10

THE PROVERBS OF HELL

The Journey of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground

Oh Wilde, Verlaine, and Baudelaire,

their lips were wet with wine,

Oh poseur, pimp, and libertine!

Oh cynic, sot, and swine!

Oh votaries of velvet vice! . . .

Oh gods of light divine.

ROBERT SERVICE

TO TALK about Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, it’s useful, even necessary, to resurrect an idea that has almost fallen out of polite discourse—the idea of the perverse.

To say someone is a pervert is like saying someone is a cripple. Such language is always crude (and always at least rhetorically violent) because it nails the fullness of a person to a quality. To say someone is perverse, however, is different. The threatening noun becomes an almost playful adjective. Perversity is a quality of character, a quality that can be maddening, but also often points the way to things of great interest that are not obvious to the non-perverse.

The charge of the Velvet Underground’s art comes from its perversity: “the fruitful movement against nature,”1 as C. S. Lewis says; the willful choosing of the option that goes against the straight, the whole, the natural, the healthy; preferring nothing to something.

The sharp edge of the perverse can be a useful tool for chipping away at accretions that form around the truth. Whenever a philosophy, a religion, or a society becomes too contented, too sure of what it knows, too easily happy, too dull, it needs the perverse. Wisdom is taught by means of the perverse: At some point we all need to hear the proverbs of hell, as William Blake called them. You notice that holy people seem to enjoy scandalizing good people with the perverse. In Jesus’s parables he seems to take a perverse delight in turning the normal, sensible understanding of his listeners upside down. God knows that Zen monks and Sufi jesters seem to relish pulling the rug out from under the expectations of the decent people they meet. Perversity is the reverse of the way that the world goes, by no means a necessarily bad thing.

The four albums that the Velvet Underground released from 1967 through 1970 are a document of how negation, the passage against nature, away from the light, the choosing of nothing over something comes, if followed through the whole cycle, to an unexpected—a perverse—conclusion. “Down for you is up,” Lou Reed says in “Pale Blue Eyes.” The records document how that works.

There’s a process in the four studio albums that is not just the chronicle of the growth and development of a band. They seem to have been thought through in advance as if they had been conceived as a kind of confession or bildungsroman. With other bands, the Beatles or the Stones being the classic examples, there is a steady linear chronological progress—they become capable of more musically, their themes become more self-conscious—but it is not a story. But the Velvets were never not highly self-conscious. They were perhaps the first rock band to have no unselfconscious, naïve origins. The Velvets’ first album came out in 1967. The various ideas for the artistic organization of pop music—the concept album, the rock opera, the double album, the acoustic side and the electric side—were in their heyday. Given that the concept album was a primary datum for them, it’s not a long step to imagining a concept cycle of albums.

What is the design? For surfacing in such a ferociously avant-garde scene, the tale the Velvets tell is really quite basic—primal even. It might have been one of the first dances around the fire. It is the wheel of fortune: down and up, descent/rise, exile/return, destruction/integration. It’s part of the structure of consciousness, a pattern so ingrained that it is almost impossible not to use it to interpret the events of life.

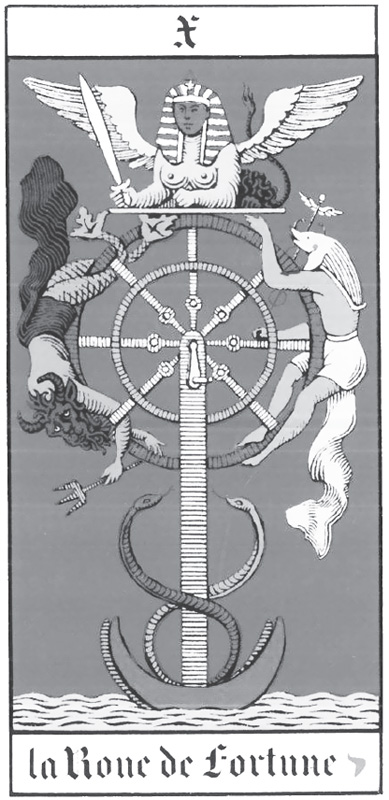

To the reasonable eye, up and down are opposites. But the paradox of the wheel of fortune is that they’re not; they’re one movement. That’s the perverse vision. “Down for you is up.” The people who played the game of tarot knew that falling as far as you can becomes the same thing as rising.

The Velvet Underground was walking an elemental path as much as the Grateful Dead, only there were to be no mythic gewgaws attached to the Velvets’ version. The Velvets meet no wizards or fairies or gods along the way. Only the skeleton of the narrative was to be retained, the framework that remained after dipping in the corrosives of Andy Warhol’s Factory.

There is an old idea that a full cycle, or any complete thing, is made of four phases: the four seasons of the year; the cardinal points of the compass; the four elements: air, earth, water, fire; the levels of the universe: Earth, Hell, Purgatory, Heaven; the four stages of alchemy. The four Velvet Underground albums—The Velvet Underground and Nico, White Light/White Heat, The Velvet Underground, and Loaded— make a full cycle. There is an intuitive movement from one to the other. Each album is marked by a distinct mood, feeling, and a wildly different idea about sound. While there is an ongoing consistency of voice and personality, mostly because of the presence of singer, songwriter, and guitarist Lou Reed, the feel and approach of each successive record drastically, almost mischievously—perversely—undercuts the expectations created by the previous album. Lou Reed of course could simply be playing “head games” in a hippie trickster mode. But if there’s more to it than that—and I think there clearly is—then there must be something else being expressed, four different ways of feeling and seeing, four variations; a progress toward an idea of completeness.

And, as I’ve said, it’s not an evolution from musical primitives to sophisticates. That kind of development happens almost unconsciously, and it’s a factor of time and experience, hours logged, dues paid. The Velvets weren’t temperamentally dues payers. Reed, at the beginning, is already a formidable lyricist and songwriter—“Heroin” and “I’ll Be Your Mirror” tell you that. John Cale—electric viola, bass, keyboards—was one of John Cage’s collaborators. He was part of the Manhattan musical avant-garde before he ever became a rocker. The Velvets didn’t develop an artistic credo; they began with one, one that was easily capable of thinking about an entire career as an art project, about sequencing a career like sequencing cuts on an album.

For the Velvets, the experiment was in a way to become less sophisticated, not more. (It’s in this way—a group of hip urbanites consciously pursuing a kind of primitivism—that the Velvets are the pre-figurers of punk that they are always said to be.) This movement was reinforced by the departure halfway through of Cale, the most theoretically sophisticated member. The Velvets are less avant-garde as their career goes on. This is not a natural process; it’s an artificial, a perverse process. The metaphor is not organic growth, but artistic fashioning.

So now it’s probably time to lay my cards on the table and say what I think the story is. Here (apologies to Joseph Campbell and Northrop Frye) is the Velvet Underground’s version of the monomyth:

- The Velvet Underground and Nico: Contention for the soul of the hero.

- White Light/White Heat: The hero surrenders to death and negation. He descends into the demonic world.

- The Velvet Underground: The hero’s purgation/purification.

- Loaded: The hero is reintegrated into the World.

The Velvet Underground and Nico, released in March, 1967, sets out the hero’s predicament. There are two warring impulses in him: on one side the attraction of extinction, of absurdity, a cold purity, cruelty; on the other the instinct toward light and compassion. The two impulses are woven through the songs on this record; each one could be the death of the other.

“Sunday Morning” is the first we ever hear from the Velvet Underground, and it begins with bells. They’re not the chimes of freedom; they’re indoor bells, nursery bells, their prettiness perilously, almost campily fragile. These little bells couldn’t possibly survive some of the places we’re going to visit. So there is dread inside the delicacy, and throughout the song a strange frosty aural penumbra surrounds everything, the sound of an empty space echoing back what you just said. “It’s just the wasted years so close behind.” The singer would drop this self in a heartbeat if he knew how (we can see ahead to “Heroin,” where he learns how). “There’s always someone around you who will call, ‘It’s nothing at all.’” And that message is the singer’s worst intuition, that “it”—life, the world, existence—is nothing at all. But it also calls to his perversity. In the Velvets’ world the call of the perverse masquerades in all kinds of sexual grotesquerie, but when you get to the bottom it’s mostly about extinction.

And as soon as the bells fade, in a piece of classic Velvets perversity, their memory is ground into the pavement by the remorseless hammering piano chords that open “I’m Waiting for the Man.” From the nursery to the street. Sunday mornings past, the hero goes uptown to score. What is the sense of the rough transition? He goes to score because he can’t stand the sense of how fragile the bells are compared to his elephantine dread.

“I’m Waiting for the Man” is great rock and roll because it lashes itself tight to one function of rock and roll—the potential for trance induction via the strictest repetition. In a very early interview, Lou Reed set out his artistic manifesto in five words: “Repetition—it’s so fantastic. Anti-glop.” “Waiting For the Man” is that manifesto in practice. There’s so little to listen to that your attention narrows dramatically to what is actually happening—the relentless repetition of the few chords—until you begin to notice subtle differences in the up and down strikes on the strings, little flourishes, and when you do you’ve come through to a new exhilaration, the beginning of trance. But the point is, unlike many other would-be rock artists, they keep the fun. And that’s Reed’s business. Reed wants to bust out, and Cale keeps him laced tight, and the result is tremendous excitement. And so it comes back around to where it started—the nightmare amplification of the uptight tapping of a Cuban heel on the uptown sidewalk.

“I’m going to try to nullify my life,” the hero sings at the beginning of “Heroin.” It might be a man addressing the needle, or it might be a mystic addressing God, and there’s the scandal that engenders the Velvet Underground’s art. No, the junkie and the mystic don’t really want the same thing in the end, but maybe the annihilation of self-consciousness is as basic an instinct as survival. The Velvets don’t draw conclusions—they just vividly evoke the hero’s eros for light and his eros for extinction. The deathly frantic lust of the rush alternates with the interludes, attention centered on the drone, of peace and sweet yearning.

The drone that runs through “Heroin”—that high, pure, unchanging note, beautiful but nonhuman—is both the call of oblivion, the peace of the drug, and also the song of the spirit. It’s why the song is both dreadful and exhilarating, even inspiring. There is the black delight in the rush, which laughs to throw life and the world away (with the implication that the judgment of the junkie against all of life may be a valid judgment). And there’s also the beautiful pure yearning:

I wish that

I’ d sailed the darkened seas

on a great big clipper ship,

going from this land here to that . . .

And there’s wonderful compassion on this record. “I’ll Be Your Mirror”—written by Reed, sung by German chanteuse and Warhol superstar Nico—is a song to a person who is convinced that they are irredeemably twisted, a deviate who must not be taken out of the dark. The singer pledges that she will be the sign of his beauty, his mirror. This reassurance comes out of a great depth of quiet, a little like a parent reassuring a frightened child, only these are not innocent people, these are people whose history, they think, puts them outside of the light, who have long since internalized the terror of what the light may reveal about them. The love is almost abstract; you don’t feel a personality behind it as much as you do the pure benevolence. These compassionate moments of The Velvet Underground and Nico are terribly delicate, like those first bells. It is one of this era’s loveliest love songs.

If on the first album the two apparently opposite impulses are contending for the soul of the protagonist, the tone of the second album, White Light/White Heat, is set by the black-on-black image on the cover of the album. The hero has despaired of separating the two impulses and steps off the edge of the pit. On The Velvet Underground and Nico, the drug metaphor for transcendence was the opioid peace; here the metaphor is the white light, the glare of the amphetamine rush. It is a hard and mean album. The shiny black of the cover is the sheen of the music. You’ll look—almost—in vain for a ray of compassion. Northrop Frye talked about how in the classic structure of romance, the hero must descend from the human world into the demonic world. In the Velvets’ cycle, White Light/White Heat is that passage.2

There are six songs on White Light/White Heat: one is about shooting up methamphetamine; one is (apparently) about talking to a madwoman’s ghost; one is about some sort of sexual surgery; one is a long, stoned recitation of a puerile gag from Lou Reed’s college days; one is a darkly lyrical fragment built on an adolescent double entendre; and one is seventeen minutes of brutally assaultive but strangely catchy noise, narrating a story of murder in a Last Exit to Brooklyn congeries of transvestites and dealers. In his solo career Reed would go back to exploit the tawdry transgressiveness of this métier (which I think was partly a kind of joke in the first place) to titillate audiences of college kids. But the joke here is admittedly taken pretty far, far enough, anyway, to suggest what feels like a genuine bad vibe. There’s something convincing about it in the end. The scenarios may or may not be authentic, but the urge to violate feels real.

Since the Velvet Underground’s day, other bands have worked with the intentionally crude and discordant, but few as effectively as the Velvets on this record. Sooner or later the crudity of other bands usually reveals itself as a new kind of groove, that is, a musical impulse ultimately subsumes the nihilist impulse. That eventually happens with some of this music, but it demands a special kind of resolve from the listener. The first impression—that they had really torn through the long taboo against ugliness for its own sake—is strong.

Through a lot of the Velvets’ music there is a perverse asceticism, a masochistic desire to impose the most remorseless strictures on themselves and their listeners, to refuse at every point the option of easy pleasure, to only accept beauty if it is completely stripped of ease or sentiment. The consistent choice of the discordant and incomplete, of even an accidental grace note, bespeaks either genuine unconcern, or a kind of discipline. There is something pure and elemental in the sound’s implacability. It may be a last-ditch defense of beauty and pleasure, or it may be the lust to administer a final stomping.

But somewhere in this dance of aesthetic maneuvers, there is a groove, and the band finds it. The perverse method generates two fine rock-and-roll songs: “White Light/White Heat,” the one about shooting up methamphetamine, and “I Heard Her Call My Name,” which, as noted above, is about talking to the dead. Although sometimes they don’t feel so much like whole, contained songs as pieces of the furious froth tossed off by the album. (In fact this appearance is misleading—they have more structure than is first apparent. The soundtrack of the movie Lawless includes a performance of “White Light/White Heat,” recast as a moonshiner’s anthem, by the venerable bluegrass musician Ralph Stanley, and it’s a gas to see how it works with perfect natural-ness. This structural traditionalism of the Velvet Underground would soon become much more apparent.)

And “Sister Ray” is maybe a fragment of a great rock-and-roll song, obnoxiously extended. Even here there’s something kind of catchy, a stray bit of pop surfaces in the grind, the Archies as anomic sociopaths, some echo of the Pickwick Records songwriters’ bullpen where Lou Reed learned his craft. There’s a kind of Teutonic perkiness that first grabs you, then frog-marches you through the rest of the seventeen minutes. It’s partly descended from the nasty delirium of the Kingsmen’s “Louie, Louie,” only this time with unambiguous dirty words.

“It’s aggressive, yes. But it’s not aggressive-bad. This is aggressive, going to God,” Lou Reed insisted to David Fricke, talking about White Light/White Heat. When Reed says, “I’m searching for my mainline” in “Sister Ray,” it’s the whole Velvet Underground method in a fragment. He’s clearly talking about shooting up; just as clearly he must have been aware that the words are going to evoke spiritual associations. This double sense is rarely absent from the Velvets’ music; it seems to come out unconsciously. It’s the same with the name of the title song: “White light” is the goal of the seeking hippie, the intense purification of attention that leads to bliss, and it is also the moment of the speed rush. Here in the pit, ecstatic oblivion and God are together at a place so primitive they can’t be easily distinguished.

Then something happened, the kind of thing that makes the story of the Velvet Underground so incomparably interesting.

But let’s take a moment here. The conflict in the protagonist of the Velvet Underground cycle is not primarily—although I may have made it seem so—a conflict between drugs and the soul, between God and bad habits. Rather, it’s between the cold and the compassionate heart. Lou Reed, ironically, is a confessional writer, like Joni Mitchell or Jackson Browne. Reed’s use of his recorded persona is complicated, but there is clearly some degree of identification between Lou Reed, b. 1942, Brooklyn, New York, and “Lou Reed” the hero of the Velvet Underground cycle. And “Lou Reed” can be one cold motherfucker. “Lou Reed,” a lot of the time, finds other peoples’ afflictions funny, and funny in a spiteful adolescent way. Lou Reed/“Lou Reed” has a stupid nihilistic laugh, like the way he laughs when he sings “They hit her harder, harder, harder” in “Foggy Notion.” But Lou Reed at the same time is an artist capable of extraordinary expressions of tenderness, one of the great poets of kindness in popular song. That’s the struggle that begins to make this music great, a struggle between some kind of very convincing ugliness, and a sublime gift of compassion.

My point here is, if we don’t acknowledge that there was a black cold place in Lou Reed, that there was a real conflict, a real risk of losing his soul, then, as Charles Dickens says, nothing marvelous can come of this tale. And something marvelous does.

Because the album that followed White Light/White Heat a year later, The Velvet Underground, is one of the most striking transformations in an era famous for striking transformations. More abrupt than Dylan going electric, more suggestive than the Grateful Dead going from “What’s Become of the Baby?” to “Uncle John’s Band,” as strange as the Beatles going from “P.S. I Love You” to “A Day in the Life,” was the Velvets’ one-album odyssey from “Sister Ray” to “Jesus.” The sudden delicacy is as shocking in its way as any outrage they had previously offered. At first it almost seemed as if it might be some sort of Warholesque poker-faced prank. But here you begin to see how the story is moving. The Velvet Underground is clearly meant to be received in the context of the preceding record. It’s making a point that could only be made in contrast to the previous music.

The cover of the album is a grainy black and white of the band caught in a camera flash (the white light again) sitting on a couch at the Factory. A little space of light: without it the cover would again be all black, just like the previous one. On the back of the album are two identical half images of Reed, mirror images (the mirror again), one right side up, the other upside down. Lost twins, reunited. Or two selves pointing two different ways. Inverse, reverse, and perverse, like the man says.

No one has ever mistaken the story that’s told on this record for a literal conversion. Lou Reed remained Lou Reed; he wasn’t looking for revelation as a way out from under the world’s perversity. But with this record it becomes clear that Lou Reed is working his way to vision.

Something big has happened to him—he tells us that he’s attained the era’s goal, he’s seen the light—but the light doesn’t erase the shadows and strangeness. This isn’t a light that blasts the personality away. It doesn’t flood through the Velvet Underground world, straightening out the kinks. It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah, as another great Jewish-mystic pop artist says.

It’s very still within this record, a gray morning in a quiet cloister of the mind, a Sunday morning. Something strong has come over the music and hushed it. A large part of the album is Reed trying to communicate the experience of that power. In the trio of songs, “I’m Set Free,” “Jesus,” and “Beginning to See the Light,” he does what he can—“Let me tell you people, what I’ve found.” he says in “I’m Set Free.” As Lester Bangs noted at the time, the Velvets had never sounded more like the Byrds; the guitars have a hint of the chime, but restrained, the full ring damped down, an impression of great feeling held back. Lyrically there are echoes of “Amazing Grace”: “I’ve been blinded but now I can see.” When Reed turns into the chorus—“And now . . . I’m set free”—it may be the most straightforwardly heartfelt singing he ever does. But this is the Velvet Underground, so there are things that break up the reverential mood—“I saw my head laughing, rolling on the ground,” Reed recalls from his ecstasy. And after every stirring chorus comes the perverse sting: “I’m set free—to find a new illusion.” The illumination isn’t forever; it will need to happen over and over.

Both the old perverse vision and the newfound vision of love subvert the world. They both take lightly the things that the world considers to be weighty and serious. One is just on the other side of the wall from the other. The giddy song “Beginning to See the Light” is about the hilarity of seeing how easy it is to pass back and forth through that wall.

What is consistent with the previous records is severity—the nonessential is refined away, as on White Light/White Heat, but what’s left isn’t nothing or blackness; it’s a kind of beauty.

If I could make the world as pure

And strange as what I see

I’ d put you in the mirror

I put in front of me

The severity creates a strange lyricism not only in the words but in the playing. The sound of the “pure and strange” is best heard in the one cut (atypical of this record by being a rocker) “What Goes On,” the track they chose for the single. The folk-rock style had been a part of the Velvets’ music from the beginning but had become pronounced with the addition of Doug Yule as John Cale’s replacement after White Light/White Heat. Folk-rock as a sound is haunted by a high bright hum that the music seems to be aspiring toward, sometimes only implied, a potential sound that promises to resolve everything. In California the Byrds came perhaps nearest to realizing the sound in Roger McGuinn’s concluding solo in “Fifth Dimension.” The Velvets got it on tape in Reed’s solo in “What Goes On.” What the two solos share is a deeply moving sense of resolution, the suggestions of an answer to the heart’s desire.

Moe Tucker explains the otherworldly sound of this guitar break by recalling how Reed laid down three takes of his solo, couldn’t choose a favorite, and in the spirit of the times the band suggested that he keep all three, layering one over another.3

Fine as far as it goes, but that’s just the scientific explanation. Never before or since have I heard guitars that sound like this and I’m content to leave it a mystery, but they sound like the high horns of an ancient people racing toward the unimaginable fields of their ancestors. Or shall we call on C. S. Lewis again? “Pure ‘Northernness’ engulfed me: a vision of huge, clear spaces hanging above the Atlantic in the endless twilight of Northern summer, remoteness, severity. . . . I knew that I had met this before, long, long ago. . . .”4

All the dreadful antinomian will to break through, to transgress, to go too far that you hear in the guitar solo in “I Heard Her Call My Name” is still there; it keeps the fierce will, but it’s redeemed: It sends the spirit out through the breach that perversity blasted. The three lead lines weave in and out of each other, never stable, but their direction is resolution and a kind of raging peace. Aggressive going to God, like the man said.

“Jesus” is the song that startled people the most on this album. Lou Reed would not be the first decadent to swerve toward the Cross, but “Jesus” is not exactly a conversion, a capitulation to a ready-made structure of belief. But neither is it ironic, a campy put-on like “I Found a Reason,” the Velvets’ sticky doo-wop love song. Some people might have thought that initially, but it’s hard to find the snicker in it.

Jesus, help me find my proper place

Jesus help me find my proper place

Help me in my weakness

For I’ve fallen out of grace

So it’s come to prayers, people thought. Well, well. In the middle of a record that is dotted with suggestions of religious experience—“I’m set free,” “I’m beginning to see the light,” “I was blinded but now I can see”—“Jesus” ups the ante considerably by adopting a specifically Christian vocabulary. The other spiritual tropes are broad enough to slip by, but “weakness” and “grace” and “Jesus” trigger alarms. And Reed and Doug Yule don’t just deliver it straight, they deliver it beautifully, compellingly. He surely “means” this as much as he means “Pale Blue Eyes,” which he sings with the same stricken quiet intimacy.

With “Jesus” we have to move past the false binary (as the grad students say) of whether the singer means it or doesn’t mean it, as if it were either autobiography or some variety of fake.

Yes, Reed is Jewish and no, he probably doesn’t exactly mean this in a formal Christian sense. There was a Catholic tint to the sensibility of Warhol’s Factory circle, starting with Warhol himself, which might have played some role in Reed’s adopting traditional devotional language. But it might help here to think of Jesus psychologically rather than theologically. Carl Jung thought that Jesus was an “archetype of the Self.” Whatever one believed or didn’t believe about the Jesus of the church, Jung thought, Jesus had a special function in the imagination. This Jesus is an image of a larger, complete self that transcends and by transcending reconciles the seemingly irreconcilable elements of the personality. “It seems to me,” said Jung, “that the Holy Spirit’s task is to reconcile and reunite the opposites in the human individual.”5 Should we be surprised that an artist who began his work by depicting parts of his person at mortal odds with each other ends up addressing a symbol of wholeness?

In Reed’s prayer, the selves that were contending from the first album on, perversity and coldness on one hand, compassion on the other, are both addressing “Jesus.” He’s not asking Jesus to rid him of his perversity—it’s the key to his “pure and strange” vision (which, among other things, leads him to conceive of talking to Jesus). But he wishes that the two halves could produce some sort of meaning together, not one triumphant and one erased, so that their work together is creative, so that he can find “a wealth in division.”

The answer to the prayer is what you hear on the Velvet Underground’s fourth and final album, Loaded. “Jesus” doesn’t redeem “Lou Reed” by straightening out the kinks in his world—he brings the kinks into a larger pattern, finding the place where Reed’s perversity connects with all human concern. As one of Lou Reed’s musical heroes once said:

Nobody has to guess

That baby can’t be blessed

Till she finally sees that

She’s like all the rest.

Jesus sends Lou Reed back to rock and roll, and a more accessible kind of rock and roll than the Velvets have ever played. One of the interesting things that the Velvets do on Loaded is to weave the commercial predicament of the band—they needed a hit—into the band’s artistic project. Ellen Willis said “[Loaded] makes explicit that the Velvets’ use of a mass art form was a metaphor for transcendence. . . .”6

Delivering an album “loaded” with hits to the marketing people at Cotillion Records is also an affirmation of his connection to everybody else, despite his perversity, despite his sexual unorthodoxy, despite his status as one of the damned. No, not in spite of, because of, his perversity—his willingness to descend and to accept what he found there, to ride the whole cycle, enables him to see through the false alternatives offered by the world, and to see that apparently irreconcilable things can be resolved or contained in apparently simple things, like a rock-and-roll song: “Despite all the complications / You could just dance to a rock and roll station.”

Loaded affirms all the people who, for the smallest fraction of a moment, thought that they caught a glimpse of a way to be in a rock-and-roll song, something big and true in there with all the inanity and vulgarity, an infinitely small neutrino that contains amazing power.

But why isn’t this a story of the music industry bringing a notorious rebel to heel? Maybe it is, on one level. But as any sub or dom will tell you, submission to the discipline (in this case the discipline of making radio-ready pop songs) opens a paradoxical freedom. “Sweet Jane,” one of the greatest of rock anthems, shows how that works. Of all the “shoulda-been” hits in the history of pop music, this is arguably the most significant, having had in the long run just as much impact as if it had lodged at the top of the charts for months. It is the apotheosis of rock and roll’s three noble chords, performed with the desperation to connect of a group of teenagers making their first record. “Oh woah Baby!” “Jack is in his corset Jane is in her vest”—Reed introduces his heroes like the Lovers in a perverse tarot deck—“And me I’m in a rock and roll band.” It’s still inverse, reverse, and perverse, but he has a place, his “proper place”; he can claim it now. In “Sweet Jane” Reed fashions a defense of love and life out of his negation, a campy ironic affirmation phrased in rejected stereotypes—a defense of women who faint and children who blush and poets who study rules of verse—because camp at its sweetest is a tenderness toward what humans in their sad hopefulness try to fashion out of whatever stuff they have. “And there’s even some evil mothers,” he warns, “who’ll tell you that everything is just dirt”—the weight of this lying in the fact that he of course was one of those evil mothers and might be again someday. But anyone who ever had a heart, Reed says (quoting Burt Bacharach and Hal David), they wouldn’t turn around and break it.

“Oh! Sweet Nuthin’,” which ends the Velvet Underground’s career, is another example of the Velvets’ “folk-rock” style. In it the lost demimondaines from the early songs are called back and they too, like Reed, find a place. After refusing to exempt himself from their fellowship and their fate, Reed has become their intercessor through the strange course of things. Not with the power or desire to absolve them of anything, but to “say a word” for them. Reed just asks that we notice. Like Willy Loman’s wife says, “Attention must finally be paid.” The sensibility that once found something suggestive in placing the saint and the junkie side by side now asks us to consider these who’ve fallen out of the bottom end of bohemia as the “poor in spirit” who in some perverse way may get their own blessing, may get a share of the reward that goes to those who have given up the world. The climactic rave-up is the Velvets doing “church,” bringing down the spirit to seal the blessing. In the Velvets’ first song on record the “nothing at all” is a source of dread and triggers the whole cycle; on their last, sweet nuthin’ is a kind of peace.

In astronomy something is “eccentric” when it deviates from its orbit. But every eccentricity is in fact the first movement toward a new orbit. Every deviation, shooting off at its queer angle, will become a larger circle if allowed to travel through the full cycle. With Loaded the Velvet Underground cycle is complete.

Fig. 10.1. The Wheel of Fortune tarot card

In the work of certain artists, toward the end, there sometimes comes a generous comic-cosmic vision, like in Shakespeare’s late romances, where things that had seemed antagonistic or contrary to each other move into balance, subsumed into a bigger pattern. Shakespeare’s favorite metaphor for this is marriage, and the presiding spirits of Loaded are those perversely lovable newlyweds, Jack and Jane, sitting down by the fire listening to the radio (is it that New York station that Ginny hears?). And “anyway,” Reed says, “I hate divorces.”

The Velvet Underground finally foundered after this point, and Lou Reed went home to his parents’ house on Long Island like Arthur Rimbaud in his dejected retreat from Paris back to his mother’s farm. There Reed got some rest, and woke up to find that a new era had begun while he slept, and he began to shoulder the job of making an actual career for himself as if most of this had never happened, and he left behind his little four-album drama of negation and redemption, in its miniature completeness as if it were an antique orrery, a mechanical model of the cosmos that future fans could crank up and set going and learn the process; a schematic of the eccentric orbit the soul shoots off on when it hears that high drone, something like an electric viola, cutting through the many layers of its darkness.