The rehabilitation of

Louie Zamperini began with a key.

It was 1931, and Louie was fourteen. While in a locksmith’s shop, he heard someone say if you put any key in any lock, it has a one in fifty chance of fitting. Inspired, he began collecting keys and trying locks. He had no luck until he tried his house key on the back door of the Torrance

High gym. When basketball season began, no one understood why the stands were full when so few tickets had been sold. Finally, someone discovered Louie sneaking kids in the back door. Louie was hauled to the principal, who punished him by barring him from athletic and social activities. Louie, who never joined anything, was indifferent.

Pete headed straight to the principal. Louie craved attention, Pete told him, but had never won it in the form of praise, so he sought it in the form of punishment. If Louie was recognized for doing something right, he’d turn his life around. Pete asked the principal to let Louie join a sport. When the principal refused, Pete asked if he could live with allowing Louie to fail. It was a cheeky thing for a boy to say to his principal, but Pete was the one kid who could get away with such a remark. The principal gave in.

Pete had big plans for Louie. A senior in 1931–32, Pete was a track star,

having set the school’s mile record of 5:06. Watching Louie, whose getaway speed was his saving grace, Pete thought he saw the same talent. He wanted to make a runner out of him.

In the end, it wasn’t

Pete who got Louie onto a track. It was Louie’s weakness for girls. In February, some girls began assembling a team for an interclass track meet, and long-legged Louie looked like he could run. The girls worked their charms, and Louie found himself on the track, barefoot. When everyone ran, he followed, churning along with jimmying elbows. As he labored home last, he heard tittering. Gasping and humiliated, he ran straight off the track and hid under the bleachers. The coach muttered that that kid belonged anywhere but in a footrace.

From then on, Pete was all over Louie, herding him out to train and riding his bike behind him, whacking him with a stick. Resentful, Louie dragged his feet, bellyached, and quit. Pete made him keep going. He entered Louie in races, and Louie started winning.

Pete was right about Louie’s talent, but being forced to run made Louie defiant. At night he listened to the train whistles, and one day in the summer of 1932, he couldn’t bear it any longer.

It began over a chore Louie’s father asked him to do. Louie resisted, a spat ensued, and Louie threw clothes into a bag and stormed toward the front door. His parents ordered him to stay; Louie was beyond persuasion. As he walked out, his mother rushed to the kitchen and emerged with a sandwich. Louie stuffed it in his bag and left. He was on the front walk when he heard his name called. When he turned, there was his father, grim-faced, two dollars in his outstretched hand. It was a lot of money for a man whose pay didn’t last the week. Feeling a swell of guilt, Louie took it and walked away.

He rounded up a friend, and together they hitchhiked to Los Angeles, broke into a car, and slept on the seats. The next day, they jumped a train, climbed onto the roof, and rode north.

The trip was a nightmare. The boys got locked in a boxcar so hot they were frantic to escape. Louie found a metal bar, climbed on his friend’s

shoulders, pried open a roof vent, squirmed out, and helped his friend through. Then they were discovered by the railroad detective, who forced them to jump from the moving train at gunpoint. For several days, they walked. One night as they sat in a rail yard, filthy, sunburned, shivering, and wet, sharing a stolen can of beans, Louie remembered the money in his father’s hand, the fear in his mother’s eyes as she gave him a sandwich. He stood up and headed home.

When Louie came in the door, Louise threw her arms around him, led him to the kitchen, and gave him a cookie. Anthony came home, saw Louie, and sank into a chair, his face soft with relief. Louie went upstairs, dropped into bed, and whispered his surrender to Pete. He was going to be a runner, and he was going to go all out.

In the summer of 1932, Louie did almost nothing but run. On a friend’s invitation, he went to a cabin in California’s high desert. Each morning, he rose with the sun, picked up his rifle, and jogged into the sagebrush. He ran over hills, over the desert, through gullies. He chased bands of horses, trying in vain to snatch a fistful of mane and swing aboard. On his run back each afternoon, he shot a rabbit for supper. In the morning he rose to run again. For the first time in his life, he wasn’t running from something or to something, not for anyone or in spite of anyone; he ran because it was what his body wished to do. All he felt was peace.

He came home with a mania for running. On Pete’s orders, he ran everywhere. He ran his entire paper route for the Torrance Herald, to and from school, and to the beach and back, veering onto neighbors’ lawns to hurdle bushes. He gave up drinking and smoking. To expand his lung capacity, he ran to a public pool, dove to the bottom, grabbed the drain plug, and floated there, hanging on a little longer each time. Eventually, he could stay underwater for three minutes and forty-five seconds. People kept jumping in to save him.

He also found a role model. Track was hugely popular, and its elite performers were household names. Among them was Kansas University miler

Glenn Cunningham. As a boy, Cunningham was in a schoolhouse explosion,

and his lower body was burned so badly that a month and a half passed before he could sit up. Once he could stand, he pushed himself about by leaning on a chair, his legs floundering. Eventually, hanging off the tail of a horse named Paint, he began to run, a gait that initially caused him excruciating pain. In a few years, he was racing, obliterating his opponents by the length of a homestretch. By 1932, he was a national sensation, soon to be acclaimed the greatest miler in American history. Louie had his hero.

In the fall of 1932, Pete entered Compton, a tuition-free junior college, where he became a star runner. In the afternoons, he commuted home to coach Louie, perfecting his stride and teaching him strategy. Pete thought the sprints Louie had been running were too short. He’d be a miler, just like Cunningham.

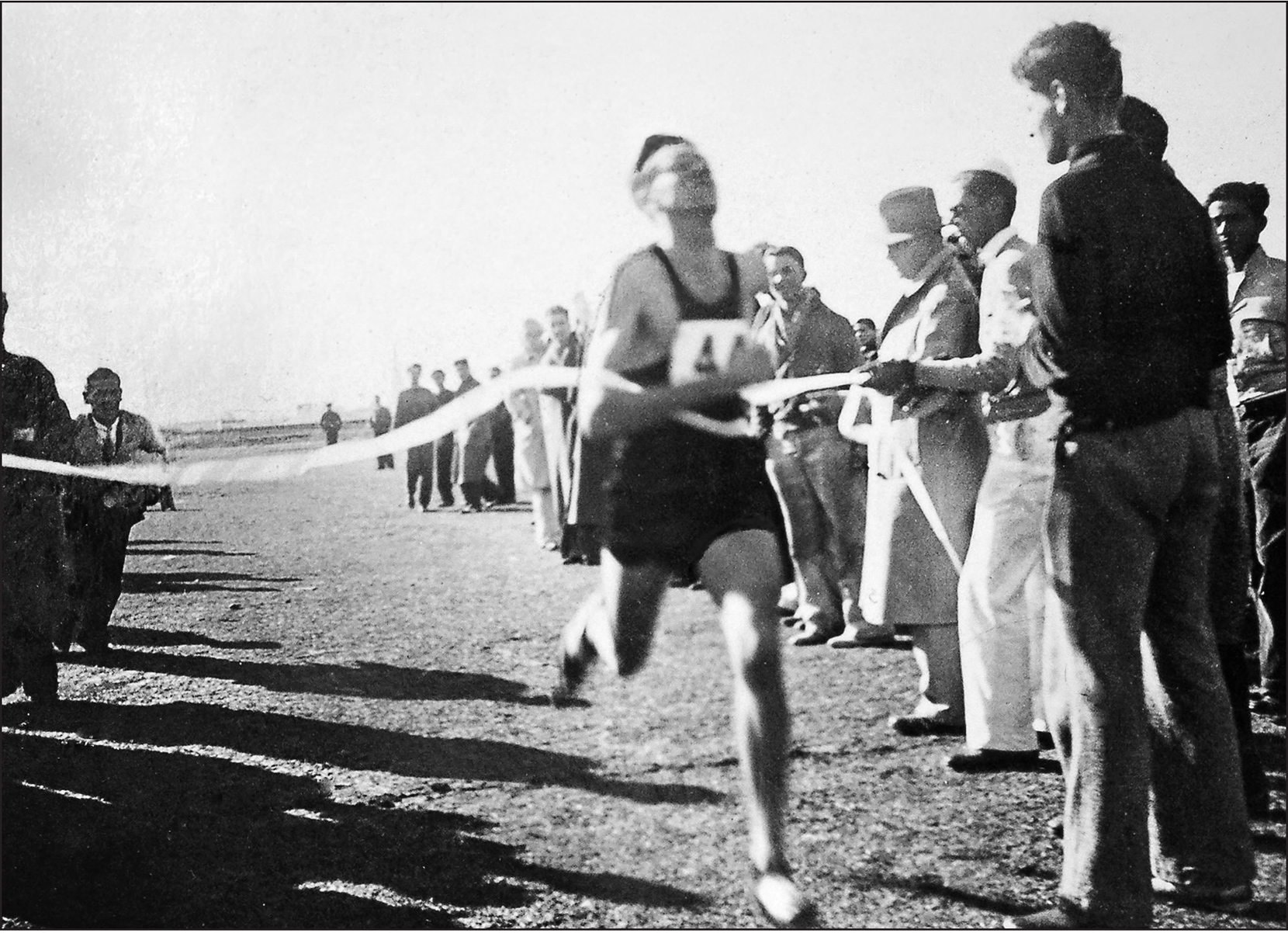

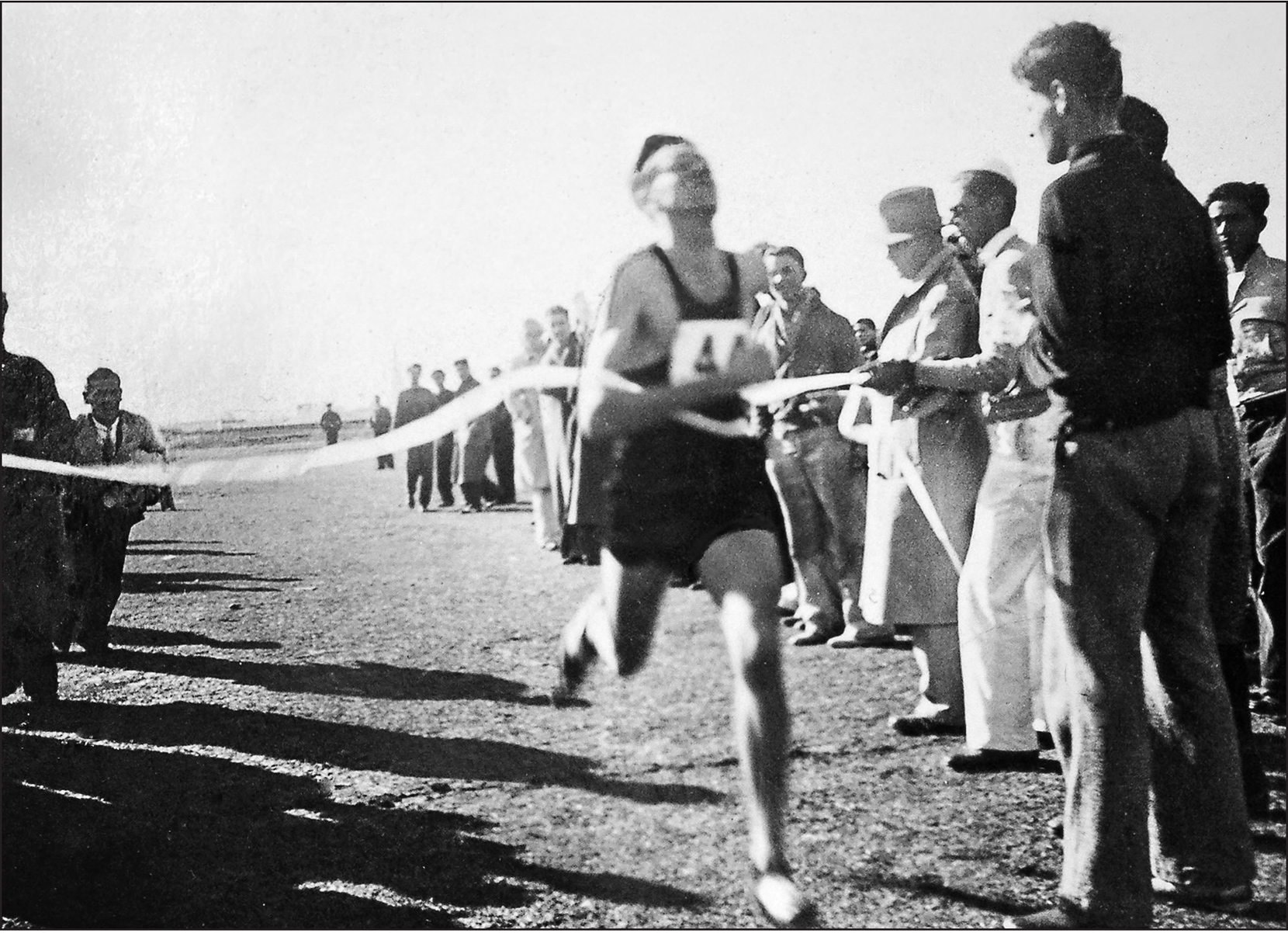

In California, winter-born kids started new grades in January. In the first days of 1933, just before he turned sixteen, Louie began tenth grade. When the track season began, he set out to see what training had done for him. Competing in black silk shorts that his mother had made from a skirt, he won an 880-yard race, breaking the

school record, co-held by Pete, by more

than two seconds. A week later, he ran a field of milers off their feet, stopping the watches in 5:03, three seconds faster than

Pete’s record. Week after week, he kept winning, and getting faster. By late April, his mile time was down to 4:42. “Boy! oh boy! oh boy!” read a local paper. “Can that guy fly? Yes, this means that Zamperini guy!”

Louie streaked through the season unbeaten and untested. When he ran out of high schoolers to whip, he took on Pete and thirteen other college runners in a two-mile race at Compton. Though he’d never even trained at the distance, he won by fifty yards. Next he tried the two-mile in

UCLA’s Southern California Cross-Country meet. Running so effortlessly he couldn’t feel

his feet touching the ground, he took the early lead and kept pulling away. At the halfway point, he was an eighth of a mile ahead, and observers began speculating on when the boy in the black shorts would collapse. Louie didn’t collapse. After he flew past the finish, rewriting the course record, he looked back. None of the other runners was even in sight. Louie had won by more than a quarter of a mile.

He felt as if he would faint, but it wasn’t from exertion. It was from the realization of what he was.