The idea for Amor y Tacos has been brewing in my notebooks for almost a decade. After publishing a book of traditional Baja Mexican recipes, and another of Mexican-inspired vegetarian food, I knew I wanted to create a “party book” of cocktails and simple, delicious food, reflecting what was happening with Mexican food on both sides of the border.

Reading back over ten years of my research journals, I found myself intrigued by the new angles on Mexican food that kept popping up in my notes, especially in the areas of tacos, antojitos (little bites), and cocktails. I started to see a new kind of Mexican food with a streetwise spin that was fun, exciting, and unexpected. I found bartenders acting like chefs; I began to see old standards done in new ways. Not fusion, but a fresh take on traditional preparations. It was food that was clearly Mexican but rethought, rediscovered, newly appreciated. I don’t recall whether the light went on with my first chamoy margarita, or my first taco vampiro. But after my first visit to El Taco de la Ermita in Tijuana, I knew this was the direction I wanted to pursue, not least because it is rapidly becoming an even a bigger trend in the United States.

This next wave grew out of la cocina nueva—Mexico’s answer to nouvelle cuisine and California cuisine. In every major city, especially in Mexico City, cutting-edge chefs were cooking remarkable food, and their ideas were filtering into the broader cooking community. Mexican expats who moved north to work in restaurants brought ideas with them. American chefs, finally listening to their cooks, were traveling and seeing Mexican food in a new way. Good-quality Mexican ingredients became widely available at last. Tequila suddenly became chic. It was a perfect storm.

Mexico’s culinary heritage is ancient but far from static. Modern Mexican food can be stunning, precocious, ground-breaking—yet still recognizably Mexican, confidently walking the tightrope between a bone-deep understanding of tradition and the kind of head-turning, self-conscious innovation that is hip to the point of irony. You might think you know what a taco is—of course!—and yet the taco keeps evolving. A margarita is still a margarita, though flavored and tweaked in delightful new ways. Even the dreaded chips-and-salsa yawn is giving way, at last, to antojitos, wonderful little bites that showcase the cook’s sophistication. The trend is definitely to simplify and emphasize freshness. Best of all, most of this food is based on the very easiest preparations: street style, quick and fast.

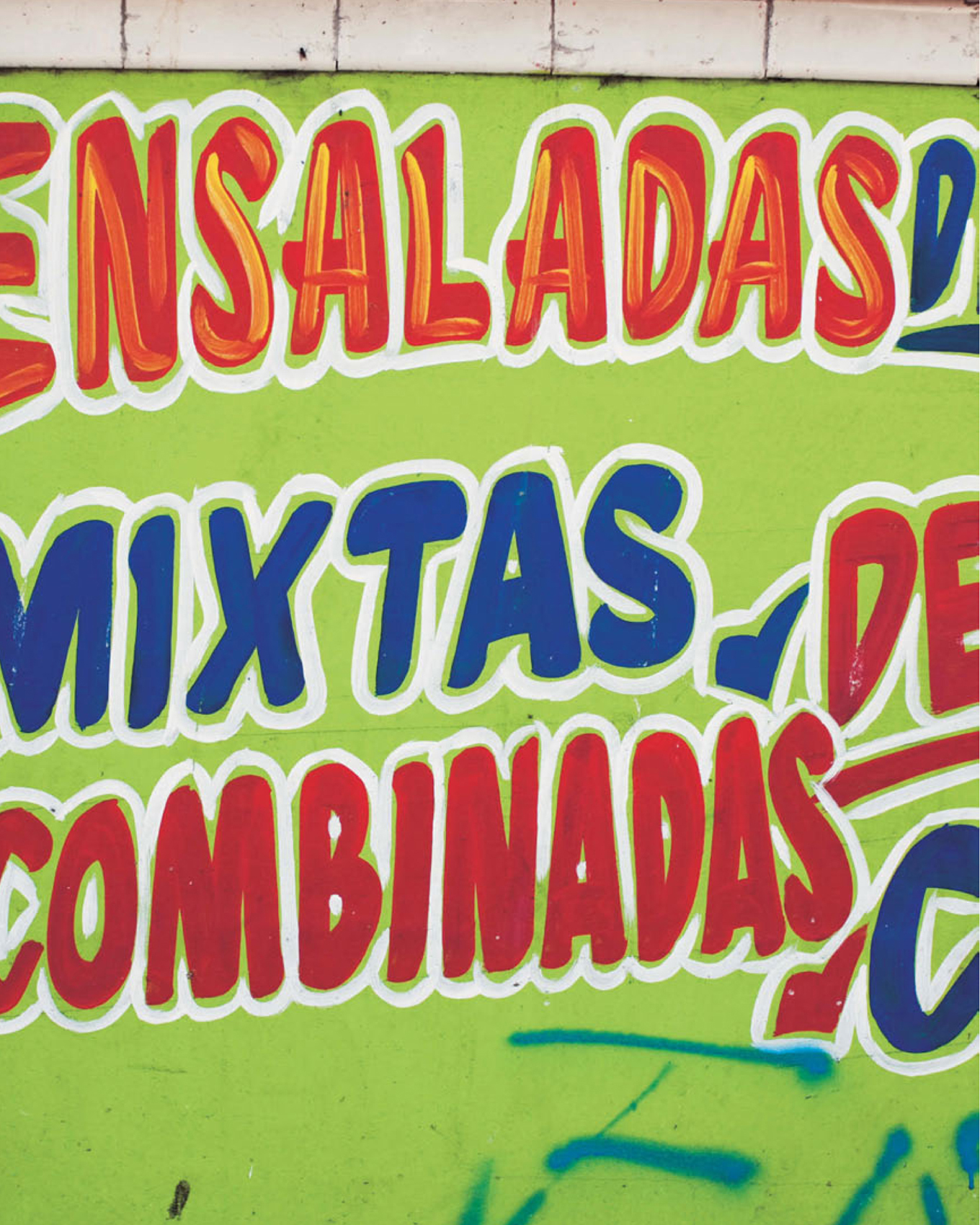

I wanted to present this new wave of Mexican food against the background of a real Mexican city—colorful, gritty, modern, and hip. My view of Mexico is strictly street-level. Sombreros and serapes and molcajetes are all very well, but these neighborhoods are alive: intriguing botánicas, sleekly modern Mexican design, street markets and vendors, folk art, stand-up food stalls, bubbly Mexican pop music and wailing norteña, wild crazy colors on walls and doors. I also wanted to share my love of funny, wry dichos—Mexican sayings. That’s a tall order for a little book.

My first book, ¡Baja! Cooking on the Edge introduced readers to a kind of Mexican food many didn’t know existed: the food of coastal pueblos in one of the world’s most beautiful and remote areas. I hope that Amor y Tacos will introduce you to a new kind of Mexican food and attitude and that you have as much fun exploring these new ideas as I did finding them.

As a classically-trained chef who has written three books about Mexican food and the border region, I’m often asked, “Why Mexico? And for chrissakes, why Tijuana?” Sometimes I answer grandly, as some do about Everest, “Because it’s there.” (Barely 15 miles from my front door, as a matter of fact.) But the true answer is that after living in the sterile beehive of Southern California, I’m drawn to the honesty of a real city. I like the feel of being in a community where the sidewalks are crowded, you can shop and haggle, talk and laugh and stand up to eat next to strangers on the street—just like that! Like the medinas of North Africa that I visited years ago, that were the hearts of their community, Tijuana has a heart. A tough survivor’s heart; a streetwise, take-no-prisoners kind of heart, but a heart you can feel, and certainly one you can come to love.

Tijuana itself is unlovely but full of life, a great, humming beast that sprawls across the dry concrete riverbed from the neatly planned streets of San Ysidro and Chula Vista. San Diego and Tijuana are like the many-headed ogre in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, sharing a body but occasionally fighting with itself. It’s impossible for either city to escape the pulse of the other.

I’ve learned to appreciate the strange, funky aesthetic of this hybrid place—a noisy jigsaw of broken concrete and new high-rises, with one huarache’d foot in the past and the other on a jet ride to the future. It is alive and ever-changing, gritty, noisy, rude, colorful, and lively, full of unexpected visual gifts around every corner. A basement stairwell painted in vivid purple and yellow zebra stripes, leading nowhere. Statuettes of the busy dead, dancing, laughing, eating, and fornicating—in-your-face folk art with deadly meaning, not tourist junk. Everywhere, in odd corners, one sees loving, handmade shrines to the sweet-faced Virgin of Guadalupe, with her mantle of stars and roses, or to a local santo draped in rosaries and dead blossoms, dusted with the ashes of copal incense. Inside an eerie botánica perfumed with beeswax and incense is a semipagan mixture of herbs and potions, skeletal icons, statuettes, and good-luck charms. Outside, a string of illegible words and numbers, exquisitely rendered in spray paint, undulates down an alleyway, making a breathing dragon of a concrete wall, broken by an unused doorway framed with decades-old tiles in faded swirls and flowers.

One such neighborhood of Tijuana is home to El Taco de la Ermita (known to border cabbies, if you go, as Los Salseados), a simple open-air taqueria down a narrow street in the La Mesa area of Tijuana, just off Agua Caliente. There are hundreds of taquerias in Tijuana; you’ll know you have the right place when you see a tiny place packed three deep and spilling into the road, and when you see well-dressed and wealthy tijuanenses (not the meekest of customers) waiting patiently for an hour or more for a precious seat. It is the only taco stand I know of that uses a uniformed security guard to keep order among its patrons.

Owner–chef auteur Javier Campos rules over a tiny outdoor kitchen built around a full-sized tree, something you can get away with only in Mexico. The best place to sit, once you elbow your way in, is the taco bar that wraps around the corner where Chef Javier works. To his left are an array of salsas in small bowls and squeeze bottles, often as many as forty different types. To his right are a small grill and a plancha, and one of those peculiar Mexican cooking surfaces with a concave and convex area for frying and draining tripa (tripe). While he cooks, he discusses the night’s choices with his guests. (There is a menu, but no one orders from it.) Then, with speed and precision, he cooks, assembles tacos, dollops salsas, and peels and slices impossibly perfect avocados to place on top of each taco. He clears plates, chats amiably with everyone, barks orders at his cooks, and keeps an eye on the till and tiny table area.

The tacos are remarkable by any standard. Shrimp tacos with roasted rajas (poblanos and onions charred and sautéed with garlic and epazote) come heaped with sautéed mushrooms and no fewer than three salsas from the array at his side. Campos swiftly toasts a circle of shredded Jack cheese into a crisp golden frico (a thin disc of fried cheese), stuffs it with lobster, rolls it and tucks it into a freshly made corn tortilla with two creamy salsas, one very hot, and a sliver of perfect avocado. Slices of filet mignon are topped with garlicky shrimp and cheese and rolled up with habanero chiles and more unknown (but delicious) salsas. His tour de force is another Jack cheese frico, this one stuffed with chicken and pineapple, then topped with not one but three different fruit salsas and a sprinkle of chopped nuts. But ask for a classic, such as tripa, and his execution is equally flawless. The tripe is crisp and chewy, for he has been carefully cooking it for over an hour. It is served simply, with a smooth salsa verde and raw onion, and it is delicious.

El Taco is a not an isolated phenomenon, although it is better than most. Many Mexican chefs are experimenting in similar fashion. Most striking at El Taco, apart from the sheer number of original salsas, are flavors warmly traditional, yet worlds apart from the standard taco. Campos’s ingredients are often more luxurious than the average street taco—he likes filet and lobster—but he also is a master of classic salsas and ingredients like lengua (braised tongue) and tripa. His insistence on the best ingredients, perfectly fresh and chosen that day, is fanatical. Every taco is created when ordered and served with the perfect combination of salsas. And instead of handing patrons a bare taco, to be fixed al gusto, Javier assembles his array of salsas and creates what he thinks is the best finished product for you, a big step away from the usual taco experience. Does he know best? Absolutely. He plays those salsas like a jazz musician plays notes.

When I first began working with Mexican cooks, I quickly learned that they tease each other all day long. Nicknames are casual, short, and rude: el pelon (baldy) for the guy who is vain about his thinning hair, el chapparito (shorty) for a small man in tall heels, el gordo (fatso) for the biggest belly or the greediest eater. I worked with several el changitos (apes) and one la princesa who happened to be male. I was called la flaca—the skinny one, which had other implications I won’t go into here—and I was relieved to get off so lightly.

In a similar vein are the simple folk sayings known as dichos—often funny, sometimes bawdy, and frequently wise. There are hundreds of them, and everyone has his or her favorites. Many rhyme, the better for a semiliterate population to remember them. The first dicho I ever heard was along the lines of “if you’re lucky in love, don’t make bets”—sage advice on rolling the dice (or taking a mate for granted). When I came to work with a cold, I was advised to take a drink of mezcal or tequila because “por todo mal, mezcal; y por todo bien, tambien”—mezcal for all ills, and for all good, too. I learned many others: one cook, they told me, was so cheap he wouldn’t buy a banana because he’d have to throw away the peel. He was so cheap he wouldn’t wear glasses to read the newspaper. And so on. The cooks used to say “poco a poco se anda lejas”—“little by little will get you far”—which proved to be good advice for this author. I still love to hear a new dicho.