| 3.1 | 25 Commandments of Injury Prevention for the Triathlete |

Get instruction. Investing in a good coach or training camp and learning how to become a coachable athlete are the best two steps you can make toward an injury-free athletic career.

Get instruction. Investing in a good coach or training camp and learning how to become a coachable athlete are the best two steps you can make toward an injury-free athletic career.

Good coaches know how to set up an intelligent schedule that incorporates necessary recovery time and yields smart progress. It also eliminates the stress of decision-making and planning that every self-coached athlete struggles with.

Use a heart-rate monitor. Ideally, you’ll learn to use a heart-rate monitor from your coach, as most triathlon coaches rely on the information spewed by the technology to effectively guide your training. The most valuable attribute of using a monitor is to keep you from going too hard. If you used a monitor to restrain yourself from leaping out of the aerobic zone your entire triathlon career, you’d be head and shoulders above most self-coached triathletes who go too hard and too often.

Use a heart-rate monitor. Ideally, you’ll learn to use a heart-rate monitor from your coach, as most triathlon coaches rely on the information spewed by the technology to effectively guide your training. The most valuable attribute of using a monitor is to keep you from going too hard. If you used a monitor to restrain yourself from leaping out of the aerobic zone your entire triathlon career, you’d be head and shoulders above most self-coached triathletes who go too hard and too often.

Develop a foundation of strength and balance. Core strength, as it’s popularly called, not only helps reduce the risk of injury due to imbalance and lack of support, but also helps you channel more power to locomotion. Balance is important in swimming, biking and running; muscular imbalances often lead into a downward spiral of performance, or at least lock us onto a plateau. Developing core strength and balance and keeping them in check are invaluable to a long and prosperous career. They’re easy to find, too: Local fitness centers these days offer a variety of core classes: Pilates and athletic yoga. Books and videos are also easy to find. Talk with your coach about implementing a core program into your overall schedule.

Develop a foundation of strength and balance. Core strength, as it’s popularly called, not only helps reduce the risk of injury due to imbalance and lack of support, but also helps you channel more power to locomotion. Balance is important in swimming, biking and running; muscular imbalances often lead into a downward spiral of performance, or at least lock us onto a plateau. Developing core strength and balance and keeping them in check are invaluable to a long and prosperous career. They’re easy to find, too: Local fitness centers these days offer a variety of core classes: Pilates and athletic yoga. Books and videos are also easy to find. Talk with your coach about implementing a core program into your overall schedule.

Use uphill running for strength. The greatest running coach of our times, Arthur Lydiard, says the key to preventing hamstring injuries (along with other running injuries) is to develop strength using hill training or running up stairs. It makes sense: running and bounding uphill is turned into strength work by virtue of gravity and bodyweight, and it’s a much safer activity (and probably more effective) than doing heavy squats in the weight room. By adding a session or two of stair running or light hill repeats into your training week, you’ll be in business.

Use uphill running for strength. The greatest running coach of our times, Arthur Lydiard, says the key to preventing hamstring injuries (along with other running injuries) is to develop strength using hill training or running up stairs. It makes sense: running and bounding uphill is turned into strength work by virtue of gravity and bodyweight, and it’s a much safer activity (and probably more effective) than doing heavy squats in the weight room. By adding a session or two of stair running or light hill repeats into your training week, you’ll be in business.

Master technique. In laying out a program, your coach will most likely give you drills to do for all three sports. Don’t pass these up as unimportant. Drilling your technique will improve efficiency, enhance balance, improve specific flexibility and streamline the flow of power into speed.

Master technique. In laying out a program, your coach will most likely give you drills to do for all three sports. Don’t pass these up as unimportant. Drilling your technique will improve efficiency, enhance balance, improve specific flexibility and streamline the flow of power into speed.

Treat yourself to an occasional sports massage. Over the last decade, some studies looking for the value of sports massage have come up empty. But it’s almost impossible to find an elite endurance athlete these days who doesn’t count on massage for enhanced recovery, relaxation, and injury prevention. If it’s good enough for Lance Armstrong, it’s good enough for you.

Treat yourself to an occasional sports massage. Over the last decade, some studies looking for the value of sports massage have come up empty. But it’s almost impossible to find an elite endurance athlete these days who doesn’t count on massage for enhanced recovery, relaxation, and injury prevention. If it’s good enough for Lance Armstrong, it’s good enough for you.

Don’t overuse the track. Track workouts are addictive because they give you specific feedback as to your fitness, and when you start getting stronger, stopwatch times plummet and you want to use the track more. But tracks are generally hard-surfaced and are always circular, both attributes that invoke injury danger, particularly when you’re running fast. You can do speed and tempo workouts on the trail or on the road, and often to greater benefit. And most certainly lower the chance of getting hurt.

Don’t overuse the track. Track workouts are addictive because they give you specific feedback as to your fitness, and when you start getting stronger, stopwatch times plummet and you want to use the track more. But tracks are generally hard-surfaced and are always circular, both attributes that invoke injury danger, particularly when you’re running fast. You can do speed and tempo workouts on the trail or on the road, and often to greater benefit. And most certainly lower the chance of getting hurt.

Don’t run in broken-down shoes. While the outsole on a pair of training shoes may not appear even remotely diminished (most are made of very tough carbon rubber), the true heart of a shoe is the midsole, which wears down much faster. Running shoes certainly aren’t cheap, but if you can find a way to rotate in a fresh pair every three months (or sooner), you’ll reduce the chance of certain types of injury.

Don’t run in broken-down shoes. While the outsole on a pair of training shoes may not appear even remotely diminished (most are made of very tough carbon rubber), the true heart of a shoe is the midsole, which wears down much faster. Running shoes certainly aren’t cheap, but if you can find a way to rotate in a fresh pair every three months (or sooner), you’ll reduce the chance of certain types of injury.

Don’t raise your running volume too quickly. Bump your running mileage up too quick, and you can count on it bumping back. While your cardiovascular system responds rapidly to running, it takes the muscles, bones, tendons and ligaments some time to catch up. If you’re new to running and triathlon, if you can make it through the first year by being patient in respect to volume increases (like increasing no more than 5-10% every three weeks), you’ll have a solid, consistent year of base work under your belt. Getting injured because of impatience and being overly excited will waste most of it, and you’ll be starting off right where you were at the beginning.

Don’t raise your running volume too quickly. Bump your running mileage up too quick, and you can count on it bumping back. While your cardiovascular system responds rapidly to running, it takes the muscles, bones, tendons and ligaments some time to catch up. If you’re new to running and triathlon, if you can make it through the first year by being patient in respect to volume increases (like increasing no more than 5-10% every three weeks), you’ll have a solid, consistent year of base work under your belt. Getting injured because of impatience and being overly excited will waste most of it, and you’ll be starting off right where you were at the beginning.

Incorporate mandatory rest days. Taking one day off from training a week is a smart way to allow your body to recover, and also teaches your mind and body how to deal with a day without exercise. If you work a traditional Monday through Friday job and do a lot of training on the weekend, Mondays make a good pick for this technique.

Incorporate mandatory rest days. Taking one day off from training a week is a smart way to allow your body to recover, and also teaches your mind and body how to deal with a day without exercise. If you work a traditional Monday through Friday job and do a lot of training on the weekend, Mondays make a good pick for this technique.

Don’t sacrifice sleep. Only the occasional genetic freak can get away with training 20 hours a week or so for an Ironman while getting away with six or so hours of sleep. Most of us are going to need the full eight hours to fully recover (plenty of elite endurance athletes prefer 10-12 hours of sleep).

Don’t sacrifice sleep. Only the occasional genetic freak can get away with training 20 hours a week or so for an Ironman while getting away with six or so hours of sleep. Most of us are going to need the full eight hours to fully recover (plenty of elite endurance athletes prefer 10-12 hours of sleep).

The key to remember is that progress is not made while you train; rather it’s made while you recover. Skipping on sleep to get everything in is wasting your training time and effort, and the fun of it is going to evade you in a serious way.

Get your bike set up by an expert. One of the best reasons to go to a good triathlon camp or to get a good triathlon coach is that one of the first things they do is check your bike set up.

Get your bike set up by an expert. One of the best reasons to go to a good triathlon camp or to get a good triathlon coach is that one of the first things they do is check your bike set up.

Except for crashes, almost all cycling injuries can be traced to how a bike fits you, your position on the bike, and the type and setup of shoes and pedals. In addition to making sure your bike is set up, you can help it out by implementing core body strength training into your overall schedule.

Take glucosamine and chondroitin supplements for the knees. The medical community is generally skeptical of these supplements that have been claimed by some to reduce knee pain and even repair cartilage. But as of right now, the scale seems tipped in support of glucosamine and chondroitin supplementation, and they appear to be safe to take. So if you’re nearing or over the 40-year-old mark and have knee issues knocking on your door, this is a worthwhile investment. And of course, talk to your doctor about it.

Take glucosamine and chondroitin supplements for the knees. The medical community is generally skeptical of these supplements that have been claimed by some to reduce knee pain and even repair cartilage. But as of right now, the scale seems tipped in support of glucosamine and chondroitin supplementation, and they appear to be safe to take. So if you’re nearing or over the 40-year-old mark and have knee issues knocking on your door, this is a worthwhile investment. And of course, talk to your doctor about it.

Overwhelm early-warning injury signs with care. Most injuries flash warning signs to let you know things are coming apart. Your job is to listen and act. San Francisco football great, Brent Jones, had a long career in the NFL because he attacked injuries with a fury, treating injuries diligently with ice, therapy and following any advice given to him by trainers as if it was divine guidance.

Overwhelm early-warning injury signs with care. Most injuries flash warning signs to let you know things are coming apart. Your job is to listen and act. San Francisco football great, Brent Jones, had a long career in the NFL because he attacked injuries with a fury, treating injuries diligently with ice, therapy and following any advice given to him by trainers as if it was divine guidance.

For example, let’s say you finish a long run and in the last few miles you felt a tenderness arising within the Achilles tendon on your left foot.

Don’t just dismiss it as something that will go away. Take immediate action with ice, elevation and evaluating what the cause of the problem is.

Treat your injury with ice, compression, elevation and rest. But whatever you do, don’t stretch it! When a tendon or muscle is pulsing with injury pain, resist the temptation to “stretch it out.” At this point in time with an injury warning sign, the tissue is looking for a break from the action. Stretching is exactly the opposite you want to do at this time. It will just exacerbate the problem. Wait until the pain has gone away in a day or two (or more), and then gently re-introduce light stretching to the area.

Treat your injury with ice, compression, elevation and rest. But whatever you do, don’t stretch it! When a tendon or muscle is pulsing with injury pain, resist the temptation to “stretch it out.” At this point in time with an injury warning sign, the tissue is looking for a break from the action. Stretching is exactly the opposite you want to do at this time. It will just exacerbate the problem. Wait until the pain has gone away in a day or two (or more), and then gently re-introduce light stretching to the area.

Obey the request of a warning sign by taking a day off or switching to aerobic cross-training. If a running injury has struck, along with aggressive first-aid, consider leaving the running shoes in the closet and spend a few days on your bike or in the swimming pool. The non-impact nature of swimming and biking will keep you fit and enhance dodging the injury with active recovery. During the cross-training days, continue to ice the site of the injury before and after your training.

Obey the request of a warning sign by taking a day off or switching to aerobic cross-training. If a running injury has struck, along with aggressive first-aid, consider leaving the running shoes in the closet and spend a few days on your bike or in the swimming pool. The non-impact nature of swimming and biking will keep you fit and enhance dodging the injury with active recovery. During the cross-training days, continue to ice the site of the injury before and after your training.

Talk to an expert. Many elite athletes have become elite because, in addition to addressing injury warning signs with first-aid and care, they immediately seek appropriate medical advice upon the flare up. Along with advanced treatment, a sports injury professional will help you map your way away from injury danger by recommending other forms of therapy like massage, and give you a set of specific instructions. Consult with the sports medicine world. Is there a leg length discrepancy? Are you making a technique mistake? Are you overtraining? Are your shoes right? By being aggressive in the beginning, you can dig injuries up by the root and kill them before they take hold.

Talk to an expert. Many elite athletes have become elite because, in addition to addressing injury warning signs with first-aid and care, they immediately seek appropriate medical advice upon the flare up. Along with advanced treatment, a sports injury professional will help you map your way away from injury danger by recommending other forms of therapy like massage, and give you a set of specific instructions. Consult with the sports medicine world. Is there a leg length discrepancy? Are you making a technique mistake? Are you overtraining? Are your shoes right? By being aggressive in the beginning, you can dig injuries up by the root and kill them before they take hold.

Tell the medical expert you can only handle so much. If a physical therapist or sports medicine expert writes up a therapy program that looks like it’s going to take two hours a day, ask them if they can’t pare it down a bit. Assuming you can still cross-train through an injury problem, if the program takes more than 30 minutes, there’s a good chance you won’t have the time or motivation to do it all. Sometimes less is more.

Tell the medical expert you can only handle so much. If a physical therapist or sports medicine expert writes up a therapy program that looks like it’s going to take two hours a day, ask them if they can’t pare it down a bit. Assuming you can still cross-train through an injury problem, if the program takes more than 30 minutes, there’s a good chance you won’t have the time or motivation to do it all. Sometimes less is more.

Decrease impact stress when healing. We’ve already mentioned this, but it’s worth mentioning again. While you’re on the mend, and even when you’re just being careful after getting an injury warning sign, take your running to a field of soft grass or trail. Stay off the pavement. Even better, buy a water-belt and do your run workouts in the pool. They’re pretty boring, but the hydrotherapy action of the water will aid your therapy.

Decrease impact stress when healing. We’ve already mentioned this, but it’s worth mentioning again. While you’re on the mend, and even when you’re just being careful after getting an injury warning sign, take your running to a field of soft grass or trail. Stay off the pavement. Even better, buy a water-belt and do your run workouts in the pool. They’re pretty boring, but the hydrotherapy action of the water will aid your therapy.

Use the Styrofoam cup trick. This is a classic tool of many marathoners and ultrarunners: Take a Styrofoam coffee cup, fill it with water, and stick it in the freezer. After a workout, if you feel a bit of pain or tenderness on the knee or around the foot, take out your cup of ice, tear off the bottom, and rub it on the pain. By having a cup like this handy, it will increase the chances that you’ll use it.

Use the Styrofoam cup trick. This is a classic tool of many marathoners and ultrarunners: Take a Styrofoam coffee cup, fill it with water, and stick it in the freezer. After a workout, if you feel a bit of pain or tenderness on the knee or around the foot, take out your cup of ice, tear off the bottom, and rub it on the pain. By having a cup like this handy, it will increase the chances that you’ll use it.

Take time off at the end of the season. Training year in and year out will take its toll. Try and plan to take a month every year and have some fun with it, allowing your body to recover from the grind of running and triathlon. Play ping-pong, go hiking, or take up something different like rowing or aerobics. The mental break will be just as good for you as the physical break.

Take time off at the end of the season. Training year in and year out will take its toll. Try and plan to take a month every year and have some fun with it, allowing your body to recover from the grind of running and triathlon. Play ping-pong, go hiking, or take up something different like rowing or aerobics. The mental break will be just as good for you as the physical break.

Recalibrate your head for a comeback. If you’ve been away from the sport for a matter of months or years, then be sure to forget about how fast you were and train at the slower pace you need to. It might be frustrating and humiliating, but a comeback usually takes just as much time as it took to get to that amazing peak you used to be at. It’s a humbling experience, but you have to let go or face punishment from the inevitable injury that awaits the impatient.

Recalibrate your head for a comeback. If you’ve been away from the sport for a matter of months or years, then be sure to forget about how fast you were and train at the slower pace you need to. It might be frustrating and humiliating, but a comeback usually takes just as much time as it took to get to that amazing peak you used to be at. It’s a humbling experience, but you have to let go or face punishment from the inevitable injury that awaits the impatient.

Cross-train your way down from being overweight. Heaviness and running don’t mix well. The impact stress delivered to the joints can be too much for a body struggling to adapt. Using triathlon to reduce your weight, get fit, and adapt to running gradually is one of the great benefits of multisport over pure running.

Cross-train your way down from being overweight. Heaviness and running don’t mix well. The impact stress delivered to the joints can be too much for a body struggling to adapt. Using triathlon to reduce your weight, get fit, and adapt to running gradually is one of the great benefits of multisport over pure running.

Remember that salt is your friend. As a triathlete, you’ll undoubtedly train or race in hot conditions. Heat injury is one of the most dangerous injuries you’ll ever come close to. One of the reasons triathletes do get tripped by heat injury, particularly hyponatremia (when levels of sodium become dangerously low), is because they stick solely to water for fluid replenishment. Sports drinks, like Gatorade, have an appropriate amount of sodium within their mix, and not only replenish your sodium stores but help the body absorb water. In Ironman competitions, pretzels, soup, and other salty products may do well for you.

Remember that salt is your friend. As a triathlete, you’ll undoubtedly train or race in hot conditions. Heat injury is one of the most dangerous injuries you’ll ever come close to. One of the reasons triathletes do get tripped by heat injury, particularly hyponatremia (when levels of sodium become dangerously low), is because they stick solely to water for fluid replenishment. Sports drinks, like Gatorade, have an appropriate amount of sodium within their mix, and not only replenish your sodium stores but help the body absorb water. In Ironman competitions, pretzels, soup, and other salty products may do well for you.

Study and apply good nutrition. Over the long haul — and triathlon is a long haul — good nutrition will pay dividends in longevity and performance. The great triathletes, like Dave Scott, Paula Newby-Fraser and Mark Allen, will tell you face to face that nutrition was a critical component in their health and strength, year after year, victory after victory.

Study and apply good nutrition. Over the long haul — and triathlon is a long haul — good nutrition will pay dividends in longevity and performance. The great triathletes, like Dave Scott, Paula Newby-Fraser and Mark Allen, will tell you face to face that nutrition was a critical component in their health and strength, year after year, victory after victory.

| 3.2 | The Knees |

It’s a true story from the days of the running boom, and it goes like this: A top collegiate distance runner reported to his coach in emotional shambles. He’d start off on a training run and would be reduced to limping and then to a sorrowful walk. He was struck with severe knee pain, he told the coach. Sharp, mysterious and relentless.

The coach sent him off to an orthopedic specialist. Without a visual cue to work with (there was no swelling, for example), the doctor performed a surgical operation. Following the surgery were months of rehab to recover the atrophied muscles that had shrunk during the procedure. The runner finally got to put on his running shoes and test it out. The same exact pain in the same exact part of the knee fired up as if untouched by the surgery. He still couldn’t run, and what followed was a repeat of the nightmare: another operation, months of therapy and with the exact same result: the pain resurfaced the moment he started to run.

Finally, the runner was referred to Dr. George Sheehan, the prototypical running doctor who eventually gained fame as a columnist for Runner’s World and author of countless books. The first thing Dr. Sheehan asked the young distance star to do was take off his shoes so he could look at his feet. (The injured runner thought Sheehan was nuts. “I said my knee, not my foot.”)

After a minute or so inspecting his patient’s feet and shoes, he took scissors to a piece of cork, and inserted the cork underneath the insole of the shoe. He had the young man put his shoes back on and told him to go for a jog.

The pain was gone.

The moral of the story is that when a knee injury from running occurs, we first need to dismiss the common concept of athletic knee injuries that happen to football and basketball players. “It’s awful rare that cartilage is going to be injured from running,” says Dr. Keith Jeffers, a chiropractor, exercise physiologist and veteran runner based in San Diego. Dr. Jeffers, a.k.a. “The Running Doctor,” says that knee injuries in football are likely caused by a leg getting twisted in a violent tackle. A runner’s knee problem, on the contrary, is rooted in a biomechanical flaw flushed out by the thousands of footsteps a runner or triathlete takes every workout. The flaw, oddly enough, has little to do with the knee itself; the knee is simply the unlucky victim.

The two most common knee pains that result from distance running are Runner’s Knee (peripatellar pain syndrome or medial patellar retinaculitis) and ilio-tibial band (ITB) friction syndrome. Symptoms of Runner’s Knee include a localized pain underneath or near the kneecap that appears early in a run, or climbing and descending stairs. ITB friction syndrome symptoms include a sharp pain that appears on the outside of the knee. Many veteran triathletes, particularly of the half- and full-Ironman variety, will have experienced either one or both of these knee injuries at some point in their careers. Both are biomechanical flaws triggered most often by mistakes such as upping one’s training mileage too drastically, too much racing, too much exposure to hard and cambered training roads, too much running on a track and footwear that’s not doing the job.

Learning the hard way is no fun. According to Dr. Jeffers, 25 percent of running injuries are of the knee pain variety. By following these tips, you will take valuable steps toward keeping yourself off the proverbial sideline.

Learning the hard way is no fun. According to Dr. Jeffers, 25 percent of running injuries are of the knee pain variety. By following these tips, you will take valuable steps toward keeping yourself off the proverbial sideline.

Correct the mechanics of the foot with an insole. “Research shows that 80-90 percent of runners have pronation problems,” says Dr. Jeffers. Runner’s Knee-type pains can often be solved-and prevented-with a simple correction to the runner’s shoe. He adds that almost all of us can benefit from purchasing a generic over-the-counter-type foot orthotic, such as Superfeet, that adds a solid dose of arch support to a running shoe. “An orthotic also helps tract and stabilize the heel,” he says. “When you tract the heel, you tract the knee.” For those wanting to go the extra mile, consider visiting a recommended running doctor or podiatrist for an evaluation of foot mechanics and tendencies. A good place to get a recommendation of who to see is at a running shoe store or through your local triathlon community.

Correct the mechanics of the foot with an insole. “Research shows that 80-90 percent of runners have pronation problems,” says Dr. Jeffers. Runner’s Knee-type pains can often be solved-and prevented-with a simple correction to the runner’s shoe. He adds that almost all of us can benefit from purchasing a generic over-the-counter-type foot orthotic, such as Superfeet, that adds a solid dose of arch support to a running shoe. “An orthotic also helps tract and stabilize the heel,” he says. “When you tract the heel, you tract the knee.” For those wanting to go the extra mile, consider visiting a recommended running doctor or podiatrist for an evaluation of foot mechanics and tendencies. A good place to get a recommendation of who to see is at a running shoe store or through your local triathlon community.

Massage the ilio-tibial bands. The ilio-tibial band is a strip of fascia that originates in the hip and wraps down along the outside of the thigh, inserting itself into the shinbone below the knee. A massage therapist working on a non-runner can be pressed to find any sign of this band. But in a runner, the band is pronounced and taut. The general consensus as to the cause of ITB friction syndrome is that the leg is overwrought with the pounding, and gets so tight that it inflames the insertion of the band to a point of grinding pain. Too much running on hard surfaces, or running downhill, can contribute to this dilemma.

Massage the ilio-tibial bands. The ilio-tibial band is a strip of fascia that originates in the hip and wraps down along the outside of the thigh, inserting itself into the shinbone below the knee. A massage therapist working on a non-runner can be pressed to find any sign of this band. But in a runner, the band is pronounced and taut. The general consensus as to the cause of ITB friction syndrome is that the leg is overwrought with the pounding, and gets so tight that it inflames the insertion of the band to a point of grinding pain. Too much running on hard surfaces, or running downhill, can contribute to this dilemma.

What’s a good way to prevent this syndrome? Post-workout stretches are often recommended to loosen up the band, but Dr. Jeffer’s warns that this can do more harm than good. “The best way to stretch the ilio-tibial band is through massage,” he says. Rather than yanking on the ends of the band with a stretch, an action that can mess you up with micro-tears, spreading out the band with massage techniques lengthens the band safely. Seeing a professional sports massage therapist once every week or two is the best way to do this, but you can also harvest benefits by having a partner press and massage along the band. Rolling your bodyweight along the band on foam rollers (easy to find in the modern-day fitness center) is another inexpensive way to self-massage the band.

Strengthen the hamstrings. “Many people think it’s the quadriceps that stabilize the knee, and they weight train these muscles to prevent knee injuries,” says Dr. Jeffers. But don’t forget the hamstrings, he warns. “It’s the hamstrings that actually do more work to stabilize the knee.” He recommends the following exercise: On your knees, either hook your heels underneath a couch, or have partner hold them down for you. Keeping your back straight, lean forward as much as you can, slowly, and return to the vertical starting position. Repeat. As your hamstrings grow stronger, you’ll be able to lean farther and farther forward. Along with helping you to prevent knee injuries, this exercise can help beef up the upper part of your hamstrings, another spot vulnerable to injury.

Strengthen the hamstrings. “Many people think it’s the quadriceps that stabilize the knee, and they weight train these muscles to prevent knee injuries,” says Dr. Jeffers. But don’t forget the hamstrings, he warns. “It’s the hamstrings that actually do more work to stabilize the knee.” He recommends the following exercise: On your knees, either hook your heels underneath a couch, or have partner hold them down for you. Keeping your back straight, lean forward as much as you can, slowly, and return to the vertical starting position. Repeat. As your hamstrings grow stronger, you’ll be able to lean farther and farther forward. Along with helping you to prevent knee injuries, this exercise can help beef up the upper part of your hamstrings, another spot vulnerable to injury.

Correct your strength imbalances. Along with correcting the biomechanics of the feet, analyzing and correcting the various imbalances surrounding your core muscle groups (abdominal, hips, back muscles) and the legs is vital. Consider getting a full-scale evaluation at a sports medicine clinic or from a running doctor to gain awareness of your weak points. They’ll usually prescribe specific exercises to get you back in balance. Exercise techniques, such as Pilates and core conditioning classes, are also appropriately useful for triathletes.

Correct your strength imbalances. Along with correcting the biomechanics of the feet, analyzing and correcting the various imbalances surrounding your core muscle groups (abdominal, hips, back muscles) and the legs is vital. Consider getting a full-scale evaluation at a sports medicine clinic or from a running doctor to gain awareness of your weak points. They’ll usually prescribe specific exercises to get you back in balance. Exercise techniques, such as Pilates and core conditioning classes, are also appropriately useful for triathletes.

Seek out smart running surfaces. If possible, run on trails for at least 50 percent of your run training. Avoid running on tracks except for interval sessions. When running on the road, beware of cambered surfaces — use flat, even roads and sidewalks when possible. Long, brutal downhills are to be avoided as well.

Seek out smart running surfaces. If possible, run on trails for at least 50 percent of your run training. Avoid running on tracks except for interval sessions. When running on the road, beware of cambered surfaces — use flat, even roads and sidewalks when possible. Long, brutal downhills are to be avoided as well.

Obey the slightest warning sign. We mentioned feelings of invincibility. What this usually leads to is egotistically thinking you can run through any pain tossed your way. Wrong answer. The best response to the slightest tinge of discomfort you can describe as musculoskeletal is to break out the ice bag and immediately get an evaluation as to what might be going on. Do you need new running shoes? Have you been stretching and strengthening? Do you need to lower your mileage? Immediate precautions include icing for 10 minutes before and after a run, and consider focusing your training on biking and swimming for a few days.

Obey the slightest warning sign. We mentioned feelings of invincibility. What this usually leads to is egotistically thinking you can run through any pain tossed your way. Wrong answer. The best response to the slightest tinge of discomfort you can describe as musculoskeletal is to break out the ice bag and immediately get an evaluation as to what might be going on. Do you need new running shoes? Have you been stretching and strengthening? Do you need to lower your mileage? Immediate precautions include icing for 10 minutes before and after a run, and consider focusing your training on biking and swimming for a few days.

Responding to the body’s signals with this kind of ferocity, and using all the preventative tips mentioned, will help you make strides toward a more true invincibility.

| 3.3 | The Chronic Muscle Tear |

How to Treat the Injury that Drives Runners and Triathletes Crazy

“The chronic muscle tear is probably the third most common injury among all groups of runner,” writes Dr. Timothy Noakes, the quintessential runner/doctor in his encyclopedic work The Lore of Running.

I came across these words in my own frantic quest for an answer to a hamstring injury that had plagued me for nine months. The words that leaped up at me from off the page were the following:

“Chronic muscle tears are usually misdiagnosed, can be very debilitating and will respond to only one kind of treatment. The characteristic feature is the gradual onset of pain, in contrast to the acute muscle tears dramatically sudden onset of pain.” This characteristic matched my problem exactly.

“In contrast to bone or tendon injuries, both of which improve with sufficient rest, chronic muscle tears will never improve unless the correct treatment is prescribed.”

Noakes’ book rang another bell for me here, as I had tried taking days off, and later weeks with no running, only to lace up my shoes, hit the road and feel as if, in terms of my injury, an hour hadn’t passed. Noakes goes on to say that he was witness to one runner who had struggled with a chronic tear for five years.

Noakes advises that you can identify a chronic tear with the help of a physiotherapist, having him or her plunge two fingers deep into the location of the pain and search for a hard and tender knot. Noakes states that if a knot is found, then you’re dealing with a chronic tear. In my case, the knot was very easy to find, deep in the belly of the left hamstring and hard as a marble.

Noakes believes that, while the mechanism behind a chronic tear is unknown at this point, specific sites on the body that digest large amounts of pounding (from running mileage), overuse (an endurance-sport given) and high-intensity loads (from speed or power training) are the areas most likely to sustain this type of injury.

Noakes observed that chronic tears tend to show their ugliness when an athlete makes an increase in mileage and/or intensity. In my case, I could jog around forever without much problem, but when I tried to run at any speed faster than a seven-minute pace, I found myself rapidly reduced to an infuriating limp.

“Conventional treatment, including drugs and cortisone injections, is a waste of time in this injury,” writes Noakes, and he goes on to illustrate the technique he deems effective: cross-friction muscle massage, a physiotherapeutic technique detailed in the 10th edition of the British Textbook of Orthopedic Medicine.

The maneuvers are applied directly to the injury site, perpendicular to the injured muscle, and must be applied vigorously. “If the cross-friction treatment does not reduce the athlete to tears, either the diagnosis is wrong and should be reconsidered or the physiotherapist is being too kind.”

Five to 10 five-minute sessions of cross-friction should correct the problem, says Noakes, but more may be necessary depending on how long the athlete has had the injury.

Runner’s World’s Dr. George Sheehan had once forwarded a desperate letter to Noakes from a runner who had tried everything to overcome a chronic muscle tear, having suffered from the tear for more than a year. Noakes wrote to the runner, advising him of the cross-friction techniques. He also suggested that he stay away from static stretching exercises, as it would only exacerbate the problem until it was sufficiently healed.

As I mentioned, when I found the Noakes material, I had made no progress whatsoever in getting effective treatment. Within a week of cross-frictions and no stretching, I observed a substantial and positive change in the strength within my hamstring. A month later, I was able to perform speed workouts again without deteriorating into a limp.

Once a chronic muscle tear has been tamed, an athlete should work aggressively to prevent a recurrence of the problem.

Incorporate a quality weight-training program into your training schedule, include moderate amounts of stretching. Upon noticing the first hint of reinjury, immediately apply more cross-frictions.

“A little treatment early on in these injuries saves a great deal of agony later,” Noakes says.

| 3.4 | Taking to the Trails |

As mentioned earlier, one of the best ways you can make strides in the injury-prevention business is to do a steady proportion of your running on trails. The lower impact stress and the variety of terrain not only helps prevent injury, but gives you an enhanced training effect. Trails are also one of the most addicitive places to run. Scenic beauty, peacefulness, and fresh air.

| 3.5 | Building Core Strength for Multisport |

Canadian Donna Phelan is a professional Ironman triathlete and certified personal trainer based in Encinitas, California.

Written and designed exclusively for this book, we asked Donna to develop an accessible core fitness program for the new triathlete or the veteran triathlete new to this brand of training (some the most hard-bodied triathletes will fail completely with certain simple tests of core strength and core balance, a condition that leaves them vulnerable to injury and power drain).

The following is Donna’s prescription:

The core is one of the most important sources of physical strength, but one of the most neglected areas by triathletes. The centralized “core” area is the center of the body and the beginning point for movement. It refers to the lumbar-pelvic-hip complex, a pillar between the upper body and lower body.

A weak core leads to inefficient movement and predictable patterns of injury. That weakness causes undue stress on peripheral muscles of the upper extremity and lower extremity.

A core stability program will help you gain strength and a greater biomechanical advantage for swimming, biking and running. The following are some basic core exercises that will benefit triathletes. With each of these exercises, they should be performed comfortably and pain-free.

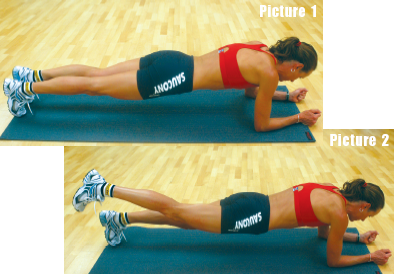

Begin by lying face-down on the floor with feet together and forearms on the ground, shoulder width apart (Picture 1).

Draw the abdominals inward, squeeze your glutes and lift your entire body off the ground, forming a straight line from head to toe — envision your body as a plank of wood. Hold for a length of time that is challenging but comfortable. Begin with two sets, advancing to as many as five to 10 sets.

When you’ve mastered the plank, the next step is to add hip extension (Picture 2). Begin by performing the plank, then extending one hip at a time by activating the glutes and lifting your leg three to four inches off the ground. Hold for five to 10 seconds, then slowly return the starting position and repeat with the opposite leg.

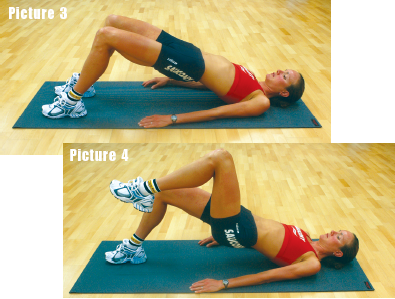

This exercise helps develop muscle recruitment and firing of the glutes. Start by lying on your back, with your knees bent at 90 degrees and feet flat on the floor (Picture 3).

Contract your glutes and raise your hips toward the ceiling, forming a straight line between your hips and shoulders. The only point of contact with the ground should be your feet, shoulders and head. Maintain a strong glute contraction and hold for 10 seconds. Lower your hips to the floor and repeat three to five times.

An advancement of this exercise is to add “marching,” one leg at a time (Picture 4). Simply raise one bent knee while in the bridge position and hold for three to five seconds. Alternate legs and repeat three to five times.

Begin on all fours with your abs drawn in and your chin tucked toward your chest (Picture 5).

Slowly raise one arm (with your thumb pointing up) and at the same time lift the opposite leg.

Keep both your arm and leg straight while lifting them to body height. Hold for five to 10 seconds, and return your arm and leg to the ground.

Repeat with the opposite arm and leg, and perform three to five repetitions.

The objective of this exercise is to build mobility and strength in your torso by eliminating the use of your hips and shoulders.

Begin by lying on your back, arms extended out at your sides, knees bent and feet flat on the floor. Raise your lower legs to a 90- degree hip position (Picture 6) and slowly lower them to one side until they reach the floor (Picture 7). Raise them again to the starting position and lower them to the opposite side (Picture 8).

Remember to keep your abs drawn in and your torso and shoulders in contact with the ground. Begin with five repetitions to each side.

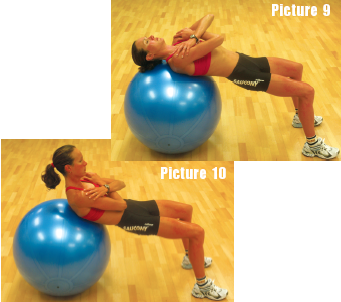

This is a variation of the standard crunch done on a flat surface. For this exercise you will need a stability ball.

Begin by lying on your back, arms folded across your chest (Picture 9). Be sure your knees are bent at a 90-degree angle and feet are flat on the floor, toes pointing straight ahead.

Draw your abs in and slowly crunch your upper body forward, raising your shoulders off the ball, and chin tucked toward your chest (Picture 10).

Hold for two to three seconds, then return to the starting position. Repeat five to 10 times.

For more information on Donna’s training, go to her website at www.ipushfitness.com.

| 3.6 | Generating a Foundation of Health |

Formerly a national-class pole vaulter AND sub-2:30 marathoner, Ken Grace is a top California-based track coach, who has worked with everyone from the junior college distance runner to national-class marathoners and triathletes.

A longtime student of kinesiology and exercise science, Ken loves pushing the envelope of applying fresh research to helping his athletes perform at their best, and to stay healthy doing it.

In the following chapter, Ken boils down some of the principles he holds essential for achieving and maintaining athletic excellence and health.

Principles to Follow If You Want to Improve Your Physical Performance and Your Well Beings

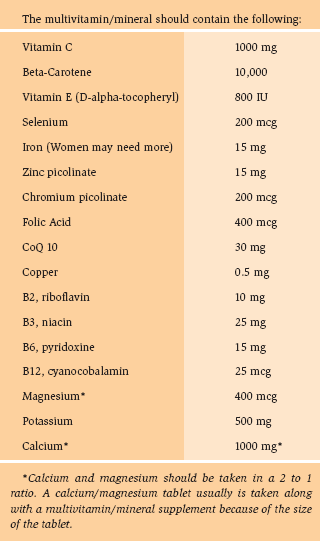

1. Eat Breakfast. Start your morning with a 12-ounce glass of water. Then eat a nutritious breakfast that includes a piece of fruit, protein, low-glycemic carbohydrates and a multivitamin/mineral supplement.

A tablespoon of flaxseed oil, or two tablespoons of ground flaxseed mixed with juice, helps to supply the essential fats (Omega 3 and Omega 6) in the proper proportions.

People who eat breakfast on a regular basis have a higher lean mass and feel better throughout the day.

2. Try to Eat 5 or 6 Small Meals Each Day. The goal is to keep your blood sugar constant throughout the day. This is accomplished by eating something every two hours or so. After a good breakfast have a snack at around 10 am that includes fruit, a low glycemic carbohydrate and water. People, who eat lots of small meals keep their blood sugar level constant without any big highs or lows. In the long run, a consistent blood sugar, combined with a good exercise program, leads to fat loss and a growth of lean mass. Use your snack time to increase your fruit and vegetable intake for the day. Five meals a day would be: Breakfast, a morning snack, Lunch, afternoon snack & Dinner. If you have a snack after dinner try to make it a high protein/low fat snack before 8 pm.

3. Drink 8 to 10 Glasses of Water Daily. Water is the medium for every chemical reaction in the body. When you are dehydrated your body does not adapt and improve efficiently. In addition to drinking water, we are supposed to get a great majority of our water through a high daily intake of fruits and vegetables. Our natural mineral and vitamin demands are supposed to be met through the intake of fruits, nuts and vegetables.

4. Don’t Spike Your Insulin. This is done by eating foods that are low in Glycemic Index and eating lots of small meals. Avoid high glycemic foods like French fries, sodas and simple sugars.

5. There are No Quick Fixes. Once you start a sound nutrition program...stick with it. It takes time to grow things right! It takes a good 3 to 6 months for all your cells to adapt and grow stronger. A red blood cell lives for 90 days before it is replaced. Make sure the protein you eat is sufficient first class protein and not a burger and fries!

A whey protein isolate drink is something to consider. Fish that live in cold water like Salmon, Tuna or Mackerel are excellent sources of protein. You need a protein source that is low in saturated fat!

6. Take Essential Fats Daily. Omega 3 and Omega 6 oils are essential to good health. Your cells need these fats on a daily basis for cellular metabolism. Flaxseed oil, olive oil and fish oils are examples of good fats. A daily tablespoon of flaxseed oil meets this need.

7. Avoid Partially Hydrogenated Oils and Saturated Fats. These are not good for your health. And they are definitely not essential fats. They are hard for your cells to metabolize. Saturated fats and partially hydrogenated oils are solid at room temperature. The essential fats are liquid.

8. Avoid Eating Chemicals Made by Man. Avoid eating or drinking food that contains Aluminum. Aluminum is a man made alloy that has no purpose being in the body. Recent studies suggest that excess aluminum in the body causes a number of disorders. Avoid drinks or foods that come packaged in aluminum. Check your deodorant and toothpaste. Try to eat foods that are in natural state and unprocessed. Remember good food spoils quickly. If it has a long shelf life...BEWARE!

9. Be Active. Do something active everyday. This could be as simple as a 20 minute walk, or run, at 70% of your maximum heart rate or a 40 minute weight training routine. The key is to move daily on a consistent basis.

10. Eat Lots of Vegetables and Fruit. The U.S. Government says five servings per day. Ancient man ate more like 10 servings per day... and we are direct descendants. Our fiber intake, along with minerals and vitamins, comes mainly through fruits, nuts and vegetables. We need 30 to 50 grams of fiber daily.

11. Stretch and Relax Everyday. Take time to do some stretching everyday to lengthen your muscles and relieve tension. Hold each stretch for 30 to 60 seconds and do not bounce. Finish with 10 to 20 minutes of relaxation, focusing on your breathing.

For more training suggestions from Ken, visit his website at www.coachkengrace.com.