The original 20TS prototype (the predecessor of the TR2) was previewed in October 1952, and had a short tail with an exposed spare wheel.

FROM THE TR2 TO THE TR6

BY AUTUMN 1953, when the TR2 sports car finally staggered into production, Triumph needed another success. The miracle was that the TR2 then did so much for Triumph’s reputation, for its original concept was all wrong. Jealous of MG’s progress in North America, and frustrated by his failure to annex Morgan, Sir John Black imposed impossible cost and time constraints on his team, and demanded that a new sports car – the ‘20TS’ – be readied in 1952. Apparently, he was willing to consider Morgan-scale production of only ten cars a week. But, with MG already building 200 TDs every week, it was unlikely that this approach would reap great rewards.

The very first 20TS prototype was a real mix-and-match concoction. Built on a modified 1936-style Standard Flying Nine chassis frame, with Mayflower front suspension, a modified Standard Vanguard engine and a four-speed gearbox, it was given a sturdy new two-seater body style with an exposed spare wheel on a short tail.

The original 20TS prototype (the predecessor of the TR2) was previewed in October 1952, and had a short tail with an exposed spare wheel.

In three months the design team then produced a new chassis frame along with a developed engine which produced 90 bhp; the body style was improved; and endless development testing work eventually resulted in the definitive TR2. Finally going into production in the autumn of 1953, it then had to prove itself in the marketplace. Production built up rapidly in 1954, when 4,891 TR2s were produced, and when the TR2 made its name in two ways – one by a remarkable series of road tests, the other by its burgeoning rallying record.

Everyone, no doubt, was expecting a top speed of 104 mph and 0–60 mph in 11.9 seconds – but no-one thought such a car could achieve 32 mpg overall, and sometimes even better than that. This, incidentally, was recorded with a non-overdrive car, so with that option fitted the fuel efficiency became even more pronounced. Not only was this a quick car, but it soon proved itself to be rock solid.

When Johnny Wallwork won the RAC International rally outright in March 1954 in his own privately prepared TR2, the motoring world sat up and took notice, especially as TR2s also finished second, fifth and helped Mary Walker win the Ladies’ Prize. Two months later the Gatsonides/ Richardson TR2 finished the Mille Miglia; four weeks after that the Wadsworth/ Dickson car performed creditably at Le Mans; and shortly a team of ‘works’ TR2s made a quite remarkable debut in the French Alpine rally.

This was the very first right-hand-drive TR2 in production form; carrying the Commission Number TS2, it is now preserved by the Triumph TR Register. The rear wheel covers were optional extras and rarely fitted.

By the mid-1950s the entire atmosphere at Canley had been transformed. After more than twenty years at the helm, in 1954 Sir John Black was ousted as managing director, and his successor, Alick Dick, was a much more sunny, outgoing, and forward-thinking character. Dour old hands like technical director Ted Grinham were eased gently into retirement; younger personalities like Harry Webster, John Turnbull and Martin Tustin came onto the scene; and the public’s perception of Standard-Triumph was suddenly of a bubbly, thrusting, sporting-minded business.

Much of the development work but none of the actual design of the TR2 was carried out by Ken Richardson, who posed for this picture in the autumn of 1953.

The ‘sidescreen’ TRs – their character and their abilities – had a lot to do with that image change. All over the world, it seemed, enthusiasts flocked to buy TRs, for racing and rallying, and certainly for open-air enjoyment. There’s no doubt that many of those enthusiasts deserted MG to move over to Triumph, for which MG fanatics never forgave Triumph.

As every TR enthusiast surely knows, the last ‘sidescreen’ TR of all, the TR3B of 1962, made solely for the American market, was still broadly the same car as that which had started life nine years earlier. Even so, in that time almost every mechanical detail had been changed, updated or improved at least once.

The TR3 replaced the TR2 for 1956, with relatively minor changes, including more power and an ‘egg-box’ grille. Front-wheel disc brakes were standardised from the autumn of 1956. The TR3A, complete with new front-end style and full-width ‘dollar grin’, went into production in the autumn of 1957, by which time TR-mania was at its height in the USA. Triumph then made the mistake of overproducing in 1960, necessitating a slowing of production at the end of that year – almost every USA sale of 1961 was made from existing dealer stocks, or from cars already being shipped stateside.

The TR2 became TR3 in the autumn of 1955, with updates which included a new type of ‘egg-box’ front grille. Wire-spoke wheels were optional extras.

Finally came the TR3B of 1962, never in Triumph’s marketing masterplan, but only built after the American dealers complained that the new TR4 was too different, too soon, and could they please have more of the old cars? For one season only, Standard-Triumph therefore built 3,331 TR3Bs, some with 2.0-litre, some with 2.2-litre engines, and all with TR4-type all-synchromesh gearboxes. They did not, however, have the wide-track suspension, nor the rack-and-pinion steering of the new-type TR4.

From 1956 Alick Dick authorised work on a new body style for the TR sports car, but the chief body engineer Walter Belgrove had now left the company, and his other stylists were short of inspiration. Vic Hammond’s team eventually produced a variety of shapes which evolved into smooth machines with more than a hint of the latest Ferrari around the nose. At the same time, they made several attempts to give the TR3 a facelift.

As we now know, there was much still to be settled when the Italian stylist, Giovanni Michelotti, came on the scene. His first style on a TR3 chassis was the black and white ‘dream car’ of 1957, which was never intended for production, but made everyone sit up and think.

For the next three years company policy seemed chaotic. There were no firm decisions on what the ‘new TR4’ should look like; potential features included a 6-inch longer wheelbase, widened wheel tracks, a 2-litre six-cylinder engine, and the option of a detuned Le Mans-type twin-cam engine – or any combination of those items. To make sense out of all this, Harry Webster sent Ray Bates and a small team away from mainstream engineering to think again, and it was they who developed many important elements of the TR4, such as its wide-track chassis and rack-and-pinion steering.

The first Michelotti ‘Zest’ of 1958 was narrow, with a Herald Coupé roof; the ‘Zoom’ of 1959 had different styling and a longer wheelbase (both were used in the 1960/1961 Le Mans cars, which had glass-fibre bodies), but the definitive ‘Zest’ of 1960/1961 was a widened car on the standard wheelbase, with the familiar 2.2-litre wet-liner engine – in other words, the TR4 as we know it.

This study of three cars shows a TR3 in the background, a wide-grilled TR3A in the centre of the shot, and a view of the rear-end style which did not change from 1953 to 1962.

In 1961 Triumph dabbled with the idea of using the new-for-TR4 chassis, complete with wider front and rear tracks, with a modified type of TR3A bodyshell, and would have called the product TR3 Beta, but it was never put on sale.

Several hundred smart Italia coupés were produced by Vignale in Italy, using rolling chassis supplied from the UK and with a Michelotti-styled body.

The original Michelotti-styled TR sports car was the TR4, which appeared in 1961, and included such marketing novelties as wind-up door windows, face-level ventilation and the availability (as an option) of a two-piece lift-off hardtop.

This had gone on too long, for by 1961 the company was in financial trouble. Demand for the TR3A had dramatically declined in 1960, and very few TR3As were made in 1961. Fortunately Standard-Triumph Liverpool (not Mulliners, who had built earlier TRs) rushed through the tooling for the new style, and the first new-style cars were delivered in September 1961.

The first so-called ‘Michelotti TR’ – the 2.2-litre TR4 – was mechanically familiar, but bodily bold. Wider tracks and new steering, plus an all-synchromesh gearbox, were all new, there was the little-advertised option of the old-type 2.0-litre engine, and the new body included features such as face-level ventilation and an optional lift-off steel roof panel (Porsche would call it the ‘Targa’ top) – which others would wrongly claim as their own.

Between 1961 and 1969, when the TR6 arrived, the design of the TR4 changed gradually, persistently and completely, though the internal body structure and the general proportions were not altered. Early in 1965 the TR4A replaced the TR4, with a brand-new chassis, semi-trailing arm independent rear suspension similar to that of the new 2000 saloon and with a 104-bhp version of the 2.2-litre engine. A 2.5-litre version of the engine had also been tested, as had automatic transmission, but both were cancelled – and as an option in North America there was a rigid rear axle instead of the newfangled IRS, though this was mated to the new-type frame.

During the life of the TR4 a Triumph dealer, Doves of Wimbledon, promoted this TR4 Dove sports hatchback, which was mechanically the same as the TR4, but heavier and more commodious.

In 1954 and 1955 Triumph supplied TR2 running gear to Swallow, of the West Midlands, for that company to produce the Doretti, an extremely smart, but expensive, two-seater sports car.

Two and a half years later the TR4A was gone too, for there was no future for the old ‘wet-liner’ four-cylinder engine, which was therefore replaced by a smooth 2.5-litre long-stroke version of the 2000’s straight-six. Originally, Harry Webster’s engineers had chosen Lucas fuel injection to gain power and meet new exhaust emission rules, but had then found that the system could not meet the emission limits after all. Therefore, for North America a Zenith-Stromberg carburetted engine was used, with injected PI (Petrol Injection) models being built for the rest of the world. North American cars were TR250s, complete with speed stripes across the bonnet and front wings, other types being TR5s.

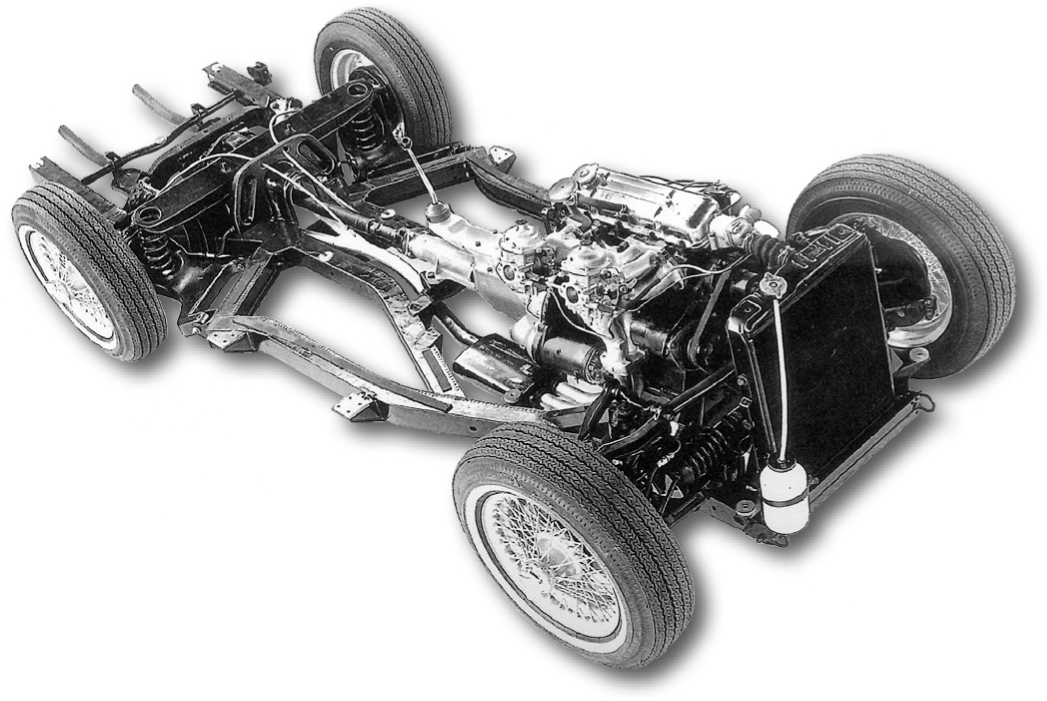

For the TR4A of 1965, Triumph produced a completely new chassis frame, which used coil spring independent rear suspension based on that of the 2000 saloon. For sale only in the USA, there was also a beam-rear-axle version of this frame, which sold at a lower price.

Announced in 1961, the TR4 was the first of the Michelotti-styledTRs. As later followed by the TR4A, the TR250, TR5 and TR6 models, these were the best-selling Triumph sports cars for the next fifteen years.

By then, though, the next phase of TR development was under way. Triumph would have liked to have given the model a facelift when the six-cylinder appeared, but styling and tooling facilities were overloaded at that time. Soon afterwards, Karmann of Germany – who later built Golf Cabriolets, Escort Cabriolets, Escort RS Cosworths and operated an efficient body tooling facility – came looking for business, got it and ended up with a contract to restyle and to retool the TR.

The result was the TR6, which went into production in the autumn of 1968, and was revealed in January 1969. Beneath the surface all was familiar, but there was a new nose, a new tail – both features being more angular than before – and a new-style optional one-piece hardtop. This time the North American version was also called TR6, though the detuned engine remained.

With regular cosmetic improvements, the TR6 then carried on for seven years, outliving British Leyland’s independent period (which ended in January 1975) and even being built during the eighteen months after the TR7 was revealed. The last TR6 to be produced left the factory in mid-1976.

The Fury of 1965 was a one-off prototype with a unit-construction bodyshell and a six-cylinder 2000 type of engine. It was very smart and very nimble, but the tooling costs would have been too high for it ever to have been profitable. Only one such car was built.

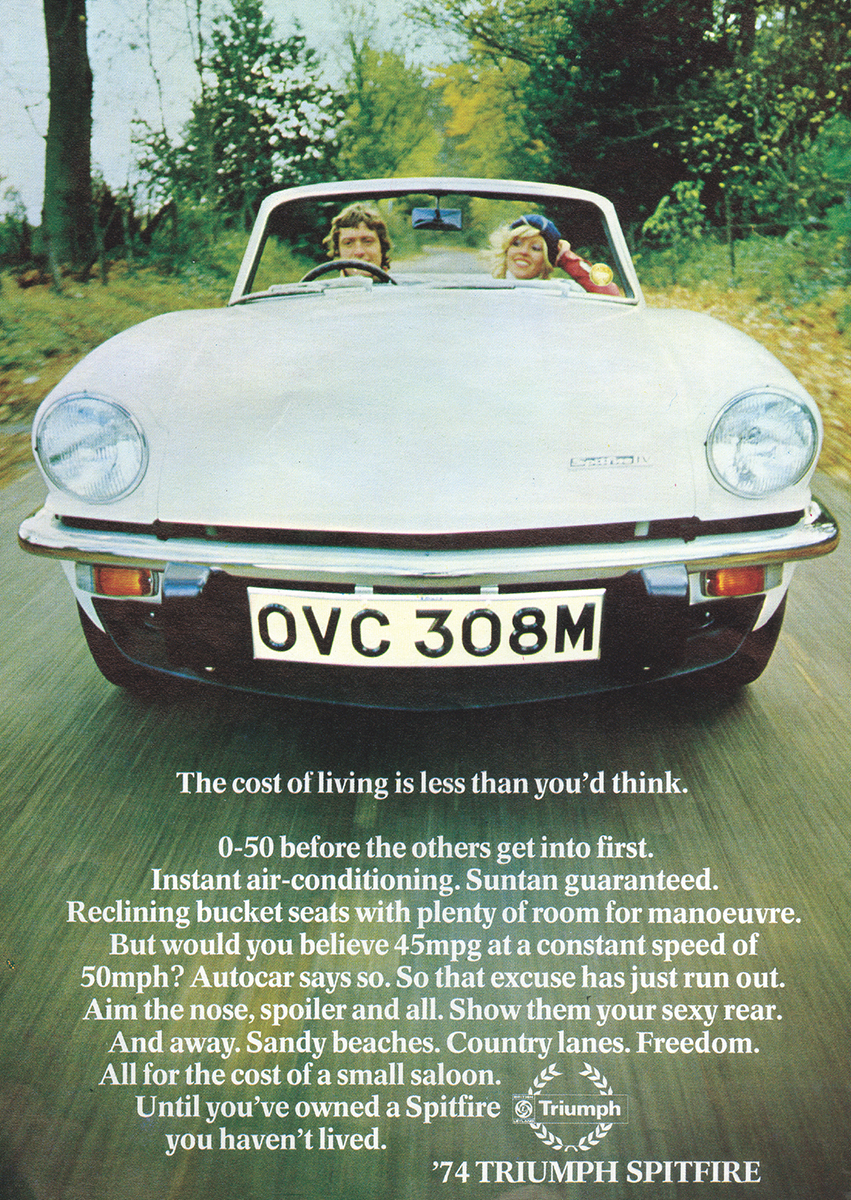

From 1970 the Spitfire’s front-end was restyled to have a more carefully integrated bumper and bonnet. This was British Leyland’s proud advertising of the early 1970s.