting. Having only lived in Grand Island three years, I have few close friends and none of them understand my feelings since they all have children without a disability. Jack is all I have.

A hug from him, and hearing him say, “There, there, it will be all right,” would be wonderful. But Jack and I are unable to share our pain or comfort each other. He handles his pain by working more hours at the grocery store, and I cope by spiraling deeper into perfectionism.

I align the pillows on the couch, wipe dust off the end table with my sleeve, and center the lamp on the table. Satisfied that the living room is in order, I switch off the light and wander into the children’s bedroom. I stand for a moment by Amy’s crib watching her sleep, and then I lift her and clutch her to my chest. My hug awakens her. She smiles, yawns, and closes her eyes.

I sink into the rocking chair, resting Amy’s head on my shoulder. Tears I have held inside since I heard she does not hear fill my eyes. In the dark, where no one can see, they escape, flowing in silent streams down my cheeks. A floorboard squeaks as I rock. How can Dr. Zimmer expect me to send Amy to school in Omaha? That’s too far away. I’ve read about people who never send their kids to school, I could do the same. I sniff, a futile effort to control my tears. If she went to that school, who would kiss her good-night? I cradle Amy in my arms. Her finger sucking echoes John’s thumb sucking across the room. Amy’s birthday’s in January. I’d never be with her on her birthday if she’s in Omaha. I stop the rocker. Amy’s my baby. No one is taking my baby from me! I can’t send her there; I won’t. The floorboard squawks, acknowledging my decision as I resume rocking.

I clutch Amy to my shoulder and rock. I cry for her, for me, for lost dreams, and for everything I will miss if she is away at school: birthdays, proms, first dates, goodnight kisses, tender hugs, and a special mother-daughter relationship. The tears soften but do not dislodge the lump in my throat. Unaware of my tears, Amy sleeps. In my self-absorbed grief, I don’t hear Jack enter the house.

“Rebecca, where are you?” Jack calls.

“In here. Rocking Amy.” I return Amy to her crib and wipe my face.

“What’s the matter?” He calls from the hall.

“Nothing.” I blink several times forcing my tears to recede. “How can we send Amy away to school in four years?” I walk toward his silhouette. “I can’t live without her.”

“Don’t worry about it now.” We stand in the doorway. Four inches separates our bodies; neither of us moves to close the gap. “Everything will be all right.”

Those were the exact words I wanted to hear, but they are not the least bit comforting.

Ten days later, the new earpiece arrives and the hideous squeal is gone.

Time flies, even if you’re not having a good time. A month has passed. John, Amy, and I are once again in the Temple Building on the university campus. Today, Amy will be tested wearing her aid. I’m hopeful. In the past week, Amy has turned her head if there’s been a loud unexpected noise near her.

We wait. Forty-five minutes pass. John and Amy are crabby and bored; I’m two seconds away from being short-tempered. “Stop swinging your legs, John.” I grab the leg nearest me. Amy takes advantage of my relaxed grasp to squirm off my lap and toddle across the room.

“Why?” John’s unrestrained leg moves faster.

“Because I said so, that’s why.” Amy sways by a sharp table edge. I spring from my chair.

“Amy Willman,” the receptionist says.

“Come on, John.” I swoop like a hawk on a defenseless bunny, grabbing Amy before she falls. With a backwards glance to make sure John is following me, we go downstairs.

Half an hour later, I’m seated in Dr. Zimmer’s dismal office. John stands beside me, rigid like a toy shoulder, having been warned to keep his hands at his side and not touch anything. After several minutes Dr. Zimmer strides in, jerks open a file drawer, and tugs a folder from the overstuffed drawer. I wait for him to acknowledge me. Nothing happens.

Frustrated, I blurt, “Well? What did the test show? Is the aid helping Amy?”

“There’s some improvement. Not much.” He pulls a pen from his shirt pocket and writes in the folder. “Bring her back in six months.” Without looking up he says, “You could try a Y cord.”

“What’s a Y cord?” I ask.

“Call your hearing aid dealer. He’ll know.” He stands, jams the file into the open drawer, and with one swipe of his paw-like hand slams the drawer and leaves.

My jaw tightens as does my stomach. Rebellion rises in my throat, but I squelch it. I’ve never been one to confront authority, especially male authority. “Come on, John, let’s go.”

On the drive home, I replay my short conversation with Dr. Zimmer. He said there was some improvement. That’s encouraging. I wish there was another audiologist we could see. Dr. Zimmer is an impossible monster. I envision him snatched off the planet by aliens and tortured with their shock-inducing probes. The knot in my stomach relaxes.

Over the telephone, Mr. King explains that a Y cord will allow Amy to hear sound in both ears without buying another aid. “The cord is shaped like a Y, hence its name. I don’t have any in stock; they’re not used often.”

“How much are they?” I don’t know why I ask. Regardless of the cost, we will buy it.

Mr. King quotes a price. “Y cords are a more fragile than the single cord she’s wearing now. I’ll order three, so you have a couple of spares.”

Yikes! More fragile than the one she has now? Despite my careful treatment of the aid and cord, the first cord was rendered useless after ten days. “Thanks. I’ll send a check right away.”

“Rebecca, don’t hang up. The Y cord requires two earpieces. I need to make an impression of Amy’s right ear. When can you bring her to Beatrice?”

I groan inwardly. As much as I like Mr. King and his understanding demeanor, I need a local hearing aid dealer. “Go ahead and order the Y cords for me, but maybe I’ll have the ear mold impression made here, if that’s okay. I really like you, but I can’t dri …”

“I understand,” Mr. King says. “Laverne Almquist is the Zenith dealer in Grand Island. I’ll call and tell her Amy will be coming in for an impression.”

“Thanks. I appreciate that.”

Laverne is a wisp of a woman, with a huge bouffant hairstyle. Her neck, ears, wrists, and several fingers are adorned with large jewelry. The weight of that jewelry would slow my pace, but not Laverne. She is spry and agile for a woman approaching retirement age. She’s accustomed to fitting aids on older adults and has never made an ear mold for a client as young as Amy, but she has infinite patience. Laverne took three impressions before she was satisfied. She gave John the leftover pink mold material, which kept him occupied during this ninety-minute ordeal. Laverne promises to keep the Y cords and the batteries we need stocked. She’s a breath of fresh air in my stifling life.

Amy’s first Y cord is broken after three days of use. I contemplate putting her hearing aid harness under her dress. This would protect the fragile cord, but then Amy would constantly hear the sound of fabric rubbing against the microphone. Not a good choice. The Y cord was meant for adult use, so it’s longer than needed to reach from Amy’s ears to the aid on her chest. Her hands often become entangled in the cord and when she pulls them free, at least one earpiece is jerked from her ear and dangles on the fragile cord. The resulting squeal sends me running to reinsert the earpiece before the fragile wires inside the cord break.

This morning I am cleaning our spotless duplex before a visit from my parents and my older sister, Helen, who lives in Chicago. They arrive before lunch bearing gifts. Helen gives John and Amy red, white, and blue outfits from Marshall Field’s.

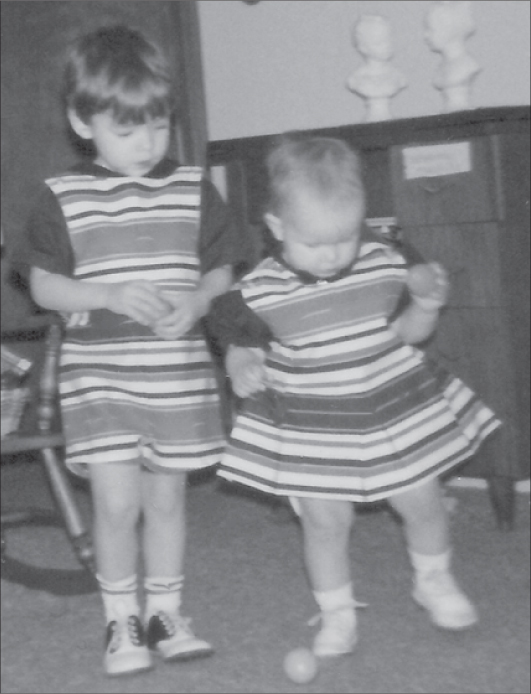

Amy and John in the matching outfits their Aunt Helen, Rebecca’s older sister, gave them.

“Thanks, Helen. They’ll look like a million dollars on the Fourth of July.” I wonder if Amy will hear the firecrackers this year. Many events in my life are measured as pre-deaf or post-deaf, filled with questions about how Amy reacted or might react now.

Mother hands me a box of Russell Stover’s candy. All dark chocolates, my favorite.

“I made something for John,” Daddy says. John and I follow Daddy outside and discover a huge wooden barn in his pickup. Daddy and I lug it into the house, and John follows carrying a toy tractor and plow. Soon Daddy and John are engrossed in farming the living room carpet.

Mother extends a book, and Amy walks to her. She lifts Amy onto her lap and together they turn the pages of Pat the Bunny. Amy touches the fuzzy bunny, but she’s more interested in John’s tractor. She wiggles off Mother’s lap. Mother’s lips smile, but her eyes are dull.

I offer coffee. Daddy declines, but Mother and Helen accept. As I pour the coffee, I pour out my heart. “I can’t send Amy to school in Omaha in four years. I’m not going to do it.”

“You have no right to deny her an education.” Helen stands. Her five-foot-nine inch frame towers over me. “How can you be so selfish? Don’t you care about Amy?”

I sink in my chair. My jaw tightens as Helen continues her harangue. My mind burns with ugly thoughts. It’s easy for you to tell me what to do; Amy’s not your child. Grandpa was right, ‘nothing like old maids and barren women to tell you how to raise your children.’ You have no idea what I’m going through. You don’t have any children. You don’t know what this is like. Three minutes into her accusing tirade, my familiar intestinal spasms start.

After my visitors leave, Helen’s piercing words gnaw at me for days. She had no right to be so mean. True, but you know she’s right. Maybe, but she could have said it in a nicer way. If she had, would you have listened? Maybe, I don’t know. I love Amy too much to part with her. As I bemoan my fate, I realize the truth of Helen’s words cannot be ignored. Helen is right; I am selfish. I don’t have any right to deny Amy the opportunity to learn, and to love knowledge as much as I do. My selfish love must be replaced with selfless love. Do I love Amy enough to do what is best for her? I don’t know. Do I really have a choice? No.

At that moment I decide Amy will receive the best education possible. I must get off my dead butt and do something constructive and quit wallowing in self-pity.

As I ponder what I can do for Amy now, my stomach is still tight with rebellion. But, for the first time in three months, I shift my focus from my feelings and contemplate what I can do for Amy.