Chapter 2

Origins

Concentration camps existed a generation before the Third Reich proclaimed its existence, even though they might not have looked like Dachau. Where do the origins of the camps lie? Traditionally, the answer is South Africa, and one observes the same kind of peculiar British pride in being the originators of concentration camps as one sometimes encounters when discussing the occurrence of ‘total’ genocide in the British settler colony of Tasmania. Yet historically speaking, it is too simple to say that the British simply ‘invented’ concentration camps in the context of the Anglo-Boer War. First, there were precedents in Cuba and in the Philippines; but more to the point, the phenomenon of the concentration camp as it appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the logical extension of phenomena that had long characterized colonial rule: the use of reservations, of deporting population groups from their original places of residence to unsuitable locations away from the developing settler-colonial territory, and of island prisons designed to hold unwanted remnants of indigenous peoples. Quarantine and lazaret islands, such as those in Mahon harbour, leper colonies, workhouses, slavery plantations, and asylums might also be regarded as earlier precedents, if only insofar as they show that the principle of isolating groups perceived as dangerous has a long history.

The Cuban and South African camps were certainly called ‘concentration camps’ but we need to bear in mind that the term has, since the end of the Second World War, called to mind something different from what it originally meant. That fact means that the early camps have been exploited by particular national myth-makers, who derive satisfaction from playing on the implied suggestion that ‘concentration camps’ in South Africa or Cuba share similarities with those built by the Nazis. This means we need to analyse what the first concentration camps were for, how they developed, and, most crucially, how they differ from those that came later. It is important, as Iain Smith and Andreas Stucki, two historians of concentration camps in colonial settings, remind us, ‘to acknowledge distinctions when the same term is used to describe widely differing phenomena in different contexts and eras’. That does not mean that there are no links to be found between camps in one place or time and another, merely that one cannot take such links for granted. Most important, the term ‘concentration camp’, like any other concept, means different things over time. Yet studying the early concentration camps can help us to understand how and why the camps emerged when they did and clarify the links and differences between them and the concentration camps of the fascist and communist regimes of the mid-20th century.

Prior to the existence of ‘concentration camps’, we can see that places of exclusion that colonial authorities set up often look, from today’s perspective, like proto-concentration camps. That should not be surprising, since an institution such as a concentration camp bears similarities to many other sorts of institutions, such as military encampments, workhouses, reservations for ‘natives’, POW camps, and so on. Examples are easy to find. In the United States, the 1830 Indian Removal Act authorized the deportation of indigenous people from east of the Mississippi River to the as yet non-incorporated territories of the North American continent. The so-called ‘Five Civilized Tribes’—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek nations—were deported, on what became known as the ‘Trail of Tears’, to a territory in present-day Oklahoma. The deportation itself was catastrophic for the Indians, thousands of whom died en route. But the worst would happen on arrival: of the 10,000 Creeks who were ‘resettled’, for example, some 3,500 died of ‘bilious fevers’. The site was not a ‘concentration camp’ in the sense of being a guarded site of confinement; but the idea—and the reality—of dumping a ‘superfluous’ population group in a place where they had no connection with the land, where there were few natural resources, and where they would receive no aid from the American authorities forms part of the background to the history of the concentration camps. Other examples in the American context include the fate of the Diné (Navajo), who in 1864 were forcibly walked 300 miles from Fort Defiance, Arizona, to Bosque Redondo in New Mexico, where they were interned for four years, living in covered holes in the ground; or the Chiricahua and other western Apache peoples who were held in reservations in the 1870s and 1880s, in a disastrous policy which led to years of hardship and warfare.

In the same year as the Indian Removal Act (1830), the remaining Australian Aborigines on the island of Tasmania, who had been hunted down and killed since the start of European settlement fifty years earlier, were forcibly removed to Flinders Island. By 1838, of the 200 Aborigines sent there, only eighty remained alive. This form of segregation is not the same as holding civilians in a concentration camp, but the similarities are undeniable. Although conceived by the British rulers of Tasmania as a ‘civilizing’ effort, and even if the Aborigines were persuaded of the necessity of moving to Flinders Island—the alternative was to be shot on sight by settlers—the island had few resources suitable to sustain the Aborigines’ lives. Although not a form of outright murder, the expulsion to Flinders Island was effectively a form of slow death and the island itself a sort of open-air camp.

Although we can see institutions which suggest that states were starting, especially in the colonial context, to ‘manage’ unwanted civilian populations by deporting and isolating them, the ‘concentration camp’ proper is usually understood as having originated in Cuba in the context of the Spanish–American War, in South Africa in the context of the Anglo-Boer War, and in the Philippines in the context of American intervention there. In each of these cases, professional European armies, which considered themselves to be fighting primitive, unworthy opponents, carried out a scorched earth policy in order to clear a rural population suspected of supporting guerrillas; this practice led to the creation of camps designed to hold this uprooted population. In the colonies, where it was easy for armies focused on means and not ends to abandon the rules of war newly set down in the 1899 Hague Laws (although these did not apply to civilians), the turn to using camps happened quickly and easily.

In Cuba, following the rebel attack on the island’s sugar plantations, led by Maximo Gomez, thousands of rural workers and their families were left destitute. The rebels demanded that they should move to areas under their control but the Spanish, in response, destroyed the rural workers’ crops and livestock and insisted that the population should be ‘re-concentrated’ in areas it controlled. During the period 1896–7, the Spanish general Valeriano Weyler was responsible for moving half a million people, over a quarter of the island’s population, to concentration centres, where more than 10,000 are believed to have died of starvation and disease. Although the re-concentration policy was ended in 1897, when Weyler was recalled, the majority of those held in the camps had nowhere else to go and large numbers continued to die throughout 1898.

In the Philippines, war between the Americans and the Filipinos erupted in February 1899 following the American defeat of the Spanish in 1898, as rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo’s forces demanded independence and the US opted for annexation. Defeated in formal battle, the Filipinos turned to guerrilla warfare. Under General Arthur MacArthur, in 1901–2 the Americans pursued a policy exactly along the lines they had so heavily criticized the Spanish for in Cuba: destroying dwellings and crops on south-west Luzon, ordering the killing or capturing of men found outside the towns, and forcing rural civilians into ‘protected zones’ in Batangas and Laguna provinces. More than 300,000 were held this way, of whom at least 10,000 died of disease.

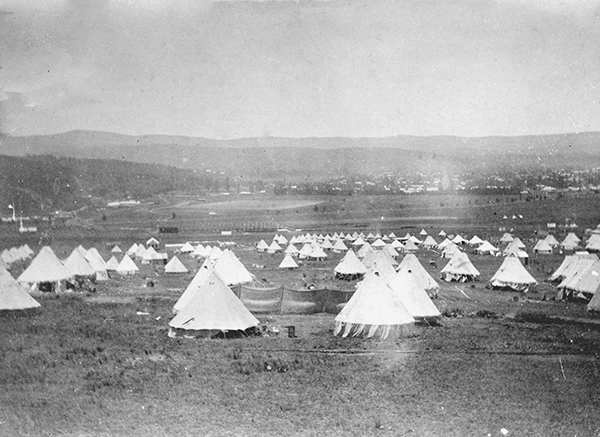

If concentration camps first appeared in Cuba or in the Philippines, it is the camps established by the British army in South Africa that are most people’s first point of reference, especially in the English-speaking world. British welfare campaigner Emily Hobhouse’s condemnation of the camps as a terrible deviation from civilized human behaviour, especially her condemnation of what she called ‘child murder’, are widely recalled as the first recorded indictments of the evils of concentration camps. The camps—first called ‘refugee camps’ or ‘burgher camps’ and only ‘concentration camps’ after 1901—were set up in August 1900 and were intended to gather Boer civilians whose land and farms had been destroyed by the British army’s scorched earth policy. That policy itself was the result of the ostensibly defeated Boers turning to guerrilla warfare rather than conventional battles; the camps were supposed to deprive the Boers of support and resources such as food, ammunition, and intelligence. As the number of camp inmates rose over 100,000, the British army soon found itself unable to meet the needs of so many people, with disastrous consequences (see Figure 1). But the people who found themselves in British concentration camps were not only white, as Afrikaner collective memory recalls. In fact, almost as many black Africans as Afrikaners died in the camps, even though Afrikaners appropriated the camps for their own political gain after the Anglo-Boer War. The black Africans were likely to find themselves used as a labour force, however, whereas the Afrikaners were also subjected to social engineering measures such as schooling for children conducted in English.

1. Norvals Pont camp in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War.

Nor were camps’ inhabitants solely middle class, again as Afrikaner collective memory holds. The first camps, like that at Bloemfontein, housed destitute refugees, but as historian Elizabeth Van Heyningen says, ‘by the end of 1900, and as the commandos gained strength and the British military became increasingly frustrated, the camps began to acquire a punitive function’. This sort of poor relief in the context of colonial war meant that helping the ‘indigent Boer’ permitted the creation of camps which soon became more forms of incarceration than assistance. Indeed, the scandalously high death rates in the camps’ early months indicates a total disregard for civilian life on the part of the British army. But from the colonial authorities’ point of view, especially the military, in South Africa just as in Cuba or the Philippines, such detention of civilians was justified in terms of ‘clearing’ the countryside of potential support for ‘an evasive enemy who had resorted to guerrilla warfare’. Concentration camps held civilians but were considered an arm of military strategy, even if ‘humanitarian’ claims could also be made that such camps permitted civilians affected by the war to be safely housed and fed (see Box 1).

Box 1 Concentration camps in the Anglo-Boer War

The camps established by H. H. Kitchener were designed to flush out guerrillas by clearing the countryside. Their poor organization led to the deaths of some 45,000 people, about 25,000 Boers and 20,000 Africans, facts that were condemned by Emily Hobhouse among others and which have long been regarded as a stain on the British Empire. Recent research by historians such as Iain Smith and Elizabeth Van Heyningen shows that once the British proconsul Alfred Milner took charge and placed the camps under civilian control, conditions improved, that there was considerable regional variation in the camps’ death rates, and that the memory of the camps has been exploited by Afrikaner nationalists. All of this more nuanced history is right and proper but it is worth bearing in mind Jonathan Hyslop’s reminder that the camps’ early period was disastrous. He adds:

Of course no one should sensibly suggest that there was a moral equivalence between these institutions and the Nazi or Stalinist camps. But … the international 1896–1907 developments did mark an unprecedented level of the military organization of civilian populations. The South African camps therefore represent a form of instrumental rationality which is not without affinities to later, more totalitarian events. Indeed, the South African camps’ sanitary and modernizing elements may in a sense have made them all the more pernicious, by legitimizing the camp idea internationally. It seems to me that the danger in the new literature is that in its anxiety to debunk Afrikaner nationalist ideology, it inadvertently takes on a curiously apologetic tone on behalf of the British military and administrative machines.

(‘The Invention of the Concentration Camp’, p. 260 n. 33)

As Elizabeth Van Heyningen notes, it is unhelpful that

The term ‘concentration camp’ has acquired far more terrible connotations since the Second World War and, for some people, the distinction between the South African and Nazi camps has blurred, contributing to a belief that the British camps were genocidal.

Still, as she goes on, ‘no one chooses to be a refugee and the term always implies deprivation and suffering. The polemics of war are unhelpful in understanding the history of the camps.’

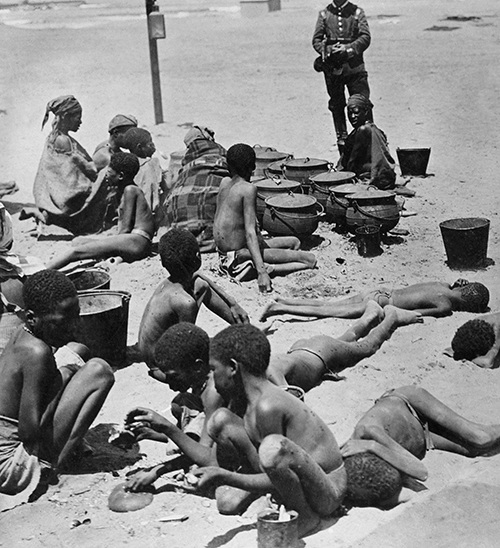

The other colonial context in which concentration camps appeared was German South-West Africa (today Namibia). In the context of the Herero and Nama War (1904–7) what is today widely regarded as the first genocide of the 20th century took place, with some 65,000 of the 80,000-strong Herero population murdered or driven into the desert to die of thirst. At the end of the war against the Herero, the German colonial force established what it called Konzentrationslager or Gefangenenkraale for the surviving Herero, brutal camps in which the death rate was 45 per cent, or twice as high as the British camps in South Africa (see Figure 2). Given that the term Konzentrationslager had been used in German, up to that point, to refer to the British camps in South Africa, it is clear that the British experience in their guerrilla war was regarded as some kind of guide by the Germans. Although similar to the Cuban and South African cases in that the German army regarded guerrilla warfare as intolerable, there was a crucial difference in that the South-West African camps were conceived as pacification and ‘punishment’ camps for an already defeated enemy who could henceforth be used for forced labour and not as a means of isolating civilians in the context of a guerrilla war. As a result, the harder attitudes already prevailing among the colonial rulers meant that from the start these camps endured a harsher rule.

2. Shark Island, German South-West Africa (Namibia).

The most notorious case was Shark Island (Haifischinsel), off the Namibian coast, to which 1,800 Herero were deported after the war. One eye-witness, a German missionary from Lüderitz Bay, noted that the Hereros’ mistreatment whilst at work, the lack of fresh food, and the raw sea climate quickly weakened them.

Even more than these evils, their isolation on the furthest corner of Shark Island contributed to the eradication of the people’s will to live. They became gradually apathetic towards their misery. They were separated from the outside world by three high barbed wire fences.

By the time the camp was transferred to the mainland in April 1907, on the orders of Ludwig von Estorff, the new head of the Schutztruppe (colonial army), only 245 Herero were still alive, of whom only twenty-five were able to work. These figures appear to justify historian Isabel Hull’s claim that the German army’s military culture—which required maintaining prestige in the face of ‘savages’, a quick and absolute victory, and a low level of priority to logistical questions—proved fatal for Germany’s colonial subjects once they took up arms against their ‘masters’.

The fact that the Herero were subjected to forced labour only hastened their demise, even if the decision to put them to work brought a slight increase in food rations. They were primarily forced to work building railway lines. Private firms also made use of the Herero as forced labourers, for example the shipping firm Woermann, as well as small local firms, who paid a fee to the camp administrators for each person they took. In general, however, the dispute between different German military leaders as to whether the Herero should be used for labour or should be left to die in the camps made no difference to their massive death rate. Although there were no death camps in German South-West Africa, the concentration camps there brought about an annihilation through neglect and thus they contributed enormously to the German reshaping of South-West African society.

These colonial camps were ‘concentration camps’, then, because that is what those who established them called them. Yet they were not uniform and, in the case of Cuba at least, it is questionable whether the term ‘concentration camp’ really applies, given its later 20th-century connotations. Why did they emerge at this point, and what contributed to their steady radicalization? The first thing to note is the professionalization of European armies in the late 19th century. This professionalization paradoxically permitted intensified violence against civilians because, as historian Jonathan Hyslop argues, it led armies to regard other armies as worthy of respect and subject to rules when taken prisoner, but permitted the development of ‘a doctrine of military necessity as justifying extreme violence’ when dealing with civilians or those figured as ‘irregular troops’. Concentration camps emerged as weapons of war and became tools of total war even though, paradoxically, they were used to incarcerate not enemy combatants but supposedly seditious civilians. Particularly in the colonies, where racial assumptions of native inferiority and European superiority were taken for granted, any threat to this way of thinking was intolerable. Second, the spread of new technologies of communication at the turn of the 20th century facilitated the easy spread of information with respect to all aspects of life, including military and carceral techniques. Third, and of greater importance for understanding the radicalization of concentration camps, the brutal experience of the First World War, the creation of nationalizing states in the aftermath of the demise of the old European empires, a development that occurred at the same time as the European overseas empires were also at their zenith, gave states a major spur to conceive of widespread incarceration of civilians in terms of their own security or ‘self-defence’.

Particularly during the Great War, notions of states’ ‘self-defence’ received a boost through the holding of large numbers of POWs and the internment of ‘enemy’ civilians, procedures which set important precedents for the new nation states. The whole of France was legally placed in a state of siege by President Poincaré in August 1914, a condition which remained in effect until 12 October 1919, and during which time the National Assembly became nothing more than a mouthpiece for rule by decree. Where states of exception formerly existed in colonial spaces, now they were being created in Europe; they were enablers of mass incarceration.

Between 1914 and 1918 between eight and nine million soldiers were held as POWs, about one in every nine men in uniform. The camps in which they were held were not concentration camps—not because they were too pleasant or comfortable but because they held soldiers and should thus be classed as POW camps. Their significance here is that they indicated a newfound ability to transport and maintain ever larger numbers of people on the part of modern states. Or more accurately, they indicate that states lacked or chose to restrict the ability to maintain large numbers of people. Over 9 per cent of the 2.11 million Habsburg POWs in Russian captivity died in the camps, and another 9 per cent were missing. Nearly 10 per cent of the 158,000 German soldiers in Russian captivity died; more than 72,000 of the 1.4 million Russian POWs held by the Central Powers died according to contemporary German estimates—the true figure is likely to be higher; nearly 20 per cent of Italian POWs (over 92,000 of 468,000) died in Austrian captivity.

These figures reflect the simple fact that food was withheld from POWs, that they were often forced to work in areas where they came under fire—contrary to the 1907 Hague Convention—and that they received inadequate clothing and shelter. One British soldier held in Sennelager camp in September 1914 described it as ‘an open field enclosed with wire … there were no tents or covering in it of any kind. There were about 2,000 prisoners in it—all British. We lay on the ground with only one blanket for three men.’ Italian POWs were marched to camps whose names—Mauthausen, Theresienstadt—immediately indicate the link between POW camps and later concentration camps. One Italian POW wrote home: ‘We are treated like animals; with our tattered shoes we resemble tramps. I hope this damned war is over soon, or else we will die in Austria.’ Yet none fared worse in Austrian captivity than the Serbs who, according to the Italian high command, were kept caged like animals and fed scraps, leading them to conclude that ‘Austria intends to destroy the [Serb] race.’ As historian of the POW camps Heather Jones notes, in the First World War the

prisoner of war camp began the conflict as a means of ensuring that the captured enemy combatant was kept away from rejoining the battlefield fight; in other words, with a purely military function; it ended the war as a sophisticated system of state control and as a laboratory for new ways of managing mass confinement, forced labour and new forms of state-military collaboration.

Even more significant for later developments was the internment of civilians during the First World War, and not only in Europe. In 1915, in a move that had enormous ramifications for the rest of the 20th century and beyond, France revoked the status of naturalized citizens from people of ‘enemy origin’. Belgium, Italy, Austria, and Germany soon followed suit, with the result that the idea became widely accepted that one could be stripped of one’s nationality and reduced to statelessness and thus deprived of the benefit of law—this being long before the UN Refugee Convention, of course. British civilians in Germany, for example, were held in the Engländerlager Ruhleben near Berlin. In total, by the end of the war, some 111,879 ‘enemy civilians’ were in German internment. 24,255 German, Austrian, and Hungarian civilians were still interned in Britain at the same point, October 1918. The Austro-Hungarians deported French and Belgian citizens for forced labour and Italian citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire for being ‘out of place’: they were either interned or deported to Italy. From 20 May 1915 they were held in what were called ‘concentration camps’, one of which, at Steinklamm, the Italians referred to as the ‘Campo della morte’ (camp of death). The internees were treated very harshly, forced to work for little pay, and received inadequate food supplies. The Italian royal commission of investigation noted, in fact, that the ‘really tragic characteristic of these concentration camps was the hunger’ and, in the face of large numbers of deaths, especially of children, claimed that the Austrians intended to ‘destroy or reduce to a small number the Italian race on its territories’. The Austrians also rounded up some 7,000 so-called ‘Russophiles’ in eastern Galicia and Bukovina and deported them to the Thalerhof camp near Graz, where nearly 1,500 died. In the colonies, German priests and civilians in Togo and Cameroon were rounded up and interned first in Dahomey and later in Algeria and Morocco, and in British East Africa German civilians were deported to camps in India. Whether undertaken out of fear of ‘fifth columnists’, as reprisal actions, or in order to obtain forced labourers, the scale of civilian internment during the war was far greater than anything that had been witnessed before.

Most notable, however, were the huge numbers of refugees created by the Russian Revolution of 1917 (about 1.5 million), by the Ottoman attacks on Armenians (about one million), as well by the collapse of the European empires at the end of the war, which affected among others Greeks, Turks, and Bulgarians. Within the Russian Empire itself, before the Bolshevik Revolution the Tsarist regime deported some 300,000 Lithuanians, 250,000 Latvians, 200,000 Germans, 500,000 Jews, and 743,000 Poles from the western border regions. As a group of Russian Germans claimed: ‘We didn’t want to move, we were chased away … we were forced to burn our homes and crops, we weren’t allowed to take our cattle with us, we weren’t even allowed to return to our homes to get some money.’ By mid-1916, in Russia’s larger cities refugees made up more than 10 per cent of the population; in Kharkov it was 25 per cent and in Samara 30 per cent. There were philanthropic efforts to help them, but these were insufficient to counter the power of a nationalist language of ‘floods’, ‘swarms’, ‘deluges’, and other biblical disasters, which quickly became associated with refugees. The Times, for example, described Belgian refugees in Britain as ‘a peaceful invasion’, and Russian commentators used even more colourful terms such as ‘lava’ or ‘avalanche’. These population movements saw emergency accommodation being created in schools, factories, barracks, monasteries, and so on, and the creation of refugee camps for the first time on European soil. The refugees were not always grateful, however. Belgians in Britain, for example, were constrained by the Aliens Restriction Act (4 August 1914), confining them to specific parts of the country; they complained that this amounted to being held in a ‘concentration camp’.

These developments together—the war itself, the large numbers of civilians and combatants being held in camps, the existence of huge groups of refugees, and the creation of states of exception in European polities—contributed to a rapidly changing political environment, one in which whole groups could fall under suspicion and find themselves subject to states’ paranoias and fears, which mushroomed at this time. Klaus Mühlhahn claims that

The temporary internment of displaced and dislocated groups and POWs in the wake of the war together with the politicisation of citizenship and nationality and the temporary suspension of regular legal procedures provided the conditio sine qua non that facilitated the emergence of concentration camps on the European continent.

This might be somewhat overstating the case—other conditions were also relevant, not least the colonial precedents—but his claim is a useful rejoinder to those who only remember the South African camps and forget that within Europe itself camps for civilians existed several decades before the Nazis came to power. The First World War generated the interventionist state, threatened the rule of law, intensified notions of national belonging, and raised fears about civilians and citizens who were ‘out of place’—all of which resulted in the creation of camps. Twenty years later, and despite the Geneva Convention of 1929, the same phenomenon would reappear as ‘enemy aliens’—including German and Austrian Jewish refugees—were interned on the Isle of Man in the UK, as camps opened in the south of France for refugees from the Spanish Civil War, and as similar sites appeared around the world. Camps for the stateless, the non-naturalized, and simply those rendered suspect by the dominance of nationalist ways of thinking had become normalized.

These European developments indicate a link between colonial rule and the radicalization of state actions in Europe. But perhaps the most radical indication of the way in which concentration camps were changing during the period of the Great War is to be found in the Ottoman Empire, where some historians talk of concentration camps being used in the genocide of the Ottoman Armenians. In this context, one can clearly see the ways in which ‘concentration camps’ could rapidly drift into something altogether more terrible in the context of total war. These camps were often holding pens during the process of deportation of Armenians from the Turkish interior to the deserts of Syria. At Aleppo, for example, large numbers of deportees were forced to camp along the railway tracks outside of the city so as not to overcrowd the city itself. ‘As a result,’ Hilmar Kaiser writes, ‘new concentration camps emerged for deportees in transit.’ One of them was Katma (or Ghatma). One witness, Vahram Daderian, described it thus in September 1915:

The sea of people with coaches, horses, donkeys, mules and people are filled in all direction [sic]. The atmosphere is filled with a deafening sound of cursing, crying, and sighing. Skeleton arms are stretched out everywhere, asking for a piece of bread … There is a terrible stink that tears everyone’s nose. Everywhere is covered with unburned, rotten human waste, corpses etc. Besides that, ten thousand people have left their filth, and have contaminated the whole area, and it is not possible not to choke. Holding our nose and covering our eyes, we proceeded among these corpses and garbage, and after a while we stopped at a place at the end of the tent city, which was specially prepared for us.

(cited in Kaiser, At the Crossroads, p. 19)

Or, as Elise Hagobian Taft put it in her memoir Rebirth (1981), describing Katma in December 1915:

The sight before me was horrible beyond description. Hundreds and hundreds of swollen bodies lay in the mud and puddles of rain water, some half-buried, others floating eerily in rancid pools, together with rotted bodies and heaps of human refuse accumulated during the week-long rain. Some victims—only the upper torsos emerging from the mud and puddles—were breathing their last. The stench rose to the heavens. It was nauseating beyond belief. The scene was like a huge cesspool laid bare and made to stink even more under a hot sun.

(cited in Kaiser, At the Crossroads, p. 21)

Or finally, in Naomie Ouzounian’s description, written in 1982:

The ‘camp’ where hundreds of thousands had already been thrown together was a narrow strip of the desert, surrounded by bare hills. The hot, humid air was filled with the stench of human refuse and decaying unburied bodies. I couldn’t breathe, oh, if only I could take a deep breath! The name of this hell was Ghatma. ‘Dear Lord, I hope there is no Ghatma in the hereafter, and if there is one, forgive my sins and do not condemn me to it’, I prayed.

(cited in Kaiser, At the Crossroads, pp. 21–2)

Kaiser goes on to talk of the ‘world of the death camps’ as the genocide became more coordinated and ferocious in 1916. Other historians agree, Ron Suny claiming that the ‘concentration camps’ at Tel-Abiad, Ras al Ayn, Mamureh, Katma, and Aleppo ‘were way stations toward extermination. They were death camps.’ Taner Akçam too says of the ‘concentration camps’ of Aleppo that ‘the appalling sanitary and humanitarian conditions turned these into death camps’. Is this a metaphor? Ouzounian talks of the ‘camp’ at Katma in inverted commas, suggesting it was not really a camp in the sense of our working definition so much as a forced encampment where the deportees were left to fend for themselves. The language of ‘death camps’ here derives from the Nazi period, as does Suny’s claim that the name of Der el Zor ‘reverberates today with the final solution of the Armenian question’; the tragedy of the Armenian genocide is by no means diminished if we suggest that the term is not wholly appropriate. What we see in the Armenian genocide is something part way between the colonial dumping grounds and the Nazi death camps. People were not murdered on arrival at Der el Zor as at Treblinka; but they were separated off from the rest of the population and abandoned to die. The difference pertains solely to the institutional history of the concentration camp, the different logics of the perpetrators’ world views, and the means of technology at their disposal, not to the value of the lives of the victims in either case.

Over time, as we have seen in this chapter, concentration camps emerged not only as institutions developed by different states—which suggests that they tell us something about modern nation-state building—but as sites whose creators were radicalizing them in a logical fashion as the first half of the 20th century became increasingly violent. European racism, military culture, more rapid forms of communication, and increasingly available print media all contributed to the global diffusion of the idea of the concentration camp. Russian military officials, for example, first used the term konsentratsionnyi lager during the Anglo-Boer War and the Bolsheviks quickly revived the term after the 1917 revolution. In Germany, the term Konzentrationslager was first adopted from the British camps in South Africa as the designation for the camps set up to hold the Herero in German South-West Africa. After the war, in 1921, the term was again officially used to designate two camps, in Cottbus-Sielow and Stargard in Pomerania, established on the sites of former POW camps in order to hold ‘unwanted foreigners’, primarily ‘Ostjuden’, that is Jews from Eastern Europe. In Asia, the Japanese established their first concentration camp, Zhong Ma prison camp, in the village of Beiyinhe, about 100 km south of Harbin. The numbers of Chinese and Korean ‘bandits’ held there was small—about 500—but the significance of Zhong Ma was that the inmates were used as human guinea pigs in germ warfare experiments. It was thus the forerunner of the Japanese Special Unit 731, which between 1937 and 1945 carried out experiments on human beings at its facility in Ping Fan, near Harbin, as well as at sites in Nanjing and Changchun. Many other ‘corrective labour camps’, as the Japanese called them, were established across Manchuria in the 1930s.

The Chinese too, under the Nationalist Government (1938–49), set up concentration camps for political enemies, assisted in the process by the Germans and the Americans. Among them was General Alexander von Falkenhausen, a friend of Lothar von Trotha, the man responsible for suppressing the Herero in German South-West Africa, who advised the Chinese on the basis of German and British experience in the colonies, as well as his own role in putting down the Boxer uprising. The Guomindang was also advised by American officers. Stationed near the Chongqing prison camp, they helped to train nationalist Chinese agents in interrogation techniques. Although the European model of camps acquired a certain ‘Confucian’ twist in its Chinese variant—through the names of buildings, the designation of inmates as ‘people in self-cultivation’, and through the language of ‘thought reform’, for example—it is clear that the Chinese camp system also owed something to precedents in the European colonies and in Europe itself. In the interwar years, then, we see that concentration camps across the world appeared principally as an aspect of the development of modern states but also, to a more limited extent, on the basis of transnational exchanges of information and technology. As Dai Li, head of the Juntong or intelligence service, put it in a 1966 recollection: ‘It is correct, we had concentration camps; but I think that in times of war every state has organized similar institutions, detaining political prisoners as well as enemies and spies who do harm to national security.’

In the global context of colonial settlement and warfare, the rise of mass politics in Europe, the challenges to European empires, and the emergence of new, homogenizing nation states in the aftermath of the Great War—itself an occasion for radical approaches to internment of civilians and combatants alike—concentration camps became firmly established as part of the state’s carceral repertoire. According to Hyslop, the colonial camps, in comparison with what came later, ‘were very limited affairs in terms of the levels of guarding, violence and discipline to which the prisoners were subjected’. Nor were they entirely isolated from legal and civilian criticisms: Kitchener’s plans to expand his remit were blocked by the Cabinet, and in Germany von Trotha’s ‘war of annihilation’ created considerable scandal in parliament and in the press. Nevertheless, the idea of the concentration camp as a holding pen for superfluous or undesirable people who could be excluded from the realm of domestic and international law had, by the end of the First World War, become accepted as a technique of rule. The adoption of concentration camps by the Japanese in Manchuria and the Chinese nationalists in their attempt to put down communism makes the point clearly. But nowhere would this be more evident than in the Soviet Union, in Nazi Germany, and, after 1939, in Nazi-occupied Europe. It is to these two regimes, Nazi and Soviet, and the extraordinary world of camps they produced that we will turn next.