Fathers and Sons: Ollie – War and Peace

The town of Harlem, Georgia, lies on the old cross-country route that runs from Georgia’s second city of Augusta to its capital, Atlanta, though today the road peters out at Covington and joins the interstate highway. The railway track runs across the main street, and houses with neat lawns line the few roads that meander about the flat, green, pleasant countryside. The local histories relate that the town itself was founded by one Newman Hicks, who resigned from the railroad when required to work on Sunday and vowed to build a town of his own where no hard liquor would be sold. The name of Harlem was chosen deliberately to reflect the then fashionable – and very white – New York suburb of that name.

Today, it is still a quiet haven, akin in some ways to the mythical Scottish town of the musical Brigadoon, in that it seems to slumber through most of the year and then come alive in a sudden burst of dynamism for one day a year, the first Saturday of October, to celebrate the annual Oliver Hardy Festival.

The first sight of Harlem from the road tells you all you need to know – emblazoned on the white water tower, the smiling face of Our Hero and the legend:

HARLEM – BIRTHPLACE OF OLIVER HARDY

As you slow down for the traffic lights at the turn into Main Street a great multi-coloured mural on the side of a brick wall greets you: Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy wearing their signature bowler hats, and beside that a smaller picture of the duo leaning against the grand-piano crate as seen in their classic movie short, The Music Box.

A memorial plaque, marked as a ‘Georgia Historic Marker’, is set up outside the police station. It proclaims the official tale:

OLIVER NORVELL HARDY

HARLEM BECAME THE BIRTHPLACE OF ONE OF HOLLYWOOD’S GREATEST COMEDY TEAMS WHEN OLIVER HARDY WAS BORN JANUARY 18, 1892. AFTER HIS FATHER DIED AND WAS BURIED IN

THE HARLEM CEMETERY THE YEAR OF OLIVER’S BIRTH, MRS HARDY TOOK THE FAMILY TO MILLEDGEVILLE WHERE SHE BECAME THE MANAGER OF THE BALDWIN HOTEL. YOUNG OLIVER WAS ENTHRALLED BY THE VISITING TROUPES OF PERFORMERS WHO STAYED THERE. LATER, AS MANAGER OF THE TOWN’S FIRST MOVIE THEATRE, HARDY PERFORMED REGULARLY.

AFTER ATTENDING GEORGIA MILITARY ACADEMY, THE ATLANTA CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC, AND, FOR A SHORT TIME, THE UNIV. OF GEORGIA, HARDY LEFT GEORGIA IN 1913 FOR THE NEWLY ESTABLISHED FILM COLONY IN JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA. AFTER WORKING AT VARIOUS STUDIOS ON THE EAST COAST, HE LEFT FOR HOLLYWOOD IN 1918.

When the legend becomes truth, print the legend. In fact, Harlem is a little embarrassed that the house Ollie was said to have been born in was one of the few in the area to be torn down completely, some decades ago, and replaced with the local automatic laundry. At 125 South Hicks Street, it proudly proclaims –

OLLIE’S LAUNDRY, BIRTHPLACE OF OLIVER HARDY

- and boasts (let no one say your author stints on his research) three commercial washing machines, thirty-five regular washing machines, and four driers.

I attended the festival day of 2 October 1999, getting lost in the unexpectedly vast crowds that descended on the place on a fine sunny day. Twenty thousand people had visited the festival the year before, and this year the figure was closer to thirty thousand. There was a regular old-time small-town American parade: vintage cars, the fire brigade, Georgia cadets, majorettes, stilt-walkers, the Civil War re-enacters, Boy Scout Pack 105, Evans High School ROTC, Thomson Shriners, school bands, clowns, the mayor on a float with Santa Claus, the works. The Stan and Ollie professional lookalikes – Messrs Dale Walter and Dennis Moriarty, two merry gentlemen of Ohio – were on hand to entertain the children, as well as a strong contingent from an assortment of tents of the ‘Sons of the Desert’. Then there were craft booths, Laurel and Hardy T-shirts, non-stop movies in the police station’s conference room, memorabilia displayed at the City Hall, the lookalike competition, the Miss Oliver Hardy Scholarship Pageant, Grovetown Elementary Jumping Jaguars, Country Kickers, Master City Cloggers and Square Dancers, G. R. Dean Gospel Choir and the chicken barbecue held in the local fire station, with generous portions piled on paper plates.

Ollie would certainly have been tickled pink. It was his kind of South that was being celebrated – open-hearted, fun-loving, friendly, with a warm welcome for strangers who came from far and wide to honour the Favourite Son. It was an inclusive crowd, black and white – if predominantly white – comfortable in its present prosperity in a buoyant state that not long ago gave a progressive, if short-lived, president, Jimmy Carter, to the US of A.

But the stronger the sunshine, the deeper the shadows. This was not always a happy place …

Standing in the Harlem graveyard, among green lawns, and good brown earth. In a neat plot, with fresh-laid gravel, there are urns of flowers beside two tombstones. The inscription on the stones is faint, and only just readable:

OLIVER HARDY

BORN DECEMBER 5 1844

DIED NOVEMBER 22 1892

DIED NOVEMBER 22 1892

And beside him:

CORNELIA E. MAGRUDER

1846 – 1888

In 1861, before Harlem town was founded, the lands west of Augusta were farming lands, mainly plantations. The Confederate States had declared their independence in February, and in April a Confederate Army had fired on Fort Sumter. President Lincoln called for volunteers for the Union. All over the South, volunteer companies were being formed. In Columbia County in Georgia, Company K, the ‘Ramsey’ volunteers, was set up by Captain Joshua Boyd from planters and their sons, farmers, plantation overseers, a number of goldminers and sawyers. It was to be part of the Sixteenth Georgia Regiment. A memorial book, compiled by Thomas Earl Holley, of Thomson, Georgia, from contemporary records, lists the following:

Captain Joshua Boyd

Second Lieutenant George Ramsey Magruder

Third Sargent Edwin C. Magruder

Fourth Sargent Oliver Hardy

Second Lieutenant George Ramsey Magruder

Third Sargent Edwin C. Magruder

Fourth Sargent Oliver Hardy

Thirteen further officers, one surgeon, and eighty-seven soldiers are listed. When recruited, Oliver Hardy joined as a private. He was seventeen years old. He was the son of Catherine and Samuel Hardy, a planter, the third of eight children. The Hardys were of English stock, but established in Georgia. Researcher Leo Brooks has traced the Hardy family tree back to Jesse Hardy, a soldier who accompanied the founder of the Colony of Georgia, General James Oglethorpe, from the Old to the New World, in 1733, claiming lands for King George II. One of his sons, John Hardy, was a captain in the Revolutionary War and received bounty land for his services, in Warren and Columbia Counties, in the 1780s. His son, also John, begat Samuel Hardy, who, in 1840, was listed as owning thirteen acres and nine slaves. By 1860 his personal property is valued at $10,700, and his eldest son, Oliver Hardy, is listed as ‘overseer’.

It is no wonder then that Hardy and his compatriots mustered a year later for what they saw as a sacred cause – not only their way of life, but their livelihoods and their commercial interests. The two Magruder boys who volunteered with him were the sons of the local plantation owner, George Milton Magruder, registered in 1860 as owning an annual wealth of $25,000, and described as ‘one of Columbia’s most prosperous planters and best citizens’. Joining the tens of thousands summoned for the South, they went off to war.

Holley records:

Of the 102 soldiers mustered, at least 21 were killed in action. At least 22 others died of disease or from wounds, 42 per cent of those who fought. In addition, 21 soldiers were captured or exchanged at some point – some twice, 4 came home amputees.

Both the Magruder brothers died in the war. In 1870, the lucky survivor, Oliver Hardy, was to marry their sister, Cornelia.

Holley quotes an extract from the diary of one young soldier of Company K, Wave Ballard, who served in General Lee’s army:

Sunday, 28 June 1863

Lying on the bank of a large creek a half-mile north of Chambersburg, Pa. Black and dirty. Low-spirited thoughts wandering far away to those I love so much at home. How strange it makes me feel to see so many faces and not one familiar or friendly one among them. I often think and say to myself, ‘Only suppose the Northern Army should pass through our own country, our own dear homes, our property and everything we hold most dear, destroyed by a craven foe.’ I know it must appear equally as hard to them, and for this reason, I scrupulously abstain from every encroachment upon private property.

7 August

Had orders to move but heavy rain came up so waited a more favorable day. This day have resolved never to swear another oath.

The soldiers of Company K fought in sixteen battles of the Civil War, culminating in Appomattox on 9 April 1865. Oliver Hardy was wounded at Sharpsburg, Maryland, on 17 September 1862, in what has become known as the Battle of Antietam.

The survivors of Columbia County’s volunteers came back to a ruined country. Their part of Georgia had, at least, been spared the horrors of Sherman’s March, which decimated the South in

the winter of 1864. Their houses still stood, and their abandoned fields, but their cause was lost. The following years were full of despair and fury over the liberation of their former slaves. We do not know the deeds of Oliver Hardy, twenty-one-year-old veteran of a defeated army, in the dark period of the late 1860s and early 1870s, the years of the Night Riders, the early Ku-Klux-Klan. We do know that he lost no time in marrying – eligible men were at a high premium in November 1865 – a Columbia County girl, Miss Sarah E. Olive. But she vanished from sight, possibly died of disease, not long after, leaving Oliver to marry the daughter of the plantation owner, and thus become part of the Magruder clan.

Local Madison historian Marshall Williams unearthed two children born to Oliver and Cornelia: Lillian, born in 1871, and George M., born in 1875. A third daughter, Mamie L. Hardy, pops up in 1880. The rest is fuzzy. The memories of an old railroad man, Ed Adams, place Oliver as a line foreman for the Georgia Southern Railroad in the 1880s, putting down track between Augusta and Madison. Marshall Williams, however, found only evidence of a farming venture, followed by a partnership in a retail store. By 1877, Hardy had emerged as a local politician and Tax Collector for Columbia County. In this capacity his first mention in dispatches comes to light, contributed by local Harlem historian Charles Lord from the pages of the Columbia Sentinel, 25 April 1885, reporting the musings of one Dr H. R. Casey:

… Oliver Hardy, Columbia’s active and efficient Tax Collector. If there is a man in the county that Oliver does not know, I might almost say that man is not worth knowing, for he is bound to exercise a sort of pastoral care over his flock … It is hard to resist that good open, jolly, funful face, round as the full moon, and covered all over with smiles, and a form as far from the idea of consumption as one ever saw, but evincing a very decided penchant for the consumption of the good things of the table. I think I have heard the boys say that Oliver was a good feeder. I do not know whether he ‘lives to eat or eats to live’, but I do know that, with all this avirdupois, this Falstaffin figure, he is as polite and graceful as a French dancing master, a popular ladies’ man and is quite sure to kiss the babies about voting time; and, as he is standing candidate for life, as he says till he gets beat, he intends to take in a quantum s(u)ffiet of rations, to the end that he may never be off of foot or feed and the last end may still find him in harness …

A startling image, indeed a spitting image almost of the son that he would never see grown. The only known faded photograph of Oliver senior shows a bluff round face, balding, white-haired and whiskered, with a disconcerting resemblance to the iconic Colonel Sanders. A wounded veteran of the Confederate cause, son-in-law of the richest man in town, Oliver Hardy seemed to have found his station, and was ensconced at the South Hicks Road address in Harlem that now boasts so many fine front-load washing machines. Local lore, however, recounted by Charles Lord, has it that Hardy lost popularity by his reluctance to oppose a law that required farmers to fence in their animals to prevent them grazing freely on other people’s property (presumably the property of the Magruders), and was voted out of office some time in the late 1880s. At about this time, he also lost his wife, Cornelia. But he was not long alone. On 12 March 1890, he married Emily Norvell Tant, a widow, former wife of T. Sam Tant.

The multiple marriages and genealogy of the Hardys, Tants and Norvells can become quite confusing. The Norvells, like the Hardys, were a prominent local family, and their graves dot the cemeteries in Harlem and nearby Grovetown. Emily’s father, our hero-to-be’s grandfather, Thomas Benjamin Norvell, was also a Confederate veteran, having been wounded and captured at Gettysburg in 1863. He later became a schoolteacher, which was also the profession of his daughter. Her mother, Mary, was from South Carolina. Leo Brooks, applying his magnifying glass to the Norvell family tree, uncovered records showing that both Emily and her father were fired by the Columbia County School Board in 1879, and this was promptly followed by Emily’s marriage to T. Sam Tant, an unschooled labourer. Legend has it that T. Sam Tant later worked for Oliver Hardy senior on the railroad. He did not last the course. He died at about the same period as Cornelia Hardy, and his tombstone has recently been found in Grove Baptist cemetery, marked only with a barely legible name. Emily was left a widow with four small children, who now became the family of Oliver Hardy senior and were to be the siblings of Our Hero.

Rumours circulating at the new couple’s next port of call, the town of Madison, reported to Leo Brooks by an extremely aged local resident, appeared to suggest that Emily’s first child, Elizabeth, had been born out of wedlock, and this was the cause of

the termination of her teaching appointment and her first marriage to the unschooled Sam Tant. Oral history being fragile, no one can confirm this, and the gossip did not deter Oliver Hardy, who took the entire Tant brood under his capacious wing. Within a year, a new child was conceived.

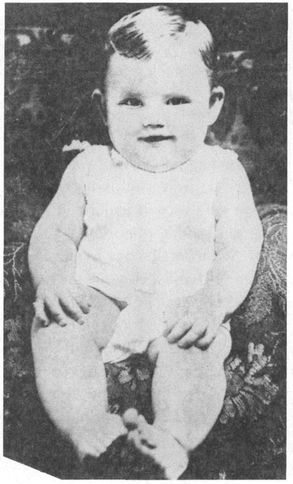

Thus, on 18 January 1892, sired of Oliver and Emily (née Norvell) Hardy, our second waif arrives in this world. He was named Norvell Hardy, to preserve the memory of both these families scarred by the Civil War. The surviving baby photograph, presenting him propped on a cushion, is without the shadow of a doubt the Ollie we know. The charming moon face, the eyes gazing out at us, cheerful but a little quizzical, not quite ‘here’s another nice mess you’ve gotten me into’ but a lively intimation of things to come.

By the time of Norvell’s birth, his father had left Harlem and Columbia County for Madison, in Morgan County, about eighty miles to the west. Oliver Hardy, having lost his Tax Collector’s office, and sold the family farm, was seeking a new business to support his wife and stepchildren. In 1891, he had found a new métier – as a hotelier, taking over the proprietorship of a hotel in Madison, the Turnell – Butler. He moved with his family but for some unrecorded reason Emily returned to Harlem to be with her family in the latter stages of her new pregnancy. Thus it was that baby Norvell was born in the family house in South Hicks Road and then carried back, by his mother, to Madison.

Within months of this return, however, tragedy struck the widow, as her new husband, the ebullient and food-loving ex-politician, dropped dead, ‘in the twinkling of an eye’, on 22 November 1892, just three days short of Thanksgiving.