INTRODUCTION

1. Title

The name “Exodus” means “exit,” “departure.” In the Hebrew, this book begins with the conjunction “and”; this emphasizes that it was thought of as a continuation of Genesis and an integral part of the five books making up the first division of the Hebrew canon, the Torah (meaning “law,” “instruction,” “teaching”; GK 9368). Since the second century A.D., these first five books have been called “the Pentateuch” (i.e., “the five books”).

2. Authorship

The several internal claims that directly ascribe authorship to Moses (17:14; 34:4, 27–29; 24:4; 20:22–23:33) are supported by a strong association of Mosaic authorship with these same materials in other OT books (cf. Jos 1:7; 8:31–32; 1Ki 2:3; 2Ki 14:6; et al.). The NT writers likewise support Mosaic authorship (cf. Mk 12:26 and Ex 3:6; Lk 2:22–23 and Ex 13:2; Mk 7:10 and Ex 20:12; 21:17).

3. Date of Writing

Since Moses first became involved with leading the Israelites after his eightieth birthday (7:7), the date for the composition of the book of Exodus must fall between his eightieth birthday and his one hundred and twentieth birthday, when he died, just as the wilderness wandering was drawing to a close (Dt 34:7). Thus the approximate date for the composition rests on the date set for the Exodus from Egypt.

4. Date of the Exodus

The book of Exodus nowhere gives us enough data to link definitively biblical events with Egyptian chronology. We only know about “a new king, who did not know about Joseph” (1:8) or an anonymous “Pharaoh” (1:11, 19, 22; 2:15), or a “king of Egypt” (1:15; 2:23). It is noteworthy that “Pharaoh,” which means “great house” and designates the king’s residence and household, became, for the first time in the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, a title for the king himself. Thus, even though Ex 2:23 tells us that the king or “Pharaoh” of the oppression died and therefore could not have been the Pharaoh of the Exodus (cf. 4:19), we have no internal evidence to identify either of them specifically.

The identity of these two Pharaohs has generally centered on two views: (1) placing the Exodus under the Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1580–1321 B.C.) and (2) placing it under Pharaohs of the Nineteenth Dynasty (c. 1321–1205 B.C.). For a discussion of this issue, see either EBC, 2:288–91 or ZPEB, 2:432–36. Generally, conservative scholars have held to the earlier date for the Exodus, which is the position taken here.

5. Theology

Exodus contains some of the richest theology in the OT. Preeminently, it lays the foundation for a theology of God’s revelation of his person, redemption, law, and worship. It also initiates the great institution of the priesthood and the role of the prophet, and it formalizes the covenant relationship between God and his people.

Exodus contains detailed disclosures of the nature of God and the significance of his presence (as given by his name Yahweh [“the LORD”] and his glory). His attributes of justice, truthfulness, mercy, faithfulness, and holiness are highlighted.

God is also the Lord of history, for there is no one like him, “majestic in holiness, awesome in glory, working wonders” (15:11). Thus neither the affliction of Israel nor the plagues in Egypt were outside his control. In this book God begins to fulfill the promises that he had uttered centuries ago to the patriarchs.

The theology of deliverance and salvation is a strong emphasis of the book. The heart of redemption theology, as acknowledged by the NT (see Jn 1:29; 1Co 5:7), is best seen in the Passover narrative (ch. 12) along with the sealing of the covenant (ch. 24).

Exodus also tells us how we should live. The foundation of biblical ethics and morality is laid out first in the gracious character of God and then in the Ten Commandments and the ordinances of the Book of the Covenant.

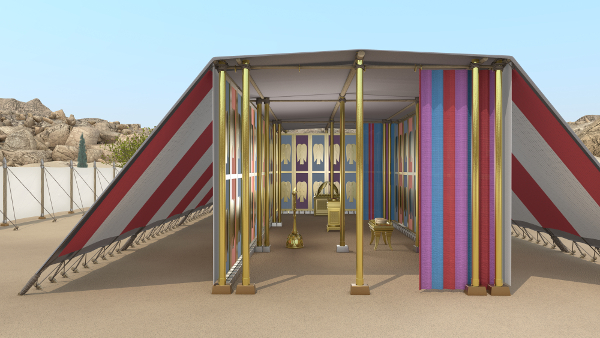

The book concludes with an elaborate discussion on the theology of worship. The tabernacle was very costly in time, effort, and monetary value; yet in its significance and function it pointed to the chief end of human beings: to glorify God and to enjoy him forever.

EXPOSITION

I. Divine Redemption (1:1–18:27)

A. Fulfilled Multiplication and Forced Eradication (1:1–22)

1. The promised increase (1:1–7)

The three prominent subjects of Exodus are (1) God’s plan for deliverance, (2) God’s guidance for morality, and (3) God’s order for worship. As the book opens, another prominent fact is immediately set forth: vv.1–7 are a virtual commentary on the ancient promise made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob about their seed (Ge 15:5; 22:17).

1–4 In the Hebrew, the book of Exodus begins with the words “And these are the names of” (which is the Heb. name for the book; cf. Ge 46:8). This is the first example of a practice common to most of the historical books of the OT: the use of the simple copulative “and” to begin a book (cf. Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 and 2 Samuel, et al.), which indicates an ongoing sequence of revelation and narration. The sons of Jacob’s wives, Leah and Rachel, are placed in order of their seniority ahead of the sons of his two concubines, except for Joseph, who is omitted because he was already in Egypt.

5 The family list in Ge 46 gives this tally: the six men of Leah had twenty-five sons and two grandsons, totaling thirty-three; the two sons of Rachel had twelve sons, totaling fourteen; Bilhah’s two sons had five sons, contributing seven to the sum; and Zilpah’s two sons had eleven sons, one daughter (apparently counted here), and two grandsons, making sixteen; therefore, thirty-three plus fourteen plus seven plus sixteen equals “seventy.” Genesis 46:26–27 starts with the figure of sixty-six (apparently dropping out Er and Onan, since they died in Canaan, as well as deleting Joseph and his two sons, since they were already in Egypt, but adding Dinah, feeling she could not be deleted). To this total of sixty-six, it added Joseph, his two sons, and Jacob himself, for a total of seventy.

6–7 With the vocabulary of God’s promised blessing of multiplication and increase as given to Adam (Ge 1:28), Noah (Ge 8:17; 9:1, 7), Abraham (Ge 17:2–6; 22:17), Isaac (Ge 26:4), and Jacob (Ge 28:3, 14; 35:11; 48:4), Moses recorded that God had been fulfilling his plan during the 430 years Israel was in Egypt.

2. The first pogrom (1:8–14)

8 The “new king” who was ignorant of Joseph’s contribution to Egypt has been variously identified. The most logical choice favors a Hyksos king. The Hyksos were foreign invaders who drove the Egyptians south and did not use Egyptian hieroglyphic writing on their scarabs. They too were Semites.

9–10 Israel was called “a people” (GK 6639) for the first time here. The situation called for an extremely delicate balance: Pharaoh needed to maintain the Israelite presence as an economic asset without thereby jeopardizing Egypt’s national security.

11 The term “masters” (sar; GK 8569) is common to both Hebrew and Egyptian. The same official Egyptian name appears on the famous wall painting from the Thebean tomb of Rekhmire, the overseer of the brickmaking slaves during the reign of Thutmose III. The painting shows such overseers armed with heavy whips. Their rank is denoted by the long staff held in their hands and by the Egyptian hieroglyphic determinative of the head and neck of a giraffe. The two storehouse cities Israel built were for the storage of provisions and perhaps armaments. The location of Pithom may be equated with Tell er-Retabeh (“Broomhill”), which some equate with Heliopolis (cf. ZPEB, 4:803–4). Rameses has most recently been located at or near Qantir (“Bridge”).

12–14 Pharaoh’s challenge—“or they will become even more numerous” (v.10)—was quite foolish in view of v.12. The result was a frightful dread that came over the Egyptians. Ironically, the God-intended instrument for the salvation of both nations (cf. Ge 12:3) became instead, through the hardness of human hearts, the source of crippling fear. Thus the Egyptians “made [Israel’s] lives bitter,” a fact later commemorated in the Passover meal’s “bitter herbs” (12:8). The emphasis of vv.8–14 falls on the “ruthlessness” of the work and servitude imposed on Israel.

3. The second pogrom (1:15–22)

15–16 The two midwives were probably representatives of or superintendents over the whole profession. The delivery stools were literally “two stones” (dual form).

17–21 The midwives “feared God” more than they feared the king of Egypt. If they were not Hebrews but Egyptians, their God-fearing ways reveal the presence of God’s common grace and the residue of earlier divine revelation that their ancestors shared but had gradually left in whole or part (cf. Ge 20:11; Dt 25:18; Mal 3:5). The midwives had respect for life, as God wanted them to have. Even though they lied to Pharaoh, they are praised for their outright refusal to take infant lives. Their reverence for life reflected a reverence for God. Thus God gave them “families.” The midwives may also have attempted to avoid answering Pharaoh’s question directly, and therefore they commented on what was true without giving all the details.

22 A single concluding and transitional verse summarizes ch. 1. Pharaoh needed to openly command by decree what had proved abortive by mere speeches. “All his people” were made agents of this crime in order to nullify the divine work of increased Hebrew children (cf. Herod’s action at the birth of Christ). Thus the third pogrom began.

B. Preparations for Deliverance (2:1–4:26)

1. Preparing a leader (2:1–10)

1–4 An unnamed couple from the family of Levi became the parents of Moses. Moses was not the firstborn, for his brother Aaron was three years older and his sister Miriam was a young girl already. That he was a “fine child” may relate to his physical appearance (cf. Ge 39:6) as well as to the qualities of his heart. When Moses’ mother could hide him no longer, she fashioned a basketlike watertight boat from papyrus reeds. Clearly, Moses’ mother had something else in mind besides child abandonment or exposure, for her actions denoted love and hope.

5 The Hebrew text does not say the royal party went “into” the river (as did Naaman in 2Ki 5:14) but that they were “at” or “by” the river, since normally royal personages did not bathe in a river. Ancient historians tell us that the waters of the Nile were regarded as sacred, and such washing was more of an ablution with its health-giving and fructifying effects.

6–9 The princess discovered the reed basket and opened it to find a beautiful Hebrew baby boy, crying. Her heart was immediately moved with compassion. Miriam emerged from her hiding place, perhaps acting as if she were just casually passing by. If her words were not according to the careful plan and instruction of her mother, then her inward prompting must have come from God—not a moment too soon or too late, with not a word too many or too few! Not only was the child returned to his own mother, but she was paid wages for nursing the child she feared she might never see alive again. Thus Moses’ mother and father had an opportunity to teach him about the God of his fathers.

10 When the Hebrew lad “grew older,” he was brought to Pharaoh’s daughter, who adopted him and named him Moses. The name is generally considered to be Egyptian, but the attached phrase—“I drew him out of the water”—points to a Hebrew origin. However, since the Egyptian princess is credited with naming him, and because of the similarity of Egyptian names such as Ptahmose, Thutmose, Ahmose, and Ramose, it is now universally regarded as Egyptian. The Hebrew root “to draw out” (GK 5406) is used perhaps because of the assonance it shared with the Egyptian name.

2. Extending the time of preparation (2:11–22)

11–12 In time Moses became aware of his Hebrew descent. When he was forty years old (Ac 7:23; cf. Heb 11:24–25), he struck and killed an Egyptian for beating a fellow Hebrew. It was his impetuosity that was wrong, not his sense of justice or his defense of the downtrodden. This cost him another forty years of education before he was ready for the task of delivering Israel. Moses’ conscience revealed that he had no legal authority to do what he did, for he first looked “this way and that” and then buried the corpse in the sand. The very impulse that led Moses to avenge wrongdoing apart from due process of law was developed to do the work of God.

13–14 The champion of the oppressed and underdogs went forth the next day—this time to settle a dispute between two of his own people. But Moses was thoroughly rebuffed and his motives impugned by the one who ought to have been practicing neighborly love. He thoroughly disarmed Moses by announcing that he knew what Moses had done on the previous day—he was a murderer, and now he was meddling in someone else’s business! Moses surmised that it must have become public information, and he wisely decided to leave Egypt as quickly as possible.

15–19 Pharaoh’s wrath was not so much to avenge the death of an Egyptian as it was to deal with his discovery that Moses was acting as a friend and possible champion of his sworn enemy, the oppressed Israelites. So Moses fled to Midian, in the Arabian Peninsula along the Gulf of Aqaba, only to be aroused by another scene of injustice. The seven daughters of a Midianite priest named Reuel were being harassed and chased from watering their flocks at the troughs by unscrupulous shepherds, but Moses rescued them. Since Moses still had his Egyptian clothing on, they judged him to be Egyptian.

20–22 The offer of hospitality led to Moses’ marriage to Reuel’s daughter Zipporah (which means “bird”; i.e., “Lady Bird”). Subsequently she gave birth to a son. Moses betrayed his loneliness by naming his son Gershom; for he explained, “I have become an alien in a foreign land.”

3. Preparing a people for deliverance (2:23–25)

23 The king of Egypt who died was probably the same one who sought Moses’ life for murdering an Egyptian (2:15; 4:19). The only pharaohs who ruled for more than thirty years in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties were Thutmose III (1483–1450 B.C.), Amenhotep III (1410–1372 B.C.), Haremhab (1349–1315 B.C.), and Rameses II (1301–1234 B.C.). Thutmose III was probably the pharaoh of the oppression who had gained control after the death of his aunt-stepmother-mother-in-law.

Misery finally found a voice, and so the pain of bodily senses of the Israelites preceded their recognition of the poverty of their spiritual condition. Thus God prepared the audience and people who would be delivered while he prepared the deliverer himself. No longer did Egypt symbolize delightful foods, wealth, and fatness; instead, it now meant slave-masters, forced labor, and bondage. So Israel cried out to God.

24–25 God was pleased to respond to even those first lisps of faith, but he was also moved by his own word that he had promised to the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Ge 17:7, 19; 35:11–12; et al.). It was a remembrance that was more than a mental act; it also included a performance of his word (cf. Ge 8:1; 1Sa 1:19). In four consecutive verbs, the divine action is charted: God heard, God remembered, God looked (i.e., considered), and God knew (i.e., was concerned).

4. Calling a deliverer (3:1–10)

1–4 While Moses was actively engaged at one task, God called him to another—the very one he had felt himself so eminently qualified for forty years earlier, when he had struck out against the abuses of power he had witnessed in Egypt.

The valley of er-Raha lay between the three summits traditionally identified with the “mountain of God” (so named in retrospect because God had appeared there). There the Lord appeared “in the form of a flame of fire.” What took place was a “strange sight” to Moses. The burning bush was not consumed; that was the miracle.

God chose the small and the despised burning bush as his medium of revelation, and he waited to see how sensitive Moses was toward the insignificant things of life before he invested him with larger tasks. The fire symbolized God’s powerful, consuming, and preserving presence (cf. 19:18; 24:17; et al.). When Moses went over to inspect this unusual sight, God issued his call by repeating Moses’ name to express the urgency of the message (cf. 1Sa 3:10).

5–6 The presence of God demanded a holistic preparation of the one who would aspire to enter his presence. Therefore, to teach Moses this lesson, God set up admittedly arbitrary boundaries—“Do not come any closer”—and commanded that he should also remove his sandals. This was to prevent him from rashly intruding into the presence of God and to teach him that God was separate and distinct from humans (cf. 19:10–13; 2Pe 1:18). Because God was present, what had been ordinary became “holy ground” and consequently “set apart” for a distinct use. The place where sheep and goats had traveled just a short time ago was transformed into “holy ground” by God’s presence. This is the first occurrence of the noun “holy” (GK 7731) in Scripture (cf. Ge 2:3 for the verb form).

When the condition for meeting God had been satisfied, he revealed himself as the “God of your father.” The collective singular “father” had a special point in that it was through the one man of promise that the many were to receive the blessing of God. Thus God assured Moses that the God of his father had not forsaken his repeated word of promise (Ge 15:1–21; 26:2–5; 35:1–12) or his people.

7–10 The anthropomorphisms of God’s “seeing,” “hearing,” “knowing” (i.e., “be concerned about”), and “coming down” are graphic ways to describe divine realities in terms of partially analogous situations in the human realm. But these do not imply that God has limitations; rather, he is a living person who can and does follow the stream of human events and who can and does at times directly intervene in human affairs.

Three times v.8 mentions the “land.” The often-repeated promise to the patriarchs was about to become a reality after over half a millennium! Two facts described the land: it was a good land and a spacious land (cf. Dt 8:7–9)—good because it was “flowing with milk and honey,” and spacious because six nations were living there. And Israel would possess it all.

The call of Moses comes to a double conclusion in vv.9–10 with the phrase “And/so now.” Verse 9 essentially repeats v.7 by summarizing the preceding speech and by restating the grounds on which this divine call is issued: namely, Israel’s present need and God’s solution. Verse 10, however, is the bottom line to the whole incident of the burning bush: It is the formal commissioning of Moses as God’s emissary to lead Israel out of Egypt.

5. Answering inadequate objections (3:11–4:17)

a. Who am I to go to Pharaoh? (3:11–12)

The first of five protests against accepting God’s commission reflects the great change that had come over Moses after forty sobering years of reflection and development. He who had been only too eager to offer himself as a self-styled deliverer earlier was now timid, unsure of himself, and devoid of any self-assertiveness that his divine commission demanded of him.

11 Moses repeated the twofold divine commission of v.10: that he should personally go to Pharaoh and that he should bring Israel out of Egypt. He prefaced this comment with the familiar idiom of the Near East that stresses the magnitude of the inequity between the agent and the mission, “Who am I?” (cf. 6:12; 1Sa 18:18; et al.).

12 God’s response to Moses was twofold: he would personally accompany him, and he would give him a sign. As God had promised fourteen times to be “with” the patriarchs Isaac and Jacob, he now assured Moses that he would be actively present as he continued to fulfill his promised word of blessing.

This “sign” (GK 253) given to Moses is confirmatory and appeals to faith rather than to immediate evidence or to the presence of the miraculous. It is not the same as Gideon’s (Jdg 6:17), for Gideon requested the sign; Moses did not. Moses’ sign belongs in the same class as other signs about the future (1Sa 2:34; 10:2, 3, 5; 2Ki 19:29, et al.). Thus while God gave “signs” as “proofs” to the people (Ex 4:1–9), interestingly enough he gave no such “signs” to Moses himself but asked him to believe and trust in his word and promised to be present (cf. Mt 28:20). There was also more than a hint in this sign that the mission of Moses went beyond a mere deliverance of a nation from bondage; Israel was to be set free to “worship” God.

b. What if they ask what your name is? (3:13–22)

13 Moses did not anticipate being asked, “By what name is this deity called?” Rather, he feared that if he announced that the God of their fathers, the patriarchs, had sent him to them, the people would bluntly ask him, “What is his name?” The Hebrew seeks the significance, character, quality, and interpretation of the name. Therefore, what they needed to know was “What does that name mean or signify in circumstances such as we are in?”

14–15 God gave two answers to the problem posed by Moses. The second answer builds on the basic explanation of the meaning of the Lord’s name and links that name with previous and all future generations.

Perhaps the most natural explanation that does fullest justice to the meaning of “I AM” is that this name is connected with some form of the verb “to be” and is to be seen as expressing the nature, character, and essence of the promise in v.12: “I will be with you.” What, then, was his name? The answer was that “[my name in its inner significance is] I am, for I am/will be [present].” While it may sound to Western ears that God was deliberately trying to avoid disclosing his name, the context shows that he was actually doing the opposite. Often this construction is used to express a totality, intensity, or emphasis. Therefore, the formula means “I am truly he who exists and who will be dynamically present then and there in the situation to which I am sending you.”

This was no new God to Israel; it was the same God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob who was sending Moses. His name was Yahweh (= LORD; GK 3378). For the first time God used the standard third-person form of the verb “to be” with the famous four consonants YHWH. This was to be his “name” (GK 9005) forever. His “name” was his person, his character, his authority, his power, and his reputation. So linked was the person of the Lord and his name that both were often used interchangeably (e.g., Dt 28:58; Ps 18:49). This name was to be a “memorial”; it was to be for the act of uttering the mighty deeds of God throughout all generations.

16–18a The “elders of Israel” were the heads of various families (6:14–15, 25; 12:21; Nu 2) or tribes. Moses was to deliver God’s message to this body of men and to get them to accompany him when he went to Pharaoh. The message came in the name of “the LORD,” who was the same as the God of the patriarchs. It began with a repetition of the words used by Joseph on his deathbed: lit., “I have surely visited you” (NIV, “I have watched over you”), and “I have promised to bring you up out of your misery in Egypt.” Joseph had prophesied the very deliverance announced by Moses (see Ge 50:24). Thus the repetition here was equivalent to saying that the Lord would complete and fulfill what he had begun to do as spoken by Joseph. In fact, the very word used for misery in v.17 was used in the original promise to Abraham in Ge 15:13 that the Egyptians would “mistreat” them for four hundred years. Moses was assured of a sympathetic hearing from the elders, for the hearts of human beings are in the hands of God.

18b–20 Moses and the elders were instructed first to make only a moderate and limited request of Pharaoh for a temporary leave to offer sacrifices to the Lord their God. This was not an example of a half-truth or a ruse and an attempt to deceive Pharaoh. God deliberately graded his requests of Pharaoh from easier (a three-day journey with an understood obligation to return) to more difficult (the total release of the enslaved people) in order to give him every possible aid in making an admittedly difficult political and economic decision. God certainly knew this king of Egypt well enough to know what his reactions would be. Therefore Moses was cautioned not to misconstrue any rejection he received as a sign that God had not called him or that God was not with him—all to no avail; for Moses later raised those very complaints (5:22–23).

21–22 God had promised Abram that after Israel had served for four hundred years, they would “come out with great possessions” (Ge 15:14). Thus the early chapters of Exodus systematically record the fulfillment of one patriarchal promise after another to make the connection clear. The taking of spoils from the Egyptians was to be explained by a simple request and by granting divine favor to the Israelites’ request. The Israelites themselves were to live by this same principle of providing a present to a slave who was to be released every seven years (Dt 15:13). Charges of fraud, deception, deceit, and villainy against Israel are all misplaced. The fact is that the ignominy of their slavery is reversed in this sign of the recovery of their personhood—why even the children were to be decked in the jewels and the gifts of clothing!

c. What if they will not believe me? (4:1–9)

1 Moses did not flatly contradict God’s assurance in 3:17. Both the Hebrew and the LXX make his question a hypothetical situation. But it does indicate that Moses was by no means a shining model of faith and trust in God. At the same time, neither could Moses have been certain as to the response of his fellow Israelites in Egypt. Moses stalled for time by posing further nuances to what he had already been told.

2–5 The first sign. God’s prophets were accredited by “signs and wonders” (cf. Dt 13:1–3) with the sole purpose of validating the messenger and the message—that both were truly from God. Accordingly, Moses was given a “sign” (see comment on 3:12) to perform “so that they may believe that the LORD . . . has appeared to you.”

The staff in Moses’ hand was ordinary and unspectacular, but when it was thrown on the ground, as God commanded, it became a snake. It is perhaps too much to connect this snake directly with the uraeus (or cobra) worn on the headdress of Pharaoh (as if Moses had Egypt’s king by the tail). In order to underscore its supernatural nature, Moses was instructed to grasp the serpent by its tail to further prove the divine source of this miracle; for one would normally pick up a serpent by the neck.

6–7 The second sign. The Hebrew word for leprosy covered a number of assorted diseases. Actually, leprosy, or Hansen’s disease, was known in antiquity. But leprosy in the Bible apparently also covered cases of psoriasis, vitiligo, ringworm, syphilis, mildew, and the rot—all affecting garments and houses as well as people in some cases. Which was involved here is uncertain, but the condition of the skin was such that its color resembled snow. Any small or ordinary skin annoyance would hardly be of any “sign” value. It had to pose a greater threat to the life and health of Moses if the instantaneous cure was also to reflect the greatness and majesty of God’s power. The significance of this power to take away the health of the body and then to restore it again so that the affected part was “like the rest of his flesh” was to warn Pharaoh that this God, who had sent Moses, had the power to inflict or to save whatever he wanted with just a word or a gesture from his ambassador.

8–9 The third sign. The Lord next seized the initiative by using almost identical terms to those used by Moses in v.1. What was not being heeded in each case was literally “the voice” of these two signs. But their “voices” would leave Israel just as accountable as the “voice” of the words of Moses (v.1). Israel was to be confronted by God through the “voice” of his word and the “voice” of his miracles. This indicates that an appropriate significance would attach itself to each sign.

In this third sign Moses was to take some water from the river (the first plague would later be performed in the Nile) and turn it into blood. The Nile, which flowed with the blood of innocent Hebrew victims, would itself witness to its involuntary carnage with this miracle. Would the point of the “sign” be wasted on any Hebrew—or Egyptian? Like Abel’s blood that cried out from the ground, so would the infants’ whose lives had been demanded by Pharaoh (1:22). Egypt’s mighty god, the Nile, was dominated by the Lord God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

d. What about my slow tongue? (4:10–12)

10 Moses began with yet another objection: “I have never been eloquent” (lit., “a man of words”). Then in a truly Oriental phrase, he added, literally, “not since yesterday and not since the third day,” which adds up to simply “never before.” Not even the experience at the bush had remedied this problem. Moses summed it all up: he was “slow of speech and tongue.” Scarcely could this imply that he had a natural speech impediment or that he was a stammerer (cf. Ac 7:22). Thus Moses’ complaint was not in a defective articulation but in his inability to take command of Hebrew and Egyptian with a ready and copious supply of words and thoughts to beat back all objections from his brothers and Pharaoh—though he does quite well with God!

11–12 God answered Moses with a question that takes on proverbial status (Ps 94:9). The gifts of speech, sight, and hearing are from the same Lord who was sending this hesitant leader. While God was not to be blamed for directly creating any defects, his wise providence in allowing these deprivations as well as his goodness in bestowing their ordinary functions mirror his ability to meet any emergency Moses might have suggested. So God announced, “I will help you speak” (lit., “I will be with your mouth”) “and will teach you what to say.”

e. Why can you not find someone else? (4:13–17)

13–14a Moses’ groundless opposition angered God. Moses could think of no more good objections, for God had met every one point by point. So God’s unwilling servant revealed the true nature of his heart: literally he said, “Send, I beg you, by the hand [of whom] you will send,” which is a delightful Hebraism for “choose any other man, not me!” (NIV, “please send someone else”).

14b–17 Nevertheless, God mercifully decided still to use his reluctant servant by sending his brother, Aaron, to supply any deficiency Moses might have felt. However, Moses had a price to pay for his intransigence: Aaron would receive the honor of leading the priesthood, which appears to be the reason for including this reference to “the Levite” (cf. 1Ch 23:13). Once more the omniscience of God is seen in that Aaron was “already on his way to meet [Moses],” having begun at the special prompting of God (v.27). Whether Aaron came with the news that the king who sought Moses’ life was dead (2:15) or for some other reason is not known.

The arrangement was that Moses was literally “to become God” to Aaron, and Aaron was to become Moses’ mouth (or “prophet,” according to 7:1). Nothing defines more accurately the intimate relationship between God and his prophet than 4:16 and 7:1. There were to be no more excuses or discussions: “You shall speak to him and put words in his mouth.” Further, God would teach both of them what they were to do. As for action and deeds, it would be the very humble staff in Moses’ hand that God would use to perform the miracles he already had begun to speak about (3:20) and to show to Moses (4:2–8).

6. Preparing a leader’s family (4:18–26)

18 Moses left the region of Sinai and went to Midian to ask Jethro’s permission to return to Egypt. Even the call of God did not erase the need for human courtesy and respect. Interestingly, Moses did not share the real reason for his desire to return to Egypt. The reason he gave was “to see if any of [my own people] are still alive.” So Jethro granted Moses permission to go and wished him well.

19–20 This short section informs us that Moses’ conversion took place in Midian, not in Sinai where God had appeared to him, and that Moses had made his decision to return before he heard that the Pharaoh who had sought his life had already died. The news of the passing of his enemies may have influenced him to decide to take along his wife, Zipporah, and their two sons. Up till now only one son, Gershom, has been mentioned (2:22). Eliezer, though unmentioned in this text, probably had been born (18:4); thus the plural is correct here. Moses’ family is not mentioned again until Jethro’s visit with Moses and the Israelites camped at Sinai (ch. 18).

Moses took along the “staff of God.” What had once been ordinary became extraordinary by virtue of its use in the service of God. So equipped, Moses prepared to return to Egypt.

21–23 By way of summary, the Lord rehearsed the key features of his previous directives to Moses: (1) you will perform miracles before Pharaoh; (2) Pharaoh will harden his heart and not release the people; (3) you are to inform him that since Israel is “my firstborn son,” the Israelites must be set free so that they might worship me; and (4) Pharaoh’s refusal will lead to the death of his firstborn son.

The expression “I will harden [Pharaoh’s] heart so that he will not let the people go” is used here for the first time. In all, there are ten places where “hardening” (GK 2616 & 3877) of Pharaoh is ascribed to God (4:21; 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17). But it must be stated just as firmly that Pharaoh hardened his own heart in another ten passages (7:13, 14, 22; 8:15, 19, 32; 9:7, 34, 35; 13:15). Thus the hardening was as much Pharaoh’s own act as it was the work of God. Even more significant is the fact that Pharaoh alone was the agent of the hardening in the first sign and in all the first five plagues. Not until the sixth plague was it stated that God actually moved in and hardened Pharaoh’s heart (9:12), as he had warned Moses in Midian that he would have to do.

The announcement that Israel was God’s “son” (GK 1201), yes, even his “firstborn” (GK 1147), may have stunned Pharaoh; for he was accustomed to regarding himself alone as the “son of the gods.” But for a whole people to be a “son” of the deity was a little surprising. Added to this filial relationship was the declaration that Israel was God’s “firstborn,” which does not mean “first” in chronological order, because Jacob (renamed Israel) was actually born after his twin, Esau. Here God meant “first in rank,” firstborn by way of preeminence, with all the rights, privileges, and responsibilities of a “firstborn.” Thus what had previously rested on natural rights of primogeniture now rested on grace. With it went the privilege given by God to the seed of Abraham, namely, that by means of this “firstborn” all the nations of the earth would be blessed. The penalty that Pharaoh would ultimately pay for his refusal to acknowledge Israel as the Lord’s son and firstborn, however, would be aimed at his own firstborn. Just as 3:12 had included an adumbration of Moses’ return to Sinai, so vv.21–23 intend to show the future work of God, beginning with the “wonders” of the plagues and ending climactically with a threat to Pharaoh’s firstborn.

24–26 This paragraph has continued to baffle interpreters. The place to begin to solve these problems is with the explanation given in the text itself. Verse 26b explains that this whole episode—what Zipporah did, what she said, and on whom she operated—all have reference to the rite of circumcision. The link with the context must revolve around Pharaoh’s “son,” his “firstborn” (v.23), and Moses’ “son,” perhaps also his “firstborn,” along with the fact that all Israel was God’s son, his firstborn. The Lord had attacked Moses as he was en route to accomplish the mission of God in Egypt. The nature of this nearly fatal experience is not known. That Moses was the object of the divine action is clear from the fact that the otherwise unspecified son would need to be identified as belonging to someone other than Moses. The sudden introduction of Zipporah’s action leads us to believe that she instinctively connected her husband’s peril (a malady so great that it left only her hands free to act) with their failure to circumcise their son. This she immediately proceeded to do. But her words of reproach indicate that the root of the problem of not circumcising the boy earlier lay in her revulsion and disgust with this rite.

The narrative was included at this point to demonstrate that an additional factor was needed in the preparation of God’s commissioned servant: the preparation of his family. In Ge 17:10–14 God had commanded Abraham to circumcise every male on the eighth day as a sign of the covenant; any uncircumcised male was to be cut off from his people. However, in this case the father was suffering for his refusal to circumcise his son. Thus for one small neglect, apparently out of deference to his wife’s wishes, or perhaps to keep peace in the home, Moses almost forfeited his opportunity to serve God and wasted eighty years of preparation and training! To further underscore this connection between Moses’ grave condition and the circumcision of his son, Zipporah took the excised prepuce and touched Moses’ feet. The Lord let Moses go, and the grip of death was lifted.

C. First Steps in Leadership (4:27–7:5)

1. Reinforced by a brother (4:27–31)

27–28 At God’s command Aaron, now eighty-three years of age, was to meet Moses midway en route to Egypt at the “mountain of God” (i.e., Horeb; see 3:1). As predicted in v.14, Aaron “kissed” Moses. The men had much to share as to what had happened during the forty years they were apart, but Moses’ words about God’s liberating directives and miraculous signs were most prominent.

29–31 Immediately the narrative jumps ahead to the meeting with the elders that Moses had been instructed to convene when he arrived in Egypt. Evidently God wished to see duly constituted authority respected; therefore an appeal needed to be made to Israel’s existing leadership and their consent obtained before initiating any requests of Pharaoh. Aaron acted as chief spokesman in relaying all that God had said to Moses. In addition, though Moses alone had been told (v.17) to perform the signs God had given in vv.1–9, both Moses and Aaron performed the miracles.

Since the elders represented the people and subsequently reported to them what they had heard and seen from Moses and Aaron, the text quickly compresses each of these steps in v.30 by saying all this was done “before” (lit., “in the sight of”) the people. The response was just as had been predicted in 3:18—“they believed.” The pressure of physical hardship had made this people more receptive than would be their custom in later years. Whether the signs were needed, as Moses had feared in v.1, the text has no comment. Especially heartening was the fact that God cared about them and their misery. Their response was immediately to worship the Lord, for he was the One who had “visited” (NIV, “was concerned about”) them and “had seen” their trouble.

2. Rebuffed by the enemy (5:1–14)

1–2 Some time later Moses and Aaron, perhaps accompanied by the elders (cf. 3:18), went to Pharaoh and boldly demanded that he release the people. They wished to celebrate a festival to this God in whose name the demand was being made, namely, “the LORD, the God of Israel” (see comment on 3:14–15). Pharaoh’s retort to this affront to his sole right to command these slaves was crisp and cynical. Indeed, if God chose to identify himself with such a hapless and hopeless lot of slaves, and if he was so powerless to effect their deliverance, why should Pharaoh fear him or obey his voice? Pharaoh’s answer was clear: “No!”

3 Perhaps stunned by Pharaoh’s insolence and arrogance, Moses and Aaron recast their request in milder terms. Acting now as representatives of the people and in language given at the burning bush, the demand is changed to a humble request. God’s servants warned Pharaoh that should he disallow this temporary release, he could suffer untold losses; for this God might allow all sorts of pestilence to break out, or he might even send an invader across the eastern frontier where Israel lived in vulnerable exposure.

4–14 Pharaoh was unmoved by any of these requests or threats. In his judgment the people were much too lazy or too idle, and Moses and Aaron were disturbers of the peace at best and plotters of sedition against the throne at worst. His question to them was in essence, “Why are you encouraging this?” There were already too many people (another witness to God’s covenantal faithfulness), and should he give them rest from their labors to further increase their numbers?

The Egyptian slave drivers were to instruct the Israelite “foremen” that straw would no longer be provided for the bricks Israel had to produce. From then on Israel was to rummage the countryside for what stubble and straw they could find without decreasing their daily quota of bricks. Chopped straw was mixed in with the clay to make the bricks more pliable and stronger. So the people were scattered all over Egypt while the slave drivers kept beating the Israelite foremen and pressuring them to meet their daily quota of bricks.

3. Rebuffed by the enslaved (5:15–21)

15–16 The Hebrew foremen, unaware of the total deterioration of their position due to Moses and Aaron’s request of Pharaoh, personally appealed the “No straw policy.” In a courteous but bitter complaint, they asked, “Why have you treated your servants this way? We are given no straw; we are constantly pressed to keep making bricks; we are beaten—and the fault, sir, lies with your own people.” This last charge seems to deferentially use the words “your people” in a circumlocution for Pharaoh himself.

17–18 Pharaoh’s analysis of the situation has been reduced to a single word: “lazy.” He repeated the word for emphasis (cf. v.8). If their request was “Let us go . . . now,” then he was ready to render his conclusion: “Get to work.” No straw would be supplied, and no falling behind in quotas would be allowed either.

19–21 Only now did the real untenability of their position begin to come home to the foremen. Moses and Aaron had deliberately “stationed” (NIV, “waiting”) themselves so as apparently to be the first to debrief the men as they emerged from their meeting with Pharaoh; for they had had a fairly good idea of what would be the outcome of the foremen’s audience with the king of Egypt. What they may not have expected was the full venting of the foremen’s anger when they “found” them.

Instead of earning respect from these Hebrew foremen for all their efforts to alleviate their brutal condition, Moses and Aaron felt, in no uncertain terms, the heat of the foremen’s anger. They asked God to judge these two troublemakers, for they were making Israel’s reputation to stink. The words of vv.20–21 reflect those of v.3. Instead of a plague “striking” Israel and a “sword” coming, Moses and Aaron, not an enemy, had put a sword in Pharaoh’s hands. So it happened that they “struck,” or as we would say, “happened to bump into,” Moses and Aaron.

4. Revisited by old objections (5:22–23)

22–23 Even though Moses had been forewarned from the start that Pharaoh would not accede to God’s requests, he was not prepared for the effect this refusal would have on his own fellow Israelites. Filled with an “I told you so” attitude, it was Moses’ turn to ask “Why?” (cf. Pharaoh in v.4, the foremen in v.15): “Why did you ever send me [in the first place]?” (lit. tr.). Fortunately, Moses did not vent his wrath on the foremen, but he did pour out to God the keenness of his resentment. Moses did not charge God directly with authoring this evil, for the idiom only means that God allowed and permitted such trouble as Pharaoh had thus spawned.

The clincher for Moses was v.23. His prayer (in essence) was, “O Lord, why is all this happening? Why did you ever send me?” Then he concluded: “Besides, you haven’t done what you said you would anyway—deliver them! I’ve done nothing but bring/make trouble since I arrived here!” Obviously, Moses was again wrestling with some of his old objections (cf. 3:11–4:17). In his estimation things were moving too slowly, and the suffering was intensifying rather than letting up.

5. Reinforced by the Name of God (6:1–8)

1 There were no direct answers to Moses’ questions, for these were to be gathered from his experience as their leader. But Moses’ complaint about the time could now be answered, for God announced his “now”—he would delay no longer. The promised show of God’s power would commence immediately with a show of his “mighty hand” (cf. 3:19).

2–5 The heart of God’s response to Moses and the people was a fresh revelation of God’s character and nature. One phrase stands out: “I am the LORD,” which appears four times from v.2 to v.8. Once again God reminded Moses that he was the God who had promised the land of Canaan to the patriarchs and that he had also seen the affliction of his chosen people. Moreover, whereas in the past the patriarchs had known him in the character of and in his capacity as El Shaddai (“God Almighty”; cf. Ge 17:1; 28:3; et al.)—the name that disclosed his power to impart life, to increase the goods of life, and to deal with all unrighteousness—now he would be known as “the LORD” (i.e., Yahweh; GK 3378).

Moses and Israel (and even the Egyptians later) would shortly know what “I am the LORD” meant. This would not be the first instance of the use of that name, for it had already occurred some 162 times in Genesis. Significantly, people “began to call on the name of the LORD” as early as Ge 4:26. The Lord is the God who would personally, dynamically, and faithfully be present to fulfill the covenant he had made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The patriarchs had only the promises, not the things promised. The fullness of time had come when God was to be known in the capacity and character of his name Yahweh, as he fulfilled what he had promised and did what he had decreed. These deeds are further enumerated and spelled out in the seven promises of vv.6–8.

6–8 The contents of God’s ancient promises are brought together and arranged so as to explain what “I am the LORD” means.

1. There were three first-person verbs with God’s promise of redemption (v.6): (1) “I will bring you out”; (2) “I will free you”; (3) “I will redeem you.” God promises to “redeem” Israel with the same “mighty acts of judgment” he had alluded to in 3:20 and 4:23 and had predicted long ago to Abraham in Ge 15:14. The plagues were to be judgments for crimes as well as spectacular wonders to instill faith.

2. Two more first-person verbs detailed God’s promise to adopt Israel as his own people (v.7): (1) “I will take you as my own people”; (2) “I will be your God.” These two promises will serve as two parts of the tripartite formula to be repeated in the Old and New Testaments almost fifty times: “I will be your God, you shall be my people and I will dwell in the midst of you” (cf. Ge 17:7–8; 28:21; Ex 29:45–46; et al.).

3. The last two promises focused on God’s promise of the land (v.8): (1) “I will bring you to the land”; (2) “I will give it to you.” This he pledged with the oath of his uplifted hand (cf. Ge 22:16; 26:3) so that by two immutable things—his word of promise and his oath—Israel (and all subsequent believers; cf. Heb 6:17–18) might have a strong encouragement and a solid confidence in the future. Then, as if to remind Israel once again, God concluded with his signature: “I am the LORD.”

6. Reminders of Moses’ lowly origins (6:9–7:5)

9–12 In spite of the grandeur of what “I am the LORD” meant for Israel, the people did not listen “for shortness of breath” (NIV, “their discouragement”). It was the inward pressure caused by deep anguish that prevented proper breathing—like children sobbing and gasping for their breath. This made such an impact on Moses that he had another attack of self-distrust and despondency. How could he persuade Pharaoh when he failed so miserably to impress his own countrymen who presumably would have had a naturally deep interest in what he had to say, given their circumstances. Anyway, his lips were “faltering” (cf. NIV note, “uncircumcised”) in the job they had been given to do. Thus Moses returned to his fourth objection (4:10).

13–30 The stage has been set in 1:1–6:12 for the main action to begin. However, before that happens, it is important to know just who were “Aaron and Moses to whom the LORD” had spoken. In fact, the whole genealogy of vv.14–25 is surrounded and framed by the near verbatim repetition of vv.10–13 in vv.26–30 and v.14a in v.25b. Therefore, the genealogical list concentrates on two men and how it was that they happened to be at this precise and momentous juncture in the history of humans and nations.

Everything in the list suggests that God’s choosing of Moses had nothing to do with natural advantage or ability. The list stops after naming only three of Jacob’s sons—Reuben, Simeon, and Levi—for its object had been reached. Moses and Aaron sprang, not from the “firstborn,” Reuben, but from Levi, Jacob’s third son, and not even then from Levi’s oldest son but Kohath, his second son. And Moses was not even the oldest son of his father, for Aaron was older. Moses’ calling and election of God were a gift of grace and not based on rights and privileges of birth.

So wicked were Jacob’s three older sons that they each inherited a curse: Reuben lost his birthright as “firstborn” (Ge 49:3–4), and Simeon and Levi were denied an inheritance with the tribes and were scattered instead (vv.5–8). But while Reuben’s and Simeon’s descendants did morally follow in their fathers’ footsteps, Levi’s descendants, with devotion to God, turned what was a curse into a blessing and used their dispersion through the tribes as an avenue of blessing to all through the priesthood and service at the sanctuary of God. This honor, however, did not prevent Levi’s descendant Korah (vv.21–24) from destroying himself by his own rebellion (Nu 16); yet his descendants were not thereby forever adversely determined for evil, for they later rose to a place of high position in the temple and in composing Pss 42–49, 84–85, and 87. So the making of “this same Moses and Aaron,” as well as the uses they were put to after they were made, were totally the work of God. Nevertheless, the record also made plain that there was a congruity between the experiences and all the endowments that had accrued to Moses during these eighty years of life; thus election worked in the natural realm as well as the spiritual.

The text returns to repeat the words of vv.10–13 in vv.26–30, as if to say, “Look who is talking back to God! A man of few credentials except those given him in the providence and grace of God!” But never mind that, v.28 seems to affirm; it is now a whole new game. The hour had come, and the name of the LORD would be all the equipment Moses would need.

7:1–5 While the LORD had made Moses as “God” to Aaron and Aaron in turn as his “prophet” (GK 5566) to the people, Moses was also ordained as “God” to Pharaoh in that he would speak and act with authority and power from above and Aaron would be Moses’ “prophet” addressing Pharaoh (cf. 4:15–16). But again this team was warned that Pharaoh’s heart would be “hardened” (see comment on 4:21), even though God would graciously provide him with supporting evidence by way of signs and wonders. Nevertheless, after God had judged Egypt with his “mighty acts of judgment,” Israel would come out by its “divisions.”

Not only would Israel know what was meant by the name “LORD,” but so would the Egyptians. In addition to understanding the significance of that name (Heb. YHWH or Yahweh), these miracles would also be an invitation for the Egyptians to personally believe in Israel’s Lord. Thus the invitation was pressed repeatedly in 7:5; 8:10, 22; 9:14, 16, 29; 14:4, 18—and some apparently did believe, for there was “a mixed multitude” (12:38 KJV) that left Egypt with Israel.

D. Judgment and Salvation Through the Plagues (7:6–11:10)

1. Presenting the signs of divine authority (7:6–13)

6–9 After eighty years of preparation, Moses began his life work. He and Aaron were directed to reappear before Pharaoh, who in turn would request them to perform a miracle, presumably to assure him that they were messengers of Israel’s God.

Significantly, Scripture judges Pharaoh’s demand for validation of such claims as reasonable. The Lord informed Moses to use the first of the three signs he had drawn on to convince Israel that he was indeed an accredited messenger of God (see 4:2–9, 30–31). However, in this instance Aaron’s staff (it was the same as Moses’ staff or the staff of God; cf. 4:17; 7:15, 17, 19–20), when cast down, became a tannin (GK 9490; “great serpent,” “dragon,” or “crocodile”; in 4:3–4 it became a nahash, “snake”; GK 5729). The connection of the name tannin with the symbol of Egypt is clear from Ps 74:13 and Eze 29:3.

10–13 Moses and Aaron did exactly as God instructed them—only to learn that Pharaoh’s wise men, sorcerers, and magicians were able to imitate the same feat by their magical arts. The use of magic in Egypt is well-documented in the Westcar Papyrus, where magicians are credited with changing wax crocodiles into real ones only to be turned back to wax again after seizing their tails.

The relation between Aaron’s miracle and the magical act of the magicians, whom Paul knew by the names of Jannes and Jambres in 2Ti 3:8, is hard to define. Possibly by the use of illusion and deceptive appearances they were able to cast spells over what appeared to be their staffs but which actually were serpents rendered immobile (catalepsy) by pressure on the nape of their necks and by the use of magical spells. Or perhaps it was by demonic power. However, as evidence of God’s greater power, Pharaoh’s magicians lost their “staffs” when Aaron’s “swallowed [them] up.” But Pharaoh was unaffected. His heart “became hard.”

2. First plague: water turned to blood (7:14–24)

14–18 Moses was instructed by God to go early (so in 8:20) in the morning with his brother, Aaron, to intercept Pharaoh and his officials as they went out to the Nile (cf. v.20). Pharaoh’s purpose for going here remains unknown, perhaps to worship the Nile River god, Hapi. Moses and Aaron, however, were there to remind Pharaoh that “the LORD, the God of the Hebrews” had sent them (5:1); yet the king of Egypt remained resolute in his defiance of this Lord. Therefore God would help Pharaoh “know” who he was (cf. 5:2). God would change the water of the Nile River into blood when Moses struck the Nile with his staff.

19–21 When Aaron stretched out his staff and struck what the Egyptians regarded as sacred, the Nile and the water all over Egypt turned to blood. What was the “blood” (GK 1947)? Some scholars suggest that since all the plagues followed a natural cycle and all happened in one year, this first plague could be connected with an unusually high Nile flood in July and August. The sources for the Nile’s inundation are the equatorial rains that fill the White Nile, which originates in east-central Africa (present-day Uganda) and flows sluggishly through swamps in eastern Sudan, and the Blue Nile and the Atbara River, which both fill with melting snow from the mountains and become raging torrents filled with tons of red soil from the basins of both these rivers. The higher the inundation, the deeper the color of the red waters. In addition to this discoloration, a type of algae, known as flagellates, comes from the Sudan swamps and Lake Tana along the White Nile, which produces the stench and the deadly fluctuation in the oxygen level of the river that proves to be so fatal to the fish. Such a process, at the command of God, seems to be the case for this first plague rather than any chemical change of the water into red and white corpuscles (cf. Joel 2:31: “the moon [will be changed] to blood”; or 2Ki 3:22, where, however, the water looked “like blood”). Unlike other plagues and in agreement with this natural phenomenon, this plague did not stop suddenly. This change affected the “streams” (= seven [in Herodotus] branches of the Nile), the canals (to fertilize the fields), the ponds (left from the overflowing Nile), and the reservoirs (artificially made to store water for later use).

22–24 Once again Pharaoh’s magicians applied their “secret arts” and imitated the miracle sufficiently to blunt the force of it on Pharaoh’s conscience. The question where they found any unblemished water if the fourfold water system in “all Egypt” (vv.19, 21) was affected, is answered in v.24—from subterranean water from freshly dug wells. But Pharaoh remained unmoved and merely returned to his palace from the bloody river’s edge: his heart grew rigid and hard in spite of this evidence.

3. Second plague: frogs (7:25–8:15)

25–8:5 Seven days after the first plague had begun, Moses and Aaron were instructed by God to take their demands to the king’s palace. If he refused to grant their repeated request to go to the desert to worship the Lord, they were to announce in the set formula, “I will plague your whole country with frogs.” This was not to be a “sign” but a “plague” only. In comparison with what was to come, this was only a trivial annoyance.

6–7 On Aaron’s signal the frogs emerged from the water and “covered” the land. These pesky creatures, though regarded as sacred to the Egyptians, were God’s scourge to whip the Egyptians into facing the living God. The intensification of the nuisance by Pharaoh’s magicians was totally ignored by him. The fact was that tons of croaking, crawling, creeping intruders were everywhere.

8–15 Why should the frogs so suddenly abandon their natural habitat in August during a high Nile and invade the homes, bedrooms, ovens, kneading troughs, and even the palace itself? And why should they likewise die off so suddenly? Perhaps the frogs abandoned all the polluted and overflowing waterways (cf. 7:19) and sought cover from the sun on dry land in homes where possibly the presence of some unadulterated water attracted them. However, since they had already been exposed to spores of bacillus anthracis from the death spread along the waterways, the frogs also suddenly collapsed and died.

Pharaoh had finally been forced to acknowledge the power of the Lord, not by human armies, but by squadrons of loathsome little frogs. Now he knew who this “LORD” was (cf. 5:2), and he acceded to Moses and Aaron’s request—only to renege later on.

Moses’ response to Pharaoh’s desperate or, as some think, cynical plea was to dare Pharaoh to test his prophetic credentials and, more important, the power of God by setting the time when he wished to be rid of this plague. Pharaoh’s quick response of “tomorrow” led Moses to enter into some intensely earnest prayer. Moses’ freedom to negotiate on his own terms and then, as it were, to have God back him up is remarkable. The frogs dropped dead all over the place—in the houses, fields, and open courtyards. Frogs were piled up in heaps, and there was a firm reminder to aid Pharaoh’s wavering memory—the stench of dead frogs. Nevertheless, that faded and so did Pharaoh’s permission. This “relief” was worse than the plague for this proud king. People do not often learn the righteousness of God when he grants them his mercy and his favor (Ps 78:34–42; Isa 26:10).

4. Third plague: gnats (8:16–19)

16–17 The third plague began without warning to Pharaoh or his magicians. God again used the outstretched staff in the hand of Aaron to initiate this plague. Aaron struck the dust of the ground, just as he had struck the Nile in the first plague (7:20), and “all the dust throughout the land of Egypt became gnats.” The word “gnats” occurs five times in this passage and nowhere else except in the parallel passage of Ps 105:31. It is debatable whether this word means “lice” (so KJV et al.) or “gnats” or “mosquitoes,” as we favor (with most interpreters).

18–19 On their fourth attempt to duplicate the miracles of Moses and Aaron, the Egyptian magicians admitted defeat. In spite of what success they did or did not experience in the previous three encounters (and it could well have been through sleight of hand—given the advance notice of the nature of the plague or sign in those cases—or perhaps it was just plain demonic, supernatural empowerment to mimic God’s power), they now realized that the plague of the gnats was the “finger of God,” i.e., the result of his power. But Pharaoh was not so persuaded in his heart and mind—he remained adamant and opposed to any Israelite demands.

5. Fourth plague: flies (8:20–32)

20–21 As in the first plague, Moses was sent to intercept Pharaoh again as he went down to the Nile early in the morning. This time Pharaoh and all his people and their houses were threatened with a plague of “flies.” It seems best to say that the fly Stomoxys calcitrans best fulfills all the conditions of the text. This fly multiplies rapidly in tropical or subtropical regions (hence the delta with its Mediterranean climate would be exempt) in the fall by laying its six hundred to eight hundred eggs in dung or rotting plant debris. When it is full grown, the fly prefers to infest houses and stables, and it bites both humans and animals, usually in the lower extremities. Thus it becomes the principal transmitter of skin anthrax (see plague six), which it contracts by crawling over the carcasses of animals that have died of internal anthrax.

22–24 By inaugurating a “distinction” (GK 7151) between Moses’ people and Pharaoh’s people, God intended to aid those hardened Egyptian hearts who suspected that nothing more than chance or difficult times had been involved in the preceding three plagues. This distinction is found in the fourth, fifth, seventh, ninth, and tenth plagues. The purpose of this preferential treatment to Israel was to teach Pharaoh and the Egyptians that the Lord God of Israel was in the midst of this land doing these works; it was not one of their local deities. Gods were thought by ancient Near Easterners to possess no power except on their own home ground. But not so here! The innocent were being delivered and the guilty afflicted because this God was in their midst. He would again do a “miraculous sign” designed to evoke faith in him from the Egyptians and the release of Israel.

In another innovative feature Moses announced in advance when the plague was due to strike, giving the Egyptians time to repent. This advance notice is found in the fourth, fifth, sixth, eighth, and tenth plagues. Moreover, Pharaoh and his court were again singled out as the first victims of this plague because of the heavy responsibility they bore for their intransigence.

25–32 Moses’ claim—that if Israel sacrificed animals in Egypt, it would be extremely offensive to the Egyptians—has been challenged by some commentators as a clever ruse on Moses’ part. Thus Moses rejected Pharaoh’s counteroffer to allow Israel to sacrifice in Egypt. Finally Pharaoh conceded the long-denied permission. With a note of self-importance he pontificated, “I will let you go . . . but you must not go very far.” And as if to show what his real thoughts were all along, he quickly added, “Now pray for me.”

Moses was not to be put down, for his mission likewise had dignity; so he too began with the pronoun “I”: “I am leaving you, and I will pray” (lit. tr.). Moses, with an obvious rebuke, said in effect, “Don’t you ‘however’ me when you are in such a poor bargaining position.” But then on a courteous note, with a switch to the third-person form of address, he continued, “Only be sure that Pharaoh does not act deceitfully again.”

The plague was removed through Moses’ prayer (cf. 1Ki 18:42; Am 7:2, 5). So effective was the power of prayer and the evidence that God was in their midst that “not a fly remained.” But Pharaoh once again (cf. second plague, 8:15) returned to his hard-nosed stand once he obtained the physical relief he desired.

6. Fifth plague: cattle murrain (9:1–7)

1–4 The fifth plague was patterned after the second: Moses was to go to Pharaoh’s palace and announce the next pestilence. A “terrible plague” would be brought, not by God’s “finger,” as the Egyptian magicians had put it in 8:19, but by his “hand.” It would fall on all the cattle in the field. There is no need to press the expression “all the livestock” to mean each and every one and then find there are no Egyptian cattle left for the seventh plague (vv.19, 25), for it is already plain in v.3 that the plague affected only those cattle “in the field.” Normally the Egyptian cattle were stabled from May through December, during the flood and the drying-off periods when the pastures were waterlogged. Thus some of the cattle were already being turned out to pasture down south; so it must have been sometime in the month of January. These cattle were then affected when they came into contact with the heaps of dead frogs left from the second plague and died of bacillus anthracis, the hoof and mouth disease.

The Israelite cattle were exempted from the plague, possibly because the delta would have been slower in recovering from the effects of the flood, which was farther downstream. Also, the Israelites’ different attitude toward corpses—they took precautions to deal with the heaps of dead carcasses—may have spared their own cattle. This was the second plague where God placed a distinction between the Egyptians and the Israelites.

5–7 The interval between the announcement and the morrow, when the fifth plague was to take effect, was to allow time for a believing response from Pharaoh and the Egyptians. Presumably some believed and attempted to rescue their animals by bringing them in from the fields. Others purposely delayed turning their cattle out to pasture.

When Pharaoh heard that all the Israelite cattle had miraculously escaped the cattle plague, he sent envoys to Goshen to investigate. The rumor was true. Pharaoh must have had his own explanations and rationalizations, for his position and heart again became resolute and unyielding. Meanwhile, another part of Egypt’s wide array of gods was hard hit: the Apis, or sacred bull Ptah; the calf god Ra; the cows of Hathor; the jackal-headed god Anubis; and the bull Bakis of the god Mentu. The evidence was too strong to be mere coincidence: (1) the time was set by the Lord, the God of the Hebrews; (2) a “distinction” was made between the cattle of the two peoples; and (3) the results were total: all Egyptian cattle “in the field” died; not one head of Israelite livestock perished.

7. Sixth plague: boils (9:8–12)

8–9 Like the third plague, this one was sent unannounced. For the first time human lives are attacked and endangered, and thus it was a foreshadowing of the tenth and most dreadful of all the plagues. With a touch of divine irony and poetic justice, Moses and Aaron were each to take two handfuls (the form is dual) of soot from a limekiln or brick-making furnace, the symbol of Israel’s bondage (see 1:14; 5:7–19). The soot must have been placed in a container and carried to Pharaoh’s presence, where Moses then tossed it into the air. The act was to be a symbolic action much like those of the latter prophets (Jer 19 or Eze 4–5). There was also a logical connection between the soot created by the sweat of God’s enslaved people and the judgment that was to afflict the bodies of the en-slavers.

10–12 When the soot was tossed skyward, festering boils broke out on all the Egyptians and their animals. Attempts to identify this malady have produced various suggestions: (1) small pox, (2) Nile-blisters similar to scarlet fever, (3) skin anthrax, and (4) inflammations or blains that become malignant ulcers. Skin anthrax seems the most probable, since Dt 28:35 limits this plague principally to the lower extremities of the body. Furthermore, the black soot is especially suited, for anthrax (cf. anthracite coal) is a sort of black, burning abscess often occurring with cattle murrain.

The flies of the fourth plague have generally been blamed as the carriers of the anthrax spores, but they were totally removed at the conclusion of that plague. Presumably this was another generation of flies (depending on the temperature, another batch can come in twenty-seven to thirty-seven days). After animals or humans are bitten on the legs by these flies, a small bluish-red pustule with a central depression in the middle of the swelling appears after two or three days. The center of the boil dries up only to have new boils swell up, and the skin festers as if it had been burnt and then peels off.

In a humorous aside, v.11 notes that the magicians (who bowed out in plague three and are unnoticed, though possibly present, in plagues four and five) literally (and vocationally) “could not stand” before Moses. The same could be said for all the Egyptians. Here for the first time God hardened Pharaoh’s heart—a seconding, as it were, of his own motion made in each of the preceding five plagues.

8. Seventh plague: hail (9:13–35)

13–19 As in the first (7:15) and the fourth (8:20) plagues, Moses was to begin this plague by rising early in the morning to confront Pharaoh with the Lord’s message. From these early days in February until the time of the tenth and climactic plague, Pharaoh would spend approximately eight of the most dreadful weeks he had ever known.

To further underscore the theological significance of these weeks and their events, Moses was prompted by God to preface his latest announcement of divine judgment with a long message filled with doctrinal instruction. This unprecedented message was calculated to move Pharaoh and his subjects from rebellion to belief in the God of the Hebrews. Its ominous contents included (1) an announcement that God would vent the “full force” (i.e., “all the remaining plagues”) of his plagues on Egypt so that no one would doubt that there was anyone like this God in all the earth; (2) a reminder that previous pestilences and plagues might well have swept both king and people off the face of the earth had not God deliberately and purposely spared them for one very important reason: that God’s power and name would be heralded throughout the earth by means of Pharaoh’s stupidity; (3) a declaration that in denying the release of Israel Pharaoh had acted as an obstructionist against Almighty God himself; (4) a threat that Egypt would experience the worst hailstorm it had ever seen in its history; and (5) an extraordinary feature that provided for those Egyptians who believed Moses’ words were a means of escape from the effects of the storm.

The seventh plague was to be judgment with the expectation that it might result in the blessing of belief and trust. Had not Abraham been given this mission to be a means of blessing to “all peoples on earth” (Ge 12:3)? And has not the theme “that the Egyptians might know that I am the LORD” (or slight variations) appeared frequently in the midst of these plagues (7:5; 8:10; 9:14, 16, 29–30; and later in 14:4, 18)? Moses, like his Lord, would sigh of Israel (Nu 14:11): “How long will these people treat me with contempt? How long will they refuse to believe in me, in spite of all the miraculous signs I have performed among them?” The same words could apply just as well to Egypt.

The months of leniency were about over. Now the full blast of the ensuing plagues would penetrate directly to Pharaoh’s “heart” (v.14; NIV, “against you”). The “heart” (GK 4213) does not signify “his person” but rather his inner being, nature, and seared conscience. His pride and arrogance would be tossed to the wind as the terrors of these new plagues forced him in perplexed and desperate sorrow of soul to literally beg that the Israelites leave his presence immediately. Yet Pharaoh was no mere pawn to be toyed with at will, for the object was that he too might come to experience personally and believe (“know”) the incomparability of God’s person and greatness. The very superlative rating of his deeds—none “like it” (of the hailstorm in vv.18, 24; of the locusts in 10:6)—should have led the king and his people to the identical rating of God’s person (no one “like you” in 15:11 and “like me” in 9:14).

20–26 Rainfall comes so occasionally in Upper Egypt that the prediction of a severe hailstorm accompanied by a violent electrical storm must have been greeted with much skepticism. Only the delta receives on the average about ten inches of rainfall per year while Upper Egypt has one inch or, more often, none. But there were some who “feared the word of the LORD” and acted accordingly. Some Egyptians must have received Moses’ words as being from God himself; for they became a part of that mixed company who left Egypt with Israel (see 12:38).

Moses apparently lost his shyness and diffidence, for he was the one who now stretched forth his staff and his hand (cf. Aaron’s leading role in the first three plagues: 7:19–20; 8:6, 17). Hail joined by unannounced thunder and balls of fire that ran along the ground provided Egypt with the most spectacular display in her history. The destruction was devastating. Five times in vv.24–25 the word kol (“all,” “everything”) is used; yet it is used hyperbolically and not literally because the first two kols (“in all Egypt,” vv.24–25a; NIV, “throughout Egypt”) are immediately qualified to exempt the land of Goshen where Israel lived. Nevertheless, even though the storm did not take every single tree, herb, or creature in the field, it was tragic enough to impress the most callous individual.

27–30 Pharaoh, obviously shaken, conceded the point: “I have sinned,” though he included the face-saving qualifier “this time.” What made this plague any different from the rest—except its severity? Only when the Lord began to hurt Pharaoh did he (momentarily) seek him (cf. Ps 78:34). Like Jeremiah (Jer 12:1), Pharaoh declared that “the LORD” (i.e., Yahweh, not Elohim!) was in the right and that he and his people were in the wrong!

Moses’ reply was simple, confident, and noble. He would spread out his hands in prayer (a gesture of request and appeal to God) once he was back with his own people, and the hail and thunder would stop—to prove once again (in this repeated apologetic and evangelistic refrain) that the whole earth belongs to the Lord. “But,” Moses added, “I know that you and your officials still do not fear the LORD God.”

31–35 Since in Egypt flax is usually sown in the beginning of January and is in flower three weeks later while barley is sown in August and is harvested in February, both would be exceedingly vulnerable if this plague occurred in the beginning or middle of February (probably a little later than usual with a high Nile year). Wheat and spelt were also sown in August but were not ready for harvest until the end of March. That Goshen was unaffected by this storm matches the agricultural observations; for the Mediterranean temperate zone has these storms only in late spring and early autumn but not from November to March. Flax, of which there were several kinds, was used for linen garments. The vicinity of Tanis was ideal for producing it. Barley was used in the manufacture of beer (a common Egyptian drink), as horse feed, and by the poorer classes for bread.

After Moses’ prayer was answered, Pharaoh once again rescinded his offer and forgot all about his confession of sin and wrong.

9. Eighth plague: locusts (10:1–20)

1–2 For the first time we are told that Egypt’s officials were also as obstinate as Pharaoh; therefore the Lord had hardened all of them as well. But Moses was to find a lesson in this divine work of hardening. There follows, then, another theological preface to the eighth plague, just as Pharaoh had been served in 9:14–16 with a similar lesson prior to the seventh plague. The lesson for Israel was to be twofold: (1) to educate succeeding generations in how the Lord “dealt harshly” with the Egyptians and performed his miracles in their land, and (2) to thereby bring Israel to faith in the Lord.

3–6 Moses proceeded to the palace and announced to Pharaoh the next plague. The message began with a question: “How long will you refuse to humble yourself before the Lord?” His act of self-condemnation and abject humility in 9:27 was just that—an act. But here was the consummate question of all questions that God finally raises against all obstinate sinners: “How long?”

The demand for Israel’s release was again laid down along with a time lag that provided ample opportunity for reflection and repentance: “tomorrow.” Moses informed Pharaoh that God would “bring locusts into your country.” Joel 2:25 calls locusts God’s “great army.” They would finish off every living green thing, leaving destruction in their wake. It would exceed any locust invasion Egypt had ever known in the past. With that, Moses and Aaron turned their backs on Pharaoh (an amazing gesture for normal protocol) and stalked out.

7–11 Pharaoh’s officials picked up Moses’ “How long?” with a “How long?” of their own. Out of loyalty to their king and country, they blamed Moses; but it was obvious that they were beginning to become impatient with Pharaoh’s intransigence. Could Pharaoh not see the “snare” this man was setting for them, and did Pharaoh not realize that Egypt was about ruined? Someone had to give in. They urged Pharaoh to yield: “Let the people go.”

In another first, Pharaoh had Moses and Aaron return to the palace for some negotiations related to the imminent pestilence. Clearly as a sop to his frightened officials, Pharaoh half-heartedly gave Moses permission to take Israel to sacrifice in the desert. However, he coyly asked (as if he did not remember Moses’ original request or the advice just given him by his own officials), “Just who will be going [on this religious trip]?” Moses responded out of a position of strength: “We all are going to celebrate this festival to the LORD” (cf. v.9). “Oh no you are not,” was Pharaoh’s decisive rejoinder. “You take only your ‘men’; that will be enough for religious purposes.” It is true, of course, that later Israel required only her males to attend these three yearly festivals (23:17; 34:23; Dt 16:16), but the artificiality of this limitation at this time is evident since women normally accompanied the men at Egyptian religious festivals.