The offices of the local bank, a leading microfinance organization in Ghana, were on the top floor of a modern five-story complex in downtown Koforidua. There was, of course, no working elevator, and the stairs were outside. With the temperature in the nineties and humidity near the dew point, Whit and I were soaked and gasping as we reached the entrance to the bank. Outside the door, a wall was covered with illustrated posters—cartoon characters and slogans that are supposed to motivate or inspire you, like you’d see in the break room of a factory. One poster showed a farmer in ragged, patchwork pants standing with his goat. Next to him, a man in a necktie was holding out a bag of bank notes. The farmer was turning away from the money. The poster said: “Do not take a loan if you do not need one.” We pushed open the door and recoiled from the icy blast of air-conditioning as if hit by a fire hose.

Walking over from the Burro office, Whit had explained that the bank made loans to local farmers, merchants, and other small businessmen—anywhere from a few hundred to a thousand cedis—for seed, fertilizer, equipment, inventory, and other capital costs. He had an appointment with the branch manager to discuss several ideas, including financing for agents to build Burro franchises, financing for customers to spread their battery costs over a year, and partnering with the bank to identify potential agents in villages.

“He will see you now,” said a woman behind a beat-up desk, motioning to a side door.

We opened the door and found the manager asleep at his desk. Hearing us enter, he bolted upright and began pretend-typing at his laptop. “Come in, please,” he said, straightening his tie. We sat down and Whit explained Burro, then delivered his pitch for partnering with the bank. “It’s a very good idea,” said the manager. “Please come back on Monday and discuss this with my field representatives.” The meeting was over.

“In other words,” said Whit as we tramped back down the stairs, “stop bothering me with something that might resemble work. Actually he seemed pretty responsive. We couldn’t really have asked for more out of a cold call—especially if the field rep meeting comes off.”

The bank manager was an archetypal white-collar worker in Ghana. Although most Ghanaians—from farmers to market ladies to entrepreneurs like Charlie—work incredibly hard, for some citizens a college degree is seen as a ticket to a job with benefits and no accountability in an air-conditioned office. I make this observation without condemnation. As the Tunisian-French writer Albert Memmi put it in his influential 1957 book The Colonizer and the Colonized, “One can wonder, if their output is mediocre, whether malnutrition, low wages, a closed future, a ridiculous conception of a role in society, does not make the colonized uninterested in his work.” In the aftermath of Memmi’s book, the African has thrown off the yoke of the colonizer. But as the last half century of African history has sadly demonstrated, independence has not wiped the slate clean. It will take time for Africans to find their place in the modern work world.

Meanwhile, Whit needed to find Ghanaian college graduates with an enterprising spirit. He had learned when publishing a help wanted ad that he could eliminate most of the idle opportunists by stating that the office had no air-conditioning. The résumés that flooded his inbox showed alarming job mobility: people tended to change jobs every six months. “I think a few years ago Barclays must have offered some sales position to anyone in Ghana who could speak English and wear a tie—or a short skirt,” said Whit. “It’s like they hired everyone, and paid them literally no salary; it must have been all commission. So of course they all quit, and now every résumé in the country says former sales rep at Barclays.”

Interviews could be surreal. “I went over to Polytech and asked a professor about hiring some electrical engineering grads,” Whit told me. “I said I’m not looking for rocket scientists, just someone with some technical aptitude who can help keep the batteries charged and recognize bad ones. You wouldn’t believe some of the people he sent over. The first guy was this big dude; he comes in and we explain the battery offer. To make sure he understands it, I ask him to pretend he’s pitching the batteries to Rose. So the first thing he asks her is, ‘Where are you from?’ You know, people here can be sensitive about their ethnic background in different contexts, so she was a little taken aback. She says, ‘I live in Koforidua.’ He says, ‘But where are you from?’ She says, ‘Well, I grew up in Accra.’ He keeps pressing: ‘But what language do you speak?’

“She finally says, ‘I’m Fante. Why does it matter?’ He says he wants to know what language to do it in. She says, ‘Just use Twi.’

“So he starts out and devolves into this harangue about the program, how it will never work because people can’t afford the batteries, on and on. So I say, ‘You know, you raise some good points, and these are things we are all discussing on an ongoing basis as a team, but right now, when you’re trying to sell Rose the batteries, this is not the place for that.’

“Then I ask him if he knows how a multimeter works. He says yes, so I hand him the meter and a radio and I say, ‘How would you measure the power this radio consumes?’ He takes the device, and Max, it was like voodoo. He’s just passing his hands over it, and playing with the knobs and crossing the wires; he obviously doesn’t know the first thing about it and doesn’t seem to realize that I do. He thinks he’s fooling me with magic or something. It was fucking laughable. I mean, why didn’t he just say, ‘I don’t know how to use one but I’m a fast learner and I’m sure you can teach me quickly.’”

Even when Whit found job candidates who were honest and enthusiastic about the company and its mission, training required huge reserves of patience, with daily lessons that emphasized the basics. For example, the notion that emails benefit from subject lines describing their content came as a revelation to much of his staff. And all three of his employees needed to learn how to drive. After taking formal classes (paid for by Whit) and getting learner’s permits, Kevin, Rose, and Adam required hours of practice behind the wheel; it fell to Whit and Jan to fill in the skills.

One day, on a harrowing trip to Accra, Rose (in three separate incidents) hit a Barclays Bank, ran a red light, and brushed back a traffic police-lady. “Well, she was in my way!” said Rose in self-defense about the last infraction.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Whit calmly. “You still can’t hit her.”

Rose might have hit another pedestrian had Whit not reached for the emergency brake. “Rose, when I say stop, stop,” he said. “Stop means stop. Right away.”

“Am I doing that bad?” Rose asked.

“You’re doing fine,” said Whit. “You only hit one person and one building in two hours; that’s one incident per hour, so I’ll try to keep your missions under an hour.”

“Oh, you are so bad!” she said.

“Just watch your clutch. It stays all the way in or all the way out, not in between.”

“So when are you going to interview me?”

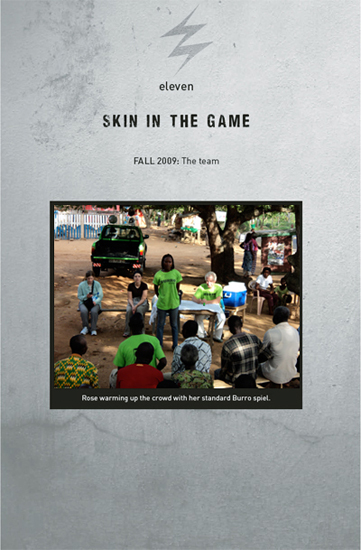

Small of frame and often quiet, Rose could easily be mistaken for a shy person; in fact she was confident and poised. She spoke with an inflective tone that turned every sentence into a challenge, which could seem jauntily flirtatious, in a romantic-comedy kind of way, or playfully mischievous—a fickle streak that was also reflected in her personal appearance. While she usually wore her hair braided into fine cornrows, sometimes she coiffed it into a straight perm, so one never knew what to expect. And contrary to the conservatively dressed women we encountered in the villages, Rose mostly wore blue jeans so improbably tight that I wondered if machinery were required to don them. She was smart, and not unpleasant company on a drive, so long as she was in the passenger seat. It was fall and we were traveling, the two of us, to set up a gong-gong in a Krobo village an hour northeast of Koforidua.

“What do you want me to ask you?” I replied.

“You should ask me about school.”

“Okay, shoot. Tell me about school.” I already knew that Rose was a 2009 graduate of Accra’s Ashesi University College, a private four-year business and computer science school, with a strong liberal arts core, that emphasized entrepreneurship and ethics. Ashesi was founded in 2002 by Patrick Awuah, a Ghanaian graduate of Swarthmore and Berkeley’s Hass School of Business (and like Whit, a former Microsoft manager, although the two did not know each other then). Ashesi means “beginning” in Twi, and Awuah’s goal was to begin by training students as good citizens and critical thinkers, reasoning that success in business would naturally follow. And if his school could also train the next generation of political leaders, so much the better.

“The whole idea of liberal arts, thinking for yourself, analyzing, not cheating on exams—it’s very un-Ghanaian,” said Rose. She went on to describe a depressingly cynical system of higher education, in which credit is contingent on bribing or sleeping your way into favor with key professors. Perhaps she was exaggerating; perhaps academic corruption is more the exception than the rule in Ghana, I don’t know. But based on Whit and Jan’s experience sorting through stunningly inept job applications from Ghanaian college graduates, I was giving Rose the benefit of the doubt. Then, in 2010, a sex-for-grades scandal erupted at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the country’s second-largest college. Apparently Rose was not exaggerating.

“How did you end up at Ashesi?” I asked her.

“I didn’t want to go to a big school like Legon,” she said, using the shorthand location name of the University of Ghana, one of seven public universities in the country. Legon was founded in 1948 as an affiliate of the University of London and now has forty-two thousand students.* “And I didn’t like the national system where your major is determined by your test scores, regardless of your interests.”

Ashesi, which currently has about four hundred students, appealed for its promise of individual attention. “Unfortunately it is very expensive,” Rose said. Tuition ran more than three thousand dollars a year, a fortune by Ghanaian standards. Rose’s family is not poor but hardly affluent—the Ghanaian version of middle class, such as it exists, which is to say lower middle class. Her father, Francis, works for an NGO that supports youth groups; he travels often to London and to southern and eastern Africa. Her mother, Becky, is a caterer, preparing Ghanaian specialties for weddings, funerals, and other social events. The family (Rose has a younger sister, Gracelove, who is studying accounting and fashion design) lives in Osu, the central business and shopping district of Accra, where Rose grew up in a modest two-room home behind a block wall on a narrow one-way street. A childhood in Osu is the equivalent of an American kid’s growing up in midtown Manhattan. In much the same way as New York kids seem to know everything (or at least think they do), Ghanaians from the streets of Osu carry themselves with assurance.

Rose was actually born in Winneba, the large fishing town on the central coast and the easternmost stronghold of the Fante ethnic group. In colonial times the Fante maintained close relationships, in every sense of the word, with the Brits. Fante tend to be lighter-skinned than other Ghanaians, and they often have British surnames (as in Rose Dodd). President Mills is Fante.*

Rose managed to get about three quarters of her first-year tuition covered by financial aid, but she still needed to come up with eight hundred dollars, which she earned by working in a real estate office owned by a family friend. “The second year was the hardest,” said Rose. “I did not have the tuition by the start of the semester, and the rule was if you did not have your tuition you could not get textbooks. So I had to study all year in the library. I still got all A’s, and I told the school, ‘I deserve a scholarship because I got A’s even with no textbooks.’” The school agreed, and in 2007 Rose became the first recipient of an annual twelve-hundred-and-fifty-dollar scholarship in honor of a beloved professor named Princess Awoonor-Williams, a development economist and head of the business department who had received her own doctorate from Howard University.

“Turn here,” said Rose. We bounced up a dirt track that climbed steeply, and when it turned into a path, we left the Tata and walked the last few hundred yards to the high village of Djamam. Along the path, delicate Chinese lantern flowers, drying in the sun, hung from rangy bushes over our heads—Ghana’s version of fall foliage. Wild begonias, pink and blue, crowded along the shoulders of the path like seedling racks at a nursery. Behind us, the land dropped off and the sky opened to a cyclorama of Lake Volta, its water stretching to the horizon and pulsing like a mirage in the heat. For a minute I imagined a distant human ancestor standing in this spot and enjoying the same view, although he would have seen a wide, branching river and not the man-made lake. Thanks to a unique geology that created rich fossil beds, eastern Africa’s Great Rift Valley has become ground zero in the study of human evolution, but man may have also taken his first steps here in western Africa.

“So what are your plans for the future?” I asked Rose as we tramped along.

She laughed. “I have so many ideas. My problem is I get bored. I want to clean up the beaches of Accra, but not as a charity. You see these groups come in and do a big cleanup, but a year later it’s covered in filth again. I want to do it in a way that keeps them clean forever. So people have to see clean beaches as a benefit.”

“You mean tourism?”

“Yes, that could be part of it.”

Indeed, with its miles of sandy coastline, formidable slave castles, animal reserves, friendly citizens, and English language, Ghana has the natural and cultural resources to support a first-class tourist industry. The potential is there, but the problem always boils down to infrastructure. The country needs better roads, safer transport, Western-style hotels and restaurants, cultural attractions that are well maintained, and yes—beaches that aren’t vast public toilets. Rose talked about starting a targeted tour bus service that takes visitors directly from the airport in Accra to the slave castles and the national game park up north; currently there is no easy way to link those sites, and existing public transport, while dirt cheap, is unreliable, unsafe, and downright shocking to Western sensibilities. She also envisions organizing cultural homestays in small villages, and renovating the few tired old beach resorts that do exist.

“Do you think you’ll get bored with Burro?” I ask.

“Not now, because it’s a challenge; every day is different. If it really becomes successful, then I might want to try something else.”

“Spoken like a true entrepreneur.”

She laughed again. “I like working for Whit.”

Left unspoken was the alternative, which for a young woman in Ghana often means working for lecherous creeps. Ask just about any Ghanaian working woman and you will hear stories of bosses who simply assume sex is part of the job description. Indeed, help wanted ads in Ghana often call out young ages and female gender as a requirement; some go so far as to call for “attractive” candidates. Like some cheesy porn movie, engaging in sex can even be part of the “interview” process, but it doesn’t stop there. In late 2010, a story broke about a junior banking rep who came out with some colleagues (all anonymously) to state that the bank set impossible sales targets and that they were expected to sleep with potential major clients to secure their deposits.

The harassment often starts with flirtatious talk and moves on to work dinners, out-of-town travel to conferences (Ghanaian enterprises seem to spend much of their time conferencing, which if nothing else keeps the hotel business humming), late-night work in the room, and so on, with dreary predictability.

A related issue is the secret world of some Western aid workers and businessmen who, under the pretense of being in Africa to help poor people, are more pointedly interested in helping themselves to African women. While not as awful as the criminal pedophiles like the American “businessman” whose arrest I described in the previous chapter, these more garden-variety creeps still rate pretty high up on the icky scale. Whit and I would occasionally run into these malingerers—middle-aged white men living semipermanently in lower-class hotels around Accra, where they run businesses of questionable efficacy and spend their evenings around large dinner tables conducting their own version of social entrepreneurship with much younger locals. I’m thinking this subject doesn’t come up at international conferences on developing-world business opportunities, but based on our observations, the phenomenon is quite real.

The chief of Djamam had traveled, so we greeted an elder who was shaving rattan fronds into strips with a sharp knife, preparing to weave baskets. Rose explained the plan for the gong-gong, speaking in Twi and some Krobo she had been learning, then concluded in English: “So you understand it? There is a one-cedi deposit with each battery. Do you think people will still buy them?”

“I am telling you, they will come,” said the elder. “Do not fear.”

We walked back to the truck, past huts plastered with faded campaign posters emblazoned with a rooster—the symbol of the Convention People’s Party (CPP), founded by Nkrumah himself in 1949 but now a perennial third-place finisher in national elections.* “These people all vote,” said Rose wearily. I think she was tired from all the walking in the hot sun. “If I were them, I would not vote.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because it doesn’t matter. Nothing ever changes for them.”

On Wednesday mornings we had a staff meeting, which lasted about an hour and was run by Jan, following a printed agenda put together by Rose. Jan passed out sheets of colored graphs and bar charts, culled from the Fodder database, that illustrated battery rentals and business growth. “We’re at one thousand sixty-four batteries with a hundred and fifty-seven clients on the new program,” Jan reported one day in August. “Twenty percent are on grid.” Gaining new customers on the electrical grid was significant because it suggested the business could work in cities as well as remote villages.

“That’s great, Jan,” said Whit. “I’m wondering, what’s the best way to get at revenue per battery? It feels like something we should report. Any idea how that’s running right now?”

“It ain’t pretty,” replied Jan. “July revenue was thirty-one pesewa per battery.”

“Ouch,” said Whit. “It’s hard to see how that sustains our business, long-term.” At one point he had come up with a figure of fifty pesewa per battery per month as a bottom line. Calculating that the Koforidua branch could support at least three hundred agents if the routes were designed well, and figuring an average of one hundred batteries per agent, a fifty pesewa average would yield revenue of fifteen thousand cedis per month—a real business, in other words.

“Well, remember, we’re giving away lots of free coupon books to chiefs, queen mothers, and youth leaders in the new villages,” Jan countered. “So we’re doing a lot of promotions right now, and that’s skewing the number.”

“Can we just run a trailing thirty-day so we don’t have to wait until the end of every month for an update?” asked Whit. “That will give us a meaningful number we can constantly track.”

“What does that mean?” asked Kevin.

Whit and Jan together explained the concept of a trailing thirty-day average, and I could see a flash of insight in Kevin’s eyes; he got it right away, but apparently no one in his previous business career had ever bothered to explain it.

“Speaking of promotions, we need to send another all-agent text message,” said Jan.* “We’re running a four-coupon bonus promotion till the end of September and giving agents an extra cedi for every client they convert from the old program.”

“I can do that,” said Whit. “Is the agent contact info in Fodder up-to-date?”

“As far as we know,” said Jan. “Okay, let’s move on to our monthly goals. We have twelve days remaining toward our goal of twenty new agents in August. So far we’ve added eleven. How’s that going?”

Kevin and Rose detailed their plans for adding several new agents by Friday.

“How many of the first agents have converted their clients to the new program?” asked Whit.

“There are still many more to go,” said Kevin. “Only two of twenty-six have been converted so far. Jonas and Yirenchi.”

“What’s our goal for total conversion—end of September?” said Whit.

“Right,” said Rose.

“So we need to stay focused on that while also training new agents.”

“And we need to make sure the new agents are signing new clients,” said Jan. “I think client growth should be our main goal in October, and we’ll need to come up with some new promotion. Now I’d like to spend a few minutes talking about the coupon inventory. Those coupon books are like money, and they need to be under lock and key. I created a database for managing the inventory, but Adam, you’ll need to oversee it.”

Adam, the twenty-eight-year-old accountant, was generally quiet but could be made to laugh easily. Tall, rangy, and handsome, he lived with his brother (a student at the local polytech, where Whit had searched in vain for job candidates) and wore immaculately pressed shirts and slacks. After graduating from Accra’s Institute for Chartered Accountants, he worked as the finance officer for Youth Empowerment Synergy Ghana (YES Ghana), a local NGO. Adam was from Volta Region, stronghold of the Ewe, where he grew up in a village under sacred Mount Adaklu, an imposing butte that marks the spot to which the Ewe first migrated (from lands farther east) some five centuries ago. Although steeped in traditional African customs (his father, as mentioned earlier, was a chief), Adam was also devoutly Christian. Sometimes I would notice Post-it notes on his computer with biblical aphorisms he had jotted down for the day. He never touched alcohol and was apparently an excellent singer in his church choir, although I never heard him intone. We did, however, have several conversations about music after he became aware of the rhythm-and-blues collection on my iPod, and it was clear to me that he had an ear for all sorts of music. Sometimes on village trips we would hear some indigenous music (live or on the radio), and he would explain to me its exact tribal provenance and even the style of dancing one was expected to perform to the beat. I came to think of Adam as the sensitive-artist employee, which is possibly not the best recommendation for an accountant. Indeed, Whit worried that Adam was occasionally in over his head (and was quite frank to him about it), but as we all did, he liked Adam and felt certain he was honest, if not always sharply focused. Part of the problem was that we obrunis had a hard time understanding Adam’s English, which was grammatically correct but heavily accented. This disconnect appeared specific to the Ewe—I also had to listen carefully to understand Charlie’s technically perfect English—and was, perhaps not surprisingly, reciprocal. While Whit and I had little trouble trotting out a handful of basic Twi phrases, our attempts at Ewe were generally met with polite laughter. We simply could not pronounce the words comprehensibly, let alone properly.

“It seems my work day is getting bigger,” said Adam in response to Jan’s request.

“That’s good!” said Whit. Adam laughed self-consciously.

“Well, I was going to suggest that route managers handle their own Fodder input, which would take some pressure off Adam,” said Jan.

“Oh, but we get back so late!” Kevin protested. “That could be a problem.”

“I don’t think it will take that much time under the new system,” said Jan, “but let’s think about it. Maybe you guys can come up with a solution and present it to us. Let’s move on. Where do we stand on the replacement battery sleeves?” She was referring to the green plastic Burro labels that fit over the battery; Whit was concerned that the beat-up labels on older batteries were contributing to the perception by some customers that the batteries were not good. “Does China have the file yet?” meaning the digital artwork.

“Ready to go,” said Whit. “The sleeves should be no problem. They’re being air-freighted so it won’t take long.”

“How do we put them on the batteries?” asked Kevin.

“Heat shrink,” said Whit. “You just use a hair dryer. I asked them when I was there if they would be cut to length and they said yes.”*

“What about more D adapters?” asked Kevin. “We are almost out.”

“They’re on the way,” said Whit.

“I hope they are better than the last ones. I’ve been seeing some in the villages that are already corroded on the contact point. Customers are complaining.” Kevin was keenly attuned to customer complaints, or at least ostensibly; sometimes it seemed like his reports from the field, generally downbeat, were more projections of his own issues than anything the customers actually noticed. When Whit and I talked to customers, they seemed mostly buoyant about the batteries—but then we were obrunis, so praise in our direction had to be devalued by the sycophancy factor, like a currency exchange. “The new ones should be better,” said Whit. “Three-Sixty* tested them in an environmental chamber—blasting them with high humidity and water that’s supposed to simulate two or three years of use. I can’t say they looked pretty after that—I can show you the photos they emailed me—but they still worked fine.”

“Speaking of water damage, I do have a housekeeping issue on the agenda,” said Jan. In fact there it was, “Housekeeping,” on the agenda. “Men, can you please put the seat up when you tinkle and down when you’re done? The rest of us would really appreciate it.”

“Nice segue, Jan,” I said.

“Thank you. Anybody have anything else? Okay, this meeting is over.”

The weekly meetings, which focused on problem solving and follow-up on tasks, encouraged initiative and personal responsibility—qualities not always emphasized in Ghanaian work culture. But Whit wanted—in fact needed, if he were to spend much time at all back home with his family—Rose, Kevin, and Adam to take even more “ownership” of the business. They needed some skin in the game. So he designed a bonus plan, which he unveiled at the August 26 meeting.

“I’m open to feedback on this,” he began, “but here’s what I’m thinking so far. I don’t want to set impossible goals; this year we’ll be hard-pressed to just break even, and I want you guys to be motivated. So this is based on some realistic goals that will help make the company a success. These bonuses aren’t pocket change. We’re not talking bags of rice here. We’re talking real money. Each of you has a chance to get a thousand-cedi bonus, paid in January, based on Burro results through December. That would be the maximum per person.”

A thousand cedis was considerably more than a month’s pay for each of them.

“Now, don’t get your hopes up; frankly there is little chance you will get all that money. It’s incremental, and we’re asking all of you to do a lot of crossover work and build as a team to grow the company. So here’s how we see it.”

Jan went to the whiteboard and started diagramming as Whit continued.

“Two hundred cedis of your bonus will be based on your own personal goals and objectives.”

“You mean like our job description?” asked Rose.

“No. That’s different than goals. Adam and I are already working on very specific objectives for him, with completion dates, and Jan and I will get similar detailed goals for you guys. If, in the fair and reasonable decision of management, you have met your objectives, you will get this two hundred cedis.

“Another two hundred cedis will be tied to the other two people meeting their goals. Because we are a team. So Kevin, you have an interest in Rose and Adam meeting their goals, and Rose, you want Kevin and Adam to meet their goals. You guys have to work together.

“Then two hundred cedis is tied to meeting cost targets, keeping our costs down. These will be based on things you can control, not salaries or rent, but things you guys can control in the day-to-day way you run the business, like buying supplies and maintaining the cars. I’ll work with Adam and Jan to define what reasonable costs are. This will be a sliding scale, it’s not all or nothing. So if you hit the cost-control target completely, you get the full two hundred cedis, but you may get one third, or whatever, depending on our business costs. I need you guys to pay attention to spending, okay?”

Nobody said anything. I was thinking this could possibly lead to shortcuts, possibly even dangerous ones when it came to car maintenance, but I kept my mouth shut. Jan probably had a formula for that.

“Finally, the last four hundred cedis will be tied to revenue. We’ll work with Adam to define some specific revenue targets and how to report on them daily—probably some evolution of the thirty-day trailing number. Maybe the bonus will be tied to revenue per battery as well as overall revenue, I don’t know.”

Silence.

“Well?” said Whit. “Like I said, we’re open to feedback.”

Nothing.

Whit was turning red. He grabbed a marker and jumped to the whiteboard, crossing a giant X through the whole schematic Jan had just written. “Or we can say forget it. I’ll just keep the three thousand cedis! Because I’m not hearing anything from you.”

Jan stepped in. “We need you guys to tell us what you think. This bonus plan represents about fifteen percent of your annual income. That’s considered quite an attractive bonus in the U.S., but we don’t know about in Ghana. Is that normal? Better than usual? Less than usual? We need you to tell us. Does this interest you at all?”

“I’m not looking for pats on the back,” Whit added. “I’m looking for constructive feedback.”

“If we get this bonus, you will have so many pats your back will be aching,” said Kevin.

Everybody laughed. “That sounds like an Akan proverb,” said Whit.

“It’s good,” said Kevin. “We’re not saying the bonus is not good. But it will remain to be seen if we can make these goals and numbers.”

“Well yes, that’s the whole point,” said Whit.

“Have you taken into account that our clients have very little money?” said Kevin.

“No!” said Whit emphatically. “What I mean by that is, these will be numbers that we have to hit or we’re out of business. So it doesn’t have anything to do with our clients’ spending power. We need to have a hundred agents with a hundred batteries each to start making a profit—and that’s with you guys, a staff of three. The bottom line is, we’ve gotta hit these numbers by the end of the year or we’re done. We pack it up. We’ve got to show to investors—and I include myself as the guy who has already invested a quarter of a million dollars into this business—that we can start up a regional branch that makes money in a year.”

“And the fact is,” said Jan, “Whit has done a lot of research into what our clients are spending on batteries, and they spend a lot—several cedis a month.”

“The whole country spends fifty million dollars, eighty million cedis, on batteries every year,” said Whit. “We have an offer that beats the competition hands down. Frankly I think that anyplace we are in business we should be grabbing one hundred percent of the market share. All of it.”

Jaws hit the table. Whit paused and looked around.

“Okay, let’s be generous and say we only get twenty-five percent, nationwide. That’s still a fifteen-million-dollar business in Ghana. A business that makes money and helps low-income families live better lives! We are doing something very different here, and you guys are leading it!”

At that point I thought Whit might strip down to tights and a cape, and leap off the veranda to save Koforidua.

Finally Rose spoke. “For me, I don’t take satisfaction from a bonus; I take it from not being bored on my job. But it’s good that we have it.”

“That’s fair enough, and a good point,” said Whit. “I think we should all feel proud and satisfied in our jobs. This is a country with thirty percent annual interest rates. Most businesses here have only one model: buy cheap, sell dear, move inventory quickly. It’s the only way they can profit with those interest rates. But we are building a completely different model. The goal this year is to prove we can do it in one place. The goal next year is replicability.”

The bonus plan required cooperation, and getting everyone on the Burro team to cooperate could be complicated by ethnic differences. All three employees were from different regions and tribes, with different customs and languages. Ghanaians pride themselves on tolerance and rarely express ethnic prejudices openly. But the truth is, they think about them all the time, and when pressed they will gladly share:

“The Ewe, they are very suspicious,” said Kevin one day as we were driving the battery route. “They won’t buy anything until they are sure it is good. The Krobos, if they see their uncle or brother buying it, they will buy it. The Ashanti? Oh, they will buy it if it is good, but only because they make up their own mind.”

Kevin, of course, was Ashanti.

“Now the Ga,” he concluded, “they all have the big mouth.”

After Whit hired Kevin as his first Ghanaian employee, Charlie lobbied strongly for the hiring of Adam, an Ewe, for the accounting position. Fortunately for Whit, an equally qualified Ashanti candidate was not available for six weeks, allowing him to avoid the issue. But he and Jan had several discussions about whether it was right to consider ethnicity in hiring. Did it make sense to spread the jobs out equitably among ethnic groups? Or was it wrong and racist to even care? The issue was never settled, but Whit felt satisfied that his Ghanaian staff, accidentally or not, reflected a broad pool of ethnic groups.

Politics, as in national politics, could make for office tension as well. One day, again in the car with Whit and Kevin, I wondered out loud if there were any real ideological differences between the country’s two main parties. Whit answered no, but Kevin disagreed. “The NPP is more business-friendly,” he said. “They favor less taxes.”

“Well, that was certainly their campaign manifesto,” countered Whit, “but as a practical matter I don’t discern any substantive difference between the parties. It’s all about patronage, and not just in Ghana. I mean, hiring your cronies is how you stay in power. Breaking that cycle is a huge challenge. Somebody has to have the courage to step up to the plate and say it ends with us, but nobody has done that. I mean, Kufuor’s government gave thirty percent raises to state employees three weeks before leaving office.”

Indeed, there is virtually no accountability for government spending in Ghana. A 2004 report by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund found huge discrepancies between budgeted and actual expenditures. For example, from 2000 to 2003, the Ministry of Education spent 39 percent less money than budgeted on actual services, while spending 45 percent more on salaries. The situation in the Ministry of Health was even worse, with services receiving 67 percent less than budgeted, and salaries going overbudget by 76 percent. As Tony Killick of the Overseas Development Institute wrote in a recent paper on Ghana: “There is evidence of large leakage in allocated funds between their release from the centre and their arrival at the point of service delivery.”

Kevin laughed nervously at Whit’s mention of Kufuor’s vote-buying “raises.”

“You think that’s funny?” challenged Whit. “I don’t. Because it’s your money, and really, money that isn’t there. Money that could be paving these messed-up roads.” He swerved to dodge a pothole, paused, and took a long breath. “I think it’s scandalous.” Conversation dropped off.

I walked to the immigration office in Koforidua’s ministries complex to pick up my passport, which I had to submit (along with twenty cedis) for a visa extension. It’s a queasy feeling to surrender your passport in a foreign country—“Come back in a week,” the stern-faced immigration lady told me—and especially troubling when you come back in a week and she says, “Come back in one more week.” But finally the day arrived. “Have a seat,” the same unsmiling lady said, motioning to a plastic patio chair. I thanked her and bowed, although her invitation troubled me. I had assumed I would simply grab my passport and hit the road, but apparently not. I crossed the tattered linoleum floor and sat down. The small, dusty room was crowded with six beat-up desks, at which sat six women, nearly identical in their starched green uniforms with gold epaulettes and shoulder braids. There was not a scrap of paperwork on any desk, and no work apparently in urgent need of attention.* Instead, all six women sat with their eyes glued to a TV in the corner, which was playing a Nigerian movie. The woman whose desk was closest to the TV presided over a sizable library of DVDs, suggesting that film appreciation was, in fact, the real work at hand.

It was midday and meltingly hot—sweat poured from my brow even though I sat utterly motionless—yet the overhead fan was not turning, was perhaps broken. One of the women took my “Document Retention Receipt” and left the office; now I had no passport and no proof of ever handing it over to this zombie bureau, but I tried to remain calm, if not cool.

I focused on the movie, a typical Nigerian potboiler. Most revolve around deceitful businessmen, crooked politicians, beautiful women in danger, and one misunderstood but honest man out to save the country, who invariably dies, usually slowly and after prolonged torture at the hands of corrupt cops, orchestrated by an evil shaman. This particular film was not breaking any new ground. Minutes passed, scenes changed. A couple was asphyxiated by carbon monoxide in a Mercedes-Benz. The immigration ladies were arguing about whether the dead woman was pregnant and by whom.

Finally my passport arrived. But instead of handing it over, the lady sat down at her desk and withdrew a large dog-eared ledger book that appeared to predate the Ashanti-Fante War of 1806. She opened my passport, turned to the ledger book, and started writing. And writing. And writing.

The movie plot thickened. There was a motorcycle crash, a man ended up in the hospital. His wife came to see him. “You shouldn’t do this to yourself,” she said to him. Still the passport lady wrote.

The movie ended. The credits rolled. I noticed that the character of “Deacon” was played by “Unknown,” which I found curious. I guess by the time they finished making the movie, they had forgotten all about that guy who played the deacon. Maybe he will turn up one day and identify himself. Maybe, like me, he was a man without any identity documents. Still the lady kept jotting in her passport ledger book. The woman with the DVD collection popped in a new movie. During this entire time, no one else in the office took any action that I would classify as work; in fact, never on my several visits to Immigration did I see any worklike action undertaken at all, other than that pertaining to my own visa. Finally the lady closed her ledger book and handed over my coveted passport. “Check it, please,” she said, “to make sure the extension is correct.”

“Can I see your driver’s license and fire extinguisher, please?”

Fire extinguisher? Rose and I were driving out to Fantem, a postcard African village of thatched-roof huts on Lake Volta, where a fisherman had promised us some fresh tilapia and duck eggs. The police roadblock was in the usual market-day location just outside Koforidua, and I was used to slowing down and waving as the police eyed our registration and insurance stickers on the windshield. But today’s demand for a fire extinguisher was new—or rather a new variation on the too-familiar police shakedown. It begins with a citation for some obscure infraction. You will have to go to the police station, or to a judge in a distant town. All of this will take time. For a small consideration the matter can be settled right now.

As the young officer wrote me up, I told him, “I was not aware I needed a fire extinguisher,” imagining that in the unlikely event my car were to immolate, I would leap out and run before it exploded. But the law was hardly about safety or logic. Perhaps some importer of fire extinguishers was on friendly terms with the government; a crackdown on missing extinguishers (who knew?) would drive business. The policeman who pulled me over was threatening to withhold my international driver’s license until a court date. I was already without a passport, at that time still in the bureaucratic labyrinth of a visa extension. My license was my last proof of identification.

I called Whit while Rose talked to the cop in Twi. “Sit tight,” said Whit. “We’re on our way.”

Rose and the cop kept on talking amiably; he was clearly curious about our business. Soon Rose was holding up a battery and launching into the spiel, which I could almost recite in Twi at that point. Soon they were laughing about something. Then the cop turned to me.

“Your woman has spoken for you,” he announced in English. It was meant as an insult: a man who needs a woman to get out of trouble is not a real man. And by calling Rose “my woman,” he was, I think, implying that I was one of those lecherous Westerners who come to Africa for all the wrong reasons. But it was all sticks and stones. He could have called me a child molester as long as he gave me back my international driver’s license.

“I will tear up this ticket,” said the officer, “but you must pay for the paper.”

Ah, the paper! I was ready to hand him a ten-cedi note and be done with it, but Rose stepped in and negotiated the payment down to five cedis (about $3.50). He handed back my license, and we were off to get fish and eggs. I called Whit: “We’re in the clear. See you this afternoon. Get a fucking fire extinguisher.”