part one

The Wand and the Wizard

You ask deep questions,

Mr. Potter. Wandlore is a complex and mysterious branch of magic.

Mr. Ollivander in

Mr. Ollivander in

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J. K. Rowling

The magic wand is the iconic instrument of the wizard. By “wizard” I mean mages of all kinds — witches, sorcerers, druids, and adepts of the mysteries. We all know them from fiction, films, and video games. If there is a fairy godmother or a sorcerer’s apprentice, we expect there must be a magic wand too. Sometimes wizards like Gandalf or Merlin appear with a walking staff, but this too is a wand, for the word simply means “a rod.” Size doesn’t matter. Real-life mages also use wands. In the East, Taoist wizards and Zen masters convey their power through staves. The druids of old Irish myth and legend wielded wands to conjure magical fogs, to transform adversaries (or themselves) into pigs, to foresee the future, or to recover lost information.

The druids were the wizards of the ancient Celts. Today’s druids also employ wands in their ritual work, healing, and meditations. Ceremonial mages have revived the ancient mysteries and employ many types of wands in their lodges. While magic and wizards were driven underground in Western culture in the Age of Enlightenment (the 1700s), these old traditions continued to be revived; in the past three hundred years, druidry, witchcraft, and hermeticism have become once again living and growing spiritual traditions. They all share an understanding of the visionary imagination and the many spiritual dimensions of existence. They also all share the use of wands to perform magic. In druidry today, the wand symbolizes individual spiritual inspiration, the awen of the bards. Awen is a Welsh word meaning “poetic inspiration,” but it is also a living force, a transformative energy directed by the will of the enchanter.

Across many cultures and historical epochs, the wand has been an instrument for conveying a mage’s will. At its simplest, the wand is a branch, more or less straight, used for pointing and directing the intentions of the mage outward into the world of manifestation. Some wands are made of metal and crystal, bone, or even clay, and some ceremonial magic traditions, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, use several quite elaborate wands for specific purposes, offices, or rituals. However, it is the simple stick from which magic wands developed. For the druids, each type of tree had special powers, and druids today are beginning to reclaim the ancient understanding of the tree spirits, or dryads.

The twentieth-century Czech magus Franz Bardon wrote of the symbolic nature of wands and the ability of the wizard to apply them to different purposes. A wand is always first an instrument of will, that power through which a wizard influences the higher spheres. Different wands may be dedicated to particular purposes: one to influence other people, animals, plants, and objects; another to cure people suffering from diseases or other misfortunes; and perhaps another to evoke spirits, intelligences, or daemons (Bardon, The Practice of Magical Evocation, 41).

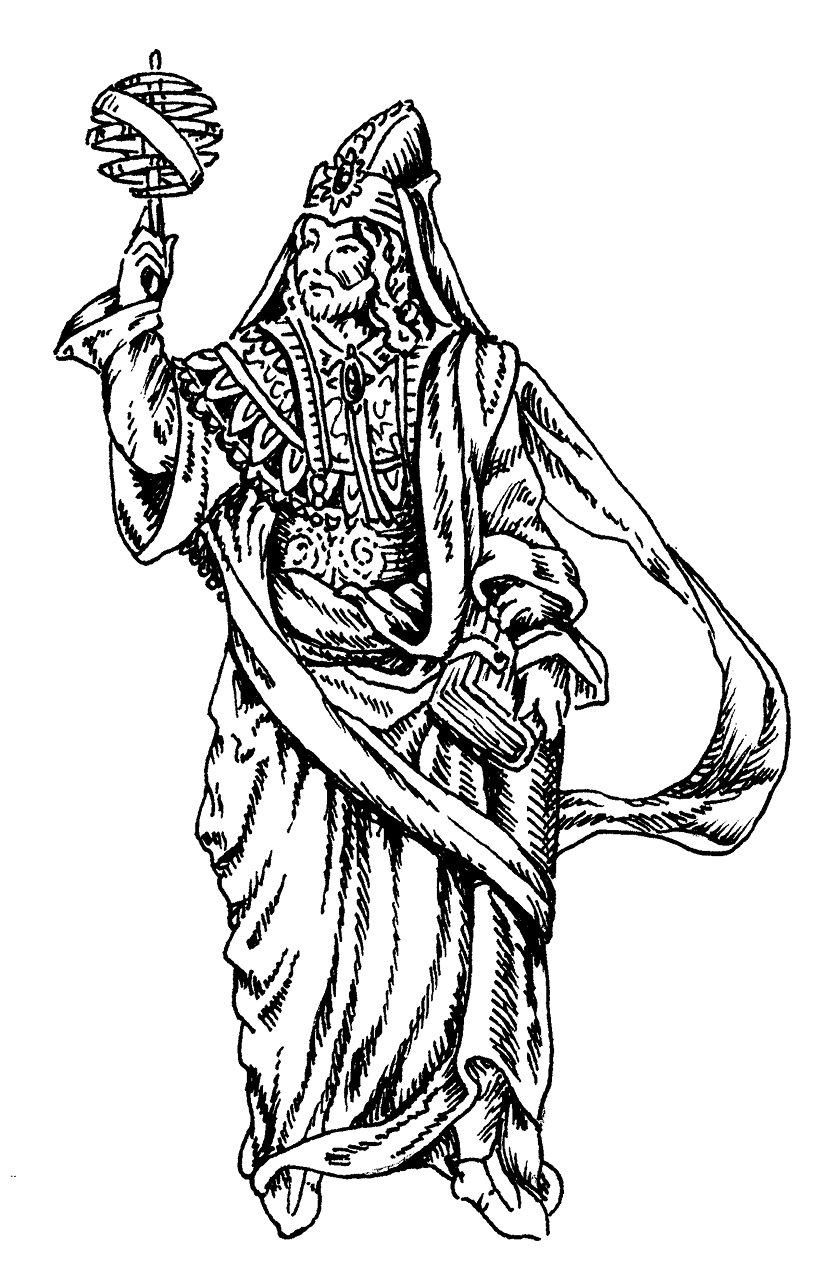

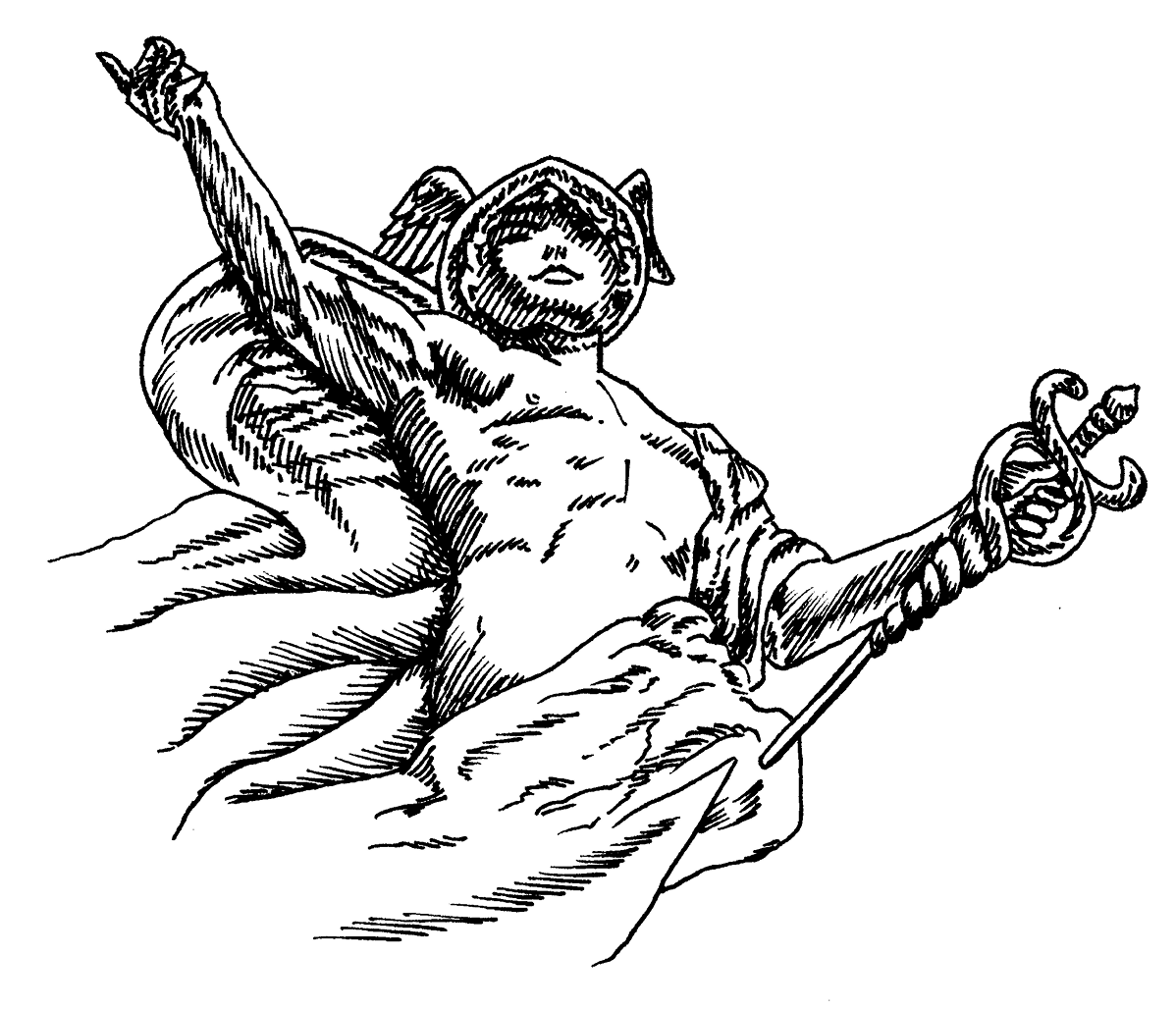

In the Greek pantheon, Mercury (right) was Hermes, the messenger of the gods and wielder of a magic wand; he evolved into the figure of Hermes Trismegistus (above), the “thrice-great” Hermes who is the legendary founder of the Hermetic magical tradition.

Wands direct the will outward from the mage into the world. The upright staff of the itinerant sage, by contrast, draws power from the earth and the sky with the staff and the wizard as the conduit. A small wand has the virtue of being easily concealed. The staff is usefully concealed in having practical value as a walking stick. A rod may be used for herding animals, and it is also the traveler’s most practical weapon. Buddhist monks have used a staff with jingling metal rings on the bronze headpiece to announce their arrival in a village and to warn small creatures out of the way lest they be inadvertently stepped on. Taoist wizards use staves as a martial arts weapon and as a walking stick. The staff is an archetypal symbol of the wise old wanderer full of hidden powers. Nowadays, in Western cities, it would be pretty eccentric to walk with a staff, but it is still a good tool for the open road and wilderness track, and many druids today adopt them as part of their ritual accoutrements. Wands, by contrast, are mostly used in private ceremonies and spell weaving.

Did the wand derive from the wizard’s staff, or vice versa, or did each evolve independently from a common source in the royal scepter? At its most primal level, the magic wand, along with the club, is derived from the mystery of the male phallus, a symbol of life and generativity but also a symbol of self-assertion and will. A royal scepter or a marshal’s baton symbolizes the authority to command or lead others. One can easily see the mage’s wand and its purpose at any orchestra concert in the conductor and his or her baton.

Joe Lantiere, in his lavishly illustrated history of “mystical rods of power,” traces many details of the magic wand and its relatives. He mentions the talking sticks, dance sticks, rain sticks, and rattles of the shamans and tribal medicine men. There is also the caduceus of Hermes, messenger of the Greek gods and a patron of magic, and the staff of Asklepios, each twined with snakes. Mr. Lantiere notes the connection between the serpent-twined staff, or wand, and the human spinal cord with its coiled “kundalini serpent energy.” He cites Manly Hall when saying, “The staff is symbolical of the spinal column of man, and this is the true wand of the magicians; for it is through the power within this column that miracles are performed” (Lantiere, The Magician’s Wand, 43).

Similarly, W. Y. Evans-Wentz describes the silver branch of the bards and its link to the world of Faerie, that realm of the otherworlds replete with magical power:

Manannan of the Tuatha Dé Danann, as a god-messenger from the invisible realm bearing the apple-branch of silver is, in externals though not in other ways, like Hermes, the god-messenger from the spiritual realm of the gods bearing his wand of two intertwined serpents. In modern fairy-lore this divine branch or wand is the magic wand of fairies; or where messengers like old men guide mortals to an underworld it is a staff or cane with which they strike the rock hiding the secret entrance (Evans-Wentz, The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries, 343).

Joseph Peterson, in his web article “The Magic Wand,” speculates that one origin of magic wands may have been the ceremonial bundle of twigs carried by Persian Zoroastrian priests (the original “magi”). This bundle is called a baresman, or barsom. It was traditionally made of tamarisk twigs and functioned as a bridge of souls between the realm of mortal life and the realm of the spirits. It was a conduit of power and communication from spirits to human beings. Admitting no scholarly authority on ancient Persia, I would note on the face of it that the bundle of twigs and the name barsom is remarkably similar to the witch’s besom, or broom. Was the witch’s broom descended from this Eastern fire cultus, the combination of a wizard’s staff and the magus’s sacred bundle of twigs?

Peterson also notes that the Roman flamen, also a priest of fire, used similar bundles of twigs, and this is even more likely to be a direct borrowing from Zoroastrian practice. Hans Dieter Betz has included in his collection The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation a spell to summon a familiar spirit in which, at one point, the mage shakes a branch of myrtle to salute the goddess Selene (Betz, 5). This branch would appear to be one with leaves still on it. In another operation (to summon a spirit of prophecy), we find twigs of laurel used: “Take twelve laurel twigs; make a garland of seven sprigs, and bind the remaining five together and hold them in your right hand while you pray” (ibid., 13). The laurel branches have leaves on them and the leaves are inscribed with special magical ink. So, the practices are not quite like the more modern use of wands, yet we may say the magical papyri provide us with documentary evidence that wizards in the Hellenistic Age used the magical properties of branches taken from particular trees. Myrtle is considered to be sacred to the goddess Selene; laurel to Apollo.

We find other wands in myths that are sources for our modern wands. One wand user, the Greek god Hermes (Roman Mercury), has long been linked to the passage between earth and the higher realms. The staff or rod of Hermes has become associated with the caduceus, a baton entwined with two snakes mating. Originally, the Latin word caduceus came from Greek kerykeion, from keryx, a herald. The term kerykeion skeptron, meaning “herald’s wand,” was abbreviated to kerykeion and then in Latin became caduceus (Friedlander, The Golden Wand of Medicine, 5). Greek skeptron is the root of our English word scepter. The caduceus of Mercury-Hermes has come to be associated with healing and the medical profession due to its similarity to the rod topped with a brazen serpent employed in the Bible by Moses to work healing magic. It has also been mixed up with the wand of Asklepios, a Greek demigod closely associated with medicine and healing. Asklepios used a wand that is usually depicted as a rough branch with a single snake spiraling around it (ibid., 6).

The association of Mercury and wands shows the wand used not for healing but for magic. Herald of the gods, Hermes-Mercury is lord of communication; magic is, after all, a form of communication. We even call an act of magic a spell, which is the Old English word for “word” as in gospel (“good word”) or the verb spelling. To cast a spell is to cast forth a word or series of words. But the significance of the ophidian wand — the wand with snakes — bears a closer look.

An example of a serpentine wand, this one

with a crystal tip and a pommel stone.

Serpents are powerful symbolic animals in virtually every culture. The serpent symbolizes the fire of life and the will to live. Their resemblance to the phallus makes them ripe to being viewed as fertility symbols; their ability to shed their skin makes them the ideal animal symbol for immortality. When one dies, one “sheds the skin” of the body, and the serpent does just that yet lives on. So, it should be no surprise that the snake symbolizes healing, but it clearly also symbolizes knowledge and wisdom — the knowledge of immortality at the very least, which has always been itself emblematical of all knowledge. Witness the serpent in the Garden of Eden, the original educator and initiator.

But what is the significance of two serpents intertwined? One answer is that the twin snakes represent twin helical energies bound together; this might be interpreted today as the double helix of DNA. It can also be interpreted to mean the energies of yin and yang or the forces of order and chaos, creativity and destruction, light and dark — or all of the above. Friedlander tells us:

According to mythology, Hermes threw his magic wand between two fighting snakes. They stopped their fighting and entwined his wand. Some have interpreted the entwined snakes as copulating, so Hermes was considered to have brought love out of hostility (ibid., 16).

The symbol of two entwined snakes resembles the figure eight, the emblem of infinity. The forces indicated by the figure eight are indeed infinite as well as eternal. It is no coincidence that the kundalini energy — that life force that the yogis describe as running up one’s spinal column — is also symbolized as a serpent. The serpent lies coiled and still, then rises up and strikes. The snake’s behavior is a good metaphor for the action of building up magical potential and then releasing it with the triggering incantation or gesture, all of which points us to the essence of magic and the wand itself — the will.

The most basic hidden secret of magic is that the wizard must go within him- or herself, inside the mind, and there, encountering Hermes, lord of communication, be led into the otherworlds. These otherworlds, as they are often called in Celtic legends, are the higher planes of our existence, especially the astral plane and the mental plane. If Hermes, the divine psychopomp, leads us to those worlds, then our consciousness becomes capable of magical action.

The caduceus

The power we call the will (Latin voluntas) is the direction of one’s intentions to manifest changes in the higher planes and so bring about change in the material world; this power to transform matter is the essence of elemental fire. In the system of magical elements, fire comprises all energy and, by extension, what scientists call electromagnetic energy, thermal energy, and force fields of various kinds, as well as emanations of spirit, desire, passionate attraction (or repulsion), love, anger, aggression, and devotion. These things, which psychologists call emotions, may be considered in a magical view of the world to be palpable forces projected outward from one’s astral being. It is this quality of extension that is evoked in the linear shape of the wand.

If the wizard’s staff is like the spinal column linking heaven and earth. A wand is the pointing finger of a child, the thrusting phallus, the beat of the maestro’s baton, the command of the king’s scepter, the pushing up of the new green shoot, the index finger that signifies the number one: single-mindedness and directed intention. The wand, staff of office, marshal’s baton, and so forth, are all instruments of profound transformation, symbols that transform their bearer into a person of authority and will.

In the Western magical tradition, fire is one of four elements, the building blocks of the cosmos. These are not the elements of the periodic table used by chemists; they are the four essences identified by ancient natural philosophers and medieval alchemists. They are organizing forces underlying the material world, not matter itself. However, the four alchemical elements are manifest in the physical states of matter; that is, solid (earth), liquid (water), gas (air), and plasma (fire). But each has many more manifestations on the higher planes.

Elemental fire, we may say, is life itself, and wood embodies this conceptual fire because it comes from a living being. That is one reason a wizard’s wand is most often made of wood. This is especially notable in the druid tradition, in which druid wands are usually described in terms of particular sacred trees: a wand of ash, birch, hazel, or oak. The old druids performed the wonders of transformation by borrowing the power of the trees, and those following the druid path today still do. The method is somewhat similar to the medieval Kabbalist or Solomonic mage borrowing the powers of daemons; however, there is a significant qualitative difference.

Medieval magi worked with a theory that daemons and the dead could be commanded by means of the names of God; their reasoning being that the damned were under complete control of the Creator and so did not have free will of their own if the divine names were used. Druids operate in a completely different cosmology. There are no damned spirits, though there are mischievous creatures and many divinities. Trees, like all other living creatures, are free within their natures, so the druid mage does not command them with god names. For druids, the spirit of a tree is one of the many kinds of spirits that animate the worlds. They are part of an ecology of spirit, as we might say, in which one species is not more important than another, but all are valued equally, and the soul — or individual consciousness — may manifest in different forms within different lifetimes. Nor are rocks and minerals excluded from the many species of spirit entity. Different species are animate or intelligent in differing ways, but spirit is continuous throughout the cosmos.

The ubiquity of spirit in nature means that the material and the spiritual are not radically separate. The magical properties of trees and their wood are practical — just as practical as the material properties of wood considered by the carpenter or builder. Both kinds of properties are an intrinsic part of the tree for those with the eyes of ethereal perception open. A bridge-builder does not need to command alder wood to resist rot when submerged in water, nor does a wizard need to command a wand of alder to aid in seership and oracular crossings between worlds; it’s just the right wood for the job. What spiritual affinity must be created between wizard and wand is done not through a hierarchy of spiritual authority but through the affinity of kinship and love, and through an understanding of the material and spiritual elements. It is a relationship of willed co-creation, not authority and service.

Within magic, four elements compose material existence. These four are air, fire, water, and earth. A fifth element, aether, is also included in the system, but this quintessence is, in fact, of a different order altogether. Quintessence is that spiritual substance from which air, fire, water, and earth are made. The four elements are symbolized by an equal-armed cross within a circle, or by a square. The four plus one that is the great mystery is symbolized by the pentagram with its five points.

Each element manifests in five different planes of existence, what we might call five dimensions of one reality. Those planes are sometimes called worlds because they are inhabited by living entities. The planes are commonly named material, astral, mental, archetypal, and divine. The part of reality that we perceive with our ordinary physical senses is the material plane of existence, but we also exist in and can learn to sense the other planes. The classic work on this subject was written by Theosophist and Freemason C. W. Leadbeater and titled Man Visible and Invisible. Each of us exists simultaneously in all four worlds, even if we are unaware of it. You can think of them as dimensions of one reality. Understanding this magical cosmology underlies all magical work, including the art of wandmaking.

The element of fire is where we will begin, and it manifests in the astral world as intention, will, desire, and action. Wandmaking is itself an act of intention and will. As such, it involves both the fiery principles of creation and extension and the watery principles of destruction, restriction, and flow. The creation of a wand in wood involves removing some of the material used and altering it by the exercise of restriction into the desired shape and material configuration. Moreover, the magical creation of a wand involves the expression of the wandmaker’s emotions, or his or her feelings, through the material medium, and this too combines water and fire — the force that draws heart to heart and the force that gives the union movement and purpose. It creates a material (earth) embodiment of ideas (air), will (fire), and relationship (water). The caressing hands of the maker imbue the wand with magical power and awaken the sleeping dryad spirit in the wood (aether or spirit). The act of crafting a wand is, like most magic, fundamentally an act of love and passion applied to the higher dimensions of the physical implement.

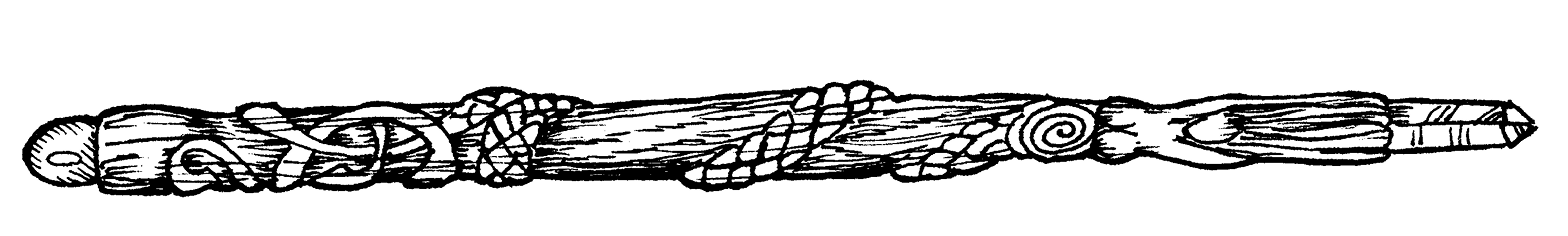

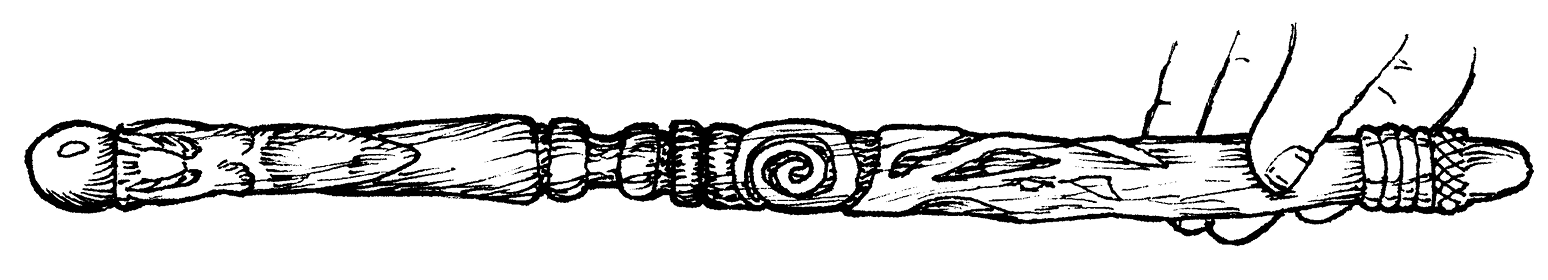

A wand may be simple and elegant, knobbly and overtly branchlike, or it may be elaborately carved with sigils, runes, and totem animals. But at bottom it is the wood itself and the wandmaker’s mindfulness that must give it the qualities that prepare it to be taken up by its owner and used as a magical instrument. The wakening and drawing forth of the tree’s spirit, or dryad, occurs not only in the final act of enchanting the wand but throughout the process of its making as the wandmaker pours into it his or her own spirit.

Some among the cognoscenti say that a druid or witch must make his or her own wand. Some suggest that the use of iron tools of any sort detracts from the wand’s energy, so a flint should be employed to better connect us to the Stone Age past. Such rules can certainly be followed for those who accept their premises. While steel tools naturally give many trees the willies because they are so often mutilated and killed by humans wielding such implements, I do not believe there is anything inherently detrimental in steel or iron. Indeed, iron is one of the magical alchemical metals sacred to Mars. Metallurgy is an art that lies at the root of magic and alchemy. It was practiced by the ancient Celts and the Tuatha Dé Danann to a very high degree of refinement.1 A sharpened steel blade is a truly magical thing.

There is no doubt that the use of one’s own hands in quiet contemplation at a slow, human pace brings a deeper communication with the spirit of the wood and allows love and attention to be lavished upon it with hand tools and ancient craft. The object for the wandmaker should never be to “save labor” or to produce a wand quickly. One should feel free and unrushed, and let the moon turn through her phases as the work proceeds.

Nothing embodies elemental fire better than the tree striving upward in the dense forest, triumphing over its crowding neighbors to dominate the canopy and aspire to the light — all the while being home and food to many animals, birds, and insects. Thus, it is to the tree spirits that we must turn to see inside the workings of a magic wand.

The dryad is the spirit of the tree — its essential pattern, or psyche. It is a living being linked to the tree and growing with it, but it is also a transtemporal and transspatial creature, living in the astral dimension as much as in the material world. This is the same way I would describe the human soul or the spirit of any living being. Commonly, spirits are thought to be some sort of substance that inhabits a physical body and leaves it on the moment of death. Neither of these statements is quite accurate, as I see it. The spirit does not live in a body like a person lives in a house; it emanates the body, which is to say that the spirit is causally connected to the body and able to exist without it.

Moreover, death does not completely separate the spirit from its emanation in matter any more than life confines the spirit to the body. In the case of humans, we note that consciousness is gone, but in many traditional cultures it is understood that the spirit lingers for some time. This is even more the case with trees because their bodies decay so slowly and because their consciousness is so much more diffuse than that of a spirit in human form, where indeed very slight disruptions in the delicate chemistry of the brain can wreak havoc on the psyche.

So, generally speaking, when a branch falls off a tree or is pruned, the dryad spirit is still in the wood. It is not really accurate to speak of “parts” of a spirit, but one might consider the spirit of the wand to be part of the tree’s psyche. If a part of the physical tree breaks off, the spirit in that part remains and is like a piece of broken holograph in which the whole picture will be in each fragment. So, the dryad does not so much divide as it is reproduced in miniature when the break occurs. The spirit always remains to some degree until after the wood decays, but it may be asleep. In a sound branch, the spirit can be awakened by enchantment when the branch is crafted into a wand.

In some types of tree — oak and ebony come particularly to mind — there is a clear presence and consciousness in the wood that interacts with the wandmaker from the very start of the work. Such consciousness will often cause a branch to be cast in one’s path and call out quite unmistakably to one who is aware. Other trees are much more shy, and their spirits may be hard to wake up in the enchantment process.

Orthodox modern botanists do not accord consciousness to trees.2 Yet, among the Fay and many modern druids, trees are considered to have spirit, mind, and consciousness, as well as will and emotions (all of which are collected in the word psyche). Trees have a larger proportion of feeling and intuition than intellect in their psyches (to use our human terms). They do not reason the way we do, but they do ponder, brood, and feel. If a druid (or other magical person) touches them and makes contact with their dryad spirit, some trees at first seem sluggish and hard to reach. Other trees respond immediately to such attention with the same kind of reaction many of us would have if suddenly touched by the mind or gentle hand of another being. Some seem surprised, and who can blame them when for hundreds of years the touch of a human hand has most often been a prelude to violent death? Fortunately for us, trees have a very long and deep race-memory that goes back to before humans became so numerous and so destructive. Trees do not hold human emotions like hatred or revenge or even fear, though they can register pain and distress or anxiety.

It is somewhat misleading to anthropomorphize dryads. They share many spiritual (and, for that matter, biological) qualities with us, but they do not think or live like human beings. In its present incarnation, a tree is fixed in one place, its mobility limited to the dance of leaves and the relentless reaching of root and branch. It has an intimate relationship with the elements that we can hardly imagine — especially to the wind and sun. Much of a tree’s attention is directed into the ground through its roots and outward into the air through its branches and leaves. Deciduous trees drop their leaves and grow new ones; many drop seeds or flowers. They carry on both symbiotic and hostile relationships to insects, mammals, and birds. They are physically intertwined above and below with their neighbors, especially in a forest, where one often gets the sense of one vast being rather than a collection of individuals.

There is a great deal of activity in trees but it is the sort that, in humans, remains largely unconscious. We too produce seeds and eggs, grow hair and nails and new skin, circulate our sap, and throughout childhood our whole body is growing. Even in adulthood the body changes shape, and our skin is replaced every seven years. But trees have very different bodies, and their spirits are diffused throughout their bodies without the distracting, narrow focus of a brain structured by language. They do not even have a nervous system. Thus trees, unlike humans, have never suffered from the dichotomy of mind and body, yet they can sense, feel, and communicate.

If a tree’s consciousness focuses on different parts of its body, it is on the roots, the trunk, and the branches in seasonal cycles of growth and withdrawal. The leaves are the most sensitive organs of trees, but the bark is also very sensitive, flowing with tree-blood underneath, much like our skin. It is perhaps significant, however, that a tree’s “skin” is not sloughed off and renewed like ours, but quite the opposite: it grows thick, hard, and cracked, like a protective shell. Even in such species as the paper birch, whose tissue-thin white bark is peeled by humans to make baskets and canoes, there is quite a different quality to this “skin.” It is not quite the sensitive and supple organ we humans enjoy but is still a medium of sensation.

I associate many of the trees and their wood with one of the four elements (earth, air, fire, water). Some of the old Celtic and English treelore also makes such associations. Alder, for example, is considered a watery tree, in part because of its ability to be immersed in water without rotting. Willow is likewise considered watery because it so often grows near water. Moreover, willow is associated with the moon, which itself is linked to elemental water because of its influence over the seas and women’s menstrual cycles. Oak is associated in many traditions with the sun and with lightning. The associations of trees with elements and deities are drawn from many sources, including my own intuition. You can make your own judgment based upon individual experience quite as well as I have done, and you will find that other wizards will differ in their associations. The matter of associations between trees and constellations or planets will benefit from more organized research as modern wizardry continues to mature.

It is important to note that while many trees can be found to have sympathies with the philosophical elements, dryads themselves are not “elemental spirits” as such. Elementals, as they are usually called, are beings that embody one of the four elements. Their traditional names are salamanders (for fire), nymphs (for water), gnomes (for earth), and sylphs (for air). Dryads, by contrast, embody the “fifth element” recognized in the Taoist system of elements: wood. Dryads are representative of all of the four elements combined into a quintessence that is a living organism.

Trees draw water and minerals from the earth, and light from the fire of the sun; they breathe the air and exhale oxygen, which is the chemical medium of terrestrial fire. Moreover, their dried bodies are the chief fuel for human fires, and as charcoal they hold the secret for smelting metals and forging steel. As ash or decayed wood, trees become the earth element in soil. Trees are the pinnacle of the plant kingdom, filled with nobility, grandeur, and wisdom that comes from a long life in one place. We are indebted to them in ways that are often not realized. In the gift of oxygen, wood, and paper, trees have made human civilization possible. They are thus, we may say, the midwives of all intelligent life and human creativity.

So, what about druids then? I am a druid, so I write from that standpoint. Many books have been published on druidry over the past twenty years, but still it may be necessary to address the question of what a druid is. Druids are not, of course, dryads, even though some etymologists note the similarity between these words derived from Gaulish and Greek, respectively. Druids are notoriously difficult to define. Ask four druids for a definition, and you will get five different answers. Here’s mine: a druid is a wizard, a wise one, in the Celtic tradition. Druid wisdom is rooted in the clear, conscious apprehension of all the elements in one’s being and in the close attention to nature. For a druid, deity is immanent in the natural world.

The term druid has been linked with two other distinct classes of mage in the Celtic traditions: the ovate, who is a healer and seer, and the bard, who is a lore-master, poet, and enchanter. In many druid organizations today, ovates and bards are considered to be druids, even though the highest grade of the order are called “druids” as a title. In reality, apart from organized orders, anyone who feels called to the druid path may call him- or herself a druid. Moreover, there is nothing preventing today’s druids from studying Hermeticism, Kabbalah, witchcraft, or ceremonial magic. Throughout this book, I use the terms druid, mage, witch, and wizard interchangeably, without reference to any particular religious point of view.

A druid begins magical training by becoming deeply aware of the four elements, and then, as an ovate, cultivating the fifth element. This study leads finally to an integration of all five elements into a transcendent being that comprehends spirit, the living combination of all five elements into a conscious structure. The druid’s sentience goes beyond the merely physical, emotional, or intellectual so that the ego-consciousness becomes a tool, not a limitation, and the whole self is aware of all its parts working together in the subtle dance of existence. This level of self-awareness is beyond that of most human beings. It is very like the awareness of the trees.

However, dryads lack one thing the druid has, which is language. Human language is unique to humans. Other sapient beings — such as elves, dwarves, giants, and the many other denizens of Faerie — share this power of language, and to a degree are both limited by it and can use it transcendently. If the ego, as the center of consciousness, does not transcend language, it is limited to those thoughts that can be expressed in the languages it knows. There are few languages, even in Faerie, that can express the plenitude of spiritual being. But all language arises from the use of symbols, and that is another fundamental aspect of magic.

In the practice of wandmaking, one would do well to first seek out this state of being, this higher sentience of the mage. It is the first necessary step to conscious communication with dryads, as well as the first step to enchantment.

A fancy wand with goddess handle, carved acorn point, and what I call a “flame tree” in the middle.

Modern druids, imagining how their ancient forebears may have felt in their sacred groves, work to develop a special rapport with the dryads, or tree spirits. One way to do this is to meditate with one’s back up against the trunk of a tree. Seated or standing, enter into a meditative state and listen. The only way to hear a tree communicate with you is to listen with your whole being. Your ears don’t have any more to do with it than your liver.

“Becoming the Tree” Meditation3

- Let go of any expectations.

- Feel your deep breathing; slow it down.

- Wave away the chatter of your mind as you might wave away an annoying fly.

- Imagine that you are the tree.

- Imagine that your spinal column is the trunk of the tree.

- Imagine that your legs and feet are its roots, extending deep into the moist, dark soil.

- Your head becomes the crown of the tree and your eyes, its many leaves.

- See through these leaves, not through your limited eyes.

- Your awareness extends in all directions equally.

- You no longer have a “face” or a “back,” and your attention is raised up to the sun and the air, downward to the soil and water.

- Spend some time feeling what it is to be the tree. Then listen for what the tree may tell you.

- If you feel moved to do so, ask the tree a question or express your feelings for it.

- Words may form in your mind out of what the tree communicates. If not, don’t worry; be aware of feelings, emotions, or symbols that may occur within your mind.

- When the time feels right to return to your own body, feel your tree-consciousness recede and your human mind return to its body, its orientation, its skin and bones.

- Open your eyes, and focus on your breathing for a time.

- Touch the ground around you to re-establish yourself firmly back in your ordinary awareness. You will retain the memory of what your heart has learned.

- Whether or not you feel that the communication was successful, thank the tree for its blessings and its presence. Honor it and leave a small gift in the soil at its base — a bit of tobacco or other sacred herb, a pebble, a coin, or some water thoughtfully given.

- Pay attention to your dreams after this encounter.

- Write down what you experienced — perhaps as a poem, a song, or an image, symbol, or drawing, or express it in music or paint.

Cultivate a new attitude toward trees. In our modern mechanized culture in the West, we too often walk past the trees around us without even noticing. To the city dweller, trees may be merely a kind of decoration or, at best, a source of shade adding value to one’s property. To the farmer, the trees may be windbreaks or timber lots, appearing in the imagination only as so many dollars of income when they are mature enough to cut into lumber. In a culture of clear-cutting forests that all too often assumes nature to be nothing more than “natural resources,” we lose the love of trees as they are, inspirational through beauty, not reason.

If you desire to follow the druid way or that of any other nature religion, if your hope is to converse with dryads, you must first of all tend to your attitudes, your consciousness, and your awareness at the deepest level. You will have to cast off programming that has been poured into your head all your life from preachers, teachers, television, radio, and movies. All of these cultural institutions replay the same messages: humans are privileged, humans are chosen, nature is something to manipulate and “improve” — something to conquer. Animals, trees, much less the grass and the weeds and the bacteria in your own gut, are regarded as mere objects of study and scientific tinkering, not as noble and autonomous beings, as our benefactors and ancestors. “Machines are the true source of glory and self-esteem,” say all the television commercials. In today’s Western culture, technology and chemistry are still preached as the way to salvation, the way to paradise. Yet public attitudes have changed much in the past hundred years. If you are drawn to the druid way, chances are you already love trees and the wild.

Having first become druid-wise, what does the wandmaker need to do next in order to pursue the art of making magical instruments of wood? First, greet the trees around you. Touch the delicate leaves of the saplings. Lay a hand on the rough bark of the old ones, and offer them your respect, love, and humility. The ancient Greeks, who invented the name dryad (and also hamadryad ) for tree spirits, must have known a thing or two about the trees in their early, more shamanic days. By the classical era, when dryads were depicted as elusive female spirits, the picture seems to have been filtered through an anthropomorphic literary imagination that was no longer quite in touch with the more-than-human world on its own terms.

Yet the gesture of anthropomorphism is a way to acknowledge that tree spirits are the equals of spirits in human form. The dryad moves the earth and breaks boulders; it offers up its branchings to the nests of eagle, raven, and wren; it bears with gentle patience the depredations of squirrels and beetles, knowing that the body is the manifestation of life and food for the next generation. The druid must cultivate a dryad wisdom, honoring the body for what it is, neither romanticizing it nor deriding it as a source of sin. We eat; we are eaten. We take; we give abundantly from the source of our life. Spirit goes on, leaving the body as a gift to the worms, the insects, and the soil.

Before all else, a wandmaker must love the trees. If a wandmaker has no personal connection and affinity with the trees and their dryad spirits, then he or she is still caught up in the web of Western modernity and its objectification of everything nonhuman. Making wands is not like making furniture legs or wheel spokes. Magic wands are not merely utilitarian objects that use the physical properties of the wood for strength, elasticity, or durability; nor should they be merely pretty theatrical props. Magic wands are more like offspring.

Woodworkers in general often do have much knowledge about the material properties of woods, and this kind of knowledge does come into wandmaking. In wandcraft, one does well to understand about the different grains of woods and the different stains and finishes that might be appropriate for cherry but not for oak. Linden is easier to carve than sinewy cedar. Yet such material concerns are only one layer of wandmaking as an art. So, let us turn to the first elemental aspect of wandmaking: fire and the spirits of the trees.

1 See Mircea Eliade, The Forge and the Crucible.

2 But for the contrary view, see Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird, The Secret Life of Plants (Harper and Row, 1973).

3 Though too long to quote here, I can recommend the tree meditations found on page 150 of Mellie Uyldert’s book The Psychic Garden. See also “Expanding the Sphere of Sensation to the Vegetable Kingdom” in Zalewski, 142.