EIGHT

HARVEY ROBINSON:

A Risky Sting

It was rare for patrol officers to be in this position, but for two weeks Brian Lewis and Ed Bachert had been sitting up all night in separate houses in the hope of stopping a roving killer. At each place lived the victim of a brutal attack, and on Bachert’s watch in the middle of the night, someone had banged on the door but tried nothing more. Lewis wondered if the house where he was staying would be next.

The killer had already returned to the place at least once, before the surveillance, stealing a gun. He knew that someone who lived there could identify him, so Lewis had been watching throughout the night. If no one showed up soon, the surveillance would end, but with a few nights remaining, Lewis knew he still had a chance to stop the man who had already killed three women in the area.

Allentown, Pennsylvania, in the peaceful Lehigh Valley, seemed an unlikely place for a serial killer, but during the 1980s and 1990s, such crimes had increased across the country. There had been several serial killers in Philadelphia, an hour to the south. Then, in quick succession in 1993, a man abducted a girl and also entered four different homes, killing three people and assaulting two more, including a five-year-old child. The woman Lewis was now protecting would probably have died had not a neighbor fortuitously stepped in.

It was now the twelfth night on his watch. He had a few magazines to help keep himself alert, and lights burned as enticement at the two windows left open. Around 1:20 a.m., Lewis heard a noise and tensed to listen. Someone was testing the patio door.

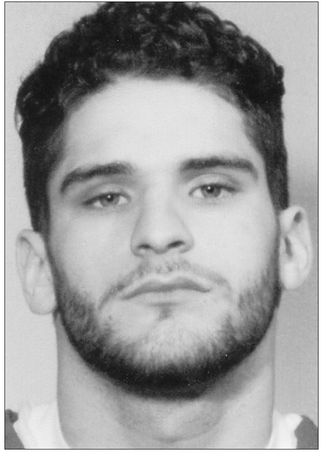

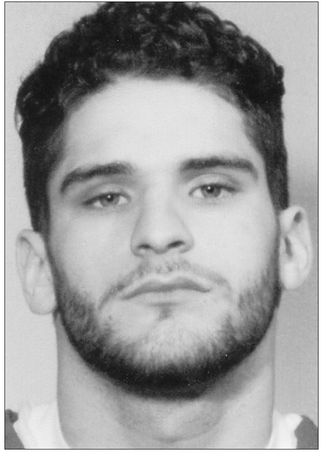

Harvey Robinson, whose series of rape/murders struck fear into the small town of Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 1992. Allentown Police Department

This was it! The end of a terror spree that had started eighteen months before.

Harming the Innocent

Mary Burghardt, twenty-nine, suffered from a mental illness and could not function without assistance. On August 7, 1992, she reported that someone had cut through a screen door and entered her apartment. Two days later, she was unaware that a young man was watching her through a window as she began to undress. She entered the living room with some milk and cookies, and suddenly the same man tore through the front window screen and came at her, smacking her so hard in the head that he knocked off her glasses and spattered the wall with her blood. Although trapped, she managed to run past this intruder and get to a room where she could pound on the wall and scream for help. No one came.

The intruder turned on the television, increasing the volume. With his prey trapped and helpless, he bludgeoned her with a blunt weapon until she fell to the floor; he kept hitting her in a rage until he had delivered thirty-seven blows to her head, some so strong that strands of her hair were driven into the skull fractures. Once he was certain she was dead, he looked for a pair of her panties in a drawer and then used them to masturbate over her prostrate body. Then he left through a back door. Despite being covered in blood, he walked through a field and returned to his home, about four blocks away.

Soon he was detained for a lesser crime and sent to juvenile detention. When he was released eight months later, on June 9, 1993, he drove back to his victim’s neighborhood and spotted a girl on a bike delivering papers. He grabbed her in broad daylight.

A woman on East Gordon Street, waiting for her Morning Call, looked out her window and saw the newspaper cart abandoned between two parked cars. It was uncharacteristic of carrier Charlotte Schmoyer to be negligent, so the woman phoned the police. They called Schmoyer’s supervisor, who said he had not heard from her and could not locate her. When officers searched the area, they located the girl’s bicycle and portable radio, but not her. She was also not home.

D.A. Robert Steinberg accompanied the police as they followed a tip to a wooded area at the East Side Reservoir. They discovered a trail of blood leading from the parking lot and Steinberg noted a discarded shoe. Then one searcher called out from the woods that he had found the fifteen-year-old’s body, covered with dead leaves and several heavy logs. No one had seen the incident, but a resident recalled a light blue car in the area, while someone else reported a similar vehicle at the reservoir.

An autopsy revealed that Schmoyer had been stabbed twenty-two times in the back and neck before her throat was slashed open. She had also been raped, and three superficial cuts indicated that a knife was held to her throat during her ordeal. A pubic hair was picked off her navy sweatshirt and a head hair from her knee.

Yet there were no real leads and no clues from the scene of the abduction or murder, so this shocking crime went unsolved. Residents wondered if the girl had known her abductor or if the incident had involved a stranger’s random attack. No one yet realized that Charlotte Schmoyer was actually the second victim of the killer.

Early Warning

Denise Sam-Cali, thirty-seven, lived on the East Side of Allentown, not far from where Charlotte had been abducted, and she usually walked a mile each morning to the limousine and bus service she owned with her husband, John. She learned only later that a young man had spotted and followed her.

Denise and John went away for a few days and returned on June 17. To their annoyance, they found the back door to their home slightly open. John went inside to look around, but saw no immediate evidence of a burglary. Nevertheless, someone had clearly been there, as a whiskey bottle had been moved and they found a dirty footprint on the couch. Then John checked his gun collection, which he kept in a special bag in the closet, and was stunned to discover the bag gone. He phoned the police, who were unable to locate the stolen collection.

For protection, John quickly purchased two more guns, including one for Denise. He felt frightened knowing that someone not only had those guns but had also entered his home, and violated it. Denise did her best to learn how to shoot, although she hoped she’d never need to defend herself in this manner. The couple had reason to grow even more worried when another incident occurred in their neighborhood.

On June 20, an intruder entered the home of a woman who was in bed on the second floor with her boyfriend. Her five-year-old daughter slept in a bedroom nearby, and the intruder entered and choked her into unconsciousness, carrying her by her neck downstairs. She revived and tried to scream, but he dumped her headfirst into a laundry basket full of towels and dirty clothes. While she was unable to move or scream, he raped her. Then he choked her again and she passed out. At this point, he left the residence and went home, just two blocks away.

Early the following morning, the girl woke her mother to tell her what had happened, so the woman’s boyfriend checked downstairs and found that a window screen had been removed. The victim’s mother saw small hemorrhages in the child’s eyes, a sign of asphyxia. She took her to a doctor who found that she had been choked till some blood vessels had burst and had been sexually attacked. The intruder had probably intended to kill her.

With one victim grabbed outside and two accosted inside their homes, Allentown residents were alarmed. More people began locking their doors and windows, despite the summer heat, but this did not stop the marauder. After a month, he struck again.

Failed Assault

Denise Sam-Cali was home alone on June 28, because John was on a business trip. She had come in late after visiting her aunt down the street, and gone to bed. Although she had practiced with the new gun and was able to hold it steady, she still did not feel safe. Opening the bedroom window for some fresh air, she undressed and crawled under the sheets.

But she was restless and unable to sleep. She lay in bed listening to the night noises outside and hoping that John would come home. Suddenly she caught her breath. She was sure she’d heard something inside the house that sounded like crackling paper. She sat up and shouted, “Who’s there?” She hoped whoever it was believed he had entered an empty house, like before, and that he would be startled to realize someone was home and decide to just leave. But the place was silent.

Deciding she’d be safer with a neighbor, Denise jumped out of bed, grabbed a comforter to cover herself, and ran down the hall. To her horror, a man emerged from a walk-in closet with a knife in his hand. Racing away, she went for the door, but he got there, too, and grabbed her arm. He tried to stab her in the face, cutting her lip, but she knocked the knife away and struggled to get out. Although he still had a firm grip on her arm, she managed to break free, get outside, and run. On the lawn, the man caught her by the hair and threw her to the ground. She tried to scream but nothing more than a gurgle came out. This intruder was adept at pinning a woman down while he prepared to rape her. He began to strangle her, and she later recalled being punched four times in the face. Denise bit her attacker hard and cried out, but he choked her until she blacked out.

But she was lucky. A neighbor turned on a floodlight, which frightened off the attacker. Denise regained consciousness and managed to crawl back into her home and call 911. The police arrived and took her to a hospital. It was clear from her injuries that she would need hospitalization and possibly plastic surgery. She let a nurse process her with a rape kit for evidence, although she was not certain she’d been raped. As doctors attended to her bruised face and the strangulation marks on her neck, she was aware how lucky she was to be alive. Her assailant had certainly intended to kill her. The police soon found the knife he had grabbed in the house, wrapped in a napkin and left behind on the floor.

John was horrified when he learned what had happened. He made immediate plans to secure their home but insisted that Denise stay with one of her relatives. When she was able, she gave the police a description of her attacker: he’d been white, about five-foot-seven, muscular, young, and clean-shaven. His eyes, she recalled, were filled with rage. It would take a session with a hypnotist to help her bring forth enough details from that night to realize that she had indeed been raped.

When the newspaper reported that Denise had survived the attack, she knew she would never be safe in her home as long as this killer was free. He would certainly be afraid that she would recognize him, and given the fact that most of his assaults were in her neighborhood, it was likely he lived there.

John installed an alarm system, but once again the intruder managed to break in. During the night of July 18, someone set off the alarm and left in haste by the back door before the Calis saw him. However, they found several things missing in the morning, including some luggage and a handgun left on a table.

The D.A. believed that the rapist would certainly revisit the home again to silence the witness and he wondered if he could work this to his advantage. It would mean the Calis would have to remain in the home, vulnerable, to lure the man back, but he assured them that they would have police protection every night. They bravely agreed to the plan. Denise wanted relief from the unrelenting nightmares she’d been having since her attack. This man, she believed, had victimized her and would continue to exert power over her until she did something to take it back. She figured that if the intruder managed to break in and get past the police guard, she’d be ready to blast him with her own gun. John would be there, too.

But before this plan was set in motion, another woman was killed.

The Allentown serial killer had spotted a large-boned, overweight white woman, and he’d followed her until he saw where she lived. Jessica Jean Fortney was forty-seven, and she lived with her grown daughter, son-in-law, and their seven-year-old child. On July 14, these three were asleep on the second floor, with loud fans cooling the place, when the man entered and attacked Fortney in the living room, breaking her nose with a weapon. Then he raped and strangled her, leaving her blood-covered body on the sofa beneath a blanket. But this time, there was a witness. Fortney’s grandchild had seen the assault from her bedroom. Her description matched what Denise Sam-Cali had said about her attacker.

D.A. Steinberg realized there was a dangerous serial sex killer at large in Allentown who was striking quickly, and often. These crimes had all been committed in the same general area, and except for the newspaper girl, all the victims were attacked inside their homes, after the offender had entered through a window.

The police could only hope the killer would try yet again to silence the one woman who had survived. Their fear was that he would begin to roam a larger area, as his latest crime, over a mile away from the others, suggested. Allentown was close to the urban communities of Bethlehem and Easton, as well as a cluster of smaller towns within a fifteen-minute driving distance. If the killer had a car, as it seemed he did, and was feeling the heat, he might just go farther out. But on July 31, he made a major miscalculation.

The Sting

Officer Brian Lewis, a patrolman with just over three years’ experience, was assigned to the Sam-Cali home, a single-story ranch house, while another officer, Ed Bachert, went to the house where the five-year-old girl had been accosted. The assignment was to last two weeks.

They generally arrived around eleven-thirty in the evening and remained until six in the morning. Lewis’s routine was to go around and secure all the doors, but leave two casement windows in the front room open, because the intruder had used this entry before. No one knew if this plan would work, but the officers continued to watch, night after night. Then, on the twelfth night, around 1:20 a.m., Lewis heard a distinctive noise: someone was prying at the patio door.

“I was right inside the front door,” he related, “against the wall. I knew all the doors were secure, and the patio door even had a piece of wood inserted to prevent it from opening. The rear door had a dead bolt as well. I was positioned where I could see the living room and the casement windows. When I heard a big yank on the patio door, it was probably the best adrenaline rush of my life. I knew this was it!” An outside light showed him a shadowy figure moving around, so unlike the incident a few nights before at the other house, this person was sticking around.

“My instructions were to allow him to come into the home and I would then notify others with the police radio.” To accomplish this, Lewis would pull a pin out of the radio, which sent a signal to the communication center that he was in need of immediate assistance.

“I then heard the back doorknob being turned, and a few minutes later, there was another tug on the patio door. I got my gun and flashlight out, and I went to kneel behind the couch.” He’d never before shot at a person, so he was understandably tense. “The next thing I saw was the doorknob turning on the front door, and I’m thinking, did I lock that? I was only about two feet away from it. But it didn’t open. By that time, my adrenaline had subsided and I was thinking, we’ve waited this long, don’t screw it up.”

He saw the screen on one casement window being prodded, and he expected a knife to come through to cut it, “but it just kept getting pushed and finally it pushed in. I saw a hand with a big rubber glove like the kind that janitors use, and it lowered that screen onto the couch below.”

At this point, he had not yet pulled the pin on his radio and he did not dare try to talk into it, lest he alert the intruder and scare him off.

“The next thing I see is a face coming through the window. Because the area was lit by a table lamp, I saw a profile. He had a good-size nose. Then the face turned and looked in my direction and then looked away. The next thing I saw was an arm and leg come in. I ducked behind the couch to completely hide and pulled my pin. I heard someone inside the living room, so I stood up and identified myself, and said, ‘Freeze!’ ”

For a moment, the two of them were face-to-face in the small living room. The intruder had a gun on his waistband and he reached for it, so Lewis fired a shot from his Smith & Wesson six-shot revolver. “My flashlight fell to the floor and he dove into the kitchen area, where it was dark. I moved to the doorway and saw a muzzle flash coming back at me. I realized we were in a battle, so I stepped to the left of the doorway, which was a wall, to get some cover. I immediately stepped back to the doorway and fired a shot at where I believed he was, on the floor. By the time I’d fired, he had moved to the back door. I could hear him but I couldn’t see, so I fired my next four shots at where I believed he was.”

Now Lewis was out of ammo, so he had to reload. He pulled back to where he had cover, but thought, I can’t reload here. He’s right there, he’s got a gun. He recalled an incident in Allentown where a sheriff’s deputy was shot and killed while reloading, so he retreated toward the back bedroom. He knew the couple was in there, so he yelled out, “Don’t shoot, it’s me!”

Frightened by all the commotion, John and Denise were standing on either side of the bed, holding guns. Lewis got on the radio to tell other officers what was happening. He heard the intruder banging on the dead-bolted back door and kitchen walls, trying desperately to get out. The house was literally shaking. Lewis instructed the couple to stay out of the way as he reloaded and prepared to face the gunman again.

But suddenly the place went quiet. It felt too still.

Lewis edged cautiously toward the kitchen, uncertain what to expect and keeping his gun ready. As he drew closer, he anticipated that the guy might spring out at him or fire from some dark area. He neared the door to the kitchen, tense, his heart pounding, but when he still heard nothing, he wondered if the intruder had found a way out. Then he saw it: several broken windows on the wooden door. “They were just ripped out of the door.”

The man had managed to force his way out and slip away. Lewis went outside, hoping the vice officers had caught him, but there had been an unfortunate delay. When his backup had heard the shots and received the emergency signal, they’d been several blocks away. Thus the intruder had eluded them.

Nevertheless, an examination of the door frame indicated that he’d left blood behind. Lewis thought that perhaps he’d winged the guy and they might have a blood trail to follow. Even better, the intruder might seek medical attention, and blood samples at the hospital would match those in the Calis’ house. He also noticed that one of his shots had hit a can of baked beans, exploding its contents into the room. Another officer held up the can and said to Lewis, “You’re never gonna live this one down.” However, it would prove to be a fortuitous hit.

The entire episode had lasted about twenty minutes. Calls were made to the consortium of Lehigh Valley hospitals to be on the lookout for anyone coming in with a bad cut from glass or a bullet wound. This was the closest the police had come to nailing this offender and they were excited but cautious. There was no certainty in such situations.

Several hours went by without a word. It seemed that the killer had eluded them, but around 3:30 a.m., police learned that a young man had shown up at the Lehigh Valley Hospital’s ER to get treated. His arm and leg were bleeding badly. He seemed to realize that he’d walked into a trap and quickly headed for an exit without talking to anyone, but he was stopped outside and detained.

Lewis arrived, but the light had been poor, so he couldn’t be sure it was the same man he’d seen in the home. The shoes looked the same, but that was no way to identify someone. However, inside the cruiser car, under different lighting, he was sure. This was the man who had shot at him hours earlier. His name, it turned out, was Harvey Miguel “Miggy” Robinson and he lived on the east side of town with his mother, Barbara Brown, only a few houses from where Ed Bachert had watched during the night.

Lewis learned that Robinson, only eighteen, had told his girlfriend he’d been hurt at a party and it was she who’d insisted he get medical treatment. So he’d gone to the hospital. Since the Sam-Cali residence was on the west side and the hospital across town, he might have believed no one would link him to the break-in.

What to Do with a Serial Killer

Robinson was booked and arraigned on multiple charges, including breaking and entering, burglary, aggravated assault, and attempted homicide. He was held in lieu of $1 million bail. On September 3, Denise Sam-Cali testified at his hearing that she could identify Robinson as the man who attacked her and she fully described her ordeal. He sat throughout the hearing with a glare on his face. Other evidence against him included Officer Lewis’s identification, a bite mark that Denise claimed to have made during her assault, black gloves found in his bedroom at his mother’s home, and the Colt .380 handgun stolen from the Calis, along with casings that matched those from two bullets fired on July 31 in their home.

The police worked hard to find evidence for the trials. They searched two cars, a light blue Ford Tempo GL belonging to Robinson’s mother, which was similar to the car seen in the neighborhood when Charlotte Schmoyer was abducted, and Robinson’s gray Dodge Laser SE. His blood was in both, indicating that he had driven them at different times on the night of the shoot-out, after he was cut. The cars were processed for fingerprints and other evidence. Searching his house, they located some baked beans from the can that Officer Lewis had shot open. They also found clothing, which Robinson had attempted to wash, that matched what Lewis had seen the intruder wearing.

For his arraignment, Robinson wore a bulletproof vest. Police had learned that between the Burghardt and Schmoyer murders, eight months apart, Robinson had been incarcerated for burglary but had no history of mental illness. Investigators believed that he had either known his victims or had stalked them in some manner before raping or killing them. He may have burglarized Burghardt’s apartment a few days before he killed her.

In December 1993, just after Robinson turned nineteen, the papers announced that DNA tests from his blood samples linked him via semen to the three rape/murders and the two rapes. In addition, his blood and hair were found on Schmoyer, and both the little girl he had raped and Denise Sam-Cali identified him as their attacker.

The Case

During a preliminary hearing on January 6, 1994, the prosecutors laid out the case against Robinson for multiple rapes and murders, among other charges. Eighteen witnesses were called, including Denise Sam-Cali once again, although the trial for her rape and attempted murder would be a separate proceeding.

D.A. Steinberg led the prosecution while Robinson’s family had hired David Nicholls, and Nicholls immediately questioned the validity of the DNA evidence. It was a common ploy for defense attorneys in those days, because while DNA analysis had been confirmed as a viable science, such attorneys hoped to win back some ground by questioning laboratory procedures and poor handling of evidence. Nicholls suggested possible problems with the technicians, exposure of the samples, questionable internal procedures, and the reliability of the test itself.

Supervisory Special Agent Harold Deadman, with the FBI lab, put the specimens through testing, along with specimens from other men in the area with a history of sex crimes, but only Robinson was a match for the samples retrieved from the victims. The state-police lab confirmed this with its own tests.

The first case to be decided involved Denise Sam-Cali. D.A. Steinberg told her that Robinson would plead guilty in return for a reduced sentence and no trial. She initially declined this offer, but, on April 13, accepted the terms. Semen samples removed from the victim shortly after she was attacked were matched via DNA analysis to Robinson, and she identified him as her attacker. In addition, he had a gun in his possession that he’d stolen from her house, and Officer Lewis identified him as the man with whom he’d had a shoot-out there.

Robinson said nothing during the hearing and his attorney called no one to speak on his behalf, although Robinson’s mother and half sister were present. Nicholls made it clear that the defendant had long been a troubled young man who’d had a difficult life. He offered no motive, but he did set forth the young man’s good qualities: a high IQ that allowed him to obtain his high school equivalency diploma when he was sixteen (and in juvenile detention) and a good relationship with a loving mother.

Steinberg told reporters afterward, “He is everything that is evil in society, all rolled up in one person.” But Nicholls asked for leniency and suggested that Robinson could be rehabilitated. Steinberg countered this with Robinson’s lengthy juvenile record and the threats he had made against other prisoners at the facility where he was currently detained. In fact, since the first grade (which he repeated) Robinson had been resistant to rules and aggressive toward others, and he’d committed his first juvenile offense, a theft, at the age of nine. Each time he was released from juvenile detention, he committed more antisocial acts and refused to take advantage of prosocial opportunities. Given this history and set of behavior patterns, his chances for rehabilitation seemed slim to nonexistent.

Despite Nicholls’s argument, Robinson was sentenced to forty to eighty years in state prison for the rape and assault of Denise Sam-Cali, and for burglarizing her home and shooting at a police officer. Nicholls then relinquished his duties, leaving it to a public defender to take on the murder cases. In the meantime, reporters were busy learning more about who this young offender was.

Robinson was biracial, although he normally passed for white, and his black-Hispanic father, who was dead, had been convicted of manslaughter. For that, he’d served a seven-year prison term. The man had frequently gotten drunk and quarreled with Barbara Brown, Robinson’s mother, sometimes hitting her.

(Robinson denied having been physically abused himself.) His parents divorced when he was three years old and he remained with his mother, although one source indicates that he idealized his father and occasionally saw him. Robinson’s older stepbrother had also spent time in prison.

Robinson had been an impulsive child with little ability to focus, a great deal of moodiness, and a hair-trigger temper. He was nine years old when he was first arrested, and over the next eight years, he piled up a dozen more arrests, mostly for theft and property crimes. He fought with authority figures, had a history of substance abuse, and had been diagnosed with conduct disorders that were precursors to an adult antisocial personality disorder.

The family frequently changed its residence, but Robinson spent many years on and off in different juvenile facilities. He once assaulted a male middle school teacher who was assigned to watch emotionally disturbed youths in the classroom, and female teachers reportedly felt threatened by him. He was fifteen when he committed his first known burglary, and two years later, he’d become a rapist and murderer.

Yet he did have his good points. At Dieruff High School, he wrestled, participated in cross-country sports, and played soccer and football, receiving trophies for his skill and ability. He was also a good student, excelling academically and earning awards for his essay writing. But awards and trophies, and even recommendations, are difficult to reconcile with a rash of rapes and brutally violent murders.

The Trial

Robinson was assigned a public defender, Carmen Marinelli, who, on July 24, requested three separate trials and a change of venue, because of the amount of publicity the case had garnered in the Lehigh Valley. Yet Steinberg hoped for a single trial, and he demonstrated the strong similarities of the three cases, all containing DNA links to Robinson. He called FBI analyst Stephen Etter to explain the indicators known to experts that the murders were the work of a sexually motivated serial killer. The judge considered both arguments and decided to hold one trial, in Allentown. James Burke was appointed to join the defense.

The prosecution lined up fifty witnesses to prove Robinson’s participation in all three murders. Along with blood and semen evidence against him, there had also been a sneaker impression on the face of one victim that was similar to sneakers that he’d worn. In addition, the strands of pubic and head hair found on Charlotte Schmoyer had been linked, microscopically, to Robinson. Denise Sam-Cali testified again, letting the jury know in a determined voice that Robinson was the man who had raped and assaulted her. He did not speak on his own behalf, despite his attorneys’ request that he do so.

The proceeding lasted three weeks, and on November 8, 1994, Harvey Miguel Robinson was convicted of the rapes and murders of Burghardt, Schmoyer, and Fortney. The jury was then sequestered in order to avoid outside pressure as they listened to evidence about how the defendant should be sentenced. His life was on the line.

During this phase, Robinson once again rejected his attorneys’ plea to testify on his own behalf, so the jury heard from other witnesses about his difficult life and multiple juvenile arrests. One side used these incidents to demonstrate his incorrigibility, while the other said Robinson had not yet had the chance to do better.

“If there ever was a case where the death penalty was warranted,” Steinberg was quoted as saying, “this is such a case.” He offered four aggravating circumstances: multiple victims, murder committed during other felonies, torture of the victims, and a history of violent aggression and threats.

Dr. Robert Sadoff, a forensic psychiatrist, testified for the defense. He indicated that Robinson suffered from a dependency on drugs and alcohol and had an antisocial personality disorder. He had also experienced visual and auditory hallucinations. It was not unusual to find petty juvenile crimes and aggression among children who later developed such problems, Sadoff stated, and he then suggested that Robinson may have turned to rape and murder to relieve stress. However, the psychiatrist added, if young offenders like Robinson received help in a controlled setting at an early age, they could improve.

On November 10, the jury sentenced Robinson to die by lethal injection. He showed no reaction, retaining the same blank expression he had worn throughout the trial. Six months later, when he was convicted of rape and the attempted murder of a five-year-old girl, fifty-seven years were added to his sentences, and forty more for his July 31 shoot-out with the police.

Legal Issues

Robinson decided that his trial attorneys had failed to tell him the importance of testifying on his own behalf, hurting his chance for a fair trial, so he wanted an opportunity to undo the error. He requested a hearing to challenge his convictions and sentences. However, Marinelli stated to reporters that during the trial, Robinson had refused to testify.

In November 1998, Robinson’s new attorney, Philip Lauer, challenged Robinson’s convictions at a postsentencing hearing, on the grounds that there were fundamental flaws in the trial procedures. Other issues involved racially biased jury selection, an error in allowing the three murders to be tried jointly, and an error in not changing the venue. On November 24, to the surprise of many, Robinson got his day in court.

Now twenty-three, Robinson testified in front of about thirty people, denying that he had committed the slayings and indicating that he regretted not proclaiming his innocence to the jury members who had convicted him. He testified for three hours, with five deputies in close proximity, casting blame on his former lawyers. At the time of his trial, he said, he’d given Marinelli and Burke the names of several people who could testify to his whereabouts when the three women were killed, as well as friends, coaches, teachers, and relatives who could attest to his character and accomplishments. Yet they called no alibi witnesses and presented few character witnesses. In addition, he continued, they did not inform him of the best strategy for defending himself and they did not use information about his childhood that might have helped him.

Robinson said he had declined to testify during his trial because he’d worried that prosecutors could have questioned him about his guilty plea to raping Denise Sam-Cali. “I was under the impression,” he stated, “that if I did testify then my past record was admissible.” He said he had not been informed otherwise.

Burke, one of Robinson’s former defense attorneys, also testified, disputing his claim about the defense strategy. He insisted that he and Marinelli had repeatedly encouraged Robinson to testify, both at his trial and at his sentencing. “I begged him,” Burke stated. While he could not dispute the fact that only a few witnesses from Robinson’s list had testified, he claimed that his and Marinelli’s choices at the time had been made in their client’s best interest. Many potential witnesses were contacted, he stated, but it was deemed that the testimony of some of them would be damaging to Robinson, while others refused to testify or could not be located because Robinson had given insufficient information about their whereabouts. Robinson mistrusted lawyers, even those working on his behalf, so he had been less than cooperative.

Robinson agreed, but said in his defense that he’d developed that mistrust during the Sam-Cali rape case, in which, he contended, his lawyer coerced him to plead guilty. He now regretted that decision.

The court deliberated over these revelations and decided that Robinson’s attorneys had acted in his best interests and had not been ineffective in their counsel, so he did not receive a new trial.

Two Down, One to Go

In June 2001, Judge Edward Reibman vacated Robinson’s death sentences in the murders of Burghardt and Schmoyer. In that trial, Reibman said, the instructions to the jury had not properly defined the aggravated circumstances of multiple murder. He allowed the defendant to have a new sentencing hearing.

More than four years later, in December 2005, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed the death sentence in the Fortney case and the first-degree murder convictions in the other two cases. The high court stated that although Robinson believed that his attorney had not presented mitigating circumstances on his behalf, the trial jury had indeed considered reasons against imposing the death penalty and had given him death anyway. The court similarly rejected Robinson’s claims that the prosecutor had improperly labeled him a predator (as well as his claim that the jury-pool selection system had been racially biased). Steinberg’s remarks during Robinson’s murder trial were found to be consistent with claims that Robinson had targeted a certain type of victim within a specific geographical area. So Robinson’s situation remained the same as it had been four years earlier—that is, until a legal development occurred the following year.

On March 1, 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that juveniles age seventeen and under were ineligible for the death penalty. This ruling affected Robinson’s conviction in the Burghardt murder, committed when he was seventeen. However, that death sentence had already been vacated. The Supreme Court’s decision simply meant that Lehigh County district attorney James Martin would not reopen that case, but he was nevertheless determined to seek a new hearing in the Schmoyer case.

Robinson’s death-penalty appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court had been denied in October 2005. In February 2006, Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell signed his death warrant, with an execution date set for April 4, 2006. This, too, was stayed by a federal appeal.

From prison in Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, Robinson posted on prisoner Web sites, looking for correspondents. He indicated that he enjoyed exercise, writing, music, and reading self-help books. He particularly liked, he wrote, to help others. “Life is so truly precious,” he wrote, “so anything I can do for another is something I’m interested in and like.” In August 2007, he requested a brain scan to test for a possible impairment in cognitive function that might have influenced his actions during the murders. A judge allowed it, and as of this writing, the results are pending.

For Brian Lewis, now retired, this case was one of the significant experiences of his career. He believes that he and his fellow officer were chosen for the risky assignment because they had proven themselves up to the task. “We were hard workers,” he said. “We were young, we were go-getters, and we loved the job.” He received a well-earned commendation for valor. “Looking back, it turned out good for everybody. I didn’t have to kill anyone and wrestle with that the rest of my life. I didn’t get hurt, no one else was hurt, and we caught him.”

Sources

“Allentown Man Guilty of Homicides.” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 1994.

“Allentown Murder Suspect Pleads Guilty in Separate Case.” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 2, 1994.

Alu, Mary Ellen. “A Survivor’s Story.” Morning Call, April 17, 1994.

Bucsko, Mike. “Juvenile Executions Ruling Affects Three.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 2, 2005.

Casler, Kristen. “Allentown Man Charged in Serial Murder, Rapes.” Morning Call, December 7, 1993.

_. “Experts Link Robinson to Crime Scene Evidence.” Morning Call, January 7, 1994.

_. “Allentown Crimes Fit Mold of Serial Killer.” Morning Call, December 8, 1993.

Devlin, Ron. “Killer Says Trial Flawed.” Morning Call, July 17, 1998.

Garlicki, Debbie. “Jurors’ Quest: What Makes Harvey Robinson Tick?” Morning Call, October 22, 1994.

_. “Jurors Choose Death for Robinson.” Morning Call, November 11, 1994.

_. “Trial Revealed Life of Robinson Victim.” Morning Call, November 11, 1994.

_. “Witnesses and Science Finger Robinson.” Morning Call, November 2, 1994.

_. “Robinson Gets 40 Years for Rape, Assault.” Morning Call, April 15, 1993.

_ . “Robinson’s Lawyers Seek Three Murder Trials.” Morning Call, July 26, 1993.

_. “Analyst Says Same Killer Took Three Lives.” Morning Call, July 27, 1993.

_. “Robinson Trial Clues Go Under Microscope.” Morning Call, October 29, 1994.

Grossman, Eliot. “Robinson Recalls Childhood, Insists He’s No Murderer.” Morning Call, November 25, 1998.

Rosen, Fred. “The Rapist Tried to Murder Her and She Knew He Would Try Again.” Cosmopolitan, March 1, 1996.

Petherick, Wayne. Serial Crime: Theoretical and Practical Issues in Behavioral Profiling. Oxford: Academic Press, 2006.

Todd, Susan. “Allentown Teenager Held in June Attack on Woman.” Morning Call, September 3, 1993.

Interview with Brian Lewis.