IMPACT

The Winchester’s place in history

TECHNICAL IMPACT

Supplanting the single-shot rifle

The introduction of the first repeating rifles was without doubt a milestone in firearms development, for since the 18th century the single greatest desire on the part of designers and manufacturers had been to perfect a means by which a firearm could be repeatedly discharged. As is always the case, such desires were usually limited by the available technology of the period. It is not impossible that had Benjamin Tyler Henry invented his gun a decade earlier, it would have become nothing more than an interesting footnote in firearms history. Without an effective form of self-contained ammunition to use, the design would have failed. The coincidence of Henry’s design with the perfection of metallic cartridges provided him with the wherewithal to produce a rifle that was a hitherto unimaginable leap forward in firearms technology. To modern eyes, accustomed as we are to the relentless march of modern science, it is impossible to realize exactly what that rifle represented when it first appeared.

In 1860, most of the long-arms in the world were muzzle-loading, single-shot weapons. The percussion cap had been in general use for about 30 years and the use of rifles for general service issue only for around 20 years. Combining these two technologies in the rifle-musket was considered at the time to be the greatest leap forward in arms technology since the invention of the flintlock. During the Civil War breech-loading was a novelty, and on the outbreak of war some units had even been armed with smoothbore muskets. Yet, out of the blue, one man appeared with a gun that was not only rifled but also breech-loading and fired a metallic cartridge. It could also genuinely fire one shot per second, which was almost unbelievable at a time when the best-trained soldiers could manage perhaps four shots a minute.

Little wonder, then, that many decried the new-fangled guns as impossible or unnecessary, wasteful, or just downright preposterous. So perhaps it was not entirely surprising that the Henrys were not at first a huge commercial success. The total sales of around 14,000 guns were reasonable but disappointing, yet this was as much due to public perception as the need for the mechanical system to be refined so that it was reliable. Of course, where new technology is concerned, virtually no mechanical system is perfect straight off the drawing board. It took the production of those 14,000 Henrys to show both Benjamin Tyler Henry and Oliver Winchester the direction in which they needed to travel. It also raised awareness among both the general public and the military about the limitations that their existing rifles imposed upon them. In the same way that the rifle-musket eventually supplanted the smoothbore, it was inevitable that, eventually, the same would happen with the repeater and the single-shot rifle.

On the battlefield

Just how important were the Winchesters in a military context? How great the Native American use of the Henry and Winchester rifles was in battle has been much disputed for many decades, but there is more proof emerging about the weapons used during the Indian Wars as a result of the considerable battlefield archaeology that has been undertaken over the past years. Although many locations have been closely examined, such as the Fetterman, Wagon Box, and Big Hole sites, probably the most contentious – but also the most investigated – has been the Little Bighorn battlefield in Montana. One problem in determining who fired what and at whom has been the fact that many of the scouts and civilians that accompanied Army units carried Henrys or Winchesters, as is evidenced by earlier accounts of their effectiveness in driving off Indian forays. In the instance of a large-scale battle such as Custer’s ill-fated stand at the Little Bighorn, it is certain that the troopers involved carried only service carbines (.45-70 “Trapdoor” Springfields) and .45-caliber Colt single-action revolvers, and they had no lever-action weapons. Thus all the cartridge archaeology that has been unearthed can be very specifically categorized as either Army or Indian. What has emerged is that the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors who took part were very well armed indeed. At least eight Model 1873 Winchesters were used, but this number is dwarfed by the estimated 62 Henry and Model 1866 rifles that have been identified from fired cases.

Charles H. Windolph, who survived the later Reno–Benteen fight at the Little Bighorn, said that he estimated from his direct experience a quarter of the total in terms of weapons carried by warriors were modern repeating rifles. This was a significant percentage when they were used against soldiers armed with what were generally regarded to be slower-firing, single-shot carbines. However, in 1879 the US Army conducted comparative tests to see just how effective the lever-action rifles were, and the results were rather surprising. The Henrys and Winchesters did not have the range of the cavalry Springfields – 200yd compared to 600yd. Neither did they have the Springfields’ penetration of 11in of pine at 200yd, which was slightly more than double that achieved by a .44 bullet. However, it proved a surprise that the breech-loading carbines could be fired at the rate of 29 shots in two minutes, compared to the lever-actions’ 33. This, theoretically, did not put the Army at that much of a disadvantage in an equal fight, but when used in close combat, against an enemy who did not show themselves except for a brief second at a time, then the Henrys and Winchesters must certainly have provided their owners with a firepower advantage.

One of Winchester’s own sectional drawings of the action of the Model 1894. When compared to earlier models such as the 1866 or 1872, the relative complexity of the mechanism required to strengthen it is evident. (Author)

The triumph of the bolt-action rifle

While commercial sales began to pick up with the introduction of the later Winchesters, no one could have predicted that the military would actually move away from the lever-action, in favour of the slower, more reliable bolt-action. This was not the fault of Henry, Winchester, or even John Browning, for by its very nature the lever-action could not be easily adapted to being a military arm, which needed to be tough and soldier-proof. But the real problem lay with the Winchester’s inability to handle the powerful cartridges demanded by the military. The mechanism was just too fragile to withstand hard service use and abuse, despite the best efforts of Browning to strengthen it. The tubular magazine was outdated and unsafe with modern jacketed ammunition, and even the box magazine on the final incarnation, the Model 1895, was perilously open to dirt and mud. Its use by the Turkish and Russian armies, albeit in modest numbers, did at least prove that the rifles could provide an overwhelming superiority of fire, when correctly used.

A rare picture of Russian troops on the Eastern Front during World War I, armed with Model 1895 Winchesters. The man at left has his bayonet fitted, while the soldier next to him has the lever lowered and is apparently loading his magazine. (Stefan Brinski)

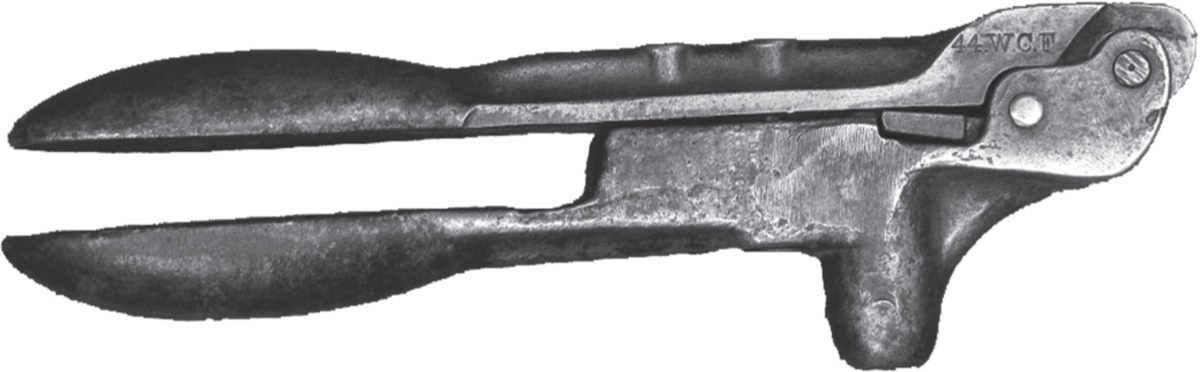

A small but important breakthrough was Winchester’s 1873 introduction of the first all-in-one reloading tool. This enabled a shooter to de-cap, recharge and replace the bullet in an empty case with one pocket-sized tool. This example, for the .44-40 WCF (Winchester Center Fire) cartridge, is one of the earliest models. (Courtesy of Antique Arms, Inc.)

Although in its later variants, the .30-caliber cartridge was quite effective, by the 1880s things had moved on and the concept of the lever-action rifle was simply not one that the world’s armies were prepared to consider. But despite the failure of the guns to generate significant military orders, the Winchesters nevertheless fulfilled a valuable role, providing generations of settlers, trappers, homesteaders, and hunters with a solidly built, reliable rifle offering a rate of fire unmatched by any other weapons. In its larger calibers it eventually proved to be a competent hunting rifle, and in carbine form it was perfect for a mounted man, providing greater range and firepower than a revolver without being too heavy or cumbersome to handle.

COMMERCIAL IMPACT

Oddly, despite being the apogee of the lever-action design, the Model 1895 was to prove the most successful military rifle Winchester ever produced, for it was widely adopted by several armies in musket rifle form. But it also led to a final split between Browning and Winchester and the ending of the agreement that the company had with John Browning. In the early years this had doubtless served both parties well, but as the success of the marque continued, it seemed to Browning that the fees paid to him, which specifically excluded any royalties, were inadequate considering the burgeoning level of sales. Indeed, so profitable was the range of lever-actions that for 40 years from 1866 the Winchester Company would not have to borrow a single cent to fund its continuing research and manufacturing, an almost unequaled record in US manufacturing history.

Although Browning was never motivated by money, he certainly felt aggrieved that the existing arrangement was heavily weighted in Winchester’s favor. Yet it seems ironic that the final split was to be the result not of money, or failure to improve the lever-actions’ designs, but because of a shotgun. In 1887 Winchester had produced their lever-action shotgun, a cumbersome design that was quickly eclipsed by their iconic Model 1897 pump-action shotgun, one of the best-selling shotguns ever and one that became a legend in firearms history, with almost 1,250,000 being produced. But times were moving on; the public were becoming more interested in new types of guns, particularly semiautomatics, and Browning had been working on a revolutionary new self-loading shotgun.

Browning’s new design was practical, reliable and potentially very lucrative but Bennett, with his inherent distrust of “new” technology, refused to proceed with it – and what Bennett said was law as far as Winchester was concerned. His attitude was not dissimilar to that of Brigadier General Ripley during the Civil War, who also believed that tried and tested technology was perfectly adequate and experimentation a waste of resources. Bennett knew and understood the lever-actions, but he disliked the new self-loaders. As Browning later wrote: “The factory was a temple and Bennett the high priest.” Browning had considerable sympathy for him, though, writing:

The automatic shotgun put him [Bennett] in a tough position. I’ll bet he would had [sic] shelled out a hundred thousand dollars just to have it banished from the earth, leaving him with his levers and pumps [pump-action rifles and shotguns]. If he made the gun and it proved a failure, as he and his advisors seemed to have half suspected, it would leave a blot on the Winchester name. Even if he made it, and it proved a big success it would seriously hurt one of the best paying arms in his line, the ’97 shotgun. If a competitor got it and it caught the popular fancy, he’d be left a long jump behind in an important branch of the business. That’s why he marked time for two years, and why, once I forced a showdown, I got so mad. (Quoted in Browning & Gentry 1987: 45)

Bennett’s reluctance to take on the new gun and Browning’s refusal simply to hand over the patent rights with no royalty agreement caused an impasse that led to a final break between the two and the ending of a partnership in 1902 that had endured successfully for 20 years. Others were not slow to take up the new design. Browning went to Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre in Liége, Belgium, a company that positively jumped at the chance to manufacture the new design. Remington Arms took on the manufacturing rights in the USA and began producing their hugely popular semiautomatic shotgun range in 1905; within a few years, semiautomatic rifles and shotguns had created a whole new marketplace in the firearms industry. It was by no means the end of the manufacturing of the lever-actions, but it lost Winchester the edge the company needed to keep ahead of its competitors and it subsequently took ten years of experimentation for the firm to come up with its own design.

In spite of the financial success of the August 1914 Russian contract, which netted Winchester $10.95 million ($190 million/£121.3 million today), such sporadic military sales were insufficient to warrant the continual production of the Model 1895 rifles, which had generally sold poorly to the civilian market, and in 1940 production belatedly ceased. This did not, of course, signal the end of the marque as other models, such as the Model 1892 and Model 1894, continued to sell well, but it was perhaps an indication that times and tastes were changing; before long, that change would mean the death-knell for Winchester.

The action of the Model 1894 open, with a .30-caliber Winchester cartridge about to be chambered. To date over 5.5 million have been sold. (Laurie Landau/Bob Maze)

Despite the company’s reputation for manufacturing lever-action rifles, one of its greatest financial successes was the tiny Model 1903 .22-caliber self-loading rifle, the design of which has remained unchanged to this day. By the late 1920s Winchester had diversified into different areas of sporting goods, hardware, tools, even batteries, but it had conspicuously failed to maintain its brand leadership in respect of its firearms. Other makers such as Marlin, Savage, and FN Browning were proving tough competition and the demand for the old lever-action rifles had tailed off. In 1931 Winchester Repeating Arms went into receivership and was bought by Olin Industries in 1944. Through two world wars, the company continued to make small arms at its New Haven plant, but its fortunes began to wane in the wake of the glut of firearms that appeared post-1945. Additionally, the design of Winchester’s guns was simply too labor-intensive to be competitive, and by the 1960s the company was in dire straits. In the wake of spiraling labor costs through the 1970s, allied to a bitter strike in 1979–80, it was believed firearms could no longer be profitably manufactured. A poorly judged attempt to manufacture cheaper rifles was largely shunned by the public. In 1980 the company was sold to its employees, becoming the US Repeating Arms Company; sadly, this merely proved a stopgap measure and it went bankrupt in 1989, the assets being sold to FN Herstal. The New Haven factory closed in January 2006, although Olin continued to manufacture Winchester-brand ammunition.

However, new generations of shooters imbued with the history associated with Winchester rifles began to create a demand for a product that was no longer available. In 2008 Fabrique Nationale d’Herstal of Belgium, who had purchased the Winchester name, resumed manufacture of some iconic Winchester lever-action models such as the 1885, 1886, and 1892, and in a landmark decision, resumed production of the hugely popular Model 1894 lever-action as well as other modern designs. Other models are being manufactured under license in Japan. In a final, fitting tribute, exact replicas of the original Henry rifle can now once again be bought from the Henry Rifle Company of New Jersey – and they are made in America.

A Winchester flyer showing the available Model 1892 rifles. From the top these are the Sporting model, De-luxe half-stocked model, the extremely popular saddle-ring carbine, the unusual short-magazine carbine and the military musket. The cutaways illustrate how the toggle mechanism had to be strengthened to cope with the more powerful cartridges. (Author)

CULTURAL IMPACT

It is usually very difficult to decide exactly what effect the introduction of a single type of small arm has had on society in general. Usually, the answer would be “minimal.” Sometimes the type of gun itself proves to be such a radical step forward in mechanical development that it acquires for itself a place in the technical hall of fame, without necessarily achieving huge sales or fame in combat. The Gatling gun could well be cited as an example of this, being the first truly workable rapid-fire gun. In other instances, success can simply be measured in sheer sales volume; there is little doubt that in terms of technology the AK-47 would not even make it into the top ten, for its basis was that of tried and tested designs that pre-dated World War II; the AK itself is not revolutionary. But its production success has been nothing short of phenomenal, with world-wide manufacture of the AK and its variants approaching the 100 million mark, and it is the most prominent firearm seen in television news footage today. Sometimes fame rests upon the visual rather than the commercial, for some firearms have achieved an iconic status without being either particularly efficient, or unusually technically advanced. The Luger semiautomatic is possibly the most immediate example of the former, for while it borrowed the beautifully made and complex mechanism from the earlier Borchardt pistol, it was neither very accurate to shoot nor reliable in the field, but almost anyone with even the sketchiest knowledge of guns will recognize one. As an example of the latter, the Colt single-action must rate among the top contenders.

Then there is a category of guns that transcends all of the reasons outlined above. They were the first examples of their genre, they changed the perception of what a firearm could do, they sold in their hundreds of thousands and still continue to be made to this day, and they spawned imitators, creating a huge collector network. Moreover, they became the industry standard for film and television, resulting in exposure (some might say over-exposure) to the public at large on a scale far beyond that of any other firearm. The two guns that immediately spring to mind are the Winchester rifle, and Colt single-action revolver, but of the two, it is only the Winchester that fulfills all of the criteria that make it unique. The Colt, for all its popularity, was merely an advanced variant of existing revolvers and it utilized no really advanced technology. On the other hand the Winchester – or more specifically the Henry rifle – transformed the long-arm from a cumbersome, slow-firing weapon to a rapid-fire, take-anywhere arm that was as practical on a wagon-train as it was in the hands of a hunter or soldier. Not only could it be fired from horseback, it could be loaded as well, something that could not be easily done with most other rifles.

Considering how relatively short the era of the American West was (generally cited as starting with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and lasting to about 1900), its legacy has remained undimmed to the present day. To a great extent this has been due to the powerful imagery used to depict that time. But it was particularly the medium of cinema that was to enhance and perpetuate the myth of the Old West, and it did so by prominently featuring the one tool that above all others made the conquest of the West possible – the firearm. Guns became a focal point of many of these films, and their constant exposure led to generations of film-goers, who had little or no physical contact with guns, being able instantly to identify the firearms being used. Indeed, one of the very first cinema films ever made was a ‘western’ called The Great Train Robbery, in 1903. Of all of these guns, two makes stand head and shoulders above the rest: the Colt revolver and the Winchester rifle. In fact, so frequently were they the only firearms used in films that many people could be forgiven for thinking that they were the only guns ever carried westwards. While this is patently untrue, it does emphasize just how powerful the big screen has been in shaping a view of history that is not accurate. Most of the main Winchester models have featured at some time on the big screen, but as film-makers have become more accurate in their portrayal of the myriad guns that were used in the West, so there has been a greater exposure of some of the models that have hitherto been overlooked.

Probably the best example is the Henry rifle, which for all its historical importance, was never used in a film until 1962, when one was carried by Henry Fonda in How the West Was Won. In fairness, it might be argued that the Henry, for all its ground-breaking technology, was not actually a very good rifle. Nevertheless, it was by any standards a quantum leap forward in firearms design, although that crucial fact is probably lost on film-makers. It is perhaps worth noting that shortly afterward its first appearance, a “Henry” rifle was supposedly carried in the Clint Eastwood “spaghetti western” The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966), but due to their rarity and value an altered Model 1866 was used. Eastwood is known for his interest in and knowledge of firearms and it was supposedly at his request that this contemporary and unusual rifle was represented. In four subsequent decades it appeared just eleven times in various films, but with the introduction of the new genre of “realistic” Westerns that number has been greatly exceeded since the year 2000. If the Henry was not regarded as mainstream for the film-going public, then the same cannot be said of the later Winchester models.

There were many black cowboys working the ranches in the West, and they earned a reputation for toughness and reliability. This is the picturesquely named Nat Love photographed in a studio with the tools of his trade: a saddle, rope, gun-belt, and Winchester Model 1894. (Denver Public Library)

The first Winchester to really become a screen icon was the Model 1866 Yellow Boy carried by John Wayne in the 1948 film Fort Apache. The fact that the US Army were never issued with Winchesters did not concern directors of the time. The rifles looked good, with their distinctive yellow receivers and rapid fire, which translated well on the big screen. Interestingly almost all the Native Indians were equipped with Winchester by the studios and the visual appeal of the Winchesters ensured that they were a prominent part of the Western movie arsenal from around this date. One could go so far as to say that the visual myth began at this time that no one who ventured west of the Platte River carried any guns except Colts or Winchesters.

If the Model 1866 had gained some small fame on screen, it was nothing compared to the impact that the Model 1873 was to have. If the Winchester had not quite achieved icon status by then, it did after the film Winchester ’73 starring James Stewart came out in 1950. The film was unusual for several reasons, for it was the first time in movie history that a film was made specifically about a firearm. It also wove a certain amount of truth into the plot, portraying the Indians who fought at Custer’s ill-fated battle at the Little Bighorn as predominantly carrying Winchesters, which was at least partly true. But it also advertised the little-appreciated fact that Winchester had produced a range of expensive and rare limited editions, marketed as the “One of a Hundred” and “One of a Thousand” rifles. Indeed, so keen was the director of the film, Anthony Mann, for authenticity where the rifles were concerned, that an appeal was launched through the gun press and by means of 150,000 posters appealing for information on the whereabouts and numbers of genuine surviving “One of a Thousand” Model 1873s. As a result they found 23 and used one for the film, with James Stewart reportedly being presented with the rifle after the end of filming. The Model 1873 rifle arguably became more famous than many actors of the period, making 44 appearances in subsequent films.

Without a doubt, though, the single most influential figure to use the Winchester was John Wayne, who had a personal liking for the models and carried them in no fewer than 40 films. In 11 of those films he carried a Model 1894 saddle-ring carbine with a modified large-ring ‘Mare’s leg’ lever, most memorably for his performance in True Grit (1969) which finally won him both a Golden Globe and an Oscar. On the small screen the Model 1892 also became the star of a hugely successful television production, The Rifleman, starring Chuck Connors, who also carried a large-ring Model 1892 throughout the series, which ran from 1958 to 1963. The author recalls watching the programs as a small boy and vowing to own a Winchester ’92 one day, which sadly he never has. This was not the case for Connors, who was personally presented with two of the Winchesters. It could even be argued that in terms of film appearances, for sheer numbers the Model 1892 deserved its own Oscar, as to date it has been used in no fewer than 73 films and a dozen TV series. Sometimes the visual need clearly overcomes the historical where film studios are concerned. In the 1941 film, They Died with Their Boots On, the Indians fighting at the Little Bighorn in 1876 were portrayed carrying Winchester Model 1892 rifles!

Although almost indistinguishable from the Model ’92, the Model 1894 must come a close second in terms of screen-time. For some reason it never quite seems to have held the visual appeal of its predecessor, but has still managed 40 films, and one features frequently in the TV series Longmire. Most of its use has been post-1960, possibly because of its similarity with earlier types and the ease with which the model can still be bought. This makes it more attractive and cost-effective to use, particularly in more modern times, when prices for original rifles have become very high. There is also the requirement for these guns to fire blanks and the more modern calibers’ chambering make it easier for film armorers to secure the sometimes large quantities of ammunition needed. The last of the lever-actions, the Model 1895, is still rather under-represented on the big screen, having a mere 18 appearances to its credit, the majority of them relatively recent. It is perhaps an indication of how producers have been looking more closely at historical accuracy than in the past. In the 1969 film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid the Bolivian Army are shown using Model 1895s; there is evidence that Mexico actually sold several hundred to Bolivia.

The surge of interest in Western firearms has meant that there are many good reproductions available, and most of those seen on screen will be modern Italian- or US-made copies; these are cheap and in many instances, arguably better made than the originals. This has greatly enlarged the potential arsenal from which film and TV companies can pick for added historical accuracy. There are, for example, more Henrys available today than there were when they were in production.

A Welsh immigrant, David Hughes, who worked in Arizona towards the end of the Western era. He is pictured here (c.1896) in his work clothes. Wrinkled trousers, stained shirt, frayed leggings, and dust-covered boots are evidence of a man who has just climbed off his horse. His rifle is the Model 1894 carbine; the revolver appears to be an unusual Colt Bisley model. (Arizona Historical Society)