CHAPTER 3

STOP THE STORY!

Close your mouth and wipe up the soda you spit in your lap.

I KNOW. I KNOW.

How could the son of the greatest football player ever be a kid who hated sports, got a Batman head stuck in his nose, and accidentally beaned his teacher with a dodgeball?

I wish I could tell you, but I don’t have a clue. My mom doesn’t have a clue. The millions of my dad’s fans don’t have a clue. And my dad doesn’t even have a clue of a clue.

Let me paint a picture of just how weird this is.

My dad is handsome, muscular, confident, and a super-jock. From pretty much the moment he was born, people started putting balls, bats, rackets, and any other kind of sports equipment into his hands. Girls have gone crazy for him his whole life and guys wish they could be him.

My mom played point guard in the WNBA, set a bunch of track-and-field records, and won a bronze medal at the Olympics.

So, when the two of them had a kid, every sports site in the world called me the “Next Big Superstar” and reporters camped outside the hospital to get my picture.

Only big surprise, instead of a super-jock, I turned out to be a doofy-looking klutz with big ears, hair that looks like I just rolled out of bed, a habit of coming up with weird inventions, and ZERO athletic ability.

I trip over my own feet, throw a ball like an out-of-control duck on a roller coaster, and couldn’t win a race if the other runners were blindfolded and I got a head start. I completely freeze up around girls, and the only sports competition I’ve ever won was a third-grade hot dog eating contest.

Some kids might be embarrassed about being such a complete failure of an offspring. They might try changing their name. Or moving to a different planet. They could even accidentally lock themselves in the bathroom while listening to really loud emo music after their dad’s fourth Super Bowl win. (Don’t ask.)

But not me. I’m totally cool with being such a disappointment. At least most of the time.

On the TV, Dad clasped his hands above his head and waved to the crowd as he promised the citizens of Earth that their debt to the aliens would be paid off in no time.

It turns out his promise was mega-premature.

On a table next to the microphone was a contract as thick as twenty of my school math books piled together. For the last three months, Earth’s lawyers had examined every section to make sure the competition would be fair. Alien teams were limited to generally nonlethal players who were no more than twice as fast, or three times as strong, as humans. No interdimensional teleporting or mind melding was allowed on the field. And eating other players was against the rules.

Having to make a specific rule against eating other players didn’t sound like a great start to a sports tournament. But with my dad leading the Earth team, I didn’t see how we could lose.

After each of the world’s leaders signed the last page, an alien walked to the table with a sly grin and signed the contracts on behalf of the fifteen alien teams.

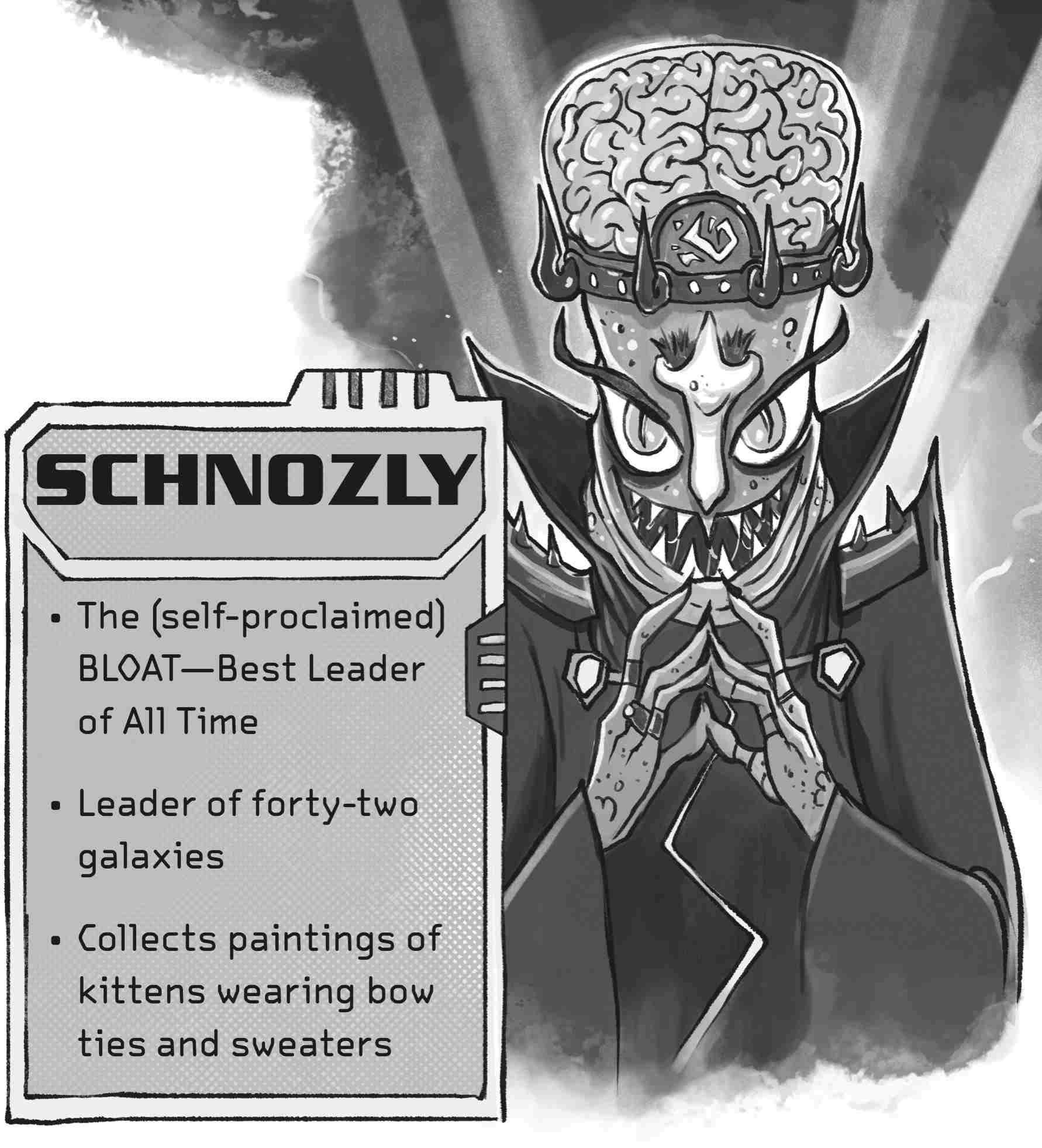

His name was Schnozly Grofsplot. He had an upside-down nose, pointed teeth, and his brain floating in a jar like something out of a really bad horror movie. Schnozly was the one who organized the Quantum Interstellar Sports League and drafted the contract Earth’s leaders had just agreed to.

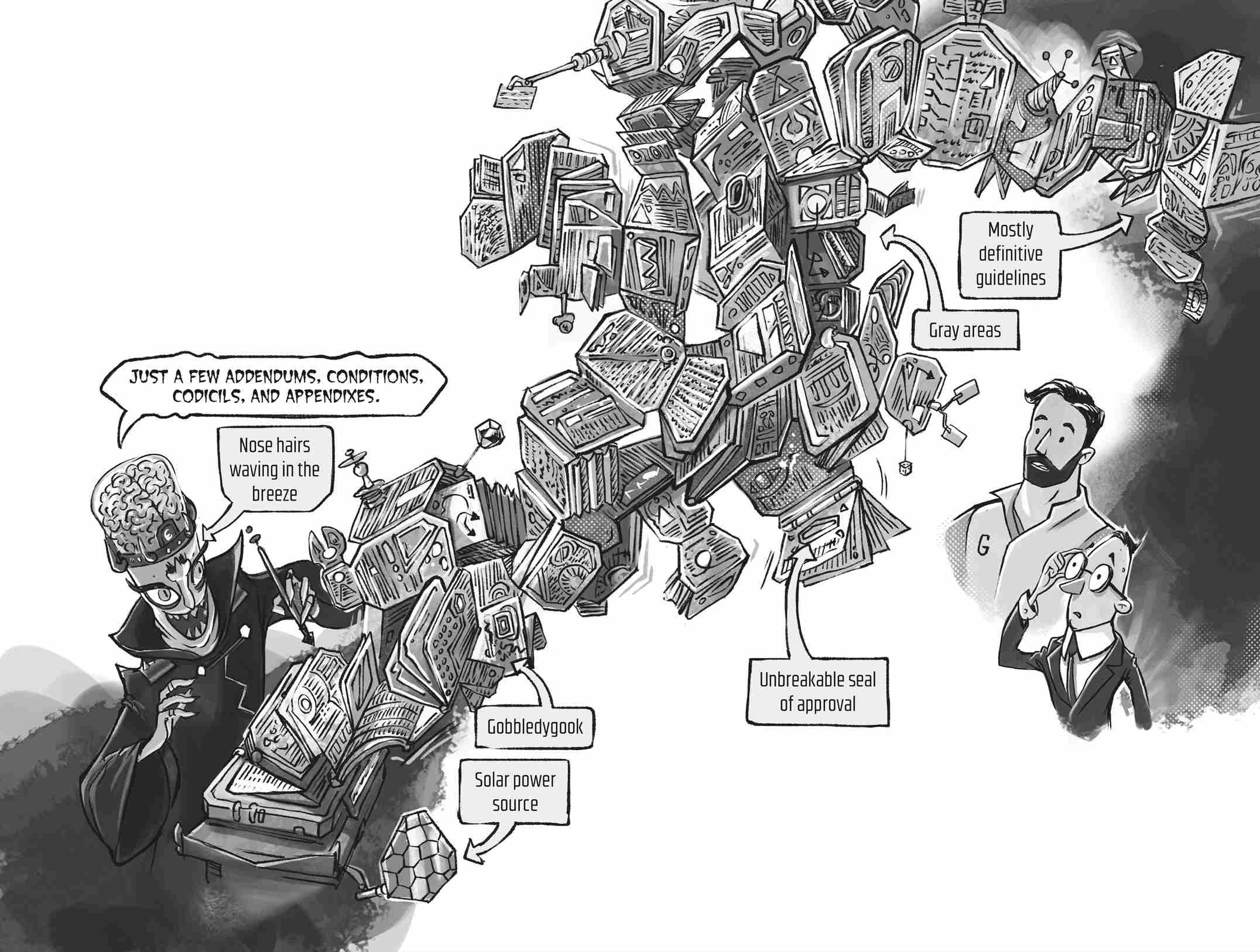

But the minute he lifted his pen from the page, the contract began to change—twisting and turning on the table as buttons, levers, knobs, and alien gizmos sprang out.

“What’s going on here?” squeaked a nervous-looking lawyer with thick glasses and hair that looked oily enough to grease a bike chain. “Is this normal for alien contracts?”

He anxiously studied the new additions, but the alien leader only smiled.

Schnozly pushed a lever that made the contract spin and tapped a newly revealed page. “Just one more teensy-weensy, completely minor thing. In reference to part three, subsection A, addendum thirteen, we, the assembled alien nations, limit Earth’s team to nine human players under the age of fourteen and five aliens of the same age currently living on the planet.”

There was complete silence as the alien’s words sunk in.

The BLOAT pushed another button and the contract flipped over. “Also, all of Earth’s debts will be canceled if you win, as discussed. But if you lose, you must immediately pay your bill in full.”

He took out a holographic calculator. “Including all the items you illegally took, plus galactic collection services and taxes, multiplied by the standard interstellar interest rate of 116 percent, the total comes to…”

One of the politicians fainted, and a reporter in the front row shouted, “Why do you want our planet?”

Schnozly Grofsplot held up his long multijointed fingers, counting off the reasons. “It’s the perfect location to build my six millionth intergalactic fast-food restaurant, humans will provide cheap labor, your oceans contain water that we greatly desire, and I’ve become quite fond of your kittens.”

My dad looked like he’d just eaten a dung beetle.

After a month of worldwide panic and tons of political meetings, Earth’s leaders finally admit that we’ve been hosed. Unlike the NFL, where teams are allowed up to forty-eight players, QISL teams are limited to fourteen. They decide to pick the nine best kids—and five young aliens living on Earth—and hope for the best.

On the day of the draft, every student, teacher, and faculty member of Dry Creek Middle School is sitting in the cafeteria, waiting to learn who will play for the team that has been named the Planet Earth Defenders.

That’s me over there.

No, not the one in the football jersey.

Not the one eating the hamburger and looking up sports stats on his phone.

Definitely not one of the kids whispering about which of the announcers on the giant TV screen at the front of the room has the cutest eyes.

I’m the one way in the back, eating a bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, drinking a W00t!, and reading a book about odd inventors of the nineteenth century. It’s not like I want to be here, but all anyone’s been talking about since Earth’s politicians realized there’s no way out of the contract is which nine kids will be drafted. All our classes have been canceled to watch the announcement.

Up on the screen, the football draft starts.

I try to ignore what’s happening, but with everyone around me oohing and awwing over every new name, it’s hard not to at least look up.

The first part of the draft is reserved for the aliens, who include a four-tentacled octopus, a cool bat-girl, and a bunch of other creatures who—considering the limited number of aliens living on Earth—don’t seem too bad.

Next is the part everyone’s been waiting for—picking the nine lucky unlucky kids.

Most of the sports analysts have been predicting the committee will pick the top nine under-fourteen football players in the country. Instead, they choose athletes from around the world known for other sports: a cocky South American soccer star, an overly cheerful ballet dancer from the UK, and a muscular Japanese baseball player.

As they continue announcing players, I go back to reading my book until a gasp from the crowd makes me look up at the TV and into the eyes of the most amazing girl I’ve ever seen. According to the headline, she’s a Filipino gymnast, but when I look at her, all I see is fire and confidence.

I’m so blown away by her supercool blue faux-hawk that I barely notice when they announce the last pick.

It isn’t until someone says my name that I realize everyone in the room is staring at me. That’s when I see my face on the TV. Not a picture of my face, but my actual face right now.

A camera zooms in on me as a reporter runs through the cafeteria and holds out a microphone. “How does it feel to be the ninth human chosen to play football for the fate of the Earth?”

Sure this is all a big mistake and wondering how the reporter got here so quickly, I gulp a swig of W00t!, trying to wash down a Cheeto that’s stuck in my throat, but only end up choking myself more. I cough and manage to gasp, “Don’t. Ask.”

Back in the cafeteria kitchen, Gertrude, the Hungarian lunch lady, drops a vat of mashed potatoes on the floor and shakes her head.