H

Henri de Mondeville

Henri de Mondeville (c. 1260–1320) was a Norman surgeon, professor, and author who studied medicine and surgery at the universities of Paris and Montpellier. He claimed as his master Jean Pitard, who was court physician and battlefield surgeon to King Philip the Fair. Through his association with Pitard, Mondeville obtained a medical position in service to the king, and by 1301 was both a court physician and an army surgeon. He continued to serve in the same capacity Philip’s successors, Charles of Valois, and Louis X. Mondeville also taught at the university, and by 1304 he was a lecturer at Montpellier in both medicine and *surgery. When teaching anatomy at Montpellier, Mondeville used fourteen illustrations to help his students visualize the hidden components of the body. These illustrations, while not accurate, were still an important step in standardizing the depiction of human anatomy; they were so influential that they were ultimately collected in a work entitled the Anathomia. From 1306 Mondeville taught and practiced anatomy and surgery at Paris, where he used full-sized versions of his previous anatomical illustrations to demonstrate human anatomy.

In addition to his illustrated guide to the human body, the Anathomia, Mondeville wrote a manual on the practice, craft, and art of surgery. This work, the Chirurgia, which appeared in both Latin and French, remained unfinished at his death. It was divided into five parts: anatomy, treatment of wounds, surgical pathology, treatment of fractures and dislocations, and pharmacology. Henri took as his sources *Galen, many of whose works were translated at Montpellier in the thirteenth century, and *Ibn Sina (Avicenna). Henri further incorporated the works of two of his near contemporaries, *Teodorico Borgognoni and Lanfranc, both of Lucca, and by both documenting and utilizing their surgical techniques contributed to the dissemination of Italian surgical practices in France. While Henri utilized the works of these authors as a foundation for his Chirurgia, he used them selectively in order to suit the needs of practical surgery. He did not use the works of these authors systematically, and since he was less concerned with theory than with practice, he was able to move beyond them to create his own ideas.

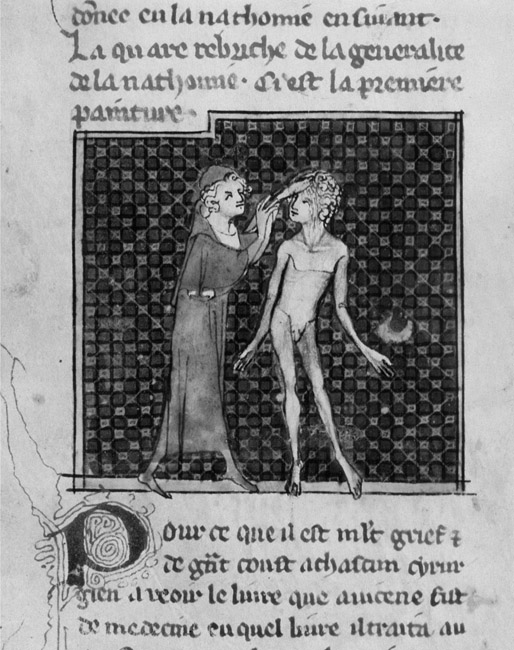

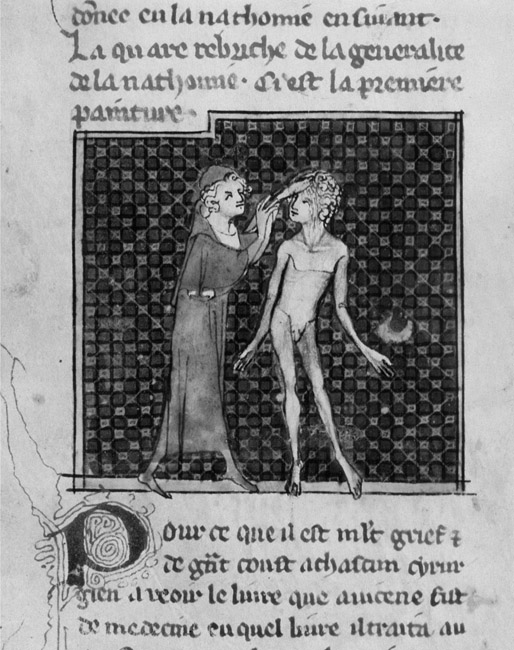

This illumination from a French fourteenth-century manuscript of Henri de Mondeville’s Chirurgia depicts a dissection. (AKG Images/Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris)

In his Chirurgia, Henri outlined not only the particulars of practice but also the place of surgery in relation to the art of medicine. Traditionally surgery was considered

a manual craft, and as such was viewed with disapprobation by learned physicians who had been trained in the theory of medicine at university. Mondeville argued that surgery was both art and craft, and therefore had a legitimate role in the medical curriculum of the university. As Simone C. Macdougall has shown, Mondeville sought not only to legitimate the practice of surgery but also to elevate it to a divine art. His Chirurgia illuminated the theoretical and practical elements of surgery as well as the financial and logistical aspects of practice necessary if one was to be successful in the field.

See also Medicine, practical; Medicine, theoretical

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Henri de Mondeville. La chirurgie de maître Henri de Mondeville. Edited by A. Bos. Paris: Firmin Didot, 1897.

———.Chirurgie. Translated [into French from Latin recension] by E. Nicaise. Paris: Alcan, 1893.

Secondary Sources

Bullough, Vern L. The Development of Medicine as a Profession. New York: Hafner Publishing, 1966.

Macdougall, Simone C. “The Surgeon and the Saints: Henri de Mondeville on Divine Healing.” In Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2000, pp. 253–267.

McVaugh, Michael. “The Nature and Limits of Medical Certitude at Early Fourteenth-Century Montpellier.” In Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 6, Renaissance Medical Learning: Evolution of a Tradition, 1990, pp. 62–84.

Pouchelle, Marie-Christine. The Body and Surgery in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990.

BRENDA GARDENOUR

Herbals

The term “herbal” (herbarium) usually refers to early printed books of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries on the therapeutic properties of plants used in medicine. However, it can be applied to earlier works dealing with the same topic, from their prototype, De materia medica (MM) by the Greek *Dioscorides (first century C.E.), to late-medieval compilations such as the early fourteenth-century Liber de herbis.

In their medieval canonical form, herbals usually consisted of a list of plants whose parts (roots, twigs, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds) were used as primary ingredients (that is, drugs) for the preparation of medicines, be they simple or composed. A chapter was devoted to each plant and all such chapters were ordered alphabetically by plant name. Each chapter normally contained the following: (a) The most commonly used Latin name of the plant and its synonyms; (b) A description of the plant; (c) The part or parts of the plant or plants to be used for therapeutic purposes (i.e., the drug or drugs), and their state (fresh or dry); (d) The preparation of the drug and, when appropriate, the proper ways to store it, that is, the type of container necessary for good conservation, without interaction between the drug and the substance of the container itself, and the maximum possible length of conservation without alteration of the drug and its properties; (e) The properties of the drug, usually expressed according to *Galen’s system, that is, according to the four primary qualities (hot and cold; dry and humid) and their grade (on a scale of four degrees); (f) The disease or diseases for the treatment of which the drug was used; and (g) A drawing of the plant, more or less developed or schematic.

After the translation period and the assimilation of Arabic texts into Western medical sciences, the schema above was modified to include a list of synonyms that included the Greek and Arabic names of plants transliterated into the Latin alphabet and often adapted to Latin phonetics but which was deformed by mistakes of all kinds. The list of diseases was very often preceded by long quotations from previous authors’ works. Such citations were attributed and ordered according to the probable chronological sequence of the authors, be they Greek (known through their Arabic versions themselves translated into Latin) or Arabic (in Latin translation). A further innovation was the inclusion of medieval commentaries on these authors; these might contain the text of the primary author, divided into thematic sections. Such commentaries tended to accumulate with the passage of time.

Byzantine and Arabic Precursors

In Byzantium, Dioscorides’ MM rapidly became the standard work for the knowledge of herbal substances used for therapeutic purposes; it seems to have been preferred to Galen’s works on the topic because of the Christianization of medicine. MM was widely spread from Egypt to Constantinople and from Rome to Syria. Its original text was rearranged several times, including the production of a herbal stricto sensu, first attested by the manuscript now in Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, medicus graecus 1, c. 513 C.E. This herbal contained about three hundred plants and their representation in color illustrations, and was abundantly reproduced until 1453 and even later in the West. Eastern plants from the original version of MM were eliminated in this herbal, and not reintroduced until the eleventh century in the manuscript now Athos (Greece), Megistis Lavras, S 75.

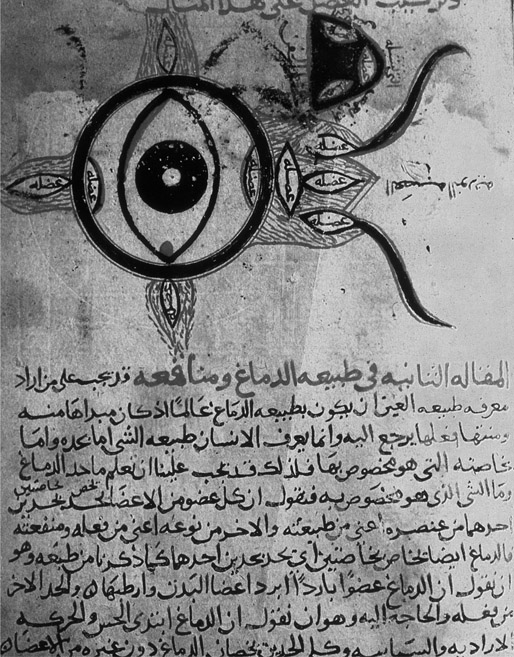

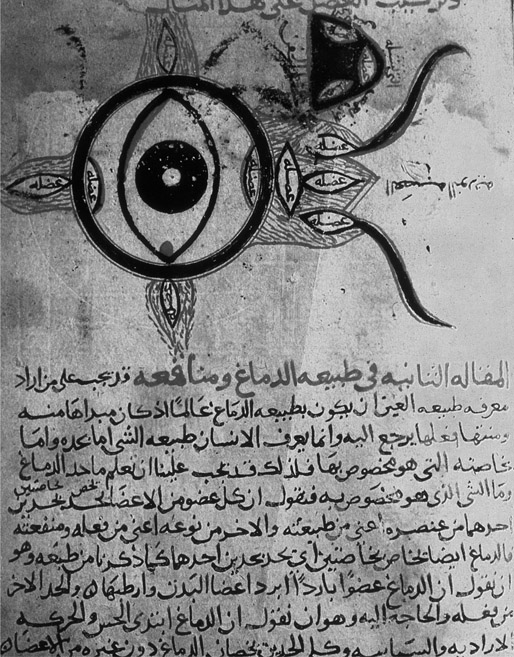

The works of both Dioscorides and Galen were translated into Syriac during the sixth century. MM was translated into Arabic twice during the ninth century by *Hunayn ibn Ishaq working in Baghdad in collaboration with Istifan ibn Basil, and several other times later on. Plant representations in early Arabic copies of MM strongly recall their Greek models, and include other decorative elements suggesting natural habitats (with animals and environmental elements such as rivers and rocks, for instance) and human uses (with representations of physicians, for example). Their works contributed to the production of original Arabic herbals (or sections on herbal drugs in larger medical encyclopedias) such as the Book on Medicinal Plants of *al-Biruni and the Canon of *Ibn Sina (Avicenna). The discursive genre of the herbal, such as represented by MM and reproduced among others by the above authors, was transformed by ibn Butlan (d. c. 1063) in the Tables of Health. He segmented textual information so as to present it in a tabular form where each column contains one single category of data: name, nature, degree, best variety, usefulness, toxicity, treatment of toxic action, property, usefulness according to patient’s temperament and age, and to season and place.

Arabic herbalism attained its apogee in the Cordoban school, whose origin dates back to the Umayyad ‘Abd al-Rahman I (756–788) and to his experiments of naturalization of Eastern plants. Local knowledge was enhanced during the tenth century thanks to a Greek copy of MM sent by the Byzantine emperor to the emir ‘Abd al-Rahman III (929–961). During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, al-Ghafiqi (first half of the twelfth century?), from Córdoba, and ibn al-Baytar (before 1204–1248), who was born in Málaga and traveled to the East, wrote the most comprehensive Arabic herbals, mainly following the MM model.

The West

Western herbals can be divided into three major chronological groups: (a) Late antiquity; (b) The translation period; and (c) The post-translation period.

(a) Late antiquity. Herbals of this period were mainly translations, adaptations, and compilations of previous or contemporary Greek and Latin works. They can be divided into two main sub-groups:

(a1) Translations and adaptations of Dioscorides’ MM, and of books 20–27 of Pliny’s Natural History, which are devoted to medicinal plants. These include (in probable chronological order): Gargilius Martialis (third century), Pseudo-Apuleius (fourth century?), Medicina and Physica Plinii (early fourth, and fifth/sixth century respectively), Theodorus Priscianus (fourth/fifth century), Vindicianus (fourth/fifth century) (now lost), Pseudo-Dioscorides, De herbis feminis (fifth century), Marcellus of Bordeaux (early fifth century), Serenus Sammonicus (of uncertain period, between second and fourth century), and *Isidore of Seville (bishop of Seville 600/601–636). Such works amalgamated local material, sometimes characterized by superstition and magic.

(a2) First medieval original syntheses, from the recipe book of Lorsch Abbey (Germany) (790 C.E.) to Hraban Maur (c. 780–856), Walahfrid Strabo (c. 808–849), and *Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179). These works reflect the development of gardens of simples in the context of Western monastic institutions, and include the newly developed Christian approach to the medicinal powers of plants, characterized by prayers to the saints Cosmas and Damian which concentrate on God’s creative power, and thus restrict speculation on the natural origin of the plant’s therapeutic power, as well as materialist theories such as those of Galen.

(b) Translation period. Translation activity started in southern Italy, be it from Arabic into Greek or Latin (for the latter, *Salerno and *Monte Cassino, with *Constantine the African [d. after 1085]), and later pursued in Spain (*Toledo, among others with *Gerard of Cremona [c. 1114–187]), southern France (Montpellier), *Arnau de Vilanova, and Sicily under Manfred, King of Naples and Sicily (1258–1266). Translations included a wide range of works, from the classical Canon of Avicenna translated by Gerard of Cremona to the Travelers’ Medical Manual of ibn al-Jazzar (d. 1004–1005) translated by Constantine as the Viaticum, and the Tables of Health of ibn Butlan translated in Sicily as the *Tacuinum sanitatis, maybe by Faraj ibn Salim (thirteenth century). All such translations were widely spread in the West. Illustrations of Tacuinum sanitatis were particularly developed in northern Italy, with the creation of a new iconic genre: plants were inserted into scenes borrowing their elements from other scientific and non-scientific fields such as agriculture and the calendar.

(c) Post-translation period. The injection of Arabic texts into Western medicine fostered the writing of new herbals such as the Regime of Health (tenth/eleventh century), the Dynamidios perhaps of Gariopontus (late eleventh century), the herbal of Platearius commonly identified by its first words as Circa instans (twelfth century), the Salernitan secrets, and the early-fourteenth century Book of Herbs, with its French translation, the Livre des simples médecines. As the latter suggests, versions in the vernacular proliferated from then onward (even though they were not a novelty of that time), in Romance, Anglo-Saxon, and German languages. The illustrations of a copy of the Liber de herbis, the early fourteenth-century manuscript Egerton 747 now conserved at the British Library (London), have a realistic character that induced historians of art to think that they were made from nature directly, rather than reproducing previous models.

During the post-translation period, new translations of Greek works were made by such scholars as *Burgundio of Pisa, *Pietro d’Abano, and *Niccolò da Reggio. Characteristically, they included Galen’s treatise On the Mixtures and Properties of simple medicines and tried to reintroduce Galen’s herbalism, which was abandoned during the early Byzantine period. In Pietro d’Abano’s pharmacological work, both Dioscorides’ and Galen’s texts are associated.

Into Print

The first printed herbal was the Herbarius Maguntie impressus (Mainz, 1484), followed by the Herbarius Patavie impressus (Passau, 1485), and the herbal attributed to Arnau de Vilanova and Avicenna (Vicenza, 1491). In the same year came the Ortus sanitatis (Mains, 1491), immediately followed by the De Plinii aliorumque in medicina erroribus by Nicolao Leoniceno (1428–1524) published in 1492 (Ferrara), which put an end to the era of medieval herbals. The work suggested a return to Greek science (that is, to Dioscorides’ MM) rather than using Pliny’s Natural History or the Latin translations of Arabic medical treatises. No new herbal appeared before the Herbarum vivae eicones by Otto Brunfels (c. 1488–1534) in 1530 to be followed shortly by the De historia stirpium commentarii by Leonhart Fuchs (1501–1566).

See also Botany; Magic and the occult; Pharmacology; Translation movements; Translation norms and practice

Bibliography

Arber, Agnes. Herbals. Their origin and evolution. A chapter in the history of botany, 1470–1670. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1912.

Collins, Minta. Medieval herbals. The Illustrative Traditions. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Daems, Willem F. Nomina simplicium medicinarum ex synonymariis Medii Aevi collecta. Semantische Untersuchungen zum Fachwortschatz hoch- und spätmittelalterlicher Drogenkunde. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1993.

Müller, Annette. Krankheitsbilder im Liber de Plantis der Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) und im Speyerer Kräuterbuch (1456). Ein Beitrag zur medizinischpharmazeutischen Terminologie im Mittelalter. 2 vols. Hürtgenwald: Guido Pressler Verlag, 1997.

Opsomer, Carmelia. Index de la pharmacopée antique du Ier au Xe siècle. 2 vols. Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann, 1989.

Riddle, John M. Dioscorides on pharmacy and medicine. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

Sadek, Mahmoud M. The Arabic materia medica of Dioscorides. St-Jean-Chrysostome: Les Editions du Sphinx, 1983.

Stannard, Jerry. Herbs and herbalism in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999.

———. Pristina medicamenta. Ancient and medieval botany. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999.

Stirling, Iohannes. Lexicon nominum herbarum, arborum fruticumque linguae latinae ex fontibus Latinitatis ante saeculum XXII scriptis. Budapest: Encyclopaedia, 1995–1997.

ALAIN TOUWAIDE

Hermann of Carinthia

Hermann of Carinthia (fl. 1138–1143) was a translator from Arabic into Latin of texts on mathematics (including *astrology) and Islam, and the author of original works on astrology and *cosmology. The various epithets attached to his name—de Carinthia, Dalmata, Sclavus—indicate that he was a Slav from the northern Balkan region; and he himself refers to “Central Istria” as his homeland in his translation of *Abu Ma‘shar’s Great Introduction. He referred to himself as “Hermannus Secundus,” perhaps in recognition that his scientific work was a continuation of that of Hermannus Contractus of Reichenau. Inspired by the example of *Thierry of Chartres, chancellor of Chartres cathedral, to whom he refers as “his most loving teacher” (diligentissime preceptor), he embarked on a program of translating mathematical works from Arabic, together with his colleague, Robert of Ketton, to improve the quality of the textbooks available for teaching the secular sciences (the seven liberal arts) in the Western schools. Many of the texts that they prepared have not survived, including their translation of *Ptolemy’s Almagest from the Arabic, which was their ultimate aim and may never have been completed. But versions of astronomical tables, of *Euclid’s Elements and Theodosius’s Spherics have been attributed to them, and evidently formed part of their enterprise. In 1143 Hermann dedicated Ptolemy’s Planisphere (on the mathematics of stereographic projection, on which the operation of the astrolabe is based) to Thierry. Robert and Hermann’s project was interrupted in 1141 by a commission from Peter the Venerable of Cluny to translate the Qu’ran and a representative collection of texts on Islam, of which Hermann was responsible for On the Generation of Muhammad (on the transmission of a divine spirit from Adam to Muhammad), and The Doctrine of Muhammad (a simple exposition of Muslim belief). Hermann was particularly interested in establishing the scientific bases of astrology in Latin, by translating works (e.g., a work on general astrology by Sahl ibn Bishr, translated in León in 1138) and compiling manuals on specific topics (e.g., texts on weather forecasting and finding treasure and lost objects). He may have worked closely with *Hugh of Santalla in putting together summae of astrological judgments based on several Arabic authorities.

Principal Achievement

Hermann’s most important contribution to astrology, however, was his translation of Abu Ma‘shar’s Great Introduction to Astrology (1140), which underpinned the whole field of astrological doctrine with rational arguments, several taken from Aristotle. Hermann used these doctrines and arguments in his original work On the Essences (1143), which was devoted to physics “whose first part” (in his own words) “considered the nature of the upper world, and second part, the nature of the lower world, these being respectively the formal causes and the material causes of all things” (from his preface to the Planisphere). The “essences” of the title are cause, movement, place, time, and “condition” (habitudo), and Hermann expertly weaves together doctrine from the Arabic and the Latin traditions to form a well-constructed synthesis on the constitution and operation of the cosmos, the formation of minerals, plants and animals, and finally the composition of man. Hermann was writing at a time when the subject matter of mathematics, physics, and metaphysics was still being established in the West. The section on “cause” in On the Essences is virtually an essay on metaphysics, while “movement” (the effect of the cause) involves discussion of physical principles, to which the astronomy of the Almagest is accommodated. The analogy of musical harmony is often invoked (e.g., in the comparison of the planets’ diversification of the movement of the first cause to the production of different pitches issuing from a single breath being blown into pipes of different lengths), and the biological language of the mating of masculine and feminine elements, characteristic of alchemy, is used. Hermes and Plato are Hermann’s most venerable authorities: the “Emerald Tablet” of Hermes—the alchemists’ credo—is quoted (perhaps for the first time in Latin) and *Plato’s Timaeus provides the model for the structure of the work, as well as for the principles of the Same and the Different which are the prerequisite for change. On the Essences was completed in Béziers, which is where we find Hermann’s one known pupil, Rudolph of Bruges, composing a work on the use of the astrolabe in 1144. It is less likely that Hermann subsequently moved to Sicily and was responsible for a translation from Greek into Latin of the Almagest, which is attributed to him in one manuscript. Throughout his works Hermann is concerned with literary quality, and On the Essences is suffused with echoes of Latin poets and Classical mythology. The combination of myth and science, which was favored by the French Schools in the early twelfth century, was soon to be displaced by a drier scientific discourse, in which Aristotle’s works were central. But Hermann’s ideas lived on in extensive quotations of On the Essences in the work of the *Domingo Gundisalvo, while his translation of the Great Introduction to Astrology was printed three times in the Renaissance.

See also Aristotelianism; Astrolabes and quadrants; Quadrivium

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Abu Ma‘shar. Great Introduction, translated by Hermann of Carinthia. In Liber introductorii maioris ad scientiam judiciorum astrorum. Edited by Richard Lemay, 9 vols. Naples: Istituto Universtario Orientale, 1995–1996, vol. VIII.

Hermann of Carinthia. De essentiis. Edited and translated by Charles Burnett. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1982; Edited by Antun S. Kalenic. Pula: JAZU, 1990.

———. “The Liber imbrium, the Fatidica, and the De indagatione cordis.” Edited by Shiela Low-Beer. Unpub. Doctoral Diss., City University of New York, 1979.

Euclid. Elements, translated by Hermann of Carinthia. Edited by H.L.L. Busard, Books I–VI. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1968. Books VII–XII. Amsterdam: Mathematisch Centrum, 1977.

Ptolemy. Planisphere, translated by Hermann of Carinthia. Edited by Johan L. Heiberg. In Ptolemaei opera astronomica minora. Leipzig: Teubner, 1907, pp. 225–259.

Secondary Sources

Burnett, Charles. “Hermann of Carinthia.” In A History of Twelfth-Century Western Philosophy. Peter Dronke, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988: 386–406.

———. Arabic into Latin in Twelfth-Century Spain: the Works of Hermann of Carinthia. Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch (1978) 13: 100–134.

———. “The Blend of Latin and Arabic Sources in the Metaphysics of Adelard of Bath, Hermann of Carinthia and Gundisalvus.” In Metaphysics in the Twelfth Century: On the Relationship among Philosophy, Science and Theology. Matthias Lutz-Bachmann, Alexander Fidora and Andreas Niederberger, eds. Turnhout: Brepols, 2004: 41–65.

Dadic, Zarko. Herman Dalmatin: Hermann of Dalmatia (Croatian and English). Zagreb: Skolska Knjiga, 1996.

Haskins, Charles Homer. Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927: 67–81.

CHARLES BURNETT

Heytesbury, William of

William of Heytesbury (before 1313–1372/3) was a fellow of Merton College, Oxford, from 1330. With *Richard Swineshead, he belonged to the second generation of Mertonian “Calculators,” building, in particular, on Richard Kilvington’s Sophismata (1325) and *Thomas Bradwardine’s Insolubilia and Tractatus de Proportionibus (1328). He develops his thought through logical puzzles, applying supposition theory, a form of semantic-logical analysis, to the explication of sophismata (problematic statements whose truth is at issue given certain assumptions). He is particularly noted, as was Kilvington, for his work on motion and the continuum. His work, though not itself empirical, helped to lay the conceptual groundwork for early modern science.

Heytesbury’s most influential work was the Rules for Solving Sophismata (1335). It consists of six chapters. “On insoluble sentences” (insolubilia) concerns self-referential paradoxes. “On knowing and doubting” deals with reference in intensional contexts. “On relative terms” considers the reference of relative pronouns. “On beginning and ceasing” and “On maxima and minima” deal with continuum. “On the three categories” examines problems in velocity and acceleration in the three categories of place, quantity, and quality.

In “On beginning and ceasing,” Heytesbury considers sophismata such as “some part of an object ceases to be seen by Socrates,” given that the object is not now, but will be immediately after now, partly occluded by an object passing in front of it. He notes that this sophisma can be given two readings. It may be asserted that there is some one given part of the object that will, in every instant after this one, be entirely occluded. Given that reading, the sentence is false. Alternatively, it may be asserted that, at every moment after this present moment, there will be some part of the object entirely occluded at that moment (a different part for each moment). On that reading the sentence is true.

“On maxima and minima” concerns the limits of capacities, as measured on the range of actions a capacity can perform. Thus one might ask what the limit of a given person’s capacity to run a distance in a given time is, measured on the continuous range of distances. In such a case there will be, it seems, either a greatest distance he can run, or a shortest he cannot, but not both, and one issue is to determine which of these options is correct in different cases. Heytesbury considers also the question when such a limit exists at all, and specifies that it will exist, for instance, as long as there is a distance that can be run in that time, and also a distance that cannot, and as long as any shorter distance can be run if a longer one can, and no longer distance can be run if a shorter cannot. In fact, this is true as long as distances form a compact continuum, but is not true if they are associated only with rational numbers, and not with irrational numbers such as the square root of two. Heytesbury’s work here, although intended for an entirely different purpose, is conceptually related to the construction of Real Numbers from Rationals by Richard Dedekind in 1872.

The “Rules” was Heytesbury’s most popular work, and remained important in Italy even after the Mertonians began to be ignored in Britain. It was made part of the curriculum at Padua in 1487, influencing the Paduan School and fifteenth-century Italian logicians such as Paul of Venice (d. 1429), and was used in Paris by the school of John Major in the early sixteenth century. With the rest of medieval logic, Heytesbury’s work sank into obscurity after that. In addition to the “Rules” Heytesbury wrote two collections of sophismata, in one of which it was repeatedly argued that the respondent was a donkey, as well as some shorter works, for instance, “On the Compounded and Divided Senses,” which dealt with scope ambiguities similar to that concerning the occluded object laid out above.

In the sixth chapter of the “Rules,” Heytesbury states the mean-speed theorem for uniformly accelerated motion: a uniformly accelerated body will, over a given time, traverse a distance equal to the distance it would traverse if it moved continuously in the same period at its mean velocity (one half the sum of the initial and final velocities). Elsewhere, he points out, in a particular case, that a uniformly accelerated body will, in the second equal time interval, traverse three times the distance it does in the first. Domingo de Soto observed the applicability of the mean-speed theorem to free fall in 1555.

See also Latitude of forms; Swineshead, Richard

Bibliography

Heytesbury, William. On Maxima and Minima: Chapter 5 of Rules for Solving Sophismata, with an anonymous fourteenth-century discussion, translated with introduction and study by John Longeway. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1984.

———. William of Heytesbury on “Insoluble” Sentences, translated with notes by Paul Spade. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1979.

———. “The Compounded and Divided Senses,” and “The Verbs ‘Know’ and ‘Doubt’,” translated by Norman Kretzmann and Eleonore Stump. In The Cambridge Translations of Medieval Philosophical Texts, Vol. 1: Logic and Philosophy of Language. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

———. “On the three categories.” Selections translated by E.A. Moody in Marshall Claggett, The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959. Reprinted in Edward Grant, A Source Book in Medieval Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974.

Wilson, Curtis. William Heytesbury: Medieval Logic and the Rise of Modern Physics. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1960.

JOHN LONGEWAY

Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) led both a very conventional and a very unconventional life. Born into a well-connected family in the German Rhineland, at twelve she entered a Benedictine monastery. Seventy years later she died in a second Benedictine monastery no more than twenty miles from her birthplace. She took few trips, the longest only a few hundred miles from her monastery; her main supporters and friends were almost all relatives.

And yet Hildegard’s life was remarkable. In her early forties she began to experience complex spiritual visions; by fifty she had completed her first book, Scivias, a grandiose illuminated text on the theological and sometimes the political implications of these visions. Two years later, despite her monastic vows, she left her first monastery and, taking most of its nuns with her, founded a new monastery at Bingen on the Rhine. Over the next thirty years she wrote many works, among them two other illuminated texts of theology, a musical drama (possibly the first in Europe), more than seventy liturgical pieces, a commentary on the Benedictine Rule, two saints’ lives, and a glossary of a private language. By the end of her life she was well known, and her surviving letters include correspondence with most of the crowned heads of Europe, as well as numerous popes, archbishops, bishops, abbots, and abbesses.

Of greatest interest to historians of science, technology, and medicine are Hildegard’s two medico-botanical works, Physica and Causae et curae. Her sources are still unknown. The texts imply that she was familiar with Galenism, folk practice, and the new Arabic medicine, and that she had gained practical knowledge of medicine as the infirmarian at her first monastery.

Physica is essentially a nine-book natural science encyclopedia (on plants, elements, trees, stones, fish, birds, animals, reptiles, and metals) in the tradition of Pliny the Elder (23–79) and *Isidore of Seville, as well as of *lapidaries, *bestiaries, and *herbals. The work consists of short passages on the medicinal properties of thousands of substances. Many of its observations are original, and even when presenting traditional information Hildegard is always idiosyncratic.

By contrast, the five-book Causae et curae is more of a manual of practical medicine, probably composed for the nun-infirmarian of Hildegard’s new monastery at Bingen. Its first book summarizes natural science and cosmology; its second book presents an abbreviated human physiology; its third and fourth books provide medicinal recipes, and the fifth book has passages on prognostic techniques. Although sometimes confusing and still controversial, the text allows an unparalleled look at how one particular medieval practitioner assimilated the varied strands of medicine available—the Greco-Roman, the Christian, and the folk-oral.

For instance, Hildegard conflates three humoral ideas, while adding a few of her own. She takes a mainly Hippocratic view of the humors as bile, blood, melancholy, and phlegm, but sometimes assumes a rather more Galenic view, treating the humors as if they were identical with the qualities of hot and cold, wet and dry. At other times she treats “humor” as if it were the unique medicinal property of a plant—its sap—linguistically the original meaning of the Greek chymos (humor). None of this prevents her from also seeing humors idiosyncratically, as higher or lower, good or bad, in parallel with her concern with hierarchy and order. But it is Hildegard’s concept of viriditas (greenness) that has provided scholars with their most important insights into the medieval body. Viriditas was originally a botanical concept signifying green sap, often used as a metaphor for the fertility of spiritual qualities. Although Hildegard does use viriditas in both these ways, she uniquely finds it also inside the body, and with hormone-like qualities. Thus her viriditas is a substance that circulates in the blood, is modified by food, and affects secondary sexual characteristics. This unique usage suggests that for her there was an implicit overlap between medieval doctor and gardener—just as the job of the gardener was to cultivate the viriditas of the plant, so the job of the physician was to nurture the viriditas of the patient.

Taken together, Physica and Causae et curae can provide the scholar with special insights into the medieval body. Long neglected, and then studied without reference to its context, Hildegard’s work should instead be a reference point for many studies of medieval science, technology, and medicine—not just as “the woman’s voice,” or “the mystic’s voice,” or even “the genius’s voice,” but as the voice of an observant and pragmatic practitioner.

See also Dioscorides; Encyclopedias; Galen; Gynecology and midwifery; Hippocrates; Hospitals; Illustration, medical; Medicine, practical; Medicine, theoretical; Microcosm/macrocosm; Natural history; Pharmaceutic handbooks; Pharmacology; Pharmacy; Regimen sanitatis; Salerno; Translation movements; Women in science

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Hildegard of Bingen. Holistic Healing. Translated by Manfred Pawlik, translator of Latin text, Patrick Madigan, translator of German text, John Kulas, translator of foreword. Edited by Mary Palmquist and John Kulas. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1996.

Hildegard, Saint. Hildegard’s Healing Plants: From the Medieval Classic ‘Physica.’ Translated by Bruce W. Hozeski. Boston: Beacon Press, 2001.

Kaiser, Paul, ed. Hildegardis Cause et curae. Leipzig: Teubner, 1903.

Migne, Jacques-Paul, ed. S. Hildegardis Abbatissae Opera Omnia. Vol. 197, Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Latina. Paris: Garnier, 1855.

Moulinier, Laurence, ed. Beate Hildegardis Bingensis Causae et cure. Vol. 1. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2003. Patrologia Latina Database (CD-Rom). Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Latina. Alexandria, VA: Chadwick-Healey, Inc., 1995.

Throop, Priscilla. Hildegard Von Bingen’s Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing. Rochester, VT:.Healing Arts Press, 1998.

Tombeur, Paul. “The Cetedoc Library of Christian Latin Texts: Cdrorn.” Turnhout: Brepols, 2002.

Secondary Sources

Berger, Margret. Hildegard of Bingen: On Natural Philosophy and Medicine. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1999.

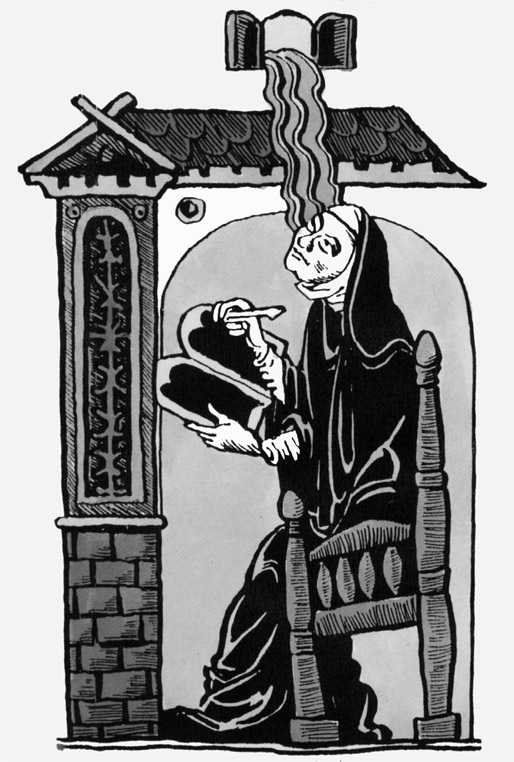

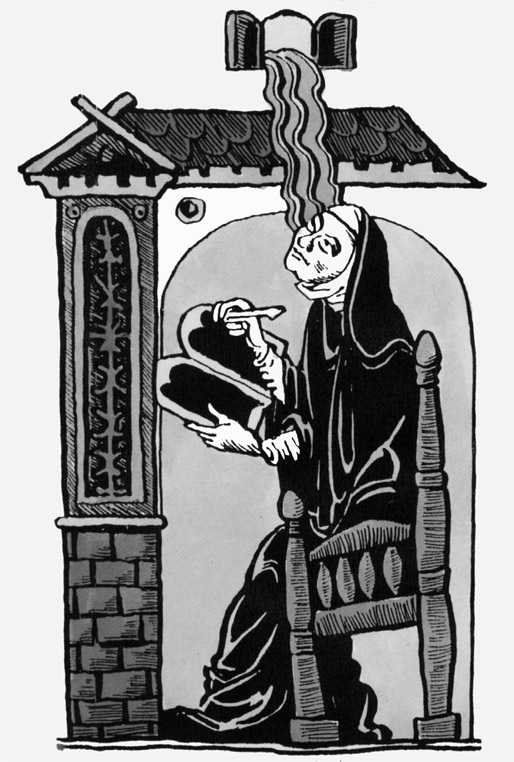

Twentieth-century rendition of a thirteenth-century Lucca manuscript illustration of Hildegard of Bingen. (Lebrecht Music and Arts Picture Library/John Minnion)

Burnett, Charles and Peter Dronke, eds. Hildegard of Bingen: The Context of Her Thought and Art. London: Warburg Institute, 1998.

Flanagan, Sabina. Hildegard of Bingen, 1098–1179: A Visionary Life. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1998.

McInerney, Maud Burnett, ed. Hildegard of Bingen: A Book of Essays. London: Garland Press, 1998.

Newman, Barbara. Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997 (1987).

——— ed. Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Singer, Charles. “The Scientific Views and Visions of Saint Hildegard (1098–1179).” In Studies in the History and Method of Science, edited by Charles Singer, 155. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955.

Sweet, Victoria. “Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine (1999) 73: 381–403.

———. “Body as Plant, Doctor as Gardener: Premodem Medicine in Hildegard of Bingen’s Causes and Cures.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California San Francisco, 2003.

VICTORIA SWEET

Hippocrates

A Greek physician, Hippocrates (460–between 375 and 351 B.C.E.) was born in the island of Kos (Aegean Sea) to a family of Asclepiads (descendants of Asclepiades, the mythological god of medicine). He practiced medicine in the north Aegean world (on the islands and the continent) in a pragmatical way (well summarized in the Aphorisms), with a special attention to the living conditions of the patients (see the treatise Airs, waters, places), physiological and pathological processes (including diagnosis and prognosis), alimentary diet and pharmacological therapy, and the interrelation between physicians and patients. On this basis, he has been traditionally credited with the development of scientific, viz., clinical medicine, free of superstition and supernatural processes (see, for instance, the treatise Sacred disease, in which the author denies that epilepsy results from supernatural causes). In the age of the Sophists, Hippocrates liked the professionalization of intellectual activities, and has been considered responsible for the transformation of the practice of medicine from a hereditary and exclusive privilege to a laicized and open profession. The Oath stipulated the conditions of the relationship of apprenticeship between a would-be physician and a practitioner-mentor. The relatives, disciples, and later followers of Hippocrates constituted the so-called School of Kos, inspired by the above principles and supposedly opposed to the School of Cnidus (on mainland Asia Minor, facing the island of Kos), characterized by a more rigid approach to medical examination and pharmacological therapy. Hippocrates’ reputation as a successful physician is attested by *Plato.

Despite having lived in a period of development of written culture, Hippocrates does not seem to have written any medical treatise. However, some works that appeared later and circulated under his name might contain material dating back to him. Some sixty treatises of different medical and philosophical origins and periods (from the fifth century B.C.E. to the second C.E.) are attributed to him in manuscripts of the Byzantine period. They deal with physiology, the etiology, semiotics, diagnosis and prognosis of diseases, dietetics, pharmaceutical therapy and surgery, and the exercise and ethics of medicine. They seem to have been circulated in thematically coherent groups that then gradually became associated so as to form the so-called Corpus Hippocraticum of modern scholarship.

As early as Herophilus (330/320–260/250 B.C.E.), existing Hippocratic treatises were studied in the medical school of Alexandria. Hippocrates’ approach to medicine, considered as of a dogmatic nature by empiricists from the Hellenistic period on, was reinvigorated and reinterpreted by *Galen. At the turn of the third century C.E., Hippocratic medicine met Christian faith, which denigrated the human body or promoted a discourse where physiological and pathological processes (of a material nature) were supplanted by a moral system of punishment and retribution (disease results from sin and healing from the grace of God). A compromise was soon reached: Hippocratic medicine was accepted provided its pagan components were eliminated. Between the fourth century and the sixth century, it was even absorbed into Christian faith, particularly with the cult of Saints Cosmas and Damianos, the so-called Anargyroi. Although these holy twins obtained their medical science directly from God (be it in pathology or therapeutics), they diagnosed and treated diseases in a typically Hippocratic way. Christianization of Hippocratic medical ethics is best represented by the layout of the Oath in Byzantine manuscripts, in the form of the Holy Cross.

In late antiquity, Hippocratic works were commented on in the Alexandria medical school by such teachers as Palladius (Fractures), Ioannes of Alexandria (Nature of Child, Epidemics 6), Stephanos of Athens (or of Alexandria) (Aphorisms, Prognostics), Asclepius (Diseases of Women) and the anonymous author of Humors. Their method followed a typical pattern: for each passage (lemma), the reading of the work was first discussed (with its possible variants); the general meaning of the lemma was then established; and the different interpretations proposed by previous authors and teachers were reviewed and discussed. Later Arabic sources have led to the postulation of the existence of a relatively rigid selection of twelve Hippocratic works studied in the Alexandrian school (the so-called Alexandrian Canon). Even though such an account should probably not be accepted too strictly, it is likely to reflect the state of affairs at the time of the takeover of Alexandria by the Arabs (642).

Translations

The Alexandrian method of teaching was reproduced in Ostrogothic Ravenna (sixth century). Some Hippocratic treatises were translated into Latin by Western teachers with a sufficient knowledge of Greek (Aphorisms; Prognostic; Diseases of Women; Airs, waters, places; Nature of man; Weeks; Regimen). These translations were made for practical rather than theoretical purposes, and seem to have also served as a basis for commentaries (instead of the Greek original text). Contrary to traditional historiography, the Lombard invasion of Italy (568) did not interrupt the tradition of the classical heritage. However, relations with the East were stronger under the Carolingians, and Hippocratic textual material arrived again from Byzantium before the eighth century as shown by the so-called Lorsch Arzneibuch (MS Bamberg, med. 1, from the abbey of Lorsch in Germany).

In the East, the twelve works of the supposedly Alexandrian Hippocratic canon were translated into Syriac by Sergius of Ra’s al-‘Ayn (d. 536). There was no Hippocratic Academy in Gundishabur, however, as claimed by a thirteenth-century historiographic tradition. Hippocratic treatises were known in the Arabic world from at least the ninth century. The Aphorisms, for example, served as a model for Masawayh’s Medical axioms. They were translated into Arabic from Greek, principally by *Hunayn ibn Ishaq and a group of collaborators. Through these translations, Hippocratic medicine made its way into original works by Arab physicians.

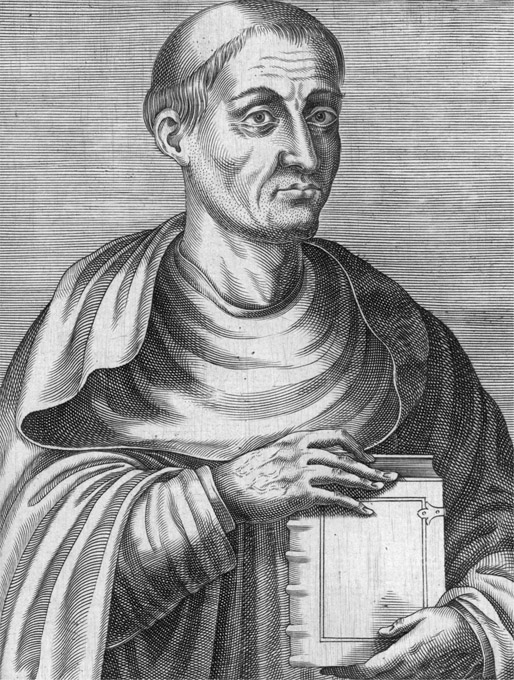

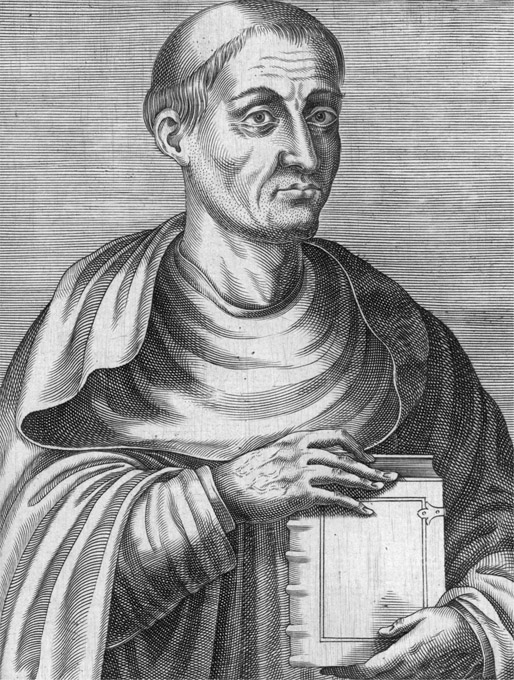

Detail of a woodcut of 1511 depicting the three great medical authorities of the Middle Ages: (left to right) Galen, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), and Hippocrates. (Corbis/Bettmann)

Greek manuscripts of Hippocratic writings (be they of the entire corpus or of single works) circulated or were produced in southern Italy. They reproduced earlier manuscripts present in Italy, or new ones coming from the East (not necessarily Constantinople). From the eleventh century on (and maybe earlier), Arabic works were translated into Latin in the West in an enterprise best represented, though probably not initiated, by *Constantine the African. This movement was aimed at recovering Greek science and reintroduced Hippocratic texts into Western medicine. Constantine translated Galen’s commentary on the Aphorisms and the Prognostica, and perhaps also the Regimen in Acute Diseases. *Gerard of Cremona (d. 1198) was responsible for the Latin version of Galen’s commentary on the Hippocratic Elements. These texts were extremely popular from the twelfth to the fifteenth century as the high number of extant manuscripts currently inventoried suggests (Aphorisms: 137; Regimen: 203; Prognostics: 246) The so-called *Articella that was thereby gradually constituted included the Aphorisms, the Prognostics, and the Regimen in Acute Diseases.

While pseudo-Hippocratic works proliferated in the West (Latin) and in the East (Greek), new Latin translations of Hippocratic or pseudo-Hippocratic works were made directly from Greek from the twelfth century on by, among others, *Burgundio of Pisa, Bartolomeo of Messina (fl. 1258–1266) (Nature of Child; Nature of Man), *Pietro d’Abano, *Arnau de Vilanova (Law), and *Niccolò da Reggio (Regimen in Acute Diseases; Aphorisms; Oath; Law; Nutriment).

At the end of the fifteenth century, Latin translations of Hippocratic treatises (be they medieval or new, viz., early humanistic ones) were printed together with the Articella or Arabic works: the Aphorisms (in the translation of Theodorus of Gaza [d. 1478]) in the 1476 edition of the Articella; Airs, Waters, Places, Nature of Man, and Remedies in the first printed edition (1481) of the Latin translation of al-Razi, Liber ad Almansorem; The Oath (Latin translation by Paolo Vergerio [1370–1444]) and Nature of Man (by Bartolomeo of Messina) in the 1483 edition of the Articella; and the Latin medieval translation of the Aphorisms in the 1489 edition of Maimonides’ Aphorisms. At the same time, new humanistic translations were published independently: the Art by Andreas Brenta (c. 1460– c. 1485) in 1481; the Oath by Niccolò Perotti (fl. 1429/1430–1480/1490) in 1483; and the Oath, Law, Nature of Man, Regimen, and the Art by Andreas Brenta, in 1489–1490. Then, a new generation of Latin translations appeared, by among others Nicolao Leoniceno (1427–1524), Wilhelm Copp (c. 1460–1532) and Lorenzo Laurenziani (d. 1515). In 1524, such single translations were first published in a collective volume. The next year, a Latin translation of Hippocrates’ Eighty Volumes was published by Marco Fabio Calvi (1440–1527), and, in 1526, the Greek text of Hippocrates’ complete works was printed in Venice by Gian Francesco d’Asola (c. 1498–1557/1558), definitively putting an end to medieval Hippocratism and transforming Hippocrates into the Father of Medicine.

See also Medicine, practical; Medicine, theoretical; Translation movements; Translation, norms and practice

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Jouanna J. 1992. Hippocrate. Paris: Fayard (English translation: Hippocrates. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

Hippocrates, Works. London: Heinemann, 8 vols., 1923–1994.

Secondary Sources

Aliotta G., D. Piomelli, A. Pollio, and A. Touwaide. Le piante medicinali del «Corpus Hippocraticum». Milan: Guerini e Associati, 2003.

Kibre P. Hippocrates latinus. Repertorium of Hippocratic writings in the Latin Middle Ages. Revised edition. New York: Fordham University Press, 1985.

King H. 2002. “The Power of Paternity: the Father of Medicine meets the Prince of Physicians.” In D. Cantor (ed.), Reinventing Hippocrates. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002, pp. 21–36.

Maloney G. and R. Savoie. Cinq cents ans de bibliographie hippocratique. 1473–1982. St-Jean-Chrysostome, Quebec: Les Editions du Sphinx, 1982.

Mazzini I., and N. Palmieri. “Les écoles médicales à Rome. Programmes et mèthodes d’enseignement, langue, hommes.” In P. Mudry, J. Piegeaud (eds.). Les écoles médicales ‡ Rome. Geneva: Droz, 1991, pp. 285–310.

Sezgin F. Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums, III. Medizin-Pharmazie-Zoologie-Tierheilkunde bis ca. 430 H. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1970, pp. 23–47.

Smith W. The Hippocratic Tradition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973.

Temkin O. Hippocrates in a World of Pagans and Christians. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

Ullmann M. Die Medizin im Islam. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1970, pp. 25–35.

ALAIN TOUWAIDE

Hospitals

The Oxford English Dictionary provides several definitions of the term hospital, including: “a house or hostel for the reception and entertainment of pilgrims, travelers, and strangers; a hospice,” “a charitable institution for the housing and maintenance of the needy,” “an asylum for the destitute, infirm, or aged,” as well as our more modern definition of “an institution or establishment for the care of the sick or wounded, or of those who require medical treatment.” An understanding of the development of the hospital as an institution, from its roots in Byzantium and the Dar al-Islam to its flowering in the medieval West, requires that we utilize these broader definitions of the structures, missions, and types of care provided by such institutions. While a majority of Byzantine and Islamic institutions provided advanced medical care administered by trained physicians, many early European medieval hostels and hospices did not. Such non-medicalized institutions are vital to the history of the hospital because they offered compassionate spiritual and physical care to the suffering, and this desire to alleviate pain is the fundamental mission behind the hospital as an institution, whether ancient, medieval, or modern.

Byzantine Hospitals

The first hospitals in Byzantium were modeled on Christian charitable institutions that had developed throughout the third and fourth centuries C.E. to house and feed the needy. Xenones, or hospices, provided food or shelter, while nosokomeion, or hospitals, provided medical care for the physically and mentally ill. St. Basil the Great founded one of the earliest hospitals at Caesarea, Cappadocia, c. 372 C.E. The nosokomeion and the surrounding complex, which became known as the Basileias, not only ministered to needy wayfarers as they passed through the province and provided spiritual care to those in crisis, but also offered therapeutic medical treatment delivered by trained physicians for those suffering in body and mind. The complex further contained areas dedicated to the care of the chronically ill, including the aged and the leprous.

St. Basil’s was only one of the earliest in a long tradition of Byzantine hospitals. Healing institutions similar to those in Alexandria, Thessalonica, Ephesus, and Constantinople were opened throughout the empire, and continued to develop well into the Middle Ages. While both the Byzantine Church, through its network of metropolitans and bishops, and wealthy individuals founded hospitals, many more were established and funded by the imperial government. In 1136, Empress Irene Komnenos founded the hospital complex of the Pantocrator of Constantinople, the typikon, or charter, of which has survived. The Pantocrator contained specialized areas for surgery, a central hearth-altar, separate chambers for men and women, areas for the chronically ill, the mentally deranged, the aged, a leprosarium, a dormitory for hospital staff, a medical school, an out-patient area, and several chapels with elaborate mosaics. Staffing at the Pantocrator was hierarchical, with the archiatros, or head physician, acting as director of thirty-five physicians, several midwives, surgeons, and pharmacists, together with a sizeable nursing staff composed of men and women. The archiatros was also responsible for managing the non-medical staff of the hospital, including cooks, launderers, groundskeepers, and provisioners. The architecture of this hospital was based on that of the monastery at Meteora, and served to reinforce the theological assertion that every illness, whether physical or mental, was spiritual in origin; the healing process, therefore, began with a cleansing of the soul, administered primarily through contact with Christ and His Saints in the sacred space of the hospital.

Hospitals in the Dar al-Islam

The development of the hospital in Islam can be attributed to contact with Greek medical texts and institutions, the growing need for medical care in the rapidly developing cities of the Islamic empire, and the practice of charity and hospitality inherent in Islamic culture. The rise of Islam in the seventh century and its phenomenal expansion brought intellectuals into contact with the textual traditions of the West. By the sixth century, medical treatises had already been disseminated to the edges of the eastern Byzantine empire. Nestorian Christians, fleeing persecution by the Byzantine Church, brought libraries of medical texts eastward into Syria, and established centers of learning, such as the famed medical school at Gondeshapur. Muslim physicians not only made use of the Greek-to-Syriac translations produced at these centers, but also gathered Greek medical treatises from Byzantine cities, such as Alexandria, which had been absorbed into the Islamic Empire. Contact with Byzantine medical culture provided Islam with the institutional foundations for the development of the bimaristan, the Islamic hospital.

Islamic culture has at its core the fundamental belief that charity and hospitality are vital practices for both the individual and the community as a whole. Muhammad called on his people to care for widows, orphans, and the destitute. Since those suffering from illness were often incapacitated to the point where they could not support themselves, they were also to be provided for by the Muslim community. Individuals, through tithing and bequests (zaqat and waqf), contributed to the support of hospitals. Ultimately, the caliphs would found hospitals and their functioning would be supported and managed by the state. Islamic hospitals were predominantly secular in orientation, in contrast to those of Byzantium. Some of the most prominent bimaristans in the Islamic empire included the leprosarium at Damascus founded by the Umayyad caliph Ibn Walid, the hospital at Rayy at which *al-Razi practiced his art, the al-Baghdadi hospital founded by Harun al-Rashid and managed by the Bakhtishu family of Gundishapur, the Mansuria Hospital in Egypt, and the Egyptian Hospital of Ibn Tulun, the functioning of which is described in detail in the memoirs of Ibn Jubayr.

Islamic hospitals, although based on the institutions of Byzantium, were not mere reproductions of a received tradition; instead, Muslim physicians used Byzantine models to create distinctly Islamic institutions. Islamic hospitals were staffed by trained physicians and nurses under the guidance of a head physician; an individual appointed by the caliph oversaw the funding and management of non-medical aspects of the institution. Within the differentiated space of the Islamic hospital were areas for internal medicine, osteopathy, ophthalmology, and surgery, as well as separate wards for men, women, and the chronically ill. The hospital also contained a medical school, with a library and classrooms, a pharmacy, baths, an outpatient area, and a mosque. One significant contribution of Muslim physicians to the design of the hospital was a ward designated solely for the treatment of the mentally ill. These wards were open to the public, and allowed patients to continue to participate in the daily life of the community.

Hospitals in the Medieval Christian West

Roman hospitals of the third and fourth centuries were Christian charitable foundations established, primarily by bishops, to provide food, shelter, and basic care to the destitute. These foundations functioned as hospices, and while providing spiritual care and the alleviation of suffering, did not offer medical treatment. Unlike Byzantine institutions of the same period, which contained specialized rooms for different types of treatment, Roman hospices generally consisted of one room, an undifferentiated space within which the sick, the poor, and the transient co-existed. This sacred space might be imagined as a small chapel in which beds and pallets of straw were arranged. Throughout the sixth century, the pope exhorted bishops to continue to found hospices; Caesarius of Arles erected such a structure for the benefit of his flock. Many of these early foundations did not survive the urban decline of the seventh century and were left to decay. Charlemagne, in the ninth century, advocated the founding of hospices for the care of pilgrims and the infirm; however, many of these institutions were destroyed by subsequent barbarian invasions and political dissolution.

In addition to the Roman type of hospice was the monastic infirmary. The Rule of Saint Benedict called for the charitable care of the destitute and infirm. In response to this demand, Benedictine monasteries housed infirmaries for the care of sick inmates, and when necessary, people in the surrounding community. Both body and soul were treated simultaneously in the monastic infirmary. The infirmarian, acting as physician, utilized medicaments, such as salves and purgatives, as well as therapeutics, such as dietary regimens and massage, to treat bodily illness. The monastic community helped to heal the souls of the suffering through prayer, liturgy, and communion; the proximity of saintly relics also provided physical and spiritual benefits. In some cases music was allowed in the infirmary to help soothe the souls of the sick, thereby facilitating the healing process. The monastic infirmary was originally an undifferentiated space; however, by the ninth and tenth centuries a level of differentiation had been achieved, with the infirmary being divided into an area for the acutely ill, a pharmacy used for the concoction of medicines and blood-letting, a bath area, and a garden for growing medicinal herbs.

The medieval hospital advanced as a medical institution due to the reception of Eastern medical traditions via the translation of medical texts, as well as through contact with eastern hospitals during the Crusades. Early translations were made at the Benedictine monastery of *Monte Cassino, where *Constantine the African (fl. 1065–1085) rendered Arabic treatises, such as the Pantegni of *‘Ali ibn al’Abbas al-Majusi, into Latin. In the twelfth century, scholars such as *Gerard of Cremona traveled to Spain in search of medical treatises, carrying them northward to monasteries, cathedral schools, and universities. The dissemination of medical texts, the development of the university, and a demand for medical care by the elite contributed to the development of the medical profession. By the thirteenth century, the physician was a recognizable member within the community. While private practice was predominant, physicians also donated their time for the sake of charity, and brought learned medical practice into the medieval hospital.

The Crusades brought Europeans into direct contact with Eastern hospitals, such as that of Saint John of Jerusalem. The structure of Saint John’s Hospital was Byzantine, with differentiated areas for specialized activities. It was staffed by trained physicians and nurses who cared for the inmates. In 1125, the Knights of Saint John’s Hospital, or the Hospitallers, were recognized as an official order, and were placed in charge of Saint John’s. As the order expanded, the Hospitallers founded and staffed hospitals throughout the Mediterranean and Europe.

The Hospitallers were only the most prominent of a myriad of orders dedicated to the care of the sick. Religious confraternities and lay brotherhoods, particularly the Augustinian Canons, offered their services both by running hospices and by nursing in hospitals. This desire to care for the destitute and the suffering came in response to the needs produced by the rapid urbanization of the twelfth century; overcrowding, poverty, and unsanitary conditions combined to create an environment rife with disease. In the twelfth century, there was not only a physical and social need for hospital care, but also a spiritual desire to offer health care as a form of charity. During this period, Christ’s humanity, and the suffering of His flesh, became powerful religious concepts. As Christians meditated on the suffering of Christ, they were called to alleviate the suffering of their fellow Christians. In response, people not only supported hospitals through almsgiving, but also by performing the arduous tasks involved in nursing. In the thirteenth century, the Beguines of the Lowland countries were vital suppliers of nurses for urban hospitals.

Late-period Problems

The fourteenth century marked a period of decline for the medieval hospital. Increased urban poverty taxed funding institutions beyond their means. And while hospitals continued to function, the quality of care offered in them was compromised not only by the high demand for trained physicians outside the hospital, especially during the Black Death, but also by the waning of pious charity among the general population. Ultimately, hospitals would fall under secular control and offer far lower amounts of compassionate care than institutions of the twelfth century. Specialized facilities, such as those for the housing of orphans, the aged, and the insane, came to dominate. In general, the inmates of these facilities were neither incorporated into the broader Christian community nor treated as objects of compassion. Instead they were categorized as “the sick,” and thus sequestered from the “healthy” for the protection of society.

See also Medicine, practical; Medicine, theoretical; Surgery

Bibliography

Brodman, James. Charity and Welfare: Hospitals and the Poor in Medieval Catalonia. Pittsburgh: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

Byrd, Jessalynn. “Medicine for Body and Soul.” In Religion and Medicine in the Middle Ages. Edited by Peter Biller and Joseph Ziegler. Leeds: Leeds University Press, 2001.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1973.

Grmek, Mirko, ed. Western Medical thought from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Translated by Antony Shugaar. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arab Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society. London: Routledge, 1998.

Horden, Peregrine. “Music in Medieval Hospitals.” In Religion and Medicine in the Middle Ages. Edited by Peter Biller and Joseph Ziegler. Leeds: Leeds University Press, 2001.

Lindberg, David. The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992.

Miller, Timothy S. The Birth of the Hospital in the Byzantine Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

Miller, Timothy S. The Knights of Saint John and the Hospitals of the Latin West. Speculum (1978) 53: 709–733.

Numbers, Ronald and Daryl Amundsen, eds. Caring and Curing. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Rawcliffe, Carole. Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death, and Resurrection of an English Medieval Hospital. Gloucester: Sutton Publishing, 1999.

Risse, Guenter. Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

BRENDA GARDENOUR

House Building, Housing

The first-century-C.E. Roman historian Tacitus described in his work Germania the living conditions and communities of a tribe of people living to the north of Rome: the Germans. Included in Germania are examples of different types of German houses. Two of these houses would become popular throughout Europe and endure throughout most of the Middle Ages. The first was the sunken hut. This consisted of a pit, approximately three feet (0.9 m) deep and covered with a roof of animal dung or a mixture of leaves, twigs, and mud. These houses were typically small, with an area of approximately thirty square feet (2.8 sq m) and were used for many purposes, including storage, living space, and as workshops.

Tacitus also described the timber-framed house. This type of dwelling was much more common than the sunken hut, and gradually replaced it. It had an important architectural feature, known as a cruck, which allowed for high ceilings. A cruck consists of a tree trunk and its lowest branch: the wood was split horizontally and the halves were placed opposite each other, forming a type of arch. The trunk served as part of the wall frame and the branch as part of the roof frame. A beam ran horizontally along the top of the cruck arch to form the peak of the roof. The vertical tree trunks were squared off and placed into post holes dug in the earth, which allowed for a snug fit between the wall and the ground and provided greater protection from the elements. In addition, the beams were portable and often were reused in the construction of new houses. Over time, stone pads were placed at the bottom of the post holes to allow the frame of the house to rest on a solid base; such stability proved very important in the rainy climate of northern Europe.

Medieval timber-framed houses ranged in size from as little as approximately two hundred square feet (18.6 sq m) to more than twelve hundred square feet (111.5 sq m). House size was often described by indicating the number of bays a house possessed; a bay is the space between the vertical beams. A small cottage would have one bay, while a larger house would have as many as three or four. Bays were laid on a single axis, producing very narrow buildings: consequently, the largest houses are often referred to as long houses (longa domus) and are perhaps the most famous type of medieval house. Long houses are also called mixed houses, as domesticated animals were often allowed to inhabit a portion of the dwelling: the animals were usually separated from the human occupants by a partition. Despite their size, the typical long house rarely contained more than one or two rooms.

The walls of timber-framed houses were made either of cob or of wattle and daub. Cob is a combination of mud, straw, and chalk that dries extremely hard. Because it is not baked, however, it is very susceptible to water, which causes it to erode. Wattle and daub is a woven mat of twigs and branches covered with mud. Neither cob nor wattle and daub are very durable, and medieval timber-framed houses were not built to last. Their building materials guaranteed their impermanence, and houses often became uninhabitable after less than twenty years. In addition, wattle and daub walls were so weak that the crime of housebreaking—entering a house through the wall itself—was not uncommon.

The roof of a timber-framed house was usually thatched with reeds, sticks, or straw. A hole was cut into the roof to provide ventilation for the stone hearth in the house; to avoid fires, the hole was often surrounded by tiles. Roof material was not only very susceptible to fire, but also rotted in the rain and provided a breeding ground for insects, birds, and rats; the latter were especially dangerous in a society where plague was common.

Regional varieties existed throughout Europe. In Italy, for example, the poor lived in similar one-room cob houses with thatched roofs. Wealthier farmers, however, used brick or stone for walls, and roofs were made with clay tiles. These houses were larger than timber-framed houses, and often were divided into several rooms. In Spain, the poorer people living in Muslim kingdoms inhabited what later Christian settlers called casas moriscas. The walls were of cob or tabby (Spanish, tapia: earth mixed either with pebbles or some other aggregate, with straw as a binding agent) packed down in a mold and built up in courses. Casas moriscas had two stories: the lower story contained a bedroom or living room along with a kitchen and a corral, and the upper story usually served as a storehouse agricultural products.

By the end of the Middle Ages better building material was increasingly available, and village houses frequently had masonry foundations, were larger, and were built on stronger frames.

Cities

The bulk of medieval urban housing was also of the timber-frame variety, although stone houses were much more common in cities than they were in the countryside. Stone and brick were usually reserved for the wealthy, however, and the houses of the poor were typically constructed from cob and had thatched roofs. Urban houses possessed multiple stories. The size of these houses often caused their frames to sag and lean as they grew older. It was not uncommon for poorer families to inhabit a single room in a house, or for a house to have several families residing in it. The wealthier were able to afford an entire house.

The first floor of a wealthy house usually served as a place of business, and a staircase in the back led up to the family domain. The second floor was dominated by the solar, a large open dining and living room. Connected to the rear of the solar was the kitchen, and the two rooms shared a large, common fireplace. The third stories and above served as bedrooms.

The windows of these houses were covered with oiled parchment, *paper, or fabric, as glass was not a readily available commodity; shutters were often an added protection from the elements. Consequently, these houses could be quite dark, and candles, lamps, and the hearth provided most of the light.

See also Stone masonry

Bibliography

Duby, Georges, ed. A History of Private Life. Vol. II: Revelations of the Medieval World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Gies, Joseph and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval City. New York: Harper Collins, 1981.

———. Life in a Medieval Village. New York: Harper and Row, 1990.

Glick, Thomas F. From Muslim Fortress to Christian Castle: Social and Cultural Change in Medieval Spain. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995.

Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Ties that Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

ANDREW DONNELLY

Hugh of Saint-Victor

Hugh of Saint-Victor (d. 1141) was born in Saxony, perhaps c. 1096, and initially educated at Hammersleben, in the diocese of Halberstadt. In 1115, Hugh traveled to France in the company of his uncle, the archdeacon of Halberstadt, ending up at the newly founded abbey of Saint-Victor in Paris. This abbey, initially established in 1108–1109 as a community of Augustinian canons by William of Champeaux (d. 1122), quickly became a major stimulus for reform of the church in France under its first abbot, Gilduin. Hugh of Saint-Victor soon emerged as the abbey’s leading teacher, making Saint-Victor famous as a center of intellectual and spiritual life, rivaling the schools of Notre-Dame and Sainte-Geneviève.

Hugh of Saint-Victor. Unattributed engraving in Vrais portraits et vies des hommes illustres (1584) by André Thevet (c. 1516–1592). (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Hugh was always fascinated by the relationship between the material world and the spiritual life. One of Hugh’s earliest major writings is De tribus diebus, a meditation on how physical creation manifests the power, wisdom, and benignity of God, thus leading humanity to reflect on the trinitarian nature of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Because *Peter Abelard argued that the three persons of the Trinity were names given to signify these three divine attributes in the Theologia ‘Summi boni’ (c. 1120), it has traditionally been assumed that Hugh must have drawn on the work in De tribus diebus. Reversing this view, Dominique Poirel has argued that Hugh may have written De tribus diebus before Abelard’s first discussion of the Trinity, perhaps c. 1118–1119. Whatever the exact relationship between these two writings, Hugh was much more interested than Abelard in the physical attributes of the sensible world, which he describes as being like a book through which God’s power, wisdom, and benignity are revealed. He was more interested in the tradition of Plato’s Timaeus than in the writings of Aristotle about language.

Probably in the early part of his teaching career, Hugh completed a series of introductions to the liberal arts. His treatise De grammatica was largely dependent on Donatus and *Isidore of Seville, and did not develop any speculative issues about the meaning of words, such as fascinated William of Champeaux and Peter Abelard. Instead, he transferred his attention to questions relating to the visible world. In his treatise on the practice of geometry (Practica Geometriae), Hugh investigates measuring height (altimetria), measuring distance (planimetria), and measuring the size of the cosmos (cosmimetria). Hugh does not claim to advance new ideas in this treatise, only to bring together scattered ideas of great thinkers of the past. He draws in particular on the Geometria attributed to *Gerbert of Aurillac, and above all on the commentary of *Macrobius on The Dream of Scipio, to reflect on a range of practical issues, above all the relationship between the diameter of the Earth and the diameter of the Sun, and the role of a curved horizon. We do not know if Hugh ever completed the treatise he promised at the end of the Practica Geometria, about the movements of the heavens, perhaps also inspired by Macrobius. Hugh did complete, however, a treatise De mappa mundi, in which he uses a physical image of the world to draw out a spiritual theme about the true Jerusalem.

Hugh was also very original in the way he integrated mechanical arts into his vision of philosophy. In his Epitome Dindimi in philosophiam, he expands the traditional three-fold division of logica, physica, and ethica (attributed to Plato by Augustine in De civitate Dei VIII.4), into a four-fold system by dividing physica into theorica and mechanica. This imitated an Aristotelian distinction between the theoretical and the practical, transmitted by *Boethius in the first version of his commentary on Porphyry. Drawing on a statement in Boethius’s De trinitate, Hugh further divides theorica into mathematica, physica, and theologia, while mechanica he defines as fabric-making, tool-making (armatura, sometimes mistranslated as “armament”), commerce, agriculture, hunting, medicine, and theatrics. While Isidore had identified mechanica as one of seven branches of physica (alongside arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy, astrology, and medicine), no previous writer had related practical skills to philosophy in such detail. Hugh argues that as human actions have a moderating wisdom, without which they cannot accept form, they should not be considered completely apart from philosophy (Epitome, ed. Baron, p. 196).

Hugh expands this system in greater detail in Didascalicon, written perhaps c. 1127 as a manual explaining how all the liberal arts relate to philosophy. Here he explains that logica was the last of the arts to be discovered, and leaves this to the end of his treatise. He gives attention first to the theoretical or speculative arts, namely theology and mathematica, dealing with abstract quantity and embracing the *quadrivium (arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy), and then to the various crafts that come under mechanica. Hugh’s account is remarkable for the absence of negative remarks about all of these practical skills, including professions such as commerce, medicine, and theater, which were elsewhere often regarded as inferior because of their worldly nature. Hugh is aware of the works of the major pagan authors on each of these skills, but does not go into detail. His larger theme is to compare their practical wisdom to the sacred wisdom of Holy Scripture, which needs to be studied both at a historical and tropological level.

After writing the Didascalicon, Hugh seems to have devoted his attention to theological issues. While he had written extensively on the meaning of the books of the Old Testament, it is only in his De sacramentis, written in the 1130s, that he developed the theological synthesis for which he became famous. Hugh’s major theme was that the history of salvation is one of creation and restoration. The process of restoration is achieved through the notion of sacrament, understood as a material symbol becoming charged with sacred significance, and thus leading humanity back to God. While there were the equivalent of sacraments before Christ, it is only with the incarnation that God has become fully accessible to humanity.

See also Scientia

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Gautier-Dalché, Patrick, ed. La ‘Descriptio mappe mundi’ de Hugues de Saint-Victor: texte inédit avec introduction et commentaire. Paris: Etudes augustiniennes, 1988.

Hugh of Saint-Victor. Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera Propaedeutica. Edited by Roger Baron. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966. [Practica geometriae, De grammatica, Epitome Dindimi in philosophiam]

Hugh of Saint-Victor. Practical geometry. Practica geometriae. Translated with notes by Frederick A. Homann. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1991.

Sicard, Patrice, ed. Hugues de Saint-Victor et son école. Turnhout: Brepols, 1991.

The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: a medieval guide to the arts. Translated with notes by Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

Secondary Sources

Allard, Guy H. “Les arts mécaniques aux yeux de l’idéologie médiévale.” In Les arts mécanique au moyen âge, ed. G. H. Allard and S. Lusignan. Montréal-Paris: Bellarmin-Vrin, 1982. pp. 13–31.

Baron, Roger. Sur l’introduction en Occident des terms geometria, theorica et practica. Revue d’histoire des sciences (1955) 8: 298–302.

Coolman, Boyd Taylor. Pulchrum Esse: The Beauty of Scripture, the Beauty of the Soul, and the Art of Exegesis in Hugh of St. Victor. Traditio (2003) 58: 175–200.

Poirel, Dominique. Hugues de Saint-Victor. Paris: Cerf, 1998.

Vallin, Pierre. ‘Mechanica’ et ‘Philosophia’ selon Hugues de Saint-Victor. Revue d’histoire de la spiritualité (1973) 49: 257–288.

Vermeirre, André. “La navigation d’après Hugues de Saint-Victor et d’après la pratique du XIe siècle.” in Les arts mécaniques au moyen âge, pp. 51–61.

Whitney, Elspeth. “The Artes Mechanicae, Craftmanship and Moral Value of Technology.” In Design and Production in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Essays in Honor of Bradford Blaine, ed. Nancy van Deusen. Ottawa: Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1998. pp. 75–87.

CONSTANT J. MEWS

Hugh of Santalla