With most UFO sightings, you are left with only the witness testimony, and, if you are lucky, the witnesses don’t know one another so that one can then provide corroboration for the other. Sometimes there are photographs that can be analyzed, and sometimes there are radar contacts with photographs of the radar scopes. And sometimes there are physical traces left behind when the craft takes off. This provides something real and tangible that can be measured and sometimes with residue that can be taken into the laboratory and analyzed.

With the Socorro landing, there was additional physical evidence to be found on the ground. Once the object had taken off, Zamora walked a short distance into the arroyo where the craft had been sitting. According to Ray Stanford, “It seems to have both excited and frightened Zamora a little when he saw that the bushes were smoldering and smoking in several places.”1 That was the first indication for Zamora that there would be some sort of physical evidence of the UFO landing.

The landing site on the south side of Socorro, taken within hours of the landing. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

After Chavez arrived on the scene the two of them walked to the edge of the arroyo. Coral Lorenzen wrote, “[They] looked at the ground where the object had landed. It was still smoking. Several clumps of range grass were burned, as well as a stubby mesquite bush.”2

This information was also part of the Project Blue Book file on the case. In an unsigned document titled “Narrative of Socorro, New Mexico Sighting, 24 April 1964,” the unidentified writer noted, “Sgt Chavez was skeptical of the situation and proceeded to where Zamora had observed the object. Here he found the marks and burns. Smoke appeared to be coming from a bush which was burned but no flame or coals were visible. Sgt Chavez broke a limb from the bush and it was cold to the touch.”3

That wasn’t, of course, the only physical evidence. On the landing site, they found four impressions in the dirt and sand. Lorenzen wrote, “There were four 8 X 12–inch wedge-shaped depressions, 3 to 4 inches deep arranged in an uneven rectangle. There were also four circular depressions about 4½ inches in diameter and approximately 3 inches deep not far from one point of the large indentations.”4

Ray Stanford gives the credit for the discovery of the impression to Chavez. Chavez, down on the landing site, found a quadrangle apparently made by the landing gear that Zamora had seen. According to Stanford, these were made by something of great weight.5

Within hours of the sighting, Holder and Byrnes were on the landing site. They had interviewed Zamora and then, riding in the same car, headed out. According to Holder’s report in the Blue Book files, “Enroute (Mr. Byrnes and I went in the same vehicle) we stopped by the residence of Sgt. Castle, NCOIC [Non-Commissioned Officer In Charge] SRC M.P., who then accompanied us to the site and assisted in taking the enclosed measurements and observations. Present when we arrived were Officer [name redacted], Officers Melvin Ratzlaff, Bill Pyland, all of the Socorro Police Department, who assisted in making the measurements.”6 Hynek would later report that Holder “had done a good job procuring measurements and other data before the coming of the crowd of curiosity seekers.”7

Lorenzen reported, “Holder and the FBI man [Byrnes] came out to the site, took measurements, and the FBI man piled rocks around the indentations to preserve them.”8

Included in the Blue Book file was a diagram that suggested something of a trapezoid area, with the four depressions at the four corners. Also noted was an area that was described as footprints, but these are the circular depressions that Coral Lorenzen had mentioned. Some believed these might represent holes made by some sort of ladder that allowed the two beings to exit and then reenter the craft.

J. Allen Hynek was on the scene within a few days of the sighting. In his report back to Blue Book, he said little about the landing traces, other than that Holder and Byrnes had thought the markings were fresh. Moody reinforced this in his report, writing, “Further he [Chavez] stated that the marks were definitely ‘fresh’, and the dirt showed evidence of ‘dew’ or moisture.”9 This all suggests that they were made by the craft. He didn’t provide a description of them, but then other documents in the files did.

In another of the reports in the Blue Book files, one that was also probably prepared by Sergeant David Moody of the Blue Book staff, who happened to be in Albuquerque at the time, there is a little more about these impressions. He wrote, “There was no evidence of markings of any sort in the area other than the shallow depressions at the location where Mr (sic) Zamora reported the sighting.”10

At the time of the first search, a sweep was made to determine if there was any excess radiation in that area. Nothing was found to suggest that there was a higher than normal level of background radiation on the site. Zamora, and those who arrived shortly after the craft had departed, never exhibited any signs of a sunburn or sickness due to radiation.

According to Hynek, in a report about his trip made in March 1965, he was interviewing Socorro residents and the topic of a movie came up. This film was supposedly being made by Empire Studios about UFO sightings and the Socorro landing was one of them. Hynek wrote, “One rather interesting item is that the burning bush has recently exuded some sap, and one of the movie people took this to Los Angeles to have it analyzed and found it radioactive!”11

The next day, before all the tourists arrived, and all the other UFO investigators arrived, photographs of the site were taken. These included pictures of the landing impressions and the partially burned bush. The photographs were attached to the Blue Book file of the case.

Given that there were both law enforcement and government officials on the scene within a few hours of the report, and given that the witness (Zamora) could take them to the exact location, soil samples, fragments of the burned bush, and several samples of metal that might have come from the landing gear were taken. Some of this would erupt into controversy with the private UFO investigator and one of the national, civilian UFO organizations involved.

The Blue Book files contain notes made about a telephone call between Captain Theodore W. Cuny of the 1005th Special Investigation Group in Washington and Major K.S. Sameshima. That information apparently was communicated to Cuny by Lieutenant Colonel King of the Counter Intelligence Division, who, in turn had read about it in an Albuquerque newspaper. One of the interesting things about it was this:

Upon being informed of this, the Army (a Captain R T Holder of White Sands) roped off the area. Also the FBI at Albuquerque proceed to the area, and allegedly confirmed that “something” had been there. They reportedly found 4”x5” impressions in the ground somewhat like the stand legs; the impressions appeared burned. The newspaper stated that the Army took soil samples.12

These samples, according to the information available, were given to Hynek when he arrived late on Tuesday (April 28). This seems to explain why Hynek wasn’t prepared to collect samples himself when he was there. He had the samples taken that first night by Holder before the site had been compromised by others including tourists and curiosity seekers.

Ray Stanford reported that when he arrived at the landing site on Wednesday, Hynek was already there with a number of others. They inspected the scene, which had been visited by many people in the days after the story made the news. Stanford began to take soil samples, and according to him Hynek asked for some of the small vials so that he could take samples as well.13 These would have been in addition to those that Harder had collected and given to him earlier.

According to the Blue Book files, “Laboratory analysis of soil samples disclosed no foreign material.... Laboratory analysis of the burned bush showed no chemicals which would indicate a type of propellant.”14 That was just a fancy way of saying they found no evidence of gasoline, lighter fluid, or any other chemical that could have been used to set the bush on fire. That ruled out one of the elements of the hoax.

Blue Book also contains an Evaluation Report dated May 19, 1964, that amplified this information. The report said, “Spectroscopic analysis indicated the gross composition to the same for all samples.... There is apparently no significant differences in elemental composition between different samples.”15

Hynek also wrote, “They [NICAP and APRO] will probably say that the burns are ‘plasmaburns’ [sic] which can scorch locally, I understand.”16 I have found nothing to suggest that either organization ever made such a claim.

That wasn’t all that had been found. Sand that had apparently been subjected to high heat, that is vitrified, was reported on the site. Dr. James McDonald, a University of Arizona physicist, wrote to Dick Hall, then of NICAP:

Briefly, a woman who is now a radiological chemist with the Public Health Service in Las Vegas [Nevada] was involved in some specific analyses of the materials collected at the Socorro site, and when she was there, the morning after, she claims that there was a patch of melted and resolidified (sic) sand right under the landing area. I have talked to her both by telephone and in person here in Tucson recently.... I must say, it’s very hard to imagine how such material could have been there not only on the evening of the 24th but still there on the morning of the 25th without it[s] ever having been reported before.... She did the analyses on the plant-fluids exuded from stems of greasewood and mesquite that had been scorched. She said there were a few organic materials they couldn’t identify, but most of the stuff that had come out through the cracks and blisters in the stems were just saps from the phloem and xylem. Shortly after she finished the work, Air Force personnel came and took all her notes and materials and told her she wasn’t to talk about it anymore.17

As Jerry Clark noted, there is no mention of this anywhere else. There is nothing in the Blue Book file about it. None of those who were on the scene that night or the next morning made any mention of it. McDonald did not identify his source on it, but then, the Socorro case involves any number of unidentified sources (which is one of the major problems not only with this case but many UFO cases).

Stanford does, however, point to additional and possibly corroborative information for McDonald’s report. According to him, when he was told by a police officer about one of the rocks, an Air Force officer standing near the center of it looked down at what Stanford said was a large rock that had a “bubbly looking” surface. He questioned Zamora about the actual landing site and examined the other rocks in the area, but they didn’t look the same. Portions of the rock had a glassy surface, which seems to suggest that high heat had been applied in the area causing some of the sand and silicon material to melt, running together and creating a melted patch to which McDonald had referred.

According to Stanford, “Shortly thereafter the officer stood up and made notes on the location of the vitrified object...and about how it differed from natural rocks in the area.”18

Stanford reported that he dismissed the story when he first heard it but later, after learning of the McDonald letter, and hearing it from reliable police sources, he believed that this important information had been concealed from the public. He could learn nothing more about this and no evidence of this sort appeared in the Blue Book files.

The most controversial aspect of the physical evidence is that found on some of the rocks on the landing site. These small, almost-microscopic fragments were embedded on the rocks where the landing gear had scraped them. They were collected and analyzed; in the end, it was one of those “who do you want to believe?” situations.

The Blue Book files contains no reports on the analysis of any metal fragments. It doesn’t seem that any were actually collected by any of the military personnel on the scene or by other official representatives including Byrnes and Hynek.

Stanford seems to indicate the same thing when he was on the site with Hynek, Zamora, and Chavez on the Wednesday after the landing. Stanford, in searching the site, had seen a rock on which one of the object’s landing gear had apparently scraped. He tried to ignore it so that others wouldn’t realize the significance of it. With the others, he left to attend the press conference that Hynek was going to hold, but the instant it was over, he headed straight back to the landing site.

The rock was still there and Stanford carefully collected it. Stanford’s background includes the collection of dinosaur samples, so that he was not unfamiliar with the proper procedures. Before he removed it, he studied it, photographed it, and observed its relation to the other rocks and impressions on the site. He noticed abrasions on the stone that looked to be metallic. These could represent important evidence of what Zamora had seen and what had landed there.

With no real trouble, Stanford was able to get the stone to his car, carefully wrapped in case some of the very small metallic fragments fell away because of the handling. On May 3, 1964, he wrote to Dick Hall and the controversy began. He wrote, “Metal traces on rock… are very minute [italics in original], but sufficient for analysis & may give us the physical evidence [italics in original] we’ve been waiting.”19

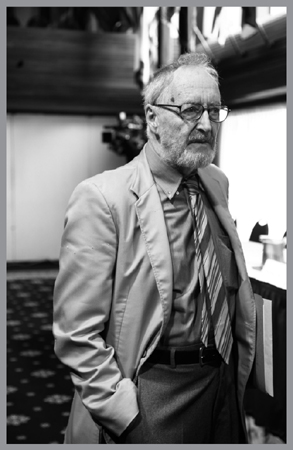

Richard Hall, who was directly involved in the attempted analysis of the metal fragments. Copyright CUFOS. Photo by Mark Rodeghier.

But there was a new problem: Stanford, excited about what he had found, showed it to a Phoenix doctor. They had been outside when Stanford showed him the rock. The doctor went inside for a magnifying glass and when he returned, he held out his hand. Without thinking about it, Stanford gave the rock to the doctor and then realized that he (the doctor) put his hand on the spot where the biggest and possibly the best of the metallic slivers were. Upon examination, they realized that the majority of the residue was gone.

They tried to find the slivers using a magnet but they had no luck. Stanford had to write to Hall explaining that he had lost the best of the material. There was some residue left and that small amount might be enough for a meaningful analysis. It least that was what he hoped.

Hall thought that NICAP scientific consultant Walter Webb would have the best luck in getting the small samples analyzed. Stanford disagreed, and this resulted in a number of letters being exchanged until Hall wrote that he had scientists at the Goddard Space Flight Center interested in analyzing the metal fragments.

The details were eventually worked out, and Hall identified his contact as Henry Frankel, a former believer in UFOs but who was then more skeptical. At Goddard, Frankel was shown the rock and, according to Webb, the sight of the rock was discouraging. Frankel, however, wasn’t above trying and sent them all to a cafeteria while he made his examination, promising to save half the remaining slivers.

When Frankel didn’t return, the group—that is Hall, Stanford, and Webb—went in search of him. Frankel was gone and the lab was empty except for a technician. The rock had been scraped clean, according to Stanford, but the technician claimed that some of the scrapings were still available. Stanford, however, disagreed, said that they were just the “pseudometallic refractions from crystals.”20

That wasn’t the end of it. Frankel did return and said there were be additional tests made. He would have the results on the following Wednesday.

Then the story, according to Stanford, descends into the paranoid. Stanford, with his friend Robert McGarey, a Navy captain, who is identified with a pseudonym, went out to dinner. The captain told them that they were being naïve, suggesting that the government would never allow them to retain any evidence that would prove the extraterrestrial nature of UFOs. He hinted that the government knew that UFOs existed and in this context obviously suggested that they were alien. The captain sort of mocked Stanford by telling him that they had just given away their evidence.

According to Stanford, the captain said:

Those boys at Goddard know that they must report any findings as important as a strange, UFO alloy to the highest authority in NASA. Once that authority receives the news, the president will be informed, for the matter is pertinent to national security and stability.... Frankel may privately tell you of his findings, but when it comes down to brass tacks, they can never verify any important test results, officially.21

Stanford then asked, “You mean that the physical evidence of the Socorro UFO is, in effect, lost to the world?” The answer was “absolutely. This shows how little you do-it-yourself revelators of UFO facts really know. You just gave your evidence into the hands of what you apparently consider the enemy.”22

On Wednesday morning, Stanford called Frankel. Jerry Clark noted that Frankel’s comments are in quotation marks even though Stanford had not recorded the conversation. He had taken notes of it. Frankel told Stanford that the particles were not natural. “They were a zinc-iron alloy with other trace elements; based on the extensive charts Goddard possessed, Frankel could state with confidence that the alloy was unlike any known to be manufactured on earth.”23

To reinforce the point, according to Stanford, Frankel said that he thought this meant that the object seen by Zamora could have been manufactured on another world. This was, of course, an unbelievable conclusion by a scientist at a nationally recognized laboratory. To make it even better, Frankel said that he would pass the information along to Hall.

Hall, being the cautious sort, and afraid of burning important bridges, suggested that Stanford go easy in his discussions with Frankel and those at NASA. He didn’t want Frankel pressured. When Stanford called a week later, Frankel wouldn’t take that call, or any other calls made over the next several days and then several weeks.24

Then, to make it worse, another man, Thomas P. Sciacca, Jr., whom Stanford had met during the visit to Goddard, said that Frankel was no longer involved in the project and that he had been in error with his conclusions. If there were complaints, Sciacca would handle them, but only if they were put into writing.

On September 11, 1964, a formal statement of the analysis was forwarded to Hall. It was meant to end the confusion about their findings and to set the record straight. That information was published by NICAP in their newsletter:

The shiny substance found on a rock adjacent to one of the imprints left at the Socorro, N.M. landing site has been identified as Silica, according to a report from a top Washington laboratory. Silica is a very common substance (quartz and sand are forms of it). These results threw cold water on the hope that objective physical evidence had been found in the form of metal....

In the previous issue, we reported the finding of the substance by Ray Stanford, NICAP member authorized to investigate this case, as he and the witness Ptn. [Patrolman] Lonnie Zamora, examined the imprint on April 29. Zamora noticed the rock looked like it had been struck by a leg of the UFO. Stanford, realizing the importance of the traces, removed the rock and transported it to NICAP for analysis.25

Stanford didn’t respond to the information for more than a decade. It was with the publication of Socorro “Saucer” in a Pentagon Pantry that Stanford let his thoughts be known. He told the story of his journey from the landing site in Socorro and the recovery of what might have been important physical evidence to the loss of that evidence because of Richard Hall and NICAP. Stanford hadn’t wanted to use Goddard but Hall led him there.

Hall responded to Stanford’s book and the allegations about Frankel with a scathing review in the MUFON UFO Journal . He wrote, in part:

In a nutshell, I consider Stanford’s account of NICAP’s part in the Socorro investigation—and particularly his unfounded claims of a secret, positive analysis report on the alleged “metal scrapings of the rock”—to be both highly distorted and a highly subjective version of what transpired....26

Neither Dr. Frankel nor anyone else at NASA ever suggested to me that they were leaning toward an extraterrestrial interpretation. In fact, when Dr. Frankel talked to me about tentative findings of a zinc-iron alloy, he said to me that the results suggested a zinc pail....

His [meaning Stanford’s] entire case rests on two apparently undocumented and unverifiable phone calls that only he can witness. In addition, no one else involved in the Socorro investigation remembers the startling [and presumably unforgettable] positive NASA analysis report that only Stanford remembers.27

Stanford’s response was also published in the pages of the MUFON UFO Journal as well as his book on the Socorro landing. He pointed out that he had explained, in his book, how the conversations had taken place. He reacted strongly to Hall’s somewhat-guarded suggestion that Stanford had not been completely candid in his descriptions of the search for the lab to analyze the fragments and then once position results.

What was overlooked in the exchange was that alleged evidence was handled poorly; that alleged conversations could not be corroborated; that the information from NASA, based on their examination of the material, had a mundane answer; and that hyperbole was sometimes substituted for analysis. In the end, it was clear that even if the material from the rock had been from an alien spacecraft, there was nothing in the analysis to prove that. The materials were not exotic and they didn’t vary from those found on Earth.

There was one point that Stanford made, and it was about the melted sand, the vitrified material that was allegedly recovered. Here, Stanford acknowledges that the source of the McDonald letter was Hall and that should have been noted in the book.

The squabble continued to the point where Hall had said that Stanford had selected the NASA lab and Stanford saying that it was Hall who pushed it on him. In the end, nothing was resolved, and those on the outside could only regret that possible physical evidence that might have answered some of the questions had been lost.