The Song of the Cuckoos

Consummate workaholics, Stan and Ollie were getting film after film in the can. Brats, Below Zero, Hog Wild, The Laurel—Hardy Murder Case, Another Fine Mess, Be Big, Chickens Come Home (a remake of the 1927 silent Love ’Em and Weep), Laughing Gravy, Our Wife, Come Clean … There was barely time to present señora Laurel, or señora Hardy, with excuses to unwrap the double-barrelled shotguns. The Roach factory was still going full steam ahead, as, in the outside world, the grip of the Depression tightened, the lines of the unemployed stretched longer and longer, and their embarrassing shanty towns, or ‘Hoovervilles’, proliferated in major cities. Ten years later, writer—director Preston Sturges would make Sullivan’s Travels, in which a pretentious young director, played by Joel McCrea, ventures out from Hollywood into the world of the Depression’s victims, only to find himself locked up in a chain gang, amnesic from a blow on the head. But even in jail, the showing of a comedy, in this case a Disney cartoon, brings a moment of relief and healing to the oppressed, and an epiphany for the would-be social reformer. Instead of making his projected epic, ‘Oh Brother Where Art Thou’, he will devote his life to comedy.

Sturges was the scion of the kind of family that would have employed Laurel and Hardy as butlers but would not have minded if they had served the salad ‘undressed’. He saw the struggles of ordinary people from the outside, a maverick gadabout who managed, for a brief period, to pit his talent against the Hollywood system and win, moulding his own brand of stinging satire. Laurel and Hardy, on the other hand, were still labourers in the salt mines, blue-collar workers who had come up the hard way, and worked their comedy by experience and instinct. They had been tramps, sleeping on benches and goggling at the doughnuts in the kitchen through the outside window, long before these figures had proliferated in real life, to prick the conscience of the prosperous elite. In One Good Turn, shot in June 1931, Stan and Ollie appear openly

as ‘victims of the Depression’, begging for food at the home of a kind old lady. Mistaking the amateur play the lady and Jimmy Finlayson (acting the villainous landlord) are rehearsing for the real thing, they vow to save her, and the usual embarrassments ensue. This was, incidentally, the first Laurel and Hardy film to feature Billy Gilbert, a stalwart huffing and puffing supporting actor who was to join the regular crew. A singer in his teens, and then vaudeville and stage actor, he was encouraged by Stan to join the Roach Studios, but never broke free of bit parts and character roles. Although he had been born in Louisville, Kentucky, he excelled in apoplectic foreigners, most explosively in Stan and Ollie’s piano saga, The Music Box.

By now, the boys had the procedure for their productions down to a fine art. Asked ‘What would a typical day’s shooting schedule be like?’, Hal Roach related to Randy Skretvedt:

ROACH: Laurel and Hardy as a rule rehearsed all morning. They seldom photographed in the morning. They would go through the scenes and see how they would play. If they played well, they might start photographing. If the scenes didn’t play well, the gag man, with Laurel, would change them so that they would play … Laurel bossed the production. No question about that. And with any director that was directing Laurel and Hardy, if Laurel said, ‘I don’t like this idea’, the director didn’t say, ‘Well, you’re going to do it anyway.’ That was understood. Many people who directed Laurel and Hardy weren’t exceptionally great directors, but they got along well with Stan. Laurel worked hard. When they were making the picture he was working all the time to make the picture as good as he could. But unfortunately he had limitations as far as writing stories is concerned.

SKRETVEDT: Anita Garvin says that Stan had a very subtle way of working. He would actually direct the films without the director knowing it, by making suggestions.

ROACH: Well, it depended who the director was …

SKRETVEDT: How about, say, Leo McCarey?

ROACH: Oh, Leo McCarey, hell, Stan wouldn’t open his mouth. He adored McCarey …

SKRETVEDT: Often, after a picture was previewed, if something didn’t go over with the audience, you would recut or re-shoot different sequences. Weren’t you concerned about the expense involved in doing this?

ROACH: On most every picture we did with Laurel and Hardy, we previewed the picture and then redid the picture afterwards … [On relying

on the preview audience’s reaction:] After sound came in … you had to judge the length of laughter before you talked. If the dialogue was furthering the story, then if the audience laughed over it and didn’t hear the line, it didn’t mean anything … There were many times when something had happened and it was funnier to the audience than you thought it would be. Therefore you would add to that sequence. And another time you would have a sequence that you felt was very funny, and the audience would miss it completely. So you would have to cut it out and put something else in.

SKRETVEDT: We know that Laurel contributed a great deal of gags to the team’s films. Did Hardy ever contribute much in the way of gags?

ROACH: No, but the things that Hardy did himself were his. The tie, and his looking at the camera, and the way he did things individually, nobody told him. I never heard anybody, including Laurel, direct him in anything. They just told Hardy what to do and he did it … He was a hell of a good actor … I never saw Hardy at any time try to steal a scene from Laurel, and never saw Laurel try to steal a scene from Hardy … As far as working together on the set is concerned, that other team Abbott and Costello worked at our studio, and they used to fight like hell. But with Laurel and Hardy, when I fired Hardy, Laurel cried …

In 1930, however, nobody was firing anybody at the Roach Studios, and new talent was being brought in. Brats, in which Stan and Ollie doubled as their own offspring, featured special oversize sets to surround the infant boys. It also showcased a new musical title theme, the ‘Cuckoo’ (sometimes called the ‘Ku-Ku’) song, which had been first used in Night Owls. The composer was the twenty-five-year-old T. Marvin Hatley, an Oklahoma musician who was working at the KFVD radio station, located on the Roach lot. He was one third of the ‘Happy-Go-Lucky’ Trio, which also featured Vern Trimble and Art Stephenson. Stan told an interviewer:

We heard this one morning and we thought the tune … tickled us and we thought let’s get a recording made of it and put it in one of our pictures at the opening and see what the reaction would be. The audience laughed at it. So I think Roach gave the guy fifty bucks for the rights.

This was another example of ‘tall oaks from little acorns grow’ because Hatley was to become the musical director at the Roach Studios, writing hundreds of scores for a host of films, progressing from shorts to features. He was a multi-talented, energetic and endearing man who, like his music, preferred to stay in the background.

Another musician, who scored most of Laurel and Hardy’s sound shorts, was Leroy Shields, whose own music was often misattributed to Hatley. Hatley scored Laurel and Hardy’s feature films from Way Out West to their last Roach project, and was nominated for an Academy Award for his scores for Way Out West and Block-Heads. He lived to a great age, and was befriended by many Laurel and Hardy fans.

Apart from the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, it is hard to think of another musical phrase that is so immediately recognizable and evocative as the few bars of the ‘Cuckoo’ theme. The music became so attached to the image that the studio later reissued all the pre-Hatley Laurel and Hardy sound films, rescored with Hatley’s signature theme — the form in which they are seen today, in TV transmissions and videos.

Brats, ‘Ku Ku’ song apart, is a tour de force of Stan’s perennial theme of split and confused identities, and further evidence, if any were needed, of his penchant for bizarre and unreal images. As little Stan and Babe scamper beneath Laurel and Hardy’s big feet, one tends to wonder what strange conception has brought about this grotesque outcome. The original script called for a scene in which Big Hardy spanks little Stan over his knee, and Big Laurel punches little Babe in the chin, but this was too complex an effect to film. The entire thing appears as an over-elaborate metaphor of the idea of Stan and Ollie as children, the adults acting as childishly as the kids, the kids as painfully adult as their fathers. Delightful to some, to others it is an unsettling experience, more Dada than Daddy. On the plus side, we have a rare rendition of Oliver Hardy’s singing voice with the lullaby ‘Go to Sleep, My Baby’, the mellow timbres of a long-abandoned career. It is no wonder that Stan ruins this poignant moment the instant he joins in himself.

Stan and Ollie’s next film, Below Zero, featured the Depression in its full despondency. From its opening title – ‘The freezing winter of ’29 will long be remembered — Mr Hardy’s nose was so blue, Mr Laurel shot it for a jay-bird’ — this is perhaps the most melancholy and dark of all the boys’ duo films. A partial remake of episodes from You’re Darn Tootin’, it presents Stan and Ollie as street musicians in a most unconvincing snowstorm, Ollie on double-bass and Stan on harmonium. Their first effort to strum up business fails due to their setting up outside the obscured sign of the ‘Deaf and Dumb

Institute’, a gag Stan had been using from time immemorial, possibly dating as far back as Nuts in May. Removed to another location, Ollie’s soulful rendition of ‘She’s Your Tootsie-Wootsie in the Good Old Summertime’ earns him a snowball in the face from surly street cleaner Charlie Hall. A blind man goes by and then stops as he spots a dollar dropped in the road. A pigeon lays an egg in the outstretched tin mug. A hatchet-faced woman (played by Blanche Payson) breaks the bass over Ollie’s head and throws Stan’s instrument into the path of a steel-wheeled truck. To cap it all, the billfold of money they later find in the street turns out to belong to the neighbourhood cop they’ve invited to dine with them in the nearby steakhouse. The diner itself, in echoes of Chaplin’s seminal restaurant scene in The Immigrant —as well as a similar sequence from Stan’s early solo, Just Rambling Along —features the inevitable thuggish waiters who beat up customers who can’t pay.

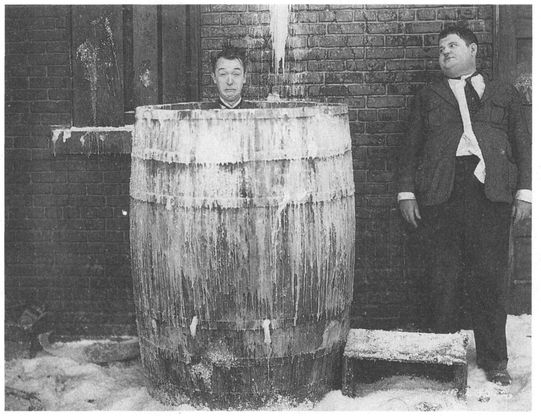

Below Zero — in the Depression dumps

Below Zero is almost impossible to laugh at, because Stan and Ollie’s humiliations derive not from their familiar characteristics or errors, but from the exigent social reality. When Ollie is beaten and thrown out, and Stan tossed by waiter Tiny Sandford into a barrel

of icy water, the ‘freezing winter of ’29’ becomes less of a joke and more of a cry of unrelieved pain. The climactic gag, that Stan has swallowed the water in the barrel, and waddles into the fade-out with a massive distended belly like today’s images of a malnourished child, can chill the blood, rather than tickle the funny bone. Once again, there are echoes of older films — of Jimmy Finlayson’s gas-bomb-distended belly in Stan’s Madame Mystery, floating above the ocean, but there is no albatross available to peck the stomach and send the afflicted man plunging back to earth.

Plunging back to earth does occur, repeatedly, in Hog Wild, the next Laurel and Hardy short, in which Mrs Hardy, Fay Holderness, makes Ollie go up on the roof to fix the radio aerial before he can be allowed to go out with Stan. (The main event occurring after an evocative domestic scene in which Ollie fumes about not finding his hat, which is on his head all the time, to the despair of his wife and the humiliating giggles of the maid.) Charles Barr quotes the famous critic Basil Wright’s contemporary comments:

In this film, the attempt to fix a wireless aerial on the roof of Hardy’s house precipitated Hardy off the roof into the goldfish pond at least five times. Each time, a different gag variation appeared, until the comedy passed into the realms of cutting, and the final fall was but a flight of birds and the sound of a mighty splash. Even Eisenstein would have been proud to do it.

High praise, and editor Richard Currier deserves all of it, despite the fact that the flight of birds is merely in the critic’s imagination. This was an occupational hazard, in recounting Laurel and Hardy films from memory, through the haze of laughter, and trying to disentangle one film from another.

Hog Wild is an excellent example of the maturity reached by Stan and Ollie’s comedy within just one year of their initiation into the talkie world. Although dialogue is central to the opening sequence of Ollie and his vanishing hat, the rest of the film relies almost solely on visual gags, give or take the inevitable crashes, crunches and cries as Ollie goes off the roof yet again. Unlike Liberty, in which the perils on the heights were of the surreal Lloyd-like school of spills and thrills, the balancing act on the slanted roof of the Hardy home is a comedy of everyday manners. Here the ritual of the pre-figured joke is at its most developed stage. From the moment Ollie, and then Stan, climb on the roof to fix the

aerial, the consequences are obvious, even to the most dimwitted child in the audience. Basil Wright may have been wrong about the birds, but the cutting — and the directing — ensure that, after Ollie’s (or his stunt man’s) first fall, there is no need to show those that follow, which are covered by the sounds of Ollie’s desperate moan, the crash, and the splash rising to the rooftop. Stan, for his part, stands helplessly above, the wholly innocent instrument of the Fall. Once on the ground, in the pond, or in a pile of bricks, or in the fireplace, the Fallen remains in place silently, the glance of mortification to the camera at its most eloquent, Ollie gathering strength for the next futile effort. Hog Wild is the perfect exemplar of a great Laurel and Hardy principle: if at first you don’t succeed, fail, fail again. Charles Barr, in discussing 1932’s The Music Box, defined this as an inversion of the principle of the western: the Hero has a set task to do, and succeeds against all odds. Laurel and Hardy have a set task to do, and they fail. And yet — they always climb back up the ladder again.

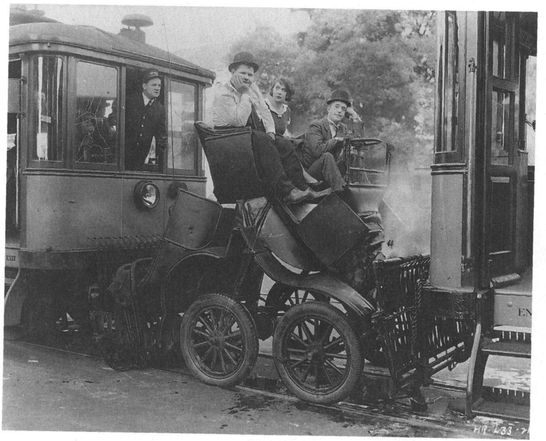

Modern transport in Hog Wild

For the climax of Hog Wild, Stan drives off with the ladder, with

Ollie still clinging to it, mounted on his car, into the busy Culver City traffic, tangling with streetcars before Ollie lands flat on his face. W. C. Fields was to present his own affectionate tribute to this kind of mad movie ride in his maternity hospital dash at the end of his last starring feature, Never Give a Sucker an Even Break, in 1941. But Hog Wild presents an exquisite topper, after Ollie’s wife has rushed up to cry on his shoulder, not because he has almost been killed but because the radio has been repossessed. Slumped exhausted in the car, as Stan vainly tries to start it, firing the exhaust and honking the horn for good measure, the three are struck by a tram rushing up behind the stalled vehicle, as passers-by, including the traffic cop, cover their eyes. Cut to the last shot of the film — the flivver concertinaed between two trams, and, like a reject from the traffic chaos of Two Tars, being driven off into the fade-out.

After the successful run of shorts, how to create a topper for Laurel and Hardy’s two- and three-reel hits? Hal Roach was reluctant to move from the world of shorts to comedy features. The two-reel format, he always declared, was the ideal length for a comedy idea. Stan, essentially, was in agreement — the old stalwart format of the vaudeville sketch was still the structure he was most attuned to. The days of the supporting short were not yet over, but the feature film, of course, provided a better income. Thus, after the lacklustre The Laurel—Hardy Murder Case, Stan and Ollie set to the production of their first feature-length film, Pardon Us, in the summer of 1930.

The story goes that the film, originally entitled ‘The Rap’, was planned as a short too, with Roach requesting MGM to allow him to shoot on the existing prison sets of their Wallace Beery jail saga, The Big House. MGM agreed on the proviso Roach loaned them Laurel and Hardy again, as in The Rogue Song, for their own uses, but Roach refused and built his own prison set, at such an expense that the only way to recoup it was to extend ‘The Rap’ to full length.

Whatever its origins, Pardon Us turned out to be a pot-pourri of recycled and previously unused ideas. Stan and Ollie are incompetent bootleggers who land in jail because Stan has sold a bottle of beer to a policeman, on the grounds that ‘I thought he was a streetcar conductor.’ Cue Ollie’s: ‘Well, here’s another nice mess you’ve gotten me into.’ Stan is in further trouble because of a chipped

tooth which makes him follow every sentence with what sounds like a deliberate raspberry, an unwise course when up against the warden, and then against Stan and Ollie’s most faithful heavy, plug-ugly convict Walter Long.

Confusion over Laurel and Hardy versions is particularly rife with regard to Pardon Us, which is listed variously as lasting 56, 61 and 63 minutes, the shortest being the extant US version and the longest existing in transmission of the British release. The latter includes an extended sequence of the boys’ mid-film escape from the prison, hiding out in blackface in a community of plantation workers, who seem to be living way back when in a happy-go-lucky, if indentured, state. All the versions include the long take in close-up of Ollie rendering the sentimental ditty: ‘Lazy moon, come out soon, make my poor heart be warmer … oh moon, don’t keep me waiting here tonight, longing for my little lady love …’ If Oliver Norvell Hardy ever sang with the minstrels, this is his heartfelt tribute. It is a poignant scene, ignored by many commentators, perhaps embarrassed by the unabashed racial patronizing of the entire episode.

The escape is foiled, when the warden and his daughter turn up in their car for a countryside jaunt and break down, calling on the two false cotton-pickers to assist them. Ollie’s blackface is licked off by a dog and Stan pulls out the chewing-gum he has been using to fix his tooth, emitting the tell-tale raspberry. In a previous scene, Stan, or director Jimmy Parrott, or both, pull off a bold ‘anti-cinematic’ coup when Stan and Ollie are locked in separate solitary cells after pelting prison teacher Jimmy Finlayson with ink. The camera remains static on the exterior of the two locked cell doors, in the corridor, for a full two minutes, while Stan and Ollie’s voices provide the following exchange from within:

STAN

Ollie, I wonder how long we’re going to be in here.

OLLIE

Oh, about two months, I guess.

STAN

(Pause for thought.) That’s a month apiece.

OLLIE

(Muttering) A month apiece! … You can take it from me, when I get out of here I’m going back on the farm. I can see it now — rows and rows of sweet corn swaying in the breezes, honey bees buzzing in the clover — and the smell of new-mown hay in the air.

STAN

Ollie.

OLLIE

What?

STAN

Did you say you can see all that?

OLLIE

Why, certainly.

STAN

That’s funny, I can’t see a thing, it’s dark in here.

The uneasy mixture of boldness and derivative scenes, in an episodic structure, will be characteristic of the Laurel and Hardy features as they struggle to fill the longer slots. Returned to jail after their escape, a few more minutes are gained by reprising the dentist scene from Leave ’Em Laughing — Ollie getting his tooth pulled by mistake and Stan having the wrong tooth taken, leaving him with his dangerous rasp. The climax is a standard prison riot, with Stan handed Walter Long’s hidden tommy-gun by mistake at the prison meal, leading to shots, mayhem, and the boys foiling the hard-core mutineers by sheer chance. Given their pardon by the warden for saving the day for law and order, they are told to start over where they left off. Prompting Stan’s logical query, ‘Can we take your order for a couple of cases?’, the panic run from the enraged warden, and fade-out.

Following Pardon Us, Stan and Ollie returned to the factory production of their short works. The first of these, Another Fine Mess, was a talkie remake of Duck Soup, based once again on the primal Arthur Jefferson Home from the Honeymoon sketch. The mad owner of the house they hide in as butler and maid this time is Jimmy Finlayson, as the aptly named Colonel Buckshot, pursuing

the two miscreants at the end as they escape dressed in a wildebeest skin, riding a tandem. Tangling with a streetcar in a tunnel, the bicycle and riders are shorn apart, each in his part of the skin, uni-cycling into The End.

The original writer of the sketch, back in Olde England, was not as charmed as most audiences by his son’s continued expropriation of his act. In an interview for the British magazine Picturegoer Weekly in 1932, in which he was posed in a bowler hat ‘to emphasize his likeness to his son’, Arthur Jefferson commented that ‘I sent him a little sketch of my own, which they filmed under the stupid title of Another Fine Mess, and I didn’t like the American angle they got on it one bit.’

Stan’s desertion of the home front to make his life and career in America clearly rankled with the elder Jefferson twenty years on. He talked about encouraging his son to ‘give us a little bit more of what England expects and a little less of what America expects … But’, the old man grudgingly accepted, ‘I think he is going to get the chance to give what he wants to give, from what I can hear.’

Stan had made one brief trip to England in 1927, to see his family, but he had not then been a famous or even a recognizable star. His next trip, with Babe Hardy, would be a very different affair. But it would have to await a gap in the schedule.

Be Big, Chickens Come Home and Laughing Gravy bridged the pass from 1930 into 1931. The latter was a remake of the silent Angora Love, with Stan and Ollie hiding a dog, instead of a goat, from landlord Charlie Hall. The film was intended to be a three-reeler, but was cut down on release to two reels. The original finale of the film, extant in the foreign versions, was replaced in the US with a short scene in which, after the landlord’s desperate attempt to catch them with the dog, ‘Laughing Gravy’, and evict them, a policeman arrives with a quarantine notice that says no one can leave the house for two months. Charlie exits and two shots are heard off screen. Stan, Ollie and cop doff their hats. But the replaced scene, restored from an unreleased English-language copy for the recent video re-release of the film, turns out to be a mint centrepiece of the fundamental Laurel and Hardy relationship. In this version, after the landlord has ordered them to quit the house, the boys pack in their room, Ollie muttering angrily to himself.

In bed with ‘Laughing Gravy’

STAN

What’s the matter?

OLLIE

What’s the matter? You’re the cause of me being in this deplorable condition. You’ve held me back for years and I’m sick of it.

They continue packing. Knock on the door, and landlord Charlie delivers Stan a letter, which says that he is ‘the sole heir to your late Uncle’s fortune — providing you sever all connections with OLIVER HARDY, whom your Uncle felt is responsible for your deplorable condition’.

(Looking worried, then smiles) What’s that?

STAN

A letter.

OLLIE

Who is it from?

STAN

A friend.

OLLIE

What’s it about?

STAN

It’s about me.

OLLIE

Is it good news or bad news?

STAN

Yes and no.

OLLIE

What do you mean, ‘yes and no’?

STAN

Well, ’tis, and ’tisn’t … ’tisn’t and ’tis …

OLLIE

You’re getting on my nerves. Let me see that letter.

STAN

It’s private.

OLLIE

(Goes into a fuming sulk.) Well, if it’s private it’s private … Thank goodness it’s not in my nature to hold out anything on a pal … Once a friend always a friend. It’s fifty—fifty with a Hardy. But then, it takes all sorts of people to make a world. It’s all right. Don’t worry, I won’t complain. (Turns away, packing his shirt collars, chanting:) You’ll be sorry just too late, when our friendship turns to hate, when our friendship turns to hate, you’ll be sorry just too late …

Stan, worn down, flustered, turns and holds out the letter to Ollie.

What? Me read your letter? I should say not! … No Hardy would read anyone’s personal mail …

STAN

(Turning away) All right.

OLLIE

(Grabbing the letter) Oh, give me that letter! (Begins reading, sees check.) Oh, holding out on me! ’Twas ever thus … (Reads on, glances with a terrible guilt at the camera. His face softens as he turns to Stan.) Now I know why you didn’t want me to read it. I’m sorry of everything I said.

And I thought all the time it was you holding me back. Isn’t it funny. We never see ourselves as others see us. Well, you’d better be going.

STAN

(Tearful) What’s going to become of you?

OLLIE

Oh, don’t worry about me. I’ll be all right. Goodbye.

STAN

Bye.

OLLIE

And good luck.

Stan exits frame, goes to pick up suitcase and the dog, ‘Laughing Gravy’. Ollie steps up to him and takes the dog.

You’re not going to strip me of everything, aren’t you? It’s going to be lonesome enough without you taking the dog. Goodbye.

STAN

Bye.

He turns. Ollie glances at us, with dog. Stan puts down his case, turns, tears the letter and check to shreds.

OLLIE

(Beaming) My pal! And to think you’re giving it all up for me!

STAN

(Nods, then double take.) For you? I didn’t want to leave Laughing Gravy.

Stan takes dog from Ollie. Ollie goes berserk, begins smashing everything in sight. Fade-out.

Hidden from English-speaking fans for over fifty years, this scene has a resonance that goes far beyond our two heroes. The simple, tit-for-tat dialogue, in its deliberate slowness and its monosyllabic cadences, looks forward to the kind of dialogue modernist playwrights, such as Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett, derived from the rhythms of ordinary, banal talk. In a later period, when serious writers examined the way people hide their thoughts behind their speech, some of the most influential voices of our time harked

back to the formulations of music-hall. Grimaldi and Dan Leno’s famous comic observations of everyday life and parlance echo into the present age. The Marx Brothers, and W. C. Fields, played with language, turned it about, stood it on its head, extracted all manners of unexpected, hidden meanings. But Stan and Ollie are completely devoid of subterfuge, on the one hand, and consumed with self-deception, on the other. They have the capacity to misunderstand the simplest things that human beings take for granted. Like an old married couple, they are locked into a ‘co-dependency’ in which each is the mirror image of the other. They may come from different ends of the earth, they may be ground down by misfortune, they may be physical, even temperamental opposites, but they partake in the purest form of the human principle that no man — or woman — is an island. We complement each other, a part of the whole. This, of course, may only be a dream, an aspiration, but everything is a dream — in the movies.