1

AN EXPERIENCE OF POWER

The Unsuspected Immigrant and the Invisible Institution

The Voodoo rite of possession by the god became the standard of American performance in rock and roll. . . . Which is not to say that rock ’n’ roll is Voodoo. . . . But it does preserve qualities of that African metaphysic intact so strongly that it unconsciously generates the same dances, acts as a major antidote to the mind-body split, and uses a derivative of Voodoo’s techniques of possession as a source, for performers and audience alike, of tremendous personal energy.

MICHAEL VENTURA, “HEAR THAT LONG SNAKE MOAN”

How can you have the expectation of freedom in an unfree world unless you’re in touch with a freedom that judges history, but is independent of it?

TOM SMUCKER, PRECIOUS LORD: NEW RECORDINGS OF THE GREAT GOSPEL SONGS OF THOMAS A. DORSEY

SOMEDAY, maybe, there will be a history of ecstasy, an academic discipline of ecstasy. If so, one of the important lessons of this future history will be that the migrations of ecstasy do not accompany power. This history of ecstasy will be very different from the history of civilization, though ecstasy is the seed of civilization. If we try to trace ecstasy’s movement by consulting the stories of kingdoms and empires, even the stories of peoples and ethnicities (though that is closer), we will miss it.

The historian will find that ecstasy has a complicated relationship to history. Sometimes ecstasy and the historical record come together; sometimes it even seems like ecstasy is the heart of history. More often it will seem like ecstasy is the particular treasure of the poor, the dispossessed, and persecuted. “What we find over and over again in a wide range of different cultures and places is the special endowment of mystical power given to the weak,” says anthropologist I. M. Lewis.1 The path of ecstasy will be hard to predict—the spirit blows where it will.

But one place the future historian will sooner or later look is a dark line across the Atlantic Ocean, from Africa to the Americas, from the Bight of Benin to the New World. This is of course the Middle Passage, the route of the enslaved West Africans who were taken by the millions to the Americas. The future historian will learn to look for ecstasy in the pit.

For almost three centuries the slave ships crossed the South Atlantic, taking ten to twelve million Africans from their lands into hopeless lifelong servitude, to be released only by death. But here’s where the upside-down nature of the history of ecstasy comes into play: for the societies that the slaves were taken from were built around ecstasy.

The Africans were taken from many tribes and kingdoms, and each had its distinctive culture. But they shared important things too, especially a religious sensibility. Except that what we think of as “religion”—a name for a certain aspect of life—to the West Africans was simply life. The world of the gods, the world that gave sacred meaning to things, was quite close and accessible, intermingled with the actions and things of day-to-day life. The divine was not a realm beyond experience. Everything was felt to express it. The intuition we in the West have from time to time of the vivid significance of all things, animate and inanimate, they had too, but in Africa they built cultures around it.

At the center of their religious life was the dance where the spirit, the gods, became embodied in the people. Anthropologists call it “possession,” but it is just as accurate to call it ecstasy, when an influx of great spiritual power works through a human person, and ordinary consciousness, acknowledging the greater power, relinquishes its grip on the individual. Music, rhythm, and dance were the liturgy and the technique by which the ecstasy was invited and induced. The rhythm created by the drummers was the heart of the process, a sacred art. A drummer could manage the flow of the ecstasy through his rhythm, could induce different gods to descend with different rhythms.

Through these complex sounds, the drummer led the people to a central silence, a still point where the god can enter. In embodying the spirit, each “possessed” dancer became an oracle, a prophet, or a prophetess. The community could come to know the god by watching the dancer. Wherever the Africans went in the world, the dance and the rhythm would go on. But first they were taken from the land where they danced with the gods.

The Middle Passage killed two and a half million Africans, chained side by side in the oven heat and the unbreathable air in the holds of the ships. The lesson that the Middle Passage was designed to teach the enslaved was that they were indistinguishable from the shit they lay in, that shit was their nature. But the Middle Passage was just the first stage of the process. Upon landfall the people who survived it were taken to the “seasoning camps,” where they would undergo a period of sustained humiliation and torture. Special emphasis was placed on breaking the resistance to having their genitals handled. This sometimes went on for years, until the captives seemed completely broken. About one-third, or five million, of the people who went into the seasoning camps died there.

This system was a program devised to root out and shatter the core of the self, or to only leave as much of the self as was necessary to do work. We might assume that the result of this treatment would be fragmentation of the psyche into psychosis or catatonia. But there were aspects of the self that the slavers were not aware of, but the Africans were. It was likely that the enslaved man or woman had known ecstasy.

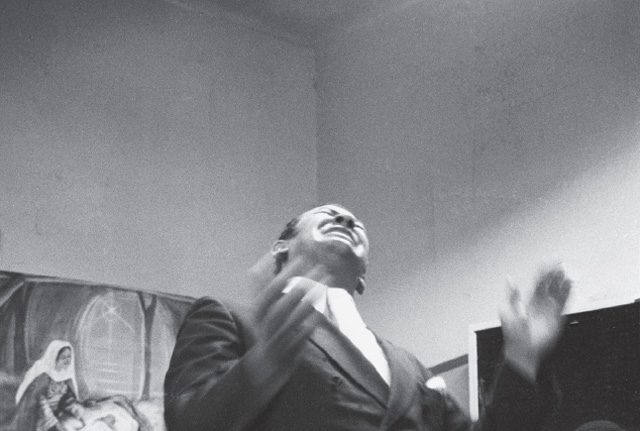

Fig. 1.1. Preacher at a storefront church, Cleveland, Ohio, 1971 (photo courtesy of George Mitchell)

In one sense, ecstasy is the difference between being and nonbeing. Ecstasy and existence are twins. Even in the most degraded state of being, there is an infinitely small particle that implies the fullness of being. As long as there is that particle of being left, there can be ecstasy, and full humanity can still flower. The enslaved ones with their ecstatic training knew this. Ecstasy is the core human experience, and confirms being at the deepest level. The ecstatic does not believe, she knows that her being participates in Being itself. This feeds and fortifies the human core that it was the precise intention of the slaver to diminish or destroy.

Over time, everywhere they were, the slaves, through one stratagem or another, created a space where they could begin to assemble from their shattered systems of ecstasy new syntheses—Candomblé, Voodoo, Santeria, the black church—to nurture ecstasy in some kind of community and to give it to their children.

The dominant spiritual tradition among whites in the New World was Christian—Protestant in North America, Roman Catholic almost everywhere else. The slaves synthesized a new tradition of Christian symbol and West African practice. This religion of the slaves gave the masters everywhere uneasy sleep, and with good reason. Ecstasy may begin in powerlessness, but in the world of the slaves, ecstasy implied community, and community begins to give power. Just as “in dreams begin responsibilities,” so in trance begins politics. We see the connection between ecstatic music and dance and social transformation again and again in the rise and spread of the slaves’ culture, first in the Americas and then around the world.

Just as the Freemasons created an underground network of radical thought that nurtured the revolutions of the eighteenth century, in Haiti the Voodoo societies created a network and structure among the slaves that enabled them to rise and throw off their French masters in 1805. Across the enslaved Americas, ecstasy powered resistance. “So we find the candomblé serving as ‘centers for insurrection’ in early nineteenth-century Brazil, and Santeria gatherings in Cuba linked to slave revolts,”2 writes Barbara Ehrenreich.

Voodoo enters North America through Catholic and Caribbean New Orleans, and it’s out of New Orleans that black American music would eventually emerge to conquer the world. It’s where the African dance enters North America. New Orleans was very much separate from the culture of the young United States. It was not Protestant. It was not Anglo-Saxon. There were many “free men of color” in New Orleans. In New Orleans slaves were still slaves, but they could dance and they could practice Voodoo. As it had many times in the past—as far back as the Roman Empire—Catholicism offered a strange free space, born of its long acquaintance with paganism, where the imagination of the Africans could enter and engage with the stories, images, and sacraments of the church, just as Congo Square, New Orleans, opened a space for the slaves to dance.

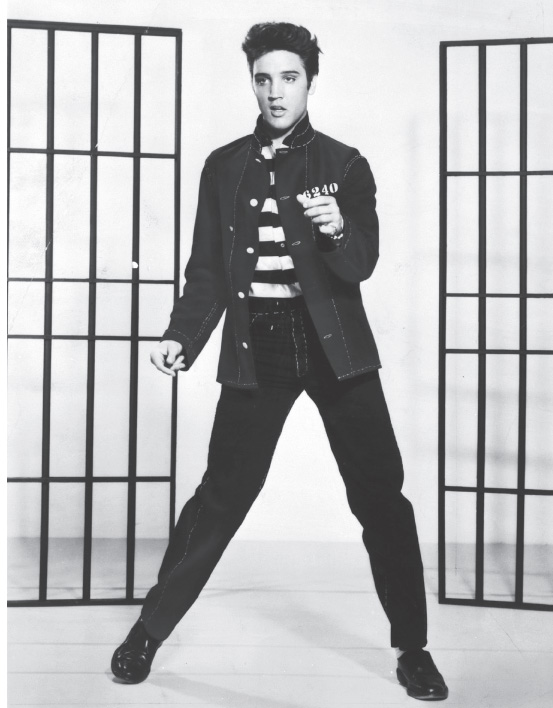

American music proceeds from Congo Square. It’s in New Orleans, as Michael Ventura says, that the music and dance for the first time are separated from the religion, taken out of the liturgy, and turned into performance. This is how jazz begins. But, Ventura says, the music yet contained the metaphysic in itself. The music transmitted the religious idea and instructed new dancers unconsciously. (Watch the young Elvis. Few white people had ever seen anyone move like he did. He was never taught it, but he didn’t exactly invent it. The music taught even white boys how to move.)

But the “invisible institution” of slave spirituality also entered North America from the east, through the plantation system that spread across the American South from the Tidewater plantations along America’s mid-Atlantic coast. The first Africans came ashore at Jamestown in 1619, and began to create the Cotton Kingdom.

But Virginia, Carolina, and Georgia are not New Orleans, not Catholic. There were no mass gatherings of slaves to worship and dance. Gatherings of even the smallest number were forbidden. By and large, the planters perceived slave religion—even slave Christianity—as a clear and present danger. Baptizing a slave was the thin end of a wedge whose wide end was acknowledging the slaves as human. And that, of course, had implications that could (and eventually did) turn the Cotton Kingdom upside down.

Beneath the juggernaut wheels that powered the Cotton Kingdom, in what seems a condition of almost absolute weakness, the slaves again found a way to fan the spark of ecstasy. There were not enough overseers in all the South to police the life of the slaves absolutely; and though the space allowed for a culture to develop was desperately narrow, it turned out to be enough.

One of the earliest and most enduring liturgical forms of African American Christianity was the ring shout. There are descriptions of it from precolonial times to World War II. Gospel music, soul music, and rock and roll would each in their own way preserve elements of the shout and place them near the center of their traditions. In the shout, people form a ring and begin a shuffling counterclockwise dance, clapping and stomping their feet so that the wooden floor takes the place of the forbidden drum. A shout leader stands outside the circle, calls out the verses of a song and the dancers respond, line by line. A “band” sometimes stands outside the circle alongside the leader, providing the shouters with a counter-rhythm to the slapping of the feet on the floor, a pattern that would one day become famous as the “Bo Diddley beat.” The slave “spirituals” came out of the shout; they were songs first made to be “shouted.”

Fig. 1.2. A young Elvis Presley, 1956

And when ’twas night I thought ’twas day,

I thought I’ d pray my soul away

And glory, glory, glory in my soul!

(chorus)

O shout, o shout, o shout away,

And don’t you mind

And glory, glory, glory in my soul!

Albert Raboteau says that the shout “created the experience it described.” The words of the shout described the glory, but the shout was also a technique to bring down the glory into the minds and bodies of the shouters, to be experienced that very night.

The shout, in addition to being a dance and a song, is also a drama. The text, the lyric, is a Bible story. Joseph M. Murphy describes it this way:

As the participants sang repeatedly, “We’re traveling to Immanuel’s land,” they would move through the gestures of Joshua’s army surrounding Jericho or the children of Israel leaving Egypt. The construction of the sacred space of the ring allowed them to participate in the mighty events of liberation, to incarnate the successful struggles of the biblical ancestors into the harsh worlds of slavery. . . . The idea of freedom is made physically present in the bodies as well as the minds of the participants. . . . Ceremonial freedom was a pattern or archetype of liberation.3 (my italics)

The immediacy and accessibility of the freedom that the people experienced in the shout is a key to the eventual victory over Jim Crow. On one level the people of the Civil Rights Movement were working to create a new condition in society; but on a deeper level they were manifesting a liberation that already existed outside of time or history. Participants in the shout experienced liberation as a present reality. By living that reality, their descendants manifested that timeless fact in the world of time, in the American South of the 1950s and 60s.

The interplay between the experience of timeless essential freedom and historical freedom—between spiritual liberation as a metaphor for historical liberation, and historical liberation as a metaphor for spiritual liberation; between myth and history; between the inward experience of the individual and the outward experience of the community in the world—this is the particular contribution of African American Christianity to the spiritual traditions of the world. And the music and rhythms are the foundation of it.

Gospel music as we know it took shape toward the end of the nineteenth century. The matrix was the black Pentecostal church—the “holiness” or “sanctified” churches.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, many black Christians had begun to take on the more sedate worship style of whites. The African part of African American Christianity began to recede. The Sanctified Church was a revolt against that drift. Zora Neale Hurston wrote in the early 1930s: “The rise of the various groups of ‘saints’ in America in the last twenty years . . . is in fact the older forms of Negro religious expression asserting themselves against the new. . . . It is putting back into Negro religion those elements which were brought over from Africa.”4 Cheryl Townsend Gilkes describes the Sanctified Church tradition as a “black cultural revolution” that “fueled the sacred and secular popular culture of the American South and eventually the entire culture.” In the Sanctified Church music is the central element in the ritual that leads to possession by the Holy Spirit. “[T]he anointing of the Holy Spirit is the . . . objective of a gospel performance,” says Gilkes. “Will the performance encourage emotional release, spirit possession, shouting, conversion experiences? The task of the musician is to elevate that message . . . so that people are moved to hear and respond to it as a life-changing experience.”5

The Sanctified Churches welcomed and found a liturgical use for any musical instrument that a member might bring. In the Sanctified Church the descendants of slaves got their drums back—as well as amplified guitars, keyboards, horns, and tambourines. By the 1940s the pattern of the rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll band begins to emerge—rhythm and lead guitars, bass, keyboard, a charismatic preacher out front.

By the 1940s Sanctified-style gospel music had expanded to most denominations of the black church. As the tradition developed it turned out performers and composers of genius like Thomas A. Dorsey, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Mahalia Jackson, and the gospel quartets like the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Soul Stirrers. Gospel experienced a golden age from the 1940s to the 1960s.

But of course the music was not developing in a vacuum. Tectonic plates of history were grinding against one another. America’s “original sins” of slavery and racism had not been expurgated, not even by the massive bloodshed of the Civil War. An electric spirit of freedom was rising. The timeless drama of liberation that the black church had ritually enacted for centuries was about to ground itself in the earth of the American South. The ecstatic art of gospel music was approaching its intersection with history.

From the start gospel music was in conflict with the white supremacist regime. The rise of gospel music coincided with the high point of racial terror in the South. At the peak of the terror, between the 1890s and the 1920s, scholars have estimated that two or three blacks were lynched each week. As it had in the African diaspora from the start, the musical practice fueled resistance even to the most brutal repression.

The “gospel experience” of possession by the Spirit advanced the freedom movement, as we’ve said, by providing an immediate experience of a person’s irrevocable freedom. But shared ecstasy also generated an intense and highly resilient sense of community. Michael Castellini describes how “as the performance moves toward the transcendent gospel experience, ritual participants rejoice as they approach a state of ‘spontaneous communitas . . . a ritualized experience of intense human interrelatedness and lack of social hierarchy’ that occurs during many rites of passage . . . associated with mystical powers believed to be sent by deities or spiritual ancestors.”6

Participation in the stories of liberation like the Exodus from Egypt, “supplied the Civil Rights Movement with the alternative world-views . . . that challenged the logic of white supremacy,”7 Castellini says. The movement actualized the core message of the Exodus story and of the ministry of Jesus—the last becoming first and the first last, God standing with the oppressed against the powerful.

In practical terms the black church gave the Civil Rights Movement its institutional center and logistical structure. It supplied places to gather, leadership from its ministers, and a mass base to mobilize. The regular mass meetings, which were the basic organizing, communication, and community-building tool of the movement, were closely patterned after gospel services. They were held in churches and filled by people who lived with the traditions of the church. Meetings included such gospel elements as prayers, testimonies, oratory, singing, and donation collections. These similarities, says Castellini, were “among the . . . most profoundly significant aspects of the Civil Rights Movement.” Castellini calls this a “gospelization” of the movement. Without it, he says “it is questionable whether the . . . Movement would have been as effective and successful as it turned out to be.”8

In the 1950s the Reverend C. L. Franklin was probably the best-known black preacher in the United States. He’s been called “by far the greatest ‘gospel preacher’ of them all.” He was also the father of Aretha Franklin, who is arguably the greatest of all the soul singers, and who grew up singing in his church.

The intimate connection between gospel music and soul music is and always has been obvious. But let’s say it just once more (or rather let Michael Castellini say it): “Probably without exception [emphasis added] . . . soul singers got their formative musical experience in the gospel church.”9 The connection is so clear and pervasive that it is easy to think of soul music, especially the “deep soul” of the South, as simply gospel music removed from the liturgy with a human beloved substituted, in the lyric, for God or Christ: the strictly phenomenal elements of being “taken up in the spirit” or “getting happy” transferred to the dynamics of the secular performance and the dance that it inspired. But it’s important to remember Michael Ventura’s intuition that, even with the explicit religion ostensibly taken out, the metaphysic of the embodied spirit remains encoded in the music, in the performance and the dance. The deep power of soul music depends on that being true.

Fig. 1.3. Aretha Franklin, the queen of soul

(Billboard, 1967)

In the 1950s and ’60s a cohort of exceptional gospel-trained performers entered the rhythm-and-blues market, came to dominate it, and in the process created a new style. We’ve mentioned Aretha. There was also James Brown (of the Gospel Starlighters), Sam Cooke (of the Soul Stirrers), Curtis Mayfield (of the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers), Solomon Burke (consecrated a bishop at birth), Ben E. King (whose “Stand By Me” was a version of the gospel song “Lord Stand by Me”), Otis Redding, Little Richard, Sam and Dave, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Rufus Thomas, Jackie Wilson, Marvin Gaye, Eddie Kendricks and David Ruffin, Martha Reeves, Al Green, and the Staple Singers—among others.

Because of its connection to the church, the new gospel-style R & B became known in the black community as “soul music.” White audiences who began to be attracted to soul music heard what was to them an exciting new fervor and commitment. The testifying quality, the clear sense that there were deep stakes involved, that there was a message that urgently needed to be put across, this was thrilling in a way that was new in popular music, if not in the church. People couldn’t stop listening to these performers who had understood from childhood that the responsibility lay on them to bring down the Holy Spirit.

A sister southern music, creating its first stars and hits at the same time as soul, also performed by people with Pentecostal backgrounds, was being called rock and roll.

In their transit from the church to the jukebox, soul performers brought the emotional depth of gospel with them, but not necessarily the extremes of behavior that the Holy Spirit could inspire, not necessarily the final push that could tip a congregation into ecstasy. But some of the new rock-and-roll performers—like Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis—seemed to want to bring the extreme style of the most spirit-filled preachers, the preachers who knew how to rock the house, into their show. The rock-and-roll singers, in effect, homed straight in on possession.

Musicologists have devoted a lot of energy to the question of where the name rock and roll comes from. A likely source is the ring shout. When the shout takes on its own momentum, the participants are rocking. “I gotta rock, you gotta rock,” says the shout “Run Jeremiah Run.” When the spirit is really moving through the congregation, they are rocking the church. But wait—haven’t we always heard that to “rock and roll” means to have sex? Yep. So does it mean sex? Yes. Does it mean religious ecstasy? Yes. One of the gifts of the black church to spirituality in general is the insight that the sensual and the sacred are, in a mystery, the same thing. It’s this that made the transit from church to jukebox not simply a case of parlaying sacred tradition into hits, as if the spiritual part of the music was a clearly marked zone that the performers could just step out of. In turning from gospel to soul the musician is not so much moving from sacred to secular, leaving his or her calling for the world, but shifting the emphasis from one part of the spiritual spectrum toward another.

The standard narrative about the origin of rock and roll as a music is that it came out of the encounter of country music and the blues. This isn’t exactly wrong, but it almost willfully ignores the glaringly obvious affiliation with gospel music.

The blues are often regarded as the primordial source of black American music, indeed of modern American popular music in general. But the blues are not the primordial music of African America. The blues and gospel music started to gain popularity in roughly the same era—around the turn of the twentieth century—and, for that matter, were both heard as novelties at the time. In the long story of African American music, the sacred precedes the secular. The roots of gospel are in the spirituals that date to the earliest slave culture, generations before anyone sang anything that people called the blues. A truer picture is to see the blues and rock and roll as related offshoots of African American sacred music.

You can certainly hear early blues in 1950s rock and roll. But as you try to trace the “blues-into-rock-and-roll” genealogy, you come to a gap that requires an act of faith or imagination to bridge, for there is a certain kind of frantic jubilation in rock and roll that is not generally characteristic of the blues. But between gospel music and rock and roll, there is very little gap to jump. It’s almost all there—the emotional intensity and momentum; the central tension-and-release dynamic; the manipulation of levels of excitement in the audience; the electricity and amplification; the guitar, bass, drums, and keyboard configuration (not forgetting tambourines); the choral background; the invocation of a great noise to symbolize or channel power to the community.

As musical forms, the blues and rock and roll are very similar, but the performance of rock and roll—and the audience participation inspired by it—is modeled, consciously or unconsciously, on the liturgical practices of the gospel church. What most distinguishes rock and roll from the blues is what most links it to gospel music—the pursuit of ecstatic release as the goal of the performance. The gospel belief that music and motion can effect a change in consciousness—as well as the conviction that the congregation/dancers are getting a purchase on freedom that might outlast the performance—reappears more obviously in soul and rock and roll than it does in the blues.

In support of the gospel origins of rock and roll, we can call on some of the great names to testify. Elvis Presley tells us in his 1968 “Comeback Special” that his rock and roll is essentially gospel. While young bohemians in London were hunting out Elmore James records in the early sixties, up in Liverpool the Beatles were apparently not listening to the blues at all. Aside from early rock and roll, the stuff the Beatles seemed to like, based on the songs they covered, was black pop that had a church lineage—soul music and girl groups.

Gospel music is the elephant in the room when it comes to rock historiography. Partly this may be due to the fact that since the beginning most rock writers have tended to be secular, young, and white as opposed to devout, mature, and black. The blues is a medium of individual artists, outlaw heroes, easier for bohemians to admire and identify with than a faith community. For most rock critics the juke joint is easier to negotiate (at least imaginatively) than the storefront church. And for many white intellectuals, there is a double barrier to empathy with gospel music—both race and religion. It can be tricky work for a white person to write about black music without sounding gauche. But the additional challenge of trying to think one’s way inside a Pentecostal religious community has daunted all but a few.

The blues could be detached from its cultural matrix and listened to as pure music more easily than gospel. The blues was a genre of entertainment. Gospel music underpinned a community and a way of life. For most black Americans in the first half of the twentieth century, gospel music was more important to the life they led than the blues and more a source for resistance when the crisis came. But to imagine religious music as a revolutionary force sets up a sort of cognitive dissonance for a lot of music writers. In the end most have been content to give gospel a respectful nod and move on.

In any decent history of rock music you will of course find blues musicians discussed, but you’ll have to look harder for gospel singers. Gospel may be cited as an influence, but individual artists are almost never dealt with at length. While up there in music heaven, Sister Rosetta Tharpe keeps playing something that sounds a lot like subsequent rock and roll, more so, even, than what you hear on Elvis’s first sides. There are some seventeen blues musicians represented in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There are two gospel acts—Mahalia Jackson and the Soul Stirrers (both in the “Early Influences” category, none among the regular inductees). The “Sidemen” category still excludes Elvis’s famous backup group, the gospel-singing Jordanaires.

As we’ve said, the future historian of ecstasy will come to see that spiritual impulses are transmitted along unpredictable and paradoxical paths. By the late 1950s young white Americans were dancing en masse to music that was a product of centuries of African American spiritual practice. The lesson that what is trivial through one lens can be mighty through another will be another valuable discovery made by our ecstatic historian.

The music began to teach these young people to expect an experience of the embodied spirit in their dancing and to look for a kind of truth and consequentiality in the music itself. They absorbed the gospel knowledge that liberation and ecstasy could come by way of popular music, and that it could leave an imprint on history as well as on the individual soul. That the music in this lineage could connect the divine and the mundane was a message that never left the music. It carried the code through every change and crisis. Sometimes the power was more potential than actual, but it was always there. The promise was not lost on the cohort of young people who would create the 1960s heyday of rock and roll.