38

Rebecca and Amy

On January 23, 1982, Amy joined millions of other kids as a teenager. We celebrate with homemade pizza and rented movies, selecting two with closed captions. Two weeks later, John is fifteen, old enough to obtain a learner’s permit, but he has no desire to drive. For weeks after his birthday, I offer to take him to the licensing bureau to obtain his learner’s permit, but he uses snow-packed streets as an excuse, which makes no sense since all that is required for the permit is a birth certificate and an eye exam.

In April, I insist he obtain his learner’s permit, which he does. I would like him to have a driver’s license so he can run errands for me. I’m planning a family vacation this summer and having him help with the driving would be great. On Friday, Amy flies home for spring break. The snow has melted. On Saturday, I will give John his first driving lesson. I remember how tense Daddy made me when he taught me to drive; I’ve vowed to remain calm.

Saturday afternoon, John is riding shotgun, and Amy is in the back seat. I drive to Fonner Park, a racetrack that has a huge parking lot and narrow abandoned streets between horse barns, a perfect place to practice driving skills. I turn off the ignition, and John and I switch positions.

“Okay, John. Start the car and drive around the parking lot.” John turns the key. The engine springs to life. He continues holding the key in the start position; the starter grinds. “That’s enough John.” I’m still calm, but Amy is not.

Being a sibling to John, I feel it’s my job to be wacky and to go batty on him. So today, while John is having his first driving lesson, I have a plan. Mother told John to check the mirrors and put on his seat belt before starting the car. When John starts the car, I lean over the seat and shout, “Go, John.”

John waves his hand at me. Wanting me to shut up and not bother him.

Mother tells me, “Sit down, Amy. Be quiet.”

I sit down, but am not quiet. John drives toward the horse barns. I shout, “Slow down. Too fast.” Then I see a stop sign and yell, “Stop!”

Mother told me, “Amy, be quiet. John is driving not you.”

Mother continued to give John instructions, like drive forward, turn left, and stop, to see how he can turn or stop properly, instead of making wide turn or quick stops. After several practices on the Fonner Park parking lot, Mother told John, “Drive home now.” The distance was not far, maybe one mile.

John drove onto a real street. As he drove toward a traffic light I say, “The light is green, John. Keep driving.”

John said something, I don’t know what, but probably “shut up.”

“Pay no attention to your sister,” Mother told John.

“You make me crazy,” John turns and signs.

“Watch the road,” Mother yells.

At the next intersection the light was red, so I yelled, “Stop, John.” John stopped fast and Mother and I were held tight by our seat belts.

All the way home I yelled orders. “Keep driving, John.” “You almost hit that car, John.” “Faster, John.” “Slow down, John.” I sure made my brother went batty and Mother, too.

Finally Mother told John to stop driving. She said to John, “Next time we’ll practice during the week when your sister isn’t home.”

Mother started the car and drove smoothly onto the busy street. I poked John in the shoulder until he turned to me. “See John. Mother knows how to do it better.”

John frowned and said, “Don’t bother me.”

Despite Amy’s backseat driving, John learned to drive and obtained his license several weeks after he turned sixteen.

Two years from now, Amy will turn fifteen. Since she has a January birthday and I do not want to teach her to drive on icy roads, I will not have her apply for a learner’s permit until she comes home for the summer. NSD teaches driver’s education, but only to students after they have obtained their driver’s license, which makes little sense to me.

Many fifteen-year-olds are thrilled to drive and some might be scared or don’t care. I was one of those with the attitude “I don’t care if I drive.” Anyway, Mother told me we are going to Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) to get my permit.

When we went into the DMV building, as usual, there was a long line of people coming to renewal their driver license, pay car taxes and apply for a learner’s permit. There were many forms available in bins along the wall. I looked for a permit license form and found it. I filled out the form and handed it to one of the examiners, along with my birth certificate. He told me, “Look in the eye exam machine and write down what letters or numbers you see.”

I looked in the machine and waited for letters or numbers to appear. I told Mother, “I see nothing.”

Mother said, “Look again.”

I told her the same thing, “I still see nothing.”

That was when the examiner walked around from behind the table to see if the eye exam machine was working or not. I thought to myself maybe the machine is broken. But the examiner told Mother, “It works just fine.”

Mother looked in the machine and said, “There are letters in there, Amy. Tell me what you see?”

I looked and finally saw a big F-O-Z with one eye and a big E with the other eye.

Mother told me the examiner said, “She needs glasses. She can’t have a permit until she can read the chart. Get her glasses and then bring her back.”

When my mother told me what the examiner said, all I could think was Oh no, am I going blind?

After my eye exam with the doctor, Mother took me to the glasses store to select frames. I was not thrilled to have something on my face. I had an idea on how not to get glasses. I would not try on any frames, and if I did, I told Mother, “I don’t like them.” And then Mother took me to another store and another again. I did the same thing.

A week later Mother offered to take me and my friend Angie Walz, who would be a senior at NSD next fall, to the mall for shopping and a movie. Angie lived on the other side of Grand Island, far from us, so I was excited to be able to spend the afternoon with a deaf friend. Mother told me, “There is an optical store at the mall. We will go there first. After you select frames, you and Angie can go to the movie.”

I still did not want any glasses at all. At the Conestoga Mall with Angie, when Mother reached her last straw, she said, “Amy, pick a frame or I will pick one for you.”

I did not look carefully at the frames, I just picked one. I choose the biggest and ugliest frame I saw. They were tan-colored plastic with big round lenses like an owl’s eyes. The side pieces bent down like the letter “C.” I thought, I don’t give a damn what they look like because I am not going to wear them at all. Mother left and Angie and I had a good time at the movie and shopping.

A week later, Mother and I returned to the mall. After the clerk fitted the glasses on me, I took them off, put them in their case, and gave them to Mother.

Mother gave them back to me and said, “Amy, you need to wear these.”

I refused to take them. I said, “Maybe later. Not now.”

Mother yelled, “Amy! Wait!”

Later, when I got to home, I still refused to wear the glasses. Mother said, “You have to wear them Amy so you can see.”

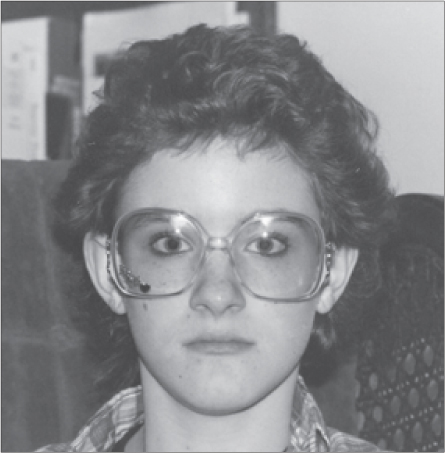

Amy with her first pair of glasses, which she disliked. Summer of 1984.

I kept saying, “No.”

“Amy, wearing glasses is not a big deal.” Mother said. “I was younger than you when I got my first pair of glasses. You’ll still be beautiful with glasses.”

“I don’t want glasses.” I started to cry.

Mother asked, “What’s wrong, Amy?”

I said, “Maybe I am going blind.”

Mother shook her head, “no,” but still I would not wear the glasses.

Having sight is very important to me and every Deaf person. We rely on our eyes to see what is happening. Without eyes, a Deaf person would find it very difficult to survive since we have already lost one sense, our hearing. But being Deaf and blind, what would I do?

A few nights later when Mother and I were playing cards, I looked at my cards and said, “Wait!” Mother looked so puzzled. I ran to my bedroom. Guess what I went there for? I picked up and put on my big, ugly glasses. Why did I do that? I could not really read the cards without the glasses. At that moment, I felt so relieved that I could read and knew I was not going blind. Of course, I got rid of my “eeew” glasses in less than a year. The next glasses I had were preppie glasses. Very classy compared to my first ugly ones.

I find it ironic that when Helen Keller was asked, “Would you rather be deaf or blind?” she chose to be blind over deaf. I thought, gosh, she must be a nitwit. I would rather be Deaf than blind. Deafness does not limit my ability to do things such as riding a bike, driving cars, and seeing nature. I depend on my eyes for everything I need to live in a hearing society. Of course, Deaf people and hearing people don’t receive equal information. Hearing people have access to radios, announcements at airports, and live news that Deaf don’t, and yet, I and other Deaf people still find a way to receive this information, just not through our ears.

I have heard stories from hearing people that they are afraid of losing their hearing. They told me, “If I lost my hearing, I would not know what to do or how to live, because I depend on my ears to tell me what is happening.”

Funny thing, I live without my ears and I am doing just fine. I understand their concern, because they have heard sounds and enjoy it. The same is true for me; I have seen the world around me and enjoy it. So, both of us, Deaf and hearing, can’t imagined losing a valuable sense once we have experienced it.

Minutes later Amy draws a card from the deck, “Going down for three.” She spreads her gin rummy cards on the table. “You lose. Too bad for you.”

I may have lost the game, but I won the battle of the glasses, which was a bigger issue. I can only imagine how scared she was, thinking she was going blind. From this point on, Amy’s glasses become part of her. They are the first thing she puts on in the morning, and the last thing she takes off at night. I should have known. When it comes to winning, Amy would utilize anything, including glasses, to sharpen her focus and have a competitive edge.

Wearing her glasses, Amy passes the eye exam and receives her learner’s permit. I brace myself for teaching another child to drive. The next evening after she comes home from her summer job, I said, “After supper you will have your first driving lesson.”

“I can do it. I know how,” she says. “Driving is easy.”

Amy said this before ever being behind the steering wheel. Her “I know everything attitude,” a strong part of her personality, may be challenged this time. “Driving is not as easy as it looks,” I reply.

John opts to stay home and play Frogger, so Amy and I depart for Fonner Park alone. Once there, we change seats. I put my hand on her arm. She turns toward me. “Amy, let’s go. Shift into gear, and drive forward, slowly.” As soon as I signed “go,” Amy turned from me and stomped on the accelerator.

The engine whined to maximum RPMs. Once again I lay my hand on her arm, this time with gripping force. She turns toward me. “Why don’t we go?”

“Because you have to shift the car into drive, first.” I point to the “D” on dash.

“Oh.” Amy’s voice reflects her I-know-that attitude.

“Put the car in drive, and go slow …” Amy turns away from me and floors the accelerator again. The tires squeal; burnt rubber fills my nostrils. Amy turns toward me, frowning. “Take your foot off the brake,” I say.

We charge forward. Amy clutches the steering wheel like a NASCAR driver. We zigzag through the lot. Yikes! Now what? If I tap her arm, she’ll look at me and may hit one of the many light poles in the parking lot. If I do nothing, she’ll shoot through the parking lot onto a busy street. “We’re all gonna die,” I murmur, a line I often say when a situation is perilous.

I wave my hand in her field of vision and sign, “stop.” I’m thankful for seatbelts. I’m yanked back by my shoulder restraint to the point of pain. Amy turns, nods her head, and smiles with confidence.

“Watch me!” I sign and say through clenched teeth. “Don’t go until I say so.” I jerk the shoulder restraint to release it.

“Fine,” Amy signs. “Now what.”

“Drive in a straight line. See the lines on the parking lot? Drive on one of them. Go slow, and stop by each section marker.” I point to large letters on the light poles.

“Okay.” Amy takes her foot from the brake and accelerates.

“Go slow!” I scream to no avail.

After Amy completes several jackrabbit starts, and bone jarring stops, she turns to me while the car is still moving. “Now what?”

“Put the car in park. I’ll drive home.”

When we arrive home, John runs up from the basement. “I won the first level of Frogger. I got all five of my frogs home safely.”

“Good,” I reply. “We got home safely too. No thanks to Amy.”

“I drove, John,” Amy says. “I told you I knew how.”

I roll my eyes up and shake my head. “She needs a few more lessons.” I say to John behind Amy’s back. I tap Amy’s shoulder. “Tomorrow after work we’ll drive again.”

Amy shakes her head. “No. I don’t need to. I know how.” She walks toward the basement door. “John, you won Frogger. Let me see.” Amy’s voice is full of disbelief.

“Wait, I’ll show you.” John grabs Amy’s shirt, but she twists away from him.

“I know how. I can do it.” She runs down the basement steps.

Each afternoon, when I return from work, I ask Amy, “Do you want to drive tonight?”

Her response is always the same, “No. I know how. I can do it.”

A year passes. The summer after her sophomore year I am determined she will learn to drive.

The next summer I was sixteen, Mother insisted I had to learn to drive. She said, “I don’t care if you ever drive after you get your license, but you need to have a license for an ID.” My learner’s permit had expired, so we went to the DMV to get a new one.

This time my brother went with me when Mother gave me a driving lesson. John was excited, because he wanted revenge from all the screaming I had done to him two years ago. I slipped on my seat belt. In the rearview mirror I saw John’s face. His eyes were filled with mischief. He was ready to drive me batty, but he couldn’t, because Mother was signing to me what to do, and at the same time I was trying to watch the road. Eventually Mother said, “Watch the road.”

John realized he could have no revenge, because he was in the back seat, and I could not turn to see his signs. He could scream “stop,” “go,” “red light and green light” all he wanted and I could not hear him, but he still wanted revenge. He knew I could feel vibrations, and that they are distracting to me, so he kicked the front seat where I was sitting.

I yelled, “Stop it, John. You bother me.”

He kicked more. I didn’t like the thump, thump, thump over and over on my seat. “Stop it,” I yelled again, but he didn’t. Good enough, he drove me batty.

Mother told John, “Quit that and be quiet.”

I looked in the rear view mirror. John had a huge grin on his face.

In general, Deaf people are sensitive to pounding or vibrations; it can be distracting. One sensation Deaf people enjoy is a loud band or concert that makes the floor or table vibrate. We can sense the noise of the music that way and feel the beats. In Deaf culture, (our Deaf World) it’s okay to pound the table or stomp the floor in a proper place (usually at home, dorm and school; not at library, church (unless it is deaf church), and restaurant) to get the attention of other Deaf people; this is proper, but making these vibrations for no reason is annoying.

So what John did to me was very distracting, similar to a hearing person tapping a table with a pencil. That action might be distracting to hearing people. My distraction to John when he was driving was to shout orders and make noise. John’s distraction to me was making vibrations. So, we both had the perfect sibling revenge.

Many months after I passed my driver’s test and had my license, I was going to run an errand while Mother was a work. We had a Monte Carlo with a dark red body and a white top. When I backed out from the garage, I scraped the driver’s side along the garage structure. A hearing person would have known what was happening, because of the scraping noise, but I did not know it until I saw what I had done.

I thought to myself, “Oh no! What should I say to Mother?”

John said, “You will be in trouble.”

I had a good idea. When Mother came home and saw the car she was not happy. She asked, “What happened?”

I said, “I backed straight out of the garage and all of a sudden the garage structure moved and bit the car. That’s how it happened.”

Mother tried not to laugh but she did. She said, “I’ve never heard of a garage biting a car.” Afterward she told me I had to buy new wood trims for the garage.