CHAPTER

Seven

When you know someone a long time, you become accustomed to their idiosyncrasies, which is a fancy word for their unique habits. For instance, Sunny Baudelaire had known her sister, Violet, for quite some time, and was accustomed to Violet’s idiosyncrasy of tying her hair up in a ribbon to keep it out of her eyes whenever she was inventing something. Violet had known Sunny for exactly the same length of time, and was accustomed to Sunny’s idiosyncrasy of saying “Freijip?” when she wanted to ask the question “How can you think of elevators at a time like this?” And both the young Baudelaire women were very well acquainted with their brother, Klaus, and were accustomed to his idiosyncrasy of not paying a bit of attention to his surroundings when he was thinking very hard about something, as he was clearly doing as the afternoon wore on.

The doorman continued to insist that the Baudelaire orphans could not return to the penthouse, so the three children sat on the bottom step of 667 Dark Avenue’s lengthy stairwell, ate food they had brought down with them, and rested their weary legs, which had not felt this sore since Olaf, in a previous disguise, had forced them to run hundreds and hundreds of laps as part of his scheme to steal their fortune. A good thing to do when one is sitting, eating, and resting is to have a conversation, and Violet and Sunny were both eager to converse about Gunther’s mysterious appearance and disappearance, and what they might be able to do about it, but Klaus scarcely participated in the discussion. Only when his sisters asked him a direct question, such as “But where in the world could Gunther be?” or “What do you think Gunther is planning?” or “Topoing?” did Klaus mumble a response, and Violet and Sunny soon figured out that Klaus must be thinking very hard about something, so they left him to his idiosyncrasy and talked quietly to each other until the doorman ushered Jerome and Esmé into the lobby.

“Hello, Jerome,” Violet said. “Hello, Esmé.”

“Tretchev!” Sunny shrieked, which meant “Welcome home!”

Klaus mumbled something.

“What a pleasant surprise to see you all the way down here!” Jerome said. “It’ll be easier to climb all those stairs if we have you three charming people for company.”

“And you can carry the crates of parsley soda that are stacked outside,” Esmé said. “Then I don’t have to worry about breaking one of my fingernails.”

“We’d be happy to carry big crates up all those stairs,” Violet lied, “but the doorman says we’re not allowed back in the penthouse.”

“Not allowed?” Jerome frowned. “Whatever do you mean?”

“You gave me specific instructions not to let the children back in, Mrs. Squalor,” the doorman said. “At least, until Gunther left the building. And he still hasn’t left.”

“Don’t be absurd,” Esmé said. “He left the penthouse last night. What kind of doorman are you?”

“Actually, I’m an actor,” the doorman said, “but I was still able to follow your instructions.”

Esmé gave the doorman a stern look she probably used when giving people financial advice. “Your instructions have changed,” she said. “Your new instructions are to let me and my orphans go directly to my seventy-one-bedroom apartment. Got it, buster?”

“Got it,” the doorman replied meekly.

“Good,” Esmé said, and then turned to the children. “Hurry up, kids,” she said. “Violet and what’s-his-name can each take a crate of soda, and Jerome will take the rest. I guess the baby won’t be very helpful, but that’s to be expected. Let’s get a move on.”

The Baudelaires got a move on, and in a few moments the three children and the two adults were trekking up the sixty-six-floor-long staircase. The youngsters were hoping that Esmé might help carry the heavy crates of soda, but the city’s sixth most important financial advisor was much more interested in telling them all about her meeting with the King of Arizona than in buttering up any orphans. “He told me a long list of new things that are in,” Esmé squealed. “For one thing, grapefruits. Also bright blue cereal bowls, billboards with photographs of weasels on them, and plenty of other things that I will list for you right now.” All the way up to the penthouse, Esmé listed the new in items she had learned about from His Arizona Highness, and the two Baudelaire sisters listened carefully the whole time. They did not listen very carefully to Esmé’s very dull speech, of course, but they listened closely at each curve of the staircase, double-checking their eavesdropping to hear if Gunther was indeed behind one of the apartment doors. Neither Violet nor Sunny heard anything suspicious, and they would have asked Klaus, in a low whisper so the Squalors couldn’t hear them, if he had heard any sort of Gunther noise, but they could tell from his idiosyncrasy that he was still thinking very hard about something and wasn’t listening to the noises in the other apartments any more than he was listening to automobile tires, cross-country skiing, movies with waterfalls in them, and the rest of the in things Esmé was rattling off.

“Oh, and magenta wallpaper!” Esmé said, as the Baudelaires and the Squalors finished a dinner of in foods washed down with parsley soda, which tasted even nastier than it sounds. “And triangular picture frames, and very fancy doilies, and garbage cans with letters of the alphabet stenciled all over them, and—”

“Excuse me,” Klaus said, and his sisters jumped a little bit in surprise. It was the first time Klaus had spoken in anything but a mumble since they had been down in the lobby. “I don’t mean to interrupt, but my sisters and I are very tired. May we be excused to go to bed?”

“Of course,” Jerome said. “You should get plenty of rest for the auction tomorrow. I’ll take you to the Veblen Hall at ten-thirty sharp, so—”

“No you won’t,” Esmé said. “Yellow paper clips are in, Jerome, so as soon as the sun rises, you’ll have to go right to the Stationery District and get some. I’ll bring the children.”

“Well, I don’t want to argue,” Jerome said, shrugging and giving the children a small smile. “Esmé, don’t you want to tuck the children in?”

“Nope,” Esmé answered, frowning as she sipped her parsley soda. “Folding blankets over three wriggling children sounds like a lot more trouble than it’s worth. See you tomorrow, kids.”

“I hope so,” Violet said, and yawned. She knew that Klaus was asking to be excused so he could tell her and Sunny what he had been thinking about, but after lying awake the previous night, searching the entire penthouse, and tiptoeing down all those stairs, the eldest Baudelaire was actually quite tired. “Good night, Esmé. Good night, Jerome.”

“Good night, children,” Jerome said. “And please, if you get up in the middle of the night and have a snack, try not to spill your food. There seem to be a lot of crumbs around the penthouse lately.”

The Baudelaire orphans looked at one another and smiled at their shared secret. “Sorry about that,” Violet said. “Tomorrow we’ll do the vacuuming if you want.”

“Vacuum cleaners!” Esmé said. “I knew there was something else he told me was in. Oh, and cotton balls, and anything with chocolate sprinkles on it, and . . .”

The Baudelaires did not want to stick around for any more of Esmé’s in list, so they brought their plates into the nearest kitchen, and walked down a hallway decorated with the antlers of various animals, through a sitting room, past five bathrooms, took a left at another kitchen, and eventually made their way to Violet’s bedroom.

“O.K., Klaus,” Violet said to her brother, when the three children had found a comfortable corner for their discussion. “I know you’ve been thinking very hard about something, because you’ve been doing that unique habit of yours where you don’t pay a bit of attention to your surroundings.”

“Unique habits like that are called idiosyncrasies,” Klaus said.

“Stiblo!” Sunny cried, which meant “We can improve our vocabulary later—tell us what’s on your mind!”

“Sorry, Sunny,” Klaus said. “It’s just that I think I’ve figured out where Gunther might be hiding, but I’m not positive. First, Violet, I need to ask you something. What do you know about elevators?”

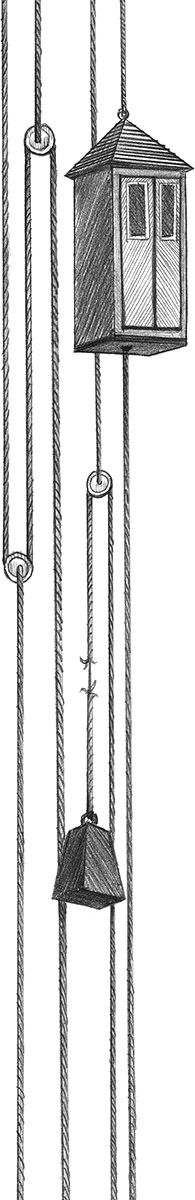

“Elevators?” Violet said. “Quite a bit, actually. My friend Ben once gave me some elevator blueprints for my birthday, and I studied them very closely. They were destroyed in the fire, of course, but I remember that an elevator is essentially a platform, surrounded by an enclosure, that moves along the vertical axis via an endlessly looped belt and a series of ropes. It’s controlled by a push-button console that regulates an electromagnetic braking system so the transport sequence can be halted at any access point the passenger desires. In other words, it’s a box that moves up or down, depending on where you want to go. But so what?”

“Freijip?” Sunny asked, which, as you know, was her idiosyncratic way of saying “How can you think of elevators at a time like this?”

“Well, it was the doorman who got me thinking about elevators,” Klaus said. “Remember when he said that sometimes the solution is right under your nose? Well, he was gluing that wooden starfish to the elevator doors right when he said that.”

“I noticed that, too,” Violet said. “It looked a little ugly.”

“It did look ugly,” Klaus agreed. “But that’s not what I mean. I got to thinking about the elevator doors. Outside the door to this penthouse, there are two pairs of elevator doors. But on every other floor, there’s only one pair.”

“That’s true,” Violet said, “and that’s odd, too, now that I think of it. That means one elevator can stop only on the top floor.”

“Yelliverc!” Sunny said, which meant “That second elevator is almost completely useless!”

“I don’t think it’s useless,” Klaus said, “because I don’t think the elevator is really there.”

“Not really there?” Violet asked. “But that would just leave an empty elevator shaft!”

“Middiow?” Sunny asked.

“An elevator shaft is the path an elevator uses to move up and down,” Violet explained to her sister. “It’s sort of like a hallway, except it goes up and down, instead of side to side.”

“And a hallway,” Klaus said, “could lead to a hiding place.”

“Aha!” Sunny cried.

“Aha is right,” Klaus agreed. “Just think, if he used an empty elevator shaft instead of the stairs, nobody would ever know where he was. I don’t think the elevator has been shut down because it’s out. I think it’s where Gunther is hiding.”

“But why is he hiding? What is he up to?” Violet asked.

“That’s the part we still don’t know,” Klaus admitted, “but I bet you the answers can be found behind those sliding doors. Let’s take a look at what’s behind the second pair of elevator doors. If we see the ropes and things you were describing, then we know it’s a real elevator. But if we don’t—”

“Then we know we’re on the right track,” Violet finished for him. “Let’s go right this minute.”

“If we go right this minute,” Klaus said, “we’ll have do it very quietly. The Squalors are not going to let three children poke around an elevator shaft.”

“It’s worth the risk, if it helps us figure out Gunther’s plan,” Violet said. I’m sorry to say that it turned out not to be worth the risk at all, but of course the Baudelaires had no way of knowing that, so they merely nodded in agreement and tiptoed toward the penthouse’s exit, peeking into each room before they went through to see if the Squalors were anywhere to be found. But Jerome and Esmé were apparently spending the evening in some room in another part of the apartment, because the Baudelaires didn’t see hide or hair of them—the expression “hide or hair of them” here means “even a glimpse of the city’s sixth most important financial advisor, or her husband”—on their way to the front door. They hoped the door would not squeak as they pushed it open, but apparently silent hinges were in, because the Baudelaires made no noise at all as they left the apartment and tiptoed over to the two pairs of sliding elevator doors.

“How do we know which elevator is which?” Violet whispered. “The pairs of doors look exactly alike.”

“I hadn’t thought of that,” Klaus replied. “If one of them is really a secret passageway, there must be some way to tell.”

Sunny tugged on the legs of her siblings’ pants, which was a good way to get their attention without making any noise, and when Violet and Klaus looked down to see what their sister wanted, she answered them just as silently. Without speaking, she reached out one of her tiny fingers and pointed to the buttons that were next to each set of sliding doors. Next to one pair of doors, there was a single button, with an arrow printed on it pointing down. But next to the second pair of doors, there were two buttons: one with a Down arrow, and one with an Up arrow. The three children looked at the buttons and considered.

“Why would you need an Up button,” Violet whispered, “if you were already on the top floor?” and without waiting for an answer to her question, she reached out and pressed it. With a quiet, slithery sound, the sliding doors opened, and the children leaned carefully into the doorway, and gasped at what they saw.

“Lakry,” Sunny said, which meant something like “There are no ropes.”

“Not only are there no ropes,” Violet said. “There’s no endlessly looped belt, push-button console, or electromagnetic braking system. I don’t even see an enclosed platform.”

“I knew it,” Klaus said, in hushed excitement. “I knew the elevator was ersatz!”

“Ersatz” is a word that describes a situation in which one thing is pretending to be another, the way the secret passageway the Baudelaires were looking at had been pretending to be an elevator, but the word might as well have meant “the most terrifying place the Baudelaires had ever seen.” As the children stood in the doorway and peered into the elevator shaft, it was as if they were standing on the edge of an enormous cliff, looking down at the dizzying depths below them. But what made these depths terrifying, as well as dizzying, was that they were so very dark. The shaft was more like a pit than a passageway, leading straight down into a blackness the likes of which the youngsters had never seen. It was darker than any night had ever been, even on nights when there was no moon. It was darker than Dark Avenue had been on the day of their arrival. It was darker than a pitch-black panther, covered in tar, eating black licorice at the very bottom of the deepest part of the Black Sea. The Baudelaire orphans had never dreamed that anything could be this dark, even in their scariest nightmares, and as they stood at the edge of this pit of unimaginable blackness, they felt as if the elevator shaft would simply swallow them up and they would never see a speck of light again.

“We have to go down there,” Violet said, scarcely believing the words she was saying.

“I’m not sure I have the courage to go down there,” Klaus said. “Look how dark it is. It’s terrifying.”

“Prollit,” Sunny said, which meant “But not as terrifying as what Gunther will do to us, if we don’t find out his plan.”

“Why don’t we just go tell the Squalors about this?” Klaus asked. “Then they can go down the secret passageway.”

“We don’t have time to argue with the Squalors,” Violet said. “Every minute we waste is a minute the Quagmires are spending in Gunther’s clutches.”

“But how are we going to go down?” Klaus asked. “I don’t see a ladder, or a staircase. I don’t see anything at all.”

“We’re going to have to climb down,” Violet said, “on a rope. But where can we find rope at this time of night? Most hardware stores close at six.”

“The Squalors must have some rope somewhere in their penthouse,” Klaus said. “Let’s split up and find some. We’ll meet back here in fifteen minutes.”

Violet and Sunny agreed, and the Baudelaires stepped carefully away from the elevator shaft and tiptoed back into the Squalor penthouse. They felt like burglars as they split up and began searching the apartment, although there have been only five burglars in the history of robbery who have specialized in rope. All five of these burglars were caught and sent to prison, which is why scarcely any people lock up their rope for safekeeping, but to their frustration, the Baudelaires learned that their guardians didn’t lock up their ropes at all, for the simple reason that they didn’t have any.

“I couldn’t find any ropes at all,” Violet admitted, as she rejoined her siblings. “But I did find these extension cords, which might work.”

“I took these curtain pulls down from some of the windows,” Klaus said. “They’re a little bit like ropes, so I thought they might be useful.”

“Armani,” Sunny offered, holding up an armful of Jerome’s neckties.

“Well, we have some ersatz ropes,” Violet said, “for our climb down the ersatz elevator. Let’s tie them all together with the Devil’s Tongue.”

“The Devil’s Tongue?” Klaus asked.

“It’s a knot,” Violet explained. “It was invented by female Finnish pirates in the fifteenth century. I used it to make my grappling hook, when Olaf had Sunny trapped in that cage, dangling from his tower room, and it’ll work here as well. We need to make as long a rope as possible—for all we know, the passageway goes all the way to the bottom floor of the building.”

“It looks like it goes all the way to the center of the earth,” Klaus said. “We’ve spent so much of our time trying to escape from Count Olaf. I can’t believe that now we’re trying to find him.”

“Me neither,” Violet agreed. “If it weren’t for the Quagmires, I wouldn’t go down there at all.”

“Bangemp,” Sunny reminded her siblings. She meant something along the lines of “If it weren’t for the Quagmires, we would have been in his clutches a long time ago,” and the two older Baudelaires nodded in agreement. Violet showed her siblings how to make the Devil’s Tongue, and the three children hurriedly tied the extension cords to the curtain pulls, and the curtain pulls to the neckties, and the last necktie to the sturdiest thing they could find, which was the doorknob of the Squalor penthouse. Violet checked her siblings’ handiwork and finally gave the whole rope a satisfied tug.

“I think this should hold us,” she said. “I only hope it’s long enough.”

“Why don’t we drop the rope down the shaft,” Klaus said, “and listen to see if it hits the bottom? Then we’ll know for sure.”

“Good idea,” Violet replied, and walked to the edge of the passageway. She threw down the edge of the furthermost extension cord, and the children watched as it disappeared into the blackness, dragging the rest of the Baudelaires’ line with it. The coils of cord and pull and necktie unwound quickly, like a long snake waking up and slithering down into the shaft. It slithered and slithered and slithered, and the children leaned forward as far as they dared and listened as hard as they could. Finally, they heard a faint, faint clink!, as if the extension cord had hit a piece of metal, and the three orphans looked at one another. The thought of climbing down all that distance in the dark, on an ersatz rope they had fashioned themselves, made them want to turn around and run all the way back to their beds and pull the blankets over their heads. The siblings stood together at the edge of this dark and terrible place and wondered if they really dared to begin the climb. The Baudelaire rope had made it to the bottom. But would the Baudelaire children?

“Are you ready?” Klaus asked finally.

“No,” Sunny answered.

“Me neither,” Violet said, “but if we wait until we’re ready we’ll be waiting for the rest of our lives. Let’s go.”

Violet tugged one last time on the rope, and carefully, carefully lowered herself down the passageway. Klaus and Sunny watched her disappear into the darkness as if some huge, hungry creature had eaten her up. “Come on,” they heard her whisper, from the blackness. “It’s O.K.”

Klaus blew on his hands, and Sunny blew on hers, and the two younger Baudelaires followed their sister into the utter darkness of the elevator shaft, only to discover that Violet had not told the truth. It was not O.K. It was not half O.K. It was not even one twenty-seventh O.K. The climb down the shadowy passageway felt like falling into a deep hole at the bottom of a deep pit on the bottom floor of a dungeon that was deep underground, and it was the least O.K. situation the Baudelaires had ever encountered. Their hands gripping the line was the only thing they saw, because even as their eyes adjusted to the darkness, they were afraid to look anywhere else, particularly down. The distant clink! at the bottom of the line was the only sound they heard, because the Baudelaires were too scared to speak. And the only thing they felt was sheer terror, as deep and as dark as the passageway itself, a terror so profound that I have slept with four night-lights ever since I visited 667 Dark Avenue and saw this deep pit that the Baudelaires climbed down. But I also saw, during my visit, what the Baudelaire orphans saw when they reached the bottom after climbing for more than three terrifying hours. By then, their eyes had adjusted to the darkness, and they could see what the bottom of their line was hitting, when it was making that faint clinking sound. The edge of the farthest extension cord was bumping up against a piece of metal, all right—a metal lock. The lock was secured around a metal door, and the metal door was attached to a series of metal bars that made up a rusty metal cage. By the time my research led me to this passageway, the cage was empty, and had been empty for a very long time. But it was not empty when the Baudelaires reached it. As they arrived at the bottom of this deep and terrifying place, the Baudelaire orphans looked into the cage and saw the huddled and trembling figures of Duncan and Isadora Quagmire.