INTRODUCTION

1. Title

The English title of this book reflects the MT (“judges”), the LXX (“judges”), and the Vulgate (“Book of Judges”) titles. God brought these “judges” to deliver Israel from oppression. Although they were divinely empowered leaders, they did not become hereditary rulers.

Eight men in this book are said specifically to have “judged” or “led Israel” (GK 9149; 3:10; 10:2–3; 12:7, 8–9, 11, 13–14; 15:20; 16:31). Even though others, such as Ehud (3:12–30) and Gideon (6:1–8:32), were judges, it is not specifically said that they “judged” or “led” Israel. Also “leading” Israel was one woman, Deborah (4:4–5). Elsewhere in Scripture the leaders of the period from Joshua’s death to King Saul are also called “judges” (Ru 1:1; 2Sa 7:11). Eli and Samuel were the last two judges. In all there were fifteen judges, if Barak is considered a co-judge with Deborah and if Eli and Samuel are added to the thirteen judges in the book of Judges.

2. Historical Background

The book of Judges covers the period from the death of Joshua to the dawn of the monarchy. Political and religious turmoil accompanied Israel’s attempts to occupy the land that had been conquered and divided by lot under the leadership of Joshua. Apart from the struggle against the Canaanites at the time of Deborah, Israel’s adversaries came from outside the land. Most of these, such as Moab, Midian, and Ammon, were content periodically to plunder the land. The Philistines, however, who at this time entered Palestine in greater numbers, contested with Israel for permanent possession of the land.

Tragically, the Israelites even fought among themselves. Ephraim was ravaged by Manasseh (ch. 12), and Benjamin was almost annihilated by the other tribes (chs. 20–21). Between the days of Joshua and Samuel, Israel plummeted to moral and spiritual disaster. Over and over the pattern of sin followed by oppression was repeated. Occasionally God raised up a Deborah or a Gideon to turn the people back to himself, but the intervals of revival were all too brief.

The events narrated in Judges cover a period of 410 years if viewed consecutively. Such a lengthy time does not, however, fit any accepted chronology of the early history of Israel. Consequently some of the judge-ships must have overlapped. Samson and Jephthah, for example, may have ruled simultaneously—one in the west (in Canaan), the other in the east (in Transjordan; 10:7). Most of the data can be worked into a satisfactory historical framework if we adopt the early date of the Exodus (c. 1446 B.C.) and Conquest (which began forty years later).

3. Authorship and Date

The writer of the book of Judges is unknown. Although he may have been an associate of Samuel, unlike Samuel he did not focus attention on the dangers inherent in the monarchy. The book is a unified whole, divided into three parts: (1) the success and failure of the Israelites in Canaan (1:1–2:5); (2) the period of the judges’ rule (2:6–16:31); and (3) two stories denoting sin and corruption (17:1–21:25).

Several factors show that the author lived and wrote during the early monarchy (c. 1030 B.C.). The hectic events in this book are viewed from the perspective of a united, stable rule: “In those days Israel had not king; everyone did as he saw fit” (21:25; cf. 18:1; 19:1). This statement suits the time of the united kingdom best; and 1:21 points to a period before David’s capture of Jerusalem, for the Jebusites were living there “to this day.” The mention of Canaanite control of Gezer (1:29) implies that the king of Egypt had not yet captured the city and given it to King Solomon as a dowry for his Egyptian bride (c. 970 B.C.).

4. Purpose

The primary purpose of the book of Judges is to show that Israel’s spiritual condition determined its political and material situation. When the Israelites disregarded Joshua’s warnings and worshiped the gods of Canaan, they felt the wrath of an angry God, who allowed the nation to come under the control of tyrants and invaders. Few books of the Bible show human depravity as does this one. When in the midst of their suffering the nation repented of their sin, cried to God for mercy, and turned to him in renewed obedience, God graciously sent deliverers to rescue the people from oppression.

This book also shows that Israel failed to realize her divinely intended goal without a king. The Israelites were unable to govern themselves according to the law of Moses and thereby proved that they needed a king. To this author, monarchy was definitely better than anarchy. The implication is that a nation led by a godly king would experience prosperity under the blessing of God.

The events recorded in Judges also serve in general to fill the gap between the time of Joshua and that of Samuel.

5. Special Problems

One problem that perplexes the reader of Judges is the apparent approval of cruelty and gruesome killing. But such actions as performed by Ehud and Jael are not necessarily sanctioned either by the author or by the Lord. Long neglect of the Mosaic law had left the Israelites with many mistaken notions about God’s will.

Another problem closely related to the above is how God’s Spirit could use men like Jephthah and Samson, whose motives and behavior were open to such serious question. That God worked through Samson need not denote his approval of an immoral lifestyle. In God’s sovereignty the Holy Spirit came on people for particular tasks, and this enduing was not necessarily proportionate to one’s spirituality. The Spirit’s power enabled people to inspire Israel (6:34; 11:29) and to perform great feats of strength (14:6, 19; 15:14). But it was a temporary enduement, and Samson and later Saul tragically discovered that the Lord had left them. The NT experience of the permanent indwelling of the Holy Spirit was not known in the OT.

EXPOSITION

I. The Success and Failure of the Tribes in Canaan (1:1–2:5)

A. The Capture of Adoni-Bezek (1:1–7)

1–2 The first chapter presents supplementary material on the conquest of Canaan viewed from the standpoint of individual tribes. Most of the episodes occurred after the death of Joshua. Before conducting further military action, the people consulted the Lord, probably through the Urim and Thummim handled by the high priest (Nu 27:21). As in the order of march in the desert (Nu 2:9), Judah was designated to be first (cf. also Jdg 20:18). Judah was also the tribe leading the march against Benjamin in the civil war at the end of the book (20:18). Though the Joseph tribes (Ephraim and Manasseh) received the birthright (1Ch 5:1), Judah had been destined to lead the nation (Ge 49:10).

“Canaanites” applies to all the peoples found in the land of Palestine, but at times it is restricted to the inhabitants of the valleys and coastal plains (Nu 13:29). God’s promise that he had “given the land into [Judah’s] hands” parallels his encouraging words to Joshua after the death of Moses (Jos 1:3).

3 Judah invited their full-brother tribe Simeon to join them, especially since Simeon’s territory was surrounded by Judah’s (Jos 19:1) and that tribe was undoubtedly gradually absorbed into Judah. The tribe of Simeon was greatly reduced in numbers during the wilderness wanderings, probably as punishment for their sins of idolatry and fornication in Moab (Nu 25:1–14).

4–5 The Lord fulfilled his promise to Judah, who won a great victory at Bezek (cf. 1Sa 11:8). Adoni-Bezek means “lord of Bezek” (cf. Jos 10:1–3). Adoni-Bezek died in Jerusalem (v.7).

6–7 The severing of Adoni-Bezek’s thumbs and big toes incapacitated him as a warrior and as a priest, a dual function common to many kings. In their ordination service the priests had blood applied to their thumbs and big toes (Lev 8:23–24). Adoni-Bezek admitted that he had similarly mutilated the thumbs and toes of seventy rulers of cities, making beggars out of them; so he deserved to be paid back (cf. Ex 21:24).

B. The Capture of Jerusalem, Hebron, and Debir (1:8–15)

8 The city of Jerusalem did not become an integral part of Israel until David stormed the fortress of the Jebusites (2Sa 5:7). Hence the successful attack of Judah was either a temporary or partial capture.

9 From Jerusalem the men of Judah went south and west to continue their conquest. The three areas mentioned are the major geographical divisions of southern Palestine. The “hill country” is the central mountainous region, the “Negev” is the dry ground in the southern part, and the “western foot-hills” represent the region between the mountains and the coastal plain.

10 Hebron (some nineteen miles south of Jerusalem) has the highest elevation (3,000 ft.) of any city in Judah and is famous as the home of Abraham (Ge 13:2; 23:2, 19). Sheshai, Ahiman, and Talmai were descendants of Anak, who had terrified the spies (cf. Nu 13:22–33). This time, however, the men of Judah conquered them. Fittingly, Caleb, one of the two believing spies, was allotted Hebron as his inheritance (Jos 14:13–14); he directed its capture (Jdg 1:20; see also Jos 15:13–19).

11–13 Debir is located eleven miles southwest of Hebron. Its king was listed among the thirty-one kings captured by Joshua (Jos 12:13). Like Hebron it was a residence of some Anakites (Jos 11:21). This city was captured by Caleb’s younger brother Othniel after Caleb offered his daughter Acsah as the prize. Normally young men paid a bride-price to the father of the bride, but the military triumph was considered payment enough (cf. 1Sam 18:25). As relatives of Kenaz, Othniel and Caleb were apparently associated with an Edomite clan (Ge 36:11). Their rise to prominence in Judah and Israel demonstrates the degree to which other people were assimilated by the chosen nation.

14–15 Caleb’s daughter needed the permission of her husband before she could ask her father for a gift. Since Caleb had given them land in the arid Negev, she requested a field with “springs of water.” Caleb agreed, and this gift may have been her dowry.

C. The Additional Success of Judah and Simeon (1:16–18)

16 The Kenites, an ancient Canaanite people (Ge 15:19) connected with the Amalekites, had been friendly to Israel during the wilderness wanderings. Moses had, in fact, married a Kenite girl. The Kenites left Jericho, the “City of Palms” (3:13), and joined some people of Judah living near Arad, an important city sixteen miles directly south of Hebron. Moses had defeated the king of Arad as Israel skirted southern Palestine (Nu 21:1–3), and Joshua later counted Arad’s king among his victims (Jos 12:14).

17 Judah together with Simeon successfully captured Zephath, renaming it Hormah—a city that was allotted to Simeon (Jos 19:4). Since the name means “total destruction,” it may be the same Hormah demolished by Moses near Arad (Nu 21:1–3). The complete destruction recalls the Lord’s command to wipe out the Canaanites and their livestock and give all the articles of silver and gold to the sanctuary (Dt 7:1–2; 20:16–17; Jos 6:17–19).

18 The capture of Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ekron by Judah must have been temporary (cf. v.19). These were Philistine cities along the coast, though the main migration of the Philistines did not reach Palestine until 1200 B.C. The order of the three cities suggests an invasion from the south.

D. A Summary of Success and Failure (1:19–21)

19 While notably successful in the hilly regions of central Palestine, Judah failed to control the plains. The Israelites were no match for the iron chariots that functioned effectively on the level terrain along the coast (see especially chs. 4–5).

20 Taking Hebron represented the key achievement of Judah, and v.20 attributes its capture to Caleb (cf. also v.9). Hebron became a city of refuge belonging to the priests (Jos 20:7; 21:11), but its fields and suburbs were Caleb’s own possession (Jos 21:12).

21 Benjamin’s main city was Jerusalem, but neither Benjamin nor Judah could dislodge the Jebusites (see comment on v.8). An alternate name for Jerusalem is “Jebus” (19:10), which attests to the long attachment of the Jebusites to this natural stronghold.

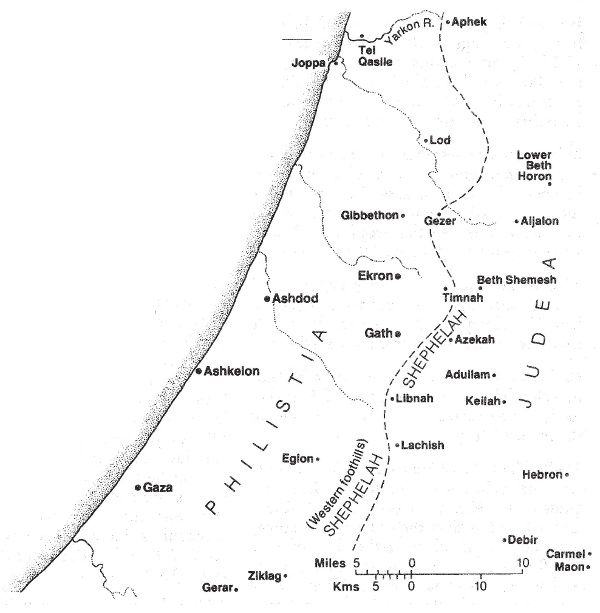

Five Cities of the Philistines

Like a string of opulent pearls along the Mediterranean coast, the five cities of the Philistines comprise a litany of familiar Biblical names: Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron and Gath.

Each was a commercial emporium with important connections reaching as far as Egypt along the coastal route, the “interstate highway” of the ancient world. The ships of Phoenicia, Cyprus, Crete and the Aegean called at Philistia’s seaports, which included a site today called Tell Qasile, where a Philistine temple has been found, on the Yarkon River just north of modern Tel Aviv.

The Philistine plain itself was an arid, loess-covered lowland bordering on the desert to the south—a stretch of undulating sand dunes adjacent to the sea—and the foothills of the Judahite plateau on the east. No area in Biblical history was more frequently contested than the western foothills (the Shephelah region), lying on the border between Judea and Philistia. Beth Shemesh, Timnah, Azekah and Ziklag were among the towns coveted by both Israelites and Philistines, and they figure in the stories of Samson, Goliath and David.

The area to the north of Philistia, the plain of Sharon, was also contested at various periods: During Saul’s reign the Philistines even held Beth Shan and the Esdraelon valley. Later, from about the time of Baasha on, a long border war was conducted by the Israelites at Gibbethon. Originally a part of Judah’s tribal allotment, the coastal area was never totally wrested away from the Philistines who may have begun their occupation as early as the time of Abraham.

E. The Capture of Bethel (1:22–26)

22 Next to Judah, the most important tribe was Ephraim; and vv.22–29 describe the activities of Ephraim and his brother, Manasseh. The two tribes may have cooperated in the capture of Bethel (about twelve miles north of Jerusalem), since the attack is attributed to “the house of Joseph”; but the city lay within Ephraim’s territory. Bethel means “house of God,” a name given by Jacob after God’s revelation to him there (Ge 28:19). As God promised to protect the patriarch, so he “was with” the Joseph tribes here. Bethel was to become a key religious center during the divided kingdom.

23–25 To capture Bethel, Israel followed the strategy used at Jericho. Spies were sent there, and they found a man willing to show them the entrance to the city. In return for his cooperation, the spies promised safety for the informer, just as Rahab and her family had been protected at Jericho. When the Israelites captured the city, they released the man and his family.

26 These survivors headed north, “to the land of the Hittites,” a term applied to Syria (Jos 1:4). The Hittite Empire was based in Asia Minor but extended its control over wide areas west of the Euphrates.

F. Additional Failures of the Tribes (1:27–36)

27 The remainder of ch. 1 records the inability of the other tribes to occupy territory. Manasseh’s allotment included several key cities in the Valley of Jezreel. Joshua 17:16 mentions the problems in this area because the Canaanites had “iron chariots.” Beth Shan was an important fortress controlling a trading route across the Jordan.

Taanach was five miles southeast of Megiddo, a city that controlled the pass at the entrance to the Jezreel Valley. Dor lies along the Mediterranean coast south of Carmel; Ibleam is situated at the southern end of the Jezreel Valley near Dothan. Joshua had defeated the kings of these three cities (Jos 12:21, 23), but a permanent Israelite occupation did not follow. The Canaanites, like the Amorites in vv.34–35, were determined to keep their living areas and resist Israel.

28 The most the Israelites could do was to exploit the Canaanites as a cheap labor force. Moses earlier had instructed the nation to use the residents of peaceful cities near Canaan as forced laborers, but the peoples of Canaan were to be totally destroyed (Dt 20:11–17).

29 Ephraim failed to gain possession of Gezer, a city eighteen miles west of Jerusalem. This city guarded the approaches to the foothills and Jerusalem from the northwest.

30 Zebulun’s territory was north of Manasseh’s. The cities of Kitron and Nahahol likely were situated on the northern edge of the Jezreel Valley.

31–32 The tribe of Asher experienced wide setbacks against Acco, Aczib, and Sidon, regions on the Mediterranean north of Mount Carmel, and against the other towns somewhat farther inland. Here the cities of Tyre and Sidon led a strong Canaanite culture with its vigorous Baal worship. Their culture and religion had a strong influence on Israel, especially during the reigns of Solomon and Ahab.

33 The Naphtalites, whose region lay to the east of Asher, failed to dislodge the residents of Beth Shemesh and Beth Anath. Beth Shemesh (“house of the sun”) may have had a sanctuary devoted to the worship of the sun god; Beth Anath contains the name of Anath, the Canaanite goddess of war and both consort and sister of Baal.

34–36 The fortunes of the tribe of Dan have a certain prominence in Judges (see ch. 18). Their difficulties stemmed from Amorite pressure to keep them out of the plains and valleys, where most of their inheritance lay. The Amorites kept control of Aijalon, eleven miles northwest of Jerusalem, and nearby Shaalbim. After the Danites migrated north, the nearby tribe of Ephraim finally subjugated the Amorites. The “Scorpion Pass” is located south of the Dead Sea, at the southern border of the Promised Land (Jos 15:2–3).

G. Disobedience Condemned by the Angel of the Lord (2:1–5)

1–2 The deplorable spiritual condition of the Israelites lay behind their failure to dispossess the Canaanites. To expose Israel’s sinfulness, the “angel of the LORD” appeared to them. This angel, frequently identified with God himself (6:2; 13:21–22), was perhaps a preincarnate form of the Second Person of the Trinity. His announcements to Gideon and to Samson’s parents promised deliverance at crucial points in Israel’s history. The move from Gilgal to Bokim may signify the relocation of the tabernacle. Gilgal, situated between the Jordan and Jericho, had been the initial religious center (Jos 4:19–20). In 20:18–28 and 21:1–4, Bethel is identified with the sanctuary.

The angel of the Lord charged Israel with breaking their covenant with God in spite of his faithfulness on their behalf. God had fulfilled his promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He would “never break [his] covenant” (cf. Lev 26:42–44; Dt 7:9); and out of gratefulness Israel was expected to obey him. Yet they entered into agreements with the Canaanites, including marriage covenants (cf. Pr 2:16–17), and did not tear down their altars (Ex 34:12–13).

3 God therefore did not help the Israelites drive out their enemies but left some to trap them through pagan customs and religions. Israel had been repeatedly warned that the Canaanites could become irritants in their eyes and thorns in their sides (Nu 33:55; Jos 23:13).

4–5 The response of the people to the angel’s sad pronouncement was to weep loudly. Like the weeping of Nu 14:1, when the spies announced that Canaan could not be captured, here the crying does not necessarily imply repentance. They offered sacrifices, however; and the burnt offerings and fellowship offerings sacrificed at Bethel not long after (21:1–4) did connote national mourning. “Bokim” means “weeping.”

II. The Rule of the Judges (2:6–16:31)

A. Introduction (2:6–3:6)

1. The passing of godly leaders (2:6–9)

After the summary of the incomplete wars of occupation, we meet the threatening wars of liberation that characterize the period of the judges. To explain how Israel fell prey to powerful oppressors, the author reviews events since the death of Joshua.

6–9 Just before his death, Joshua had led the people in renewing the covenant with the Lord (Jos 24). Then he sent them away to finish occupying the land. What they did about this is described in ch. 1. Joshua was buried on the land allotted to his family in Timnath Heres. He received the exalted title of “servant of the LORD” (see comment on Jos 24:29). During the lifetime of Joshua and the leaders who outlived him, Israel was relatively faithful to the Lord. These men had experienced God’s miracles.

2. The pattern of the period of the judges (2:10–23)

10 After the death of Joshua’s contemporaries, the new generation accelerated down the highway to destruction. They did not know God in a vital way nor had they seen the miracles their fathers had talked about. Each generation must personally experience the reality of God.

11–13 History repeated itself as Israel went through the fivefold pattern of sin, slavery, supplication, salvation, and silence. The sin phase is always introduced with the words “The Israelites did evil in the eyes of the LORD” (3:7, 12; 4:1; 6:1; 10:6; 13:1). They deserted the very God who had delivered them from Egypt and had saved them from Pharaoh and his host (cf. v.1). They worshiped Baal—an epithet of the Canaanite storm god Hadad, the god of rain and agriculture, and the leading deity in the pantheon. There were also “Baals” associated with particular places (see Nu 25:3; Jdg 9:4). Israel’s earlier encounter with the Baal of Peor had been disastrous (Nu 25). The “Ashtoreths” were deities such as Astarte, who was goddess of the evening star and renowned for her beauty. She was a goddess of fertility, love, and war, and was often linked with Baal (10:6).

14–15 The Lord became angry at Israel’s apostasy and turned the Israelites over to their enemies, thus initiating the slavery phase of the cycle. God “sold them” as one sells a slave (3:8; Dt 32:30). Israel’s crops, supposedly guaranteed by the worship of Baal, were carried off year after year. The strong hand of the Lord now acted to secure Israel’s defeat (cf. Dt 28:25). In their distress the people entered the supplication stage; they cried out to the Lord.

16–19 Salvation came through the judges raised up by God. Some fifteen individuals could claim this designation, though six are “minor” judges who are mentioned only briefly (Shamgar, Tola, Jair, Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon). Not long after gaining Israel’s freedom, the people forgot what the Lord had done (the silence stage), and the judges would find them newly enmeshed in sin. Their religious prostitution meant that they were forsaking the nation’s true “husband,” the Lord (“Baal” means “husband” or “owner”). Moreover, the worship of the Canaanite gods literally involved sexual conduct with temple prostitutes supposedly to promote the fertility of the soil.

The Lord spared the people throughout the lifetime of a given judge, even though they deserved to be resubjugated. The words “groaned” and “oppressed” (v.18) relate back to the Egyptian bondage (cf. Ex 2:24; 6:5; 3:9). Then after the death of a judge, the corruption of the people increased; they became “stubborn” (GK 7997), repeating their stiff-necked attitude in the desert (cf. Ex 32:9; 33:3, 5).

20–23 Again the anger of the Lord is mentioned (cf. vv.12, 14). There is a note of contempt as the Lord addressed the people as “this nation” rather than as “my nation” (cf. Hag 1:2). The summary here closely resembles the stern pronouncement of vv.1–3 by the angel of the Lord. Violating the covenant meant a slower conquest of Canaan. The nations would be left there to test Israel’s desire to obey the Lord. The constant pressure from a pagan culture would prove who the genuine believers really were.

3. The people left to test Israel (3:1–6)

1–2 The nations left in Canaan to test Israel had another purpose: they afforded practical experience in warfare, for these new generations of Israelites had not participated in Joshua’s wars of occupation. Israel would one day confront major powers like Egypt and Assyria; so the smaller wars provided valuable training. Part of God’s sovereign action was to use the Canaanites both to punish and to teach Israel.

3–4 The Philistines (who had migrated from Caphtor of the Aegean area) are mentioned first, perhaps because they were to become the primary opponents of Israel. Their five-city cluster along the Mediterranean included Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gath, and Ekron. The “Sidonians” refers to the Phoenicians, whose leading port city was Sidon (cf. 1:31). The Hivites were located in northern Israel in Jos 11:3, but Shechem (cf. Ge 34:2) and Gibeon (Jos 9:3, 7) in central Palestine were also Hivite cities.

5–6 The Hittites may not be the same north Syrians of 1:26 but another Canaanite people well known at Hebron in the hills of Judah (Ge 23). Intermarriage with the peoples of Canaan had been forbidden (Jos 23:12) since it would lead directly to idolatry. It was into that very trap, however, that the nation fell (cf. 2:1–3).

B. The Victory of Othniel Over Cushan-Rishathaim (3:7–11)

7 The first cycle, though brief, follows the pattern delineated in ch. 2. Israel sinned by forgetting God and worshiping foreign deities. “Asherah” was the wife of both El and Baal, and some confuse her with Ashtareth/Astarte (2:13). An “Asherah” was also a symbol of the goddess, a sacred tree (Dt 16:21), or a carved pole set up beside an altar to Baal (Jdg 6:25).

8 Israel’s sin angered the Lord, who sent Cushan-Rishathaim, king of Upper Mesopotamia, to oppress them. The king’s name seems to mean “Cushan of double evil,” a rather strange designation but perhaps intended to be an intimidating one. “Cush” (Ge 10:8) was the father of Nimrod, founder of Babylonian civilization.

9–10 When the Israelites appealed to God for help, Othniel was commissioned to rescue them. This relative of the illustrious Caleb has already been introduced in 1:11–15 as a successful warrior. His selection shows that the oppression followed Joshua’s death quite closely, perhaps about 1375–1367 B.C. When the Spirit of the Lord came on him, Othniel won a great victory. The empowering of the Spirit is crucial in Judges, and down to the time of David it remained the mark of God’s chosen vessel.

11 Othniel’s triumph ushered in a forty-year peace, the first of several peace periods given in multiples of forty (v.30; 5:31; 8:28).

C. The Victory of Ehud Over Moab (3:12–30)

1. Israel oppressed by Moab (3:12–14)

12–14 When Israel again fell into sin, God used their perennial enemy Moab to subdue them. Usually the Lord gave strength to the Israelites (e.g., 16:28), but here the Lord was on the side of Israel’s foe. In Moses’ day the Moabites had attempted to thwart Israel by hiring Balaam to curse them, and along with the Midianites they had actually involved God’s people in idolatry (Nu 25). Now Moab had allies such as the Amalekites, who had bitterly opposed Israel in the desert (Ex 17:8–16).

Moabite forces crossed the Jordan and occupied Jericho (“City of Palms”). This means that they had first defeated the tribe of Reuben, which had inherited territory east of the Dead Sea. Because of their locale, the Transjordanian tribes were especially vulnerable to enemy attack. Jericho had been cursed by Joshua (Jos 6:26) and was probably unoccupied when King Eglon moved in. From this strategic base Eglon dominated the Israelites for eighteen years.

2. King Eglon slain by Ehud (3:15–25)

15 God’s choice to end the Moabite oppression was a man from Benjamin. Ehud was a left-handed man of the same mold as the seven-hundred expert slingers from Benjamin who fought in the civil war (see 20:13b–16, 43–47).

16–17 Ehud’s task was ostensibly to make the yearly tribute payment to Eglon to assure him of Israel’s subjection for another year. Since the payment was carried by a number of men, it may have been food or wool. For the occasion Ehud had made a small sword or dagger, about eighteen inches long. It was well concealed, and the fact that he was left-handed enhanced his stratagem.

18–23 Apparently Ehud and his men left Jericho before Ehud returned alone to strike his fatal blow. “The idols near Gilgal” were most likely a well-known landmark. After the other Israelites were safely en route home, Ehud came back to seek a private audience with Eglon. The king wanted to hear this secret message, so he requested his officials and attendants to leave. With Eglon sitting in the cool upper room of his palace, Ehud presented the “message from God.” The king stood up reverently to hear the divine oracle, and Ehud drew his sword and delivered the fatal “message.” Perhaps the huge size of the king (cf. v.17) and the unexpected use of the left hand prevented him from seeing Ehud’s move, for it is clear that no cry of alarm was heard outside. Ehud left the dagger completely buried in Eglon’s abdomen and made his escape, locking the doors of the room to prevent quick detection of his crime.

24–25 Eglon’s officials hesitated to unlock the doors, assuming that their master might be seeing to his bodily needs. Finally they became suspicious and took a key to remove the bolt from the doors. They found the king lying on the floor, the victim of assassination. God did not necessarily approve of the method used by Ehud, for the Spirit of the Lord did not come on Ehud, and he was never described as “judging Israel” (cf. 2Sa 4:11).

3. The Moabites defeated by Ehud (3:26–30)

26 The reluctance of the Moabite officials to break into the king’s room gave Ehud the time he needed to escape. He followed the same route he had started to take earlier (cf. v.19), heading for the unidentified “Seirah.” His goal was to reach the hill country of Ephraim. Ephraim was one of the most powerful tribes of Israel and occupied the territory adjacent to Benjamin on the north.

27–29 Ehud knew that the death of Moab’s king would throw the officials and troops at Jericho into confusion—an opportune time to strike the hated invaders and end their rule. Using the ancient alarm system of a trumpet (Nu 10:9), Ehud quickly assembled Israelite men to help him follow up his personal triumph. Ehud’s bravery and enthusiasm inspired a large following, for all sensed that the Lord was handing the enemy over to them. Under Ehud’s command the Israelites took control of the fords of the Jordan and cut off Moab’s line of retreat (cf. 7:24; 12:5–6). Ehud led the rout of ten thousand Moabites, who probably represented Eglon’s crack troops.

30 Israel’s victory restored her independence as Moab was “made subject” (GK 6268) or “subdued.” This verb is used at the end of several cycles in Judges (4:23; 8:28; 11:33) to indicate a thorough defeat. Eighty years of peace (1309–1229?), the longest “rest” in the book, followed Ehud’s triumph.

D. The Victory of Shamgar Over the Philistines (3:31)

31 The reference to Shamgar is brief but intriguing. As with some of the other minor judges, there is no mention of the sin of Israel (10:1–5; 12:8–15). Shamgar’s work was explicitly military. He won an astonishing victory over the Philistines by means of an oxgoad (cf. 15:16)—a stout stick tipped with bronze and used for prodding animals. Shamgar’s use of this weapon implies that the Philistines were already disarming neighboring people (cf. 5:8; 1Sa 13:19–22).

Shamgar is a foreign name. His name is mentioned in 5:6, along with Jael, as a hero of Israel. He may have been a contemporary of Ehud, since the latter’s death is not cited till 4:1.

E. The Victory of Deborah and Barak Over Jabin and Sisera (4:1–5:31)

1. The prose account (4:1–24)

Somewhat in the form of Hebrew parallelism, Judges has two supplementary accounts of the victory over the Canaanites. The first is in narrative fashion; the second is a majestic poem.

a. The oppression (4:1–3)

1–3 The next major oppression came at the hands of a coalition of Canaanite forces led by Jabin and Sisera, and it affected primarily the northern tribes. Jabin lived in Hazor, once the largest city in Palestine, some nine miles north of the Sea of Galilee on the main route between Egypt and Mesopotamia. Joshua had defeated a Jabin king of Hazor (cf. Jos 11:1–11). Sisera’s strength lay in his 900 chariots, a sizable force for this early period. With this military advantage, he terrorized the tribes living near the Valley of Jezreel.

b. Deborah’s challenge to Barak (4:4–10)

4–5 Deborah was a prophetess, like Miriam (Ex 15:20) and Huldah (2Ki 22:14), and also a judge. Because the rule of women was not normal in Israel, her prominence implies a lack of qualified men. Deborah sat as judge at the southern end of Ephraim’s territory. The reference to a palm tree may allude to the stateliness and gracefulness of women (SS 7:7–8).

6 The Lord commanded Deborah to challenge Barak of Naphtali to confront Sisera’s troops, whose oppression was felt even in Ephraim and Benjamin. Naphtali and Zebulun, the first tribes to be summoned, covered most of Israel’s territory north of the Jezreel Valley. Cone-shaped Mount Tabor rises some thirteen hundred feet from the valley and afforded an unmistakable meeting place. Barak was told to “lead the way”; if he did so, God would lead the enemy into the trap.

7 Deborah revealed that the site of the battle would be near the Kishon River. This river flowed in a northwesterly direction through the Valley of Jezreel and emptied into the Mediterranean north of Carmel. During the summer months it dwindled to a mere stream. The surrounding valley was excellent terrain for deploying chariots. During the spring, however, the rains caused the river to overflow its banks and flood the low-lying areas nearby.

8–10 Barak expressed his willingness to go, but only if Deborah accompanied him. Her presence as a prophetess would assure contact with the Lord, just as the presence of Moses and the ark of the covenant brought victory in battle (Nu 10:35), while their absence meant defeat (Nu 14:44). Barak’s lack of faith prompted Deborah to predict that the honor of killing Sisera would belong to a woman (see v.11). So Deborah went along, and her support helped Barak raise the necessary troops. They began the search for troops in Kedesh, Barak’s hometown.

c. Jael’s husband introduced (4:11)

11 This seemingly intrusive verse acquaints the reader with the family of the woman Deborah had just alluded to in v.9. Jael, the wife of Heber, belonged to the nomadic Kenites, most of whom lived in the arid regions of southern Judah (1:16). As relatives of Moses, this people had a strong tie with Israel. The “great tree" in Zaanannim (cf. Jos 19:33) lay on the escape route taken by Sisera after the battle.

d. Sisera’s army routed by Barak (4:12–16)

12–14 When Sisera learned of Israel’s troop movements at the northeastern end of the valley, he called out his entire chariot force and a large army to advance against them from the west. The presence of a sizable enemy force at Mount Tabor cut off the line of communication between Sisera and King Jabin in Hazor. Humanly speaking Barak’s hastily gathered army had no chance against such might, but Deborah said that this was the opportune moment. She encouraged Barak by announcing that “the LORD [had] gone ahead [GK 4200 & 7156] of [him].” This is a technical term used of a king marching at the head of his army (1Sa 8:20). The Lord would take the lead in striking down the enemy (2Sa 5:24).

15–16 The Lord’s role is even clearer as he “routed” (GK 2169; cf. Ex 14:24; 1Sa 7:10) Sisera’s army. This routing probably took place by a rainstorm (cf. “thunder” in 1Sa 7:10; cf. also Jos 10:10–11), for Deborah’s song shows that a sudden downpour overwhelmed Sisera’s chariots (5:20–21). Even Sisera was forced to abandon his useless chariot and flee north, away from the heated action. The main conflict took place at Taanach, some five miles south of Megiddo (5:19).

The Lord’s control of the forces of nature showed his superiority over Baal, the Canaanite storm god. Sisera would certainly not have tried to depend on chariots during the rainy season; so this storm probably struck some time after the spring rains that normally end in May. The lightly armed Israelites quickly demoralized the bogged-down Canaanites, who turned and fled westward. It was a decisive victory, for the Canaanites never again formed a coalition against Israel.

e. Sisera slain by Jael (4:17–24)

17 Sisera headed north away from the main line of pursuit. He may have hoped to reach Hazor, but his strength was running out. When he arrived at Zaanannim, he decided to take advantage of the hospitality of the friendly Kenites. He knew of their cordial relationship with Jabin but was clearly unaware of their intermarriage with Israel (v.11).

18–20 Jael greeted Sisera as “lord” (GK 123), in deference, he thought, to his lofty military title. Her offer of refuge was tempting, for who would search for him in a woman’s tent? Besides, the law of hospitality among nomads guaranteed the safety of one’s guests. Jael put a covering over the exhausted leader and gave him some milk (probably a kind of yogurt or curdled milk; 5:25). Though Jael’s kindness convinced Sisera of his safety, he took one more precaution by asking her to mislead any potential searching party.

21 When Sisera had fallen into a deep sleep, Jael picked up a wooden mallet and a tent peg and drove the peg into his temple, with enough force to hammer the tent peg into the ground. Women normally did the work of putting up and taking down the tents; so Jael knew how to handle her tools. Although Jael’s action was a startling violation of hospitality, Sisera was a man who had “cruelly oppressed the Israelites for twenty years” (4:3). Since he had had no mercy on God’s covenant people, Sisera probably lay under the sentence of “total destruction” placed on the Canaanites in general (Dt 7:2; Jos 6:17; see comment on Jos 2:10). Victory over the enemy was usually not considered complete until the leaders were eliminated, and in specific cases the Lord demanded that their lives be taken.

22 When Barak finally tracked Sisera down, Jael showed him the dead commander. Deborah’s prediction had come true; Barak lost the honor of vanquishing his chief rival. Sisera had died at the hands of a woman—in that culture a disgraceful death (cf. 9:54).

23–24 The rout of Sisera’s army broke the power of Jabin, king of Canaan. Without his commanding general, he succumbed to the Israelite forces. His eventual destruction doubtless includes the loss of his capital at Hazor.

2. The poetic version—the Song of Deborah (5:1–31)

The victory over the Canaanites was also commemorated in a poem of rare beauty. Called the “Song of Deborah,” this masterpiece expresses heartfelt praise to God for leading his people in triumph. It is a hymn of thanksgiving, a song of victory like Ex 15 or Ps 68. The poetry itself is magnificent, featuring many examples of climactic parallelism (vv.7, 19–20, 27) and onomatopoeia (v.22). Deborah is usually considered the author; the connection between prophetess and music is a natural one (cf. Ex 15:20–21).

a. Praise to God for his intervention (5:1–5)

1 A prose verse similar in form to Ex 15:1 introduces the song. Both songs commemorate the supernatural overthrow of horses and chariots.

2 The opening line can also be translated “When locks of hair grow long in Israel,” alluding to the practice of leaving hair uncut to fulfill a vow (Nu 6:5, 18). This then connotes dedication to the Lord in participating in a “holy war” (cf. Dt 32:42). The willingness of the people to fight for the Lord is emphasized in the second line. “Praise” (GK 1385) is literally from the verb “to bless.”

3 Out of deep gratitude for God’s motivating work among the people, Deborah lifted her heart to the One worthy of praise. She wanted “kings” and “rulers” (GK 8142) to hear about the God of Israel and his magnificent victory. The song is directed to “the LORD” (GK 3378), the name of God that expresses his covenant relationship with Israel.

4–5 These two verses describe a theophany (a visible, temporal manifestation of God), a characteristic of songs of victory (Ps 68:7–8). God’s intervention is compared with his awesome appearance at Sinai, where the covenant with Israel was established to the accompaniment of thunderstorm and earthquake (Ex 19:16–18). This is an apt reference, for the rains had been Sisera’s undoing and again revealed God’s transcendent power.

b. Conditions during the oppression (5:6–8)

6 Conditions were deplorable as Canaanite robbers roamed the highways, making travel dangerous. Commercial trading was likewise stopped, and the economy was being adversely affected.

7–8 Agriculture also was disrupted by the marauders. Life in unwalled villages was unsafe, and crops had to be abandoned. God had sent war and oppression because of their sin; now they were being effectively disarmed as well (or perhaps the large army did not dare to use their weapons against Sisera and his chariots). This lamentable situation continued until Deborah came on the scene. Her deep concern for the nation and her abilities as prophetess and judge inspired the people to take action. But first they had to give up the “new gods” they had chosen.

c. Challenge to recount the Lord’s victory (5:9–11)

9 Oppression and defeat have given way to triumph, as travelers can once more move about freely, and normal activities are resumed. The author’s heart goes out to the volunteers and leaders whose courage made this possible.

10–11 All classes of travelers are told to listen as the singers recount God’s great acts. Whether rich or poor, all would stop at the wells and have an opportunity to hear about the Lord’s “righteous acts.” The final two lines present the reverse of v.8: instead of war coming to the gates, people could now congregate there for normal judicial and business activities.

d. The roles of the individual tribes (5:12–18)

To throw off the Canaanite yoke, it was important for the tribes to cooperate in battle. Those who participated are commended, while the tribes who shirked their responsibility are condemned.

12 The section begins with a call to Deborah herself to awake. Normally “wake up” (GK 6424) is a plea to take action (Ps 44:23; Isa 51:9), and apparently Deborah had to be roused from her complacency as a judge (4:5). The song she is asked to “break out in” may have been a war song (cf. 2Sa 1:18). Barak (son of Abinoam; 4:6) too is called on to take captives, implying a convincing victory (cf. Ps 68:18; Eph 4:8).

13 The years of oppression had taken a heavy toll in lives. The verse may reflect a two-stage gathering of troops. First, volunteers may have joined their tribal leaders, before journeying together to the rallying point at Mount Tabor. The last phrase could be translated “against the mighty,” meaning the enemy.

14–15a Ephraim and Benjamin, two southern tribes, are mentioned first, perhaps because of their association with Deborah. The reference to Amalek is probably a geographical one (cf. 12:15). Makir usually refers to the half-tribe of Manasseh east of the Jordan, but here the western half is clearly intended (Jos 13:30–31) since the battle occurred within its borders. Zebulun is highly praised for its bravery. Along with Naphtali, they had responded to Barak’s initial summons (4:10). Issachar, located at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, also participated enthusiastically.

15b–16 Several tribes somewhat distant earned the author’s wrath for their inactivity. Apparently Reuben at least seriously considered sending some men, for their “searching of heart” is mentioned twice. The tribes from Transjordan had made an important contribution to the conquest under Joshua (cf. comment on Jos 1:12), but pressure from the Moabites may have influenced Reuben’s decision. The mention of campfires and flocks presents a tranquil picture in contrast with war cries and clashing armies.

17 Gilead was a common designation for much of Transjordan. The tribe of Gad possessed most of Gilead (Jos 13:24–25), though the half-tribe of Manasseh also lived there (Jos 13:31). “Reuben” and “Gilead” would thus include all three of the tribes across the Jordan.

The tribe of Dan had encountered difficulty in taking possession of their inheritance ever since the time of Joshua (cf. 1:34). It is not surprising, then, that they did not help solve this largely northern problem. The reference to “ships” implies that Dan had not yet migrated to the north. Asher, situated along the coast north of Carmel, had also failed to dislodge the Canaanites. Yet Asher was close enough to the oppressed area to have offered some assistance.

18 The aloofness of these tribes is sharply contrasted with the wholehearted efforts of Zebulun and Naphtali. Judah and Simeon are not mentioned, presumably because of their location far to the south.

e. The battle described (5:19–23)

The vividness of the poetry increases as the author uses repetition, satire, and concrete imagery to paint a lively picture. This poetic account should be closely compared with the description of the battle in 4:12–16.

19 The armies clashed at Taanach, near Megiddo, and the kings of Canaan were supremely confident of victory. With a touch of sarcasm, the author says that this time there was no plunder. They had robbed and oppressed the Israelites for the last time.

20–22 The Canaanites’ downfall came as God intervened. The reference to the participation of the stars may be a slap at astrological readings used by the Canaanites. As the rains fell, the river Kishon overflowed its banks; and chariots and riders were swept away. The surging river encouraged the Israelites to “march on” in pursuit of the enemy. The mighty horses of the foe were no match for the people of the God of Israel. In the context “thundering hoofs” seems to relate to a frantic retreat. The repetition of “galloping” (GK 1852) is a striking example of onomatopoeia in Hebrew.

23 The city of Meroz came under God’s curse, pronounced by the angel of the Lord, for failing to fight. Meroz was undoubtedly located in the heart of the oppressed area; so the condemnation of that community was more severe than that of the distant tribes. Since elsewhere in Judges cities refusing to participate in urgent battles were destroyed (8:15–17; 21:8–10), Meroz may have shared the same fate.

f. Jael praised for her deed (5:24–27)

24–27 In sharp contrast to the curse against Meroz is the blessing reserved for Jael, a woman who refused to remain neutral (see comments on 4:19–21). She initially treated Sisera in accord with his noble standing. But this once magnificent leader was quickly struck down. This heroine is compared to an expert archer, for the verbs “shattered” and “pierced” are used of arrows in Nu 24:8 and Job 20:24.

In v.27, the words “sank” and “fell” occur three times each, and “feet” occurs twice. This repetition builds up to the final and climactic word of the verse: “dead” (lit., “destroyed”). Sisera had been a mighty and devastating force against Israel, but now the destroyer was himself destroyed (cf. Isa 33:1).

g. Sisera’s mother’s futile wait (5:28–30)

28–30 The scene shifts from Jael’s tent to the luxurious home of Sisera. With a skillful, dramatic touch, the author reflects on the agonized waiting of Sisera’s mother for the return of her son. The long delay could mean that the illustrious warrior had tasted defeat, but his mother and her ladies-in-waiting console themselves with visions of plunder. It was common for soldiers to carry off beautiful maidens as trophies of victory (cf. 21:12). “Garments” were a special prize of war (cf. Jos 7:21; Zec 14:14), and Sisera as commander was sure to secure the most beautiful for his family.

h. Conclusion (5:31)

31 As in another song of victory (Ps 68:1–2), there is rejoicing over the fall of the wicked (cf. Nu 10:35). Reference to the sun and its strength closely parallels Ps 19:4b–6; Mal 4:2. The stunning defeat of Sisera resulted in forty years of peace for Israel.

F. The Victory of Gideon Over the Midianites (6:1–8:32)

The Gideon cycle is the longest segment of the book. Chapter 9 might also be counted as part of the Gideon story, since it describes the rule of his son. Under the inspiring leadership of this judge, the Israelites won a victory even more astonishing than that of Deborah and Barak.

l. Israel’s land devastated by the Midianites (6:1–6)

1–4 For the fourth time in Judges, the Israelites fell into sin. This time they found themselves at the mercy of invading Midianites. These desert dwellers, descended from Abraham and Keturah (Ge 25:2), lived generally to the south of Palestine. For seven years the camel-riding Midianites swept across the Jordan into the Valley of Jezreel at harvest time. With their speedy, wide-ranging mounts, they roamed all the way to Gaza, helping themselves to crops and animals. The Midianites were joined by the Amalekites—who had earlier assisted King Eglon of Moab (3:12–13)—and by other eastern peoples. Israel was helpless to resist the invaders and literally took to the hills to save their lives. It was a time of judgment comparable to the Day of the Lord (Isa 2:12, 19; 9:4).

5–6 The destruction was so great that it could be described in terms of a plague of locusts. Both in numbers and in effect, the invasion of the nomads matched the work of those devastating insects earlier mentioned as the inevitable outcome of disobedience (Dt 28:38; cf. Joel 1:4). The staple products of the land were no doubt hard hit by this yearly destruction (cf. Joel 1:11), including sheep, cattle, and donkeys (cf. Dt 28:31). The main areas affected had borne the brunt of the preceding Canaanite oppression. Manasseh suffered most, along with other tribes adjacent to the Jezreel Valley: Asher, Zebulun, and Naphtali (v.35).

2. Israel’s disobedience condemned by a prophet (6:7–10)

7–10 In their distress the Israelites once more cried out to the Lord. The last time this happened, God used the prophetess Deborah to bring deliverance (4:3–4). On this occasion the Lord sent a “prophet” (GK 5566) to pinpoint the cause of the oppression in words similar to those of the angel of the Lord in 2:1–4. Once again God reminded the people of their release from Egypt’s slavery, which should have resulted in perpetual devotion to the Lord. Instead, the Israelites had been worshiping the gods of the Amorites. Here “Amorites” is used generally of all the inhabitants of Palestine (cf. Ge 15:16). Israel refused “to listen to” (GK 9048) the Lord, a Hebrew idiom for disobedience (cf. 2:2).

3. Gideon challenged by the angel of the Lord (6:11–24)

11 The Lord’s instrument of deliverance was a young man from the tribe of Manasseh named Gideon. While he was threshing wheat in Ophrah, the angel of the Lord appeared to him there and sat under the oak tree (cf. 4:5). To hide the wheat and himself from the Midianites, Gideon was threshing in a winepress, a pit carved out of rocky ground. Normally threshing floors were located in exposed areas so that the wind could easily blow away the chaff.

12 The angel’s words seemed out of line with the timid actions of Gideon, and Gideon himself challenged their validity. Actually, the promise of the Lord’s presence was intended to encourage Gideon, just as the same assurance led Moses to take the Israelites out of Egypt. “The Lord is with you” is in fact the basic meaning of the name Yahweh (see comment on Ex 3:12–14). Gideon was called a “mighty warrior,” perhaps in anticipation of his remarkable bravery, or else a term that means he was of the upper class, the warriors who became the landed aristocracy.

13 Gideon did not recognize the visitor and complained that the oppression proved that the Lord was not with Israel. Like the psalmist (Ps 44.1–3, 9–16), Gideon contrasted the miracles everyone had heard about with the current inactivity of the Lord. Apparently Gideon was unaware of the prophet’s explanation in vv.8–10.

14 The heavenly guest is identified as the Lord himself, who was sending Gideon as Israel’s deliverer (cf. Ex 3:12; Isa 6:8–9). The strength Gideon possessed was the promise of the Lord’s presence with him.

15–16 It is difficult to know whether “Lord” (GK 151) means “sir” or “Lord,” for either is possible; in any case, Gideon came to recognize the supernatural character of the visitor only gradually. Gideon belonged to the weak clan of Abiezer, and his own position in his family division was not a prominent one. Yet God delights to use those who are young or humble and bring them to prominence (see 1Co 1:26–27). Gideon’s fears were somewhat relieved by the reassurance that with the Lord’s help he would be able to defeat the Midianites.

17–21 To obtain proof that God or his messenger was really talking to him, Gideon requested that his guest perform a miraculous sign, the first of three signs that Gideon was to see. First, however, Gideon received permission to bring his guest an offering. Since “offering” can mean “gift,” the food prepared by Gideon was partially an expression of hospitality. Unleavened bread is, of course, involved in many offerings; but it is sometimes served in quickly prepared meals (Ge 19:3). This was a substantial meal for such a time of scarcity, since the “ephah” of flour was about half a bushel. The angel instructed Gideon to use the rock—perhaps part of the winepress—as an altar. The fiery consumption of the meat and bread indicated the acceptance of Gideon’s offering and, together with the disappearance of the angel, provided the sign Gideon was seeking.

22–24 Gideon’s response was one of fright, for he knew that no one could see God face to face and live (Ex 33:20; cf. Jdg 13:22). Gideon was quickly assured that he would live, since the Lord promised him “peace” (GK 8934) and well-being. This peace included not only his personal welfare but also the restoration of Israel’s freedom and prosperity. Gratefully, Gideon built an altar to commemorate the Lord’s promise.

4. The altar of Baal destroyed and Gideon’s life imperiled (6:25–32)

25–26 Almost immediately the Lord asked Gideon to respond to his call to deliver Israel from Midian by taking decisive action in his own family. Even his father had espoused the Baal cult, leading the community in the worship of this pagan deity. Through Moses, God had said that altars to Baal and their accompanying Asherahs must be torn down (Ex 34:12–13; Dt 7:5; cf. Jdg 2:2). Baal worship was popular, however, and Gideon knew he was risking his life by obeying the Lord.

Part of Gideon’s task was to sacrifice a bull on a new altar dedicated to the Lord. Bull worship was closely associated with Baal and his father, El, and this particular bull was doubtless reserved for the Baal cult. If two bulls were intended, one might have been used to break down the pagan altar. The altar of the Lord was to be set up on top of a “height” (i.e., a “bluff” or “stronghold”), a prominent place where the city residents may have found refuge from the Midianites. Pieces of wood from the sacred pole would supply fuel for the burnt offering.

27–30 Gideon followed the Lord’s orders at night, correctly anticipating that his deeds would arouse the anger of the populace and his own relatives. Apparently one of Gideon’s ten servants revealed the identity of Baal’s enemy to the townspeople, and they demanded Gideon’s death. How different from Dt 13:6–10, where Moses commanded that even close relatives must be stoned for idolatry! The heresy had become the main religion.

31 Joash refused to put his son to death, arguing that a deity like Baal could defend himself. To interfere was an insult to Baal punishable by death. Joash’s seemingly honest appeal to Baal may reflect his own doubt in the power of a deity who could not deliver them from the Midianites.

32 Gideon was probably called Jerub-Baal (“Let Baal contend [with him]”) as a derogatory name, indicating the certain judgment the people expected him to face. When no harm came to him, the name became a reminder of Gideon’s great victory over Baal.

5. Gideon’s army (6:33–35)

33 The crisis in Ophrah was soon eclipsed by the annual invasion of the Midianite coalition. This was their eighth incursion into the fertile Valley of Jezreel, and it came during the wheat harvest in May or June (v.11).

34–35 This time, however, the enemy was not to feast without a fight. The Spirit of the Lord “came upon” (lit., “clothed”; GK 4252) Gideon (cf. 2Ch 24:20–21; Isa 51:9; Lk 24:49), already encouraged by his initial obedience. Like Ehud (3:27), Gideon sounded the trumpet of alarm to gather the troops. The men of his own clan of Abiezer were the first to follow him—an indication that they now shared Gideon’s attitude toward Baalism. Then the rest of Manasseh and the other northern tribes came to oppose the Midianites. Ephraim was not invited, perhaps because Gideon feared that this powerful “brother” tribe would not accept his leadership (cf. 1:22; 8:1–3).

6. The fleece (6:36–40)

36–38 Gideon’s confidence in God’s promises was far from complete and needed to be bolstered frequently. As in the previous instance (v.17), Gideon again asked for a sign to confirm God’s favor and word (cf. Ge 24:12–14). Gideon felt that if the fleece only was wet with dew and not the surrounding ground, that meant the Lord was with him. As Gideon requested, so it was: the fleece was saturated with dew, but the ground was dry.

39–40 The wool fleece would absorb the dew more readily than the hard ground of the threshing floor; so the second test required an even greater miracle. When Gideon made the second request, he knew the Lord would be unhappy with his weak faith. The wording of v.39 is remarkably close to Abraham’s final plea on behalf of Sodom (Ge 18:32).

Like Gideon, many a believer whose faith needed bolstering has “put out the fleece” to help him find the Lord’s will. If this “fleece” consists of a careful observation and interpretation of God’s leading through circumstances, the procedure can be a healthy one. But Gideon’s method was to make purely arbitrary demands of God and insist on immediate guidance. Despite Gideon’s lack of faith and insistence on a second sign, God in mercy not only chose to withhold punishment but condescended to answer him.

7. Gideon’s army reduced (7:1–8a)

1 With his hastily assembled army, Gideon set up camp at En-Harod, at the foot of Mount Gilboa. The Midianite hordes were located some four miles north of them in the Jezreel Valley, at a place about ten miles west of the Jordan. The invaders knew about this 32,000-man army and their leader (v.14), but apparently they did not view them as a serious threat.

2–3 The Lord’s instructions probably came as a surprise to Gideon, who was already outnumbered four to one. But the size of the army was not the crucial factor: God could give victory to a few men as easily as to a large army (cf. 1Sa 14:6). Lest Israel take credit for her achievements, the Lord began to remove all ground for boasting. The first stage in the troop reduction was to allow the cowardly to go back home. Their fear might prove contagious and ruin the campaign (cf. Dt 20:8). More than two-thirds of Gideon’s army left the scene.

4–6 The Lord, however, informed Gideon that the army had to be reduced even further. A special “screening” was setup based on the way the 10,000 drank water. This strange procedure netted a total of 300 men who apparently crouched down to scoop up water by using their hands as a dog uses its tongue. All the others dropped to their knees before drinking.

7–8a Possibly the 300 displayed a greater alertness in staying on their feet, but in actuality they may have been no more courageous than the 9,700 others. When v.8a says that Gideon “kept” (GK 2616) the 300, it implies that they too had a strong urge to vanish with their colleagues (this expression is used in 19:4 for a person detained against his will). If these 300 men were beginning to tremble, the need for God’s intervention became even greater. Before departing the 9,700 gave the remaining soldiers their provisions and their trumpets. The large number of trumpets that Gideon acquired (cf. v.18) implies that a surprise attack was in the planning.

The story of Gideon begins with a graphic portrayal of one of the most striking facts of life in the Fertile Crescent: the periodic migration of nomadic people from the Aramean desert into the settled areas of Palestine. Each spring the tents of the bedouin herdsmen appear overnight almost as if by magic, scattered on the hills and fields of the farming districts. Conflict between these two ways of life (herdsmen and farmers) was inevitable.

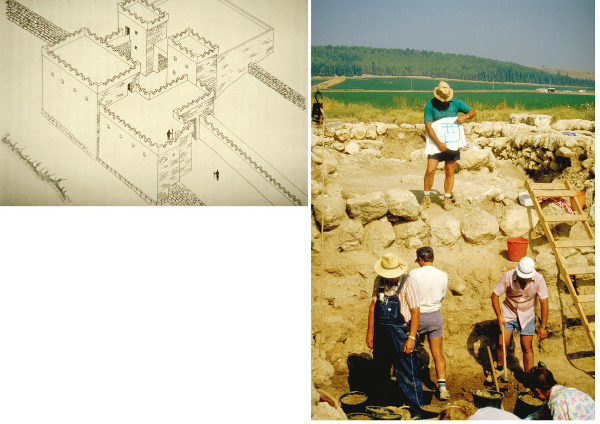

In the Biblical period, the vast numbers and warlike practice of the herdsmen reduced the village people to near vassalage. Gideon’s answer was twofold: (1) religious reform, starting with his own family; and (2) military action, based on a coalition of northern Israelite tribes. The location of Gideon’s hometown, “Ophrah of the Abiezrites,” is not known with certainty, but probably was ancient Aper (modern Afula) in the Valley of Jezreel.

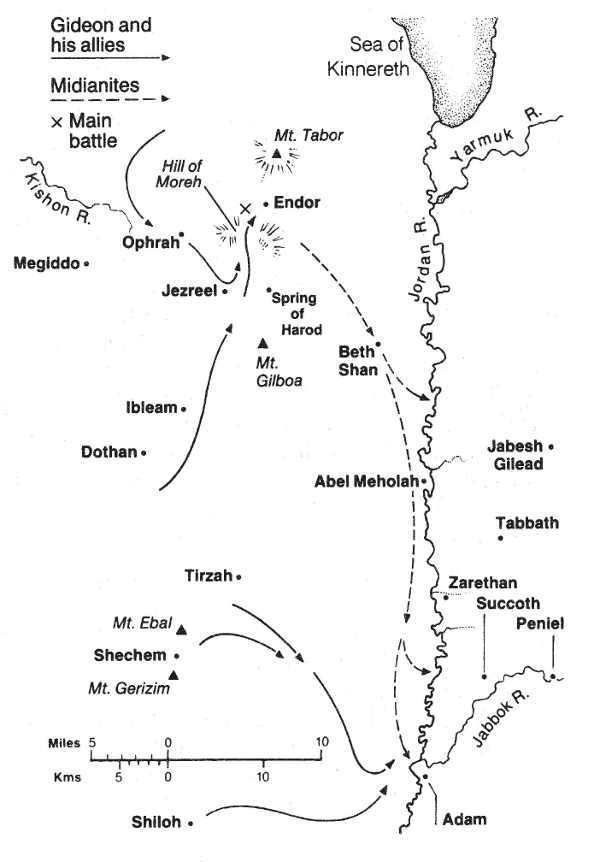

The battle at the spring of Harod is justly celebrated for its strategic brilliance. Denied the use of the only local water source, the Midianites camped in the valley and fell victim to the small band of Israelites, who attacked them from the heights of the hill of Moreh.

The main battle took place north of the hill near the village of Endor at the foot of Mount Tabor. Fleeing by way of the Jordan Valley, the Midianites were trapped when the Ephraimites seized the fords of the Jordan from below Beth Shan to Beth Barah near Adam.

8. Gideon’s victory confirmed by a dream (7:8b–14)

8b–12 With less than one percent of his original army, Gideon’s faith again began to waver. For the third time God gave him a sign, and at last Gideon was thoroughly convinced. Any promise or action repeated three times was regarded as the surest confirmation (16:15; Nu 24:10). Before he attacked, Gideon and his aide Purah, who was probably his armor-bearer (9:54), paid a visit to the Midianite camp. What he was to hear would encourage him tremendously.

The foe spread out before them seemed innumerable (cf. Jos 11:4; 1Sa 13:5), while Gideon could count the available Israelites all too easily.

13–14 Gideon and his servant overheard two of the enemy soldiers discussing a dream. In the ancient world dreams were considered an important means of divine communication (1Sa 28:6; cf. Ge 20:3–6; 37:6–; et al.). The enemy soldier was able to interpret the dream and predict Gideon’s victory. Barley bread could represent Israel as a cultivator of the soil. The key to the interpretation of the dream is that the word translated “came tumbling” (lit., “overturning”; GK 2200) can be applied also to swords (cf. its use in Ge 3:24). The “overturning” or “overthrow” of the tent represented the collapse of the nomadic forces.

9. Preparation for the battle (7:15–18)

15 Gideon realized that what he had heard was far more than a coincidence; so he immediately prostrated himself in grateful worship before the Lord. Now ready to fight, Gideon returned to prepare his men for the historic battle.

16–18 The only orthodox part of Gideon’s instructions was to divide the men into three groups (cf. 1Sa 11:11; 2Sa 18:2). By spreading out around the Midianites, Gideon’s troops would create the impression of being a much larger army. The “trumpets” (GK 8795) were the same ram’s horn type used by Ehud and Gideon (3:27; 6:34) to summon the troops. Only the leaders would give signals on the trumpets, so three hundred trumpets normally represented a sizable army. When Joshua captured Jericho, only seven priests had trumpets (Jos 6:6).

The empty jars were used to hide the light of the torches until the proper moment arrived. The soldiers may have been mystified as to the actual purpose of such unusual weapons, but their orders were to follow Gideon’s example carefully. After blowing the trumpets, they were to shout the war cry (v.20).

10. The Midianites routed (7:19–25)

19–20 Gideon and his men disrupted the Midianite camp sometime between ten o’clock and midnight, striking just after new guards had been posted. The Israelites’ main weapon was noise; and between the trumpet blasts and the smashing of jars, they achieved the intended effect of demoralizing the Midianites. Once the jars were broken, three hundred torches lit up the night, apparently at the head of vast columns of troops. To add to the nightmare, a ringing battle cry pierced the night air.

21–22 These startling developments quickly produced panic, a normal occurrence when God led his people into battle. The Midianites were convinced that a powerful army was about to massacre them. The people ran about, shouting and trying to escape as fast as possible. In all the confusion they began fighting among themselves, thinking that enemy forces were already in their camp. Finally, to avoid the slaughter, the Midianite hordes fled toward the Jordan and the safety of the desert beyond.

23–25 To help in the pursuit, Gideon summoned reinforcements, perhaps including many of his original 32,000. Their courage restored, they gladly rushed after the foe. Gideon also called on the powerful tribe of Ephraim to cut off the Midianites at the fords of the Jordan (cf. 3:28). Many of the enemy forces had not yet crossed when the men of Ephraim attacked them and captured Oreb and Zeeb, probably leading generals of the army. The two were promptly put to death at sites later named to commemorate the occasion (cf. Isa 10:26). When the Ephraimites met with Gideon in 8.1–3, they brought along the heads of these leaders.

11. The Ephraimites’ complaint (8:1–3)

1–3 The tribe of Ephraim had a proud heritage (see 1:22) and felt insulted by Gideon’s failure to call on them earlier. They had cooperated honorably with Ehud (3:26–29) and Barak (5:13–14a) and wondered why they were left out this time. Gideon decided to adopt a course of appeasement. He praised them for their great victory over Oreb and Zeeb, assuring them that in comparison his accomplishments were small. In a sense Ephraim received the “leftovers” (NIV, “gleanings”). These, however, were more substantial than the initial victory (“harvest”) won by his little Abiezrite clan. Gideon’s flattery calmed their anger and avoided the civil war that later flared up between Ephraim and Manasseh (12:4–6). “A gentle answer turns away wrath” (Pr 15:1).

12. Lack of cooperation from Succoth and Peniel (8:4–9)

4–6 The narrative now shifts back to the exploits of the “three hundred.” Gideon was faced with an attitude exactly the opposite of Ephraim’s as two cities completely rejected his request for help. The tiny army was now some forty miles from the hill of Moreh when they came to Succoth, just north of the Jabbok River. Worn out from the long chase, Gideon asked these residents of Gad for some provisions. The men of Succoth reasoned that the fleeing Midianites would soon regroup and easily defeat the makeshift army thrown together by Gideon. Any assistance given to Gideon would implicate Succoth and bring certain retaliation from the feared nomads. The question in v.6 apparently refers to the custom of cutting off the hands of dead victims as a convenient body count (1Sa 18:25; cf. Jdg 1:6).

7 The sarcastic, unpatriotic response of the leaders of Succoth brought a sharp retort from Gideon. Perhaps the tribes of Transjordan could be excused for failing to aid Deborah and Barak (5:17), but neutrality was impossible when the conflict was on their soil (cf. 5:23). Gideon promised that when he returned in victory, he would severely punish the city.

8–9 Moving six miles east, Gideon received the same response from the people of Peniel. In the very place where Jacob had met with God and had his name changed to Israel (Ge 32:28–30), these descendants of his refused to believe that God could give victory over the Midianites. Gideon vowed that he would soon demolish the fortified tower that had made Peniel an important city.

13. The capture of the kings of Midian (8:10–12)

10–12 True to his word, Gideon pressed farther into Transjordan, following the caravan trail taken by the Midianites. By this time the remnants of the Midianite army were in Karkor, east of the Dead Sea. No doubt the Midianites believed they were safely out of range of the pursuing armies, but again Gideon surprised them and routed them.

Gideon’s main goal was the capture of Zeba and Zalmunna, Midian’s two kings, for without leadership the eastern hordes were not likely to resume their raids. The two kings probably belonged to different tribal groups.

14. Retaliation against Succoth and Peniel (8:13–17)

13–17 The resounding victory over Midian did not deter Gideon from severely disciplining these two delinquent cities. A young man from Succoth was compelled to write down the names of the “princes” or “elders.” The seventy-seven men who were registered on this death list heard Gideon repeat their earlier taunt before carrying out the punishment. Like their neighbors in Peniel, the men of Succoth doubtless died for their guilt.

15. The Midianite kings slain (8:18–21)

18 The scene probably shifts across the Jordan, so that Gideon could display his captives to the main body of Israelites. The presence of his young son, Jether, also points to a location nearer home. After viewing the vengeance taken by Gideon on fellow Israelites, the Midianite kings did not hold out much hope for their own survival. In fact, they seemed to prefer death by admitting they had killed Gideon’s full brothers—a slaughter that may have occurred during one of their earlier campaigns, when opportunity for revenge seemed remote.

19 Gideon had considered sparing the kings’ lives, but the additional element of personal revenge made their death certain. Moreover, the death of enemy leaders almost always accompanied total military victory (3:21–25; 4:21–22; 9:55; Jos 10:26).

20–21 Gideon gave the honor of executing the kings to his firstborn son, Jether. The lad shunned this gruesome task, and the kings quickly pointed out that this was a man’s job. For them it would be more honorable and less painful to be killed by a renowned warrior like Gideon. Death at the hands of a boy or a woman was considered a disgrace (5:24–27; 9:54). Gideon complied with their final request.

16. Gideon’s ephod (8:22–27)

22–23 Gideon’s celebrated victory brought him an invitation to become king over Israel and establish a ruling dynasty. Under unified rule, the Israelites felt they could better prevent any future oppression. Gideon rejected the offer, for God was their king, and the people needed to renew their allegiance to him.

24–26 While refusing the throne, Gideon did in fact assume many of the prerogatives of a king; he established a large harem (v.30), amassed a fortune (v.26), acquired royal robes, and made an ephod to consult God (v.27). He also accepted gifts from his grateful soldiers. Most of the items given to Gideon were those usually worn by women in Israel: “earrings” (perhaps “noserings”; cf. Ge 24:47; Eze 16:12), “pendants,” and “chains” or “necklaces” (cf. SS 4:9). This vast repertoire of jewelry may have been a factor in Gideon’s accumulation of wives.

Verse 24 contains the only reference in Judges to the Ishmaelites. Apparently this was an inclusive term for Israel’s nomadic relatives and alternated freely with “Midianites” (cf. Ge 37:25–28; 39:1).

27 With the gold Gideon surprisingly made an ephod that was to lead Israel into idolatry. The high priest wore an ephod, an apronlike garment made of linen, various colors of yarn, and gold thread (Ex 39:2–5). The breastpiece attached to it contained the mysterious Urim and Thummim (Ex 28:28–30), used to consult God (1Sa 23:9–10); this may have been Gideon’s purpose in making a golden replica. Gideon seems to have wrongly assumed priestly functions. The ephod eventually served an idolatrous purpose and is described in the same terms as the gods of Canaan (2:2, 17). Gideon, who had boldly broken up his father’s altar to Baal, was now setting a trap for his own family.

17. Gideon’s accomplishments and death (8:28–32)

28–31 Midian had been thoroughly disgraced and caused no further trouble. Gideon himself spent the remainder of his life in Ophrah. His many wives and sons reflected his prosperity (cf. 2Ki 10:1, 4; 12:9, 14). The hatred and murder that plagued Gideon’s family after his death (cf. ch. 9) are characteristic of OT polygamous situations. Among Gideon’s wives was a concubine from Shechem. Apparently she continued to live in her hometown and remained under the authority of her father. In such marriage relationships the husband was expected to visit from time to time (cf. 15:1). It is the son of this low-ranking wife who rises to prominence in the next chapter.

32 Gideon’s death notice further attests his importance; only he and Samson were buried in the tomb of their fathers. To die “at a good old age” implies a long and full life (Ge 15:15; 25:8; 1Ch 29:28).

G. The Brief Reign of Abimelech (8:33–9:57)

1. Apostasy after Gideon’s death (8:33–35)

33 Abimelech is not called a judge, nor was he raised up by God to rescue Israel. Since he was the son of Gideon, this period stands in a unique relationship with the preceding one. Again the Israelites became enamored with Baal worship, and particularly Baal-Berith (cf. 2:11), whose worship was centered at Shechem. Baal-Berith means “Baal of the covenant” and may indicate that they had made a covenant with Baal.

34–35 By worshiping Baal-Berith, Israel deserted the God who had made a covenant with them at Sinai and who had repeatedly been their Savior. They also quickly forgot the benefits won for the nation by Gideon. Calling Gideon Jerub-Baal here recalls Baal’s inability to “defend himself” against Gideon (see 6:27–32).

2. Abimelech’s rise to power (9:1–6)

1 In a polygamous society the relatives of one’s mother can provide refuge and support for an ambitious prince. Abimelech was probably spurned by his half-brothers because of his mother’s lowly status (cf. 11:1–2); so he appealed to his mother’s brothers for help.

Shechem (between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim) lay on important caravan routes. Since no mention is made of the capture of Shechem during Joshua’s conquest of Canaan, possibly a treaty was made with that city soon after the invasion (see Jos 8:30–35; 24:1–27—two covenant renewal ceremonies that took place at Shechem). The people of Shechem maintained a link with the Canaanite founders of the city, and perhaps Abimelech’s mother herself was a Canaanite.

2–4 Abimelech’s appeal was based on the tenuous claim that his step-brothers’ rule would not have Shechem’s best interests at heart. In fact, it is unlikely that Gideon’s sons intended to dominate an area thirty miles south of Ophrah. The residents of Shechem, however, agreed to his plan and provided a substantial sum to carry it out. Temple treasures were often used for military and political ends (cf. 1Ki 15:18). The individuals hired were a worthless band (cf. 11:3; 2Ch 13:7).

5–6 Treacherous and unstable, these mercenaries helped Abimelech commit wholesale fratricide. But mass murders are rarely a total success, and Jotham managed a narrow escape (cf. 2Ch 22:10–12). Nevertheless, Abimelech became the first person ever to be crowned as king in Israel. His abortive rule ran roughshod over the divine requirements for that office (cf. Dt 17:14–20). His coronation ironically took place near the tree in Shechem where Joshua had solemnly placed the “Book of the Law” (Jos 24:26). Beth Millo (lit., “house of the fill”) is likely the same as the “tower of Shechem” of v.46. The word “fill” comes from the huge earthen platform on which these structures were built.

3. Jotham’s fable (9:7–21)

The sole survivor of Abimelech’s purge delivered an incisive evaluation of his half-brother’s rule. Presented in allegorical form, this story of the trees effectively lays bare Abimelech’s true character and the utter disregard of the people of Shechem for Gideon’s memory.

7–9 Jotham traveled to Shechem and climbed Mount Gerizim’s eight-hundred-foot slope south of the city. There, at a safe distance from his audience, he pronounced a powerful curse (cf. v.57).

The introduction to the fable contains an unusual reference to God as the One who listened to them. By this statement Jotham may be asking the hearers to present to God a response to his arguments. For the comparison of kings to trees, see also Isa 10:33–34. In recognition of Israel’s lowly status, Jotham began, not with a cedar, but with an olive tree. Olives were used for food, ointment, and medicine; they were one of Israel’s most valued crops (Dt 11:14). Olive oil kept the lamps in the Holy Place burning constantly, thus “honoring” the Lord. In view of its important functions, the olive tree declined the offer to become king.

10–11 The fig tree likewise passed up the opportunity to rule. Like olives, figs were a key agricultural product. Israel’s picture of the ideal age was for every man to sit under his vine and under his fig tree (Mic 4:4; cf. 2Ki 18:31).

12–13 Predictably, the vine also refused. Its fruit was the main beverage of the land, and libations of wine accompanied many sacrifices at the sanctuary (Nu 15:10).

14–15 At last “the thornbush” was called on; and, having nothing better to do, the surprised shrub gladly agreed to reign. This plant was a menace to agriculture and had the quality of burning quickly (Ps 58:9). Since it provided little if any shade, its “refuge” is spoken of sarcastically. It could only threaten to destroy, if its rule were not accepted.

16–20 By this time Jotham’s main point was clear, but he gave a detailed interpretation. Gideon probably represented one of the good trees invited to become king (8:22), though exact identifications are not needed. Noble, capable leaders like Gideon believed that the theocracy, not a monarchy, was the best form of government. Abimelech was the thornbush king. Along with the Shechemites, he was guilty of a terrible crime against Gideon, who had saved them at the risk of his own life. He really had nothing to offer the people. Abimelech’s mother is called a “slave girl,” a term usually referring to a wife’s servant who is also a concubine (Ge 21:12; 30:3).