INTRODUCTION

A SCHOOL OF VISION

Thirty years ago it was as if rock music had tapped into a wellspring where Being gushed forth in a play of light and sound that was free and unnamed and not yet frozen into the forms that history and culture demand. It was as if one knew that the wisest cultures find a way to preserve the knowledge of this fountain, an esoteric knowledge hidden from ordinary sight, and it was as if rock music was the way our culture had found, entrusting a cohort of vagabond misfits with this light of the ages.

NICK BROMELL, TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS (2000)

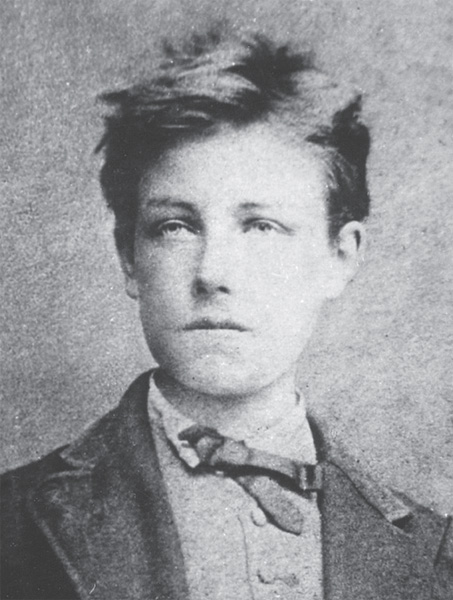

IN 1871 a sixteen-year-old Arthur Rimbaud wrote to a friend saying, “I want to be a poet, and I’m working to make myself a visionary.” The word he used was voyant, which can also be translated as “seer,” or even “medium”—a clair-voyant—“a person sensitive to things beyond the natural range of perception.”

“I hardly know how to explain it to you,” Rimbaud went on. “The point is to arrive at the unknown through derangement of all the senses.” In Rimbaud’s eyes the poets of his day had lost sight of their ancient function. “It is all rhymed prose, a game,” he said of contemporary poetry, “the . . . glory of innumerable generations of idiots.”1 Poets had fallen into a stupid sleep, and no longer saw into the unknown.

Fig. I.1. Arthur Rimbaud at the age of seventeen (photo by Étienne Carjat)

Rimbaud is one of the household deities of rock and roll. Like the family ghost, he pops up at significant junctures. Bob Dylan starts haranguing his friends about Rimbaud in 1963 as he is letting go of the formal constraints of topical folk music, beginning to derange his own senses, and starting work on the surreal rock and roll that will climax with Blonde on Blonde.

Rimbaud’s was not a completely new complaint. Across the preceding century, as technology, materialism, and industrial capitalism were defoliating the imaginative landscape of Europe, certain artists like William Blake had been crying out that the daimonic sources of their ancient calling were being chased out of the world, that art had lost its psychic charge. A new kind of art was needed that would expand vision—a visionary art—an art that would change the way people saw. An initiatory art. A psychedelic art.

Since that time various schools of painters, composers, and writers have taken shape in response to this perceived crisis. A “school” in this sense refers to an informal grouping of artists, maybe not even recognized as a group at the time, who might be working in the same medium, or are perhaps linked by generation, by shared and mutual influence, by cultural affinities and parallel interests.

Many of these were visionary artists in the way Rimbaud meant. That is, the members of these schools wanted to create an art that evokes—and provokes—an expansion of ordinary vision or consciousness, an art with an initiatory function, intended to effect a transformation, a “felt shift in consciousness,” as Owen Barfield says.

The French troubadour poets and the writers of the Arthurian romances formed some of the earliest visionary schools. In the seventeenth century—influenced by Renaissance occultism—the late romances of Shakespeare and the work of “metaphysical poets,” like Andrew Marvell and Thomas Traherne spoke from or evoked visionary experience.

The English Romantic poets, including Percy Shelley, William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and William Wordsworth, were another such school. Romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich, J. M. W. Turner, and Thomas Cole formed another. Later came the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of painters, who imagined for Britain a deep and dreaming past. In France there were the Symbolist schools of poets and painters, who retrieved images from deep in the unconscious.

Occasionally Romantically inclined scholars recognized visionary schools in the distant past or in rural cultures that maintained a living connection to the past, like the German peasants from whom the Grimm brothers collected their stories or Gaelic-speaking crofters in the remote Western Isles of Scotland whose charms and songs were collected in The Carmina Gaedelica.

Much of the way that these movements are taught or written about can give the impression that their concerns were merely aesthetic, a record of movements and countermovements in the rarefied worlds of the avant-garde arts or the academy. In fact, they were responses to a sharpening human predicament that was sensed in one way or another by most people. What would the role of the soul be in human affairs after the obsolescence of an officially sanctioned, culture-wide spiritual tradition, as Western Christendom had been? What would happen to the world if the soul had no role?

By the end of the nineteenth century, it looked as if this artistic agitation was succeeding in moving popular taste toward the visionary. There was a vogue for the supernatural, for stories of horror, ghosts, ancient mysteries, and lost civilizations. There was a new interest in both Western and Eastern esoteric traditions. Mediums and spirit channelers, séances, secret societies, and occult orders flourished. It was at the same time the golden age of English-language children’s literature, itself a visionary school, which expressed a nostalgic longing for the lost magical world of childhood. It was the age, as we’ve mentioned, in which scholars began to collect and preserve ancient folktales and songs. It saw the rebirth of old seasonal festivals like Christmas. This fin de siècle period affected Anglo-American culture in ways that are still potent today, especially in popular culture. It was a direct precursor of the counterculture of the 1960s.

A distinctive feature of these schools of vision is that they were often associated with radical politics. This was not a coincidence. To many members and followers of these schools, visionary art and a kind of illuminated politics were two sides of one coin. There was a connection between calling for a transformed consciousness and a transformed world. The link between new, experiential forms of spirituality and the revolutionary spirit started to become apparent at the time of the great democratic revolutions of the late eighteenth century in America and France. Many 1960s rock-and-roll artists and many in their audience believed that the music was a continuation or a rebirth of this visionary connection, of claiming ecstasy as one of the primary human freedoms, the real fulcrum of “the pursuit of happiness,” the unspoken but always implicit human right demanded by the revolutions that produced the modern world.

It is the argument of this book that 1960s rock-and-roll music is recognizably a school of visionary art. By the sixties visionary interests had been infiltrating popular culture for a long time. They had been a staple of popular fiction since the Gothic novels of the early nineteenth century and became one of the great themes of the movies. It is no surprise that popular music followed suit. So this book will consider some common interests of the visionary schools that continued as important themes of 1960s rock and roll. Among these, first and foremost, is the fascination with alterations of consciousness, ecstatic states, mystical experience, and gnosis, as well as a sense of wonder and the numinous. There is the attraction to alternative political visions, “illuminated politics,” uniting political and spiritual liberation. Closely related was the sense of apocalypse, the imminent transformation or fulfillment of human history. There is the interest in forgotten, rejected, or alternative histories and traditions and in bringing them back to conscious social and political life. There is a strong interest in the exotic, in Eastern spiritual traditions, in myth and archaic wisdom, in the primitive and primal.

Of course, since it was popular music, the biggest theme was love; but this, too, had a visionary connection. It was love as it has always permeated popular song, but also a suggestion of love as the troubadours or Dante understood it: love as a path of transformation.

Finally and centrally, there was a profound connection to African American music and spiritual traditions. But this is not typical of previous visionary schools. It is a new element in this kind of art, and it is what most distinguishes sixties rockers from previous voyants. Visionary sixties rock and roll was the product of a European tradition affiliating itself to the sacred music of the African diaspora. The adoption of rock and roll by a nascent white youth culture beginning in the 1950s gave white musicians and fans a degree of access to the African American practice of “working the Spirit,” a body of religious knowledge and technique for evoking intense experiences of the Holy Spirit through music. The presence of this ecstatic technique, even when diluted and indirect, gave 1960s rock and roll much of its efficacy—it’s what made it work. In its mingling with the spiritual aspirations of European tradition, it was a highly unlikely and wildly effective instance of cultural cross-fertilization.

But there was another place, besides America and Africa, that played a leading role—some might say, the leading role—in the development of sixties rock and roll. That, of course, was Great Britain. British rock and roll was the detonator of “the sixties,” and rock-and-roll fans of the era never forgot it, looking to Britain with a kind of reverence in the belief that it was the matrix of everything that was happening.

The rock and roll of the 1950s could have receded into a number of things—nostalgia or trivia or an aficionado subculture. It might have been just another evanescent teen craze that would in the end leave its fans stranded. That this didn’t happen was mostly the work of the British. Because of their distance, the British fans of this American music were able to see it as a whole, to understand it as a story and envision various ways that the story might go. With an ocean of distance in between, the British musicians were free to decide which aspect or potential of the music would be most useful for their own desires, to select, to re-create, to make this culturally specific black American sensibility into a universal language.

If the British heard one thing most clearly across the leagues of ocean, it was the note of freedom. To them in their country it meant freedom to move and maneuver in an old and weary culture full of ancestral barriers and boundaries and blind alleys. And freedom to reactivate some of their own culture’s forgotten tropes—of the superiority of childhood over adulthood, of life as play—and the suggestion in their nonsense and fantasy literature of a secret that could allow one to pass through those old barriers. In British hands the revolutionary implications of sixties rock and roll grew more explicit with each new album, each new single that shot up the charts.

Rock and roll’s years of underground fermentation in the British Isles served to bring forth something even more potent, more hysterical, more aware of itself as a signpost to new kinds of experience than the original American music. The British music went straight at the fears of parents that in rock and roll there was something that might eventually draw a clear line between one way of life and another. It contributed to a sense that the collection of conventions and symbols, which constituted middle-class life, were suddenly fragile and contingent, faced with a convulsive sea that might wash the whole structure away like a sand castle.

The roaring international ascent of the Beatles starting in 1963 was two things at once. It was a pop phenomenon, larger but not completely dissimilar to others that had been seen before. But at the same time it was a suggestion of a new way to be. It was “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” and it was also the start of the mass popularization of what had previously been a fringe critique of modern Western society. That was implicit even in the beginning.

It will be, I hope, surprising to see how much of a connection there is between sixties pop and earlier visionary traditions. But please don’t think that I’m pretending to decode any secret messages. This is not a rock-and-roll Da Vinci Code, and I am not advancing a startling new theory of what sixties music “really means.” What I am trying to do is restore a mostly forgotten context.

What I mean is that there was an interpretive culture around the music in its own era that has not been retained over the years along with the music, perhaps because it seemed in the immediate aftermath of the sixties to be rapidly dating hippie gibberish. Or maybe because it was kind of embarrassing, or even a little scary, to be reminded how far-out things—you included—had so recently gotten. In any event, while the music was mostly retained, that context faded.

But read any music writing or underground newspaper from the period and you will immediately feel the urgently apocalyptic and visionary mood in which the music was initially received. Over the years the far-out stuff, the complex of ideas and expectations of which the music was thought to be the active agent, has been discretely detached from the recordings. The music has been de-psychedelicized. In this book I am trying to re-psychedelicize it. I am trying to restore some of that atmosphere, because if you can feel even a little of it, you will know the music better.

And also because I think this interpretation was probably true.

You see, this is not a scholarly work, and I’m not an impartial chronicler. I’m biased. My hopes lie in this revolution, as T. E. Lawrence once said about a different revolt. Or as one of my college professors said when describing some piece of early modern magical belief that shows up in Shakespeare, “Not only did Shakespeare believe this, but it’s true!” So I might characterize the stance of this book as, “Not only did John Lennon believe this, but it’s true.” To lay more cards on the table I’ll just say that I believe that a tremendous historical and spiritual process got underway in what’s been known as Western civilization in roughly the twentieth century of the Christian dispensation, and it came to an early (perhaps premature) spike or crest in the couple of decades after the Second World War. One symptom of this process was that interaction between different kinds of consciousness or different states of the soul or between mundane and spiritual experience (there are various vocabularies) became easier and more common. This state of affairs had been developing for a while. In England the Society for Psychical Research was founded in 1882 to study these phenomena. The American philosopher William James undertook a systematic consideration of altered states of consciousness in The Varieties of Religious Experience twenty years later. For a time it was fringe communities that perceived this shift in human experience the most powerfully—scholars, bohemians, monastics, political radicals, occultists, artists—but perhaps the pressure of the enormous disasters of the twentieth century forced the change out into the general culture. Lots of previously subterranean energies came together to create a very big wave. As waves do, after it crested it receded; but I think you are being unrealistic if you don’t think it is gathering again. That’s what waves do. Nostalgia is not a useful tool in this context. The process is ongoing, we need very much to understand it as well as we can, and this music is a royal road into it.

Coming after all those artists and intellectuals who had lamented the disappearance of the mysterious, there came a whole generation that seemed to have been born with the yearnings of French symbolist poets. In the combination of psychedelic experience and fragments of African American ecstatic dance, they were able to gain regular access to realms of consciousness that the European artists had only been able to glimpse in fleeting epiphanies. In the 1960s the long yearning of artists, bohemians, and young people for transport met two things that could actually provide it—the West African/black church liturgical tradition, as transmitted through popular music, and psychedelic drugs. Here was a reinfusion of the ecstatic, the mythic, and the sacred. With a vengeance, and it was the popular song that was transmitting it.

Many people of powerful imagination and insight felt there was a momentary opportunity to replace the official consensus narrative of Western society with what had been a rejected vision, to change the way people understood and experienced life in this society, to make a direct appeal to the imagination of millions of young people by way of music, offering them a larger, freer, more interesting set of imaginative reference points to pattern their lives around. The work of the sixties musicians was intended, like Hindu mandalas or Eastern Orthodox icons, to act as a trigger to transmit a new way of seeing. This initiatory function is perhaps the most telling continuity between sixties rock and roll and earlier visionary schools.

The bands of the sixties were dedicated to creating a particular kind of experience for their audience, albeit in many different ways. Forty-five years ago, Paul Williams, in a review of a Jefferson Airplane concert said, “The Airplane, despite everything, have absolute confidence in their audience. It’s kind of like the early American preacher, in front of his congregation, looking out at the faces of every worst kind of sinner, and knowing that every last mother’s son of them is going to be saved.”2

That confidence, or faith, is what has been missing, but perhaps not for much longer. As the next wave rises and young people again find a source of hope and power, if we know what has come before we may hear something in the first chords of the new that we recognize, and be all the quicker to rally to it. That too is one of the purposes of this book.