Oahu was still ringing from the

Pearl Harbor attack. The roads were pocked with

bomb craters. The island was on constant alert for attack or invasion, and so camouflaged, a serviceman wrote, “one sees only about 1/3 of what is actually there.” At night, it disappeared; every window had lightproof curtains, every car had covered headlights, and blackout patrols forbade even the striking of a match. Servicemen wore gas masks in hip holsters. Surfers had to worm under barbed wire running along Waikiki Beach.

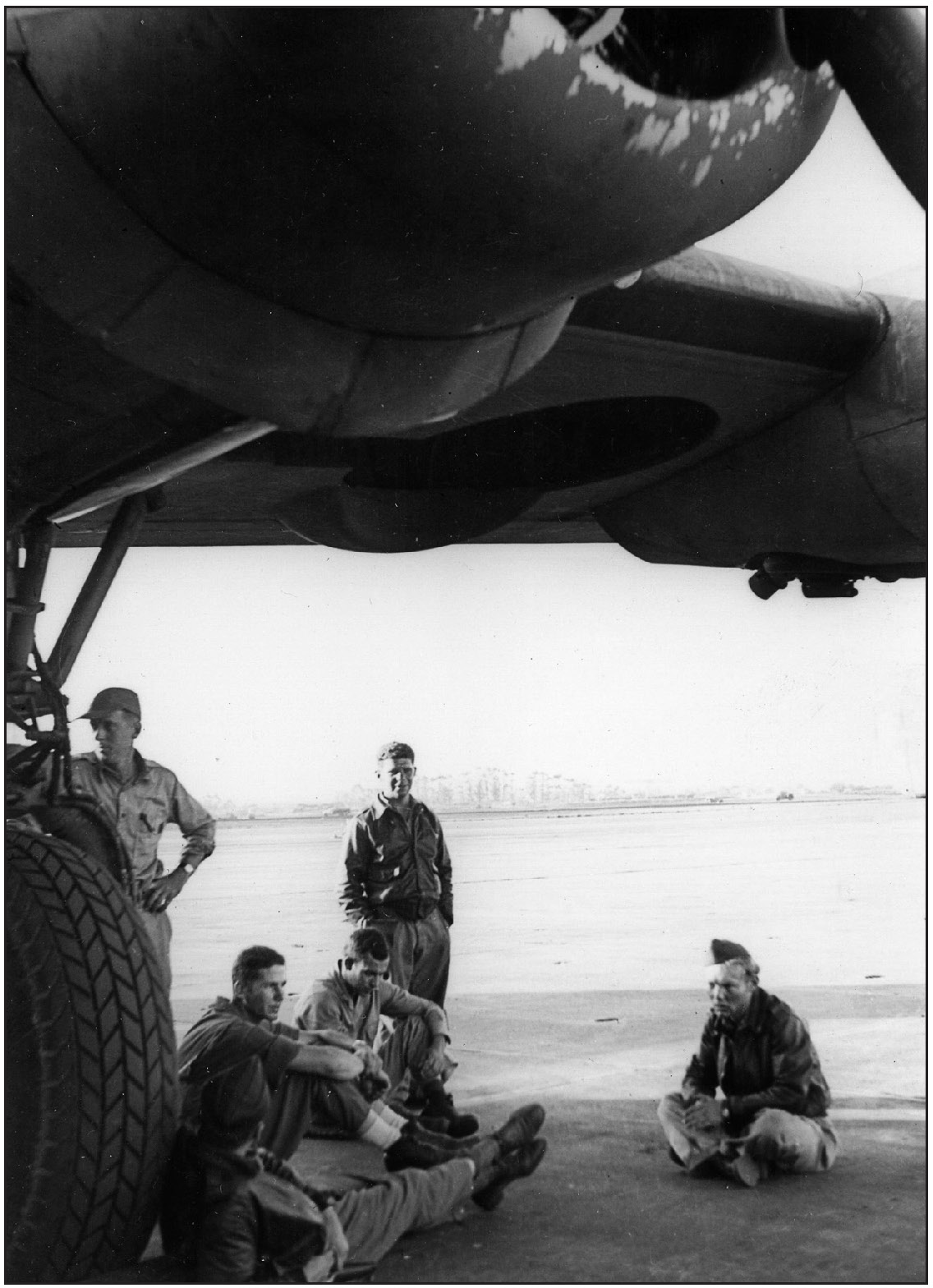

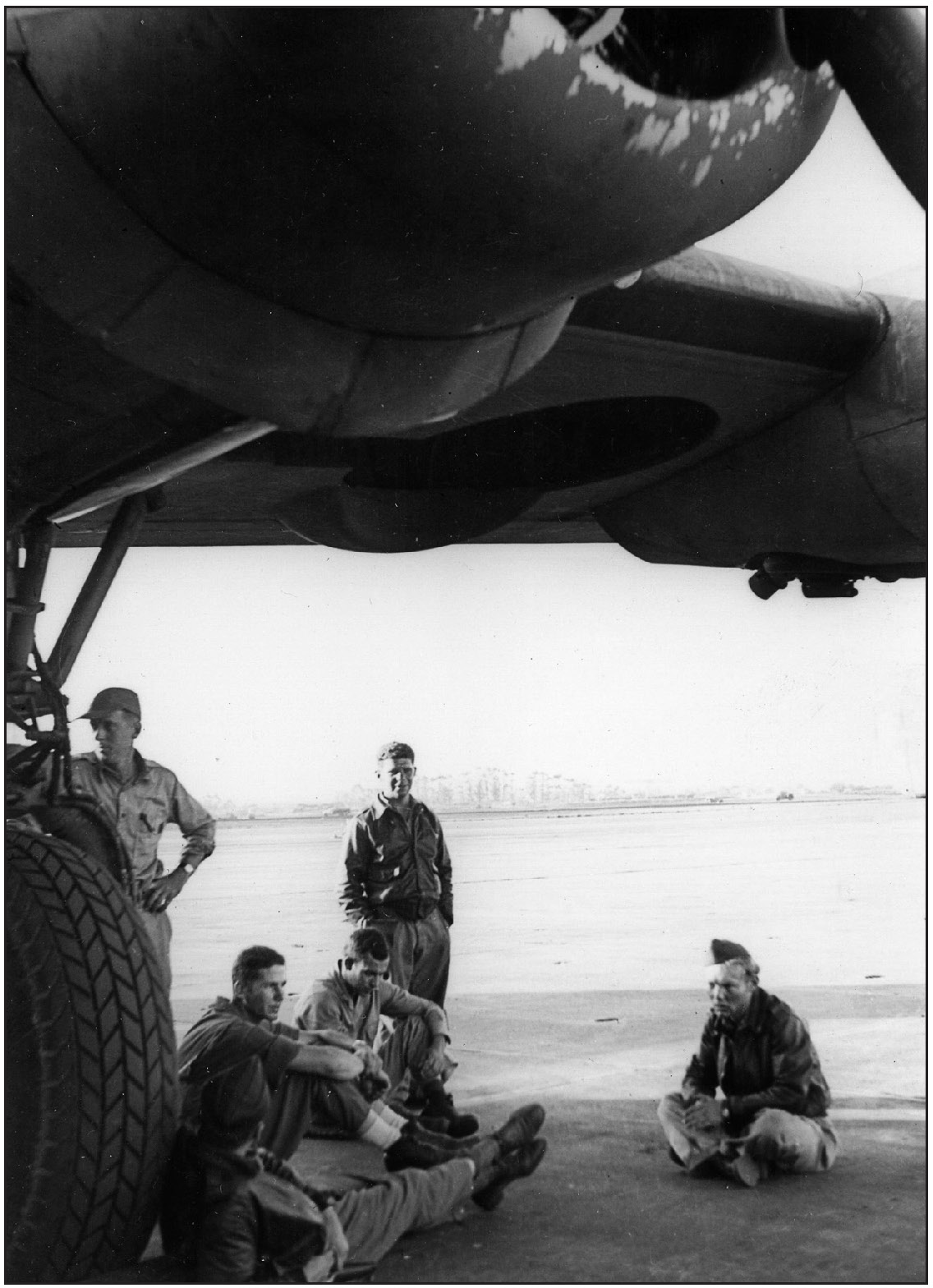

At Kahuku air

base on Oahu’s north shore, Louie and Phil were assigned to a barracks with

Mitchell,

Moznette, twelve other officers, and hordes of mosquitoes. “You kill one,” Phil wrote, “and ten more come to the funeral.” The barracks, Phil added, looked “like a dozen dirty Missouri pigs have been wallowing on it.” The nonstop revelry didn’t help. One night, as Louie and Phil wrestled over a beer, they plowed down three wall partitions. When

William Matheny, their colonel, saw the wreckage, he grumbled that Zamperini must have been involved.

Everyone was eager to fight, but there was no combat. In its place was “sea search”—dull daylong ocean flying

patrols overseen by a lieutenant everyone

hated. A nitpicker and rank-puller, he was loathed thanks to an incident in which one of

Super Man’s engines quit in midflight. When Phil returned the plane to base, the furious lieutenant ordered them back up. When Louie offered to fly on three engines if the lieutenant joined them, the lieutenant abruptly changed his mind.

The tedium of sea search made practical joking irresistible. When a ground officer griped about airmen’s higher pay, the crew invited him to fly the plane. They sat him in the copilot’s seat while Louie hid under the navigator’s table, by the yoke control chains. When the officer took the yoke, Louie tugged the chains, making the plane swoop up and down. The officer panicked, Louie smothered laughter, and Phil kept a poker face. The officer quit carping about airmen’s pay.

Louie’s two most notorious pranks involved Phil, chewing gum, and their new copilot, a massive ex–football player named Charleton

Cuppernell, who replaced Moznette when the latter joined another crew. In the first incident, after Cuppernell and Phil swiped his beer, Louie retaliated by jamming gum

into the cockpit urine relief tube. On the next flight, the call of nature was followed by an inexplicably brimming urine tube, turbulence, and at least one wet airman. Louie hid in Honolulu to escape punishment.

On another occasion, to get even with Cuppernell and Phil for stealing his gum, Louie replaced it with a laxative variety. Just before a long flight, Cuppernell and Phil each stole three pieces, triple the standard dose. As Super Man flew, pilot and copilot, in great distress, made alternating dashes to the back of the plane, yelling for someone to get a toilet bag. When the bags were used up, Cuppernell dropped his pants and hung his enormous rear out the window while four crewmen clung to him to keep him from falling out. When the ground crews saw the results on the plane’s tail, they were furious. “It was like an abstract painting,” Louie said.

Phil’s boredom remedy was hotdogging. Returning from sea search, he’d buzz Oahu so low he could look straight into the first-floor windows of buildings. It was, he said, “kind of daring.”

On their days off, the crew played poker and divvied up Cecy’s care

packages, and Louie and Phil tooled around in borrowed cars. Along the way, they came upon several airfields, and were amazed to discover that all the planes and equipment were made of plywood, an elaborate ruse to fool Japanese flying reconnaissance. One day, this information would be very important.

Paradise was the officers’ club, where there was beer and pretty girls with ten-thirty curfews. When the crew got the squadron’s best gunnery scores, Louie pinned officers’ insignia to the enlisted men’s uniforms and snuck them in. Just after Louie rose to dance with a girl, Colonel

Matheny sat down in his place and began talking to the terrified Clarence Douglas, who was pretending to be a second lieutenant. When Louie ran to Douglas’s rescue, the unsuspecting colonel got up and told him what a fine man Douglas was.

On the dance floor, Louie spotted the hated lieutenant who’d ordered them to fly on three engines. He found a bag of flour, recruited a girl, and began dancing near the lieutenant, dropping flour down his collar with each pass. After an hour, the whole club was watching. Louie snagged a glass of

water, danced up behind his victim, dumped the water down his shirt, and took off. The lieutenant spun around, his back running with dough. Unable to find the culprit, he stormed out.

Just before Christmas, the crew’s hour finally came. Ordered to fly to

Midway Island, they were greeted with a case of Budweiser and big news. The Japanese had built a base on

Wake

Atoll. In the

Pacific War’s biggest raid yet, America was going to burn it down. It would be a sixteen-hour mission, nonstop, pushing the B-24s as far as they could go. Even with auxiliary fuel tanks, they’d be cutting it extremely close.

On December 23, 1942,

twenty-six B-24s lifted off of the Midway runway.

Super Man slipped toward the rear. The planes flew through the afternoon and into night.

At eleven p.m., Phil switched off the outside lights. Clouds closed in.

Wake was very close now, but they couldn’t see it. In the greenhouse, Louie felt a buzzing in himself, the same sensation he’d felt before races. Ahead, Wake slept.

At midnight, Colonel

Matheny, piloting the lead plane, broke radio silence.

“This is it, boys.”

Matheny sent his bomber plunging out of the clouds, and there was Wake. He barreled toward a string of buildings, hauled the plane’s nose up, and yelled to the bombardier.

“When are you going to turn loose those incendiaries?”

“Gone, sir!”

At that instant, the buildings exploded. Behind Matheny, wave after wave of B-24s dove at Wake. The Japanese ran for their guns.

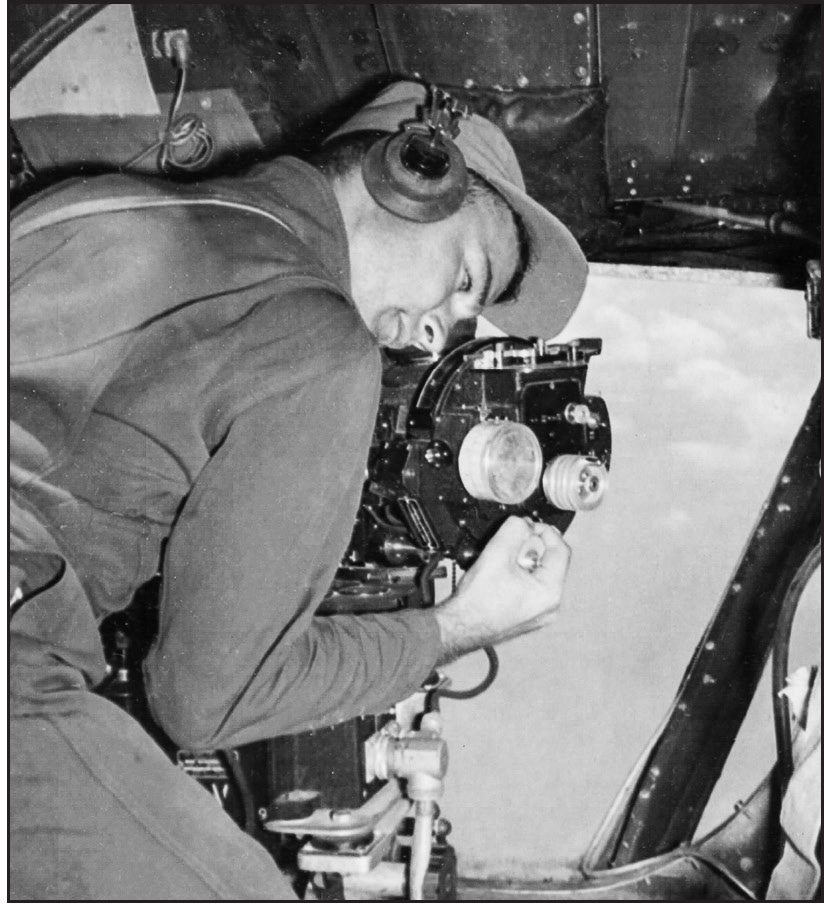

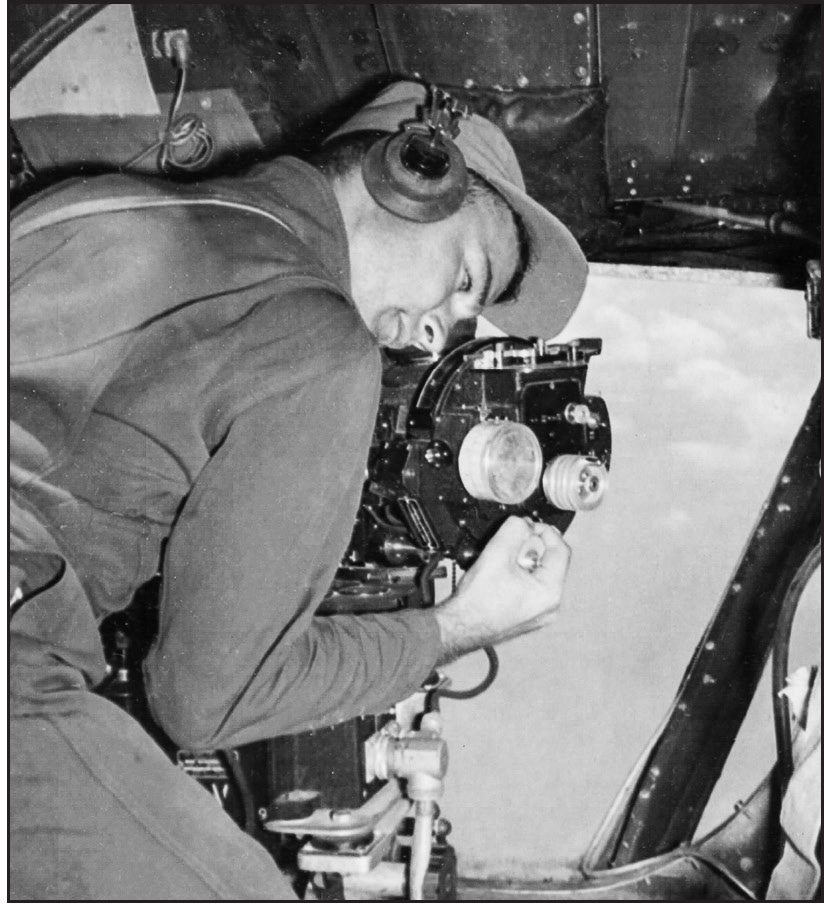

In Super Man, well behind and above the leading planes, Louie saw throbs of light in the clouds. As Phil began the plane’s dive, Louie opened the bomb bay doors, flipped his bomb switches, and fixed the settings. The orders were to dive to four thousand feet, but when the plane reached that altitude, it was still in clouds. Louie’s target was the airstrip, but he couldn’t see it. Phil pushed the plane lower, moving at terrific speed. At 2,500 feet, Super Man speared through the clouds and Wake stretched out, sudden and brilliant, beneath it.

The islands were a blaze of garish light. Everywhere, bombs were striking targets in mushrooms of fire. Searchlights swung about, their beams reflecting off the clouds and back onto the ground, illuminating scores of Japanese in their sleeping clothes, sprinting in confusion.

To Pillsbury, “every gun in the world” seemed to be firing skyward. Antiaircraft guns lobbed shells over the planes, where they erupted, sending shrapnel showering down. Tracer bullets, emitting color to allow gunners to see where

they were firing, streaked the air in yellow, red, and green. Watching the clamor of colors, Pillsbury thought of Christmas. Then he remembered: they’d crossed the international date line and passed midnight. It

was Christmas.

Phil wrestled

Super Man out of its dive. Louie spotted the taillight of a Japanese Zero fighter plane rolling down the runway. He aimed for it. Very

close, something exploded, and

Super Man rocked. A shell burst by the left wing, another by the tail. Louie loosed a bomb over the Zero, then dropped his five other bombs over bunkers and parked planes.

Relieved of three thousand pounds of bombs,

Super Man bobbed upward. Louie yelled “Bombs away!” and Phil rolled the plane left, through streams of

antiaircraft fire. Louie looked down. His bombs landed in splashes of fire on the bunkers and planes. He missed the Zero but had bull’s-eyed the runway. Phil turned

Super Man back for Midway. Wake was a sea of fire and running men.

As

Super Man flew for home, Louie realized they had a major problem. The bomb bay doors were stuck open. He climbed back and looked. When

Phil had wrenched the plane out of its dive, the auxiliary fuel tanks had slid into the doors. Nothing could be done. With the open bomb bay dragging against the air,

Super Man would burn right through its fuel. Given that this mission was stretching the plane’s range to the limit, it was sobering news.

They could do nothing but wait. They passed around pineapple juice and sandwiches. Drained, Louie stared at the sky, watching the stars through breaks in the clouds.

Seventy-five miles away from Wake, one of the men looked back. He could see the island burning.

As day broke, a general stood by the

Midway airstrip, waiting for his bombers, his face furrowed. Fog hung low over the ocean, spilling rain. For the pilots, finding tiny Midway would be difficult, and there was the question of whether their fuel would last long enough.

One plane appeared, then another and another. One by one, they landed, all critically low on fuel. Super Man wasn’t in sight.

Out in the fog, Phil must have looked at his fuel gauge and known he was in trouble. With his bomb bay open and wind howling through the fuselage, he’d dragged away his fuel. He didn’t know if he’d find Midway, and didn’t have enough fuel to fly around searching for it. At last, he spotted the island. At that moment, one of Super Man’s engines sputtered and died.

Phil nursed the plane along, aiming for the runway. The remaining engines kept turning. At touchdown, a second engine died. Moments later, the other two engines quit. Had the route been only slightly longer, Super Man would have hit the ocean. The general came running, smiling. Every plane had made it back.

News of the raid broke, and the airmen were given medals and lauded as heroes. In the Honolulu Advertiser, Louie found a cartoon depicting his role in bombing Wake. He clipped it out and tucked it in his wallet.

The men felt cocky. An admiral said Japan might be finished within a year. Phil heard men talking about going home.

“Methinks,” he wrote to his mother, “it’s a little premature.”