INTRODUCTION

From the very inception of the firearm, one of the holy grails for manufacturers was to overcome the constraints imposed by the available technology and create a firearm that had the ability to fire repeatedly. The introduction of the perfected flintlock in the early 18th century did much to improve the reliability and efficient functioning of firearms, but loading and shooting were still tediously slow and much affected by wind and weather, which could blow priming powder from pans or soak the propellant. Gunmakers dreamed of being able to produce guns, both handguns and long-arms, that were able to be charged once and then repeatedly fired. Despite advances in manufacturing techniques, technological progress in the firearms industry was hampered by the only available propellant: gunpowder, a horrible chemical concoction incorporating all of the traits that were most undesirable in a propellant. It was dangerously volatile, usually when it wasn’t required to be, but was also hygroscopic (or water absorbing), making it extremely non-volatile, usually at the most inopportune moments. Furthermore, its slow burn rate resulted in relatively low velocities, and it produced a vast cloud of white smoke on firing. Even worse, it left behind a thick, sooty residue that choked gun barrels and touch holes and was highly corrosive if left uncleaned for more than a few hours. But it was all that was available, so for 500 years all firearms makers were forced to work within its confines.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries a few gunmakers very nearly achieved the impossible by producing revolving-cylinder pistols that relied on flintlock mechanisms. They were large, temperamental, expensive, and generally regarded as no more than novelties, but attempting to do the same with a long-arm was even more problematic. Using the revolving-cylinder system created too much weight and unacceptable loss of propellant gas from the gap between the cylinder and breech. Clearly, some form of breech-loading method was necessary, but this was a problem gunmakers had been wrestling with, mostly without success, for 200 years. Aside from the purely mechanical problems, much of the difficulty lay in the primitive cartridges in use. While paper-wrapped combustible ammunition worked tolerably well in a musket that was loaded and fired fairly quickly afterward, when used in a repeating arm, if the charge was left for any length of time, its hygroscopic properties rendered it useless, requiring the bullet to be removed and the chambers laboriously cleaned out. Even when fired, the gun would need cleaning at frequent intervals to prevent touch holes being blocked, and loading was a tedious process.

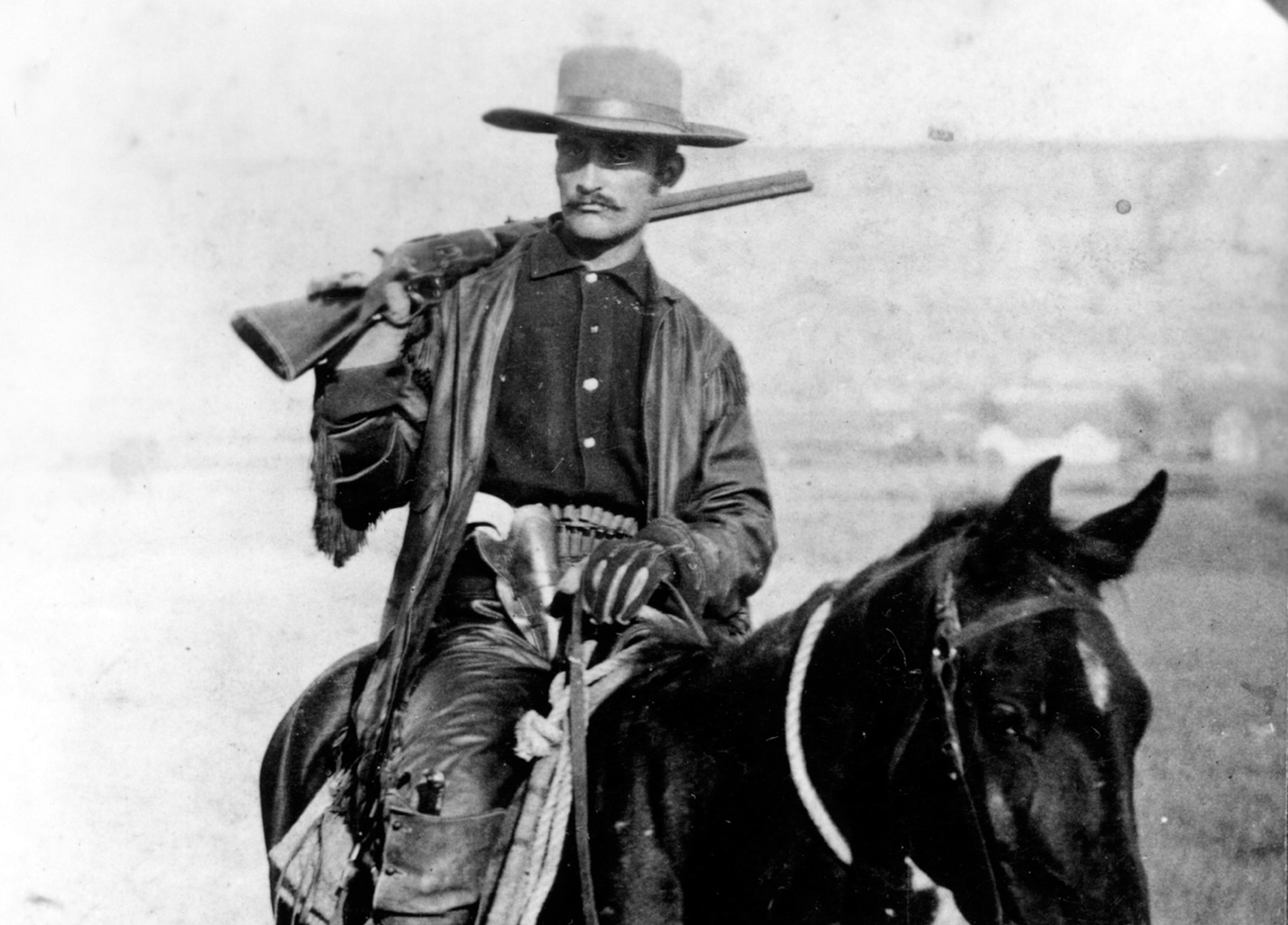

This classic Western image is actually of a Frenchman, Antoine Amédée de Vallombrosa, the Marquis de Mores. He was a titled rancher in the Dakota badlands who gained a reputation as a hotheaded gunslinger and duelist and was arrested several times for murder. He has a Model 1876 rifle resting on his shoulder. (State History Society of North Dakota)

As technology advanced and firearms design improved through the early 19th century, many of these problems were gradually overcome. Developed in the mid-1820s, percussion ignition did away with the need for separate powder priming, and revolving cylinder handguns became both reliable and commonplace in the first part of the 19th century. Several types of quite efficient breech-loading rifles appeared by the 1820s, but it was a small invention by a Frenchman, Louis Nicolas Flobert (1819–94), that would revolutionize firearms design forever. His idea was quite simple. For gallery and target shooting he placed a small spherical lead bullet straight onto a percussion cap, so no propellant powder was required. It worked brilliantly, but of course was of use only for very short ranges, which was entirely its purpose. The self-contained metallic cartridge finally made it possible to design efficient systems that were able to accept multiple charges and feed them (more or less) reliably through the mechanical action of a long-arm.

Winchester’s .30-30, arguably the most significant commercial cartridge ever introduced. It is still the most widely used caliber for hunting in the United States. (Author)

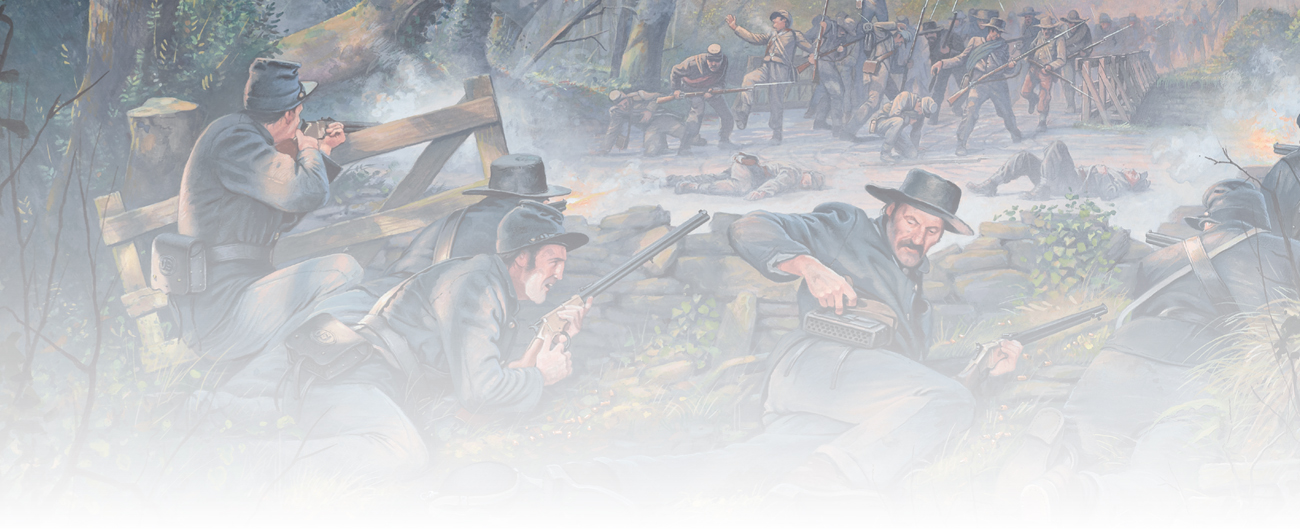

One of the first rifles to achieve this was the rimfire Spencer, adopted in considerable numbers during the American Civil War (1861–65), and it was during this incredibly fertile period that another rimfire rifle, the Henry, made a tentative appearance on the battlefield. In fact, this new rifle owed its antecedence to a series of developments that were far more complex than simply the creation of the metallic cartridge, harking back to 1848 when a primitive, but workable repeating rifle called the Volition was produced in a prototype form. It took a dozen years for the design to be honed to the point where the mechanism was reliable enough to be introduced to the commercial marketplace. Even then it was limited by the lack of suitable ammunition, for only relatively low-powered rimfire cartridges were readily available. Nevertheless, the ability for a man to have a rifle that could be loaded with 16 cartridges and fired as fast as the action could be cycled was extraordinary and potent, and demand for these repeating rifles continued to grow after the end of the Civil War. Alas, the trouble as always was that few engineers were businessmen, and many companies set up to manufacture improved firearms designs had collapsed within a year or two.

The Henry Company was no exception and would have sunk without trace had not an entrepreneur and shirt manufacturer named Oliver Winchester become the major shareholder of the old company. In taking control he also acquired the considerable engineering abilities of Benjamin Tyler Henry. Winchester was no engineer, but he was an astute businessman who understood the need to employ people who could ensure the product was reliable and viable. In this he was providentially helped through the early 1870s by ammunition improvements that saw the demise of the old rimfire cartridges and the introduction of new and more powerful centerfire types. This advance enabled the company to expand its range of models and calibers, but it ironically also exacerbated the inherent mechanical weaknesses in the design of the rifles. Winchester was always prepared to employ the best and he took on the brilliant John Moses Browning to try to overcome the shortcomings of the lever-action used in the Winchesters, which, up to a point, he was able to do. Although Winchester died in 1880, his company, Winchester Repeating Arms, continued to go from strength to strength.