CHAPTER 37 NIGHTS OF HORROR

QUEENS, SEPTEMBER 15, 1954

THE BEGINNING OF THE END came for Harry Donenfeld on the very same day that Marilyn’s dress blew up.

A team of New York City detectives descended on a small print shop across the East River in Richmond Hill, Queens. The quiet tree-lined neighborhood, tucked deep inside the borough, was a world away from Manhattan, unused to crowds or flashy police raids. The respectable Italian-, Irish-, and German-American families living in their modest two-story homes had no idea what had been going on in the Pilgrim Press offset printing operation all summer long. In a basement near the last stop on the elevated A train, twenty-seven-year-old Eugene Maletta had been churning out an edgy comic book called Nights of Horror. Maletta, caught in the act, was arrested for selling and distributing obscenity, his metal printing plates confiscated. A group of seventy-five detectives then fanned out across the city, seizing copies of the controversial comic book.

Though Maletta’s horror comic had a limited run of a few thousand, all of New York had heard about it that summer. Horror comics had been gaining in popularity in America in the 1950s, providing cheap—seemingly harmless—thrills to teenage boys and adults alike. But screaming headlines that August told of a group of teenagers who were inspired by Nights of Horror to launch a crime spree throughout Brooklyn, horsewhipping girls, setting a homeless man on fire, and killing two others. Until Marilyn arrived on the subway grate, those murders were all anyone could talk about.

The accused teenagers were a bunch of Jewish kids from Williamsburg. Many of the poor Jewish immigrants who had settled on the Lower East Side in Harry’s day had made the short journey across the Williamsburg Bridge, buying houses and creating a comfortable middle-class enclave. How could such good Jewish boys be led astray? In the months leading up to their trial, parents not just in Brooklyn but all across America were asking themselves, “Could this happen to my kid, too?”

The leader of the Brooklyn Thrill-Kill Gang, as it came to be known, was a tall, skinny eighteen-year-old redhead named Jack Koslow, who said the attacks were part of “a supreme adventure” and an effort to clean up the city streets of bums. His seventeen-year-old buddy Melvin Mittman, a big, beefy guy who played the accordion but spent most of his time at the gym, said he liked to use the bums’ bodies as punching bags to see how hard he could hit. Koslow and Mittman were from good Jewish families, but both of them—incredibly—sported sad, teenage Hitler mustaches.

Koslow, the more disturbed of the two, had been trouble since second grade, when he had leapt up in class, pointed to his teacher, and yelled, “Let’s get her!” By the time he was twelve, he had taught himself German so he could read and reread Mein Kampf.

With one of their accused gang members turning state’s evidence, Koslow and Mittman were found guilty of torturing a vagrant by burning the bottoms of his feet, marching him seven blocks to the water’s edge, and then drowning him in the East River. Koslow had told a court-appointed psychiatrist—none other than Dr. Fredric Wertham from Nuremberg, the anti–comic book crusader—that he read violent comic books like Nights of Horror, a cheap black-and-white booklet on sale in Times Square—and printed in Eugene Maletta’s Queens basement.

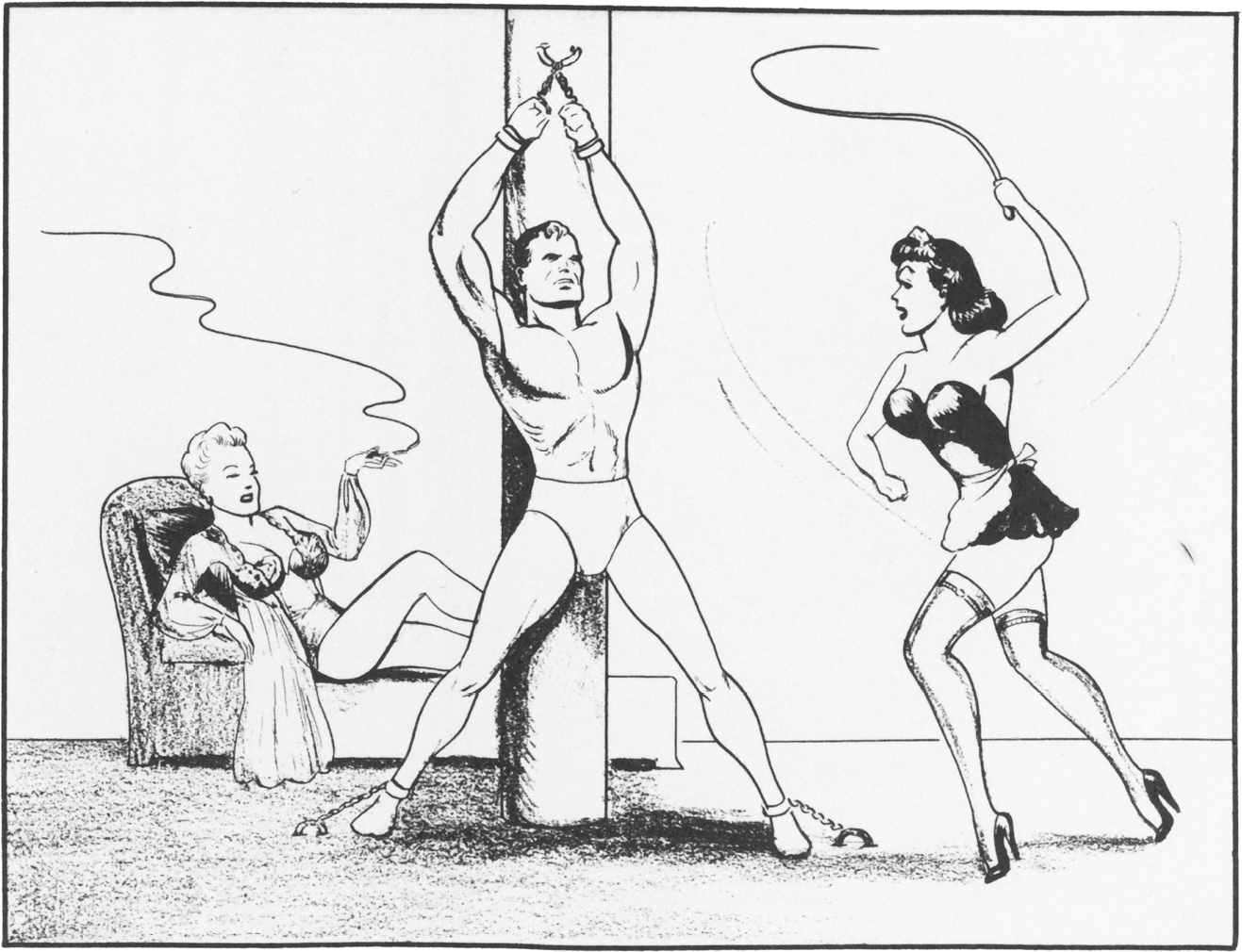

The things Koslow had done—whipping young women and making his homeless victims kiss his feet—were activities laid out in the illustrated pages of Nights of Horror. An S&M fetish comic that made Harry’s sex pulps look like fine art, Nights of Horror featured women and men dressed in black leather being tortured. Koslow had told Wertham that he had worn his black leather pants on the night of one of his rampages and that the black whip they had used to lash the girls in Williamsburg’s McCarren Park was purchased for $2.69 from an ad in a comic book.

Koslow’s confession led to the police raiding Eugene Maletta’s Queens shop on September 15, eventually leading them to a larger pornography ring that sold magazines and books out of Times Square. Maletta’s copublisher, a guy named Clancy who wrote the Nights of Horror “story lines,” escaped prosecution, tossing his remaining scripts and artwork into Long Island Sound.

“ESTELLE, BY SIGN, INDICATED THAT SHE WISHED TO HAVE THE MAID CONTINUE.”

The terrible twist to the Thrill-Kill story was that a neighbor of Clancy’s had drawn the horror comics. That neighbor was Joe Shuster—Jerry Siegel’s partner and co-creator of Superman.

To make a living, Joe had done anonymous drawings for all sixteen issues of Nights of Horror. His characters looked just like Lois Lane, Clark Kent, Lex Luthor, and Jimmy Olsen, but in leather and brandishing bats, paddles, and whips. The typewritten, crude quality of the comic harkened back to the primitive DIY Science Fiction magazine that Joe and Jerry had published in high school back in Cleveland. Except the characters were whipping and torturing one another.

One story was titled “The Bride Wore Leather.” Another, called “Slave Camp,” starred the devil himself and involved a cruel female Nazi guard with a whip. Characters were named Clark, Jerry, and Joe. It’s not clear if Joe was just desperate for cash or if he wanted to mess with Harry and Jack Liebowitz. Here in simple pen-and-ink line drawings were DC Comics’ beloved characters, doing things that would make Harry’s smoosh characters blush. Nights of Horror #17, which Maletta retitled Hollywood Detective in the chaos of the Thrill-Kill murders, featured a blond up-and-coming movie star named Nora (Norma!), who looked a lot like Marilyn Monroe, being tortured and stripped nearly naked, then tied up and placed inside an iron maiden.

When Harry first saw the characters in Nights of Horror, he no doubt recognized their faces and Joe’s telltale style, with its simple, but clean, bold lines. The old pornographer in him probably laughed out loud and shouted, “That son of a bitch!” His and Jack’s vengeance on Joe and Jerry had been turned around to bite them right in the ass. Artists both retired and in the current stable at DC Comics likely recognized Joe’s style as well, but mum was the word. The connection between Superman and Nights of Horror would come to light nearly a half century later when comics expert Gerard Jones would write about it. (Jones himself would eventually be convicted of possession of child pornography.)

Jack and Harry and the rest of the comics industry went into immediate damage control mode. The day after the Queens raid, they and their fellow comic book publishers held a press conference at the Waldorf, announcing a new-and-improved comics code and appointing their own comics czar, New York judge Charles Murphy, a former adviser to Mayor LaGuardia, to help rid the industry of obscenity and lurid images. They would also create a seal of approval promising that their contents were safe for young minds. Stores, under pressure from parents and priests, wouldn’t carry comics without the seal.

When the Thrill-Kill story hit the press, Joe must have been terrified, worried he would be implicated in the case. Thrilled though he may have been that Harry and Jack and the rest of the legit comics industry were squirming, he surely never dreamed his art would cause anyone actual physical harm. Perhaps he encouraged Clancy to throw all the artwork in the Sound.

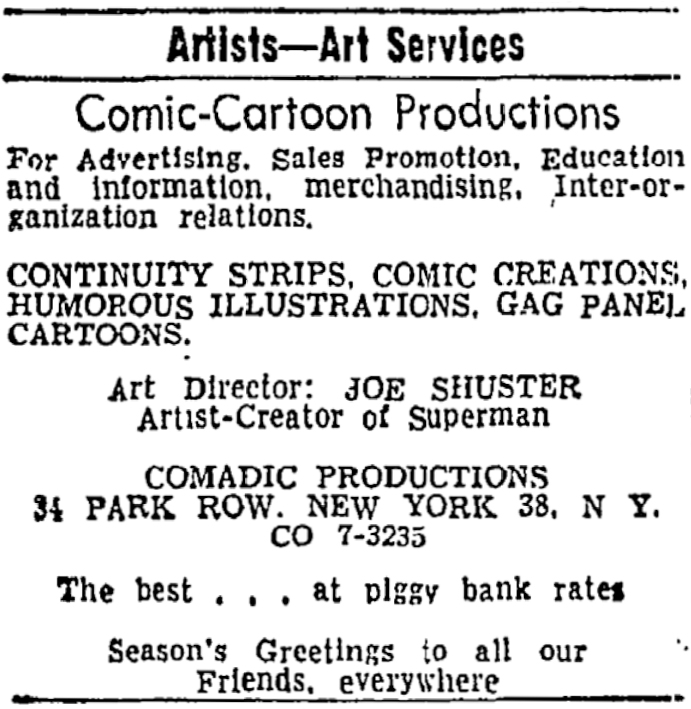

While the Thrill-Kill trial was still underway in late autumn, Joe ran a heartbreaking ad in the New York Times for new work in an attempt to move away from the horror comics:

The Thrill-Kill case was tossed like kindling on the fire of the comic book burnings that had been scattered across the country. In February of 1955, the New York State Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication of Comics, with Dr. Wertham’s help, laid out a point-by-point comparison of Nights of Horror and the crimes committed by the Thrill-Kill Gang. “The worst thing about the comic books,” said Dr. Wertham, “is that they give complete courses in crime. I’ll show you how these Brooklyn boys got their start.”

Many publishers and distributors self-censored, folding their horror comics on their own. Bill Gaines, the son of Max, the publisher who had been the link between Harry and Jerry back in the 1930s, helping get Superman off the ground, had reengineered his father’s business, and become one of the pioneers of the horror comics. Publishing titles like Tales from the Crypt, Gaines had a monthly circulation of 2.6 million before the Thrill-Kill hysteria. He now watched his sales drop off by a third. Due to protests from parents and religious groups, newsstands refused to carry his horror comics. The week of the Queens raid, Gaines announced he would stop publishing all of them—and instead focused on his MAD comic book, which he would change to a larger magazine format, partly to avoid the new comics code.

Though he surrendered to censorship, Gaines was nowhere near convinced the horror comics were tied to juvenile delinquency and said his new business strategy would have a whole other group angry at him—his college-age readers. “I don’t think anyone was ever harmed by anything they read,” said Gaines in the days leading up to the Thrill-Kill trial. “Neuroses are caused by real emotional experiences. Anyone who has studied psychiatry knows horror stories provide a harmless outlet for the hates that are normal to children. They can hate a figure on paper.” But, he said, it was “suicidal to buck this kind of censorship.” If he didn’t appease the parents, they might drive him out of business altogether.

By 1956, Gaines and the rest of the industry had taken a major hit, with 650 comic book titles whittled down to 250 and hundreds of comics artists laid off. The Nights of Horror ban was eventually brought before the Supreme Court, which voted 5–4 in 1957 in favor of censorship. FDR’s old Jewish friend and appointee Justice Felix Frankfurter, who had refused to believe news of the Nazi death camps, wrote the majority opinion, calling the magazine “dirt for dirt’s sake.”

Harry’s luck was running out.