Full Supporting Cast: The Lot of Fun

Nineteen twenty-eight, the Hal Roach Studios: the ‘Lot of Fun’ as it was called, principally by its own publicists. Despite Roach’s determination to pay his employees as little as possible, and keep them on contracts that served his interests – his insistence on separate contracts for Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy was to be a bugbear for years to come – the alumni remembered those days with a golden glow. These were the years when they were encouraged to exchange ideas, to develop their own, to see themselves as collaborators in a unique project devoted to comedy and its rewards – the esteem of colleagues and audiences, not to speak of earning a living in a country where prosperity was soon to hit the buffers with a terrifying crash.

A surviving Hal Roach Studios ‘datebook’ might present a somewhat lackadaisical approach to the business of running a large enterprise with numerous projects and offshoots working away at the same time. The ‘datebook’ is a simple lined notebook with the entries scrawled in ink. The year 1928 begins with Monday, 2 January, entered as ‘Holiday’, then the main crew present on each location is listed:

| Tuesday, 3 January | |

| S – 8 | Kennedy, French, Driscoll, Powers, Ireland, McBurnie(?), Williams |

| Laurel Hardy – stage | |

| G – 8 | McGowan, Sandstrom, Jackman, White, Boshard |

| Kids – stage | |

| S – 8 | Hy East and Buddy |

| G – 8 | mule – Moore(?) + Blunt |

| G – 8 | Tony and Duke + Jiggs |

| G – 8 | Bob Sanders dog |

| Harold Lloyd Co – on tread | |

| Wednesday, 4 January | |

| s-8 | same as yesterday – stage |

| G – 8 | same as yesterday – stage |

| G – 8 | horse – Moore – Blunt |

| mule – Jones | |

| ostrich – L.A.O. Farm | |

| Tony – Duke + Jiggs | |

| Bob Sanders – dog | |

| S – 8 | Hy East + Buddy |

| Harold Lloyd on tread | |

Roach still seems to have been churning out his animal pictures, though the short-lived Dippy Doo-Dads had been dumped. The summer entries recorded:

| Monday, 2 July | |

| L – 13 | Laurel and Hardy – Parrott, French, Black, Stevens, Hopkins, White, Collings(?) |

| G – 14 | Lloyd and Kids |

This must refer to the shooting of Two Tars, which wrapped on 3 July, George Stevens having photographed the film, with Jimmy Parrott directing. On 8 August we have:

| S – 15 | Parrott, French, Litefoot, Stevens, Davidson, L&H |

| L – 14 | nite retakes – cemetery |

Clearly a reference to Habeas Corpus. At the same time, on floor S – 15, the notebook records: ‘Tony and dog.’ On Thursday, 23 August:

| L – 15 | Laurel & Hardy Stage 2 |

| McCarey – Scott – Black – McBurnie – White | |

| S – 15 | Retakes using 2 goats |

| S – 15 | Retakes used our own goat |

| Friday 24 August | |

| Retakes using cow | |

And so forth. Roach was at this point, though still keeping his eye on the creative processes, more and more involved with the financial aspect. His distribution deal with Metro Goldwyn Mayer gave the studio a healthy balance sheet of current assets, posted on 28 July 1928, of $1,856,895 against liabilities of $215,826. Roach was still paying Stan no more than $33,150 throughout the year and Oliver a meagre $21,166.67. The second half of the year –

after Roach returned from a five-month round-the-world reconciliation tour with his wife, from January to May – was taken up with Roach’s plans to grasp the nettle of the new technology and re-equip the studio top to bottom for sound. The Los Angeles Examiner of 10 October 1928 reported:

By the terms of contracts just signed between Hal Roach and the Victor Talking Machine company, the Hal Roach Studios in Culver City, Cal., will be allied for many years to come with the reproducing facilities of the Victor organization …

Everyone in Hollywood was already hiring voice coaches, dreading that their larynxes would cause the abrupt termination of their movie careers. Anita Garvin remembered her fears on hearing her first sound recording: ‘I thought, “Oh my God! Here I am lisping all over the place! I’m finished, I’m finished!” But fortunately, the next person in the scene did the same thing, so I knew it was the soundtrack and not me.’

But these horrors still lay in the future, as 1928 continued its crop of Stan and Ollie silent classics, wrapping up the year with Liberty, Wrong Again, That’s My Wife and Big Business, all shot in a period of just over two months. The stock company was forging forward at full speed.

By now, most of the regulars who would become familiar to legions of Laurel and Hardy fans were in place, apart from Billy Gilbert, who would appear in the talkies, and Mae Busch, who had touched base with Stan and Ollie in Love ’Em and Weep and would rejoin them in their first sound film, Unaccustomed As We Are, in 1929. We have already been introduced to Anita Garvin, who was also doing sterling work with Charley Chase, and was to appear in three films teamed with another Roach starlet, Marion Byron, in 1928 and 1929. A New Yorker, Garvin had toured with the Ziegfeld show, Sally, and dropped off in California, appearing in a few short films before her meeting with Stan at Joe Rock’s. No one can forget her coruscating performance in Stan and Ollie’s From Soup to Nuts, shot between The Finishing Touch and You’re Darn Tootin’, in which Anita, as the haughty society hostess, Mrs Culpepper, who has been unlucky enough to hire our heroes as waiters for her dinner party, chases a cherry around her plate with a spoon while her tiara keeps slipping down over her eyes. This is

a reprise, as we have noted, of the dinner scene at prison governor Fin’s house in The Second Hundred Years, but Anita is a more inspired choice as the cherry chaser. Her attempt to maintain her sang-froid in this struggle, while Ollie is performing serial pratfalls into the cake, is one of silent comedy’s best moments. Note, in this scene, how the gag, again, is prefigured, with the family dog carefully placing a banana skin, in close-up, on the carpet, so that we know Ollie is due for the fall. In his next attempt to serve the cake, the banana skin is still present, and spotted by Stan, who, rather than remove it, places his hand over his eyes, while the inevitable once more occurs.

Anita’s husband in the movie, Mr Culpepper, is played by Tiny Sandford, all-purpose heavy, cop, prison guard, waiter and general surly visage of authority. A very tall gentleman, six foot five inches without socks, Stanley J. Sandford was born in Osage, Iowa, and spent his formative years with the Daniel Frawley stage company in Seattle and Alaska. He appeared in films since at least 1910, and was said to have played the card player who has an altercation with Chaplin in his seminal short, The Immigrant, in 1917, though historian Glenn Mitchell notes the actor in question was in fact the much shorter Frank J. Coleman. History will remember Tiny Sandford best as the representative of Culver City’s finest who sits in his car and notes every move of Stan and Ollie’s destruction of Jimmy Finlayson’s house and his reciprocal demolition of their car in Big Business. Every fresh outrage prompts a breathless take, a lurch forward, a lick of the pencil and a feverish new charge written down in the policeman’s notebook. Like Anita Garvin, Sandford had one of the faces that have become attached as icons to the silent comedy, recognized by viewers who have long forgotten the name or the title of any movie in which they appeared.

Charlie Hall was another screen foil, as small in frame as Sandford was large. Another transmuted Englishman, he had been born in Birmingham in 1899 and was reputed to have come over the pond with Fred Karno, though there is no evidence that he ever worked for the Guv‘nor. Despite claims that he had known Stan Jefferson way back when, all the signs are they met while Stan was working for Larry Semon. His first appearance in a Laurel film was in 1923, in The Soilers, and he also appeared in Stan’s Near Dublin and beside Babe and Charley Chase in Bromo and Juliet. Apart

from his role as a bit-part actor, Charlie was also a carpenter on the Roach lot and advertised for work as ‘Comedy Relief and Characters’ in the Hollywood film magazines. From late 1928, Hall was a regular in Laurel and Hardy movies, and was eventually to clock up forty-seven appearances in their films. In Two Tars he was inaugurated as the feisty and permanently aggrieved shop owner whose small world is always under threat by the forces of chaos who come tripping, in tandem, into his life. He had to wait until 1935 to get his on-screen revenge, in Tit for Tat, where the boys are foolish enough to have set up their electrical shop next door to his grocery, having already frivolously flirted with his wife in their previous movie, Them Thar Hills.

Another Charlie, and another Englishman, was Charlie Rogers, who played small parts in Two Tars, Habeas Corpus, Double Whoopee and several other Stan and Ollie films, but whose main contribution was as a gag writer said to be second only to Stan on the Roach lot, and as a director, who was to helm a few of the boys’ mid-1930s shorts (Them Thar Hills and Tit for Tat, for two) and features – Fra Diavolo, Babes in Toyland and The Bohemian Girl. He had appeared with W. C. Fields in So’s Your Old Man, in 1926, and had apparently met Stan a decade earlier, in the vaudeville period. Another, closer companion of Stan’s vaudeville years who was employed in the boys’ films, Baldy Cooke, is less recognizable to fans, but turns up in the periphery of such classics as Two Tars and County Hospital, where he dons the garb of a doctor, and Perfect Day, in which he appears as a neighbour.

Edgar Kennedy, on the other hand, was a more full-fledged foil, whose prodigious output stretched to performances in over two hundred short films and about a hundred features. Born in 1890 in Monterey, California, his early career see-sawed between singing in musicals and knocking out opponents in the boxing ring. His first film, according to the annals, predated even Oliver Hardy’s – Hoffmeyer’s Legacy – for Mack Sennett’s Keystone in April 1913. Often a policeman (though not necessarily a Keystone Kopper), he romped alongside Ford Sterling, Fred Mace, Hank Mann, Mabel Normand, Mack Sennett himself and the newcomer, Charlie Chaplin, in 1914. In 1915 he became a regular foil for Fatty Arbuckle. A stint in features in the mid-1920s led to Roach, and his first role in a Laurel and Hardy film, Leave ‘Em Laughing, in the

classic cop role. Stan and Ollie have got themselves both laughing-gassed at the dentist and drive off, chortling uncontrollably. Edgar’s efforts to get the traffic moving only reduce them to helpless fits of mirth, increased every time his furious face glares at them in incomprehension: ‘You’re practically in jail right now!’ he grits at them, as his trousers fall over his ankles. Eventually despairing, he gets into the driver’s seat, only to drive them promptly, laughing even louder, into a ten-foot water hole.

Kennedy was the movies’ quintessential Irish cop, with his stubborn belief in the virtues of his own authority, despite it always being mocked by the world. He developed his trademark ‘slow burn’, the puffing of that balding, potato-like face and the narrowing of the eyes expressing the mounting rage against unsurmountable subversion, seen to great effect in his soft-drink-stall war with Harpo Marx in Leo McCarey’s Duck Soup. But he was not just a pretty face, as the credits show us that, as ‘E. Livingston Kennedy’, he directed two of Stan and Ollie’s finest silent shorts, From Soup to Nuts and You’re Darn Tootin’.

Edgar’s greatest ordeal was to come in the talkie picture Perfect Day, in which, as the grumpy uncle, he is loaded in the boys’ car with his gouty, heavily bandaged foot hanging over the side, in preparation for the picnic that is not to be. Never was a foot subjected to so much hammering, smashing of car doors and general battery.

Kennedy was, in that film, a replacement for Jimmy Finlayson, who had rejoined the Roach lot after a few months spent looking for his fortune in other fields, namely Warner Brothers/First National. He rejoined Stan and Ollie for a small role in Liberty, as a shop owner whose gramophone records are smashed to smithereens in the usual manner (the triple-double-take in fine fettle), but he played the role for which he was undoubtedly welcomed into heaven in Big Business.

Selling Christmas trees in California – not in the summer, as some commentators have ignorantly alleged, as the film was shot over the Yule 1928 period, and the boys are wearing heavy coats despite the sunshine – Stan and Ollie, after a few false starts, arrive at Fin’s house determined to make at least one sale this day. The subsequent mayhem, as Fin begins by snipping the tree up with shears and the boys tear the bell off his door jamb, represents the

most perfect metaphor in the movies of the human condition of short-sighted response. He does it to me; I’ll do it to him. They trash his house, pull up the trees in his garden, chop up his piano. He reduces their car to metal shreds with his bare hands, dancing on the wreckage. Conflict resolution is provided, as we have noted, by Tiny Sandford, who, having asked the ritual ‘Who started all this?’, prompts the combatants to tearful and seasonal reconciliation, only to find Stan and Ollie laughing at him behind his back. End with chase into the distance, as Fin discovers the cigar he has been handed by his enemies inevitably explodes in his face.

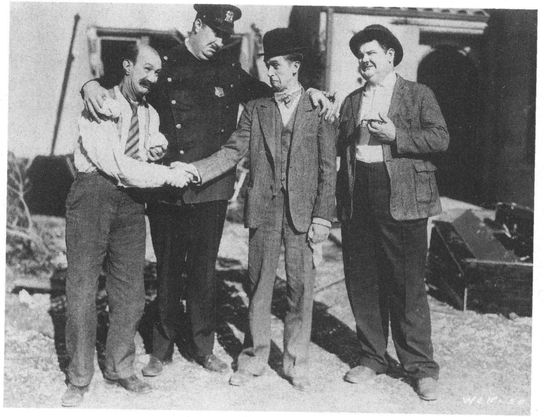

Conflict resolution in Big Business, with Jimmy Finlayson and Tiny Sandford

One of the funniest of all films, Big Business is capable of reducing an audience, seventy years after its production on the Roach routine schedule, to hysteria. Here the triple act is working at full steam, with Fin as the perfect equal of Stan and Ollie, marking a solid triangle of action-reaction-super-reaction. In tragedy, chaos is unleashed, and pain and suffering ensue from folly. In comedy, pain and suffering transform into cathartic relief. (That’s as far as I intend to go about why people find things funny.) And the rest is box-office history.

A host of other talents waltzed through Stan and Ollie’s movies: Dorothy Coburn was the fist-waving nurse from the next-door sanitarium in The Finishing Touch, and the flighty flapper who causes Ollie to step in the puddle in Putting Pants on Philip. Vivien Oakland was a blond harridan wife who scared the bejasus out of many screen husbands. Viola Richard and Daphne Pollard did time as Stan’s or Ollie’s wives. Thelma Todd was about to come on board, as have noted. Stan and Ollie’s last but two silent, Double Whoopee, featured eighteen-year-old Jean Harlow, a terrific addition to the Roach team who was soon to blossom in other gardens, as the glamour girl who gets her flimsy dress torn off by hotel doorman Stan by mistake. She made cameo appearances in both Bacon Grabbers and Liberty.

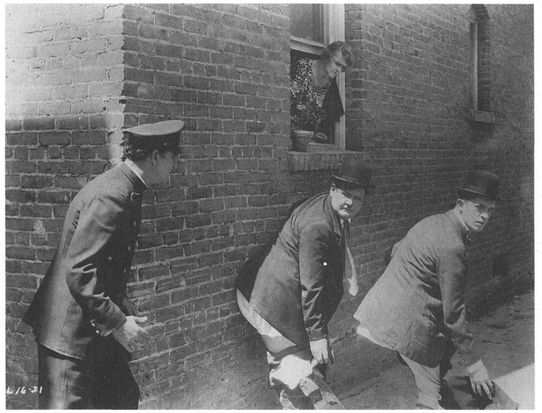

In Liberty, she played the girl who tries to get into a taxi only to find that Stan and Ollie are inside, desperately trying to change their trousers, a sight even the most seasoned flapper might frown at. Escaped from jail again, they have evaded the guards and leapt into the cab of a henchman who has brought them civilian clothes, only to find that when they have doffed their prison stripes, they have put on each other’s trousers. The entire film then follows their endeavour to change their pants back, leading them into corners, alleyways and ultimately the lift in a construction site which wafts them aloft into the steel beams of the skeletal floors high above the city.

The whole film plays on an unspoken and unacknowledged running joke on the assumption by all the shocked passers-by that Stan and Ollie are homosexual lovers trying to have sex in public. As mentioned earlier, ‘gender-bending’ and gay, or ‘pansy’ effeminacy were standard ploys in vaudeville from time immemorial. The cleverness of Liberty is that Stan and Ollie’s perfect innocence offers, again, a childlike simplicity in their continual embarrassment at being caught, literally, with their trousers down. Sex is not an issue, but a crab fallen in the backseat definitely is. As the boys twist and squirm, dancing the dance of the pull of gravity even higher above the streets than Harold Lloyd, they never lose touch with their essential characters, which underlie every gag and thrill.

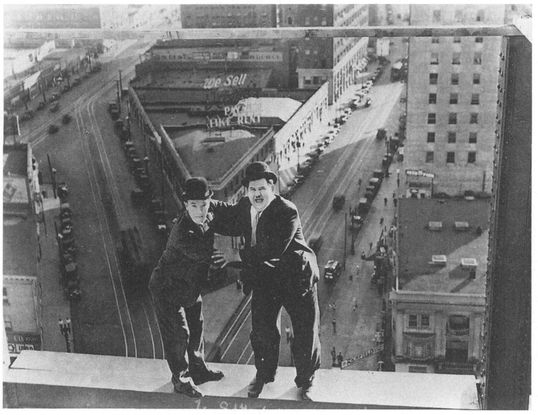

As in Lloyd’s Safety Last, no back-projection process shots were used. The studio construction crew built a three-storey set on top of the Western Costume Company building on South Broadway in

Los Angeles. Randy Skretvedt quotes set designer Thomas Benton Roberts: ‘The roof of the building was 150 feet, and we were working three storeys above that. Each time we changed the set-up for a shot, we’d have to move the camera platform around, and try to miss the flagpole on the corner of the building.’ A safety platform was provided twenty feet below, but, director Leo McCarey told an interviewer in 1954, ‘Babe said to Stan, “I’m going to show you that it’s perfectly safe.” And he jumped. Well, it wasn’t safe.’ The platform splintered, as well it would if Oliver Hardy landed on it, but a safety net below did the trick. According to Skretvedt’s research, something must have gone wrong with the footage, because the records show the actors clambering about the set again in November, a month after the initial shoot. The re-shoot was directed by James Horne.

Liberty – caught with their pants down

Leo McCarey was at the helm again for the boys’ next masterpiece, Wrong Again, in which, playing stable hands, they mistake the report of a millionaire’s missing painting, Blue Boy, as referring to the horse in their care. Luis Buñuel put a dead cow on a piano in his short Un chien andalou – shot in the same year as Wrong Again –

in the name of art; Laurel and Hardy put a horse on a piano just for laughs. The result, in both cases, is surrealism, an artifice in the first example, a natural outcome of life’s confusions in the second.

Liberty – on the high rise

A mint moment of high acting skill derived from the English music-hall can be seen in an earlier sequence in the rich man’s home, when the boys knock over a small nude statue and Ollie absent-mindedly puts the pieces back the wrong way. As Stan enters the room, he spots the strange figure, breasts pointing the same way as the buttocks, and pauses, finger poised, glancing, first at the statue, then up, quizzically, then back again, in a long series of ‘takeums’. Ollie has already told him that the rich think differently, and everything is ‘the other way’ with them. Stan’s face registers a whole gamut of questions, answers, considerations, bewilderment and finally acceptance that the strange desires and mores of people cannot be gauged. Life, for on-screen Stan, is an endless variety show of events and activities that cannot be fathomed: motivations that cannot be understood, objects that drop on your head for no apparent reason, streets with holes in them, furniture that is more often than not in the wrong place,

vehicles with uncontrollable appendages, such as wheels, utensils and tools whose function is wholly mysterious, and social structures, such as employment, finances, or marriage, which have rules that are utterly occult and meaningless, and can be survived only moment by moment.

These affairs, off screen as on, were to cause both Stan and Babe grief, and set them challenges that were easier to face in the movies than in reality.