ELEVEN

JAMES B. GRINDER:

The Brain Never Lies

Around 2:45 a.m. on a Friday morning in 1984, the Missouri Highway State Patrol discovered Julianne Helton’s red-and-cream Citation abandoned at the Marceline junction in Macon County, Missouri. It was January 8, a cold day for a woman to have just walked away. Officers learned who owned the vehicle and made some calls. They found Julie’s parents, also living in Marceline, who told the officers their daughter had failed to return home from a party in New Cambria the evening before, and they had filed a report that she was missing. Calls to her acquaintances and people from the party turned up nothing. She had simply vanished.

Julie, a lifelong resident of Marceline and an employee of the Walsworth Publishing Company, was only twenty-five. Her parents could think of no reason that someone might want to hurt her. She was reliable, gregarious, and well liked at her job, and having grown up in the area, she had a large network of relatives. Every indication supported the frightening possibility that she’d met with foul play.

Damage to a water hose had caused her car to stall, but closer inspection showed a deliberate cut. This discovery threw a spotlight on men at the party who might have seen her and decided to be her “rescuer” when the car inevitably failed. Investigators sensed a setup. It seemed unlikely to have been a random incident, where a predator just happens along when a young woman needs help, but no known associate of Julie’s seemed a likely culprit. Since it was clear that the breakdown had been planned, it was also clear that someone had been watching her.

Dr. Lawrence Farwell, a neuropsychiatrist on the cutting edge of brain research. Brain Fingerprinting Laboratories Inc.

Investigators intensified their efforts to find her. She was last seen wearing a navy blazer, blue jeans, and a rose-colored sweater. The search party, armed with this knowledge, spread out around the area, covering more than a hundred square miles, in both Macon and Linn counties. They drove along roads that connected to where the car had stalled, and into wooded areas and farmland.

Three days later, on January 11, two volunteer searchers from the railroad company came across Julie’s fully clothed body. It lay in a snow-covered field near the Santa Fe railroad tracks, about eight miles northwest of where her car had stalled. The area was quickly sealed off and the body examined. Julie’s hands had been bound in front of her with baling twine and she’d been stabbed to death. There were two sets of footprints in the snow, the victim’s and prints of a size that implicated an adult male. This set led to and away from her body. A pool of blood had settled in the snow more than ten feet from the body, where weeds were smashed down, but no blood was found beneath the body. It appeared that Julie had died on the morning she disappeared. Her purse and the implement used to stab her were both missing.

An impromptu coroner’s jury was held at the site and these six people requested an autopsy. The frozen body was moved to the morgue, where the postmortem showed bruises and scrapes, as well as blunt-force trauma and deep stab wounds to the neck. Julie had also been raped. Her right hand showed defensive wounds, affirmed by broken fingernails, which suggested she had fought to save herself.

Julie’s family held a funeral service and the police continued to investigate. However, all they had were the footprints, which had probably changed from the time when they were left in the snow to the time when the body was found. A reward of $5,000 was offered for information. It would be the killer himself who would eventually supply this information.

The result of Grinder’s examination.

Brain Fingerprinting Laboratories Inc.

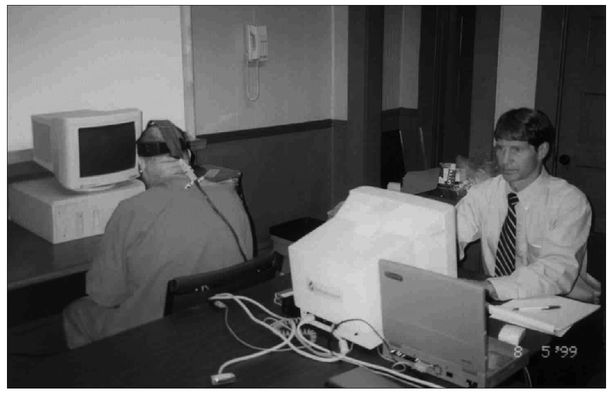

Farwell administering his brain scan test to suspected killer James Grinder. Brain Fingerprinting Laboratories Inc.

Foreshadow

Two years after this incident, a deer hunter walking down a remote, dead-end road came across skeletal remains near Brock Cemetery, thirty miles north of Russellville, Arkansas. He also found shreds of clothing and jewelry. The police called in a forensic anthropologist who said the bones appeared to belong to young adolescents. The likely candidates were Teresa Williams, Crystal Parton, and Cynthia Mabry, who had disappeared on December 2, 1976, a decade earlier, and were never heard from or found. Two were thirteen and one was fourteen.

The anthropological examination indicated with about 80 percent certainty that some of the bones matched Teresa and Crystal. There appeared to be only two sets of remains in this area. A thorough search around the cemetery and in the woods yielded nothing more, leaving Cynthia’s mother desperate to know what had happened to her daughter. She’d held out hope that the girl would one day come back.

At the time of the girls’ disappearance, the police had a key suspect. Teresa’s fourteen-year-old cousin told police he’d seen James B. Grinder, a local woodcutter, with Teresa that day. Grinder admitted he’d seen the girls hitchhiking and picked them up, but he’d dropped them off at the interstate exit for Pottsville. He gave them twenty dollars but claimed that was the last he saw of them. He returned home to his girlfriend. Since there was no evidence against him, he appeared to have an alibi, and since the girls were still missing, he was not charged. In fact, no one was charged, since two of the bodies were not found for over a decade and the third girl was still considered missing. Investigators had surmised that they were runaways.

Predator

More years passed and Grinder was arrested with two other men for burglary. The police questioned him about Julie Helton, offering him a deal for life in prison, so he confessed. He said he had planned the murder for about two months, watching and waiting. One night, he spotted her car parked at a business and punctured the radiator. Later that night, he saw her with her disabled car, the hood up, standing on an overpass—just what he’d been waiting for. He stopped to “assist,” and then two other men stopped as well—the men involved with him in the burglary. He said that Julie agreed to get into one man’s car, but they all ended up at a mobile home, three men and Julie. They used cocaine and then the men all raped her. Finally, they had to kill her to keep her from talking, so they took her to the railroad track, where Grinder stabbed her in the neck and in the mouth.

One of the problems with this confession was the testimony of the other two men, who claimed they had nothing to do with the rape or murder of Julie Helton. In fact, the physical evidence from the scene indicated that only one man had been with her when she died. Grinder then changed his story somewhat, adding the participation of a local police chief, and then recanted his confession altogether, saying that while he was present at the crime scene, he had not participated in either the rape or the murder. In addition, Grinder’s nephew confessed to the rape and, in exchange for immunity, corroborated one of Grinder’s statements.

The police chief, too, denied involvement, but he was subsequently suspended. The other two men remained in prison to await trial, although everyone knew that all the police had was Grinder’s confession, which was a mess. It would be a tough case to win, but they had to do something to get justice for the victim and her family.

When the Russellville police learned that James Grinder had confessed to a Missouri homicide, they decided to try to get more out of him about their missing-person case. Lieutenant Ray Caldwell and State Trooper Dwayne Lueter traveled to Macon County in 1998 to inform Grinder that two of the girls’ remains had been found. Grinder admitted to killing all three, providing details about physical evidence that had never been publicized, and clearing up the mystery.

He had picked up the three girls on December 2, 1976, he said, outside Russellville. They went with him to Morrilton, where he purchased alcohol. He then drove them to Brock Cemetery and raped Teresa and Crystal. Afterward, he strangled them and stabbed them in the neck. He hid their bodies under some brush. Cynthia was still alive, and he took her to another location in the woods and raped her. She, too, had to die, so he used a soda bottle to hit her over the head. When this failed to work, he picked up a tire iron and bludgeoned her several times. The place was so forlorn that he figured he did not have to hide her body, so he just left it there. A week later, he returned to the cemetery to pile more brush on the other two, still undiscovered.

Grinder’s former live-in girlfriend also admitted that he’d come in around midnight on that December 2 and told her that if anyone asked, she was to say he’d been with her all evening. He told her about the missing girls and gave her $200 to cover for him.

In 1998, David Gibbons, the Pope County prosecutor, filed one charge of capital murder against Grinder, which signified the premeditated killing of two or more people. However, the whereabouts of the remains of Cynthia Mabry plagued both the girl’s family and the investigators who had long been on the case. Even after twenty-three years, they wanted to find whatever they could and give the girl a proper burial. They hoped to bring Grinder to Arkansas so he could point out the exact location, but before they could do so, his situation in Missouri took some interesting new turns.

Try Something New

In early June 1999, Missouri attorney general Jay Nixon asked that first-degree murder charges be dropped against two of the men implicated in Grinder’s confession. Although it was initially believed that the semen samples removed from Julie had been used up in earlier testing, some turned up in a Colorado lab. DNA testing cleared the men and indicated that Grinder had lied when he described their involvement. Since Grinder had manipulated the evidence, Nixon stated that he would revoke the deal and reconsider the death penalty. Days later, after more testing, charges were also dropped against the police chief.

Sheriff Robert Dawson now faced a difficult situation. He had no physical evidence against Grinder, so the confession had been crucial. In 1993, court-ordered blood samples were taken, but the results were insufficient to support an indictment, especially for murder. Grinder had now changed his story so many times, even contradicting himself, that no one would have been surprised if he recanted altogether, which would have left Dawson with nothing. Given Grinder’s unreliability, they might have nothing even if he didn’t recant. After over ten thousand man-hours spent investigating the case and hoping for its resolution, the possibility that it could collapse alarmed everyone involved.

Dawson recalled recent news coverage of a neurological assessment technique called brain fingerprinting, a discovery of Dr. Lawrence Farwell, a neuropsychiatrist. With degrees from Harvard University and the University of Illinois, Farwell had been president and chief scientist of the Human Brain Research Laboratory since 1991. Along with brain fingerprinting, he had invented the Farwell Brain Communicator, a device that allowed a subject’s brain to communicate directly to a computer and speech synthesizer.

Farwell claimed that brain fingerprinting was 99.9 percent accurate. What Dawson had learned from the media coverage was that since the brain is central to all human activities, it records all experiences. This finding had many applications, including use in the criminal justice system. The act of committing a crime, as well as details from a crime scene, would be stored in the offender’s brain, which meant that the memory would have a measurable pattern.

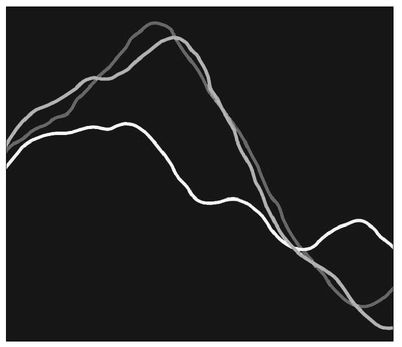

Brain fingerprinting records distinct patterns, called event-related potentials, which are measures of the brain’s electrical activity as it corresponds to events in the environment. By averaging the distinct patterns of electrical activity, a singular waveform arises that can be dissected into components related to cognitive functions. Those related to brain fingerprinting are the P300 and the MERMER. The P300 is a positive charge that peaks between 300 and 800 milliseconds in response to meaningful or noteworthy stimuli. Dr. Farwell found that the P300 was one aspect of a larger brain-wave response that peaks at 800 to 1,200 milliseconds after a response, which he called a MERMER (memory and encoding related multifaceted electroencephalographic response). If a suspect like Grinder was involved in a murder, for example, his brain activity when shown crime-relevant stimuli would produce a distinct spike on a graph. “Your brain says, ‘Aha! I recognize this,’ ” Farwell explained. Innocent people, he claimed, or people who had never been to the specific crime scene, would display no such neurological response.

Farwell utilizes three types of stimuli for testing a subject: target, probe, and irrelevant. Target stimuli are made “noteworthy” by exposing the subject to a list of words and phrases before any testing is done. When flashed on the screen, they should all elicit a recordable MERMER. Probes also contain noteworthy information, and this set is derived from details that investigators know about the crime and crime scene. This information is meaningful only to the actual perpetrator, and includes things done to the victim, where she was taken, how she was killed, items removed from her, and items left at the scene. The subject does not see this list until the test itself is performed. Irrelevant stimuli, to which no MERMER should occur, might include a different type of weapon, landscape, MO, or acts that were probably not done during the commission of the crime.

To strengthen the results, Farwell might test another angle. If the suspect offers an alibi for the time of the crime, a scenario can be devised from it and tested with the scanning device to see if the brain has a record of it. Thus the technology is useful in more ways than one. Like a fingerprint at a scene, it does not necessarily prove murder, but it adds an indicator of guilt. If a suspect had no good reason to be present at the scene, the MERMER becomes strongly suggestive evidence.

Other researchers have studied violence and the brain, testing reactions, impulsivity, and areas of neural processing, but Farwell had developed a patented headband equipped with EEG sensors to detect the brain’s response and chart it on a graph. Brain fingerprinting is an improvement over the polygraph machine, Farwell claims, in that it relies on neurological processes over which no one has control. Some people have managed to manipulate a polygraph, but they cannot fool his machine.

Farwell uses a specific protocol. First, details about the crime must be gathered by someone familiar with brain fingerprinting, just as fingerprints can only be properly lifted by a trained investigator. Then the subject responds to the material and the sets of responses are analyzed and compared; this is followed by what is called a statistical confidence reading, an evaluation of the reliability of the responses.

Dawson contacted Farwell to request that Grinder undergo the test, and the suspect agreed to participate. Farwell was happy to be involved. This would be a first for him. While he’d conducted field tests and lab experiments, including accurately distinguishing between a group of FBI agents and nonagents, he had not yet participated in an active criminal case. It was a good chance to prove his methods and device. Many who had heard of it assumed it was little more than a glorified lie-detector test, which would make the results potentially inadmissible in court. However, in the court of last resort, investigators on the Helton case were willing to try it.

Farwell brought his equipment to the Macon County Sheriff’s Office and prepared to test Grinder’s memory in the matter of the fifteen-year-old murder. Sheriff Dawson, Chief Deputy Charles Muldoon, and Randy King from the Missouri Highway Patrol, all of whom were involved in the investigation, provided the needed details for developing a case-specific test. Former FBI Supervisory Special Agent Drew Richardson assisted. He had been involved in earlier brain-fingerprinting experiments and had left the FBI to become a vice president of Farwell’s company. From all this information, Farwell created a series of phrases and images to be flashed at Grinder at timed intervals on a computer screen.

The following facts were noted in Farwell’s report. He followed the standard procedures, preparing to record the results for law enforcement. Before the test, Grinder was given a pretest in which details of the crime that he had already described were flashed on the computer. He was instructed to press a button when a certain type of “target” stimulus appeared, and to press a different button when something else appeared, which would include both probe stimuli and irrelevant information. If he was guilty, the probe stimuli should show the same response as the target stimuli.

The test itself was divided into blocks of twenty-four stimuli, each of which was presented three separate times. Grinder’s response to all of them was graphed and calculated in such a way that responses to “relevant” stimuli could be mathematically compared to his responses to “irrelevant” stimuli. Grinder participated in seven separate tests with five different sets of probes. He sat in a chair in front of the screen, wearing his orange prison jumpsuit and the sensor-equipped helmet that measured areas in the parietal, frontal, and central areas of his brain. If the test proved that Grinder was the perpetrator, and the testing was allowed into court (something that was not yet known), he faced a capital conviction, with a death sentence.

After forty-five minutes, the results seemed clear: the computer analysis showed “information present” for probe stimuli. The computed statistical confidence level was 99.9 percent accurate. There was no question about Grinder’s guilt: he had quite specific concealed knowledge about the crime. “What his brain said,” Farwell told reporters of the Fairfield Ledger, “was that he was guilty. He had critical detailed information only the killer would have. The murder of Julie Helton was stored fifteen years ago when he committed the murder.” As far as Farwell was concerned, he had proven his theory: the record of a crime can be stored indefinitely in the brain of the perpetrator, and technology can detect it, thus excluding other suspects. “We can use this technology to put serial killers in prison where they belong.”

Six days after submitting to brain fingerprinting, Grinder was in court to plead guilty. He was then taken to Arkansas to face a hearing. Sheriff Dawson acknowledged in a letter that the evidence provided by the test had been instrumental in obtaining the confession and guilty plea.

Arkansas authorities accompanied Grinder from Missouri so he could point out where he had murdered Cynthia. He showed them an area in the Ozark National Forest, but it was difficult to find anything so many years after the crime. For his guilty plea in Arkansas, he was sentenced to life in prison.

Brain Science

Clearly, brain fingerprinting is potentially revolutionary, although critics insist it needs more testing. Farwell has since been involved in other criminal cases, one with positive results for the future of the procedure, one without. In both cases, however, the procedure was not used in a jury trial but only during an appeal. At this writing, brain fingerprinting has yet to be allowed into court.

The issue of admissibility of new technologies purporting to be science is complex, dating back to 1923, when the District of Columbia Court of Appeals issued the first guidelines. In Frye v. United States, the defense counsel wanted to enter evidence about a device that measured the blood pressure of a person who was lying. The court had to scramble to figure out what to do, as there were no guidelines yet in place, and increasingly more attorneys were looking for scientific evidence to help convict or exonerate a defendant. The judge decided that the “thing” from which such testimony is deduced must be “sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.” In addition, the information offered had to be beyond the general knowledge of the jury.

This Frye standard became general practice in most courts for many years, vague though it was. Over the decades, critics claimed that it excluded theories that were unusual but nevertheless well supported. Each attempt to revise the Frye standard had its own problems.

In some jurisdictions now, including the federal courts, the Frye standard has been replaced by a standard cited in the Supreme Court’s 1993 decision in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., which emphasizes the trial judge’s responsibility as a gatekeeper. The court decided that scientific means grounded in the methods and procedures of science and knowledge is more reliable than gut instinct or subjective belief. The judge’s evaluation should focus on the methodology, not the conclusion, and on whether the evidence so deduced applies to the case. In other words, when scientific testimony is presented, judges have to determine whether the theory can be tested, the potential error rate is known, it was reviewed by peers, it had attracted widespread acceptance within a relevant scientific community, and the opinion was relevant to the issue in dispute.

Many attorneys look to these guidelines to distinguish between “junk science” and work performed with controls, scientific methodology, and appropriate precautions. But some guidelines are slippery, particularly when it comes to examining a suspect’s state of mind at the time of the crime. Subjective interpretations are the norm: a clinical practitioner uses a battery of objective assessments to examine the defendant’s background and activities just before the crime. The problem is that equally qualified practitioners can derive opposing conclusions from the same tests and observations, so state of mind at the time of the crime often comes down to whom the jury believes. There are certainly records of cases in which a defendant ably duped a practitioner about his ability to commit the crime in question. If Farwell’s invention can deliver on its promise, it could reduce reliance on subjective evaluation and perhaps increase the accuracy of assessments, at least as far as guilt is concerned.

“I have every reason to believe it will be viewed the same as DNA,” Farwell states. “We’re not reading minds, just detecting the presence or absence of specific information about a specific crime.” He believes that in the future, his device will dramatically alter the way suspects are interrogated. He views it as a way to reduce the number of false confessions and convictions that postconviction DNA testing has revealed over the past decade.

In November 2000, in an appeal for postconviction relief, an Iowa district court held an eight-hour hearing on the admissibility of this technology. The accused, imprisoned for twenty-two years, submitted to brain fingerprinting to try to prove he was innocent of committing a murder, and he passed. The MERM-ERS supported his alibi but not his participation in the crime. He then sought to have his conviction overturned, but the court said that the results of the test would not have affected the verdict. Yet, in the process, District Judge Timothy O’Grady ruled that the P300 theory met the Daubert Standard as admissible scientific evidence. But when the key witness heard about the test results, he admitted he’d lied in the original trial, so the convicted man appealed to the Iowa Supreme Court and was freed, based on a legal technicality and lack of evidence. While brain fingerprinting received a legal stamp of approval in this case, it has not yet been truly tested in the legal system.

As of early 2008, with more than 170 tests performed (80 of which were real-life situations as opposed to laboratory assessments), brain fingerprinting has proven reliable and accurate. There was not a single error with either information present or information absent. The CIA has given a generous grant for the work to continue. “I have high statistical confidence in it,” Farwell said.

One flaw, also relevant to the use of fingerprints, has been the inability of the test to distinguish between a person who was at a crime scene but did not commit the crime and one who was in the same place and is guilty.

Also, Farwell does not deal with memory research that demonstrates that memory is not a “storage tank” but an actively constructed process that can even result in false memories that are qualitatively as vivid as actual memories. More research must be done to accommodate issues such as age, substance abuse, stress, and memory disorders, all of which can affect the memory of a criminal. In addition, the subjective nature of the way investigators put together a case for test development—the basis for the probe stimuli—makes some scientists question its reliability.

In reports, Farwell says, “It is inevitable that the brain will take its rightful place as a central facet of criminal investigations.” While he’s probably correct in this prediction, there is still cause for concern. Brain fingerprinting might help to convict the guilty and exonerate the innocent, but its use might reinforce the use of other types of neurological testing that may appear to mitigate guilt. It could also force a reexamination of so many cases that this revolution could shake up the entire justice system. Whether we’re ready or not, scientific measurements, even ambiguous ones, will be proposed in future criminal cases.

My Brain Made Me Do It

Philosophers and many proponents of cognitive psychology hold that moral judgments are within our control, and thus people who choose to commit crimes, barring delusions, know what they are doing and that it is wrong. The legal system depends on this notion. However, recent research suggests that damage to an area of the brain just behind the eyes can transform the way people make moral decisions. The results indicate that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, implicated in the feeling of compassion, may be the foundation for moral regulations, assisting us in inhibiting (or not) harmful treatment of others. Failure in its development, or damage to it, might alter the way a person perceives the moral landscape, which will thus affect his or her actions. If juries include information of this kind in their deliberations, it could mitigate the harshness of the sentences they impose on convicted criminals. While more research must be done, other types of brain scans are being entered as evidence in the trials of some heinous crimes to show that the perpetrator could not help what he did.

Stephen Stanko kidnapped a young woman and served nearly a decade in prison for his crime. While he was incarcerated, he collaborated with two professors on a book about his experience. After his release, he got involved with a librarian, whom he later murdered before raping her teenage daughter. He also killed a seventy-four-year-old man, and went on the run, stopping here and there to socialize in bars. He was soon captured, already courting his next victim. Despite his vow to be a good citizen, he had proven only that he was a dangerous psychopath. That meant he lacked empathy for others, had a strong tendency toward self-interest, was able to charm and con others, and felt no remorse for his actions. He used people up for his own purposes and committed more crimes without inhibition.

During his trial, the prosecutor said Stanko was a man who lacked all remorse for his actions. He was a psychopath who knew what he was doing when he did it but felt no remorse afterward. The defense attorney, William Diggs, wanted to prove that Stanko had no control over his actions, the result of a brain defect, and was therefore insane. He hired Dr. Thomas H. Sachy, founder of Georgia Pain and Behavioral Medicine, to test Stanko. Sachy scanned Stanko’s brain with a PET-scan machine, and testified that it “showed decreased function in the medial orbital frontal lobes.” He explained to the jury that one region of the brain directly above the eyes and behind the eyebrows did not function normally, and “this [is the] area of the brain that essentially makes us human.”

Although the jury rejected Dr. Sachy’s notion and convicted Stanko, the age of neuro-imaging had arrived, and eventually defense experts will improve both their testing and their testimony until someone, somewhere, will convince a jury that psychopaths cannot help what they do any more than psychotic people can; both groups are mentally ill and both groups would be accorded equal freedom from criminal culpability.

Another effort to employ brain scans for deception detection comes out of Germany, from the Berlin Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience. As reported in 2007, people tested with MRI machines performed simple skills while scientists attempted to “read” their intentions before these intentions became actions. Because these machines can identify different types of brain activity and link them to certain brain states or behaviors, the scientists believed they could distinguish and accurately predict what a person would decide to do. Thus far, the accuracy rate on a small sample of subjects has been just over 70 percent—greater than chance. As the tests get more refined, that accuracy level is expected to improve.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, are also involved in making such predictions. Subjects were asked to make decisions about adding or subtracting numbers before the numbers were shown on a computer screen. Brain patterns indicated that these processes were different. Bursts of activity in the prefrontal cortex—“thought signatures”—helped researchers predict results. While the decision making was made on a simple level, which means the claims for this science must be limited, more disturbing possibilities are on the horizon. Scientists might one day be able to tell, without his or her consent, what a person is thinking or feeling. This may assist in criminal investigations, but it might also have unpleasant repercussion on other levels of society.

Our final case involves many areas of forensic science and psychology. Such coordinated teamwork is certainly the wave of the future. While a collective effort may take longer to find the truth than the use of a brain scan, especially when evidence and testimony are tenuous, such work can pay off.

Sources

Akin, David. “Brain Wave: A Test That Can Detect Whether Someone Has Seen Something Before Is Being Promoted as a Tool to Screen for Terrorists.” Globe and Mail, November 3, 2001.

Bell, Bill. “Brothers Charged in Murder are Released.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 8, 1999.

Carey, Benedict. “Brain Injury Said to Affect Moral Choices.” New York Times, March 22, 2007.

“Charges Dropped Against Third Man in Macon Murder Case.” Associated Press, September 4, 1999.

Dalby, Beth. “Brain Fingerprinting Testing Traps Serial Killer in Missouri.”

Fairfield Ledger, brainwavescience.com, retrieved January 5, 2007.

“DNA Evidence Doesn’t Support Case Against Two Men in 1984 Macon County Murder and Rape; Charges Dropped.” Attorney General’s News Release, June 7, 1999.

Farwell, Lawrence A. “Farwell Fingerprinting Testing.” Forensic Report prepared for Sheriff Robert Dawson, August 5, 1999.

Feder, Barnaby. “Truth and Justice, by the Blip of a Brain Wave.” New York Times, October 9, 2001.

“Federal Agency Views on the Potential Application of Brain Fingerprinting.” Investigative Techniques, October 2001.

“German Scientists Reading Minds Using Brain-Scan Machines.” Associated Press, March 6, 2007.

Gross, Thom. “Rural Town Suspends Police Chief.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 27, 1993.

“Helton Case Still Open.” Chronicle Herald, January 10, 1984.

Krushelnycky, Askold. “Brain Fingerprinting Proves Death Row Convict’s Innocence.” London Independent, July 18, 2004.

“Man Gets Life Without Parole After Guilty Plea in 1976 Slaying.” Associated Press, September 8, 1999.

McKie, Robin. “It’s the Thought that Counts for the Guilty.” The Observer, April 25, 2004.

Meisel, Jay. “Killer’s Confession to Let Mom Bury Daughter at Last.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 8, 1999.

_. “Man Points to Location of Girl Killed 23 Years Ago.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 17, 1999.

_. “Man, 55, is Charged in ’76 Deaths of Three Girls.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 6, 1998.

“Murder on His Mind.” CBS 48 Hours, January 13, 2007.

Obituary for Julianne Helton. Chronicle Herald, January 13, 1984.

Paulson, Tom. “Brain Fingerprinting Touted as Truth Meter.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 1, 2004.

Sloca, Paul. “Nixon Asks That Charges be Dropped against Murder Suspects in Macon Case.” Associated Press, June 7, 1999.