Chapter 6

‘An Auschwitz every three months’: society as camp?

Camps as warning?

In 2015, newspapers were reporting that part of the former concentration camp of Dachau (the ‘herb garden’—not part of the memorial museum) was being used to house refugees. The people whose refugee camp is one of the world’s most notorious former concentration camps are among the lucky ones. Other refugee camps in countries bordering Syria and in cities across Europe are holding ‘migrants’—as the press likes to call them—whose future prospects look much less promising. One might argue that the ‘refugee crisis’ itself in its European context is a rhetorical construct; it certainly seems bizarre that whilst countries like Lebanon and Jordan have each taken in over 1 million Syrian refugees, European countries are apparently unable to cope with tens of thousands.

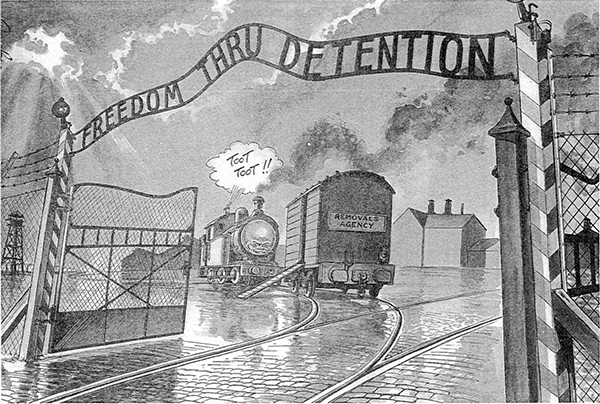

Are these refugee camps in Dachau or elsewhere concentration camps or even akin to them? The people forced to live in them clearly do not want to be there; the experience is humiliating. A 2009 Human Rights Watch report on refugee centres in Libya, whose construction Italy paid for, described ‘inhuman and degrading conditions’ inside them. At the same time as the refugees can expect a minimum of care, it is also quite clear to them that they are an unwanted population. The camps are there both to aid people who have had to flee their homes and to provide sites of their exclusion from the ‘world of nations’ (see Figure 9). Should we be alarmed that the 21st century is again going to become a century of camps?

9. ‘Freedom Thru Detention’, Dave Brown cartoon, Independent, 19 April 2000.

The matter is complex. There is no single type of concentration camp and no clear dividing line between a concentration camp and other sites of incarceration. If one searches book titles, one can find books that deal with the ‘South Korean Gulag’, the ‘Chilean Gulag’, the ‘Israeli Gulag’, the ‘Hungarian Gulag’, and many other supposed cases. The massive growth of California’s prison system is called by one analyst a ‘Golden Gulag’ because the ‘prison boom’ has seen a jump in incarceration rates of 450 per cent since 1980. This huge growth is partly a result of what some civil rights groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union refer to as the ‘school-to-prison-pipeline’, which refers to the ways in which poorer and more vulnerable children in the US are driven along a disciplinary trajectory heading for prison rather than education. There is even a book dealing with the ‘Gulag of the family courts’. Clearly the concentration camp image is good propaganda. We need to tread carefully. We also need to note, however, that some philosophers and sociologists have been quite outspoken with respect to the significance of concentration camps for understanding 21st century societies. It is a greater source of concern for today’s world to think about the growth and variety of camps than it is to prove that any one particular type of prison or camp system merits the term ‘gulag’.

For example, the idea that there are connections between historical concentration camps and contemporary sites or territories of incarceration receives scholarly backing from the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, who makes his claim by bringing together Michel Foucault’s concept of ‘biopower’ (the ability of the state to decide on the life and death of its citizens) and German legal philosopher (and Nazi) Carl Schmitt’s concept of the ‘state of exception’. Agamben argues that the camp has replaced the city as the biopolitical paradigm of the West. For Agamben the historian’s question as to whether camps originated in Cuba or South Africa is less important than understanding that camps have become ‘the most absolute conditio inhumana that has ever existed on earth’ and that rather than being a purely historical datum or an anomaly in human history, they are in some way ‘the hidden matrix and nomos of the political space in which we are still living’. Agamben defines the concentration camp thus: ‘The camp is the space that is opened when the state of exception begins to become the rule.’ Where the state of exception was once sparingly used to suspend the rule of law temporarily at a moment of emergency, the camp marks the point at which the state of exception ‘is now given a permanent spatial arrangement, which as such nevertheless remains outside the normal order’.

Agamben’s arguments have been very influential, with critics taking his definition as a starting point for examining all manner of institutions and developments in domestic and international law, not least the US’s suspension of the rule of law in holding people without charge in Guantánamo Bay. Agamben himself uses his theories to protest against biometrical data gathering, seeing it as a way for the state to extend its biopolitical reach, effectively making suspects out of citizens. Others have used the arguments about the spatialization and normalization of the concept of the state of exception to argue that the concentration camp is nowadays not an aberration but the norm. Whole swathes of territory, in this reading, might be considered ‘states of exception’, places where inhabitants have been abandoned by the rule of law and which are thus effectively concentration camps. What looks at first glance like a metaphor designed to awaken us to the cruel realities of many people’s lives might turn out to be a simple description of fact.

On the other hand, Agamben has been criticized for disregarding facts, making out of a vast panoply of camps—there was, as Nikolaus Wachsmann reminds us, no typical concentration camp in the Third Reich—an icon, ‘the camp’. This is not merely made to do service as an archetypal concentration camp, it supposedly tells us something about the inner life and logic of the modern state as such. Agamben makes the fact that the Nazis ruled according to Article 48 of the Weimar constitution—permitting rule by decree in exceptional circumstances—into a general rule of the modern world: that the ‘state of exception’ is increasingly becoming the norm, used as a means of suspending democratic politics (whilst formally retaining the liberal constitution) and controlling populations. One critic, the philosopher Ichiro Takayoshi, objects that Agamben’s attempt to find ‘the platonic form of the camp’ means that he transposes a legal concept—the state of exception, in which the exception, which is outside the norm, is included in the norm as a conceptual possibility—into the realm of the Nazi camps, where it does not apply. The inmates of the camps were not simultaneously inside and outside the law; rather, as Takayoshi says, they were simply designated as enemies, then ‘denationalized’ by having legal protection withdrawn, before finally being concentrated and/or eliminated in the camp system. The facts of the matter do not seem to support Agamben’s claim to have seen in camps of all sorts ‘the nomos of the modern’. Camps might indeed be embodiments of a state of exception because they represent a suspension of the law but it does not follow that the state of exception is the leitmotif of Western political culture.

Nevertheless, camps of all sorts do continue to exist today. Even if we do not subscribe to Agamben’s position, does anything unite refugee camps, IDP camps, migrant holding camps (such as Dachau’s herb garden, Mineo in Sicily, or Bela near Prague), makeshift refugee camps such as the former ‘Jungle’ in Calais or sport stadiums in Athens, or detention centres for asylum seekers such as Yarl’s Wood in Oxford or Colnbrook near Heathrow Airport? In considering this question, Agamben’s insight that camps—or rather, those held in them—represent the deployment of the ‘state of exception’ is helpful, for it assists us in thinking through what a concentration camp is, where the state of exception is explicit and intended, and what might better be thought of as places where people are held against their will but where the state of exception is not, or is only partially, enforced (if that metaphor of a ‘partial state of exception’ makes sense).

Agamben’s argument can also help with considering the question of how development intersects with the existence of camps. It is true that the number of people existing on less than $1.25 a day has halved in the last twenty-five years, from 1.9 billion to 836 million. Global poverty is something that people care about, although there is a paradox in rich countries offering even relatively large amounts in aid to countries whose poverty is structurally entrenched by the trade policies and consumption patterns of those same rich countries. Questions about the ethics of development aid are beyond the scope of this book, however. What interests me here is the question of whether there is anything to be learned about the contemporary world by asking this question: do the inhabitants of the ‘global south’ (what used to be called the Third World) live in a giant concentration camp?

This most capacious understanding of what constitutes a concentration camp is put forward by Vinay Lal, who claims that the global south’s inhabitants are effectively slave labourers producing cheap goods to satisfy the rich countries’ consumerist obsessions, the victims of an invisible genocide. Historically one can find evidence that lends some support to this view. As we have seen in examples from South Africa, Cuba, and the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century, and Kenya, Malaya, and Algeria after the Second World War, ‘destruction and “development”, the emptying of some areas and the stabilization, improved control over, and exploitation of others, were two sides of the same coin in anti-guerrilla warfare’, as Christian Gerlach writes. Schemes for ‘villagization’ or the control of the jungle in Malaya or Kenya were premised on stemming support for guerrillas and ‘modernizing’ the country. In Lal’s reading, the argument is taken further: ‘development’ is genocide and the people who service its institutions are dwellers in the world’s largest concentration camps. Ironically, in contrast to practitioners of ‘open genocide, who may have to face the gallows or the humiliation of trial before an international tribunal, the stalwarts of this form of ethnic cleansing are often feted for their humanitarian contributions to human welfare’.

Philosopher Alfonso Lingis makes an equally provocative argument when, in trying to shock readers into realizing the realities of life for people in what would today be called the ‘developing world’, he argues that the ‘forty thousand children dying each day in the fetid slums of Third World cities’ constitutes ‘an Auschwitz every three months’. The reference is made in passing in the context of a passage where Lingis argues that one has to ‘speak for the silenced’; it is not a cogent, worked-through comparison. Quite the contrary: it is Lingis’s anger which jolts the reader into considering whether the comparison can and should be made at all.

Lal’s and Lingis’s positions are nothing if not thought-provoking. But is it really the case that the global south exists in a state of exception? Structural and institutionalized poverty, ossified through clientelist relations of dependence on Western capital, creates a harsh reality, but the camp terminology—being abandoned by the law or excluded from the ethical universe—does not do justice to the complexities of the relationships that characterize the ‘world system’. There are, for example, lawyers, NGOs, and politicians able and willing to represent the inhabitants of the global south, just as they are able to mobilize and represent themselves. As a metaphor for a life that is restricted, without limited hope for improvement, and a feeling of being trapped in a position of dependence and reliance on unseen ‘masters’, the idea of the global south as camp contains echoes of the colonial past that give us cause for concern. But perhaps Agamben’s argument is more useful when we turn to the variety of camps—in the stricter sense of enclosed sites holding people who do not wish to be there—that exist in the world today. Are concentration camps a warning for our world? In order to address this question we need to consider what camps mean in the modern age.

The meaning of camps

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has claimed that in the same way that the 18th century was the century of reason and the 19th that of industry, so the 20th century was the ‘century of camps’. Far from being irruptions of medieval barbarism or irrationality, Bauman argues that concentration camps were not only products of modernity—means–ends thinking, technological knowhow, bureaucracy, division of labour, professionalization, control over nature, and human nature specifically—but had their own ‘sinister rationality’. They performed three vital jobs: as laboratories to explore new techniques of domination; as schools for cruelty; and as ‘swords over the heads of those remaining on the other side of the barbed-wire fence’, who would thus remain quiescent for fear of ending up in a camp themselves. These claims can be supported by the empirical literature on Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and other situations where concentration camps have been deployed. But Bauman goes further and makes the camps into a synecdoche of the modern world. ‘The camps,’ he writes:

were distillations of an essence diluted elsewhere, condensations of totalitarian domination and its corollary, the superfluity of man, in a pure form difficult or impossible to achieve elsewhere. The camps were patterns and blueprints for the totalitarian society, that modern dream of total order, domination, and mastery run wild, cleansed of the last vestiges of that wayward and unpredictable human freedom, spontaneity and unpredictability that held it back. The camps were testing grounds for societies run as concentration camps.

(‘A Century of Camps?’, pp. 274–5)

This is a sort of sociological rendering of Agamben’s philosophical argument that concentration camps reveal the hidden truth of the modern world. Unlike Agamben, however, Bauman sees camps as one logical culmination of modernity rather than the necessary expression of the truth of the modern state per se—a position which has left many perplexed by Agamben’s seeming pessimism and apparent unwillingness to distinguish between totalitarian and democratic societies. In Bauman’s view, the camps were invented to control human nature and—following Arendt—to make human beings superfluous. They were thus products or logical outcomes of Enlightenment thinking since the dream of mastery over nature is precisely an Enlightenment dream. This means that for Bauman camps go hand in hand with modernity; they are the clearest expression of the modern state’s potential for domination.

In some ways, Bauman is quite right: as we have seen most clearly with the Gulag, camps often go hand in hand with social restructuring or, more relevantly, breakneck economic development. The conveniently timed programme of dekulakization allowed the 1929 order to expand the special settlements to take effect; thereafter economic modernization and concentration camps went hand in hand in the Soviet Union. In that sense, Bauman is correct to note that concentration camps are not radically separated from ‘normal’ society but a logical extension of it. Concentration camps are thus ‘total institutions’, as described by sociologist Erving Goffman, places such as monasteries, asylums, or prisons where those inside are tightly regulated, sometimes involuntarily, by specific rules. Those inside the ‘total institution’ can adapt, according to Goffman, in one of four ways: regression (retreating into the self), resistance (actively fighting the system), colonization (learning to cope in the institution), or conversion (adopting the mentality of the guards). On this reading, concentration camps are like ordinary society in that certain rules apply and inmates’ ability to survive depends on how well they can adapt their pre-existing values and mores (what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls habitus) to the requirements of camp life.

Yet there is something oddly comforting about Bauman’s argument that camps are an expression of modernity, with its stress on instrumental rationality, bureaucratic officialdom, and the divorce of the moral from the technological. There is something equally comforting about Goffman’s notion of a ‘total institution’ that represents simply a more extreme, repressive version of familiar institutions. Both theories permit a critique of rules of socialization, science, and rationality that shields us from the more violent and wild aspects of this history. Their focus is more on a critique of society than on understanding concentration camps.

There are arguments in Bauman’s favour: when one looks at camps in colonial settings, one can easily argue that they represent the power of the modern state enforcing its rule on unwilling ‘natives’, even if such policies actually testify to the colonial state’s weakness in terms of its ability to rule effectively—the turn to force indicates a lack of legitimacy. In the Soviet Union, one can show that economic modernization and the Gulag were inseparable. Only after the Stalinist period, when more technical industries became significant, were the armies of forced woodcutters and railway builders surplus to requirements. In many cases, such as Franco’s Spain, terror went hand in hand with the notion that work would redeem the ‘feeble-minded Reds’. In the case of Bosnia, however, the camps served no purpose except terror; in the Third Reich concentration camps served different purposes at different times: terror and the elimination of real or possible opposition; getting rid of ‘asocial elements’; holding foreign POWs, especially politically suspect persons; involvement in the Holocaust; slave labour. In all cases, including in Kenya, Malaya, and Algeria, concentration camps have an air of madness about them that is not captured by Bauman’s description.

In the abstract, concentration camps might appear to be the logical conclusion of modernity, if by that is meant an indefinite extension of state power and a belief in ‘scientific’ solutions to social ‘problems’. But apart from the fact that from the Soviet Union to the Nazi war economy slave labour cost more to administer than it produced, concentration camps have always been about more than modernization. They are places of punishment, of discipline, where specific regimes’ world views are actualized. These world views need not be ‘modern’ in Bauman’s sense, which equates modernity with technology and bureaucracy. Rather, they are ‘modern’ in the sense that the modern age also intensified and canalized paranoid fantasies about racial and political ‘others’—ideas which long predated the modern age but which were expressed in new ways under modern conditions. Concentration camps, as Arendt noted, are places of terror, experiments in eradicating ‘the human’ from human beings. Camps are tools of the modern state but they are hardly the most ‘rational’ use of resources or the most logical tool of nation-building. There is something else going on.

That something else is the way in which the terror of concentration camps exceeds their rational use and even the thought-out desire for terror and revenge on the part of those who create them. There is an aspect of concentration camps that simply cannot be captured by describing them as manifestations of ‘absolute power’ or as the ‘nomos of the modern’. The camp is a product of modernity but also embodies a desire to overthrow rationality: a desire to abandon all limits, to transgress the moral law, and to engage in a kind of organized frenzy. This madness of the camps is such that even good communists reached instinctively for the theological terminology: as Eugenia Ginzburg left her first prison, she noted that from the time of her arrest: ‘Everything since then had consisted only of my wanderings through hell. Or could it be purgatory?’

This is where we can see similarities but also crucial differences between sweatshops, internment camps for asylum seekers, and refugee camps on the one hand and concentration camps in violent colonial and totalitarian states on the other, with places like Guantánamo Bay, an extraterritorial site where the law has been suspended, falling somewhere in between. The fact is that there is no simple definition of concentration camps; rather, they exist on a continuum of carceral practices, including detention centres, internment camps, prisons, ghettos, leper colonies, asylums, and other sites of exclusion. It is probable that practices developed in one have been learned and adapted in others—some authors claim, for example, that CIA practices in Guantánamo derive from torture practices first used in Nazi camps.

Yet the fact that we might be offended by, for example, the herding of illegal immigrants into a stadium (as the Italian police did in 1991 with Albanians) or by zones d’attentes in French airports should not mislead us into thinking that Bari or Charles de Gaulle Airport are equivalent to Auschwitz. Likewise, the inhabitants of Gaza are trapped in a territory that they ultimately do not control and where they suffer all manner of deprivations; but calling the Gaza Strip a concentration camp is actually a lazy way of trying to capture the specific nature of the day-to-day negotiation of power between Israeli occupation and supposed Palestinian self-government—the state of exception is a regularly imposed but not permanent feature of life there. The inhabitants of asylum seekers’ detention centres are removed from the human ‘circle of obligation’; they are treated, in Arendt’s terms, as if they no longer exist. But the rule of law has not entirely been suspended in their case. It is certainly objectionable that people who have fled their countries and are already highly vulnerable should be locked up and treated as suspects instead of being permitted to contribute to the country in which they are seeking asylum; the fact that they sometimes have to wait for years before being either released or deported is shameful and is an abuse of legal process. They are very close to falling into Arendt’s category of the superfluous stateless person from whom ‘the right to have rights’ has been removed. But not quite: they can be legally represented and the law which mocks them sometimes also produces decisions in their favour. Thus, even if we want to retain the name ‘concentration camps’ to describe all of the institutions discussed in this book—from the South African camps to the Gulag to Guantánamo—we have to recognize that the term encompasses a multitude of realities. Concentration camps throughout the 20th and 21st centuries are by no means all the same, with respect either to the degree of violence that characterizes them or the extent to which their inmates are abandoned by the authorities. And if we do not want to use the term so liberally, it is important that that decision should not be taken to mean that we condone institutions that we do not consider to be concentration camps.

The crucial characteristic of a concentration camp is not whether it has barbed wire, fences, or watchtowers; it is, rather, the gathering of civilians, defined by a regime as de facto ‘enemies’, in order to hold them against their will without charge in a place where the rule of law has been suspended. Internment camps for political prisoners and detention centres for asylum seekers are places where those inside are held against their will but not places, at least in theory, where the law does not apply—although it might well be bent somewhat. Even Guantánamo, which is regularly called a concentration camp, can at least be criticized by lawyers and human rights campaigners in the US and elsewhere. But the difference is one of degree, and as we have seen in this book, whose examples range from vast ‘special settlements’ without fixed border fences to death camps, any attempt to provide a fixed definition quickly runs into problems, even as we can see that such places cannot simply be reduced to ‘the same’. We are returned to Arendt’s theological continuum of Hades, purgatory, and hell: we can see that some camps are worse than others, but unlike in Arendt’s scheme (purgatory and hell are separate realms, even if one can move between them) it is not clear exactly where one sort of camp merges with the next.

What is missing from Bauman’s description of concentration camps—as opposed to any of the other sort of institutions discussed here—is the absence of rationality that one finds alongside ‘modern’ structures. ‘Hier ist kein warum’ (There is no why here) responded a guard to Primo Levi when he prevented Levi from sucking on an icicle in Auschwitz; the absurd accusations—bourgeois wrecking and the like—that filled up the Soviet Gulag are just as preposterous. We need an analysis which combines the ‘how’ of the concentration camps (bureaucracy, rationality, and so on) with the ‘why’ they are there in the first place (paranoid fears of fifth columnists, race traitors, and so on). In concentration camps there is a seemingly insane abandonment of reality accompanied by the most brutal and unceasing reminders to the inmates that what they are suffering is inescapably real. In terms of accusations and judgements we are in the realm of the fantastical; in terms of punishment, in the all too human realm of a harsh reality.

In 1949, American critic Isaac Rosenfeld published an article in Partisan Review entitled ‘The Meaning of Terror’. In this cry of despair, Rosenfeld set out his opinion that the world had been forever sullied:

Terror is today the main reality, because it is the model reality. The concentration camp is the model educational system and the model form of government. War is the model enterprise and the model form of communality. These are abstract propositions, but even so they are obvious; when we fill them in with experience they are overwhelming.

(Preserving the Hunger, p. 133)

What does it mean to say that the concentration camp is the ‘model form of government’? Surely this is no more than a case of post-war shock? And yet the recurrence of concentration camps, states’ ready recourse to them in all parts of the world in different political, geographical, and cultural settings, suggests that Rosenfeld might have been on to something.

What Rosenfeld captured was the way in which the concentration camp became an expression of modern states at a certain moment in time. The German philosopher Karl Jaspers wrote that:

This reality of concentration camps, this circular movement of torturers and tortures, this loss of humanity threatens human survival in the future. Confronted with the reality of the concentration camps, we are unable to speak. This is a greater danger than the atom bomb, since it represents a threat to the human soul (cited in Ivanova).

That may be true but it is also ahistorical. Concentration camps emerged in the early 20th century as modern states emerged out of older empires, sustained by ideas of nationalism and biological metaphors defining the healthy and valuable on the one hand and the polluting and degenerate on the other.

It is in fact possible to historicize the emergence of the concentration camp and to explain why, for all the continuities with social and colonial practices of preceding centuries, the term and the phenomenon arose when they did. The concept of the concentration camp, Javier Rodrigo reminds us, ‘refers not so much to a place with a set of uniform features over space and time as to the status that has been conferred on such a place’. As he notes, concentration camps emerged in many places around the same time, but with distinct local variations, meaning that there is a ‘cumulative history’ of concentration camps, ‘with lessons learned, discontinuities and adaptations to the contexts in which they developed’. Rodrigo provides a clear statement of the context in which concentration camps emerged in the wake of colonial wars and the First World War:

The concentration camps symbolized the transformation and radicalization of the politics of occupation, which extended from the treatment of political prisoners and prisoners of war to the deportation of civilians, from forced labour in extreme conditions to the hunger and misery occupied peoples were also subjected to. Concentration camps also came to serve as a space for social cleansing and internal politics.

(‘Exploitation, Fascist Violence’, p. 563)

Concentration camps were ways of keeping the unwanted elements at bay and, furthermore, putting them to use: not only through their labour (which was rarely very productive) but as a warning to wider society too. ‘The camp,’ Richard Overy writes, ‘reflected political and social insecurities, and a public discourse of fear, part real, part sustained by regimes built on warring ideologies.’ The concentration camp was an expression of the centralization of terror, one of the key characteristics of the modern state in the age of nationalism and technology.

The memory of the camps

When British troops arrived at Belsen, not only did they liberate the camp but they also filmed that liberation. The ceasefire negotiations on 15 April 1945 were recorded by the British Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU), and the next day it began a planned two-week coverage on Belsen. In fact, many members of the unit stayed longer, producing what Rainer Schulze has called ‘a large collection of what constitutes some of the most amazing, moving and at the same time distressing images of the Second World War’. The film of the liberation was never completed and has recently been restored and finished by the Imperial War Museum in London, and released with its original title, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey. The sober title reflects the serious nature of the contents, and the decision to restore it and complete the work of the unit tells us that the memory of Belsen, and the Nazi camps in general, remains as strong in contemporary European culture as it has been since the end of the war.

This is a reminder that concentration camps have an afterlife. As we have seen, some of the Nazi camps were used again as DP camps or camps for political prisoners; others fell into disrepair and were ignored by the locals. But over time, many were turned into museums so that today there is still a landscape of camps across Europe, only now they are tourist sites or Gedenkstätten—sites of warning and contemplation. This process of musealization has always been contested, and former camp sites’ meanings change over time. Buchenwald, for example, was turned by the communist authorities into the GDR’s premier memorial to anti-fascism, its monuments depicting the solidarity of the underground communist resistance and perpetuating the myth of the camp’s ‘auto-liberation’ from Nazi rule—a myth because the role of the US Army was crucial. In Auschwitz, the ‘national memorials’ in the main camp (Auschwitz I) were used by the communist countries to defend their anti-fascist record—even countries which were allied to Germany—and by the Austrians to promote the lie that they were the ‘first victims of National Socialism’ rather than enthusiastic supports of Hitler. Camps are not set in aspic; they continue to evolve as debates over restoration, ‘authenticity’, and changing exhibitions compete with the pressing need for tourist facilities.

The Nazi camps, more than any others, have been represented in every genre of art. From serious documentary (The World at War; The Nazis: A Warning from History) to children’s films (Chicken Run) and TV drama (Band of Brothers), to novels and poetry, ranging from the restrained and severe (Ida Fink, Paul Celan, Dan Pagis) to the sensationalist (Sophie’s Choice), children’s books (Billy the Kid, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas), comics (Maus, Rain, the Auschwitz Museum’s Episodes from Auschwitz publications, and many didactic as well as scandalous publications), to gore fest films (Dead Snow, Uwe Boll’s Auschwitz), and arthouse films (The Grey Zone, Son of Saul), to sculpture, music, and other sorts of performance, including public readings of Holocaust texts (Pinter et al.), performance art (Józef Szajna), and theatre (Tadeusz Kantor, Joshua Sobol, etc.). The camps have been depicted in Lego, in vast models (Chapman Brothers), and as backdrops to all varieties of stories and genres. Whether this ubiquitous representation of the Nazi camps constitutes a serious-minded engagement with the past or a massive banalization of it remains disputed.

What is so striking about this state of affairs is the extent to which the Nazi camps stand in for all camps. What has happened to concentration camps elsewhere? Some have been turned into museums, with a greater or lesser degree of taste. Many have disappeared altogether. The desert camp of Chacabuco in Chile was given a facelift and used as workers’ barracks. Few of the camps of the Gulag have been turned into memorial sites, especially now that the Soviet Union does duty, stripped of its Stalinist ideology, as a reminder of Russian ‘greatness’. In Spain, Mariano Rajoy’s government stopped all funding to the associations that uncover and memorialize atrocity sites of Francoist repression in 2013. There have been efforts to memorialize camp sites in Namibia, Latin America, France, and elsewhere. But most of the concentration camps that characterized the 20th century have gone. Besides, not even all the Nazi camps are memorialized. The massive industrial facilities of Christianstadt, a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen, not far from what is today Wrocław in western Poland (formerly Breslau), are falling into ruin in the forest, largely inaccessible (see Figure 10). We remember the camps we want to remember in ways that suit us.

10. Ruins at Christianstadt.

When the journalist Alan Moorehead published Eclipse, his book about the defeat of Germany in late 1945, he wrote that probably the least blameworthy of the Germans was the ‘unpolitical boy’ who was forced to don a uniform and fight and die for the Third Reich. ‘There is only one thing possible that one can do for him now,’ wrote Moorehead: ‘be vigilant to snap the long chains that lead to the future Belsens before they grow too long.’

Given the history of the postwar period, we might wonder whether the world has been engaged in strengthening and tightening those long chains rather than snapping them. There seems little likelihood of future Belsens in Europe, at least for the foreseeable future—though we thought that before Omarska too. But the Chinese Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward, the internment of Jewish DPs illegally seeking entry into Palestine on British-controlled Cyprus, the holding of suspected anti-colonial rebels in Malaya and Kenya, the continued existence of the Gulag in the post-war Soviet Union, even in its scaled-down version, the Khmer Rouge’s ‘country-as-concentration camp’, the rape camps of Bosnia, Guantánamo Bay’s suspension of the rule of law, the still-existing North Korean camp system, to name just the most obvious, all suggest that concentration camps have not only not disappeared; they have become an all-too-ubiquitous characteristic of our world. And no surprise; we live in a world where inter-state competition encourages inter-community tensions, where ‘the war on terror’ breeds the thing it is supposedly suppressing, where legal protection of human rights and the commemoration of ‘heroes of the Holocaust’ such as Sir Nicholas Winton go hand in hand with contempt for refugees, who are pushed into makeshift camps or interned in ‘detention centres’. Concentration camps are the compressed and condensed values of the state when it feels itself most threatened.

Could it be that the collective memory of the Nazi camps, cultivated in the West but now widely shared across the world and endorsed by the UN in events such as Holocaust Memorial Day (27 January, the date of the liberation of Auschwitz), has diverted our attention from other atrocities? Moorehead predicted something like this in 1945:

A shudder of horror went round the world when the news of these concentration camps was published, but only I think because of the special interest and the special moment in the war. We were engrossed with Germany, and it is perhaps not too subtle to say that since Germany was manifestly beaten people wanted to have a justification for their fight, a proof that they were engaged against evil. From the German point of view Belsen was perfectly mistimed. Worse camps existed in Poland and we took no notice. Dachau was described in the late nineteen-thirties and we did not want to hear. In the midst of the war three-quarters of a million Indians starved in Bengal because shipping was wanted in other parts, and we were bored.

The last living patient has been evacuated from Belsen. The hateful buildings have been burned down. The physical evidence of all those horrible places will soon have been wiped out. Only the mental danger remains. The danger of indifference.

(Eclipse, p. 229)

It would be wrong to argue that Holocaust memory has been deliberately cultivated to place the focus on suffering Jews at the expense of others. The idea that there is a ‘Holocaust industry’ is a slander against those whose enduring interest in the murder of the Jews stems from a very human reaction to so terrible a crime. Yet the enormity of the Nazi murder of the Jews and our understandable fascination with it does mean that other cases of genocide or massive human rights abuse are not always properly understood, especially if they do not look like the Holocaust. It means too that the term ‘concentration camps’ has come to denote places like Dachau when in fact most of them were quite different, with the result that propagandists exploit the association to overstate the extent of ‘their’ suffering on the one hand, or that the term is rejected in cases other than Nazi Germany on the other hand. More problematic still, the proliferation of concentration camps since the end of the Second World War suggests that Moorehead was right: indifference towards the suffering of others is as common now, in the age of immediately available electronic news media, as it was between the wars. Survivor of the Nazi camps Boris Pahor claimed that modern Europeans are ‘basically thoughtless and cowardly’, that they have become used to a comfortable existence. ‘Today’s standardized man,’ he surmised, ‘may be awakened, who knows, only by some new lay order that dons striped camp burlaps and floods the capitals of our countries, unsettling the complacency of shopping malls with the harsh clatter of their wooden clogs.’ The response from most of Europe’s leaders in 2015 as Syrian refugees sought assistance in fleeing one of the most destructive wars in recent history suggests that Pahor may have been too optimistic.

The majority of the world’s population does not live in concentration camps—that claim is more polemic or a call to action than an accurate description of the facts. But that many commentators lay claim to the concentration camp metaphor when discussing Bangladeshi textile factories, Guantánamo Bay, the Gaza Strip, or even the global south as a whole should at least lead us to consider the inequalities that define our world and the threat of greater conflict in an age of accelerating climate change. The claim that the camp could be ‘our’ future or that the camp represents the secret inner workings of the modern state, if not entirely persuasive because it is ahistorical, should certainly make us pause for thought before deciding that concentration camps are the products merely of ‘mad’ dictators and their blind followers.

States can do bad things as well as good: they can destroy people’s lives in concentration camps but they can also improve lives. They can nurture populations through education, health programmes, and access to welfare in a way that creates critically engaged citizens rather than downtrodden, suspiciously regarded subjects. There is more to the history of the 20th century than its depressing abominations in centres of detention and destruction. At the start of the 21st century one could be forgiven, however, for thinking that those beneficial aspects of the state have been severely attenuated for many of the inhabitants of our planet. And those of us who are more fortunate—who live in places where a vestige of the post-war social democratic settlement still survives—might do well to watch our backs.