6

EARTHQUAKE COUNTRY

The Grateful Dead, Acid, and the Mythic Life

IN FOLK musicology there is a category of song called cumulative or counting songs. The lyrics of the cumulative song accumulate—that is, one new line of lyric is added each time a new verse is sung. The best-known example is probably “The Twelve Days of Christmas”—each time you sing another verse you add a gift your true love sent until you’ve got all twelve. In a lot of cumulative songs, the items enumerated are fantastical or obscure in their meaning. The leaping lords and milking maids of “The Twelve Days” are a kind of nonsense verse or fairy-tale imagery. The point is to remember and be able to sing all the accumulated items by the time you get to the last verse. There are a lot of these songs, some very old (the first version of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” is found in Thomas D’Urfey’s 1719 Pills to Purge Melancholy) and some even older (for centuries, “Echad Mi Yodea” has helped Jewish children learn the Passover story). And some are relatively new—“I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly” was written and recorded in the 1950s.

Of them all, one of the oldest and most cryptic is “Green Grow the Rushes, O.” It begins:

I’ll sing you one, O

Green grow the rushes, O

What is your one, O?

One is one and all alone and evermore shall be so.

You respond to the questioner in each verse, adding a new item each time until you reach the twelfth, the magic number of wholeness. Here is the whole list when you get to the end:

Twelve for the twelve Apostles

Eleven for the eleven who went to heaven,

Ten for the Ten Commandments,

Nine for the nine bright shiners,

Eight for the April rainers,

Seven for the seven stars in the sky,

Six for the six proud walkers,

Five for the symbols at your door,

Four for the Gospel makers,

Three, three, the rivals,

Two, two, the lily-white boys,

Clothèd all in green-o

One is one and all alone

And evermore shall be so.

The song’s age and origin are unknown. A counting song with similar lyrics was sung by English children in the early 1800s. By the 1860s it was heard—still being sung by children—in the streets of London at Christmastime. It was officially “collected” by folklorists in the west of England at the start of the twentieth century. The meaning of the lyrics is equally obscure. They seem to be a mixture of Christian catechesis for children (the twelve apostles, the Ten Commandments, the four Gospel writers), astronomical lore (the nine bright shiners, the April rainers, the seven stars), and possibly fragments of pre-Christian folklore (the six proud walkers, the symbols at your door, the three rivals, the two lily-white boys).

The early folklorists thought the lyrics “corrupt”—that is, the reason they couldn’t be understood is because the original words had been garbled into nonsense over the centuries. But maybe that’s not the case; maybe it’s not nonsense. Maybe those three hypothetical sources for the lyrics—Christian, astronomical, pagan—were supposed to be together, were part of a riddle for which there was an answer, but one that was forgotten. Or perhaps we’re supposed to hear it in the way that we encounter a poem whose meaning may seem at first obscure but that we come to understand and even cherish when we stop trying to interpret it, the apparently random or accidental juxtapositions finally making a kind of intuitive sense.

In late 1968 the San Francisco band the Grateful Dead were fiddling with ideas that would become the material for their third album, Aoxomoxoa. They had a piece they were considering, that eventually they called “The Eleven,” which was a jam that developed into a song, in the typical way of the Dead. In the end they never found a way to make it work in the sequencing of the record. That didn’t mean that the Dead didn’t like it. You can hear “The Eleven” laid out in all its nine-minute-and-eighteen-second glory on Live/Dead. Honestly, the first three minutes are pretty boring rambunctious but uneventful blues vamping. But then something great happens. From Phil Lesh’s bass, at first, comes bubbling up out of the jam a kind of madly rolling psychedelic sea chantey spraying foam at the prow, the Dead gleefully set off, and Jerry Garcia’s lead leaps out of the muddle of bluesiness with some of his most lyric and jubilant playing, guitar lines that soar skyward, then float back down. (Keep in mind that all this happens at a crazy velocity.) The air of celebration is palpable, an apotheosis of hippie festivity.

Like some other bands of the day, the Dead and lyricist Robert Hunter had an impulse to interpret the times for their audience, to explain what was happening. Here in “The Eleven” they announce the turn of the New Age: “No more time to tell how / This is the season of what / Now is the time of returning . . . / Now is the time past believing / The child has relinquished the reins.” But just at this point in the song, for whatever reason, somebody remembers the counting song. So while Bob Weir sings about the time of returning, Jerry Garcia interpolates a zonked recollection of “Green Grow the Rushes”:

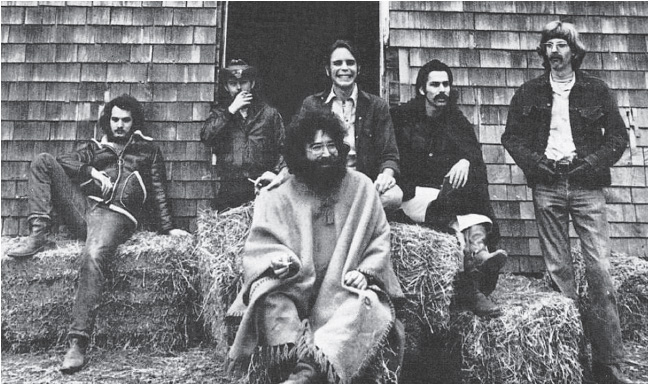

Fig. 6.1. The Grateful Dead

Eight sided whispering hallelujah hat rack

Seven faced marble eye transitory dream doll

Six proud walkers on the jingle bell rainbow

Five men writing with fingers of gold

Four men tracking down the great white sperm whale

Three girls wait in a foreign dominion . . .

. . . so that the announcement of the New Age is braided with the memory of the ancient riddle-song. As if what the Dead are doing is somehow a response to the old riddles, a way to interpret them. As if the old riddle predicted what was happening.

There are many types of sound that are associated with psychedelic music of the sixties—feedback, distortion, echo, phasing, speeded, slowed, backward, or looped tape, snippets of found sound, anomalous instruments. And you will hear very few of these things in the Grateful Dead’s music. With the Grateful Dead, it was their ideas about how to play music, not what was added in the studio that made them psychedelic. There are a few “trippy” tracks on early Dead records—the last couple of minutes of “That’s It for the Other One” on Anthem of the Sun, “What’s Become of the Baby” on Aoxomoxoa, “Feedback” on Live/Dead. But the Dead’s mind-blowing didn’t usually depend on freaking the listener out. It was done more in the manner of the trance music of indigenous cultures, where the musicians gradually draw your attention inside the process of the music, in a kind of hypnosis, tuning your awareness to the changes and nuances in the music, then, once they have your attention focused, manipulating and building the effect to an ecstatic resolution.

As coined by psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond in the 1950s, the adjective psychedelic comes from the Greek psyche—“mind” or “soul”—and delos, “to be made visible” or “be made manifest.” Something that is psychedelic makes the hidden processes of the mind manifest, the soul visible. But in a broader sense, as a category of sensibility, “psychedelic” art is recognizably a subclan of the great old family of Romanticism. When you actually listen to music from the era, it becomes forcefully clear that a lot of what is being expressed emotionally is quite close to what C. S. Lewis, along with the German Romantics, called Sehnsucht. Sehnsucht has been called an untranslatable word, but literally, das Sehnen is “an ardent longing” or “yearning” and die Sucht, “addiction.” Sehnsucht is a longing for something that is profoundly, intimately familiar to us, yet at the same time ordinarily absent from our conscious life.

From Lewis:

It is the secret we cannot tell and cannot hide. We cannot tell it because it is a desire for something that has never actually appeared in our experience. We cannot hide it because our experience is constantly suggesting it, and we betray ourselves like lovers at the mention of a name. . . . All the things that have deeply possessed your soul have been but hints of it—tantalizing glimpses, promises never quite fulfilled, echoes that died away just as they caught your ear.1

If something in the experience of psychedelic drugs had not evoked Sehnsucht, it would not have altered the course of lives or inspired art or triggered a movement. After all, there are more reliable and less complicated drugs for goofing, for partying, for stimulus, or for oblivion than acid. The thing that was new with psychedelic drugs, the new twist they gave to Sehnsucht, was the feeling that they might do the impossible (impossible, it had been thought, in this life): satisfy that most profound desire, bring us to the object of our great longing. In the early nineteenth century, the Romantic poets thought they sensed the near approach of the eternally desired; it had come close in their time; they could feel it (“Great spirits now on earth are sojourning” said Keats). And perhaps in the 1960s it came closer still, the human heart trembling on the razor’s edge, butterfly fragile, awe-fully, unsustainably on the brink of realizing it, so that the songs were shot through with a light from the other side of the summit, from the far side of desire. Perhaps it came that close.

Of course this desired thing is impressed in memory with the smell and noise and flavor of the time. And so the oddest junk from the period’s culture (pulp novels, comic books, album covers, the remembered taste of cheap wine) seems infused with that presence. Over the years since then, we led this beast from the smoke-filled, urine-smelling, OD’ing psychedelic ballrooms into our families’ homes and our children’s bedrooms, until it became finally a household deity, a pixie that in daylight hours lives in boxes of old LPs.

The Dead’s attitude toward their musical tradition was not simply a veneration of roots but an appreciation of roots for the new uses that could be made of them. Unlike the New York folkies, the Dead were not looking to the music for a politically useful past. For them the old music was a place where the profane time of contemporary America opened into story, allowing room for imagination. The old music suggested things to them that that psychedelics affirmed and amplified.

Cultures around the world anchor their identities in sacred texts. Preserved physically or in memory, the texts serve to hold back incursions from the world that could overwhelm their traditions. For marginal American populations, separated by their work, race, religion, geography, or economic status from the larger society, the text was often their music. In the 1950s some young American intellectuals rediscovered this music and thought that they could use it in an analogous way, to resist absorption into the consensus culture. Their attitude toward the old music itself was mostly conservative. They wanted to protect and preserve it—not experiment with it, expand it, or transform it.

People like the young members of the Grateful Dead were the next iteration of this process, and they began to have drug-inflamed notions that they could extend the text and develop it. They would create a new folk music for the frontiers of consciousness. Because, like Bob Dylan, the future that they believed the traditional music implied was not “traditional” at all; rather the music implied and pointed toward a new kind of consciousness, a psychedelic way of seeing. They would move the folk tradition forward with their own original work to help build a culture that could sustain a new, rapidly expanding bohemia against the mass and weight of straight America. Their aim was not conservative but revolutionary and evangelical.

The old mountain song “Cold Rain and Snow” is a blues song that turns into a murder ballad, told from the point of view of a mistreated husband. The Dead, in making it into folk-rock on their first album, ignore the story line and break it up into its component images. In the Dead’s version “Well she’s coming down the stair, combin’ back her yellow hair” is not, as it was in the old song, part of a progress into resentment and murder, but an isolated iconlike image out of a mountain myth. The suggestion is that the culture of the rural poor is not just a record of hard times and exploitation, but sometimes one of visionary beauties too.

By the time they went to record their second album, Anthem of the Sun, elements were falling into place, beginning to form a distinct vision. Anthem vindicates the loose openness to inspiration, the California Zen that was becoming the band’s characteristic approach. The first three tracks (or side one of the LP) are electrifyingly exciting. They show the ambition and the reach of the new San Francisco music at its freshest. When the music of the Haight didn’t work, it lurched from one half-realized idea to another in a distracted haze, satisfied with its own far-outness. But when it worked as it does here, it really was a new kind of rock and roll. You maybe can’t spot the chug of Chuck Berry in a song like “Born Cross-Eyed,” but it bursts with exuberance and momentum just the same; the band is exhilarated by the new free space they’ve found to work in. The apocalyptic playfulness that the Grateful Dead suggested in “The Golden Road” on their first album finds full expression here.

This new space included broad tracts of the unconscious. Large and deep things were elbowing their way into the music, archetypal images and mythic patterns. Those first three tracks of Anthem are a kind of suite that suggests the sacrificial pattern that our culture knows best as the Christ story, beginning in “That’s It for the Other One” with a haunting, nursery-rhyme Calvary: (Garcia: “I think it’s an extension of my own personal symbology for ‘The Man of Constant Sorrow’—the old folk song—which I always thought of as being a sort of Christ parable.”)2

The other day they waited, the sky was dark and faded; solemnly they stated,

“He has to die, you know he has to die.”

And all the children learning, from books that they were burning, every leaf was turning

To watch him die, you know he had to die.

This is followed by a descent into a psychedelic hell and resurrection in a lyrical aubade.

The Dead were getting a purchase on something. They had quickly passed, if they ever even noticed, the stage of simple psychedelic fireworks. Before long, their trips were taking them near to the rattling engine house of the cosmos, Allen Ginsberg’s “starry dynamo,” the generator of images and myths. They began to develop a recognizable sensibility, greatly aided by lyricist Robert Hunter, a kaleidoscopic jumble of myth and story that included not only mystery and wonder but also a sort of weathered cosmic humor. This sense would flavor all the rest of their work, no matter what musical styles they passed through. The Dead’s psychedelic world, I would maintain, is as rich as the infernally glowing carnival world of Blonde on Blonde. They both have an immediately recognizable savor, a style of rambling parabolic narrative in an America that’s half recognizable as home, and half a province of the Great Beyond.

For the Dead the tone was largely set by Jerry Garcia’s style of guitar playing, and that style was a kind of poignant psychedelic lyricism. It probably had its origins in certain haunting turns of melody in old British and Appalachian songs. But Garcia’s gift was to retain this quality without referring to the past, to apply it to the present and an idea of the future—in other words, to make it Californian (indeed you could hear that there was a little trebly surf guitar in its origins).

There was also an elusive evocative quality to the Dead’s sixties music. It was elusive because it was not exactly evocative of the past, like traditional folk music. You could say it was evocative of the future. Not a science-fiction technological future, but a mythic future. The notion that the future was going to be as haunting and compelling as the mythology of the past, that the future was going to be the myths realized. The Dead’s achievement was not on the scale of William Blake’s, but there was a Blakean sense to it that it was the stirring of ancient energies that were creating the revolutionary present. The New Age is in some ways a very old idea.

Fig. 6.2. The Dead's trips took them into the mythic realm.

In the working title of their third album, the Dead gave this new territory of theirs a name—“earthquake country,” tales from an unstable frontier zone that was as unmistakably the Dead’s imaginative homeland as Penny Lane was the Beatles’. By the time of its release the title had become the palindromic Aoxomoxoa. Recorded from September 1968 to March 1969, Aoxomoxoa is one of the definitive expressions of the psychedelic imagination, of the Dead’s ability beyond other musicians of the time to depict what happens to the image-making function of the mind in the psychedelic experience. And they accomplished this not through long trance-inducing jams and studio effects but through the medium, mostly, of concise and satisfying—sometimes even rocking—songs.

“I don’t even like to remember how far out we were when we were working on that album,” a member of their coterie said later. But for all the tripped-outness that may have been involved in the making of Aoxomoxoa, it is (with one glaring exception) a rather tightly assembled and cleanly produced record. There are moments when it weaves woozily near the cliff edge, but it never finally leaves the rails. In fact, on Aoxomoxoa the Dead build that swerve-and-rescue into their own way to rock—that’s the basis of its exhilaration.

Aoxomoxoa is a little scary, or if it doesn’t unsettle you a bit, you may not really be getting the vibe. Everything about Aoxomoxoa—every sound, every sung syllable—really feels as if it is comes from a sensibility that is very, very high. So high that you might not even notice it at first, the environment is so total. There’s no random “freakiness,” no jarring juxtapositions, because they’ve imagined a world down to its smallest parts that reflects the condition of their consciousness. It’s a place where the littlest thing drips and trembles with implied hallucination, as if you have to move very carefully to keep objects from flying away or bursting into droplets when you brush them. Everything winks at you with acid mutability the way that everything is instinct with menace in the House of Usher. It’s a place where it is hard to judge whether you’re dreaming or not. But the product of this derangement, as with Rimbaud, is in the end not terror, but beauty. That is the Dead’s acid benignity, their faith. But you have to risk the terror to get there. If they are not in the chamber where dreams and myth are generated, they are only one or two doors down. Though they spend much of the rest of their career singing Americana, it will be an Americana whose every note contains an echo of this place. That’s what will make a lot of it great.

You will notice before long that the Dead seem to completely have their sea legs here. They have not gotten lost and wandered into earthquake country, or been abducted into it. They have been working toward this place for some time, and they move here with ease. They are the house band in this world, like they were at Ken Kesey’s place.

Some of these songs may slip by you in deceptive normalcy. “Dupree’s Diamond Blues” harks back to their jug-band days, an amiably goofy yarn that seems to have things in common with the Lovin’ Spoonful. But, really, if you have friends who have never heard some of these songs, I would first try playing them something like “China Cat Sunflower” and see if the euphoric disorientation of hearing a band getting down and flying apart at the same time, the psychedelic geniality, the glorious mayhem, doesn’t prove appealing. The players weave in and out yet still somehow cooperate to propel the irresistible shuffle forward. You’re so absorbed in trying to track what everyone is doing that you almost don’t notice until midway through that you’ve been snagged in an eccentric but powerful momentum and that, without you really noticing, the Dead have shifted gears from shuffling to steaming, and you lift up your head and say something predictably like “wow.” There is something quixotic about it, absurd yet sort of noble, the musical expression of all the addled hopes for a psychedelic reformation, a song for a stoned crusade whose banners are tropical birds, but with some of the force of an army nonetheless.

The playing on Aoxomoxoa is beautiful, often delicate—the Dead never played so well in the studio, before or after. The lyrics are a torrent of flashing images that catch the light for an instant then are gone under the surface again: “St. Stephen with a rose / In and out of the garden he goes”; “Hey the laurel / Hey the city in the rain, / Hey the white wheat / Waving in the wind”; “Wash your lonely feet in the river in the morning”; “Wrap the babe in scarlet colors; call it your own.” Sometimes the images come in a hectic rush, piling one on top of the other:

I rang a silent bell

beneath a shower of pearls

in the eagle wing palace

of the Queen Chinee

There’s an archaic note in the mix of Aoxomoxoa, as if the Dead, shock troops of the West Coast future, were reaching back past even the Appalachians, finding a connection between earthquake country and the Debatable Lands of the Scottish border. Songs like “St. Stephen,” “Rosemary,” “Mountains of the Moon” feel like jumbled Child Ballads. Or maybe it’s not the historical past the Dead are looking to connect with, but the personal past, the world of childhood. A lot of Aoxomoxoa has to do with the child’s world—the colors of earthquake country are vivid and bold, its characters outlandish, its words like nursery rhymes: “Is it all fall down, is it all go under?”

If you live intimately with these songs for a long time, a funny thing happens to your aesthetic sense. When you encounter myth, fantasy, or folklore in other places—in literature, drama, painting—your experience of it is changed. The Dead have brought you so far into the psychic kitchen where these things are cooked up that The Arabian Nights or the Brothers Grimm forever after have an atmosphere from earthquake country about them, a lingering smell of ozone. They will give you the secret signal you learned on Aoxomoxoa: there will be a wink and a shock of recognition. The stories no longer lie so reliably on the page. There is some anxiety that, when you’re not looking, they might force their way across the threshold between imagination and waking life. The achieving of this atmosphere, I think we can say now, is real mythopoeia, in its 1960s form, and may be the Dead’s biggest accomplishment—the feeling that a strange new energy was entering the present and galvanizing all the old visions back to a dangerous life that we had thought safely sealed in historical amber.

Unless . . . unless you think the vision is compromised by the method. Because after all, the Dead’s way into this world was not through a spiritual practice, nor an imaginative exercise, nor the poetic temperament. It was acid. The Dead can’t be seriously talked about without talking about acid. And how we think about acid affects—ought to affect—how we think about the Dead. If acid is just another high, then the Dead were the hippie Dean Martins, stumbling around clutching their tabs of Owsley orange sunshine the way Dino held on to his highball glass. Comically dissipated figures from a bygone era, with their hipness become kitsch—indeed, this is how they were seen by many in the later stages of their career.

The argument that started practically from the invention of LSD is about whether or not psychedelics provide legitimate spiritual experience. This argument feels a little musty today, fifty years further into postmodernity, implying as it does that there is some test for distinguishing authentic from artificial spiritual experiences. Today we would be inclined to say instead that spiritual experience is whatever is perceived as spiritual experience by the person having it.

And yet there’s still something funny about lysergic acid. There are the rather astonishing results that have been gotten from the therapeutic use of psychedelics with depression and other forms of mental illness, with addiction, prison recidivism, the anxiety and sorrow of the dying. There is the growing importance of the role that anthropologists and historians are seeing for the use of psychedelics and other ecstatic techniques in early human cultures and in the whole question of the origin of religion. The degree to which the effect of psychedelics is distinct qualitatively from that of other mood-altering substances is a problem in the contemporary debates over consciousness. There is something about the particular type of experience facilitated by these drugs that seems to be not just a matter of culturally constructed interpretation; that is, they fairly dependably produce experiences, across a great diversity of human subjects that are felt to be inherently value—and meaning—laden. Half a century on, acid is still a secret staircase that lets ghosts into the neurological machine.

Acid culture, the culture of the Haight, of which the Dead were perhaps the most famous proponents, gave the heirs of mainline Protestantism an injection of interiority like they hadn’t had since the Romantic era, a capacity to sense and describe inner states and processes that had previously been the shoptalk of poets, heretics, psychoanalysts, and monastics. African American religious leaders and their followers could speak with compelling authenticity about the actions of the Holy Spirit because they had actually experienced ecstasy and worked with it. It’s what gave the rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement much of its prophetic resonance. White civilization, on the other hand, had long since traded any techniques of ecstasy that European people may once have known in exchange for technological competence. Now psychedelics gave white people the means to speak with familiarity about the dynamics of the inner life, and this spread even to people who had never taken acid, maybe never even smoked dope. One way of describing the difference in Western life between pre-sixties and post-sixties is that the spiritual life became a fact of human nature that (like sex, and at about the same time) had to be generally acknowledged instead of occasionally, discreetly referenced.

To base a critique of society on a tradition of ecstatic experience was, as we’ve seen and will see again, a time-tested strategy of the underground. The difference in the 1960s was that this kind of critique was eventually picked up by a significant section of the dominant culture. In some ways this change of consciousness would be durable and deep; in many ways it was febrile, unstable, and superficial. One can imagine other ways it might have happened—maybe the early acid evangelists’ idea of turning on an influential elite (“thought leaders” we would say today) and letting it filter down through the culture would have effected this reformation better than tossing it to the kids in the psychedelic ballrooms. The Internet, digital technology, and social media, many of whose pioneers were directly or indirectly products of the culture of the Haight, are both a panicked stampede away from this mode of consciousness and at the same time an obsessive attempt to literalize the themes of acid culture—the access to knowledge, the connectedness, the personal autonomy, the devolution of the power to create—in all these things and more the digital revolution has tried to literalize psychedelic metaphysics.

A successful Grateful Dead performance acted out musically the central practice of acid culture: let the old forms melt away and keep loose and improvise until a new structure closer to the truth emerges—which is as good a description as any of the point of life in the Haight in the mid-1960s, in the narrow window of time when it really was a huge spiritual experiment. This is one recognized method for truth seeking (it is Blake’s road of excess and the core of alchemy) though a hard one—not everyone will make it through to the other side of dissolution. But this was why the kids were coming. This is what they were hearing in the music. This is why the young girls were coming to the canyon and why the Rivieras were hurtling west from Indiana. And this indeed, irregularly, and sometimes at a very high price, was accomplished.

Fig. 6.3. Haight-Ashbury street signs (photo by Tobias Kleinlercher)

But as far as the Grateful Dead were concerned, the ecstasy—what had once been a deep enchantment, a gracious crack in the world through which another world might be seen—eventually became rote, an empty ritual. The sixties has its share of sad lessons, and this is one of them, no doubt rehearsed throughout the history of religions but acted out emblematically in our slot of time by rock-and-roll bands. And none of the stories, not even the careers of ex-Beatles, are really sadder than the Dead’s, because the Dead were held to be experts in magic, purveyors of not just music but transport. As individuals, they were mostly too good to deliberately trade on this reputation, to commodify it. They never promised or guaranteed transport. They always said they were just a rock-and-roll band. Yet their camp followers, the Deadheads, were their shadow. The Deadheads (their name was grimly apt) were the tribe that did not—would not—learn the sad lesson. The Deadheads believed that transport could be delivered to them on demand, and they were living proof that the Dead had not adequately taught the lesson, the cosmic tragic contradiction between the apparent human imperative to cultivate ecstasy, and the apparent truth that ecstasy cannot be dependably cultivated. It’s what you do after you learn the sad lesson that makes all the difference.

The Dead lived and died by the jam, their trademark resort to aimless improvisatory interludes. Even in their heyday the jams only intermittently led anywhere fun or interesting, and eventually it became clear that they were largely aimed at the most inertly and uncritically stoned in the audience. It was amazing how fast this avant-garde style came to seem so tired. And so it is surprising today that some—some— of the jams turn out to be beautiful if you suppress your instinctive post-sixties reflex to shut that stoner noise off! In the “Not Fade Away”/ “Goin’ Down the Road” medley on Skull and Roses, one song flows into the other with the naturalness of a creek in its course and leaves you reassured and refreshed.

One had time over the years to get heartily tired of the laid-back shuffle with which the Dead seemed to interpret every variety of American music. But I think, to give them the benefit of the doubt, what they were sometimes doing was being gentle, careful, with these old songs, songs like “I Know You Rider” and “Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad,” as if carrying something fragile and valuable. They let the emotional momentum of the songs build itself, letting the songs have their own mighty say. Garcia’s leads with their floral generosity, those curlicued lines of silver filament, provided the setting for the jewel in the song. In many ways the Dead had fallen away from the vision they pursued in the beginning, yet they held these occasional moments tenderly, knowing them for what they were.

In 1934 the father and son musicologists, John and Alan Lomax, in a song-hunting expedition in the American South (maybe in Texas, they never said) met an eighteen-year-old black girl who was in prison for murder, marginal in almost every way she could be.

Her name and the particular prison she was in are lost, but that is hardly true of the song she sang them that day. The Lomaxes, in American Ballads and Folk Songs, called it “Woman Blue.” It’s better known as “I Know You Rider,” a folk and rock staple since the 1950s, and a song that never left the Dead’s set, from the days when they were still known as the Warlocks to their final dissolution. For over thirty years they kept returning to it.

The Lomaxes were typical of folk-song collectors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in that they seemingly could not keep themselves from fiddling with the material they collected. Alan Lomax himself admitted that the girl had given them only the chorus and one stanza, and that he imported some verses from other blues fragments they had gathered, so the lyrics are doubly anonymous.

But the funny thing is how, as you listen to the Dead perform “Rider,” you could so easily imagine this as a Grateful Dead original, one of Robert Hunter’s finest lyrics. Because the words have the visionary American lyricism, the place where the cosmic and the colloquial connect, that Garcia and Hunter liked so much:

I know my baby sure is bound to love me some

I know my baby sure is bound to love me some

Cause he throws his arms around me like a circle around the sun

I laid down last night Lord I could not take my rest

I laid down last night Lord I could not take my rest

My mind kept rambling like the wild geese in the West

Sun gonna shine in my back yard some day

Sun gonna shine in my back yard some day

And the wind gonna rise up baby blow my blues away

The imprisoned girl knew how to read the book of nature. The three images—the sun, the wild geese, the wind (the cosmos, the animals, the weather)—identify her with the great world. With her lover, she is like the sun in the middle of the planets; without her lover, her mind is like the wild geese flying west; and in the end her blues will be blown away not by her own action but by the greater action of the wind.

So the Dead went back from time to time to restate their place in the transmission of American vision. And then, just to show how it goes on and keeps working, they added their own last verse:

I wish I was a headlight on a northbound train

I wish I was a headlight on a northbound train

I’ d shine my light through the cool Colorado rain

And a small shiver of strangeness peculiar to the Dead enters the process, a touch of psychedelic transformation (the merging of the seer and the seen), their tint to color this artifact that had so many hands in it.

As the years went by, one was distantly aware that the Dead continued to traipse back and forth across the land. I never bought another Grateful Dead album after 1971’s Skull and Roses and I never wittingly listened to another Grateful Dead studio album—the story was too dire. But I heard enough at parties and on the radio—especially bits from the bottomless arcana of their live bootlegs—to know that occasionally a rose-tinted presence would come over the weary shuffle, and then the old new world would be present again. It didn’t belong to the men on the stage anymore—it had never really belonged to them—it was just grace, but they weren’t strangers to it either. The Merry Pranksters’ “unspoken thing” had long since gone back into hiding, and eventually there were other better places to look for it. But back in 1969 a lot of the people who were most seriously in pursuit of it—all the “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night”—knew that they should be listening very carefully to the Grateful Dead.3