CHAPTER 22 STARS AND STRIPES

NEW YORK, 1942

JACK DEMPSEY’S BAR IN MANHATTAN’S Brill Building was packed and thick with cigar and cigarette smoke, the floor sticky with spilled drinks. You might not have even known there was a war on except for the darkened marquees and office buildings in the Midtown neighborhood. Dempsey’s signature orange neon sign was turned off, but the loud partying continued behind tall curtains pulled shut to hide the lights inside. Harry Donenfeld spent plenty of free time here—and his work time, too—laughing and joking with his hotfoot buddy. Dempsey was often at the Times Square institution, seated at a corner booth smoking a cigar, signing autographs, and posing for photos with fans. Harry also liked to hit nearby Toots Shor’s on West Fifty-First Street, with its circular bar and checked tablecloths, where Superman’s number one fan, Joe DiMaggio, hung out with his Yankee teammates until he enlisted in 1943. Toots Shor’s was once described as a locker room with table service. Wives were not welcome, but other women were.

Sometimes Harry’s wartime partying got out of hand, like the night he was arrested by the Miami police for driving the wrong way down a one-way street and not having his identification with him. When he told the cops who he was, the publisher of Superman, they didn’t believe him—until a reporter recognized him. An officer called the Versailles hotel, where Harry had been staying, and a friend ran his wallet over to police headquarters. The cops apologized and Harry took down a long list of their kids’ names with a promise to send them free copies of the comic book. “If I ever get in jail, I hope it is in Miami,” Harry said with a slur. “I’ve never been shown such hospitality.” Hiccup.

There was the time he disappeared for an entire workweek. Lost weekends were for amateurs. Harry was gone for five whole days. No one knew where he was. Not Jack. Not Gussie. Not even Sunny. When Harry finally turned up, he told everyone he had been in Los Angeles, partying with Chef Boyardee. He had, in fact, been on a drinking binge, poolside at the Beverly Hilton hotel with French matinee idol Charles Boyer, shagging everything in sight.

Harry’s hundreds of employees were fully aware of his reputation, but they loved him for it. For his fiftieth birthday, the company published a mock newspaper called The Daily Snooze, joking about his love of drinking and featuring a comic strip of Harry spanking Superman. Every month, Independent News, Harry and Jack’s parent company that published and distributed all their magazines and comics, ran a nationwide newsletter announcing not just sales numbers, but births, marriages, and deaths within the publishing “family.” Harry was always a featured character. But top-earning distributors, dealers, and wholesalers were profiled as well—not just from DC Comics in New York, but from the vast network across America. A Winchell-like column dished the company dirt. There were comics written by Jerry and Joe just about the business—Superman rescuing snowbound copies or fixing the broken presses—and even poems about traveling salesmen and the troops in Europe. At the bottom of the page was the Superman Service Flag, with stars that showed how many sons of the distributors and wholesalers were serving in the war and how many had died.

In February 1942, Clark Kent tried to enlist in the military, but because of his X-ray vision, accidentally reads the eye chart in the next room and fails his exam. The following autumn, the words “Truth, justice, and the American way” were added to Superman’s job title as part of the radio show. Superman was no longer an intergalactic citizen but a representative of the good old US of A. And the Nazis were on his hit list.

In syndication, Jerry and Joe gave the troops—and their kid brothers and sisters at home—a Christmas surprise. In a series that ran late November through December 1942, Mussolini, Tojo, and Hitler kidnap Santa Claus from his North Pole workshop to try to convince him to join the Axis powers. “Herr Claus,” says Hitler, “I’m told that you are of Teutonic descent—in fact were once known as Kris Kringle. As a true German, preach the doctrine of the new order and you can become an important cog in our set-up.” Santa, tied in chains, rebuffs the dastardly trio. “I am not a German, nor am I French, or American or any other nationality.… I live in the hearts of all good men,” says a defiant Santa, who is then sent off to a concentration camp. Before Christmas can be canceled, and Santa murdered, Superman flies to Berlin and saves him, then helps to deliver his gifts.

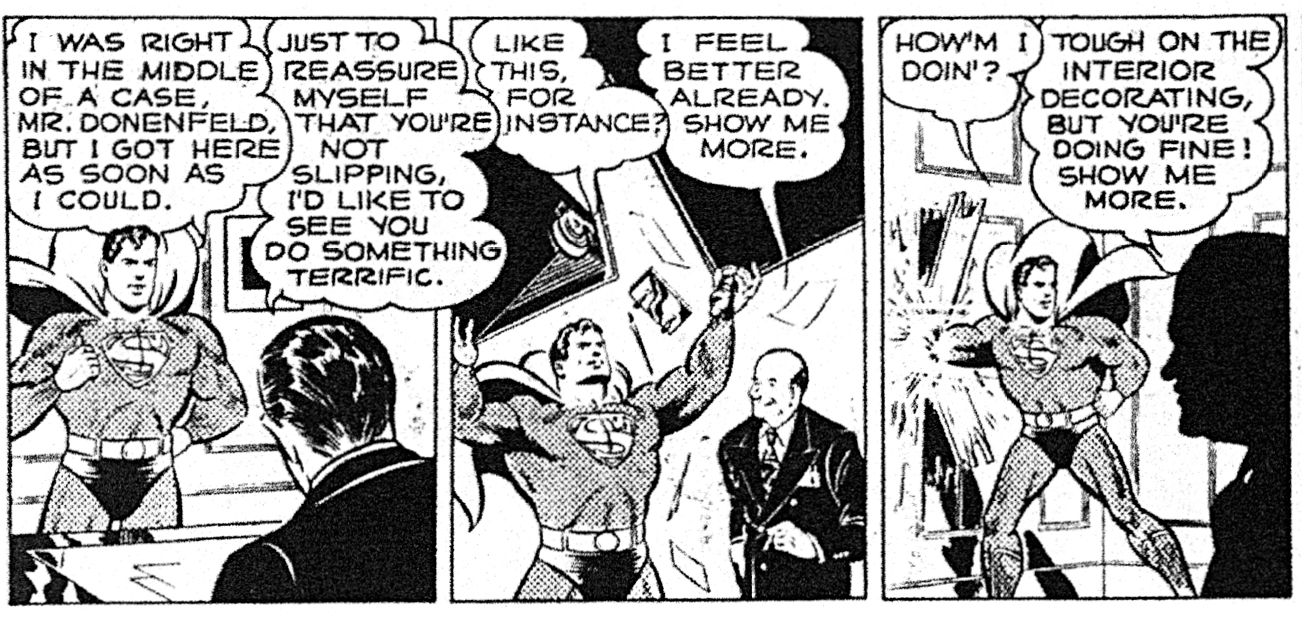

HARRY SHOWS SUPERMAN WHO’S BOSS

For Harry’s growing staff of comic artists, Hitler became a staple, gracing more than one hundred covers. There was one featuring Goebbels, and another, much later, with war victims being led to the ovens. In one strange coincidence, George Reeves—who would play Superman on television nine years later—starred in the 1943 war film So Proudly We Hail! At one point in the movie, a group of kids is discussing a Superman comic with one of the army nurses.

Thanks to young GIs’ reading habits, and Harry’s ability to export magazines overseas, the sales of comic books doubled from 1941 to 1944. Superman was cheering the troops on, but also reminded them of home and simpler times. By the spring of 1944, comics made up a third of all magazine sales, surpassing news magazines, women’s magazines, and even movie magazines. Despite wartime paper and gasoline shortages, Harry and Jack put out twenty-four different publications—everything from Ha Ha to Mutt and Jeff to Picture Stories from the Bible. Harry’s newest title, All-Funnies, sold out its first issue nationwide.

Harry and Jack were throwing all sorts of comic book characters out into the world to see who would fly: Starman, Hourman, Boy Commandos, and others forgotten by history. But now and then, one would soar, like Batman and the patriotic Wonder Woman. Some were created in-house and so belonged outright to Harry and Jack. Bob Kane, the freelancer who invented Batman, would hold on to his rights after seeing what had happened to Jerry and Joe. Their contractual misstep—often called the original sin of comic books—was a lesson for every comic book creator that ever followed.

Though Jerry was making a great living, it still irked him that Superman no longer belonged to him and Joe. One afternoon, while Jerry was in the Grand Central Palace offices, one of the staff members took him into a stairwell and quietly told him that Harry and Jack were making millions through the radio show and merchandising. (Though the comic book cost ten cents, the Daisy Superman Krypto-Ray Gun Projector Pistol cost ten times as much. And Jerry and Joe weren’t seeing any of that profit.)

Jerry had a sizable $20,000 nut stashed away in the bank, but he began asking—rightfully so—for more money. In response, DC’s editors told him and Joe their work was subpar. In one letter to Jerry, editor Whitney Ellsworth accused him of being “very complacent about the guy you invented.” Superman looked like a different character in nearly every picture and became increasingly cruder and cruder, said Ellsworth. Though he complained about Superman’s hands and actions, Ellsworth was most upset about the superhero’s tight red shorts. “I have written you repeatedly about how the manner in which his jock strap is drawn, and absolutely nothing is ever done about it.” Ellsworth also complained to Jerry that he needed to explain to Joe and the other artists how to draw a pretty girl. (Though Jerry was married, Joe would be single for thirty-five years.) Jack complained that Lois Lane was starting to look like a witch, her hair a veritable rat’s nest and her clothes dowdy and unfashionable. Jack “suggests Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper’s Bazaar as likelier spots for dress research,” wrote Ellsworth. “The gal ain’t being done right.” Unless something changed, other arrangements would need to be made. “Altogether,” one letter read, “the situation is serious enough to warrant your doing some real worrying.”

Though Jerry constantly came up with new characters, Harry and Jack told him to just concentrate on Superman. As early as 1938, Jerry had started pitching Superboy, the adolescent version of Superman, tracing his life growing up in Smallville. But his bosses rejected it. Jerry resubmitted it. But they rejected it again.

Jerry pestered and pestered Jack for more money. And, of course, he and Joe were owed much more than they were receiving, not just for Superman but for all the superheroes they inspired, superheroes that continued to rake in the cash for DC Comics for decades to come: not just Wonder Woman and Batman but the Flash and all the spin-off villains from Superman. In 1942, Superman hit the big screen, starring in ten-minute animated shorts created by Fleischer Studios that would play before the feature film. Harry assured Jerry and Joe that the shorts cost more than they made; they didn’t.

Jerry went about asking for money in such an irritating way that Jack and Harry couldn’t stop bullying him. For instance, he wrote to Jack and asked him for $500. Jack replied that he had just sent him a check. But Jerry told him he had $19,500 in his account and wanted to make it an even $20,000. Jack reluctantly gave it to him. Jerry’s superpower, it seemed, was being super annoying.

Fearing Jack and Harry would give them the complete shaft, Jerry took his frustration out in subtle ways. A Superman story from the winter of 1942, which featured a cover of the superhero holding an American eagle on his forearm, was a master class in passive-aggressive behavior. Jerry’s plot involves a young inventor whose rights to his fire-extinguishing powder are stolen by a slick promoter. When the promoter’s house catches fire, Superman forces him to give up the rights before agreeing to put out the flames.

A few months later, an unmasked villain in Superman exclaims, “Nobody knows me! I wanted to be a celebrity—the creator of a famous comic strip: but no one would buy my strips.”

There were rumors that DC Comics had pulled strings to help keep twenty-eight-year-old Jerry out of the army, but after Jerry’s barely disguised attacks and constant complaining, some say Harry put in a call and had him drafted. Joe’s deteriorating vision kept him out of the military, but Jerry started serving in 1943. On leave two years later for the birth of his son, whom he named after his father who had died of a heart attack in that Cleveland robbery so long ago, Jerry again submitted Superboy for publication. But DC ignored him.

With Jerry stationed in Hawaii writing comedy columns for Stars and Stripes, his Superman duties were handed over to DC writers Don Cameron and Bill Finger, Batman’s co-creator. Jerry would submit the occasional Superman script to the New York office. But while he was away, Harry and Jack took his old script for Superboy and made Joe illustrate it, without ever telling Jerry or paying him for the rights. Not knowing what to do, a panicked Joe sent a copy of Superboy to Jerry in Hawaii. Jerry was understandably furious.

Like Jerry, Harry’s son, Irwin, was drafted as well. But with Harry’s pull he was sent only as far as Biloxi, Mississippi, to serve as a mechanic in the Army Air Corps. He boxed while in the army because he knew that boxers got weekends off. Irwin, who would go on to work for his father as editorial director, told people years later that he fought a lot of guys in World War II, but they were all Americans. And he was good, too. Maybe not as good as Jack Dempsey, but a good bet to win.

Harry visited him in Biloxi and was treated like royalty, the entire base marching out in formation to greet him. When the commander asked Harry what he wanted for lunch, Harry asked for a pastrami sandwich, much to Irwin’s dismay.

“Pop,” he whispered, nudging him. “They don’t have pastrami in Mississippi.”

But somehow, somewhere, the commander found Harry a pastrami sandwich.