INTRODUCTION

1. Name

The name Deuteronomy results from a mistranslation of Dt 17:18. For the Hebrew “a copy of this law,” the LXX and the Vulgate have terms meaning “the second law” or “a repetition of this law.” Internal data locate the book as beginning in the desert east of the Jordan in Moab on the first day of the eleventh month of the fortieth year—forty years after the Exodus from Egypt (1:3). This was after Moses and the Israelites had defeated Sihon and Og, kings of the Amorites in Transjordan (1:4).

2. Character and Author

In addition to the many statements about Moses’ speaking these words are statements made within the book itself that indicate he was the author (cf. 1:5; 31:9, 22, 24, 30). Other OT books assert Mosaic authorship of Deuteronomy (1Ki 2:3; 8:53; 2Ki 14:6; 18:6, 12), as do Jesus and writers of the NT (Mt 19:7–8; Mk 10:3–5; 12:19; Jn 5:46–47; Ac 3:22; 7:37–38; Ro 10:19).

Deuteronomy can be approached from several angles: (1) as a “Book of the Law”; (2) as a series of addresses given by Moses, repeating much of the earlier legal material in the Pentateuch and adding various other elements; (3) as a covenant-treaty between the sovereign Lord and his people, similar in both form and content to other covenant-treaties that have been found in the ancient Near East (having a preamble, historical prologue, various laws, arrangement for depositing treaty copies and for regular reading of the treaty, witnesses, and curses and blessings); (4) as a compendium of directives that the Lord gives through Moses to the Israelites as they are about to enter Canaan. Of these four, it is primarily a covenant renewal document, to prepare the new generation of God’s covenant people to live responsibly and joyfully under the Lord’s rule in the Promised Land (i.e., the third purpose).

3. Purpose

The purpose of Deuteronomy is distinctly stated as “Hear, O Israel,” “These are the commands,” and “Be careful to do” (4:1–2, 5–6, 9–14, et al.). Such exhortations are often followed by reasons for obedience to the Lord. The basic existential occasion grew out of the rescue of the people from Egypt and their position on the southeastern border of Canaan—poised to enter and to occupy that land as their own in fulfillment of the promises first made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and now reiterated to the descendants of the I patriarchs. It was the intention of God to form their nation and give Canaan to them as their national homeland (cf. 6:18).

The book of Deuteronomy calls for the enactment (renewal) of the covenant as the Israelites prepared to enter Canaan to conquer and occupy it, and it presents the way of life that they were to follow in the Promised Land. Incidental to this covenant enactment are the curses that would fall on Israel if they failed to observe the stipulations and the blessings they would receive when they obeyed the Lord.

4. Theological Values

The theological values of Deuteronomy can hardly be exaggerated. It stands as the wellspring of biblical historical revelation. It is a prime source for both OT and NT theology. When the prophets speak of God, they speak of the God and the message of Deuteronomy and of the relationship embodied in its covenant-treaty. The warnings of doom in the prophets (esp. Jeremiah) are the warnings and curses of Deuteronomy. The promises of blessing for the Israelites when they live in faith, love, and obedience to the Lord are the blessings of Deuteronomy.

The way of life for the people of God forms the basis of all subsequent revelation of the way of life that is acceptable to him. God has redeemed his treasured inheritance from the bondage of Egypt, and he is about to fulfill his promise to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob by giving them the Promised Land. The later NT teachings on the love of God, the redemption offered through Christ, the saved as the inheritance of God, and the fulfillment of the promises of God to the saved as their inheritance from him rest on Deuteronomy.

God in this book is personal, eternal, omnipotent, sovereign, purposeful, loving, holy, and righteous. The knowledge of his person and will is communicated by propositional, directive, exhortative, informative, and predictive revelation. No other god exists.

The most important element of subjective theology in Deuteronomy is that of absolutely unqualified, total commitment of the people of the Lord. Nothing else is acceptable, especially no syncretism with other gods or other religious practices. The people belong to the Lord alone!

EXPOSITION

I. Preamble (1:1–5)

1–5 The terms used here indicate the nature of the book. “These are the words” suggests a suzerain-vassal treaty preamble. “All that the LORD had commanded him” indicates the source of the material in the book, the nature of Moses’ ministry as communicator of the Lord’s commands rather than that of an author, and the authoritative character of the addresses as commands of the Lord.

“The LORD [GK 3378],” “The LORD our God,” “The LORD your God,” “The LORD, the God of your fathers” (1:3, 6, 10, 11, et al.) all signify a strong emphasis on the Lord as the originator of everything that follows in Deuteronomy. He transcends any king (or any god) in the suzerain-vassal treaties (where gods are mentioned as empowering the kings), because he is not only superior to all other gods but he is the supreme author, enactor, and benefactor of the covenant-treaty.

A crucial, stirring moment in the experience of the new nation was at hand. It was time for the Israelites to realize the Lord’s promises from the past—a time for the fulfillment of the hope that began at the Exodus. The Lord’s concern—and Moses’—was to prepare the people for the conquest and occupation of Canaan. Now, on the brink of crossing the Jordan, Moses reviewed the salient historical events and Israel’s covenant-treaty with the Lord.

The geographical references in these verses were evidently known in Moses’ time. Perhaps these locations identify a few of the places where Moses had earlier imparted some of “these . . . words” to the people. Laban and Hazeroth appear to be two stations on the journey from Egypt to Canaan (Nu 33:18, 20–21). Mount “Horeb,” which is interchangeable with Mount Sinai, is used more often in Deuteronomy (1:2, 6, 19; 4:10, 15; et al.) but also occurs elsewhere in the OT. “In the fortieth year” marks the terminal point of the generation that disobeyed the command at Kadesh.

Sihon and Og were kings of Amorite peoples (cf. 2:24–3:11; ZPEB, 1:140–43). Heshbon was the capital city of Moab, but Sihon had captured it and made it his capital. Bashan was the territory east of the Lake of Galilee. Ashtaroth, Og’s capital, was a little more than twenty miles east of the Lake of Galilee while Edrei, where Israel defeated Og, was a little less than twenty miles southeast of Ashtaroth. Canaan proper, west of Jordan, is labeled “the hill country of the Amorites” (vv.7, 19, 20, et al.). Sihon controlled southern Transjordan and Og the northern sector, mainly the area east of the Lake of Galilee. So here, “east of the Jordan,” Moses began his sermon.

II. First Address: The Historical Prologue (1:6–4:43)

A. Experiences From Horeb to the Jordan (1:6–3:29)

1. The command to leave Horeb (1:6–8)

6–8 Moses began by reciting God’s order to leave Horeb and go to Canaan, though what the Lord commanded the people was a new bit of information (its content is given only here; cf. Nu 10:11–13). The Lord’s gift of Canaan to Israel and his command to them to enter and to possess the land are cardinal elements of the book. The description of the extent of the land coincides with that promised on oath to the fathers (Ge 15:18). The geographical terms delimit the land by sections: “The Arabah” is the Jordan Valley from Lake Galilee to the area south of the Dead Sea; “the mountains,” the central hill country; “the western foothills,” the slopes toward the Mediterranean; “the Negev,” the area north of the Sinai peninsula but south of the central hill country; “the coast,” the land along the Mediterranean; “the land of the Canaanites” and “Lebanon, as far as . . . the Euphrates,” the northern section.

The promise of the land was given “to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob—and to their descendants.” The land, then, first promised to Abraham, was given Isaac as the “only” son of Abraham and Sarah and then limited to Jacob and his sons, the heirs of the promise (Ge 12:7; 15:18; 26:3–4; 28:4, 13–15). This promise was reaffirmed at the burning bush (Ex 3:8, 17).

2. The appointment of leaders (1:9–18)

9–14 The increased number of Israelites presented too many problems for Moses to care for alone. Consequently, political and juridical appointments were initiated. No mention is made here of the instigation of this procedure by Moses’ father-in-law (cf. Ex 18:13–26); here Moses simply stated that he saw the need for “judges” [GK 9149] in political and judicial activity as his assistants. While Exodus suggests that Moses himself appointed these leaders, it is apparent from v.13 that the people chose the leaders as representative of the various tribes, and then Moses appointed them to their several tasks (vv.15–18). The leaders were to be characterized by wisdom, understanding, and experience.

15–18 The use of the word “commanders” [GK 8569] and the size of the groups—thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens—suggest a military arrangement. The need, however, was for assistant judges, not for military men. The context begins and ends with reference to a judicatory. The designation of these men as commanders, tribal officials, and judges seems to indicate three distinct classes. This arrangement seemed to be satisfactory to the people.

Four matters regarding the administration of justice are mentioned: (1) disputes between fellow Israelites or with foreign inhabitants in the land were to be arbitrated; (2) directives for making decisions include no partiality—small and great were to be heard on an equal basis; (3) judges were not to fear human beings because juridical process rested on the realization that “judgment belongs to God”; and (4) cases too difficult for the judges were to be referred to Moses.

3. The spies sent out (1:19–25)

19–23 After leaving Horeb, the Israelites went “as the LORD . . . God commanded” (cf. v.7) toward the hill country of the Amorites. This difficult journey of more than 150 miles through the Desert of Paran brought them to Kadesh Barnea on the southern perimeter of the Land of Promise. “That vast and dreadful desert” was a forbidding limestone plateau: hot, dry, rugged, and usually bare of any sustainable vegetation. There Moses reiterated the Lord’s command (v.8) to take possession of the land God was giving them and exhorted them not to be afraid, obviously indicating that the Israelites were afraid. The people suggested that some men be sent into the land to scout it out. In light of Nu 13:1–3, apparently the people first suggested that this reconnoitering be made; Moses then approved the idea, referred the request to the Lord who agreed to it, and ordered that each tribe send out one representative.

24–25 Moses, recalling that event, left out details and descriptions, saying only that the spies returned with a report that the land was good and that they brought back some fruit from the Valley of Eshcol as evidence (cf. Nu 13:3–33).

4. The rebellion against the Lord (1:26–46)

26–31 In spite of the good report and evidence of the productivity of the land, the people refused to enter because the rest of the report discouraged them. The size and strength of the inhabitants, the high fortifications of their large towns, and the presence of the Anakites made the Israelites so fearful that they rebelled against the Lord, misconstrued his attitude toward them, and refused to believe in his promises. Grumbling in their tents, they said, “The Lord hates us,” when in truth he loved them. They claimed that the LORD brought them from Egypt to have them destroyed by Amorite hands; but the contrary was true. Again Moses urged the people not to be afraid, asserting that the Lord their God would go ahead of them as he had in Egypt and Sinai. Before their very eyes God had carried them along (cf. Nu 11:12).

32–36 In spite of the promise of the Lord’s leadership, the people refused to enter the land; so the Lord declared that they would not see that good land. Out of the vast throng of Israelites, only those under twenty, plus Caleb and Joshua, would enter it (cf. Nu 14:30–31). Caleb “followed the LORD wholeheartedly”; he was totally committed to the Lord and obeyed him fully. God promised him the area he had explored.

37–38 Moses told the people that the Lord was angry with him also “because of you”; so Moses himself would not be allowed to enter the land. This must refer back to the experience of the Israelite quarrel with the Lord at the waters of Meribah (Kadesh). There the Lord said that Moses and Aaron would not enter the land because they did not honor him (Nu 20:12). Moses here looked behind his own failure and referred to the cause of his action: the people’s criticism of the Lord’s provision of food. Joshua is called Moses’ assistant (lit. Heb., “he who stands before you”); he would lead the Israelites in taking the land.

39–40 The children of this rebellious generation would acquire the country that that generation had faithlessly failed to invade and possess. That generation was condemned to return to the desert. The way of the Red Sea was doubtless a well-known route through Sinai and does not necessarily imply destination.

41 Being sent back into the vast, dreadful desert (v.19) was more than the people could take; so they confessed their sin, put on their weapons, and presumptuously went up into the hill country. This admission of their guilt was frivolous. Without due consideration of the Lord’s later command, their action of going up into the hill country, now without the Lord’s approval, was foolhardy.

42–43 Not only did the Lord declare that he would not go with the people, he also prophesied their defeat. But the Israelites’ obstinacy was such that they would not listen; so they marched up to battle against the Amorites in an action of presumption, rashness, and arrogance.

44–46 The Amorites met the Israelite army somewhere north of Kadesh Barnea and then routed the Israelites toward the south or southeast. The Amorites’ pursuit “like a swarm of bees” describes numerical greatness, persistence, and ferocity. “You came back and wept before the LORD” means that the Israelites returned to the tabernacle of the Lord and wept there. The Hebrew time phrase in v.46 expresses a long, indefinite period and suggests that a large part of the next thirty-eight years was spent there.

5. The journey from Kadesh to Kedemoth (2:1–25)

1–7 In obedience to the Lord’s command in 1:40, the chastised Israelites returned to the desert, between Kadesh and the Seir range. The period probably encompassed both departures from Kadesh recorded in Nu 14:25 and 20:22. The phrase “for a long time” (cf. 1:46) suggests that the time spent at Kadesh and around Seir took up the period between the abortive attempt to enter Canaan from Kadesh and the end of the wanderings that brought them to the Jordan River opposite Jericho. It was a “long time” because the Lord had decreed punishment on the nation for their disobedience at Kadesh.

If the command to go northward was given in Kadesh, then the order gives the general direction only, for it was necessary to go south and east before marching north. With the exception of Caleb, Joshua, and Moses, the generation of men twenty years old or more who had refused to enter Canaan at the Lord’s command were now dead (vv.14–15); and Moses also would die soon. Therefore, the Lord said that they had gone around the hill country long enough.

Approaching Edomite lands brought Israel in or near the area the Lord had promised to Esau and his descendants. So the Lord commanded the Israelites not to make war on their Edomite relatives; neither were they to take their land or anything in it; they were to buy food and drink with “silver.” Before this the Israelites had lived off what the Lord had supplied. Manna did not completely cease until the day after the first celebration of the Passover in Canaan under Joshua (Jos 5:10–12; cf. Ex 16:35).

8–9 The order of the journey reviews the travel from Ezion Geber or Elath at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba northward to the plains of Moab. As the Lord had forbidden Israel to attack the Edomites because they were blood brothers, so now he warned them not to fight with the Moabites. They were descendants of Lot, and he had given them the land they controlled.

10–12 The mention of these territories elicited historical references to former inhabitants, which the Moabites (vv.9–11), Ammonites (vv.19–21), Edomites (vv.12, 22), and Caphtorites (v.23) had displaced. These ancient nations are described as numerous, tall, and strong. Yet they were destroyed by invading brothers of the Israelites—surely a suggestion that Israel too would succeed in conquering the land they were about to invade. The reference to Israel’s destruction of former inhabitants may indicate the point of view of Moses referring to the conquest of Transjordan.

13–15 Since the fighting men of the generation that had failed to enter the land had died off, the Lord’s hand was no longer against Israel. He directed the new generation to cross the Zered, which flows into the southern end of the Dead Sea from the east, and then to cross the Arnon (v.24). This brought them into the area controlled by the Amorites.

16–19 When the Israelites came near the northeastern border of Moab at Ar, they were next to the territory occupied by the Ammonites, who at that time lived east of the Amorites. Sihon controlled the area between the Arnon River on the south, the Jordan on the west, the Jabbok on the north, and the border of the Ammonites on the east. The Israelites were not to disturb the Ammonites but were to turn northwestward into the country of Sihon. The Ammonites were the descendants of Lot, and the Lord had given that country to Lot and his descendants (see comment on v.9).

20–23 This parenthetical portion mentions how the Lord had destroyed the Zamzummites (a nation of large people who could be called giants; cf. 3:11) and had given their land to the Amorites. He had also destroyed the Horites, the Avvites, and the Caphtorites and had given their land to the descendants of Esau. Evidently the Lord through Moses was establishing belief in his control over the Canaanite groups of the past to inspire Israel for the conquest ahead.

24–25 While Israel was not to disturb the Edomites, Moabites, or Ammonites, such prohibition did not extend to the Amorites. The Lord declared that he had put Sihon and his kingdom into Israel’s hands. The conquest was certain; it was only for Israel to accomplish it. They were to cross the Arnon into Amorite territory and confidently engage Sihon’s army in battle. God would put the fear of Israel into all the nations in the area (Cf. 11:25; also Ex 15:15–16; 23:27).

6. The conquest of Transjordan (2:26–3:20)

a. The defeat of Sihon (2:26–37)

26–35 Though the Lord had said that he had given Sihon into Israel’s hands (v.24), Moses approached Sihon with messengers bearing a request to pass peaceably through his country. But Sihon, from a heart made stubborn by the Lord, refused the request and came out to battle against the Israelites. Sihon, his sons, his army, his people, and his towns were destroyed. So southern Transjordan was subjected to total destruction, except that the Israelites kept for themselves the “plunder” instead of giving it over to the Lord by destruction. Such exceptions were not allowed when the Lord required a strict following of the total-destruction principle (cf. Jos 7; 1Sa 15).

36–37 So all the territory from the Arnon Gorge on the south to Sihon and Og’s boundary in Gilead on the north, and from the upper course of the Jabbok River on the east to the Jordan on the west fell to the Israelites. They did not, however, encroach on any of the Ammonite land, which the Lord expressly commanded them to avoid (see v.19).

b. The defeat of Og (3:1–11)

1–3 The conquest continued by pressing north to engage Og king of Bashan in battle because the Lord had signified that his army and territory would also become Israel’s. Og was vanquished; and both population and cities were destroyed, but the livestock and valued goods were kept by the Israelites (v.7).

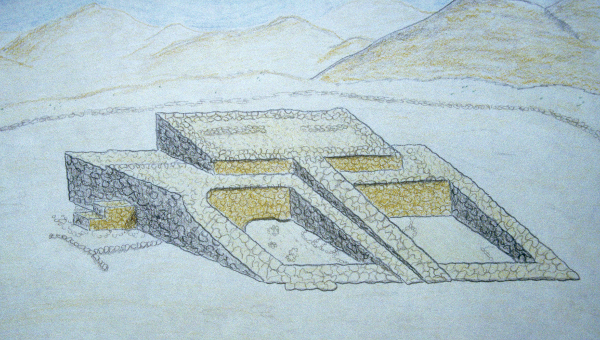

4–7 The geographical limits of the country of Og that was conquered are in general clear, though certain specific designations are not. The description of the sixty cities as “fortified with high walls and with gates and bars” indicates that they were formidable obstacles and that their capture was a remarkable success (cf. Nu 32:33; Jos 9:10; Pss 135:10–11; 136:18–22). “City” (GK 6551) need not imply a place with a large population; some cities had a population of only a few hundred.

8–11 Prior to allocating the captured lands to the Reubenites, Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh, Moses described the whole area taken from the Amorite kings. The names Sirion and Senir for Mount Hermon occur elsewhere in the Scriptures (1Ch 5:23; Ps 29:6; SS 4:8; Eze 27:5). Salecah and Edrei apparently fix the southern border of Bashan. His iron bed might have been a black basalt sarcophagus, many of which have been found in that country.

c. The division of the land (3:12–20)

12–15 The geographical description of the territories given to the two and a half tribes is difficult to follow in its entirety. In the NIV this half of the tribe of Manasseh is called “the half-tribe of Manasseh”; Makir was their progenitor (cf. Nu 26:29; 32:40). The other half, which received its allotment in Canaan proper, is not mentioned as often and is not designated “the half-tribe of Manasseh.” The Geshurites and Maacathites were two smaller kingdoms that Israel did not drive out. Those people continued to live on their land under Israel (Jos 13:11, 13).

“The rest of Gilead” (v.13; a northern part other than that given to Reuben and Gad) is given to the half-tribe of Manasseh (simply “Gilead” in vv.15–16). Gilead sometimes refers to the area between the Jabbok and the Yarmuk (the northern sector), sometimes to the central area south of the Jabbok but north of Heshbon and the Dead Sea, and sometimes to the area including both sections. Jair’s area was in the northern sector of Gilead, beyond the Yarmuk Valley up to the territory of the Geshurites and Maacathites who occupied the land east of Lake Galilee and the Waters of Merom. The boundary between Gilead and Bashan is not clearly defined. The territory of Jair seems to be in both Gilead and Bashan.

16–17 Verse 12 says that the Reubenites and Gadites’ area included half the hill country of Gilead. This makes the southern part of Gilead the northern part of Reuben and Gad, the southern border of Reuben and Gad being the Arnon Valley, and the eastern border being the Jabbok River from its headwaters in the south. The eastern border continues northward until the river bends and flows westward to the Jordan. Its western border was that part of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea that closed the gap between the northern and southern borders.

“Kinnereth” (cf. Gennesaret in Lk 5:1) is an older name for Lake Galilee, a town on its northwest perimeter, or the entire area. The western border of the Gadites and Reubenites’ allotment extended from Kinnereth along the Jordan and the eastern side of the Dead Sea as far as the Arnon Gorge, approximately half the length of the sea.

18–20 Moses reminded the men of the two and a half tribes of their responsibility to cross the Jordan with the rest of the Israelites to win the land there before they settled down in their Transjordanian possessions. All the “able-bodied men” had to represent a special body of soldiers. Surely some men, also armed, must have remained in Transjordan to protect the women and children.

7. Moses forbidden to cross the Jordan (3:21–29)

21–29 After encouraging Joshua with the assurance that God would fight for him in Canaan as he did in Transjordan, Moses referred to his appeal to God that he might go into “the good land beyond the Jordan.” The Lord refused this request (cf. 1:37; 3:26; 4:21) and directed him to ascend to the top of Pisgah so that he might look over the Promised Land, even though he would not enter it; this was fulfilled after Moses had delivered the messages of Deuteronomy (see 31:7–8, 14, 23). Joshua, not Moses, was to lead the people in conquering the land.

B. Israel Before the Lord (4:1–40)

1. Exhortation to obey the Lord’s commands (4:1–14)

1–2 Moses next turned to the stipulations of the covenant-treaty. This beginning section is largely hortatory, though what the Israelites were exhorted to do necessitates introductory reference to the stipulations. Moses emphasized the importance and necessity of adhering to the codes that the Lord had given the people. What he declared was sufficient to guard their lives and to guarantee their possession of the land. The phrase “I am about to teach you” indicates the nature of the Deuteronomic messages. Coupled with these expositions of the law are the exhortations to “follow” (GK 6913) the laws and to “keep [GK 9068] the commands of the LORD.”

3–6 Failure to follow the Lord would result in death (cf. Nu 25; cf. Ps 106:28; Hos 9:10). “Baal Peor” designates both the place and the god of the place. The worship of the Canaanite Baal involved sexual acts and continued to be a serious breach of the first commandment among the Israelites and, consequently, of the covenant. Loyalty to the Lord was an absolute requirement for those who would follow him; failure to heed the warnings about the “other gods” of Canaan would result in immediate destruction. Only those who held fast to the Lord could expect to remain alive. Obeying the Lord’s codes would also make them known to the nations, who would esteem the Israelites as wise and understanding people.

7–8 Moses pointed up the distinctive character of these codes: the Lord was near them when they prayed, and no other nation had such righteous laws. Since these laws were communicated through prayer, the giving of them brought Israel close to God. The Lord’s presence in the center of the camp was symbolized in the glory over the ark of the covenant and the tabernacle (tent) in which the ark was placed and in the pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night (Ex 40:34–38; Nu 23:21).

9–14 Moses was concerned that the generations to follow would be taught what he was teaching to the people; this communication involved memory and observance. But knowledge was not enough; the people had to “follow them” (vv.1, 5, 13–14) and “observe [GK 6913] them carefully” (v.6). Active obedience was essential. Israel was called on to remember the day at Horeb (Sinai) when the Lord spoke to them “out of the fire.” They were to remember his presence through “the sound of words . . . only a voice.” This is elaborated further by such terms as “his covenant [GK 1382], the Ten Commandments,” and as what was written “on two stone tablets.” The “Ten Commandments” epitomize all the commands that the Lord gave to Israel through Moses. The “two stone tablets” are two tablets, each inscribed with the list of commands. This coincides with the two copies of a suzerain-vassal treaty, which each participant was to have.

2. Idolatry forbidden (4:15–31)

15–18 As an introduction to the exhortation to shun idolatry, Moses repeated his observation (v.12) that the people saw no form when the Lord spoke to them from Horeb. Because he has no physical form, no physical representation could be tolerated. The description of the forms of creatures is slightly more explicit than that in the second commandment (Ex 20:4; Dt 5:8) and reminiscent of the Creation narrative (Ge 1:20–26). The Lord is not like the idols of Canaan.

19 Neither were the Israelites to worship the sun, the moon, and the stars. “Things the LORD your God has apportioned to all the nations under heaven” cannot mean that God gave these celestial bodies to the nations as objects of worship. Rather, these were given to all humankind for the physical benefit of the earth and were not proper objects of worship at all (Ge 1:14–18).

20 The use of metal by heating certain ores and then hammering the metallic residue or welding it to other parts while still hot may have appeared in the Near East in the first half of the third millennium B.C., but the manufacture of iron objects (usually weapons) was limited till 1500 B.C and later. Bringing Israel out of Egypt was like bringing her out of an iron-smelting furnace—the heavy bondage of Egypt with its accompanying difficulties and tensions being likened to the hottest fire then known. Israel had been brought out of Egypt “to be the people of his inheritance,” as they indeed were (cf. Ps 78:62, 71; Isa 19:25).

21 Moses, however, was to die in Moab; and for the third time he referred to the Lord’s refusal to let him cross the Jordan and enter Canaan proper (1:37; 3:26–27). Each time he spoke of the Lord’s anger toward him “because of you.” Moses seemed to feel that the Israelites were to bear the blame for his predicament. Certainly the repetitious reference to the Lord’s prohibition reflects his keen disappointment.

22–24 Since the people were about to enter the land, Moses reiterated his exhortation that they be very careful not to forget the covenant the Lord made with them. The central character is the Lord himself, who is “a consuming fire,” intolerant of idols in any form (5:9; 6:15; Ex 20:5; 34:14; cf. Jos 24:19; Na 1:2).

25–29 The spirit of the prophets moved in Moses as he looked into the future of Israel relative to idol worship. Seeing that the generations to come might become corrupt through idolatry, he called heaven and earth as witnesses of his warning of destruction against the Israelites, the scattering of them among the nations, and their extremely limited numerical survival. He seemed sure that such a situation would prevail because he proceeded to tell how, in those foreign lands, the Israelites would “worship man-made gods” but eventually would seek and find the Lord their God. The Lord would not abandon, destroy, or forget them—or forget his covenant with them (cf. vv.29–31). This indictment of idolatry portrays the spiritual nature of Deuteronomy. Idols have no senses but are only human fabrications using common, insensate materials. The only way out of any future predicament resulting from infidelity rested on unequivocal recommittal to the Lord (cf. 6:5; 10:12; 11:13; 26:16; 30:2, 6, 10).

30–31 The nation may fail to uphold the covenant; the people may forget their Lord; but when they turn back to him in faith and obedience, he will mercifully accept them. He will not forget the covenant based on his promises.

3. Acknowledgment of the Lord as God (4:32–40)

32 Waxing eloquent as he tried to press home the greatness of the Sinaitic experience, Moses grandly asserted by a series of questions that the revelation of the Lord at Horeb was the greatest event of history. From the creation of humanity until that time, nowhere else on earth had such an observable event happened.

33–38 God had spoken to the people out of the fire, and they still lived! Moses described what the Lord had done for them in Egypt and through the deserts. The “testings” (GK 4999) probably relate primarily to the plagues or “great trials” (cf. 7:19). This “testing” is immortalized in the experience at Rephidim where the Israelites tested the Lord’s patience by asking, “Is the LORD among us or not?” (Ex 17:7). The more or less synonymous expressions in v.34 indicate the extraordinary display of the Lord’s power. They all indicate that the Lord is God and that he is stronger than the gods of Egypt. Moreover, all these “awesome deeds” had been done for them “before [their] very eyes” with a specific intent. They were to (1) learn that he was the only true God, (2) be corrected of any false notions or wrong behavior, and (3) be prepared for entrance into the land of their inheritance.

The Lord’s love for his people finds its first mention here. The reference to the Lord’s choice of Israel, based on his love for their forefathers, and the reference to his gift of Canaan to them as an inheritance go back to the covenant with Abraham and to the promises of that covenant (Ge 12:3; 17:4–8; 18:18–19).

39–40 Moses again emphasized personal commitment to the Lord, based on the fact that he is the only God and that he exists both in heaven and on earth. Such a commitment would result in prosperity and continued possession of the land that the Lord was giving them. The Hebrew structure of the last clause in v.40 suggests purpose rather than result—in order that you may continue to live in the land.

C. The Transjordanian Cities of Refuge (4:41–43)

41–42 Bezer, Ramoth Gilead, and Golan are designated as sanctuaries—elsewhere “cities of refuge”—for whoever unintentionally and without premeditation killed someone (cf. 19:1–13; Nu 35:9–28). Only here are the names of the Transjordanian cities of refuge expressly mentioned (but see Jos 20:8).

43 The desert plateau extends eastward from the upper part of the Dead Sea. Bezer lies about twenty miles east of the northeast corner of the Dead Sea. Ramoth Gilead was about thirty miles southeast of Lake Galilee, and Golan, twenty miles east of a centerpoint on the east bank of Lake Galilee. Bezer, then, was accessible to the people in southern Transjordan, Ramoth Gilead to those in the central part, and Golan to the ones in the north. The identification and location of these places are not certain.

III. The Second Address: Stipulations of the Covenant-Treaty and Its Ratification (4:44–28:68)

A. Introduction (4:44–49)

44–49 As an introduction to the stipulations, this paragraph presents something of the character of what follows—namely, “stipulations, decrees and laws.” It mentions also the people, the time, the place, and a brief description of the extent of the lands they had captured.

Why another introduction? (Notice 1:1–5.) Perhaps this follows the procedure of updating the treaty at treaty renewal time. It may be an instance of the repetitive character of Deuteronomy as a device for emphasis and instruction.

B. Basic Elements of Life in the Land (5:1–11:32)

1. The Ten Commandments (5:1–33)

a. Exhortation and historical background (5:1–5)

1–2 Moses’ main address begins much as his introduction to the historical prologue (4:1). He urged the people personally to learn these decrees and laws and to adhere to them. He reminded them that they themselves had received the covenant from the Lord who had spoken to them out of the fire on Mount Horeb. Though the people he was then talking to were less than twenty years old (except for Caleb and Joshua) at the time of the Horeb experience, they were there and were now representative of Israel. The covenant-treaty was made by the nation represented at Horeb, and the covenant remained in force to all succeeding generations until abrogated or qualified by the Lord.

3 The “fathers” (GK 3) were not the people’s immediate fathers but their ancestors, i.e., the patriarchs (see 4:31, 37; 7:8, 12; 8:18).

4–5 The immediacy of the Lord’s relationship with the people is pointed up in the phrase “face to face” (cf. 34:10; Ex 33:11; Ge 32:30; Jdg 6:22). However, Moses explained that this relationship came through his mediatorship, because of their fear of the fire on the mountain. The character of Moses’ mediation can be seen in the contrast between the Israelites’ hearing the sounds of the voice of God (4:12, 15; 5:4, 22, 24; 10:4) but not with sufficient clarity to distinguish the words (Ex 19:7, 9; 20:19, 21–22; cf. Ac 9:7).

b. The commandments (5:6–21)

6–7 The Ten Commandments sit appropriately at the beginning of Moses’ elucidation of the basic legislation for the Israelites. These commands are not only to be learned but also to be obeyed. They come directly from the Lord their God, who brought them up from Egypt. Their relationship with God is rooted in history, and that history is one of God’s interventions for their benefit. The phrases “other gods” and “before me” also speak of the relationship of the people to God. God does not allow his people to have “other gods”—whatever they might be.

8–10 The proscription of making or using idols is total. Nothing in Israel’s environmental experience may be the basis for an idolatrous form to be honored and worshiped as God. The reason is definitely personal, both on the part of the Lord and on the part of the people. The people either hate the Lord or love and obey him, and they receive from him punishment or love commensurate with their hate or love and obedience. Those who adhere to the covenant-treaty stipulations get its promised benefits; those who do not adhere to them get its punishments.

The children of Israel are not punished for the sins that their fathers committed; they are punished for their own sins (cf. 24:16). The punishment, however, goes on “to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me,” just as his love continues toward “a thousand [generations] of those who love me and keep my commandments.” The distinction between punishment to the third and fourth generation and love extended to thousands suggests that God’s love far surpasses his retribution.

11 The third commandment concerns the use of the name of the Lord God in oaths or vows. Oaths were part of the common process of making authoritative and firm statements or promises. The Israelites were not to use the Lord’s name to seal such declarations in a light or frivolous manner or without the intention of fulfilling the oath, vow, or promise. The “misuse” of the name of the Lord for an unworthy cause or in an unworthy manner destroys the proper use of that name in prayer, praise, and thanksgiving; and it substitutes a blasphemous manipulation of witchcraft and other supposed sources of power for a holy invoking of God’s name (cf. 18:9–14; cf. also Mt 5:33–37; Jas 5:12).

12–15 In the commandment on the Sabbath day, the emphatic statement “as the LORD your God has commanded you” looks back to the initial declaration in Ex 20. The prohibition against making animals work on the Sabbath is also more emphatic here than in Ex 20:10. All the Israelite animal holdings are included in “any of your animals.” Moses’ concern for the lower strata of society is tied to the exhortation to remember that the Israelites themselves were slaves in Egypt. The Lord’s bringing them out of Egypt does not preclude other reasons for the law of the Sabbath—as God’s rest on the seventh day (after Creation; Ex 20:11). The words “may rest, as you do” indicate concern for others’ well-being.

Ideas involved in the observance of the Sabbath are perpetuated in the NT by the analogy of the creating of a new people of God through the ministry of the Lord Jesus. The ritual elements of the Jewish Sabbath are superseded by the work of Christ and by faith in him. And the time reference has changed to the first day of the week, now called the Lord’s Day, to focus on the new life effected and epitomized by the resurrection of Christ Jesus (Mt 28:1–7; Mk 16:1–6; Lk 24:1–6; 1Co 16:2; Rev 1:10; cf. Eph 2:4–10; 4:24). However, even now the observance of the Lord’s Day must be in keeping with Col 2:16–17 (cf. Jn 20:1, 19, 26; Ac 2:1; 20:7).

16 To “honor” (GK 3877) one’s parents is to respect, glorify, and venerate them. Children are to hold parents in high regard because of their position in the family, a position not only in God’s scheme of authority in human relationships, but also in the covenant relationship that called for continuation of the people’s status with the Lord. Children’s regard for their parents led to regard for their parent’s relationship to God. Both father and mother are to be honored. The results of failure to honor parents can be seen in the law concerning an incorrigibly rebellious son (21:18–21).

The apostle Paul referred to the fifth commandment as “the first commandment with a promise,” the promise being “that it may go well with you and that you may enjoy long life on the earth” (Eph 6:2–3; see comment). The honoring of father and mother, together with its promise, carries over into all time and everywhere. However, the promise of an ultimate resting place (homeland) reaches its greatest fulfillment in “a new heaven and a new earth” (2Pe 3:13; Rev 21:1).

17 The NIV correctly translates the sixth command as a prohibition of murder rather than of killing. Murder is a personal, capital crime. Killing may be done as representative of the nation in judgment on a criminal or in war. In OT times persons were put to death in obedience to the command of God, but private or personal killing is murder and is proscribed.

Capital punishment is the penalty for willful homicide (Ge 9:6; Ex 21:12; Nu 35:16; Dt 19:12), the worshiping of other gods (Dt 17:2–7), and other acts of disobedience to the Lord (Dt 22:22; Jos 8:24–26; et al.). The Ten Commandments do not allow pandering the criminal who takes the life of a fellow human. Yet the person who accidentally kills another is protected (4:41–42). So the covenant-treaty restricts the passions that lead to murder but requires proper punishment of criminal homicides.

18 The starkly simple sentence “You shall not commit adultery” carries an immense load of social and spiritual implications and provides the basis for the later development of these implications. The marriage relationship continues throughout the OT as a figure of the covenant relationship between the Lord and his people (cf. Jer 3:8–9; Eze 16:15–63; Hosea). Apostasy is spiritual marital infidelity (figuratively), and total commitment must be Israel’s relationship to the Lord; human marriage under the covenant must be marked by the same faithful commitment (cf. Lev 20). Jesus declared that lustful thoughts also constitute adultery (Mt 5:27–28).

19 Throughout Scripture thievery is condemned. The right to personal property is basic to the whole Mosaic economy. The indictment of the eighth commandment extends to both kidnapping (stealing a person) and the theft of goods. The protection granted by the eighth commandment is still essential to a free society; the freedom from involuntary servitude and the right to hold property are protected by this law against theft. The commandment involves spiritual values also, which rest on the covenant relationship that the Lord proffers to his people.

20 Truth was an important matter in Israel. God is “the God of truth” (Isa 65:16; cf. Ps 119:142, 151), and he hates “a lying tongue” and “a false witness” (Pr. 6:17, 19). Judges were required by the Lord to make their decisions on the basis of truth (1:16–17). False testimony brought severe penalty (cf. 19:15–21). Both here and in Ex 20:16 this commandment is directed to bearing false witness against one’s neighbor (i.e., another Israelite).

21 The last commandment goes beyond what people do; it probes into their minds and desires. The prohibition against coveting catches wrongdoing at its source. Coveting stems from the seat of one’s soul, from one’s intentions, from one’s motivations, from one’s “heart.” The prohibition against coveting a neighbor’s land would have no meaning if family rights in marriage ties, domestic tranquility, and property ownership did not exist. To ensure family rights after Canaan was allotted, the Lord forbade coveting not only a neighbor’s wife, servants, animals, and whatever other goods he owned, but also his house and land, neither of which any of them had at that time.

c. Ratification of the covenant-treaty (5:22–33)

22 Moses’ declaration that these commands alone were spoken to the Israelites directly by God makes them more emphatic. The rest of the stipulations were given to Moses, who in turn gave them to the Israelites. The Ten Commandments constitute the basic behavioral code of the people and of all succeeding generations as well. No other short list of commands begins to compare with the effect that these have had in world history. In spite of being constantly broken, they stand as the moral code par excellence.

23–28 Moses referred to a strange inconsistency of the leaders of Israel that necessitated his mediatorial ministry. They acknowledged that they had seen the Lord’s glory and majesty and had heard his voice and yet remained alive. Nevertheless, they were afraid that continuous exposure would cause their death. No reason for this contradiction was offered, but they wanted Moses to be their intermediary. They asserted that they would do whatever God told Moses they should do. Moses reminded them that the Lord had accepted this arrangement, and Moses became the intermediary for the establishment of the covenantal stipulations. The people accepted that covenant (Ex 20:19; 24:3).

29–31 The best interests of his people are deep in the heart of God. He is a God of compassion, not vindictiveness. This glimpse into his heart is in harmony with the most compassionate depictions of Christ in the NT. The Israelites were directed to return to their tents. However, at the direction of God, Moses stayed to receive additional commands, decrees, and laws for the people to follow in the land.

32–33 Before once again stating and explaining the specific laws, Moses urged the people to do exactly what the Lord had commanded. The result of obedience would be long residence in the land of Canaan. Individual longevity may not be precluded from this promise for following the Lord, but the main reference was to the national welfare (cf. 6:2).

2. The greatest commandment: Love the Lord (6:1–25)

a. The intent of the covenant (6:1–3)

1–3 As the intermediary between the Lord and the people, Moses began to teach them what the Lord wanted them to do in the land across the Jordan. They and their descendants should “fear” (GK 3707) the Lord throughout their lifetimes. Standing in awe of God and holding him in utmost reverence and respect are essential to the understanding of “fearing God.” The reason for Moses’ teaching is elaborated by explaining why the people should hear and obey: to insure the nation’s well-being and to increase in number and wealth. “A land flowing with milk and honey” describes a land of plenty, a land of fertility.

b. The greatest command: total commitment (6:4–5)

4–5 The ineloquent Moses (cf. Ex 4:10) was used of the Lord to give the world some of the most eloquent declarations in all the history of speech when he extolled the being and nature of the Lord and described the relationship that his people should have with him. Various interpretations have been given to the shema (lit., “Hear”; GK 9048). Does the text teach monotheism? or monolatry for Israel? Or does it teach only a uniqueness in the Lord as over against various Baals and gods of other peoples? Some of the Israelites believed in the reality of other deities, but this declaration of the nature of the Lord does not admit of the real existence of other gods. The Lord is the only deity.

While the primary assertion is that there is only one true God, it is also asserted that this true God is Israel’s God. Thus, the Israelites should acknowledge no other god. The Lord cannot be known or acknowledged in many forms like the Canaanite Baals. There is only one Lord, and he alone is God, and they have entered into a covenant-treaty with him.

The exhortation to love “with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength” indicates the totality of one’s commitment in the purest and noblest intentions of trust and obedience toward God. The words taken together mean that the people are to love God with their whole selves.

Jesus taught that Dt 6:4–5 constituted the first, the greatest, and the most important commandment, and that by obeying it one would live (Mt 22:37–38; Mk 12:29–30; Lk 10:27).

c. Propagation of the command (6:6–9)

6–9 The people were not to concern themselves only with their own attitudes toward the Lord but were to impress them on their children as well. They were to talk about God’s commands always, whether at home or on the road. Since in Ex 13:9–16 the consecration of the firstborn is said to be “like a sign on your hand and a reminder on your forehead that the law of the LORD is to be on your lips” (v.9), it would seem that here also the tying of these words as symbols on their hands and binding them on their foreheads and writing them on their doorframes and gateposts should be taken metaphorically or spiritually rather than physically. The symbols drew attention to the injunctions in vv.5–7.

d. Ways to preserve the command (6:10–25)

10–12 Again Moses gave a warning in the context of history. The land that was to be Israel’s had been promised years before to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. This promise was to be fulfilled in Israel’s experience. It involved much wealth: barns, houses, wells (cisterns), vineyards, and olive groves that they had not built, provided, dug, or planted. When they would eat and be satisfied, they might “forget” (GK 8894) the Lord who brought them out of Egypt, the land of slavery. The warning was wise, for the people later did exactly what Moses warned against.

13–19 The warnings continue, focused on the necessity of recognizing and obeying their God because of who he is and what he would do if they did not acknowledge and obey him. The people must adhere to him so that it may “go well” with them and so that they may thrust their enemies from the “good land.” If they do not devote themselves to him (“fear” him), worship and work for him only (“serve” him), and speak of him in their daily relationships to one another (“take your oaths in his name”) but instead follow other gods, his “jealous” (GK 7862) anger will destroy them as a nation. Many find the jealousy ascribed to God very difficult to understand because jealousy can be such a vicious sin in human beings, producing much grief and animosity. But one must recognize that the provocations that give rise to the Lord’s anger are most severe. Biblical history shows that such provocations frustrate the love of God until his patience with idolatry ceases to be a virtue. Only then does his jealousy call for redress (cf. 32:16–26).

20–25 The answer to a son’s query, “What is the meaning of the stipulations?” is a historical recounting of the Exodus, the making of the covenant-treaty, and the giving of the legislation for the nation, together with the Lord’s commands to obey and reverence him. The Lord had been active on their behalf in freeing them from Egypt and from the control of Pharaoh by his mighty hand, by miracles that taught lessons, and by wonderful acts that were great and terrible—an appropriate description of the plagues. God had brought them out of Egypt in order to bring them into Canaan, the country that he had promised to their forefathers. Obedience was necessary for their prosperity and continuance as a people in that land. Obedience to all the Lord’s legislation would constitute their “righteousness” (GK 7407; see 24:13). These items must be impressed on each succeeding generation.

3. Problems of achieving the covenant of love in the land (7:1–26)

a. Relations with the people of the land and with the Lord (7:1–10)

1–2 The Hittites mentioned here were remnants of the great Hittite Empire that began about 1800 B.C. and continued to 1200 B.C. Smaller Hittite states existed prior to this and after. The Girgashites were an otherwise unknown group; they are mentioned in Ugaritic literature. The Amorites were situated west of the Jordan near the Canaanites who were on the southwest coast on the Mediterranean (Jos 5:1). Canaanites lived farther north also (Jos 11:3; 13:4).

Apparently the Perizzites lived in the southern area allotted to Judah and Simeon (Jdg 1:4–5). However, they also appear to be in the area of Ephraim in the center of the country (Jos 17:15). At this time the Hivites were found in Gibeon (Jos 9:7; 11:19; cf. 2Sa 24:7). The Jebusites lived in Jerusalem and its surroundings (Jos 18:28; Jdg 1:21).

Israel would win the land from its inhabitants by driving them out and destroying the ones remaining (cf. 7:1, 2 2). The Lord would drive out the Canaanites and “deliver them over to” Israel (vv.2, 16, 23); but the Israelites would be the instrument used to accomplish this destruction—though the Lord might use other persuaders also, such as the hornet (v.20). The inhabitants who were not driven out of the country were to be destroyed. No treaty was to be made with them, no mercy shown to them. The covenant-treaty of the Lord with Israel excludes other treaties.

3–5 The young Canaanite men were not to be given Israelite daughters as wives, and young Canaanite women were not to be taken by Israelite men as wives. This would lead to forsaking the Lord and to worshiping other gods. Only by total commitment to the Lord and to the covenant-treaty could the unique status of Israel be preserved. The prohibition of intermarriage was not absolute. The regulation for the marriage of an Israelite man to a foreign woman taken as a prize of war is given in 21:10–14 (but cf. Ezr 9–10; Ne 13:23–27). “Destroy them totally” and “show them no mercy” (v.2) are explicated more fully by “break down their altars, smash their sacred stones, cut down their Asherah poles and burn their idols in the fire.”

6–10 The Israelites were the Lord’s “treasured possession” (GK 6035; a people of great value owned completely by him). Moses, concerned that Israel keep the right perspective in her relationship with the Lord, pointed out that the large number of people in the Israelite community was not the reason for the Lord’s choice of them as his people. They were few in number (in contrast to the large Near Eastern empires, or even in comparison with the seven nations they were to displace; cf. 4:38; 9:1; 11:23)—or perhaps the reference is to their small beginnings. Elsewhere Israel is said to be “as many as the stars in the sky” (1:10; 10:22) and “a great nation” (4:6; 26:5)—doubtless in fulfillment of the promise to Abraham.

Because he loved them and kept the promise of his covenant, the Lord brought the Israelites out of Egypt. It is the character of God rather than any excellence in the people that accounts for the choice. This is more evident by the reiterated assertion that the Lord their God was God, was faithful and true in himself and true to his covenant-treaty, and would be true in his covenant love toward his people into the distant future—“to a thousand generations of those who love him and keep his commands.” But those who hate him, who do not love and obey him, he will repay with destruction “to their face.” Both the singular suffix on “face” and the figurative use of “face” (GK 7156) suggest the meaning “to each one personally.”

b. Blessing of the conquest (7:11–26)

11–16 If the Israelites followed the Lord’s stipulations, he would keep his “covenant of love” with them (cf. vv.13–15). He would love and bless them with many children and with productivity in crops and animal husbandry. These blessings were of things close to the soil and natural productivity. Good health too would come to the obedient Israelites. Those terrible diseases they knew in Egypt would not come on them (Ex 15:26; 23:25) but would be inflicted on their enemies. To secure these advantages, the Israelites were to destroy without pity the Canaanites and their gods (cf. Ex 23:33; Jdg 2:3; Ps 106:36; cf. also Ex 34:12; Jos 23:13).

17–26 The Israelites were not to be intimidated by thinking that the nations of Canaan were stronger than they, making it impossible for them to drive out the Canaanites. They were to “remember” (GK 2349) what the Lord had done to Pharaoh and all Egypt. With their own eyes they had seen how the Lord had brought them out (cf. 4:34). He would do to the Canaanites what he had done to other enemies. He would also send the “hornet” among them so that even those who survived the onslaught and hid themselves would die (this likely refers to a sense of fear, panic, or discouragement that the Lord would inflict on the Canaanites; cf. 11:25). Moses reminded the people that the great and awesome Lord was among them; so they should not be terrified by the Canaanites. However, their driving out the Canaanites would be little by little because of the wild animals (cf. Ex 23:30–31).

Though the conquest was not to be immediate over the whole land, the Lord, nevertheless, would deliver the Canaanites into Israel’s hand. They would wipe out their kings’ names from under heaven, i.e., remove them from the earth. The destruction of the Canaanite idols was to be complete. Even their silver and gold were detestable to the Lord. “Utterly abhor and detest it” indicates the abhorrence the people were to hold toward the idols.

4. Exhortation not to forget the Lord (8:1–20)

a. The discipline of the desert and the coming Promised Land (8:1–9)

1–5 Moses first focused on the necessity of following every command of the Lord so that Israel would be able to enter and possess the Land of Promise. They were to remember the discipline of the forty years of the Lord’s leading in the desert, in order to teach them that “man does not live on bread alone but on every word that comes from the mouth of the LORD” and that “as a man disciplines his son, so the LORD . . . disciplines” them. He had made them hungry, then fed them with manna (see Ex 16). Under his providence during those forty years, their clothes did not wear out and their feet did not swell, in spite of the desert.

6–9 The Israelites were urged to walk in the ways of the Lord and to revere him, not only as in the past days of hunger and thirst, but also when the affluence of Canaanite productivity became theirs. The country he was leading them into had great natural benefits. This contrasted both with Egypt proper and with Sinai. This good land would sustain them; they would lack nothing. The iron was probably that in southern Lebanon, in the mountains of Transjordan, and, perhaps, in the Arabah south of the Dead Sea.

b. Remembrance of the Lord who led them from Egypt to Canaan (8:10–20)

10–18 When the Israelites had eaten and were satisfied, after they were settled in the land, they were to praise the Lord for his goodness. In their prosperity they were not to forget him. They had lived through the hard life of that desert by God’s providence, but the future prosperity in a better land might lead them astray. In that desert experience the Lord had brought water out of the hard rock (cf. Ex 17:1–7; Nu 20:2–13); in Canaan they would find streams and pools. In that desert the Lord gave them manna. In Canaan bread would not be scarce. In their prosperity they might claim that their hands produced their wealth, not remembering that the Lord their God gave them the ability to produce wealth in confirmation of his covenant.

19–20 Once more Moses warned that forgetting and disobeying the Lord and turning to follow other gods to worship and bow down before them would mean the destruction of Israel as surely as those who followed other gods were destroyed by the Israelites.

5. Warning based on former infidelity (9:1–10:11)

a. The coming defeat of the Anakites (9:1–6)

1–6 Moses recognized the difficulties that the people would face in the country they were about to possess. The current inhabitants were greater and stronger than the Israelites (4:38), with large cities with walls up to the sky (cf. 1:28). But Moses had an adequate answer to the proverbial Anakite strength: The Lord would go across ahead of them (cf. Ex 13:21; Dt 1:30, 33, et al.). Almost in the same breath, Moses said that Israel would drive out the inhabitants and that the Lord would drive them out, indicative again that Israel’s abilities were from the Lord. At best they were the Lord’s instruments.

One of the most important things for the people to remember was that not Israelite righteousness but Canaanite wickedness was causing this Canaanite dispossession (Lev 18:1–30). As a matter of fact, Israel was an intractable people and, consequently, not deserving of the good land. They were receiving it by God’s grace.

b. The golden calf provocation (9:7–21)

7–14 Moses sought to impress strongly on the people that they must not provoke the Lord by disobedience as they began the conquest of Canaan. Continuing his warnings, Moses reminded Israel of their behavior from the time they left Egypt till they arrived at Jordan. He exhorted them to remember how they had rebelled against the Lord, provoking his anger and arousing his wrath. He had been angry enough to slay them at Horeb. Moses had gone up on the mountain to receive the Ten Commandments (Ex 19–20; 31:18). After forty days, the Lord told Moses to go back down to the people who had become corrupt with idolatry. God told Moses that the people were stiff-necked (cf. v.6) and asked Moses not to interfere with his intention to destroy them, offering to make Moses into an even stronger and more numerous nation.

15–17 Moses proceeded to tell how he went down from the fiery mountain, carrying the two stone tablets in his hands, or perhaps one in each hand. When he saw that the people had sinned against the Lord by making an idol, Moses threw down the two tablets, breaking them before the people’s eyes. The nature of their sin is indicated not only by the indictment of making the calf-idol but also by their turning away quickly from the Lord’s commands. The first two commands on the tablets that were physically broken by Moses had already been broken by the people.

18–21 Moses spoke of the second period of forty days and nights and also referred to two prayers on their behalf. Those two prayers are telescoped, a reference to the destruction of the calf-idol being at the end of the narrative. Moses said he feared the anger and wrath of the Lord because he was angry enough to destroy the Israelites (cf. v.8). But Moses’ intercession was successful both for the people and for Aaron. Moses destroyed the calf by heating it, grinding it to fine dust, and throwing the dust into a mountain stream. “That sinful thing of yours, the calf you had made” contrasts with the Lord himself as the Almighty Creator. Exodus 32:20 adds that Moses threw the dust into the stream and “made the Israelites drink” from the stream—surely an ignominious exercise!

c. Israel’s rebellion and Moses’ prayer (9:22–29)

22–24 Repeatedly the people had showed themselves rebellious and stiff-necked, and thus they angered the Lord. So Moses made the overall indictment: “You have been rebellious against the LORD ever since I have known you.” The source of this rebellion was their lack of trust in the Lord and, consequently, their disobedience to him.

25–29 Again Moses mentioned how he had interceded successfully for Israel (cf. Nu 14:13–19). From a most humble position, Moses addressed God as “Sovereign LORD” and prayed eloquently, reminding God that these were his people, his own “inheritance” (GK 5709), and that he had redeemed them from Egypt by his great power and mighty hand. He called on the Lord to remember Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—doubtless a reference to the covenantal promises. If God’s people were destroyed, the Egyptians would indict him for his inability to bring Israel into the land and for his trickery of leading them into the desert to slaughter them (because he hated them). Moses did not at all deny the people’s guilt but pled with the Lord to overlook their stubbornness, wickedness, and sin.

When he spoke to Moses about the people’s sin while he was on Horeb the first time, God called the Israelites “your people whom you brought out of Egypt” (v.12); but when Moses prayed, he said that they were “your people, your (own) inheritance.” Why this change of identification? God was probably trying to evoke Moses’ concern for his people by identifying them as Moses’ people whom Moses had brought from Egypt. Moses did show his concern by his great intercessory prayer in which he insisted that the people belonged to the Lord, and this brought the desired result.

d. New tablets (10:1–11)

1–5 Moses next rehearsed the second experience regarding the two stone tablets of the covenant (Ex 34:1–4). “At that time” refers to the period when Moses offered the prayer of 9:26–29. At the Lord’s command he had chiseled out two stone tablets similar to the first ones. God said that he would write on them the words that had been on the first tablets. Moses was also to construct a wooden chest for the tablets. In deference to tradition NIV uses the term “ark” (GK 778) for this particular chest. Exodus 37:1–9 reveals that the ark was built by Bezalel after Moses’ return, rather than that Moses made it himself before he went up the mount the second time, as could be implied here. It is not uncommon that a leader of a venture is said to do something when the actual physical accomplishment of it is done by someone else.

6–9 The “wells of the Jaakanites” is to be identified with Bene Jaakan, Moserah with Moseroth (Nu 33:31), and Gudgodah (v.7) with Hor Haggidgad (Nu 33:32). It appears that after leaving Kadesh, Israel went toward Edom and then later returned to Kadesh before starting on the last trip around Edom and up onto the plains of Moab. Consequently the order here is the reverse of that in Nu 33:31–33. Moserah was evidently a larger area that included Mount Hor. So it was correct to identify Aaron’s place of death as either Mount Hor (Nu 20:22–29; 33:38–39; Dt 32:50) or Moserah (Dt 10:6). Moserah means “chastisement” and might be Moses’ designation of the area, not a generally used name. None of the places mentioned has been located with certainty.

Verses 6–9 are a historical aside. Moses’ mind moved along the course of events relating to the ark and then proceeded to the Israelites’ journey beginning just before the death of Aaron and includes Aaron’s death, the succession of Eleazer, the ministry of the Levites relative to the ark, as well as their broader ministries and their special situation regarding landed inheritance (GK 5709; cf. 9:29). The Lord himself in a special way—not land—was to be their inheritance.

10–11 The climax of this recital is Moses’ declaration that the Lord listened to his plea on the Israelites’ behalf. It was not the Lord’s will to destroy them. The grace of God—not because they were numerous or righteous—kept them from destruction (cf. 7:7–9), and by his grace Moses’ orders were renewed to “lead the people on their way” to occupy the Promised Land.

6. Exhortation to revere and love the Lord (10:12–11:32)

a. The requirement of allegiance (10:12–22)

12–13 In answer to the question “What does the LORD your God ask of you?” five familiar phrases are piled one on the other. The people are urged to (1) “fear the Lord [their] God”; (2) “walk in all his ways”; (3) “love him”; (4) “serve” him; and (5) “observe [his] commands and decrees.” More or less synonymous with “observe” are the words and phrases “keep,” “obey,” “fix in your hearts and minds,” and “teach his commands, requirements, laws, and decrees.” All this was for their own good.

14–16 Although God, to whom the Israelites were to give their fealty, owns the farthest reaches of the “heavens, the earth and everything in it,” yet he set his affection and love on their forefathers and “chose” (GK 1047) these, their descendants, above all other nations. Because of this gratuitous position they had in relation to the true God, the Israelites were urged to circumcise their hearts and cease being stiff-necked (cf. 30:6; Jer 4:4). The circumcision of the heart—i.e., being open, responsive, and obedient to the Lord—contrasts with being “stiff-necked” (GK 6902 &7997)—i.e., being stubborn and rebellious.

17–22 The majestic sovereignty of the Lord is portrayed by the names ascribed to him as well as by the characteristics and acts attributed to him. “God of gods” and “Lord of lords” are Hebrew superlatives. The designations do not suggest that there are in reality other divine gods or lords over whom God rules. Rather, as God and Lord he is supreme over all. As the great, mighty, and awesome One, the Lord performed the “great and awesome wonders” that the people had seen with their own eyes. The majesty of the Lord extends to righteous behavior, showing no partiality, accepting no bribes. He defends the fatherless and the widows and loves the aliens, giving them food and clothing. The people were to be like the Lord; they too were to love aliens, for they had been aliens in Egypt.

Not only were the people to reverence and worship the Lord, they were also to hold fast to him and make oaths only in his name. Moreover, the Lord was to be the object of their praise because he had brought up out of Egypt the descendants of the seventy (Ge 46:27; Ex 1:5), who, while there, had become “as numerous as the stars in the sky.” In contrast to the few who went down into Egypt with Jacob, this generation had become numerous indeed.

b. Love and obedience toward the Lord (11:1–25)

1–7 The exhortations to love, remember, observe, worship (serve), obey, teach, and walk in the Lord’s ways are all here. The dominant personnel in the nation were those who had seen what the Lord had done for them in Egypt and in the desert. They were not of the generation doomed to die in the desert for their disobedience at Kadesh Barnea (1:35–36) but those who ranged from infancy to the age of twenty (Nu 14:29–30).

Moses focused his attention on those who were the leaders, repeating the exhortation formula: “Love the LORD . . . and keep his requirements.” Then, in a semi-negative way, he built up the responsibility of those who were under twenty years of age at Kadesh Barnea (1:35–36). They themselves had had the experiences in the Exodus and the desert and that should have taught them to love the

Lord and to keep his requirements. Though Korah was a leader of the rebellion described in Nu 16:1–35, he is not mentioned with Dathan and Abiram here. Perhaps Korah is not named because his sons were not destroyed (Nu 26:9–11).

8–15 In order to be able to conquer the land and to live long in it as a nation, the people were to observe the Lord’s commands. The description of the land has a new element. Not only was it “flowing with milk and honey”; it was a land that drank “rain from heaven.” It was not like Egypt, where the planted seed was irrigated by foot because water had to be brought from the Nile. Possibly an Egyptian would use his feet to clear a channel for the flow of water to where he wanted it in his garden. In Egypt water for growing grains, vegetables, and fruits depended on the people’s labors. In Canaan the water came in its season from the heavens by the providence of God; and if the people faithfully obeyed him, he would send the rain.

16–21 However, if the Israelites were enticed to turn away from the Lord and to worship other gods, he would shut the heavens so that it would not rain. Baal (Hadad) did not control the rains that brought fertility to Canaan; rather, it was the Lord who governed the incidence of rainfall. If the people did not worship and obey him, he would shut the heavens (28:23–24; Lev 26:19–20; cf. Mal 3:10).

22–25 The land that the people would acquire by obedience to the Lord under the covenant was limited in two ways: by “every place where you set your foot” and by geographic boundaries. The Lord confirmed this promise to Joshua (Jos 1:3). He also had made a particular promise of this sort to Caleb (1:36), a promise that was fulfilled in Jos 14:9–13. The geographical boundaries are generalized, in harmony with other such promises and prophecies (1:7; Ge 15:18).

c. Directives for the blessing and curse recital (11:26–32)

26–32 The most important addition to the highly repetitive directives of ch. 11 is that of the blessing and curse recital to be proclaimed from Mounts Gerizim and Ebal. The blessing was to be theirs for obedience and the curse for disobedience (cf. 27:9–28:68). The basic element is adherence to the Lord as God, and the basic error is following other gods. No doubt Gerizim and Ebal were chosen because of their centrality and natural adaptability for such an event. They are close to each other and are both about 3,000 feet above sea level. “West of the road” refers to the main north-south road, and “near the great trees of Moreh” indicates a location a little south of the center of the valley between the two mountains.

C. Specific Stipulations of the Covenant-Treaty (12:1–26:19)

1. For worship and ceremony (12:1–16:17)

a. At the place of the Lord’s choosing (12:1–32)

1–14 Chapter 12 presents some crucial elements for the Israelites’ national and individual spiritual lives. (1) The people were to worship the Lord their God in the place he chose to put his Name, the place he identified himself with and where his presence would be manifested (contrast vv.2, 5, 11, 13–14, 26, et al.). (2) The people were not to worship the gods of the Canaanites but were to destroy them, their articles, and their places of worship. (3) Israel was not to worship the Lord in the way or with the means that the inhabitants of Canaan worshiped their gods. (4) Israel’s burnt offerings, sacrifices, tithes, special gifts, vows, freewill offerings, and the firstborn of their flocks and herds were all to be brought to the place in the Promised Land where the Lord chose to put his Name.

“The resting place” (v.8; GK 4957) as a description of the land begins with Jacob’s blessing when he called the allotment of Issachar “his resting place” (Ge 49:15). Psalm 95:11 becomes the source for vital NT teaching; the psalmist says that the Lord had declared of the people who disobeyed him in the desert, “They shall never enter my rest.” According to the author of Hebrews, those who disbelieved, disobeyed, and rebelled did not enter his rest (ch. 3). To fulfill the promise of God, a rest was still to be provided. That rest was for the soul in Jesus as Savior from sin (Heb 4:3). Jesus is the “the resting place” for the believer.

15–28 While sacrificial offerings were to be brought to the central sanctuary, the butchering and eating of meat for regular sustenance could be engaged in anywhere. The only restriction on eating nonsacrificial meat (except for the rules relative to unclean foods) was the prohibition on eating blood (cf. Lev 3:17; 7:26–27; 19:26; and esp. 17:10–14). The blood was to be poured out on the ground like water. The nonsacrificial meat may be eaten by anyone—unclean or not.

The freedom enunciated in v.15 and repeated in vv.20–22 is conditioned by the prohibitions of vv.17–19. The life of the creature is its blood; so the spilling of the lifeblood is the giving of its life as the atoning sacrifice. This central characteristic of the sacrificial system in the OT becomes all important in the NT, where the typical aspects of the OT sacrifices are fulfilled in Christ by the shedding of his blood on the cross as atonement for sin (Ac 20:28; Ro 3:25; Eph 1:7; Heb 9:11–28; et al.)

Tithes, vows, and certain offerings were to be eaten only in the place the Lord chose. Notice that “you, your sons and daughters, your menservants and maidservants, and the Levites” fall under the prohibition.

29–32 The Israelites were to resist the influences of the Canaanite culture and were not to conform to Canaanite religious practices. Death was the penalty for anyone who sacrificed a child by passing him through the fire (Lev 18:21; 20:2–5). This section on the place of worship ends with Moses’ warning neither to add to nor to subtract from all that he had said (cf. 4:2; Pr 30:6; Rev 22:18–19).

b. Worship of other gods forbidden (13:1–18)

1–5 In order to hinder and thwart rebellion against the Lord and adherence to the deities of the country that they were soon to enter, Moses gave the Israelites directions on how to deal with insurrectionists from the Lord’s authority. Dreams were used in prophecy both legitimately (Nu 12:6) and illegitimately Qer 23:25). Moses said that illegitimate prophets were used by the Lord to test the people’s love for him. They were not to be followed (cf. v.4) but were to be put to death so that the evil would be purged from among the people. This test of the prophet overrides all others. The sine qua non of life is total love, commitment, and allegiance to the Lord. Elsewhere the fulfillment of prophecy establishes a prophet as a prophet. In such a case, however, the one who claims to be a prophet does so in the name of the Lord (18:19–22; Jer 28:9).

6–11 Not only rebellious prophets, but one’s closest relatives or friends who said, “Let us go and worship other gods,” were to be put to death, whether the enticement had been made secretly or openly. Moses spoke of the gods of the people who would be around the Israelites as “gods you have not known” or as “gods that neither you nor your fathers have known.” Neither the Israelites nor their fathers had ever acknowledged them as gods. They were not to yield to, listen to, show pity to, spare, or shield an enticer. Not only was the defector to be stoned to death, but the first stone was to be thrown by the near relative or friend that the defector had attempted to drive from the Lord. This extreme punishment was expected to produce good results. Clearly punishment—especially capital punishment—is a deterrent to crime.

12–18 Towns that defected to other gods were to be punished also. Allegations were to be investigated thoroughly and proven before a town was destroyed. Inhabitants, livestock, and all plunder were to be a whole burnt offering to the Lord, and the town was never to be rebuilt. This doom indicates how serious the Lord considered any defection from him. In other circumstances some alleviation of these rigorous rules for destruction was allowed, but under these circumstances no “condemned things” could be salvaged. If Israel kept the Lord’s commands and did what was right in his eyes, he would have compassion on them.

c. Clean and unclean foods (14:1–21)

1–2 Earlier, Moses had referred to the Lord as Israel’s father and to Israel as his son (1:31; 8:5). He had also said that they were holy to the Lord and were his treasured possession (4:20; 7:6). Now, on the basis of this relationship, they were commanded not to follow the ways of mourning for the dead that the nations of Canaan practiced (Lev 19:27–28; 1Ki 18:28).