CHAPTER 2

Vampires Everywhere!

Bram Stoker probably had heard of earlier vampire tales when he was a young boy. The idea that some people die but can still walk the earth has been part of myths and folktales for centuries. These people are often called the undead.

The undead include creatures such as zombies, ghosts, mummies, and vampires. An evil spirt of some kind keeps them from dying completely and drives them to harm the living. What sets vampires apart from other undead is their need for blood from a living person.

Blood-sucking undead creatures of early folktales included the jiangshi of China. They walked with stiff arms and usually had greenish skin. In parts of what are now the African nations of Ghana and Togo, some people told tales of the Adze, a spirit that could take the form of an insect and then bite its victims, which were often young children.

Starting about five hundred years ago in parts of Europe, people talked about vampires. They believed there were many ways to become one. Some thought that people who drowned might never really die, that they could instead remain “undead.” Others believed that if a cat, dog, or living person walked over a new grave, the person buried there might become a vampire.

Jiangshi

In some European legends, vampires were said to be thin, with scabs covering their bodies. Their skin was deathly pale—until they drank the blood they needed so badly. Since vampires were not truly dead, their hair and nails continued to grow. The tales also said that vampires were incredibly strong and could change into the shape of other animals, such as wolves. A vampire was strongest at night, and some stories said sunlight would actually kill one. In some countries, though, people believed vampires could go out during the day, but they lost their superhuman powers in daylight.

People also talked about how to keep vampires away. The strong smell of garlic was thought to work, and people were told to spread it around windows and doors. A cross, or even just the sign of a cross, was also said to turn away vampires. Vampire tales also discussed how to make these undead creatures really dead, once and for all. The methods included cutting off the vampire’s head or driving a sharp wooden stake through its heart. A shot through the heart with a silver bullet blessed by a priest could also do the job.

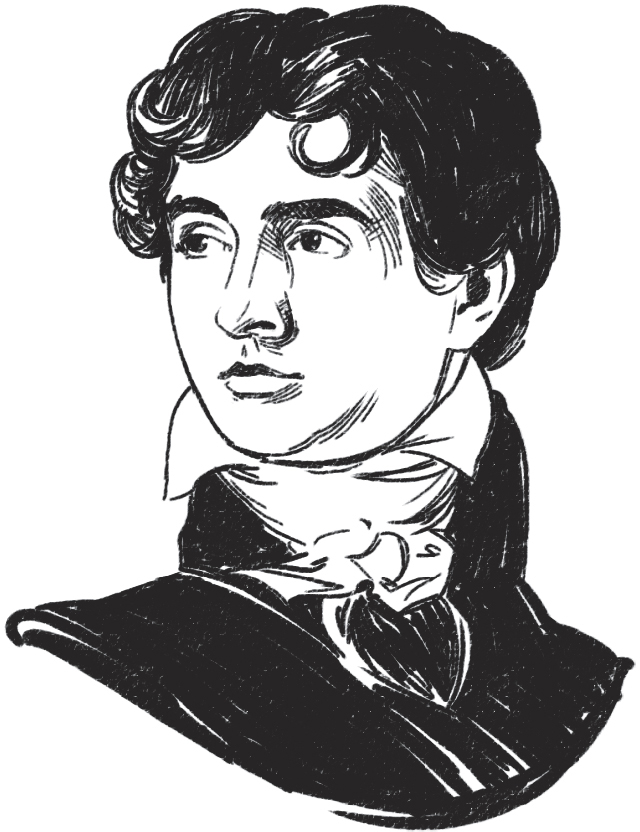

John Polidori

Starting in the 1800s, some writers in England began including vampires in their poetry. But the first full-length story about one in English is thought to be The Vampyre, by John Polidori. It was published in a magazine in 1819. The vampire’s name is Lord Ruthven, and Polidori wrote he had “dead grey” eyes and pale skin.

Several decades passed before another popular vampire story was written in English. Varney the Vampire, or, The Feast of Blood by James Malcolm Rymer was published in London in 1847. The novel had first appeared as more than two hundred chapters that were published separately as booklets. These short tales were known as penny dreadfuls because they cost just a penny and often told tales of bloody horror.

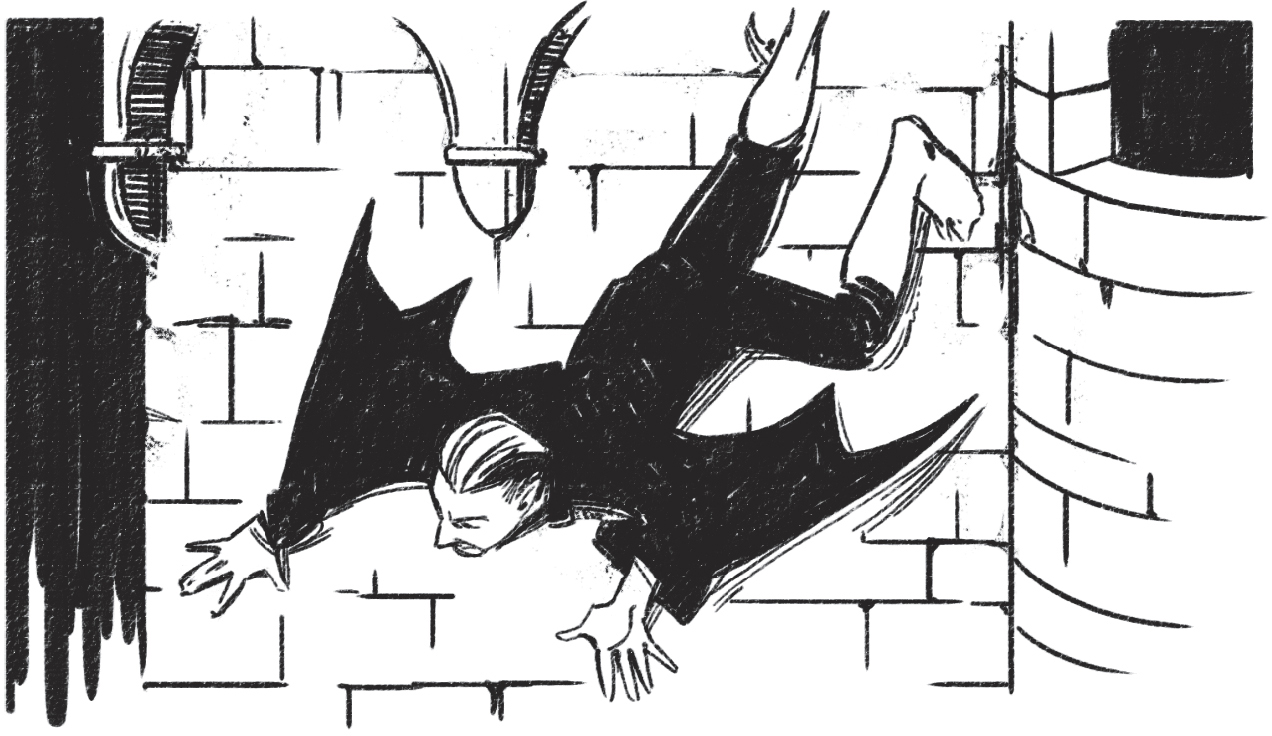

In this story, Varney travels from central Europe to England and begins seeking out young victims. He climbs into their rooms at night while they sleep. Varney has fangs that leave two bite marks on his victims’ necks. And he can climb down stone walls.

Many animals have been associated with vampires, but the most famous is the bat. A few hundred years before Bram Stoker was even born, Spanish explorers had seen bats in Mexico and South and Central America that they believed drank the blood of other animals. The Spaniards knew the tales about human vampires, and they called the bats they saw vampire bats. Bram had read about vampire bats. He may have also heard older tales that linked vampires and bats, and became the first writer to tell a story about a vampire who turns into one.

As for vampire bats—they don’t actually suck their victims’ blood. Instead, they cut an animal’s skin with their teeth, then lick up the blood as it oozes out. But they can’t go too long without it, just like the vampire characters in folktales.