N

Natural History

Most medieval writings on this subject are influenced by Pliny, whose encyclopedia of the first century C.E., Historia naturalis (Natural History), became the model for the genre and the principal source of similar works of late antiquity, including those of Aelian and Solinus. Pliny’s massive survey of the lands and peoples of the empire, of which around two hundred manuscripts survive, was a seemingly inexhaustible source of data about animals, plants, and minerals. The origin of properly medieval writing on nature can be traced to the “hexaemeral literature,” a group of commentaries on the biblical narrative of the six days of creation. Written by Patristic authors including Basil and Ambrose, and incorporated into the commentaries on Genesis by Augustine and *Bede, these works contain information on living creatures, plants, and animals taken from Greco-Roman sources. In his On Christian Doctrine, Augustine (d. 430) envisaged two complementary intellectual programs regarding the study of nature in the context of Biblical exegesis. On the one hand, he enjoined believers to write about animals, trees, herbs, and stones that could be of help in the interpretation of those passages in the Bible in which these things are mentioned. On the other hand, he discussed the broader question of the allegoria in factis (“allegory of things”), by which he meant that not only the words but also the natural creatures mentioned in scripture are themselves signs and as such susceptible of being interpreted. These two projects were actually fulfilled with the development of the medieval encyclopedias. A substantial part of all of them is concerned with natural history. Of the twenty books of *Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies—a vastly influential encyclopedia of the seventh century—four deal with beasts, geography, plants, and minerals.

Late twelfth- and thirteenth-century encyclopedias such as *Alexander Nequam’s On the nature of things, *Bartholomaeus Anglicus’s On the properties of things, and cognate works in the Dominican tradition such as *Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum naturale (Mirror of Nature) and *Thomas of Cantimpré’s On the Nature of Things were mainly devoted to natural knowledge. Insofar as these works drew on Pliny, Solinus, and Seneca—besides many ancient and early medieval works in Latin and Arabic—they embodied the closest approximation to what can be considered as a medieval natural history. It should, however, be borne in mind that the aims and structure of these works were very different from those of their Roman models. For one thing, these medieval treatises were conceived with an explicit religious goal in view. Nature was not the pagan deity of antiquity, nor even the hand-maiden of God in His creation (as was the case in the twelfth-century Platonic works on nature), but “the nature of a thing,” expressing that which makes a particular kind of being what it is as the result of having been created by God. The proclaimed purpose of the treatises on the nature of things was to deploy the programs formulated by Augustine. In most cases, minerals, plants, and animals were listed alphabetically within sections which mirrored the medieval taxonomy of natural creatures. For example, Thomas of Cantimpré’s On the Nature of Things has six books on animals (quadrupeds, birds, sea monsters, fish, serpents, and vermes [worms]), two books on plants (trees, aromatic trees, herbs), and two on minerals (stones and metals). Such classifications, indebted to folk taxonomy and Biblical lore on nature, are quite representative of other works of the same kind. Many of the short chapters devoted to animals end with one or more allegorical interpretations of the beast or bird; the chapters on plants are mainly concerned with their medical uses. In the late thirteenth and the fourteenth century, these works gave way to moralized encyclopedias and collections of exempla. These were explicitly conceived as tools for preaching, and purported to provide interesting stories taken from allegorized properties of animals and plants which could be used to enliven sermons and for moral edification.

Animals, Plants, and Stones

Discourse on natural history, considered as the sum of texts on animals, plants, and minerals, was fragmented in a variety of genres of writing, each of which expressed a particular attitude to knowledge. All this literature, ultimately derived from antiquity and with roots in popular lore and theological and literary traditions, constituted a complex and fluid system of textual borrowings.

In the case of animals, the most representative genre was perhaps that of the *bestiaries. An important difference between bestiaries and works on the nature of things was that in the former what is said about a given animal is in great part determined by the moral and religious teaching which is the main purpose of the work, while in the latter there is a neat distinction between the account of the animal and its interpretation. Technical works on animals comprised the books on hunting—such as The Hunting Book of Gaston Phébus (fourteenth century)—and the rich literature on hawking, with the outstanding example of *Frederick II’s On the art of falconry. There were also texts on animal medicine, either of accipiters or of horses (examples of the latter are the treatises by Jordanus Rufus, Lorenzo Rusio, and *Teodorico Borgognoni). Non-European animals were outstanding characters in the literature of travels to the Far East. Some of these works were accounts of real voyages, such as those of *Marco Polo and the Franciscans William of Rubruquis and John of Plano Carpini, while others were imaginary, like the Travels of *John Mandeville. Fantastic beasts inhabited the literature on exotic lands, including the Latin and vernacular Alexander romances and associated texts. Purely literary works, such as collections of fables and fabliaux, also contributed to medieval lore on animals.

Knowledge about the vegetable world was mainly transmitted through the *herbals, which focused on the healing virtues of a given plant and contained instructions for its collection, preparation, and dosage. Although medieval *pharmacy was for the most part herbalistic, it did not exclude animal and mineral substances. The early medieval Sixtus Placitus’s Book on quadrupeds, for instance, was a treatise on animal drugs and *Hildegard of Bingen’s Physica is a treatise that recapitulates in its nine books the healing properties of minerals, stones, trees, plants, quadrupeds, and fish. One of the first incunabula, the Hortus sanitatis (Garden of Health) (Mainz, 1491), although usually considered a herbal, amounts in fact to an illustrated natural history, with more than one thousand small woodcuts of minerals, plants and animals. As was the case with animals, there is also technical literature on plants, particularly on gardening and *agriculture, such as the treatise of Petrus Crescentius which also has books on animal husbandry, veterinary and hunting.

With respect to the mineral world, the characteristic genre was the *lapidaries, mostly dealing with precious and semi-precious stones.

The medieval menagerie, as represented in texts, pictures, and sculptures, was populated with many wondrous and some monstrous beings. For a number of reasons, animals were more the vehicle of legend and imagination than plants. This is explained by the fact that bestiaries relied on allegory, while herbals served a practical purpose (although the technical literature of hawking and hunting is quite sober in this respect). Many of the manuscripts containing texts on natural creatures were illustrated. In the thirteenth century, visual images of birds, beasts, and plants in manuscript illuminations and sculpture became more “naturalistic” through the growing development of techniques of “realistic” depiction.

Natural History and Natural Philosophy

Besides the literary genres mentioned so far, it should be noted that the Aristotelian and pseudo-Aristotelian works on animals and plants gave rise to a strong tradition of commentary. *Albertus Magnus (Albert the Great) commented on Aristotle’s books on animals and wrote original works on minerals and plants (the pseudo-Aristotelian On Plants was translated and commented on by *Alfred of Sareschel). One of the remarkable aspects of Albert’s work is that he incorporated into his Aristotelian commentaries works which pertained to other genres of writing: a lapidary, a herbal, and a dictionary of animals. Taken as a whole and with his short treatise on geography, this set of books constitutes an attempt to deal with the three kingdoms of nature from the point of view of natural philosophy. In order to include an inventory of created beings into his Aristotelian project, Albert tailored and modified his materials. While he claimed that these things were not properly philosophical, nonetheless he used them to enrich the Aristotelian commentaries with a concern for particular species. During the thirteenth century the Dominican friars became engaged in a common and energetic inquiry into nature. It has been argued that the ultimate goal of this activity was to provide stabilized meanings to the interpretation of nature attuned to the orthodox teachings of the Christian church. The resulting works cover a wide spectrum: from the encyclopedia of Thomas of Cantimpré, akin to natural history, to the natural philosophical commentaries of Albertus Magnus.

See also Agriculture; Aristotelianism; Bestiaries; Botany; Encyclopedias; Geography, chorography; Illustration, scientific; Mineralogy; Nature: the structure of the physical world; Pharmaceutic handbooks; Religion and science; Travel and exploration

Bibliography

Abeele, Badouin van den. Bestiaires encyclopédiques moralisés. Quelques succédanés de Thomas de Cantimpré et de Barthélemy l’Anglais. Reinardus (1994) 7: 209–228.

Asúa, Miguel de. El De animalibus de Alberto Magno y la organización del discurso sobre los animales en el siglo XIII. Patristica et Mediaevalia (1994) 15: 3–26.

Cummins, John. The Hound and the Hawk. The Art of Medieval Hunting. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988.

French, Roger K. Putting animals on the map: the natural history of the Hereford Mappa Mundi. Archives of Natural History (1994) 21: 289–308.

French, Roger K. and Andrew Cunningham. Before Science. The Invention of the Friar’s Natural Philosophy. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996.

Herdson, Noel, ed. An Early English Version of Hortus sanitatis. London: B. Quaritch, 1954.

Nauert, Charles G., Jr. Humanists, Scientists and Pliny: Changing Approaches to a Classical Author. American Historical Review (1979) 84: 72–85.

Stannard, Jerry. “Natural History.” In Science in the Middle Ages. Edited by David C. Lindberg. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Steel, Carlos, Guy Guldentops and Pieter Beullens. Aristotle’s Animals in the Middle Ages. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1999.

Yapp, William B. Birds in Medieval Manuscripts. London: The British Library, 1981.

MIGUEL DE ASÚA

Nature: Diverse Medieval Interpretations

The concept of Nature is Greek in origin. The word for Nature is Physis. There is considerable debate about the meaning of this word. For Aristotle, its original meaning seems to have been the coming to be of growing things. Aristotle himself provides a more detailed definition of the word in his account of the fundamental concepts of Physics. The Latin term Natura as a translation of Physis signifies “to be born,” or birth. And after about 1255 Aristotle would be institutionalized in the university learning of the day as the “authority” in philosophy: Philosophus. Earlier Neo-Platonic interpretations of Nature would be overshadowed for the academic philosophers but would persist and be revived by Marsilio Ficino in the fifteenth century. In the early fourteenth century, Petrarch in The Ascent of Mont Ventoux would present a more naturalistic and humanistic perception of nature.

To read modern philosophical commentary, however, the reader is left with the impression that the Middle Ages lacked a concept of Nature. Heidegger holds that the Latin translation of the Greek word “Physis” as “Natura” led to a loss of meaning. Pierre Hadot holds that the Middle Ages witnessed a divorce between philosophical discourse and a way of life. Thus, even Platonism and *Aristotelianism “were reduced to the status of mere conceptual material which could be used in theological controversies.” Philosophy is represented as the servant or even the slave of a superior theology or wisdom. Moreover, in Nature and Man in the Middle Ages, Alexander Murray argues that, despite the literature on this concept, there was no concept of nature in the Middle Ages.

If this is all that can or should be said about the concept of Nature in the Middle Ages, perhaps one ought to close the book on the subject. There are problems here, however. First, translation is not just the story of fundamental loss of meaning. Second, among the significant Philosophers as distinct from what *Roger Bacon calls the “common students” of philosophy, there was a keen sense for the Greek and Latin meanings of the word “Nature.”

Is there a kernel of truth in the views of Heidegger and Hadot? Yes, there is. For Augustine, who is a major source for medieval thought, and for René Descartes who is commonly seen as the “authority” or founder of modern philosophy, philosophy itself is primarily concerned with the following subject-matter: God and the Soul. In such a view of things, Nature as such, as a primary principle of change and motion, disappears out of view or at least becomes a matter of secondary consideration. God is the truly creative principle and created things are caused or produced by God.

This curtailment of the pagan Greek and Latin scope of the word “Nature” can be seen in the apologetics of Latin writers such as Prudentius, Lactantius, and Ambrose. For Prudentius, Nature is the servant of God’s handiwork. Nature is both a pro-creator and a sustainer of humanity. She assists in the creativity of God. Nature herself does not have a “moral authority”; she can only serve, not judge. In Lactantius, one notices the contrast between the art/intelligence of the divine creator and what is created, namely, Heaven and Earth. For Ambrose, nature is the work of God, is subordinate to God, but is also the pro-creator of the birth of natural things. Natural things follow a Law of Nature which has been ordained by God.

Personification

Still, the thinkers of the Middle Ages did not quite forget Nature (Natura). And rather than being the “servant” or “slave” of a superior wisdom, as Hadot implies, Nature (Natura) as the personification of that wisdom had the status of a Goddess. Hence, if Nature is a servant, she is no mere subordinate. She will have to be Pro- or Co-Creator. Nevertheless, with the institutionalization of Aristotle in the thirteenth century, this aspect of Nature as divine would gradually give way to a more “secular” and scientific understanding. And much of the later Francis Baconian masculine birth of time will be prefigured in this philosophical Aristotelian understanding of nature in Latin philosophy. In this world, nature as feminine has been abolished as an important concern to philosophy.

To understand the concept of Nature in the Middle Ages, it is important to understand the origins and uses of this concept. Four thinkers are fundamentally important for the development of the concept. They are Augustine, *Boethius, Pseudo-Dionysius, and *John Scottus Eriugena. They were supplemented by various texts having a Platonic or Stoic background.

Even Augustine did not altogether exclude Nature. In his important De doctrina christiana, he retains a strong distinction between natural and conventional meaning. Nature is something to be explored and understood by means of “number, weight, and measure.” To gain a sense of the Greek meaning of Nature as understood in the early Middle Ages, however, one needs to turn to Boethius, Pseudo-Dionysius, and Eriugena.

Boethius presents his definition of Nature in Contra Eutychen: “Nature, then, may be affirmed either of bodies alone or of substances alone, that is, of corporeals or incorporeals, or of everything that is in any way capable of affirmation.” Since, then, nature can be affirmed in three ways, it must obviously be defined in three ways. For if you choose to affirm nature of the totality of things, the definition will be of such a kind as to include all things that are. It will accordingly be something of this kind: “Nature belongs to those things which, since they exist, can in some measure be apprehended by the mind.” This definition, then, includes both accidents and substances, for they can be apprehended by the mind. The phrase “in some measure” is included because God and matter cannot be apprehended by the mind, be it so whole or perfect, but they still are apprehended in a measure through the removal of accidents. The reason for adding the words, “since they exist” is that the mere word “nothing” denotes something, although it does not denote nature. For it denotes, indeed, not anything that is, but rather non-existence, but every nature exists. And if we choose to affirm “nature” of the totality of things, the definition will be as we have given it above.

In Book Four of the Consolation of Philosophy Boethius presents his account of the place and role of Nature in the ordering of the universe. This account will be foundational for much philosophical poetry and prose in the Middle Ages. Philosophia begins her account with the assertion that the generation and process of all of mutable nature in terms of its cause, order and form are derived from the divine Mind. The origination of these is called Providence. The procession of this order in time is called Fate. As he puts it, “this order of fate proceeds from the simplicity of Providence.” Fate is the instrument of this Providence, and is aided in this by all powers, heavenly and earthly.

The personification of Nature as a “Goddess” has to be taken seriously. It is a reflection of two separate traditions. First, it reflects the tradition of the Greek thought of a cosmic goddess of infinite life. This poetic tradition will receive new life in twelfth-century works such as the De mundi universitate of *Bernard Silvester and Alain de Lille’s De planctu naturae and Anti-Claudianus.

Pseudo-Dionysius is important in that he leads medieval thinkers to think of nature as “being” or what is, and of God as “super-essential,” that is, beyond being. God is the transcendent ineffable One; being, or what is, is subject to the examination of reason.

It is with Eriugena that one finds a philosophical synthesis of Augustine, Boethius, and Pseudo-Dionysius. In this sense, he is a foundational source for the thinking about nature in the Middle Ages. The very title of Eriugena’s major work, Peri Physeon (De divisione naturae) echoes Greek concerns with Nature as such. For him, nature does not mean just “this or that” thing, but Nature as a whole including God. John O’Meara’s paraphrase of this division provides a useful summary:

“The first and fundamental division of all things which can be grasped by the mind or lie beyond its grasp is into those things that are and those that are not. Nature is the term we apply to all things, to those that are and to those that are not. Nature is a genus that is divided into four species: that which creates and is not created, that which is created and also creates, that which is created but does not create, and that which neither creates nor is created. The third species is the contrary of the first, as the fourth is of the second. The fourth species is classed among the impossibles, since it is of its essence that it cannot be. The first species is the Cause of all things that are and that are not, that is, God; the second is the primordial causes; and the third those things that become manifest through coming into being in times and places.”

In this way, Nature is worked into a Christian-Platonic understanding of the world. The first and fourth division is God as Source and End. The second is the Primordial Causes as creative, and the third is “created natures” including the human being. Elsewhere, Eriugena presents the human being as “the workshop” of nature in which the human intelligence re-creates nature on its way back to the One. This broad philosophical concept of Nature would provide the background for much poetry and philosophy at least up until the burning of Eriugena’s book in Paris in 1210, and would continue to have a lasting influence on the “greater philosophers” including Aquinas, Eckhart, and Nicholas of Cusa, not to mention the great Latin poets of the Middle Ages.

It is in the twelfth century, however, that one witnesses a re-birth of a concern with Nature in Poetry and in Philosophy. This re-birth is commonly associated with the Neo-Platonism of the School of Chartres. This re-birth reintroduced ideas of nature from Latin pagan writers such as Macrobius, Chalcidius, Martianus and others.

This “Chartrian” notion of nature presents the world as a macrocosmos and the human being as a microcosmos. The study of the macrocosmos will reveal the nature of the microcosmos, the human being. Hence it is not surprising that early reviewers of the De mundi universitate of Bernard Silvester accused that work of paganism. In this allegorical fable (integementum), Bernard provides a synthesis of pagan and Christian worlds. Still, the Neoplatonic influence is evident throughout the poem. Nature is described as “maker” (artifex). She is the one who provides bodies for the souls that derive from Noys (the divine mind). Nature is an intermediary between the supra-lunary world of the heavens with the divine mind and the created bodies in this world. This notion of nature as the mediator between the heavens and bodies, and between souls and bodies will have a long influence. Even the introduction of the more “naturalistic” *Aristotelianism of the schools in the thirteenth century will not deflect its influence. It will simply be absorbed by it. Further, this Neoplatonic vision of nature will be revived in the later Renaissance by the greatest Platonist of the age, Marsilio Ficino. The application of this idea to nature will become very evident in his work, De vita libri tres.

It is a common claim that Alain de Lille made “the single most significant contribution to the history of the goddess Natura in medieval literature” (George D. Economou). In the De planctu naturae, modeled after Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, the goddess Natura appears to the poet in a vision. Again, as in the tradition mentioned above, her task is to give order and structure to the production of mutable things. She is the vice-regent of God, responsible for the generation of things. The very costume of Natura details her heavenly origin and her regency over the created world where she is responsible for the generation of the human being as the image of the macrocosm. She is the vicar of God. The Law of Nature, thus, reflects the eternal law of God. Hence, she advocates marriage as the proper end of human generation, and condemns man’s subversion of her laws in sodomy.

The task of the Anti-Claudianus is to set out the creation of a new human being who by means of an imitation of Christ will re-create nature and return it to its end, God as fulfillment. This work involves a cosmic journey, the normal human struggles for moral perfection, and man’s place in the universe. This debate on nature and sexual love is of course expressed with great skill in Jean de Meun’s Roman de la Rose. Indeed, it closely parallels the poems of Alain de Lille. Nature is again seen as the vicar of God, the one responsible for implementing the order of nature. This tradition of the “Goddess Nature” will later be depicted in *Chaucer’s Parlement of Fowles.

Yet soon after the work of Bernard Silvester and Alain de Lille, a new approach to nature presented itself to Latin readers. With the translation into Latin of works on *astronomy and *astrology such as the Introduction to Astronomy by *Abu Ma‘Shar (Albumasar), Latin readers now found that advances in cosmology had been achieved in the Islamic world. And yet the reference to a divine source of order is not absent from these works. These works would become an integral part of the twelfth- and thirteenth-century translations of Aristotle.

The introduction of Aristotle to the curriculum of the medieval university took place between 1150 and 1260. By 1255, candidates for the M.A. degree at Paris were required to read the texts of the Stagarite. And by 1267 *Roger Bacon in his Communia naturalium will boast that natural philosophers no longer believe in “the world-soul” or such mythological belief. This marked a profound change in the approach to the concept of Nature. Nature is no longer seen as a “goddess.” Nature is now a structure with rational properties that can be scientifically understood. And with the use of instruments, the human being can examine all of the heavens and the Earth. Nature is a stable present order subject to investigation by reason and will of human action. This new Aristotelian concept of Nature has very distinctive characteristics.

Nature in the Aristotelian sense is defined in reference to two other concepts, Art (techne) and Chance (tuche). These two concepts continued to influence the understanding of nature throughout the Middle Ages. In certain respects, the issue of Art versus Nature referred back to fundamental issues in Greek Philosophy. Gregory Vlastos in Plato’s Universe outlines the manner in which, for Plato, Art triumphs over Nature as a principle of change. And yet the recovery of Aristotle in the thirteenth century and later helped recover elements of the importance of Nature as a principle of motion and rest. Yet this would have to be integrated with Augustine’s interpretation of divine ideas, where Art came to be fundamentally identified with the creative primordial causes. Hence, due to Art, Nature was the expression of the divine plan.

Following on the recovery of Aristotle, the word Nature had multiple meanings. These meanings are tied to the technical uses of the term physis/natura in Aristotle. He acknowledges that phusis with a long u signifies the growth or coming to be of things. From the observation of living things, nature came to be used as the active principle of growing things. This meaning was extended to become the technical term, nature, as the source of movement or the active principle of movement in all natural things. But Aristotle also identifies nature with the matter involved in growth, that out of which natural things come. Again, nature came to be applied to the structure/form and composition of natural things. Aristotle’s criticism of the pre-Socratics, much echoed in the texts of medieval natural philosophers, attacked their reduction of form to matter. Again, the term nature was extended to mean every essence. Nevertheless, despite the multiple meanings, the medieval thinkers are very precise about the use of the term. Hence, whereas the modern meaning of the term Nature is very loose, possibly signifying the sum total of things, a manifold, the medieval connotations of the term, like the ancient connotations, are varied.

One must not forget, however, that the concept of Nature that medieval Latins received is filtered through the commentaries of Islamic philosophers, in particular those of Avicenna (*Ibn Sina) and Averroes (*Ibn Rushd). This interpretation lends a strongly necessitarian and deterministic reading of the order of nature in the light of the executive will of God. And as in *Abu‘Mashar, the reference to a feminine role in the development of nature is not absent.

What then is the fundamental shift of meaning from the Platonism of the twelfth century to the Aristotelianism of the thirteenth century with respect to the Concept of Nature? James Weisheipl puts the matter succinctly:

“The fundamental assumption in the Aristotelian conception of nature is that natural phenomena, that is, those arising from neither Art nor Chance, are intelligible; there is a regularity, a determined rationality, about these phenomena which can be grasped…. Therefore, we must admit that in each physical reality there is something given in experience, which is none other than the spontaneous manifestation of its characteristics and proper activities. There is nothing ‘behind’ this spontaneity, as far as the body is concerned; it is just ‘given’ in experience. Thus, it will follow that Nature will have active and passive principles.”

Following on this will be the fundamental distinction between natural agency/bodies and artificial agency/bodies. But even here, qualifications are called for. Through various sources, especially Augustine, Stoic doctrines of matter as having an active element were integrated with the Aristotelian doctrine of matter so that matter was not seen by all natural philosophers in the Middle Ages as a purely passive principle. This is especially the case for the Franciscan tradition.

It would appear now that what had previously been reserved to creative divine ideas or art, is now seen as also the prerogative of the human being. Artificial production is the result of the idea in the mind of the human being even though the idea has its ultimate source in the mind of God. Finally, nature as matter signifies not only pure passivity but all the passive powers in nature. Nature as form was the principle of spontaneous activity.

This division of nature would have significant consequences for the male/female distinction and for issues of gender throughout the Middle Ages. It would influence all assumptions about the internal powers of male and female. Prudence Allen has studied this issue carefully. She begins her account with one of the earliest teachers of natural philosophy, Roger Bacon. He is seen as a representative of the position of sex-neutrality. Both men and women share the same rationality. Further, he states that he is following the example of *Robert Grosseteste in not simply accepting what Aristotle said as the truth. Aristotle is a wise man “but nevertheless, he did not reach the limit of wisdom….” In his theory of generation, Bacon offers a scientific explanation, and emphasizes the role of the heavenly bodies. Unlike Bacon, the main tradition of Paris, based on *Albertus Magnus, and represented by *Thomas Aquinas and *Giles of Rome, stresses the polarity of the sexes. Allen acknowledges the central role that the texts of Giles played even in the Faculty of Medicine.

The Aristotelian revolution brought about a more diversified concept of nature. This had very significant impact on various scientific fields from the study of the elements to sensation to human knowledge. And yet it is significant that the sex neutrality position of a Roger Bacon gave way over time to the more popular view of sex polarity. As Allen puts it, Aristotle’s views on nature and generation influenced all levels of education and practice in the Middle Ages.

One major consequence of this Aristotelian definition of nature was the gradual disappearance of the sex complementarity view associated with twelfth-century women writers such as Roswitha, Héloïse, and Herrad. In brief, something as seemingly abstract as the Concept of Nature had fundamental practical implications for even the most intimate details of life and the organization of human education and relations.

One also witnesses a new concern with the “manipulation” of nature on the part of some philosophers and scientists such as Roger Bacon and Pierre de Maricourt (*Peter Peregrinus) c. 1267. Emphasis is placed on the work of the hand in the construction of a compass, the uses of magnets, the calculation of distances with instruments, and the building of optical means for extending vision. Alongside this new concern with the “manipulation” of nature, one notices a new concern with setting out the boundaries of an Art and Science of Nature. In other words, just as Logic provides the rules for correct argumentation, the experimentalist will have need of a practical logic or method. The function of this logic will be to distinguish the art and science of Nature from Magic, and also from other human pursuits such as morals and religion. While there is evidence in both Roger Bacon and Pierre de Maricourt of actual experimentation and the construction of artificial experiments, one must be cautious about general claims concerning flying machines and submarines. These latter belong to the utopian realm of fiction, and are not original with Roger Bacon. Still, it is clear that in the mid-thirteenth century, influenced by actual contacts with the world of Islam, the Latin West came to have a sense that natural science was a pursuit that would require the mastery of the problems presented to it by two of the great scientists of the ancient world, Aristotle and Ptolemy. Indeed, they already see that Islamic scientists such as *Ibn al-Haytham decisively advance the study of vision and light, and present them with new models for scientific advancement.

While it is true that Petrarch introduces a new humanistic concern with nature, it is clear also that the medieval image of Nature as feminine “Goddess,” as the personification of divine Wisdom, and as the one responsible for the production of things through generation continues to have an influence into the late Renaissance. Katherine Park has demonstrated that a new image of Nature, one quite distinct from the medieval image, begins to appear in the 1470s at Naples. It was the result of a collaboration between the Roman scholar Luciano Fosforo and the miniaturist Gaspare Romano in the illustrations of a manuscript copy of Pliny’s Natural History for Cardinal John of Aragon. This new image “of Nature as a lactating woman, partly or completely naked, or as a woman endowed with many breasts” would have a marked influence on Renaissance perceptions of Nature and would in part replace the medieval image of Nature as divine “Goddess,” organizer of the production of generated things.

We have seen that many influences, both pagan and Christian, go into the making of the medieval concept of Nature. This concept in its many forms had a long-lasting influence into the Renaissance and even into modernity.

See also Microcosm/macrocosm; Nature: the structure of the physical world

Bibliography

Allen, Prudence. The Concept of Woman: The Aristotelian Revolution, 750 B.C.–A.D. 1250. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eeerdmans Publishing Company, 1985.

Boethius. Theological Tractates; The Consolation of Philosophy, with an English Translation of “I. T.,” Revised by H.F. Stewart. Edited by H.F. Stewart and E.K. Rand. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968.

Chenu, M.D. Nature, Man and Society in the Twelfth Century. Selected, edited, and translated by Jerome Taylor and Lester K. Little. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

Dronke, Peter, ed. A History of Twelfth-Century Western Philosophy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Economou, George D. The Goddess Natura in Medieval Literature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Hackett, Jeremiah, ed. Roger Bacon and the Sciences: Commemorative Essays. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1997.

Jeauneau, Edouard. “Lectio philosophorum”: Recherches sur l’Ecole de Chartres. Amsterdam: Hakkert, 1973.

Mensching, Günther. “Metaphysik und Naturbeherrschung im Denken Roger Bacons.” In Lothar Schäfer und Elizabeth Ströker, eds. Naturauffassungen in Philosophie, Wissenschaft, Technik [Band 1: Antike und Mittelalter]. Freiburg/München: Verlag Karl Alber, 1993.

Modersohn, Mechthild. Natura als Gottin im Mittelalter: Ikonographische Studien zu Darstellungen der person-ifizierten Nature. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1997.

Murray, Alexander. “Nature and Man in the Middle Ages.” In John Torrance, ed., The Concept of Nature [The Herbert Spencer Lectures]. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

O’Meara, John J. Eriugena. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

Park, Katherine. “Nature in Person: Medieval and Renaissance Allegories and Emblems.” In Lorraine Daston and Fernando Vidal, eds., The Moral Authority of Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Roberts, Lawrence D., ed. Approaches to Nature in the Middle Ages. Binghamton, New York: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1982.

Vlastos, Gregory. Plato’s Universe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1975.

James A. Weisheipl, O.P. Nature and Motion in the Middle Ages. Edited by William E. Carroll. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1985.

JEREMIAH HACKETT

Nature: The Structure of the Physical World

In the literature of the Middle Ages, the goddess Natura was the personification of Nature. She ruled over social relations and was the inspiration for right living according to reason. But the goddess Nature played no role in understanding the workings of nature from the standpoint of science and natural philosophy. The means of understanding nature’s operations in the physical world came to the Middle Ages with the translation of Aristotle’s works on natural philosophy in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Aristotle’s ideas about nature and the “natural” appear in almost all of his non-logical works, including those on ethics and politics, where he has much to say about human nature. His views on the role of nature in the material cosmos of our physical world, however, are revealed largely in those treatises commonly known as “the natural books,” namely Physics, On the Heavens, On Generation and Corruption, On the Soul, and Meteorology, along with his biological treatises. During the late Middle Ages, almost all scholars accepted Aristotle’s understanding of nature.

Aristotle divided the world into two radically different regions: the celestial and the terrestrial. Together, these regions comprised the whole of nature. They were assumed to form a “ladder” (the so-called “ladder of nature”), a concept based on the idea that there is a gradation of perfection and virtue in the universe ranging from the center of the Earth, the least perfect region, to the outermost sphere of the universe, the most perfect. The farther things are from the Earth, the nobler and more perfect they are. The two regions are separated at the concave surface of the lunar sphere: everything beyond forms the celestial region, everything below, the terrestrial region.

The Celestial Region

The celestial region is composed of, and everywhere filled with, an incorruptible ether. The planets and stars are made of it, as are the spheres in which they are embedded, and which carry them around perpetually with a uniform, circular motion. The only change that occurs in the celestial region is the change of position experienced by celestial bodies as they are carried round by their espective orbs. Because it was generally regarded as fitting that a nobler being should influence a less noble being, it was universally believed that the essentially incorruptible and unchanging celestial region necessarily influences and dominates the incessantly changing terrestrial region.

The Terrestrial Region

In contrast to the celestial region, the terrestrial region, which lies below the lunar sphere, consists of bodies in a perpetual state of change. These bodies are either one of the four elements—fire, air, water, and earth—or compounds composed of two or more of those elements. Every animate and inanimate body in the terrestrial region is composed of matter and form, where the matter serves as a substratum in which the form inheres. For Aristotle the form of a thing or body is expressed in its defining characteristics—the properties that make it what it is. In the terrestrial realm, nature is a collective term for all the bodies contained therein, each of which consists of matter and form. If unimpeded, each of these bodies acts in accordance with its natural potentialities. In so doing, it is capable of acting on other bodies—that is, it is capable of causing effects on them. Thus did Aristotle allow for secondary causation. He believed that every effect was produced by four causes acting simultaneously, namely a material cause, which is the thing from which something is made; a formal cause, which produces the defining characteristics of a thing; an efficient cause, which is the agent of an action; and the final cause, or the purpose for which the action is undertaken. These four causes are capable of producing four kinds of change or motion: substantial change occurs when something comes into being or passes out of existence; qualitative change is the alteration of something, as when its color changes, or it becomes harder or softer; quantitative change involves an increase or decrease in size or weight; and change of place is motion from one place to another.

In the Middle Ages, natural philosophers regarded the domain of nature as essentially that which embraced all motion and rest with respect to a body’s natural place. The concept of natural place was fundamental to their idea of nature and the key to Aristotle’s idea of what makes the natural world what it is. Aristotle believed that the terrestrial region—that is, the part of the world that lay below the concave surface of the lunar sphere and extended all the way to the center of our spherical Earth at the center of the world—was naturally divided into four concentric layers, each of which was the natural place of one of the four elements. The outermost concentric ring is that of fire; the next is that of air, beneath which is the concentric ring of water and then, at the center of the world, the sphere of Earth, the center of which coincides with the geometric center of the universe. If a body is removed from its natural place it will, if unimpeded, seek to move back to it. Thus a piece of the element earth, or a compound body in which earth is predominant, will move naturally downward toward the Earth’s center and come to rest naturally on the Earth’s surface. Similarly, a fiery body, or a compound that is primarily fire, will always, if unimpeded, rise upward toward the natural place of fire. Air and water are intermediate elements. That is, an airy body will rise upward when in earth or water and descend when in the concentric region of fire; similarly, water, or a compound body in which water is predominant, will rise when in the earth, but descend when in the natural places of fire or air.

Nature embraces the totality of things that have an innate capacity for motion. Moreover, Nature always acts for a purpose in order to achieve some goal or end. For example, a heavy body that falls to Earth does so in order to come to rest in its natural place on the Earth’s surface. By their very natures, animate and inanimate bodies always act to acquire their respective defining forms, that is, to become in actuality what they had previously been only potentially, as when a child grows into an adult or a seed develops into a plant. Aristotle regarded such natural transformations as substantial changes.

Nature does not act with a conscious purpose. No God or Divine Mind causes the changes in nature. All things that change have an innate capacity for reaching their goals or ends. This was acceptable to Christians, who assumed that God had created the world and ordained Nature with the powers and capacities to act in the manner that Aristotle had described. Although God could, and did, create miracles that are contrary to the natural order, He rarely did so. The Aristotelian concept of cosmic nature, with its two radically different parts that were held together by a “ladder” rising from the least noble and perfect beings to the most noble and perfect, was abandoned with the rejection of scholastic natural philosophy in the seventeenth century.

The scholastic natural philosophers who described and investigated nature did so largely by abstract, non-empirical means, and with preconceived ideas about the way the universe ought to operate. Although, like Aristotle, they emphasized the empirical foundations of knowledge, their analyses and interpretations were not based on careful observations. Theirs was an “empiricism without observation,” and ultimately a “natural philosophy without nature.” By the seventeenth century, natural philosophers abandoned this approach, seeking instead actually to observe the operations of the real, physical world.

See also Aristotelianism; Cosmology; Nature: diverse medieval interpretations

Bibliography

Cadden, Joan. “Trouble in the Earthly Paradise: The Regime of Nature in Late Medieval Christian Culture.” In Lorraine Daston and Fernando Vidal, eds. The Moral Authority of Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004, pp. 207–231.

Dales, Richard C. The De-animation of the Heavens in the Middle Ages. Journal of the History of Ideas (1980) 41: 531–550.

Grant, Edward. Medieval and Renaissance Scholastic Conceptions of the Influence of the Celestial Region on the Terrestrial. Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies (1987) 17: 1–23.

———. Planets, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos 1200–1687. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

———. “Medieval Natural Philosophy: Empiricism Without Observation.” In Cees Leijenhorst, Christoph Lüthy, Johannes M. M. H. Thijssen, eds. The Dynamics of Aristotelian Natural Philosophy from Antiquity to the Seventeenth Century. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2002, pp. 141–168.

Murdoch, John E. “The Analytic Character of Late Medieval Learning: Natural Philosophy Without Nature.” In Lawrence D. Roberts, ed., Approaches to Nature in the Middle Ages. Binghampton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1982, pp. 171–213.

EDWARD GRANT

Navigation (Arab)

The Arabian Peninsula, surrounded by the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian (or Persian) Gulf, had a geostrategic position in relations between East and West. Before the beginning of Islam in 622 the Arabs had had some nautical experience which was reflected in the Qur’an (VI, 97: “It is He who created for you the stars, so that they may guide you in the darkness of land and sea”; XIV, 32: “He drives the ships which by His leave sail the ocean in your service”; XVI, 14: “It is He who has subjected to you the ocean so that you may eat of its fresh fish and you bring up from it ornaments with which to adorn your persons. Behold the ships plowing their course through it.”) and in ancient poetry (some verses of the poets Tarafa, al-A‘sha’, ‘Amr Ibn Kulthum, and others). Arabs used the sea for transporting goods from or to the next coasts and for the exploitation of its resources (fish, pearls, and coral). However, their experience in maritime matters was limited due to the very rugged coastline of Arabia with its many reefs and was limited to people living on the coast. Because they lacked iron, Arab shipwrights did not use nails, but rather secured the timbers with string made from palm tree thread, caulked them with oakum from palm trees, and covered them with shark fat. This system provided the ships with the necessary flexibility to avoid the numerous reefs. The Andalusi Ibn Jubayr and the Magribi Ibn Battuta confirm these practices in the accounts of their travels that brought them to this area in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, respectively. Ibn Battuta also notes that in the Red Sea people used to sail only from sunrise to sunset and by night they brought the ships ashore because of the reefs. The captain, called the rubban, always stood at the bow to warn the helmsman of reefs.

The regularity of the trade winds, as well as the eastward expansion of Islam, brought the Arabs into the commercial world of the Indian Ocean, an experience that was reflected in a genre of literature which mixes reality and fantasy. Typical are the stories found in the Akhbar al-Sin wa-l-Hind (News of China and India) and ‘Aja’ib al-Hind (Wonders of India), as well as the tales of Sinbad the Sailor from the popular One Thousand and One Nights. But medieval navigation was also reflected in the works of the pilots such as *Ahmad Ibn Majid (whose book on navigation has been translated into English) and Sulayman al-Mahri.

In the Mediterranean Sea

The conquests by the Arabs of Syria and Egypt in the seventh century gave them access to the Mediterranean, which they called Bahr al-Rum (Byzantine Sea) or Bahr al-Sham (Syrian Sea). Nautical conditions were very different in this sea: irregular but moderate winds, no heavy swells, and a mountainous coastline that provided ample visual guides for the sailors on days with good visibility. The Arabs took advantage of the pre-existing nautical traditions of the Mediterranean peoples they defeated. In addition, we have evidence for the migration of Persian craftsmen to the Syrian coast to work in ship building, just as, later on, some Egyptian craftsmen worked in Tunisian shipyards.

The Arab conquests of the Iberian Peninsula (al-Andalus) and islands such as Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus set off a struggle between Christian and Muslim powers for control of the Mediterranean for trade, travel, and communications in general. Different Arab states exercised naval domination of the Mediterranean, especially during the tenth century. According to the historian Ibn Khaldun, warships were commanded by a qa’id, who was in charge of military matters, armaments, and soldiers, and a technical chief, the ra’is, responsible for purely naval tasks. As the Arabs developed commercial traffic in Mediterranean waters, they developed a body of maritime law which was codified in the Kitab Akriyat al-sufun (The Book of Chartering Ships). From the end of the tenth century and throughout the eleventh, Muslim naval power gradually began to lose its superiority.

In navigation technique, the compass reached al-Andalus by the eleventh century, permitting mariners to chart courses with directions added to the distances of the ancient voyages. The next step was the drawing of navigational charts which were common by the end of the thirteenth century. Ibn Khaldun states that the Mediterranean coasts were drawn on sheets called kunbas, used by the sailors as guides because the winds and the routes were indicated on them.

In the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa, despite their marginal situation with respect to the known world at that time, had an active maritime life. The Arabs usually called this Ocean al-Bahr al-Muhit (“the Encircling or Surrounding Sea”), sometimes al-Bahr al-Azam (“the Biggest Sea”), al-Bahr al-Akhdar (“the Green Sea”) or al-Bahr al-Garbi (“the Western Sea”) and at other times al-Bahr al-Muzlim (“the Gloomy Sea”) or Bahr al-Zulumat (“Sea of Darkness”), because of its numerous banks and its propensity for fog and storms. Few sailors navigated in the open Atlantic, preferring to sail without losing sight of the coast. The geographer *al-Idrisi in the middle of the twelfth century informs us so: “Nobody knows what there is in that sea, nor can ascertain it, because of the difficulties that deep fogs, the height of the waves, the frequent storms, the innumerable monsters that dwell there, and strong winds offer to navigation. In this sea, however, there are many islands, both peopled and uninhabited. No mariners dare sail the high seas; they limit themselves to coasting, always in sight of land.” Other geographers, including Yaqut and al-Himyari, mention this short-haul, cabotage style of navigation. Yaqut observes that, on the other side of the world, in the faraway lands of China, people did not sail across the sea either. And al-Himyari specifies that the Atlantic coasts are sailed from the “country of the black people” north to Brittany. In the fourteenth century, Ibn Khaldun attributed the reluctance of sailors to penetrate the Ocean to the inexistence of nautical charts with indications of the winds and their directions that could be used to guide pilots, as Mediterranean charts did. Nevertheless, Arab authors describe some maritime adventurers who did embark on voyages of exploration.

Fluvial Navigation

Only on the great rivers such as the Tigris, the Euphrates, the Nile and, in the West, the Guadalquivir was there significant navigation. It was common to establish ports in the estuaries of rivers to make use of the banks to protect the ships.

Nautical Innovations

Two important innovations used by the Arabs in medieval period are worthy of mention: the triangular lateen sail (also called staysail), and the sternpost rudder. The lateen sail made it possible to sail into the wind and was widely adopted in the Mediterranean Sea, in view of its irregular winds. The Eastern geographer Ibn Hawqal, in the tenth century, described seeing vessels in the Nile River that were sailing in opposite directions even though they were propelled by the same wind. To mount only one rudder in the sternpost which could be operated only by one person proved vastly more efficient that the two traditional lateral oars it replaced. Although some researchers assert that this type of rudder originated in Scandinavia and then diffused to the Mediterranean Sea, eventually reaching the Arabs, it is most likely a Chinese invention which, thanks to the Arabs, reached the Mediterranean.

Toward Astronomical Navigation

The Arabs made great strides in astronomical navigation in the medieval period. With the help of astronomical tables and calendars, Arab sailors could ascertain solar longitude at a given moment and, after calculating the Sun’s altitude as it comes through the Meridian with an astrolabe or a simple quadrant, they could know the latitude of the place they were in. At night, they navigated by the altitude of the Pole Star. For this operation Arab sailors in the Indian Ocean used a simple wooden block with a knotted string called the kamal which was used to take celestial altitudes. They also knew how to correct Pole Star observations to find the true North. Ibn Majid, for example, made this correction with the help of the constellation called Farqadan, which can only be seen in equatorial seas.

The determination of the longitude was a problem without a practical solution until the invention of the chronometer in the eighteenth century. Arab sailors probably may have used a sand clock to measure time, because they knew how to produce a type of glass that was not affected by weather conditions. So they could estimate the distance that the ship had already covered, even though speed could not be accurately determined. The navigational time unit used was called majra, which the geographer Abu l-Fida’ defines as “the distance that the ship covers in a day and a night with a following wind,” a nautical day that it is the rough equivalent of one hundred miles.

See also Columbus, Christopher; Fishing; Shipbuilding; Transportation; Travel and exploration

Bibliography

Fahmy, Aly Mohamed. Muslim Naval Organisation in the Eastern Mediterranean from the Seventh to the Tenth Century A.D. 2 vols. Cairo: General Egyptian Book Organisation, 1980.

Lewis, Archibald Ross. Naval Power and Trade in the Mediterranean, A. D. 500–1000. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951.

Lirola Delgado, Jorge. El poder naval de Al-Andalus en la época del Califato Omeya. Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1993.

Picard, Christophe. La mer et les musulmans d’Occident au Moyen Age. VIIIe-XIIIe siècle. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1997.

Pryor, John H. Geography, Technology and War. Studies in the Maritime History of the Mediterranean, 649–1571. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Tibbetts, G. R. Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean before the Coming of the Portuguese being a translation of Kitab al-Fawa’id fi usul al-bahr wa’l-qawa’id of Ahmad b. Majid al-Najdi. London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1971.

JORGE LIROLA

Nequam, Alexander

Alexander Nequam (also known as Neckam or Neckham) (1157–1217) was born and brought up in St. Albans, England. He studied in Paris at the school of the Petit Pont, c. 1175–1182, before returning to England in 1183. He then taught for a year at Dunstable and then at St. Albans before teaching at Oxford from c. 1190. Sometime between 1197 and 1202 he became a canon at the Augustinian abbey of Cirencester. While Nequam never wrote any formal treatise on natural science, his writings are informed by a strong sense of observation of the natural world. His De nominibus utensilium, a list of words intended to teach vocabulary to schoolchildren, was modelled on the Phale totum or De utensilibus of Adam of Petit Pont. It uses everyday examples, such as household utensils, food, houses and furniture, cooking, parts of a castle, and the farm. Among his references to ships is the earliest known reference to a compass with a magnetized needle that revolved until it pointed north. Nequam’s work provides a vivid insight into everyday life in the late twelfth century.

Much of Nequam’s writing is concerned with grammatical and moral issues. His most widely copied work, the Corrogationes Promethei, deals with figures of speech and literary constructions, updating the instruction provided by Donatus and Priscian. A second section deals with difficult words in the Bible. His Sacerdos ad altare is similar to De nominibus utensilium in form, but deals with clerical matters. It draws on a wide range of classical works, including the Bucolics and Georgics of Virgil, and the epigrams of Martial, which were not widely read in the twelfth century. Nequam uses edifying stories to preach against any false sense of moral superiority.

His interest in scientific matters is evident in his De naturis rerum et in Ecclesiasten. He is one of the first known scholars to show awareness of scientific texts newly translated from both Arabic and Greek. He incorporates quotations from pseudo-Avicenna, De caelo et mundo, as well as from Aristotle’s Ethica, and the Liber XXIV philosophorum and Liber de causis, translated by *Gerard of Cremona. He seems to have derived his knowledge of these texts not from his studies in Paris in the 1170s, but from his contacts at Oxford, perhaps from Englishmen such as Daniel of Morley and *Alfred of Sareschel, who had travelled in Spain. Alexander makes use of medical writings from *Salerno, especially De commixtionibus elementorum by *Urso of Calabria, the Tegni of *Galen, the De dietis universalibus of Isaac, the Pantegni of Constantine the African, and the Quaestiones naturales of *Adelard of Bath. Like Gerald of Wales (1175–1204), another source of information about animals, Alexander Nequam draws his natural science both from ancient authors such as Isidore, Solinus, and Cassiodorus, and from his own observation. In the De naturis rerum and the Laus sapientiae divinae, a metrical version of the same treatise, Alexander develops the theme that examining the works of nature leads to the love of God. The Laus sapientiae divinae deals with the stars, the rivers of Europe, the theory of the elements, and the three parts of the world. In the Suppletio defectuum, a supplement to the Laus sapientiae divinae, he describes birds, trees, herbs, birds, and animals, giving each of them a moral significance. In a second section, he deals with creation as a whole, then with the problems of man and the human soul, the Sun, Moon, and planets. Only in the final section does he deal with theology and the seven liberal arts.

Besides scriptural commentaries, Alexander wrote a major synthesis of theology, the Speculum speculationum, which was more conjectural than the Sentences of *Peter Lombard and in keeping with the philosophical reflections of St. Anselm (c. 1033–1109). Nequam frames his treatise as an attack on the false argument of the Cathars, “illiterate heretics” who distinguish between a good God and the creator of a corrupt world. His theme throughout the four books of his treatise is that God is the source of all good things, and that evil has no separate source, but rather has to be understood as the absence of good.

See also Nature: diverse medieval interpretations; Translation movements

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Alexander Nequam, De naturis rerum libri duo: with the poem of the same author, De laudibus divinæ sapientiae. Edited by Thomas Wright. Rerum britannicarum medii aevi scriptores 34. London: Longman, 1863.

———. “De nominibus utensilium.” In Anthony B. Hunt, Teaching and Learning Latin in Thirteenth-Century England, 3 vols. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Brewer, 1991, 1: 177–190.

———. Speculum speculationum. Edited by Rodney M. Thomson. Auctores Britannici medii aevi 11. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Secondary Sources

Holmes, Urban T. Daily living in the twelfth century; based on the observations of Alexander Neckham in London and Paris. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1980.

Hunt, Richard W. The schools and the cloister: the life and writings of Alexander Nequam (1157–1217). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

O’Donnell, J. Reginald, “The liberal arts in the twelfth century with special reference to Alexander Nequam (1157-1217).” In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Age: IVe Congrès international de philosophie médiévale Montréal 1967. Paris: Vrin 1969, pp. 583–591.

Viarre, Simone. “A propos de l’origine égyptienne des arts libéraux: Alexandre Neckam et Cassiodore.” Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Age: IVe Congrès international de philosophie médiévale, Montréal 1967. Paris: Vrin, 1969, pp. 583–591.

CONSTANT J. MEWS

Niccolò Da Reggio

A Greek and Latin bilingual scholar born in Calabria, Niccolò da Deoprepio da Reggio is known as a professional translator working at the Angevin court in Naples during the period 1308–1345 (if not later). Biographical data are scant: his year of birth is unknown, but should have been sometime around 1280. Unknown also is the place where he earned a medical degree, although Bologna and Padua have been suggested. The year of his death, no better attested, is likely to have been around 1350.

The first mention of a payment for the translation of a medical text made for Charles II of Anjou (1254–1309) dates back to 1308. Niccolò then pursued his activity at the Angevin court under Robert (b. 1275, king 1309, d. 1343) and Joanna I (b. 1326, queen 1343, d. 1381). Judging from his translation of *Galen, De utilitate particularum, dated 1317, Niccolò also worked for private physicians. In 1319, he was presented to the Naples Studium for a doctorate and a teaching licence. In 1322, he traveled to the papal court of Avignon under John XXII (b. 1249, pope 1316, d. 1334) as king Robert’s physician, and in 1331 he was sent to Constantinople by the king on a diplomatic mission to the Byzantine emperor Andronicus III Palaiologos (b. 1297, emperor 1328, d. 1341), from whom Robert later received a Greek Galen manuscript as a gift.

At the Angevin court, Niccolò was not the only translator, but he was the most productive. He specialized in translating Galenic treatises from Greek into Latin, with more than sixty translations. They covered many fields of Galen’s production: commentaries on Hippocratic works (Commentarii in Hippocratis Aphorismos, 1314); philosophy, epistemology, and logic (e.g., De praecognitione, perhaps translated from the manuscript offered by Andronicus III; De historia philosophorum and De subfiguratione empirica, both dated 1341; De causis procatarticis, and De substantia virtutum naturalium, which is a part of De propriis placitis); anatomy (e.g., Anatomia matricis, Anatomia oculorum, and De utilitate particularum, dated 1317); physiology (e.g., De utilitate respirationis, translated before 1309, and De causis respirationis); pathology (e.g., De passionibus uniuscuisque particule, made in 1335 or 1336 from the manuscript received by Robert from the Byzantine emperor; De temporibus paroxismorum seu periodorum, De temporibus totius egritudinis, and De tumoribus); diagnosis and prognosis (e.g., De pronosticatione); surgical therapeutic methods (e.g., De flebotomia, translated before 1309); pharmaceutical therapy (e.g., De compositione medicamentorum secundum locos, in 1335 or 1336; Sex ultimi [libri] de simplici medicina; De virtute centauree; De tyriaca); and diet (De subtiliante diaeta).

Niccolò’s program aimed at revising and achieving the program of assimilation of ancient medicine, particularly Greek, previously carried out by such previous translators as *Constantine the African (d. after 1085) at *Monte Cassino, *Burgundio of Pisa (c. 1110–1193), *Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–1187) in *Toledo, *Pietro d’Abano (c. 1257–c. 1315), and *Arnau de Vilanova (c. 1240–1311) in Montpellier. To this end, Niccolò translated neither Arabic works, nor Arabic versions of Greek texts (as did Constantine the African, Gerard of Cremona, and Arnau de Vilanova, for instance), but the original Greek texts (as Burgundio of Pisa and Pietro d’Abano already did). Not only did he complete translations left incomplete by such translators as Pietro d’Abano, but also he translated anew Galenic treatises previously translated, and he rendered into Latin works that had not been translated before. He also translated some Greek non-medical texts.

Niccolo da Reggio’s translation technique consisted in proceeding “de verbo ad verbum, nichil addens, minuens vel permutans.” It has been differently appreciated. D’Alverny, stressing that such method was that of all previous translators from Greek, considered that it led him to literally follow the original text and to adopt Greek technical terms (by transliterating rather than translating them) when he found them adequate. Furthermore, on the basis of his prefaces, she thought that he was a mediocre Latinist. Editors of Galen’s Greek works translated by Niccolò, such as for example V. Nutton, concluded that Niccolò “developed an accurate method and technical vocabulary whereby to express even the smallest features of the Greek original.” It seems, however, that such a method did not always produce understandable texts for non-Greek speakers.

Niccolò strongly contributed to the reintroduction, diffusion, and assimilation of Galenic writings and medicine into Western medicine, as the manuscript tradition of his translations indicates. His translations probably reached southern France: according to Montpellier physician *Guy de Chauliac (c. 1290–c. 1367/1370), Niccolò sent some of his translations to the papal Curia in Avignon (Inventarium sive Chirurgia magna, capitulum singulare). In the Renaissance, some of Niccolò’s translations were printed as early as 1490 in the Venice edition of Galen. Several editions appeared during the sixteenth century.

See also Translation movements; Translation norms and practice

Bibliography

Calvanico, R. Fonti per la storia della medicina e della chirurgia per il regno di Napoli nel periodo Angioino. Naples: L’Arte tip., 1962, p. 128.

D’Alverny, M.-Th. Pietro d’Abano traducteur de Galien. Medioevo (1985) 11: 19–64, pp. 41–46.

Deichgräber, K. Die griechische Empirikerschule. Berlin: Weidmann, 1965, pp. 7–11.

Dürling, R.J. A chronological census of Renaissance editions and translations of Galen. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes (1961) 24: 229–305.

———. Corrigenda and addenda to Diels’ Galenica. Traditio (1967) 23: 461–476.

Larrain, C. J. Galen, De motibus dubiis: die lateinisch Übersetzung des Niccolò da Reggio. Traditio (1994) 49: 171–233.

Lo Parco, F. Niccolò da Reggio, antesignano del risorgimento dell’antichità ellenica nel secolo XIV, da codici delle biblioteche italiane e straniere e da documenti e stampe rare. Atti della Reale Accademia di Archeologia, Lettere e Belle Arti di Napoli (1910) 5.11: 243–317.

Nutton, V. Galen, On prognosis. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1979, pp. 23–34.

———. Galen, On my own opinions. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1999, pp. 33–37.

Pezzi, G. “La vita e l’opera di maestro Nicolao da Reggio.” In Atti della IX Biennale della Marca e dello studio Firmano per la storia dell’arte medica. Fermo: Benedetti e Pauri, 1971, pp. 229–233.

Russo, P.F. Medici e veterinari calabresi. Naples: s.n., 1962, pp. 71–102.

Thorndike, L. Translations of works of Galen from the Greek by Niccolo da Reggio (c. 1308–1345). Byzantina Metabyzantina (1946) 1: 213–235.

Weiss, R. The translators from Greek of the Angevin court of Naples. Rinascimento (1950) 1: 195–226.

Wille, I. Ueberlieferung und Uebserstezsung. Zur Uebersetzungtechnik des Nikolaus von Rhegium in Galen’s Schrift De temoribus morborum. Helikon (1963) 3: 259–272.

ALAIN TOUWAIDE

Nicholas of Salerno

Very little is known about the physician and teacher Nicholas of Salerno (fl. c. 1150), but his putative authorship of the Antidotarium Nicolai, one of the most influential *pharmaceutical handbooks produced in the medieval West, makes him a convenient point of reference for a broader discussion of the complex traditions of Salernitan drug lore. The Antidotarium has also been ascribed to Nicholas of Aversa, to the Byzantine writer Nicholas Myrepsos (fl. c. 1300), to Nicholas Prepositus, and to one Nicolaus Alexandrinus: however, the inclusion in the Antidotarium of a recipe for vomitus noster (“our emetic”), which apparently corresponds to the vomitus Nicolai cited by Master Salernus in his Compendium (c. 1155–1160) argues for the existence of Nicholas of Salerno, and his authorship of the Antidotarium.

The Antidotarium Nicolai is an alphabetically organized manual containing recipes for compound remedies, based on an eleventh-century Salernitan compendium, the Antidotarius magnus. The Antidotarius magnus had a number of drawbacks: it was unwieldy (more than one thousand entries), and the recipes, drawn from a variety of ancient, early medieval, and early Salernitan sources, often appeared in numerous variant forms. Taking his cue from the anonymous commentary in the Antidotarius entitled Liber iste, Nicolas selected about one hundred ten to one hundred fifteen of the most commonly used and useful compounds (he refers to them in the preface as the usuales medicinae), to which he added a few original preparations of his own, e.g., the vomitus noster. Later versions expanded the number of recipes to about one hundred seventy-five. He laid out the entries in a broadly standardized manner: an explanation of the name of the drug is followed by its therapeutic indication, ingredients, mode of preparation, dosage, and form of administration. Nicholas equipped his manual with an index of synonyma, which contributed to rationalizing the nomenclature of materia medica, and added information on preserving drug substances. Above all, he clarified and standardized the system of apothecary measures used in the Antidotarius magnus, notably by introducing the “grain” (granum, the weight of a grain of wheat, or one-twentieth of a scruple), a small unit which allowed the recipes to be made up with precision, but in modest quantities suitable for an individual physician’s practice or apothecary’s shop. All these innovations made the Antidotarium Nicolai the foundation document of medieval practical pharmacy.

In his preface, Nicolas indicates that his target audience is physicians: he is concerned to give them the tools to make up standard medicines at an affordable cost, and to dispense them with confidence. Its virtues were immediately appreciated: Salernitan writers on practical medicine, such as the author of the “First Salernitan Gloss” on the surgery of *Roger Frugard, were already citing the Antidotarium by the 1190s. The book’s potential as a teaching tool inspired a commentary composed probably in the third quarter of the twelfth century by the Salernitan Matthaeus Platearius. Scholastic glosses continued to be produced to the end of the medieval period, e.g., by *John of Saint-Amand, and a course on the Antidotarium was obligatory for medical students at Paris by 1270–1274. Encyclopedists such as *Vincent of Beauvais (c. 1244) referred to it. At the same time, the Antidotarium began to assume the status of a standard pharmacopoeia: for example, *Frederick II of Sicily’s Constitutions of Melfi enjoined apothecaries to compound their drugs in accordance with “the antidotary,” and the apothecary ordinances of Ypres (1292–1310) named the Antidotarium as the official formulary.

It is difficult to exaggerate the long-term influence of the Antidotarium Nicolai. Extensively translated and excerpted in vernacular remedy collections (English, French, German, Dutch, Italian, Spanish, Hebrew, and even Arabic), the Latin text enjoyed a vigorous career in printed form from 1471 onward, and it continued to be issued and used down to the eighteenth century. The history of its diffusion is closely bound up with that of its logical companion-text, the Circa instans, a twelfth-century Salernitan manual of “simples” or drugs based on one (usually botanical) substance. The two are often found together in medieval manuscripts. Like the Antidotarium, Circa instans underwent considerable elaboration, and was also frequently translated. The Antidotarium Nicolai and Circa instans together bear witness to Salerno’s talent for rationalizing the subject matter of practical medicine, hence securing its domain within the Scholastic ideology of medical *scientia.

See also Herbals; Medicine, Practical; Pharmacy; Pharmacology; Salerno; Universities; Weights and measures

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Eene middelnederlandsche vertaling van het Antidotarium Nicolai met den latijnschen tekst der eerste gedrukte uit-gave van het Antidotarium Nicolai. Edited by W.S. van den Berg. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1917.

L’Antidotaire Nicolas: deux traductions françaises de l’Antidotarium Nicolai, l’une du XIV. siècle… l’autre du XV. siècle…. Edited by Paul Dorveaux. Paris: Welter, 1896.

Nicolas of Salerno. Antidotarium… Venice: Nicholas Jenson, 1471 Facsimile edition in Goltz (see below); transcription (with variant readings) in van den Berg (see below).

Un volgarizzamento tardo duecentesco fiorentino dell’Antidotarium Nicolai. Montreal, Bibliotheca Osleriana 7628. Edited by Lucia Fontanella. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, 2000.

Secondary Sources

Braekman, Willy and Gundolf Keil. Fünf mittelniederländische Übersetzungen des ‘Antidotarium Nicolai.’ Untersuchungen zum pharmazeutischen Fachschriftum der mittelalterlichen Niederlande. Sudhoffs Archiv (1971) 55: 257–320.

Goltz, Dietlinde. Mittelalterliche Pharmazie und Medizin: dargestellt an Geschichte und Inhalt des Antidotarium Nicolai: mit einem Nachdruck der Druckfassung von 1471. Veröffentlichungen der Internationalen Gesellschaft für Pharmazie, n.F, 44. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1976.

Keil, Gundolf. Zur Datierung des Antidotarium Nicolai. Sudhoffs Archiv (1978) 62: 190–196.

Lebede, Kurt-Heinz. “Das Antidotarium des Nicolaus von Salerno und sein Einfluss auf Entwicklung des deutschen Arzneiwesens. Text und Kommentar von zwei Handschriften der Berliner Staatsbibliothek.” Berlin: Diss, 1939.

Lutz, A. “Der verschollene frühsalernitanische Antidotarius magnus in einer Basler Handschrift aus dem 12. Jahrhundert und das Antidotarium Nicholai.” In Die Vorträge der Hauptsammlung der Internationalen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Pharmazie XVI, Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1960.

———. “Aus der Geschichte der mittelalterlichen Antidotarien.” In Die Schelenz-Stiftung II 1954–1972. Veröffentlichungen der Internationalen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Pharmazie n.F. 40. Stuttgart: Wissenachaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1973, pp. 115–121.

FAITH WALLIS

Noria

Noria is a generic term for a water-lifting wheel, from Arabic, na‘ura, “to groan” (from the distinctive noise made by a current-wheel revolving on its axle). There were two kinds of hydraulic wheels. The first is the current wheel, compartmented or with a rim of pots, moved by the force of the water alone, which lifted water from large rivers or irrigation canals. These wheels were mechanically simple, typically very large in size, and required no gearing. Celebrated examples are the great noria of Islamic *Toledo, driven by water from an aqueduct over the Tagus River, and the wheel at La Ñora, Murcia, driven by the current of Aljufia irrigation canal. The current-driven noria occupies a unique role in the history of technology: the first self-acting machine.

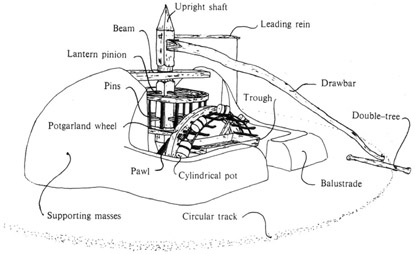

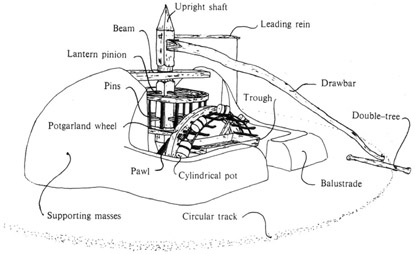

Diagram of an animal-drawn typical noria. (Thorkild Schioler)

Norias on the Orontes River at Hama, Syria. (Corbis/Charles & Josette Lenars)

The second wheel is the short-shafted, geared wheel moved by animal power. It was constructed from around two hundred separate parts, all of them wood, and so could be kept in repair by the farmer himself or a local carpenter. The animal, usually a donkey, walks along a circular track, hitched to a shaft which moved a horizontal lantern wheel which engaged teeth set in a vertical wheel which, in turn, raised the water by means of an endless chain of pots affixed to its rim with a continuous rope. The Andalusi agronomical writers mentioned this noria and suggested practical measures whereby the farmer could enhance the efficiency and longevity of his machine. Thus Abu’l-Khayr and Ibn al-‘Awwam recommended the use of hardwoods (such as olive), most likely for the teeth of the potgarland wheel, inasmuch as soft-woods were usually employed for the lantern wheel. Abu’l-Khayr prescribes the arrangement of five pots to every cubit of rope, while Ibn al-‘Awwam recommended that the pots be supplied with an air vent to prevent breakage as the force of the water pushed each pot against the wall of the well or into the pot behind it. Ibn al-‘Awwam also noted that the longer the shaft, the less force required of the animal to move the wheel; the track diameter could vary from sixteen to twenty-three feet (five to seven meters), depending on the force required.

The water raised by the noria either flowed directly into canals irrigating a field, or was stored in a tank until the farmer needed it. The tank or small reservoir (Arabic, birka; Spanish, alberca) also served to regulate the flow of water from the noria to the field. These were made of earth and were triangular in shape, with an approximate surface of 20 x 16 x 16 feet (6 x 5 x 5 m).