Running Frantically through the Streets

‘Exploitation Suggestions’ from MGM’s press sheet for The Second Hundred Years:

Get two men to impersonate Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy as they appear in this picture. Attire them in convict suits as indicated in posters and lobby display cards. Have them run frantically through the streets in the neighborhood of your theater. Pin placards on their back announcing the showing of The Second Hundred Years at your theater. Imagine the attention this stunt will get!

Indeed. It is interesting to note that this gimmick is exactly the same as that used by Fred Karno to advertise his Jail Birds sketch thirty years earlier. It perfectly illustrates Charley Chase’s adage that the best comics recycle gags that are fresh in the memory despite the fact that the public has forgotten them. (And it invites the question whether Stan’s convict larks with Larry Semon in 1918’s Frauds and Frenzies owed more to Stan’s Karno-trained memory than to Semon’s ideas – note that Stan had already made No Place Like Jail for Hal Roach a few weeks earlier.)

The Second Hundred Years marked the return of Leo McCarey, who would ‘supervise’ or direct the next eighteen Laurel and Hardy movies. These would include a fair number of their most classic titles, some of them unarguably masterpieces of the short comedy film: Putting Pants on Philip, The Battle of the Century, The Finishing Touch, From Soup to Nuts, You’re Darn Tootin’, Two Tars, Liberty, Wrong Again and Big Business. That’s quite a lot of masterpieces, and all shot in a sixteen-month period, between summer 1927 and December 1928! Speculation can add to the list the film preceding Philip, the ‘Holy Grail of Laurel and Hardy movies’, Hats Off.

Remade and revamped as The Music Box in 1932, Hats Off introduced the boys’ most iconic setting, the grand flight of steps in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles, between 923 and 937 Vendome

Street. Instead of a piano, the boys were carrying a washing machine up the steps, to sell to Anita Garvin at the top, only to discover she just wants them to post a letter for her. This missing film introduced one of the trademarks of the best silent Laurel and Hardy comedies, the grand finale of Mutual Assured Destruction – in this case, a massed ripping of hats which spread from the two protagonists to the entire street. This scene was shot, as were many subsequent finales, in Culver City’s pristine centre, a small-town locale that would ironically become familiar to audiences around the world, from Santiago to Shanghai. The scene allegedly derived from an incident at one of the Roach lot’s raucous parties, in which Mabel Normand pulled Leo McCarey’s tie open and inspired him to go around the room pulling off everybody else’s tie. Or so McCarey chose to tell the tale.

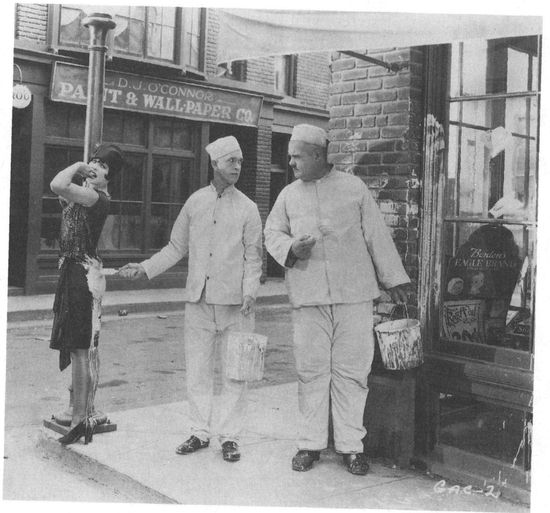

Whitewash in The Second Hundred Years

MGM once again went to town on promotion, sending out

trucks and buses plastered with posters for the film, advertising in Ralph’s groceries and Owl’s Drug Stores and putting vast billboards up all over the city. It all paid off, as the Los Angeles Evening Herald raved on 9 March 1928:

HATS OFF

This glorious slapstick occupies a subordinate position on the bill to Tillie’s Punctured Romance, a feature-length attempt at humor, but it saves the day as far as entertainment is concerned. It is no exaggeration to say that the entire audience bordered on hysteria at the climax of this two-reeler. They were really laughing at the same gag used in the first Laurel and Hardy comedy. But the substitution of hats for pies proved enough of a variation in the recipe to secure an equal reaction.

In my opinion, Hal Roach has the most promising comedy team on the screen today in Laurel and Hardy. It is to be hoped he withstands the temptation to promote them into five-reel features, a horrible example of which is on the Metropolitan bill in Tillie’s Punctured Romance.

The unfortunate supporting feature on this programme was, alas, W. C. Fields’s last but one silent film for Paramount Pictures, co-starring Chester Conklin. The pies mentioned in the review referred to Laurel and Hardy’s next but one movie, The Battle of the Century, released on 31 December 1927 – the release dates of these Roach films can be quite confusing, but the hats were definitely shot before the pies! In effect, the first Laurel and Hardy films came out in a burst at the turn of 1928, contributing to the sudden realization that comedy had obtained its true new heroes.

This was all the more gratifying to Roach and his new stars, since the greatest technical upheaval in the history of the motion-picture business had been signposted, in October of 1927, with the release of Warner Brothers/First National’s The Jazz Singer. Al Jolson’s wailing ‘Mammy’ marked the birth of the Talking Picture era. Jolson’s atrocious tear-jerking would not kill the silent movie overnight, as studios pondered the cost of total re-equipping, from set to theatre, with the new sound equipment. Hal Roach would bite the bullet himself in October 1928, announcing a deal with the Victor Talking Machine company and predicting that ‘at the Hal Roach Studios the most progressive strides will be made towards not only the perfect synchronization of short subjects but also the introduction of comedy through the spoken word’.

This left Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy a full year and more to

make their mark on the final phase of silent cinema comedy. Their last silent picture, Angora Love, was shot in March 1929 and released at the end of that year. By that time, not only the silent cinema, but the whole apparently non-stop party of America’s 1920s, the age of the flapper and the flivver, the hot cha-cha and all-night dancing in speakeasies, had been brought to a juddering halt by the Great Wall Street Crash of October 1929. And even that did not stop our boys.

Many years later, Stan certified to his authorized biographer, John McCabe, that Putting Pants on Philip and Battle of the Century were the first two proper Laurel and Hardy movies, though as we have seen they came pretty far down the line. The point is that neither Stan Laurel nor Babe Hardy were much concerned to place landmarks, or make historical judgements, or see themselves in the same iconic light cast by their adoring fans. They considered themselves, to the end, two working actors who happened to have hit on an incredible streak of good luck, after years of daily grind. They were happy to recall the good times and airily dismissive of the bad.

The eponymous pants put on Philip have been discussed endlessly by fans and critics, donned, undone, flapped in the wind and pressed into the service of any number of theories, potty or profound. The tale, as everyone knows, is of the respectable gent Piedmont Mumblethunder (Ollie), who goes to the dock to meet his nephew Philip (Stan), who has just come over frae the auld country, complete with sporran, tam o’shanter and kilt. Continually embarrassed, Piedmont has to cope with Philip’s mad chases after a girl and his penchant to draw a crowd wherever he comes into public view. Long before Marilyn Monroe excited avid filmgoers by having her skirt blown upwards by a vent in the pavement, Stan made the good ladies of Culver City faint by standing above a shaft of air that firmly settled the question of whether Scotsmen wore anything under their kilts. Finally, determined to take no more, Piedmont drags Philip to the tailor to de-kilt him and measure him for trousers, setting off an early sample of a recurring Laurel and Hardy theme, the comic male near-rape and emasculation of Stan by Ollie – the symbolic kilt standing in for more than the delicate members of the audience might wish to contemplate, or as much as their imagination wishes to engage. As Ollie and the tailor wrestle

the weeping Stan to the floor, the sexual innuendo is as clear as it will ever be in a Hollywood movie, comic or not. Walter Kerr wrote:

The fact that the assault is taken as homosexual and Laurel doesn’t even know what homosexuality is is simply an indication that the once knowing and aggressive Laurel is becoming as childlike as Roach envisioned and Hardy already looked. Laurel the victim, Laurel the put-upon, Laurel the go-and-stand-in-the-corner booby is well on the way to being born.

But the fact that Philip has spent the first part of the film knowingly chasing women – and not, I suggest, because he thinks they carry lollipops under their skirts – does make us suspect his prepubertal innocence. Both Stan and Ollie know very well what they are up to: all the comedians knew, after years of traditional cross-dress training, how to get away with things the censor hated but the audience loved. Everyone winks and pretends to see what is convenient, but the clowns appreciate, despite their protests of innocence, the well of pain, embarrassment and confusion from which they draw so many laughs.

The finale, in which Piedmont and Philip stage a rival contest to chat up the flighty Dorothy Coburn, restages the gag from Why Girls Say No, shot in 1926, with Babe as a cop. Stan puts his kilt down over a puddle for the girl to walk over; she jumps over it; Babe elbows Stan aside before he can recover the kilt, steps on it, and falls into a six-foot hole. Cue the first of many fade-outs to Ollie’s soaked and sorrowful face at the camera.

In Battle of the Century, whose title refers to the Dempsey – Tunney Heavyweight Champeenship fight of September 1927, Stan gets KO-ed by Noah Young after a pastiche of the famous ‘long count’ of the iconic brawl. (The referee keeps interrupting the count as Stan refuses to move back to the proper corner after he has knocked his opponent down by pure chance.) Somewhere in the sieve that is silent-film preservation the next five minutes or so of the film got lost, but Stan himself preserved the memory of it in an interview with Bill Rabe:

I’m just sitting there, one of those things … Gene Pallette comes along … he’s selling insurance, cheap insurance. For a dollar, Hardy can insure me – for a broken arm he gets $150, for a broken back, two thousand … [Hardy] says, ‘How much?’ He says, ‘For one dollar, you know, he’s one of those fast guys.’ So Hardy … takes out this phony insurance … so

from then on Hardy’s trying to get me hurt. See, he’s walking me under ladders – of course, he gets the brunt of everything – brick drops on him. Tries to put me in front of a streetcar, another one comes along the other way and hits him …

This culminates in a banana joke, on which the film we have picks up, with Hardy trying to get Laurel to slip on the banana skin but instead bagging first a cop and then pie-vendor Charlie Hall. This leads to Stan and Ollie’s most famous ‘reciprocal destruction’ sequence, the greatest pie fight of all time. In Stan’s words:

There’s a dentist, and a guy’s with his mouth open when the pie comes in – you know, you never saw where it came from. But every gag was a belly laugh, you know, and before you know, it snowballed, and the whole town is eventually pied, I mean, the wagon [unintelligible, as Stan bursts into hysteria].

Both Putting Pants on Philip and Battle of the Century were directed by Clyde Bruckman, who had co-directed Buster Keaton in The General and was later to tangle both with Harold Lloyd and W. C. Fields. He, too, played his part in nudging our heroes along towards the roles that would become so well known.

Once both Stan and Babe had settled on the characters that made the Laurel and Hardy films work, and engage the audience, they locked them in, and stuck to their last, for the next thirty years. Like Chaplin, they had finally found masks that required no further development as characters, only a proper stream of situations, stories and gags that would test their capability to cope with the endless tasks and obstacles thrown in their way. This was the key to their recognition, throughout the world. Other comedians buckled under the strain: the Marx Brothers were soon tired of their unremovable masks, Groucho in particular; W. C. Fields became the character he had invented and his real self disappeared from view; Mae West got fat; Lloyd became too old to be the eternal glasses boy; Keaton could not convince the sound-era studios to allow him to grow under his own power; even Chaplin had to doff the tramp’s costume when Adolf Hitler galvanized him into a more direct engagement with the terrors of the real world. But Laurel and Hardy stayed the same. The actors grew older, and Babe Hardy’s battle with his own girth took its toll eventually, and entropy and the incompetence of the corporate studio system

pressed upon them, in the fullness of time, but, for their legions of fans, they stayed the same. Everything else could disappoint: friends and spouses could be inconstant; time laid you traps of disappointment, hardship, injury, disease; economies could crumble; politicians deceive; wars ravage the earth; a thousand and one pinpricks could afflict you, and death lie ever smirking round the corner. But Laurel and Hardy stayed the same, and were regenerated, in the magic of television, video cassettes, and, in the words of publishers’ contracts, ‘any media yet to be invented between now and the end of the world’.

The comedy techniques of Laurel and Hardy have been analysed forwards and backwards, examined under microscopes and magnifying glasses. Without doubt the real miracle of the Great Leap into Immortality lies in the boys’ achievement in bridging the painful transition from silent films to the talkies that left so many actors, comic and dramatic, beached like dying whales on the shore. Stan and Ollie’s apparent bad luck in emerging as silent-movie stars at the very moment the silent cinema was doomed was turned into their greatest stroke of good fortune. Just why this occurred is one of those intangible things that can easily be a tautology: they succeeded because they succeeded. The audience, entranced, was just not willing to let them go. But plenty of popular stars – Keaton being the most prominent – were doomed by circumstances, or studio intransigence. Harry Langdon, making a succession of bad choices, disappeared almost completely, only to appear in a very different guise from his star status in Laurel and Hardy annals.

Walter Kerr defined what he called ‘the second Laurel and Hardy turnaround’ in the change of pace from comedy’s customary frenetic rush to the more leisurely step of Ollie’s graceful movements – ‘the soothing guidance of a steady 2/4 beat, the mellifluous promptings of a chastely tuned pianoforte’. But of course we have seen that Babe himself did not develop that pace before the Teaming, and so we are back to the mystery of the guiding hand – not the single-minded insight of the lone genius, but the combined genius of the movie makers: Roach, McCarey, Stan and Babe. Writes Kerr, ‘If the front man was slowed down by the delicacy of his nature, the second man, Laurel, had to be slowed further still, rendered all but inanimate as he waited for his master’s cue. How,

then, were the gags to be performed?’ The answer, Kerr pointed out, was quite simple. They did not invent new gags, or do anything that comedians before them had not done; they stepped on the same banana skins, threw the same pies, crashed into cars and so forth, but:

They confessed to the joke … explained it most carefully, anatomized it … Here, you see, is Mr Hardy climbing out of bed to get a hot-water bottle for Mr Laurel, who has a toothache. Here, on the floor between the bed and the bathroom, is a tack. Here comes Mr Hardy, stately in his kindliness and blind to his peril. Here is Mr Hardy stepping on the tack, howling in pain and plucking it from his bare foot. Here is Mr Hardy throwing the tack away with infinite disgust. Here is Mr Hardy in the bathroom, filling the hot-water bottle, and returning to the bedroom. Here, once again, is the tack on the floor, exactly where Mr Hardy has thrown it …

And the inevitable follows. The joke was no longer a secret, lying in wait, it was ‘a ritual through which the well-informed were courteously conducted, a ceremonious tour of well-marked terrain’.

This ritual is perhaps the most important element that enabled the popularity of Stan and Ollie in almost every country of the globe. Chaplin was a universal comedian, whose tramp character appealed across all frontiers. But Keaton and Lloyd, for example, were quintessentially American: their need for problem resolution through action – Keaton’s tremendous chases; Lloyd’s rush through life’s perils to win true love – are defining icons of 1920s America, the urgent social climb, the necessity of speed. These are also individual values, the core of the American Dream. And many previous comedy teams, like Babe’s own Plump and Runt, or Pokes and Jabbs, or Ham and Bud, were more often than not just two separate individuals, scrapping against each other for a place in the sun, typical marriages of inconvenience. Stan and Ollie, on the other hand, were two halves of an organic whole – once matched, they could not be split asunder. Together, they struggled through the obstacle course of ornery reality. Anyone, anywhere, in any country, could identify with this continual battle, which may be propelled forward by ambition, but which proceeds in a circular fashion back to the state of failure and helplessness from whence it often came. Speed is not of the essence – there is little point in rushing if one

can proceed more sedately, and with the proper dignity, towards inevitable disaster.

When, in You’re Darn Tootin’, Stan and Ollie are unable to walk down an ordinary street without falling down a manhole, their struggle for survival has been reduced to its most primal level. Watching these seminal scenes, we might pay attention to other crucial elements of the boys’ movies – their crew of regular collaborators, who accompanied them throughout the Roach years. Richard Currier cut almost every film made at Roach, if one believes the credits, until late 1932, giving the Roach mob a certain rhythm that marked them out from their competitors. Principal cameraman George Stevens would remain on the team till 1931. In You’re Darn Tootin’ – whose cameraman, as chance would have it, was second stringer Floyd Jackman – the camera’s contribution is marked in the way it precedes Stan and Ollie down the street in a close-shot and allows first Stan, then Ollie, to fall out of the screen while the other continues blithely for a while, looks back, and the camera dollies out to the long-shot of the fallen one in the hole, legs waving in the air, while he who remains upright glances long-sufferingly into the lens.

The ritual element is at its clearest in the great denouement of You’re Darn Tootin’, when a long poke-in-the-eye kick-in-the-shins tit-for-tat between Stan and Ollie leads to the ripping of pants off every passer-by who crosses the screen, including, of course, the inevitable cop. The frenzy of debagging that convulses everyone repeats the follies of the great pie fight, but at a much more surreal pitch. The camera stands back and observes, almost neutrally, as utter madness grips the sidewalk on which Stan and Ollie have begun the sequence innocently attempting to ply their desperate trade of street musicians, to which they have been reduced after losing their jobs in the orchestra in the first part of the picture, and their accommodation in the second. Randy Skretvedt has written of this:

You’re Darn Tootin’ is the first clear statement of the essential idea inherent in Laurel and Hardy. The world is not their oyster: they are the pearl trapped in the oyster. Their jobs hang by rapidly unravelling threads. Their possessions crumble into dust. Their dreams die just at the point of fruition. Their dignity is assaulted constantly. At times they can’t live with

each other, but they’ll never be able to live without each other. Each other is all they will ever have. That, and the hope of a better day …

The rituals were honed, perfected, and became second nature, as Laurel and Hardy meshed ever closer. In The Finishing Touch, two titles earlier than You’re Darn Tootin’, the already rehearsed cadences of Stan’s solo Smithy were honed with balletic precision. Instead of Jimmy Finlayson as foil Stan has Ollie, his match in house-building incompetence. The gag with the endless plank, with Stan at each end, is lifted straight out of The Noon Whistle and, instead of a tack, Ollie has a whole bucket of nails to step on, trip over, and swallow. Two external foils are provided by the ever fearsome Dorothy Coburn and another Roach regular, Edgar Kennedy. Every possible carpentry gag in the universe is dusted down and used, then played again. When Stan and Ollie’s bickering releases the truck at the end to roll into the finished house and demolish it, we recognize the deep footprint of fate.

Precision, as all the great clowns knew, is everything when dealing with chaos. Stan has gone on record as stating that the Laurel and Hardy films were shot in chronological order – an unusual and, today, prohibitively expensive method. ‘The only place I could do it was at Roach,’ Stan declared. ‘Anywhere else, they wouldn’t go for that.’ And of the scripts:

Well, we had a rough outline of a story. And we had lines, to motivate what we were going to do … or what the plot was about, naturally, but as far as the Laurel and Hardy scenes, those were worked out practically on the set … You rehearse a scene, and then try to improve it; if it looks OK, you shoot it, and if you think you can make it better, fine. Occasionally things would crop up and we’d kind of ad lib and do something else. But not too often. It was pretty well cut and dried. And we had a lot of mechanics. Sometimes they didn’t work. Like an explosion where everything, the walls fell down, the drapes and all else, all that was wires and what have you, sometimes they got fouled up, sometimes in the middle of a scene a carpenter would come in the window and say, ‘Did it work?’

One of the greatest of all mechanical challenges came in Two Tars (late 1928). Stan and Ollie are sailors on shore leave who pick up a couple of girls and have a wrestling match with a recalcitrant bubble-gum machine, watched over by shopkeeper Charlie Hall. This is merely flapdoodle to bring us to the grand part two of the

two-reeler in which the boys and their gals get stuck in a traffic jam caused by roadworks. The subsequent wreckage of vehicles would make any old or new Luddite proud. Here, at last, is America’s pride and joy, the flivver, the Model T Ford and all its rattling offspring brought to a cataclysm of torn fenders, broken windshields, wrenched-off wheels and doors and entire chassis mangled to cartoon shapes. Never has tit-for-tat destruction looked more satisfying. Stan told interviewer Bill Rabe, who asked him, ‘How many Model Ts did you have?’

Oh, we had them specially made. One in a half-circle that would go around and around, then we had one that was squashed up between two cars. It was tall, we were sitting high up in the air, up in the front seat. Then we had one that went into a railroad tunnel, and a train would come through at the other end, and we came out with the four wheels practically in line … There were no motors in them, you know, they were just breakaways; and we had one that was all fitted together, and you pulled wires and everything collapsed, at one time! [Stan laughs uproariously.]

In classic form, the thread of convention and civilization unravels, as one small insult begets another until all drivers and passengers

are engaged in their orgy of mutual destruction. Not for nothing have Laurel and Hardy become metaphors of our social and political mores, as the clowns, without seeking to do more than amuse, peer more clearly into the mechanisms of our follies and just say, ‘What if I pulled that small wire?’ Down comes our fragile edifice of deception. And at the end, as the mangled cars go by, some upended, some wheelless, shouldered by their passengers, another bouncing and juddering down the road as if afflicted by vehicular ague, the two miscreants who started it all look on, collapse in mischievous laughter, and, as instantly, freeze into seriousness as the watching, helpless cop – whose own motorbike has already been flattened to a tin rag – wags his finger: ‘You’re going to pay damages for this!’

By now, our heroes are well established. They have long stopped being called Ferdinand Finkleberry, or Sherlock Pinkham, or Canvasback Clump. They are now fully ensconced on the screen as themselves, Mr Laurel and Mr Hardy. The masks have replaced the persons, and can address us directly, without subterfuge. There is nothing up our sleeve. We are naked in daylight. Like Popeye, we answer the existential question with the oldest answer of all: ‘We yam who we yam.’