In mid-September of 2009 we got the Tata “branded,” in the current business lingo—that is, painted Burro green with the Burro logo and slogans affixed to it in black self-adhesive vinyl (known in the trade as SAV). Branding, or “impact advertising,” is pretty much what marketing is all about in Ghana; the country’s low literacy rate and dozens of languages make it a challenge to convey information about your product. TV commercials have limited reach, since relatively few people own sets (although radio is popular). When you consider that Ghanaians spend virtually all of their waking hours outdoors (their tiny huts and houses, meant for sleeping, are cramped and stuffy by day), it’s not surprising that outdoor advertising is the primary marketing space.

Commercial signage is everywhere; on the low end are hand-painted shop signs created by relatively skilled artisans, with studios on seemingly every block. These colorful kitsch masterpieces are designed for illiterate customers and illustrated with representations of the wares for sale—shoes, fish—or bizarre interpretations of the services rendered, such as severed hands and feet to announce a manicurist’s shop. Many, perhaps most, small businesses in Ghana are named after seemingly irrelevant inspirational passages, such as the God Will Do Welding and Body Shop, Not I But Christ Fashion, Thank You Jesus Spare Parts, It Is Jesus Catering (“This is delicious, what is it?” “It is Jesus.”) and my favorite: the unfortunately named Never Say Die Until the Bones Are Rotting Fish Store. In his recent book The Masque of Africa, V. S. Naipaul succinctly described the proliferation of African Christian signage “as though religion here was like a business that met a desperate consumer need at all levels.”

In recent years, however, the Man from Galilee has faced stiff competition in naming rights from President Obama, a hero in Ghana and indeed most of sub-Saharan Africa. Now you can stay at the Obama Hotel in Accra while snacking on Obama Biscuits, a locally made sugar cookie that even appropriated the famous poster art by Shepard Fairey.

But the charming hand-painted business signs are merely the bottom warp in a tapestry of outdoor advertising dominated by big multinational impact campaigns. When Vodafone, the British mobile phone giant (45 percent owned by Verizon), bought Ghana’s state telephone company in early 2009, they literally painted the country red. Along roads from east to west and from the Atlantic to the Sahel, entire villages of adobe huts were brushed, seemingly overnight, in bright Vodafone red, punctuated by the company’s white apostrophe logo. Streetlights were draped in Vodafone banners, bridges transformed in red; even major landmarks, like Accra’s Nkrumah Circle, were co-opted by Vodafone flags and signs.

It’s not terribly hard to get your brand plastered across Ghana. Until recently, rural Ghanaians who lived along main roads were happy to let companies turn their huts into giant advertisements at no charge; the association with an “important” brand connoted status and was considered desirable—plus you got your house painted for free. “At first people were ridiculed for letting the companies paint their houses,” said Kevin, who used to work in promotions for Guinness, “but then it became fashionable.”

But as often happens with outdoor advertising, the branding of Ghana has devolved into an arms race. Today you can drive through villages that have been transformed into kaleidoscopic brand wars—every other home is either Vodafone red or the yellow of MTN, a mobile phone competitor and the largest carrier in Ghana; across the street are whole-house ads for Pómo tomato sauce (red and green) and Snappy peanut snacks (red, blue, and yellow). On the next block, Coke and Guinness duke it out in the beverage wars. (Besides its beer, Guinness owns the Malta soft drink brand.) Kevin told me that Ghanaians have started to show signs of branding fatigue and are no longer willing to offer up their homes as free billboards. Payments are increasingly common, especially in prime locations. And of course, companies pay towns and cities for the right to brand public spaces. These companies understand the importance of brand identity in Africa. Whit argued that brands matter even more to low-income consumers, precisely because they cannot afford to take chances on unknown products.

Yet despite the relentless branding of commodities like phone services and taste-alike beverages, the African retail segment is otherwise surprisingly under-branded; most consumer products, from housewares to appliances to clothing, are essentially generic and undifferentiated. Nobody, it seemed, was as focused as Whit on building a brand that would earn the trust and loyalty of low-income African consumers in products that are essential to them.

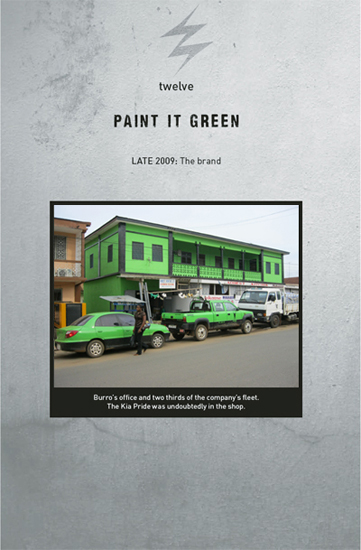

With revenue of some two hundred cedis a month, Whit was a long way from branding the countryside—not that he didn’t have dreams of seeing entire Ghanaian villages painted in Burro green. For now he’d have to settle for company T-shirts, shop posters, and branding the two vehicles, starting with the Tata.

Through Rose we had established a relationship with a company in Accra that specialized in orchestrating brand campaigns; basically they took care of the details involved in ordering clothing, signage, car branding, and any other impact promotions you needed. If you wanted to face-paint Ghanaian market women in the color of your brand, they could probably arrange it.

Or at least, say they could. It didn’t take long for us to figure out that what the company promoted best was itself. The outfit was run by a physically imposing man I’ll call Dave, a member of the Ga ethnic group of greater Accra. Perhaps because they are primarily an urban people, the Ga have a reputation among Ghanaians as being aggressive and in-your-face. They are the New Yorkers of Ghana. They talk fast. With his thick-rimmed glasses and shaved head, Dave certainly fit the physical bill of a Big Man not to be messed with; I have no doubt his intimidating image was carefully cultivated—branded, you could say. In fact, as testimonial to the importance of protecting your brand, Rose had stumbled upon Dave’s company by accident, its name confusingly similar to a far larger, better established, widely known competitor she thought she’d found when first meeting him.

At our first meeting in Burro’s Koforidua office, Dave could hardly sit still in his chair, so eager was he to share his brilliant ideas for taking Burro to the top. Whit wanted T-shirts; Dave talked about vests with lots of pockets for the batteries. Jan wanted to know what a public-address system for the truck would cost; Dave was already talking about composing a Burro jingle and hiring actors for radio ads. He was going ninety miles an hour, but he didn’t really understand the business yet. It was, in short, all talk, and not a lot of details at that.

Nevertheless, Jan managed to pin him down on a T-shirt order, and within a few days he had provided some paint samples (on twelve-inch-square metal plates) for branding the cars.

Burro’s green color was somewhat hard to reproduce, a concern known to Whit when originally adopting it. The Burro brand identity was developed under the direction of Michael Connell, Cranium’s former creative director, by the Los Angeles design firm Creable. To make a green that would really pop in print, the designers chose a Pantone spot color and specified two “hits” of the ink on a super bright white stock. If done properly, it looked great, popping vividly—almost neon. But it proved difficult to duplicate in Africa, where printers did not necessarily have the ability to match Pantone colors or to provide the correct coated paper stock. Even harder were clothing dyes and automobile paint tones because (at least in Africa) they were not as standardized as printer ink.

So it took a few weeks, but finally Dave managed to source T-shirt dye and car paint that Whit felt were close enough to move forward. We drove down to Accra on a Saturday to pick up the truck and the T-shirts, pulling in front of Dave’s office, in a neighborhood with the exquisitely colonial name of Asylum Down, right on time at two o’clock. The truck was nowhere in sight along the narrow street.

“Where is our truck?” Rose asked the receptionist, an attractive and slightly cross-eyed woman in her thirties. She sat behind a large desk in a cramped and cluttered foyer of the building. On one wall was a glass case displaying shirts branded with the colors and logos of perhaps a dozen multinational companies.

“It is still being washed,” she said. “Please wait.”

“But we called two hours ago and it was being washed,” said Rose. “That is quite a washing.”

“Please, wait,” she said again. “I will prepare the bill.”

She left and returned a few minutes later with an invoice. Rose looked at the bill and said, “This isn’t right. The shirts were supposed to cost five and a half cedis each, and you have billed us six cedis.”

The receptionist extended her hand and took the bill, then perused it. “Dave will be here soon,” she said.

“Can I look?” said Whit. He took the bill and turned to the second page. “Whoa! Six hundred twenty-eight cedis for the sound system?” He was referring to the charge for buying and installing the amp, microphone, and rooftop speakers. “On our pro forma, which I have here, Dave said that would cost a hundred and eighty cedis. I know he did call and say that he couldn’t get that system and the one he found would cost more. But I figured, like, ten or fifteen percent more. This is three hundred and fifty percent more! I’m sorry, but that’s unacceptable. I would expect a phone call for that much more.”

“That is what it cost,” said the woman blandly.

“I don’t doubt it,” said Whit. “But it’s not even close to what I agreed to pay. So maybe I’ll say just take the whole system out. I mean, I will talk to Dave when he gets here, but that’s just outrageous.”

Dave walked in, handshakes were made. Still no truck. “It’s on the way,” he said. “It looks fantastic.”

“We can’t wait to see it,” said Whit. “But Dave, I am concerned about the invoice.” He pointed to the audio system charges, comparing them to the estimate. “I’ll be honest with you, Dave. I don’t understand why you didn’t call me about this. I don’t like surprises in my business, and this is a very big surprise.”

Before Dave could respond, a worker came through the door, jangling the Tata keys. “It’s here,” said Dave. “Let’s go.”

We walked out to the street and beheld the Tata, which was now a very bright green. It was, indeed, very cool. We walked around it, inspecting the paint job. We hadn’t been sure quite what to expect in terms of quality—we had joked earlier that we hoped they wouldn’t paint the tires green—so the professional workmanship came as a pleasant surprise. Although Whit noticed a couple of small drips around the windshield-wiper base, it was overall a very clean job. Even the doorjambs were properly painted. The vinyl logo applications were all done to spec. On top of the roof, mounted to the rollbar, were two large gray cone speakers. Inside the cab, a public-address amp with a tape deck was mounted on the console; connected to it was a microphone. Whit couldn’t resist. He climbed in, turned on the ignition, switched on the amp, and grabbed the mike. “Better battery, half the price!” It was loud. We jumped, at first from the surprise, then with delight. This could be all sorts of fun.

“Man, we can really scare kids in the villages now,” said Whit. “Nice job, Dave,” he added.

Back inside, Dave offered to take fifteen percent off the price of the audio equipment. Whit grudgingly accepted but pointed out he still didn’t understand what he was paying for. The invoice itemized two amps—an Ahuja “complete public address” for four hundred thirty-two cedis and another, with no brand listed, for one hundred forty-eight cedis; we could only see one amp, and it was not made by Ahuja. Where was the other amp, and what did it do? Dave didn’t know, he admitted. The technicians installed everything. “Can I see the owner’s manuals for this stuff?” asked Whit.

“I will get them for you,” said Dave. “They are not here.” Whit rolled his eyes. I went out to the truck to see if I could locate all the equipment. I looked under the seats, under the hood, under the dash. I saw only one amp, but I also noticed that the truck’s original radio was missing; there was a hole in the dashboard where it belonged.

“Whit, the radio’s gone,” I said, back inside.

“Huh?”

“As in, not there.”

“Oh, we have it,” said Dave. “We took it out so it would not be stolen.” A few minutes later an employee emerged from the back room with the radio, wires dangling. I went out to monitor the installation. The guy couldn’t get the antenna cable hooked up—for some reason it was now too short. I went back in and found Rose and Dave in a heated discussion about the T-shirt invoice. “I am not paying this,” she said. “The agreement was for five and a half cedis each, not six. I will pay the original price and no more.”

Dave seemed like the type who was not used to women standing up to him; I thought I detected steam coming out of his ears. He hovered over Rose and jabbed his finger at her. “You are Ghanaian!” he bellowed. “Surely you understand the problem of inflation in this country!”

Up to now Whit had been listening, letting Rose take charge—which she was doing very well. But I could tell he was getting angry that Dave would try to bully her (not that it was working). “Inflation?” said Whit incredulously. “Ten percent a week? Sorry Dave, but you are insulting our intelligence. The price was five and a half last week when we paid you a deposit. If it was going to be higher, you should have told us then.”

Outnumbered, Dave backed off. The technician came in and announced he could not connect the radio antenna without adding an extra length of cable. Whit rolled his eyes again. “It’s definitely not good to cut and splice coax,” he said, “but it sounds like we have no choice.” Whit shot me a look that said “What next?”

We had arrived in the Kia, with plans to leave it behind for its own paint job. But at this point, Whit wasn’t sure he still wanted to do any business with Dave. The guy had also been playing us along on getting posters printed; every week it was “next week” when his printers would get the right ink, and as with the car branding, price seemed to be arbitrary. Meanwhile, Burro was developing a network of agents who owned shops in key market towns and along main roads. Unlike “freelance” agents, who could walk around and introduce the battery to their neighbors, shopkeepers couldn’t leave their stores and sell door to door. They needed signage to announce the product. Without what Whit called “promotional air cover” to drive sales, he was worried that busy shopkeepers would lose their enthusiasm for Burro—a deadly setback for a start-up.

So the need for posters was immediate, and Dave was punting. Fortunately we had found a reputable printer on our own—thanks to a brochure in a hotel, of all places. He was a charming and very professional Lebanese immigrant named Stephane Fawal, with many years’ experience as a printer both in Ghana and France. While Dave hemmed and hawed about getting ink (and revised his price daily), Stephane was ready to roll; in fact we had met with him earlier that day to talk about options.

The next day, Sunday afternoon, Whit and I decided to take the truck out for a test run on one of the battery routes. We headed west out of town on a dirt road to Ampedwae. You could say our first test was more anthropological than technical. There is a part of the male brain, fully developed by the fifth grade and requiring no further academic discipline or apprenticeship, that recognizes categorically the intrinsic hilarity of amplified bodily noises. Mel Brooks paid homage to this branch of connoisseurship when he declared that as long as he was making movies, farts would be heard. In that spirit, Whit and I quickly performed a rigorous field test of belching into the microphone before moving on to more technical trials. I plugged in my iPod and cranked up some best hits from E. T. Mensah, the father of postwar Ghanaian highlife music who synthesized American big-band jazz with African rhythms. That turned some heads along the road: it’s not exactly the sort of music you heard every day in Ghana in 2009, especially blasting from a bright green truck with two obrunis in it. We waved at farmers and market ladies and children along the road, and they all stared and laughed at the spectacle. “White folk actin’ stranger every day!” Whit said like a 1930s Hollywood plantation mammy. We switched the soundtrack to Bob Marley, which is to say the soundtrack of life in Ghana, and watched children break into frenzied dance moves as we passed. They dropped their loads of water jugs and plantains and chased us like we were an ice cream truck.

“Better battery, half the price!” Whit recited into the microphone. “Get more power for less! Burro batteries! Get them from Benjamin the chemist in Supresso!” We drove on, finally reaching a village, called Asampanyie, that Burro had not yet opened up. As we scaled a rise into the village center, our speakers met their match: a circle of drummers under a mango tree were beating out a steady rhythm as dozens of people in dark robes and dresses shook their hips. It was a funeral, which in Ghana generally turns into a big party with lots of alcohol—the African version of an Irish wake. We pulled over and were instantly swarmed by tipsy mourners. Whit gave a spiel on the batteries and signed up a few new customers, who would be served by an agent in nearby Mangoase. I pictured them waking up sober on Monday morning and wondering where the hell they got these new green batteries.

Our fun with the sound system was short-lived. After just a few days of Ghana’s punishing roads, the cheesy die-cast U-brackets meant to hold the heavy speakers onto the truck’s roof bar had twisted and snapped. Whit called Dave, who said it sounded like we would need heavier brackets, as if the road conditions in Ghana were some surprise to him. Back we drove to Accra, back to Dave’s office, where two of his workers brought out a pair of new brackets. I could see they were indeed much heavier, but they were also obviously homemade, with amateur welds that looked weak. The black paint was still wet.

“I think these will break,” I said to Whit. He agreed.

“No good,” he told the workers.

They went back inside and brought out a pair of new factory brackets in packages, better and stronger than the original ones. But although these brackets were made by the same company that made the speakers, Whit and I could see that they didn’t quite fit. To attach them involved removing from the back of the speaker a gasketed metal ring that protected the magnet and all the circuitry from rain; the new bracket didn’t work with the old gasket ring, and there was no seal. “These will leak,” said Whit, pointing at the fit.

At this point the two guys ignored us and started assembling the brackets to the speakers. “What will keep the water out?” asked Whit, pressing on. One of the men started yelling at Whit in Ga, a language we understood even less than Twi. “I’m sorry, I don’t speak Ga,” said Whit.

The man scowled. “Do you speak any Ghanaian languages?”

“Yes,” said Whit. “English.”

“They will not leak,” he said firmly.

“Okay,” said Whit, holding up the water sachet he was drinking. “Let’s pour water on them and see.” The man ignored Whit, who took out his cell phone and called Dave. “Tell your men to take it all out. The whole system.”

The worker’s cell phone rang. He spoke briefly to Dave in Ga, then hung up. “I have been a technician for ten years,” he said to us, seething. “I know what I am doing.” It took over an hour to remove the sound system, because the technician didn’t have a Phillips head screwdriver and had to use a penknife.

Our next meeting was just around the corner, at the Asylum Down office of MMRS Ogilvy, the Ghana branch of the global advertising firm. We had an appointment to meet with the business development director, a woman named Josephine Komeh, to discuss possible ways the company could help shape the Burro brand. Whit knew his business was (at least for now) insignificant to an agency that handled the Ghana accounts for giants like Nestlé and Unilever, but he also felt it would be good to make the introduction. So when Rose set up the meeting with a friend who worked there, Whit was happy to follow through.

We filed into a large conference room and shivered from the air-conditioning. There was a flat-screen projection system and a glass trophy case filled with Gold Gong-Gong trophies—shaped like cowbells—which I gathered were Ghanaian advertising awards like the American Clios. Whit unpacked his laptop and was connecting to the projector when a young man came in. “I’m very sorry,” he began, “but there seems to be a misunderstanding. Josephine is in another meeting and cannot make it, but I will be happy to listen to your presentation.” He seemed pretty low-level, and his English was only fair.

“Umm, okay,” said Whit, tentatively. “How much time do you have?”

“Five minutes.”

“Oh, then forget it,” he said, closing his laptop. “We can’t explain our company in five minutes. Thank you for your time.”

“One moment please,” the man said, leaving. A few minutes later he returned. “Can we do it next Monday?” he asked.

“No, I’m sorry,” said Whit. “We are based in Koforidua and we are very busy up there. It’s hard to find time to come down to Accra.”

“One moment.” He left again. This time he came back with the big shots: Josephine Komeh herself, plus the agency’s creative director, Kweku Popku. After pleasantries, apologies, and business cards had been exchanged, everyone sat down and Whit launched into his presentation.

“I’ll be honest with you,” he began, “I don’t think we’ll be able to afford you. But I’d like to introduce you to the company so you are aware of us, and as we grow, hopefully we might be able to work together. At Burro we believe passionately in the power of the brand we are building, and we know how serious your agency is about brand development.” He described his career and his previous time in Africa, then turned to the slide show. After a few introductory images came a slide titled “Burro Vision.” Next to a photo of Whit, Kevin, and Hayford riding triple on Hayford’s bicycle were four bullet points:

![]() Profitably deliver affordable goods and services that empower very low-income consumers to do more with their lives

Profitably deliver affordable goods and services that empower very low-income consumers to do more with their lives

![]() Leverage direct sales channel across multiple categories

Leverage direct sales channel across multiple categories

![]() Collaboratively craft a world-class company

Collaboratively craft a world-class company

![]() Build a new kind of brand for the developing world

Build a new kind of brand for the developing world

Whit explained the points, then clicked to the next slide, titled “The Burro Brand”:

“Burro”

![]() Memorable and short

Memorable and short

![]() Easy to spell and pronounce

Easy to spell and pronounce

The Donkey

![]() Cost-effective productivity enhancement

Cost-effective productivity enhancement

![]() Trustworthy, hardworking companion

Trustworthy, hardworking companion

![]() Tangible thing, simple, real presence

Tangible thing, simple, real presence

“Do More”

![]() Aspirational promise—Burro does more

Aspirational promise—Burro does more

![]() Proactive call to action—you should too

Proactive call to action—you should too

The next slide laid out the financial opportunity:

![]() Consumers are currently spending $2 to $6 per month on throw-away batteries

Consumers are currently spending $2 to $6 per month on throw-away batteries

![]() Additional energy demand can be met with batteries

Additional energy demand can be met with batteries

![]() $2 to $4 per month on kerosene for lighting

$2 to $4 per month on kerosene for lighting

![]() $2 to $4 per month on cell phone charging

$2 to $4 per month on cell phone charging

![]() Substitute Burro battery service for these existing expenditures

Substitute Burro battery service for these existing expenditures

![]() Put the economics of rechargeables within reach of low-income households

Put the economics of rechargeables within reach of low-income households

![]() Burro is better—and half the price

Burro is better—and half the price

![]() $50 million market opportunity for batteries in Ghana alone

$50 million market opportunity for batteries in Ghana alone

There were twelve slides in all. At the end, Whit said, “Our most immediate need from you is a multilingual audio pitch to create an initial exposure to the Burro brand and to drive sales of Burro’s initial offerings. We need a signature sound, a music track, a drive-by pitch, and a stationary pitch for our vehicles, and we need all the creative and production. Are there any questions?”

“I am very impressed,” said Kweku. “I like the two-in-one pitch with the adapter, which makes your product very versatile. What I would still want to know is, what is the character of the brand in terms of tone of voice? Before we could do the music, we would need to know more about that. Clearly the voice must be Ghanaian, but what kind of Ghanaian? How old? The music could range from traditional highlife, which is rather dated and conservative, to contemporary hiplife. Do you see what I mean?”

“Absolutely,” said Whit, “and that’s an excellent question. Right now I would say our sweet spot for customers is in the thirty-to forty-year-old range, but I know that’s still a big demographic, and we have many younger and older clients. So we need to think about that.”

“Another thing I would add,” said Kweku, “is that every Ghanaian has aspirations to be better than what he is. Even the person in the gutter today dreams of doing better. So I would not focus too much on the poor as a concept.”

“I hear you,” said Whit. “This is really very helpful.”

It was getting late and Whit was exhausted—too many meetings, too many late nights in the battery room, too many decisions, and too much fucking heat. Rose was staying with her parents in Accra that night; I took the driver’s seat for the haul back to Kof-town. The lights of Accra were twinkling on as I pivoted the truck around the hairpin turns up the Akwapim Ridge and around the promontory of Kitase, where the presidential weekend retreat called the Peduase Lodge hovered in fog over the capital. The lodge, a sprawling modernist slab with its own theater, zoo, poultry farm, and cricket oval, was built by Nkrumah in 1959 as a place to house, entertain, and impress foreign dignitaries visiting the newly independent nation. Unlike Accra’s Osu Castle, the president’s primary residence and the seat of government, this new building would have no colonial references, no imperialist baggage, no slave history. It was sleek and modern—a new, updated look for the new “brand” of Africa.

At least that was the idea. To me it looked like an oversized Rat Pack playhouse—too ungainly and vulgar even for Sammy and Dino, but maybe perfect for, say, Jackie Gleason. Still, over the years it had gained a certain notoriety. In 1967 the lodge hosted the mediation talks between rival Nigerian factions that resulted in the ill-fated Aburi Accord. (Biafra seceded anyway, plunging Nigeria into civil war and mass starvation.) But by 2002, Peduase, like many of the slave castles, was abandoned and in ruins—terrazzo floors cracking, roofs leaking, giant termites feasting on the custom cabinetry, and curtains “reduced to rags,” according to a firsthand report in the Daily Graphic: “There is nothing to write home about the pantry and the once magnificent fountain.”

Peduase Lodge was renovated under President Kufuor and is now in use again. Unfortunately, the motorway out of town that provides the only access to Peduase—the same road to the university in Legon and on to Koforidua—is in a semipermanent state of rebuilding, and traffic crawls over dirt and around detours night and day. When President Obama and his family came in July 2009 (his first state visit to a sub-Saharan nation), they stayed at the airport Holiday Inn.

Whit was snoring by the time we passed Rita Marley’s gated recording studio, just up the road from Peduase Lodge, and I drove the last, dangerous hour in tense silence, straining to focus on gutters and goats along the twisting pitch-black road. It was nine o’clock when we rolled through the gate of Koforidua’s Mac-Dic Royal Plaza Hotel for a relatively expensive but welcoming dinner of grilled octopus and tough steak.

“I think Ogilvy will want twenty thousand cedis to do something for us,” Whit said, pouring a glass of wine. “But I’ll give them five thousand.”

“And how will you convince them to take that?”

“I just won’t do it. I’m ready to walk away. But they want to do it. It’s good for their company, good for employee morale, good for their image, good for recruiting. They’ll do it.”

Even if Whit wasn’t ready to paint Ghana green, he was dying to paint Burro headquarters green. It was a largely symbolic gesture, since Burro did relatively little walk-up business, but Whit’s lease was up for renegotiation, and in Ghana the landlord typically pays to paint the exterior, so the timing was right. We had seen a green tint on a building in the town of Aburi that looked just about right; I took a picture of the Burro truck in front of the green building, and you couldn’t tell the difference. I walked around to the courtyard and asked the owner what the paint was. “Green Apple,” he said, showing me the can with the brand. Back in Koforidua, I found it in a paint store.

Jan arranged with a local crew to do the painting, but the landlord felt their price was too high and strongly suggested they consult his cousin Seth, also a painter by trade, for a “competitive” quote. Seth came over and met with Jan. “Do you have equipment?” she asked.

“Yes, I have all the equipment,” he said.

He got the job, but when he showed up to paint the façade of a building half the length of a city block, he had just one small putty knife, a couple of ratty paintbrushes, and a roller caked in dried paint. He had no drop cloths, no large scrapers, no masking tape, no cleaning supplies. He had no ladder.

“I will rent the ladder from the fire department,” he told Jan, for two cedis per day, and off he went to secure what was apparently the only ladder in town; fortunately the city’s cinder-block buildings rarely catch fire, but it does happen, given the haphazard electrical wiring that appears to be standard in Ghana. The few fires I had noticed over the course of a year all smelled electrical and blotted the sky with foul black smoke.

Meanwhile, Seth’s assistant showed up and introduced himself as a pastor.

“A pastor?” said Jan.

“Actually I’m a prophet,” he replied. Jan raised her eyebrows. “A minor prophet,” he clarified.

“We were hoping for a painter.”

He ignored her and went to work, perhaps already deep in revelation.

As the job progressed, it became clear that neither painter had received much divine inspiration with the brush. Both were slopping paint all over the veranda floor. Jan came out and noticed Seth was painting the spaces inside the decorative cinder-block balustrade, which were caked with years of urban grime.

“You can’t paint the dirt,” she told him. “You have to scrub off the dirt with a brush and water.”

“I don’t have any water,” he replied. Jan brought him a bucket and a brush.

“If I wash it, I will have to wait for it to dry, and that will slow me down,” he said.

“I don’t care,” said Jan. “The paint won’t stick to the dirt.” And she took his scraper and showed him how the paint he had applied slid right off.

“Oh, I get you,” he said. But the next time she came out, he was still painting over the dirt.

By the end of the weekend they thought they were done and returned the ladder, but when Jan came back from Accra on Monday she noticed lots of missed spots and mistakes. Seth went back to the fire department to reclaim the ladder, but it was in high demand and someone else had rented it. Eventually the work got done; the total cost was seven hundred and three cedis, including paint. To no one’s surprise, the new green-and-black building attracted a wave of walk-in business. More important, it established the brand in downtown Koforidua. One day Precious pointed at the façade and said, “Auntie Jan, it’s a battery!”