I never cared about Africa. I never wanted to join the Peace Corps, raft the Zambezi, haggle in Fez or climb Kilimanjaro. My favorite Ernest Hemingway stories were set not in the blistering Serengeti but in familiar and temperate locations like Italy, France, and Michigan—places where insects are merely an annoyance and steaks are well marbled. I have no interest in a yam-based cuisine. It would never occur to me to attend a benefit concert for Africa. Except for a brief period as a boy after seeing the Howard Hawks film Hatari! I never even wanted to go on safari. Tanzania? I once interviewed Chuck Norris at his home in Tarzana, which sounded close enough.

But my brother Whit was starting this business in Ghana called Burro, renting batteries to people who earn a dollar a day, in a country with annual inflation exceeding 20 percent and a long history of military coups followed by firing squads. It sounded like an exceedingly bad business idea—in the pantheon of turkeys, I pictured it right up there next to the Edsel and New Coke—which intrigued me.

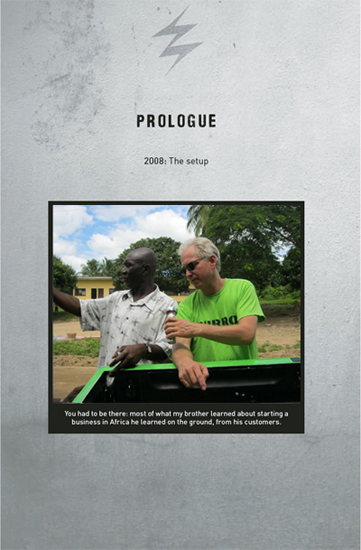

As a young man Whit had lived in Western Africa for several years, first as a student and then working on various aid projects, and he always believed that while many worthy charities are making huge differences for Africans, ultimately the marketplace—not government handouts or benefit concerts—would create lasting solutions to African poverty. Recently that’s become a timely, even trendy, idea. From Davos to Seattle, in Zambia and New York, academics and business titans have been talking a lot about how to help poor people by giving them useful stuff to buy, and in the process creating enterprises that are sustainable, thus generating employment. But talking about bringing business to Africa is not much different than attending a benefit concert—it makes you feel good and requires no sacrifice. Saying good-bye to your family and touching down on an African tarmac with a business visa is quite another matter.

The touchdown is what intrigued me.

I was also fascinated by the risk—here I mean business risk, as opposed to the broader African risk of contracting a new strain of polio or having body parts removed by rebels—because I like few things more than tormenting my brother about his crazy start-up schemes. In 1997 he teamed up with Richard Tait, a former Microsoft colleague, to create a new board game. “A game where everyone shines” was the essence of Tait’s original idea, and the two came up with Cranium. Whit hired me to write some of the questions for the first edition, a job I engaged with enthusiasm, but in my clearer moments I was lukewarm to the concept. With its mix of trivia questions, charades, word puzzles, whistling, and clay sculpting, it seemed too unfocused, too hard to get. I felt sorry for my brother because I was sure no one would buy the game.

Which goes to show how much I know about board games. Cranium, of course, became the hit game of the new millennium, embraced by celebrities like Julia Roberts and sold in Starbucks like brain food. Richard and Whit, “the Cranium guys,” became minor celebrities in their own right, along the lines of Ben and Jerry. They were in People magazine. They made the cover of Inc. magazine. They were even featured in one of those Dewar’s Scotch ads—my sloppy kid brother tricked up to look respectable in a Calvin Klein suit, Hugo Boss shirt, and even a necktie.

Over the years Cranium introduced many new games, and I was certain most of them sucked. I told Whit, “No one will buy that; it’s got too many moving parts.” Or “Kids will choke on those dice.” Or “My cat could win this game.” Many of them went on to be named Game of the Year at the annual New York Toy Fair. What did they know that I didn’t?

It turns out that nobody knows anything. Innovators trust their gut much more than their brain, but most people aren’t comfortable putting so much stock in stomach fluids, so we cling to the top-down, brainiac theory of innovation. We think of Bill Gates as a nerdy genius, which he probably is, but think about it: there had to be something in his gut to make him drop out of Harvard and start Microsoft. A truly brainy geek would have finished his studies.

In January 2008, Gates addressed the Davos World Economic Forum on the subject of what he called “creative capitalism.” In his speech Gates called for businesses to develop innovative products that would serve consumers on the lowest rung of the economic ladder. He pointed out that charity wasn’t enough to lift people in the developing world out of poverty. They needed the power of the marketplace to invent solutions that would improve their lives. Come up with the right product at the right price, said Gates, and the poor will beat a path to your door. He described this model as a win-win situation: the poor improve their lives and become modern consumers, while companies make money and gain recognition. In some cases, he noted, corporations might even apply their third-world innovations to first-world markets. “This kind of creative capitalism matches business expertise with needs in the developing world to find markets that are already there, but are untapped,” Gates said.

It sounded great. I pictured Indiana Jones riding shotgun with a spreadsheet across the savannah, Willy Loman shuffling through the casbah. But if they were out there, they weren’t blogging, or hiring public relations agents. Maybe they only existed in speeches and polemical textbooks.

Whit knew a few people out there on the advance guard, both Westerners and indigenous pioneers, looking for new solutions in the developing world. But few were as passionate as he about applying conventional business approaches to financing and investors. Most were seeking some sort of start-up subsidy from the nonprofit realm, and very few were attracting profit-motivated investors. Nor did they seem as focused on brand development as Whit was. What’s more, no one was documenting what it was really like on the ground, village to village.

The more I tried to learn, the more I saw my own brother as being pretty far out there on the edge—maybe one of the first few in a new movement. Maybe it would only last a moment. Maybe it would change the world. Either way, I wanted to be there, and not just because he was my brother. With the global economy imploding, jobs disappearing, banks tanking, and abandoned swimming pools across Southern California turning green with algae, I wondered if doing business in the developing world could do more than help the poor. I wondered if the poorest people could teach the rest of us how to live better.

In his 2007 best seller Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future, Bill McKibben argued that some bedrock tenets of modern capitalism—growth is good and more is better—are unsustainable in a world of finite resources and restless masses. He made a pitch for a new capitalist paradigm that separates more from better, and that nurtures small, local markets that might seem “inefficient” by conventional measures but may ultimately be more sustainable.

It’s possible to imagine Ghana as a field test for some postmodern, localized, McKibben-style capitalism. More than half the population still lives off the electrical grid. Many citizens have never ventured farther than the nearest market town, perhaps half a day’s walk from their own village. If you were looking to test a new paradigm for capitalism in a country of small, inefficient local markets, this could be paradise indeed. But my wife wondered if Africans need more “stuff,” as opposed to, say, electricity and good government. Despite our good intentions, were we in fact just making the world safe for Walmarts in Rwanda?

“Your wife is a Waldorf kindergarten teacher,” said Whit when I brought this up over the phone one day in late 2008. (He had arrived in Ghana that summer to start the business.) “She plays with sticks all day and doesn’t let kids use video games. Of course she’s worried about consumerism in Africa. I think she needs a hobby, something high-tech like laser-guided wood carving. I mean, she spends all her time around six-year-olds and you; imagine the warped perspective. Seriously, these people are so far away from the problems of materialism, at least out here in the bush. What I’m doing with Burro is nothing but a positive influence. Good God. There are shopping malls in Accra where flyers offering credit to anyone with any sort of job for any sort of purchase are being distributed en masse. Countless, pointless, consumer offerings are in play. They’re plying all imaginable wares to the discretionary dollars of Ghanaian elites, and these people have no shopping chops; they’re like lambs to slaughter. Burro is about supplying affordable, productivity-enhancing goods and services to low-income people, and doing it profitably so that we can continue to do so without infusions from governments or charities. How in God’s name this might be a bad influence escapes me completely.”

“I’d be careful how you invoke God over there,” I said. “Those people are seriously religious, and they have voodoo.”

He ignored me, which was becoming a theme in our conversations. Although I once managed a daily newspaper with an annual news budget of six million dollars, Whit generally assumed I had the business acumen of a cloistered nun. “Look, I’ll grant you that Ghana is a relatively affluent nation by African standards,” he went on. “It comes in tenth in per capita GDP in the sub-Saharan countries, if you don’t count island playgrounds like the Seychelles. The World Bank considers it one of the most vibrant economies in Africa, which is one reason we’re here. But it’s all relative. All that basically means is that nobody’s literally starving—for the moment. But malnutrition is rampant. Clean drinking water is a distant dream. The average adult has less than four years’ formal education, and a fourth, maybe more, are illiterate. These people are a long way from your hamster wheel.”

“I’m thinking I might be nuts to go over there,” I said to Whit.

“Not my call,” he said. “In the world of Burro we must each make our own risk assessments.”

No, it wasn’t Whit’s call, but Africa was calling. I saw an opportunity to reconnect with my brother, a process that had begun a year earlier when our dad died suddenly and we were thrust into funeral planning. Besides, I had clearly misjudged his Cranium venture, and here was a chance to annoy him more intimately on his latest scheme. And as the oldest child, I was feeling the jitters of succession: with my father gone, there was no one left between myself and mortality, no buffer zone anymore. I was next. How many chances would I get to do something significant and crazy with my kid brother?

And while late 2008 may not have been the best time to start a new business in Africa (where local economies were crippled by the global recession), it seemed like a good time to be paying attention to that other half of the world. It’s not like Whit was doing volunteer work, but his success depended almost entirely on his ability to understand what poor Africans needed and wanted; he would need to listen carefully, which is always a good place to start. As for me, all of my community-building efforts to date had been largely in my own backyard: helping at our kids’ schools, the church soup kitchen, a grassroots conservation group in my town. These were worthy efforts, but largely self-centered. Except for the soup kitchen, they all measurably improved my own family’s quality of life.

We had moved to Maine ten years ago, after many years in New York and Los Angeles, hoping to raise our children in an environment relatively free of material clutter. The fact that Maine is one of only three states that outlaw billboards did not really play into our decision, but it did portend a place of kindred spirits. Over the last decade, however, the Internet has essentially turned every American home into a shopping mall; billboards or not, there is no escaping the consumer culture if you live anywhere within a five-digit zip code. So I saw Africa as another leap away from all the stuff we buy, and I wanted to know what that felt like. (Other than a few elite enclaves, Ghana has no door-to-door mail service, and post office boxes have long waiting lists, so ordering physical goods on the Web is simply not an option for most citizens.)

Little did I know that any given stretch of back road in Ghana boasts more liquor billboards than the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Or that in Africa, people make money by agreeing to have their entire home painted as an advertisement, which actually looks pretty cool. So it wasn’t Bali Ha’i. But it was a broad new horizon.

I don’t want to give the impression we lived like hippies. In fact, just pondering the plan, I could see my comfortable life fading like a Saharan mirage. I already saw Whit abandoning for months at a stretch his wife, Shelly Sundberg (a program officer at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) and their two teenagers, Cameron and Rachel, back home in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood; paying two years’ rent on an incredibly noisy seven-room office and living space in a provincial town with running water two days a week; investing hundreds of thousands of dollars of his own money; convincing Jan Watson, his former head of operations at Cranium, to quit her job at Microsoft and join him in Ghana; and hiring a full-time local employee with all the state-required benefits. I had a nice home in Maine, two amazing boys, and the world’s greatest wife, plus a sailboat. What was I thinking?

There wasn’t much research we could fall back on. My brother and I started a reading list, everything from the catalog for a 2007 exhibit on third-world product design at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, to histories of Africa, its leaders, colonizers, and explorers. Yet the literature on grass-roots social entrepreneurship was thin, once you got below all the breathless hype. There was no Idiot’s Guide. Consider the reaction to Gates’s Davos speech. Perhaps not since the Gettysburg Address has a short talk been so intensely analyzed and parsed. (At 2,765 words, Gates’s speech was ten times as long as Lincoln’s, but still brief by the gaseous standards of most executive presentations.) Yet at latest count, googling bill gates creative capitalism yielded about 141,000 entries. This is not surprising as Gates pretty much invited the world to come up with solutions to the problem of making capitalism work in the developing world. Furthermore it wasn’t completely clear what he meant by creative capitalism, since plain-vanilla capitalism would seem to be creative by definition. So the floodgates opened.

A notable example was the book Creative Capitalism, a collection of online essays assembled by Slate editor Michael Kinsley in response to the Gates speech. There were some nuggets of wisdom, notably from economist William Easterly, who has spent a lot of time working for the World Bank in poor countries. “You have to work very hard to figure out what the poor want and need,” he wrote in the book, “and you have to work very hard to meet those needs under local conditions [my italics].”

Good point. But none of these writers offered any clue as to what it’s really like to do so. How could they? Of the forty-two contributors to the book, only one—Loretta Michaels of HMS Wireless, which develops Internet technology for poor countries—was an actual businessperson doing deals on the ground in grubby foreign places. All the other contributors (besides Gates and Warren Buffett, both interviewed briefly) were professors, journalists, consultants, and “fellows.” I have nothing against these professionals. I am one myself. But anyone starting a business in the developing world doesn’t need navel-gazing economists and op-ed theorists. He needs a survival kit.

What kind of business models work in really poor and possibly dangerous places, and who invests in them? Can you find competent employees? Don’t these countries have absurdly bureaucratic regulations that hamper start-up business ventures? Are you even allowed to repatriate profits? Is there FedEx? What happens when the dictator dies? Aren’t there crocodiles and snakes? On these and scores of other pressing real-world questions, the experts were silent, and the only sound coming from the developing world was the hum of the tsetse fly.