INTRODUCTION

1. Title

In the Jewish canon the two books of Samuel were originally one. Like Kings and Chronicles, each of which is slightly longer than Samuel, the scroll of Samuel was too unwieldy to be handled with ease and so was divided into two parts in early MSS of the LXX. Not until the fifteenth century A.D. was the Hebrew text of Samuel separated into two books. It is understandable that the ancient Hebrew title of the book was “Samuel,” since the prophet Samuel is the dominant figure in the early chapters.

2. Authorship and Date

According to the Babylonian Talmud, the judge and prophet Samuel wrote the first twenty-four chapters of 1 Samuel (1Sa 25:1 reports his death), and the rest of the Samuel corpus was the work of Nathan and Gad (the latter theory is based on 1Ch 29:29). But we cannot say for certain that this is the case. The priests Ahimaaz (cf. 2Sa 15:27, 36; 17:17, 20; 18:19, 22–23, 27–29) and Zabud (cf. 1Ki 4:5), among others, have also been proposed as possible candidates. All arguments about authorship fail to convince. In sum, we must remain content to leave the authorship of Samuel in the realm of anonymity. Ultimately, of course, the Holy Spirit is the Author.

A statement in 1Sa 27:6 has often been referred to in discussions of authorship: “Ziklag . . . has belonged to the kings [pl.] of Judah ever since.” This verse suggests that Samuel was not written until after the division of the kingdom of Israel following the death of Solomon in 931 B.C. But we must reckon with the possibility of a modest number of later editorial updatings and/or modernizations of the original work. With respect to the date of the books of Samuel, all that can be said for certain is that since they report “the last words of David” (2Sa 23:1), the final chapters could not have been written earlier than the second quarter of the tenth century B.C. (David died c. 970).

3. Historical Context

After the conquest of Canaan by Joshua, the people of Israel experienced the normal range of problems that face colonizers of newly occupied territory. Exacerbating their situation, however, was not only the resilience of the conquered but also the failures—moral and spiritual as well as military—of the conquerors. Their rebellion against the covenant that God had established with them at Sinai brought divine retribution, and the restoration that resulted from their repentance lasted only until they rebelled again (cf. Jdg 2:10–19; Ne 9:24–29). By the end of Judges the situation in the land had become intolerable. Israel was in extremis, and anarchy reigned (Jdg 17:6; 21:25). More than three centuries of settlement (cf. Jdg 11:26) did not materially improve Israel’s position, and thoughtful people must have begun crying out for change.

If theocracy implemented through divine charisma was the hallmark of the period of the judges (cf. Jdg 8:28–29), theocracy mediated through divinely sanctioned monarchy would characterize the next phase in the history of the Israelites. In the days of the judges “Israel had no king” (Jdg 17:6; 18:1; 19:1; 21:25), and it was becoming increasingly apparent to many that she desperately needed one. Not until the accession of Saul did the people have a king in the truest sense of the word—and even then they expected him to “judge” them (cf. 1Sa 8:5–6, 20).

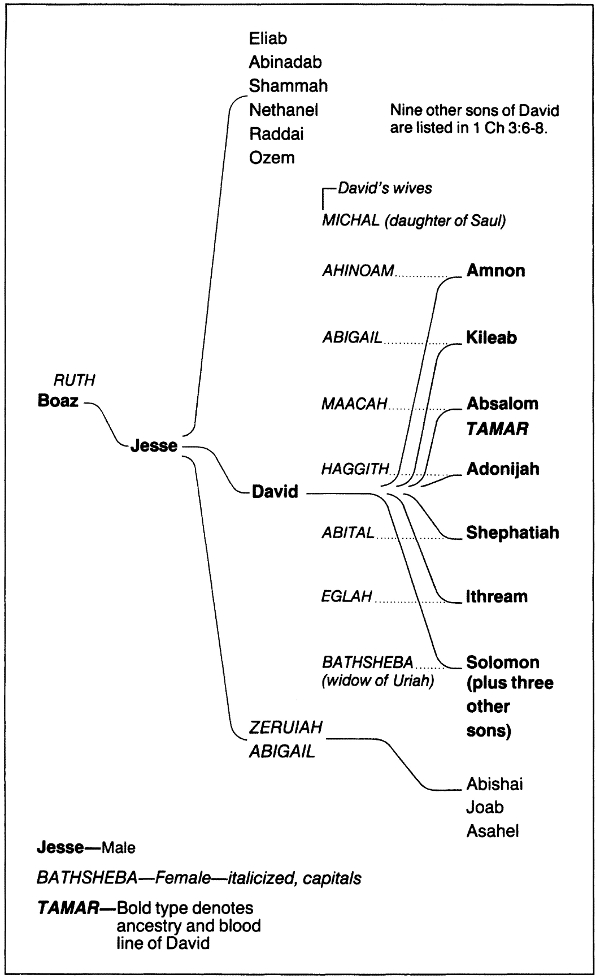

Historically, the division of the monarchy occurred in 931/30 B.C., following Solomon’s death. If we interpret the biblical figures literally, Solomon reigned from 970 to 931 (forty years, 1Ki 11:42), David from 1010 to 970 (forty years and six months, 2Sa 5:5), and Saul from 1052 to 1010 (forty-two years, 1Sa 13:1). Assuming that Samuel was about thirty years old when he anointed Saul as king of Israel, we arrive at the approximate dates of 1080 (the birth of Samuel) to 970 B.C. (the death of David) as the time span covered in the books of Samuel.

4. Purpose

In the books of Samuel, monarchy becomes a reality. Three figures dominate the book—Samuel the king-maker, Saul the abortive king, and David the ideal king. A major purpose of Samuel, then, is to define monarchy as a gracious gift of God to his chosen people. Their desire for a king (1Sa 8:5) was not in itself inappropriate, despite Samuel’s initial displeasure (v.6). Nor were they necessarily wrong in wanting a king like “all the other nations” had (vv.5, 20). Their sin was that they were asking for a king “to lead us and to go out before us and to fight our battles” (v.20). They were willing to exchange humble faith in the protection and power of “the LORD Almighty” (1Sa 1:3) for misguided reliance on the naked strength of “the fighting men of Israel” (2Sa 24:4).

5. Literary Form

Justifiable concern for the inspired truth and moral excellence of Scripture should not blind us to its consummate beauty. For the most part the books of Samuel are composed of prose narratives that serve well in presenting a continuous historical account of the advent, establishment, and consolidation of monarchy in Israel. It is possible to isolate various literary units within the larger whole—e.g., the Ark Narratives (1Sa 4:1b–7:17), the Rise of Saul (chs. 8–12), the Decline of Saul (chs. 13–15), the Rise of David (16:2–28:2), etc.—although debate is vigorous concerning their parameters.

In recent years various sections of the books of Samuel have been subjected to close reading in order to uncover aspects of Samuel’s exquisite literary structure. While manufacturing chiasms where there are none is a constant temptation that the exegete must avoid at all costs, the author of Samuel seems to have used the technique on numerous occasions. A clear example is the Epilogue, in which the Song of David (2Sa 22) and David’s Last Words (23:1–7) nestle between two warrior narratives (21:15–22; 23:8–39) that are framed in turn by reports of divine wrath against the people of God (21:1–14; 24).

Second Samuel 1–20 displays a four-part architectonic structure that is impressive indeed. David’s Accession to Kingship Over Judah (1:1–3:5) ends with a four-verse listing of the sons born to David in Hebron (3:2–5); David’s Accession to Kingship Over Israel (3:6–5:16) ends with a four-verse listing of the children born to him in Jerusalem (5:13–16); David’s Powerful Reign (5:17–8:18) and David’s Court History (chs. 9–20) each end with a four-verse roster of his officials (8:15–18; 20:23–26). A symmetrical literary edifice of such magnitude can hardly be accidental.

When poetry punctuates the corpus here and there, it does so in memorable and striking ways. For example, the Song of Hannah and the Song of David—the first near the beginning of the work (1Sa 2:1–11) and the second near its end (2Sa 22)—remind us that the two books were originally one by framing their main contents, by opening and closing in similar ways, and by highlighting the messianic horizons of the Davidic dynasty through initial promise (1Sa 2:10) and eternal fulfillment (2Sa 22:51).

6. Theological Values

In terms of the political scene, Israel at the beginning of 1 Samuel was a loosely organized federation of anemic tribal territories scarcely able to keep the Philistines and other enemies at bay. By the end of 2 Samuel, however, Israel under David had become the most powerful kingdom in the eastern Mediterranean region, strong at home and secure abroad. As far as the religious picture is concerned, the opening chapters of 1 Samuel find Israel worshiping at a nondescript shrine presided over by a corrupt priesthood. The last chapter of 2 Samuel, however, records David’s purchase of a site in Jerusalem on which the temple of Solomon would be built. Sweeping change, then, is a hallmark of the Samuel narratives—changes guided and energized by the Lord himself through humans like Samuel, Saul, and David.

Election is also important in the books of Samuel. The Lord’s elective purpose embraced Samuel (cf. 1Sa 1:19–20), Saul (cf. 10:20–24), and David (cf. 16:6–13). 2 Samuel 7 describes God’s choice of the dynasty of David as that through which future kings (including the Messiah) would come. In 2Sa7, kingship and covenant kiss each other.

Reversal of fortune as an index of divine sovereignty and grace is another significant theme. Hannah, a barren woman, becomes the mother of six children (cf. 1Sa 1–2). Men of privilege (such as Eli’s sons) die in shame (cf. 4:11). An unheralded donkey wrangler (cf. 9:2–3) and an obscure shepherd boy (cf. 16:11) are anointed as the first two rulers of Israel.

A key theme of the ark narratives is that God refuses to be manipulated. Carrying the ark into battle does not guarantee an Israelite victory (cf. 4:3–11), placing the ark in a Philistine temple does not ensure divine blessing (cf. 5:1–6:12), and looking into the ark brings death (cf. 6:19; 2Sa 6:6–7). The ark, with its tablets of the covenant, served as a continual reminder to the Israelites of God’s demands on their lives.

The Deuteronomic theme of blessing for obedience and curses for disobedience is furthered in the books of Samuel. To the extent that David understood that his role as human king was to implement the mandates of the Divine King (Israel’s true ruler), blessing would follow (cf. 2Sa 6:11–15, 17–19; 7:27–29). When he deliberately flouted God’s will, however, he could count equally on the fact that he would be under the curse (cf. 12:1–18). If the Davidic covenant was eternal in the sense that his line would continue forever (cf. 7:12–16, 25–29; Ps 89:27–29, 33–37), it was also conditional in that individual participants in it would be punished when they sinned (cf. 1Ki 2:4; 8:25; Pss 89:30–32; 132:12).

The offices of king and prophet arose simultaneously in Israel. Saul, the first king, was anointed by Samuel, who stands at the head of the prophetic line (cf. 1Sa 9:6–10, 19; Ac 3:24; 13:20) as promised to Moses (Dt 18:15–18). If the task of the king was to administer the covenant, that of the prophet was to interpret its demands. To the end of the monarchy, the prophets protected with holy zeal their divinely authorized claims over kingship.

EXPOSITION

I. Prelude to Monarchy in Israel (1:1–7:17)

First Samuel introduces us to Israel’s last two judges (Eli, a failure; Samuel, a success) and first two kings (Saul, a failure; David, a success). Appropriately the story of Israel’s monarchy begins with an account of the early life of Samuel: prophet, priest, judge, and, most significantly, king-maker. God chose Samuel to anoint Israel’s first two kings. Each was to be the “leader” over his people (10:1; 13:14; 16:13).

A. The Childhood of Samuel (1:1–4:1a)

1. The birth and dedication of Samuel (1:1–28)

1–2 “Ramathaim”—the town of Samuel’s birth, official residence, and burial—means “Two heights.” Elsewhere the town is called simply Ramah, “Height” (1:19; 2:11; 7:17; et al.).

Samuel’s father is called a “Zuphite” who lived in the area assigned to Ephraim. The Chronicles genealogies identify Samuel as a member of the Kohathite branch of the tribe of Levi and an ancestor of tabernacle and temple musicians (1Ch 6:16, 22, 31–33). Allotted no patrimony of their own, the Levites lived among the other tribes (see Jos 21:20–22). “Elkanah,” a popular name in ancient Israel, means “God has created [a son].” He is the only commoner in the books of Samuel and Kings specifically mentioned as having more than one wife. Although polygamy was not God’s intention (cf. Ge 2:24; Mal 2:15), having “two wives” accords with the polygamous culture of the ancient world.

Hannah (lit., “Grace”) initially has pride of place, probably because she was Elkanah’s favorite. Later, however, Peninnah (lit., “Ruby”) is mentioned first, no doubt because she was a prolific childbearer (cf. v.4). Barrenness was the ultimate tragedy for a married woman (cf. Ge 11:30; 15:2–4; 16:1–2; 25:5; et al.).

3–8 Three times a year all Israelite men were required to go to the central sanctuary to offer sacrifices at the main religious festivals (Ex 34:23; Dt 12:5–7; 16:16; cf. Lk 2:41). Shiloh (sixteen miles east of Ramah) had been the location of the tabernacle and the ark of the covenant (4:3–4; Jos 18:1; Jdg 18:31). Eli (“Exalted is [the Lord]”), the priest at Shiloh (v.9; 2:11) and a judge in Israel (4:18), was descended from Aaron’s son Ithamar (14:3; 22:20). Each of Eli’s two reprobate sons—unfortunately also priests—had an Egyptian name: Hophni (“Tadpole”) and Phinehas (“The Nubian”).

The festival in view here is probably the Feast of Tabernacles. Sacrifices were offered to the “the LORD Almighty” (or “the LORD of hosts”). Festival celebrations were times of rejoicing in God’s blessings, especially that of a bountiful harvest. Elkanah distributed portions of sacrificial meat (cf. Ex 29:26; Lev 7:33; 8:29) to Peninnah and her children, since family members shared in certain of the sacrificial offerings (cf. Dt 12:17–18; 16:13–14). Elkanah provided Hannah with a double portion because of his love for her. Hannah’s sterility likely prompted Elkanah to take Peninnah as his second wife, who thus became Hannah’s “rival.” She “kept provoking” Hannah to “grief” (v.16). The devout Hannah was content to allow the Lord to avenge the wrong committed against her (cf. 2Sa 3:39).

The “house of the LORD” refers to the tabernacle but apparently also includes more permanent auxiliary structures that had doors (3:15) and therefore doorposts (v.9). These sacred buildings are called “the LORD’s temple” (cf. 3:3).

Elkanah, mindful of Hannah’s grief, asked her (lit.), “Why is your heart bad?” To do something “with a bad [GK 8317] heart” means to do it resentfully (cf. Dt 15:10). Apparently he thought she was angry or spiteful because she did not have children. Thus Elkanah was asking Hannah, “Why are you resentful? Don’t I [your husband, who loves you very much] mean more to you than ten sons?”

9–11 Hannah’s misery peaked at Shiloh during an annual pilgrimage. Her sadness and “bitterness of soul” led her to pray and make a vow to the Lord for herself and a son. The Nazirite vow (supposed here) included (1) abstaining from the use of grapes in any form, (2) not shaving the hair on one’s head, and (3) avoiding dead bodies (Nu 6:3–7). The Nazirite vow was not usually taken by proxy and was rarely lifelong.

Hannah humbly calls herself “your servant” (GK 563), a word that indicates her submissive in the presence of a superior (cf. v.16; 3:9–10), and requests that God “look upon [her] misery” (cf. Ge 29:32; cf. 2Sa 16:12). God’s remembrance is not a matter of recalling to mind but of paying special attention to or lavishing special care on someone (cf. Ps 8:4). Hannah recognizes that children are always a gift of God. If he will “give” (GK 5989) her a son, in gratitude she will “give” him back to the Lord (but cf. Ex 22:29).

12–18 Hannah’s prayer reveals her intimate relationship with God. She prayed “to” the Lord; she prayed “in her heart”; and she prayed silently. Eli misunderstood Hannah’s actions. Prayer in the ancient world was almost always audible (cf. Pss 3:4; 4:1; 6:9; Da 6:10–11), and drunkenness was not uncommon at festal occasions. He can hardly be excused for his spiritual insensitivity and should have realized that Hannah’s moving lips signified earnest prayer rather than intoxicated mumbling. He therefore mistakenly rebukes her.

Hannah justly protests that she has been “pouring out [her] soul to the LORD,” a vivid idiom for praying earnestly (cf. Pss 42:4; 62:8; La 2:19). She declares herself to be “deeply troubled” and does not want Eli to mistake her for a “wicked woman.”

Satisfied with Hannah’s explanation, Eli tells her to “go in peace” (cf. 25:35). Eli’s hope that God would grant Hannah’s request is soon fulfilled in the birth of Samuel (v.27; cf. 2:20). Being assured by Eli’s response, she breaks her self-imposed fast, and her face is “no longer downcast.”

19–20 The next day Elkanah’s family worshiped the Lord, which had special meaning for Hannah this time. After their return from Shiloh to Ramah, Elkanah “lay with” (lit., “knew”; cf. Ge 4:1, 17, 25) Hannah. The Lord “remembered [GK 2349] her” by enabling her to bear a son. Hannah called him Samuel (lit., “Name of God”) and then punned on the name by saying that she had “asked” the Lord for him (the Hebrew for “asked” is found in the word “Samuel”).

21–23 After Samuel was born, Elkanah continued taking his family to Shiloh to sacrifice to the Lord (1:3; 2:19). On at least one occasion he had the additional purpose of fulfilling a “vow,” perhaps in support of Hannah’s earlier vow (v.11). Hannah decided not to make the trip this time. She preferred to wait until Samuel was weaned. Then she could leave him there to serve the Lord for the rest of his life, as she had promised. After Samuel’s weaning, Hannah intended to “present him before the LORD.” Elkanah agreed with his wife’s desire to follow through with her vow.

24–28 The big day finally arrived, and Hannah was ready. For the trip from Ramah to Shiloh, they took ample provisions. The three-year-old bull was doubtless meant to be sacrificed to the Lord. The purpose of the flour and wine remains obscure (cf. 28:24; Jdg 6:19). When the official slaughterers at the tabernacle had sacrificed the bull, Hannah and Elkanah brought Samuel before Eli the priest. In addressing Eli, Hannah used a common oath formula: “As surely as you live.” She thus solemnly affirms that she is indeed the same woman he first had met a few years earlier and that the boy, Samuel, given in answer to her prayers, is now to be given back to the Lord. Eli responded by worshiping the God whom they both served.

2. The Song of Hannah (2:1–11)

1–2 Verses 1–10 are commonly referred to as the “Song of Hannah” because of similarities to other ancient OT hymns (e.g., Ex 15:1–18, 21; Dt 32:1–43; Jdg 5; and esp. 2Sa 22). It may have originated as a song of triumph at the Shiloh sanctuary in connection with Israel’s victory over an enemy. Such songs would have been taught to worshipers, and this one perhaps became a personal favorite of Hannah. Therefore she sang it as a means of expressing her gratitude and praise to the Giver of life (cf. esp. v.5). Hannah’s song may have been the seedplot for Mary’s Magnificat (Lk 1:46–55; cf. also the Song of Zechariah in vv.68–79).

The song begins on a note of grateful exuberance: Her heart rejoices in the Lord—and in his “deliverance” (or “salvation”; GK 3802) as well (see Pss 9:14; 13:5; 35:9; Isa 25:9). The metaphor of one’s “horn” (GK 7967) being lifted high perhaps comes from the animal world, where members of the deer family use their antlers in playful or mortal combat. “Horn” thus symbolizes strength.

For Hannah, the Lord is holy, unique, and mighty. She therefore celebrates God’s holiness in righteous victory. She then connects his uniqueness with the metaphor of the Rock (cf. 2Sa 22:32; cf. also Ge 49:24; Dt 32:4; Isa 26:4; et al.)

3–8d After describing God’s majesty and power, Hannah warns all who would vaunt themselves in their pride (including Peninnah!). Arrogance is both foolish and futile (Pss 31:18; 75:4; 138:6). God judges the heart and weighs it rather than external appearances (cf. 16:7). The “broken” bows are echoed by the “shattered” opponents of v.10. Making the strong weak and the weak strong is what God does (cf. Heb 11:32–34).

The last half of v.5 had special meaning for Hannah, who had once been barren (cf. Jdg 13:2–3). “Seven” here means simply “many,” but at the same time also represents the ideal (cf. Job 1:2; 42:13). Just as she who has had many “pines away,” so the mother of seven will “grow faint.” The formerly barren Hannah eventually had a total of six children (v.21).

The Sovereign God ultimately blesses some and curses others (cf. vv.9c–10c). Verse 6a contrasts death with life; possibly the second half does too, though it may also refer to rescue from the brink of death after a serious illness (therefore contrasting sickness with health; cf. Ps 30:2–3).

The Lord can—and does—reverse the fortunes of poor and rich (Zec 9:3–4), of the humble and the proud (Job 5:11; Ps 75:7; and esp. 2Sa 22:28). He can lift a Baasha “from the dust” and later consume him (1Ki 16:2–3); he can ensconce a Job on an ash heap (Job 2:8) and later restore him (Job 42:10).

8e–10 The “foundations of the earth” (cf. 2Sa 22:16) refers pictorially to the firmness and stability of God’s creation—which is always under his sovereign control. How much more is he able to protect his people (Pr 3:26) and confound his (and their) enemies (Dt 32:35)!

The word often translated “saint” (GK 2883) means “one to whom the Lord has pledged his covenant love [GK 2876]” (cf. Pss 12:1, 8; 50:5, 16; 97:10; 145:10, 20). The final destiny of the ungodly, however, is the silence of Sheol, the “grave” (GK 8619; v.6), where all is darkness (Job 10:21–22; 17:13; 18:18; cf. also Mt 8:12).

Hannah learned that in the battles of life it is not physical strength that brings victory. Whether through human agency or directly, God always shatters the enemy (cf. Ex 15:6; Ps 2:9). Peninnah may have “thundered against” (1:6, lit.) Hannah, but Hannah knew full well that the Lord would ultimately “thunder against” Peninnah and all others who oppose him.

The Song of Hannah ends as it began, by using the word “horn” in the sense of “strength.” Hannah voices the divine promise of strength to the coming “king”—initially David, who will found a dynasty with messianic implications. The king—the “anointed” one (GK 5431)—will rule by virtue of God’s command and will therefore belong to him body and soul. The king will be “his” (2Sa 22:51).

11 With Samuel’s dedication and Hannah’s song complete, the family returned to Ramah—except for Samuel, who began what was to be a continuing ministry.

3. The wicked sons of Eli (2:12–26)

12–17 The reference to Hophni and Phinehas as “wicked men” (GK 1175) contrasts them with Hannah, who did not consider herself a “wicked woman” (1:16). Furthermore, the sons of Eli “had no regard for the LORD”—unlike Samuel, who “did not yet know” (3:7) the Lord.

Not content with the priests’ portions of the sacrificial animals (cf. Lev 7:34), the servant of Eli’s sons “would take for [themselves] whatever the fork brought up.” And not only that, “even before the fat was burned” (Lev 7:31), Hophni and Phinehas demanded raw meat. On occasion they even preferred roasted meat to boiled—as if in mockery of the necessarily hasty method of preparing the first Passover feast (Ex 12:8–11). They wanted their unlawful portion before the Lord received what was rightfully his. Their rebellion, impatience, and impudence were great sins. These premonarchic priests treated the Lord’s offerings with contempt, which could only lead to disaster (cf. Nu 16:30–32).

18–26 As a young apprentice priest under Eli’s supervision, Samuel wore the “linen ephod,” a priest’s garment. Indeed, the little “robe” that Samuel’s mother made for him annually as he was growing up may well have been an example of the “robe of the ephod” (Ex 28:31). By providing Hannah with additional children, the Lord continued to be gracious to her (cf. Ge 21:1). Samuel’s continued growth in the Lord’s presence, in stature and in favor with God and people, anticipates Luke’s portrayal of Jesus’ youth (Lk 2:40, 52).

The hapless Eli, whose advanced age is stressed from this point on (4:15, 18), was unable to restrain the sinful conduct of his sons. To their earlier callous treatment of their fellow Israelites (vv.13–16), they added sexual promiscuity—and with the women who served at the tabernacle (cf. Ex 38:8)! Such ritual prostitution was specifically forbidden to the people of God (Nu 25:1–5; Dt 23:17; Am 2:7–8). Eli’s rebuke, justified in the light of widespread and public reports of his sons’ evil deeds, fell on deaf ears. His theological arguments, weak at best, were to no avail, especially since God had already determined to put Hophni and Phinehas to death. What is eminently clear is that God’s decision to end the lives of Eli’s sons was irrevocable. Hannah had already expressed her willingness to leave such decisions within the sphere of divine sovereignty (v.6)—and so must we!

4. The oracle against the house of Eli (2:27–36)

27–36 The chapter concludes by expanding on the Lord’s intention to put Eli’s sons to death (v.25). The prophetic oracle to (and against) Eli uses the messenger formula (“This is what the LORD says”) and mediates the divine word through an anonymous “man of God.” The term “man of God” occasionally refers to an angel (cf. Jdg 13:3, 6, 8–9) but is usually a synonym for “prophet” (cf. 1Sa 9:9–10). This man of God reminds Eli that God had revealed himself to his ancestor Levi’s house (in Aaron; see Ex 4:14–16) before the Exodus. Indeed, Aaron had been the object of special divine election to serve the Lord as the first in a long line of priests (Ex 28:1–4). Aaron would go up “to” the Lord’s altar and would wear the ephod in the course of his divinely ordained work (cf. Lev 8:7).

Recipients of such privilege, Eli and his sons nevertheless “scorn” (GK 1246) the Lord’s prescribed sacrifices. Literally, the verb means “to kick” and is found only once elsewhere in the OT (Dt 32:15). Although the Hebrew words for “fat” and “heavy” are different there than the word for “fattening” here, the parallel is striking: Like Israel centuries earlier, the house of Eli has “kicked at” the Lord’s offerings by gorging themselves on the best parts of the sacrifices (vv.13–17). By condoning the sin of Hophni and Phinehas, Eli has demonstrated that he loves his sons more than he loves God and that he is therefore unworthy of the Lord’s continued blessing (see Mt 10:37).

The Lord had promised that Aaron’s descendants would always be priests (cf. Ex 29:9), and he had confirmed that promise on covenant oath (Nu 25:13). They would “minister [GK 2143] before” the Lord forever. But because of flagrant disobedience, the house of Eli would be judged by God. Although the Aaronic priesthood was perpetual, individual priests who sinned could thereby forfeit covenant blessing. The description of divine judgment, when translated literally, is vivid: “I will chop off your arm and the arm of your father’s house.” Furthermore, Eli would be the last “old man” in his family line, because God’s execution of his death sentence would be swift and sure (4:11, 18; 22:17–20; 1Ki 2:26–27).

Examples of the predicted distress in God’s “dwelling” (GK 5061; the tabernacle is meant) are the capture of the ark by the Philistines (4:11) and the destruction of Shiloh (cf. Jer 7:12, 14; 26:6, 9). Although in Eli’s line there would “never” be an old man, in the line that would replace his there would “always” be a faithful priest. The only member of Eli’s line to “be spared” was Abiathar, and he was later removed from the priesthood (1Ki 2:26–27).

Hophni and Phinehas would die “on the same day” (4:11), a prophetic sign to Eli not only of his own impending death but also of the fulfillment of the other components in the oracle of the man of God. The Lord would bring a “faithful” priest on the scene, who would be privy to the very thoughts of God and obedient to him.

“Faithful” (GK 586) contrasts strongly with the rebellion of Eli’s sons and plays an important role in the succeeding context, both near and remote. In this same verse the Lord says, “I will firmly [GK 586] establish his house”—lit., “I will build for him a faithful house” (cf. 2Sa 7:27). In the present context the faithful priest whose house the Lord would establish refers initially to Samuel (3:1; 7:9; 9:12–13; cf. esp. 3:20). Later, however, the line of Zadok would replace that of Abiathar, Eli’s descendant (2Sa 8:17; 15:24–29; 1Ki 2:35)—a replacement that would constitute a greater fulfillment of the oracle of the man of God. Zadok and his descendants would thus “always” minister before the Lord’s “anointed one”—David’s son Solomon (1Ki 2:27, 35) and his descendants. Ultimate fulfillment would come only in Jesus the Christ, the supremely Anointed One, “designated by God to be high priest” (Heb 5:10) “forever, in the order of Melchizedek” (6:20).

As for the members of Eli’s house, once fattened on priestly perquisites, soon not even the least benefit of priestly office would be theirs.

5. The call of Samuel (3:1–4:1a)

1 Special revelation was rare in the days of the judges. The few visions that did exist were not widely known (cf. Am 8:11–12). The word “vision” (GK 2606) means “divine revelation mediated through a seer.”

2 Eli’s aging eyes were so “weak” (cf. Dt 34:7) that he could barely “see” (he would eventually go completely blind; cf. 4:15). How different from Samuel, whose eyes saw clearly in a physical and a spiritual sense (v.15)!

3 The lamps on the seven-branched lampstand (Ex 25:31–37) were filled with olive oil, lit at twilight (30:8), and kept burning “before the LORD from evening till morning” (27:20–21; cf. Lev 24:2–4; 2Ch 13:11). Thus Samuel’s encounter with the Lord on his bed in the tabernacle compound took place during the night, since the “lamp of God had not yet gone out.”

4–10 Although Samuel did not yet know that it was the Lord who was speaking to him, his answer was typical of the servant who hears and obeys the divine call (Ge 22:1, 11; Ex 3:4; Isa 6:8). Samuel’s openness to serving God would soon enable him to know the Lord in a way that Eli’s sons never did (2:12). Although the word of the Lord had not yet been revealed to Samuel, that would soon take place (v.11); and as God continued to speak to Samuel through the years (v.21), the Lord’s word would so captivate him that it would be virtually indistinguishable from “Samuel’s word” (4:1). Samuel the priest would become Samuel the prophet (v.20).

Samuel thought that Eli was calling him. Twice Eli told Samuel to go back to bed, but the third time it finally dawned on the aged priest that it must be God who was calling the boy. He therefore told Samuel that he should respond the next time by saying, “Speak, LORD, for your servant is listening.” This time the Lord “came and stood there,” suggesting that Samuel could see him as well as hear him. Again the Lord called out Samuel’s name twice, imparting a sense of urgency and finality. Samuel responded as Eli had instructed, though he left out the word “LORD.”

11–14 The Lord’s word to Samuel not only had immediate reference to Eli’s house but also pointed forward to the more remote future (2:27–36). The disaster to overcome Eli and his sons (including the destruction of Shiloh) would “make the ears of everyone who hears of it tingle.” Death was the penalty for showing contempt for the priesthood (Dt 17:12) as well as for disobeying one’s parents (21:18–21), and Eli was implicated because he did not “restrain” (GK 3909) Hophni and Phinehas. The house of Eli had thus committed blatant sins against God and showed no signs of remorse. They were now subject to the divine death sentence (2:25; cf. Heb 12:16–17), and no sacrifice or offering could atone for their guilt.

15–18 When Samuel arose in the morning, he opened the doors of the tabernacle compound and doubtless busied himself with other tasks to avoid telling Eli what he had seen and heard. The aged priest was not to be denied, however, and demanded a full report. Indeed, he swore an oath of imprecation, calling down God’s judgment if the boy refused to tell everything he knew. Samuel’s obedient response in v.18 echoes key words from v.17 (pers. tr.): “Samuel told him all the words; he did not hide [anything] from him.” Eli’s reaction is both devout and submissive; he resigns himself to divine sovereignty.

3:19–4:1a As the Lord’s presence would later be with David (16:18; 18:12), so the Lord was with Samuel, a fact evident to all the Israelites. That God “let none of [Samuel’s] words fall” means that he made sure that everything Samuel said with divine authorization came true. Although earlier God’s word had not been revealed to Samuel (v.7), it now was; and as the Lord had appeared to him earlier (vv.10–14), so he “continued to appear at Shiloh.” The Lord’s word became equivalent to “Samuel’s word” (4:1; see comment on 3:4–10).

The focus of this section is thus the Lord’s sentence of judgment against the house of Eli. The boy Samuel, having become a “man of God” (9:6–14), has confirmed in no uncertain terms the prophecy earlier proclaimed by the anonymous “man of God” (2:27–36).

B. The Ark Narratives (4:1b–7:17)

1. The capture of the ark (4:1b–11)

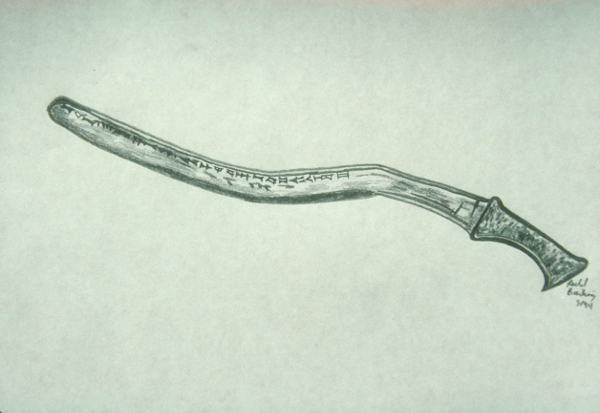

1b The “Philistines” (GK 7149), inveterate enemies of Israel, are mentioned nearly 150 times in 1 and 2 Samuel alone. They were so entrenched and dominant in the coastal areas and the foothills of Canaan that they eventually gave their name (Palestine) to the entire land. Although their connections with various Aegean cultures have been verified through decades of intensive research, their origins remain somewhat obscure. The OT relates them to Caphtor (Ge 10:14 = 1Ch 1:12; Jer 47:4; Am 9:7), which was probably Crete. The aggressive, expansionist ancestors of the Philistines of the time of Samuel apparently arrived in Canaan shortly after 1200 B.C.

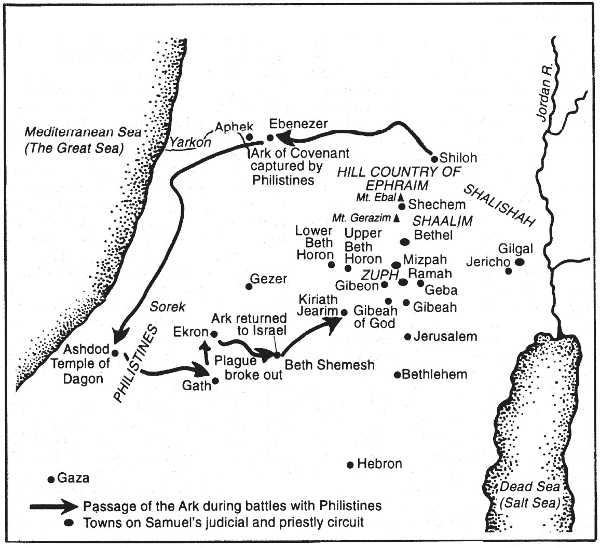

It is impossible to say who was the aggressor in this first-recorded battle between Israel and the Philistines. The Philistines camped at Aphek, an important site inhabited during the entire biblical period. Ebenezer, where the Israelites camped, is about two miles east of Aphek on the road to Shiloh.

2–3 The Israelites were defeated not once but twice in this chapter (vv.2, 10). Not until 7:10–11 did they defeat the Philistines on the battlefield and then only (as always) with divine help. The Israelites lost “four thousand” men, a terrible tragedy. The Israelite elders were puzzled by the debacle on the battlefield. Their solution was to bring the ark of the covenant into the camp to guarantee the Lord’s presence with his people. The “ark” (GK 778) is a significant thematic element in this section.

The elders doubtless remembered the account of Joshua’s victory over Jericho (Jos 6:2–20; cf. also Nu 10:35). What they failed to understand, however, was that the ark would not ensure victory. If God willed defeat for his people, a thousand arks would not bring success. The elders understood clearly that if God was not “with” them, defeat was inevitable (Nu 14:42; Dt 1:42). They mistakenly assumed, however, that wherever the ark was, the Lord was.

4–9 So men were sent to Shiloh from the Israelite camp at Ebenezer to bring back the ark, here impressively described as “the ark of the covenant of the LORD Almighty, who is enthroned between the cherubim” (cf. 2Sa 6:2; 2Ki 19:15). In ancient Near Eastern art a king was often pictured sitting on a throne supported on each side by a cherub (winged lions with human heads.) One function of the ark of the covenant was to serve as the symbolic cherub-throne of the invisible Great King.

The ark, accompanied by Hophni and Phinehas, caused a great commotion upon reaching the Israelite camp. The people gave a loud shout (cf. Jos 6:5, 20). The uproar aroused the Philistines camped nearby, and their superstitious response echoed that of the Israelite elders. They believed that the arrival of the ark heralded the coming of whatever god or gods its owners worshiped. To avoid being enslaved by the Hebrews, as the Hebrews had been by them (cf. Jdg 13:1), they encouraged one another to be strong and fight like men.

10–11 The result of the ark’s presence was another Israelite defeat, this one far more severe and described as a “slaughter” (GK 4804). The Philistines’ own turn would come (14:13; 19:8; 23:5), but in the meantime Israel suffered heavy losses. The sins of Eli’s sons produced appalling casualties among Israel’s foot soldiers (cf. Dt 28:15, 25). As foretold by the man of God (2:34), Hophni and Phinehas died. The elders’ folly was revealed as the Philistines captured the ark, and the destruction of Shiloh—and perhaps the tabernacle itself—was not far behind.

2. The death of Eli (4:12–22)

12–18 No sooner was the second battle with the Philistines over than the tragic news of Israel’s defeat reached Shiloh. A Benjamite messenger, with his clothes “torn and dust on his head” (cf. Jos 7:6; Ne 9:1), reports Israel’s flight from and slaughter by the Philistines as well as the death of two prominent priests.

Eli is sitting on his chair beside the road (cf. 1:9). Perhaps no longer considering himself to be the priest he once was, he nevertheless trembles with fear for the ark’s safety.

The messenger first told his story to the townspeople at Shiloh, who “sent up a cry” when they learned that the ark had not brought them victory and was no longer with them. Mere possession of the ark enabled neither Israelite nor Philistine to manipulate the God whose presence it symbolized.

Hearing the uproar in the city, Eli wanted to know its meaning. Ninety-eight years old, obese, and totally blind, Eli was probably unable to go into town without considerable help; so the messenger went to him. The news was bad indeed. That his sons were dead did not seem to faze Eli, who may have already given them up as hopeless. But the shock of hearing that the ark had been captured was too much for him. He “fell” off his chair, broke his neck, and died. The tragedy of Eli’s life matches that of Saul: sometimes serving God faithfully, at other times not measuring up to even the most moderate of standards. Priest at Shiloh for most of his adult life, Eli had judged Israel forty years.

19–22 Eli’s death did not end the tragedy, even in his own family. The message of Eli’s and Phinehas’s deaths, combined with the report of the ark’s capture, caused Phinehas’s pregnant wife to go into premature labor. The distressing report caused her to be “overcome by her labor pains.” The combination was fatal: She died in childbirth. Before she died Phinehas’s wife named her newborn son Ichabod (“No glory”; cf. 14:3): “The glory [GK 3883] has departed [lit., ‘has gone into exile’] from Israel, for the ark of God has been captured.” After the Exodus the Lord promised to consecrate the tabernacle by his glory (Ex 29:43); after it was set up, his glory filled it and the cloud covered it (Ex 40:34–35). “Glory” represents the Presence of God dwelling in the tabernacle (Ps 26:8; cf. also Ex 25:8; 29:44–46), giving rise to the later theological term the “Shek(h)inah Glory” (cf. also Heb 9:5). Perhaps the wife of Phinehas, in her dying hour, spoke better than she knew.

3. The Lord’s affliction of the Philistines (5:1–12)

1–5 From the battlefield at Ebenezer, the Philistines took the ark to Ashdod, apparently the chief city (6:17). Ashdod was located three miles from the Mediterranean coast about thirty miles southwest of Ebenezer. The ark was brought into the temple of Dagon, the Philistine national deity, and placed near a large idol representing him. The next day the statue of Dagon had fallen facedown, vanquished by Israel’s God (see 17:49) and lying prostrate before the ark in a posture of worship. The people of Ashdod put the idol back in its “place” (cf. v.11).

The next morning Dagon was again facedown before the ark—this time with its head and hands “broken off” (cf. 17:51). In the ancient world severed heads and hands (cf. Jdg 8:6) were battlefield trophies. The Lord had therefore vanquished Dagon in his own temple. The head and hands of Dagon’s statue landed on the temple threshold, rendering it sacred (in the minds of his worshipers) and therefore untouchable (cf. Zep 1:4, 9).

6–12 With the reference to Dagon’s hands being rendered helpless, a major motif is introduced in the account: “the LORD’s hand.” The first reference here to the hand of the Lord comes from the lips of the Philistines, who related the divine hand to the plagues of Egypt (4:8)—and rightly so (see Ex 9:3; cf. also Jer 21:5–6). They did not take lightly the possibility that the fate of the Egyptians might befall them also (6:6).

“Tumors” (GK 6754) were one of the many potential curses that would be inflicted on the Israelites if they disobeyed God (Dt 28:58–60). Here that affliction descended on the Philistines, who realized that the hand of the Lord was heavy on them (cf. v.11). Their five rulers (6:18) advised them to get rid of the ark—which all recognized as the visible counterpart for the Israelite deity and therefore the cause of the plague—by moving it to Gath (about twelve miles east-southeast of Ashdod). The Lord’s hand was then against Gath (cf. 7:13) and brought “an outbreak of tumors” on its inhabitants.

The ark was quickly shipped to Ekron (about six miles due north of Gath). But the arrival of the ark in Ekron had the same effect there as the news of its capture had in Shiloh: The people sent up a cry for help, fearful that the God of Israel would “kill” them—a power that he certainly possessed (cf. 2:6, 25). The people of Ekron told their rulers to send the ark away. Even those who did not die were afflicted with tumors; no one escaped the dreaded plague.

4. The return of the ark (6:1–7:1)

1–6 Chapter 4 tells of the capture of the ark, ch. 5 of its movement from place to place in Philistia, and ch. 6 of its return to Israel after being in Philistine territory for several months. The Philistines, eager to rid themselves of the ark and its sinister influence, sought supernatural guidance as to the best way of sending the ark back to “its [proper] place.” “Tell us how,” they said to their pagan counselors.

Ancient religious protocol mandated that the worshiper not approach his god(s) empty-handed (cf. Ex 23:15; Dt 16:16). Thus the Philistine priests and diviners advised that a guilt offering accompany the ark back to Israel. Although such an offering was normally an animal sacrifice, occasionally money or other valuables were acceptable. If the Lord accepted the Philistines’ offering, their people would be healed; then they would know that his hand had been responsible for their misery.

The linking of tumors, rats, and plague suggests that the tumors were symptoms of bubonic plague spread by an infestation of rats, which were capable of destroying a country (cf. Jer 36:29; Da 11:16). The Philistine advisers recommended gold models of tumors and rats to serve as the guilt offering to placate the God of Israel. Perhaps the Philistines intended the models to function in the realm of sympathetic magic also, so that by sending them out of their land the genuine articles would depart as well.

The word “plague” (GK 4487) recalls the Egyptian plagues in Ex 9:14, further heightening the parallel between the earlier disaster and this (cf. again v.6). The lesson is clear: Hardening one’s heart only brings divine retribution, resulting in the victory of God’s people over their enemies (Ex 12:31–32). The Philistines are thus well advised to cut their losses as soon as possible.

7–12 A new cart pulled by two cows “that have calved and have never been yoked” was to be used to transport the ark. The cows would later be sacrificed by the Israelites (v.14) in faint reminiscence of the slaughter of the red heifer by Eleazar (Nu 19:2–3). The Philistines were to “take” the calves from their mothers, “send” the gold objects as a guilt offering to the Lord, and “return” the ark to him and his people (v.21).

The first destination of the ark was Beth Shemesh, just inside Israelite territory. Beth Shemesh had a pagan past (its name means “Temple of the sun-god”). The Philistines of Samuel’s day acknowledged that Beth Shemesh was under Israelite control. They hoped that the cows would take the ark there, reasoning that if cows new to the yoke would desert their newborn calves—even temporarily—to pull a cart all the way to Beth Shemesh, that would be a supernatural sign that the divine owner of the ark had sent the plague against them. But if the ark did not reach Beth Shemesh, they would take that fact as proof that the Lord’s hand had not struck them and that mere chance was responsible.

Against natural instinct (“lowing all the way” because their calves were not with them) and under divine compulsion (not turning “to the right or to the left”—i.e., staying on the main road), the cows pulled the cart straight to Beth Shemesh. The five Philistine rulers, following the cows to the border, stayed only long enough to make sure that the ark was securely in Israelite hands.

6:13–7:1 The ark arrived at Beth Shemesh in June, during wheat harvest, after the spring rains (cf. 12:16–18). Rejoicing to see the ark, the people decided to use the cart for fuel and to sacrifice the cows as a burnt offering. They “chopped up the wood” (cf. Ge 22:3). A large rock in a field belonging to Joshua of Beth Shemesh became the temporary locale for the ark. The Levites, who alone were permitted to handle the ark (cf. Jos 3:3; 2Sa 15:24), had removed it from the cart and set it on the rock, which served as a witness of the ark’s homecoming.

Meanwhile, the five Philistine rulers returned to their five cities (cf. Jos 13:3). Each one was fortified and was supported by a number of nearby “country villages” (cf. similarly Dt 3:5; Est 9:19).

Divine retribution continued to overtake those who misused the ark. This time some men of Beth Shemesh “looked into” (GK 8011) the ark, a sin punishable by instant death (Nu 4:5, 20; cf. also 2Sa 6:6–7). The mourners sensed that the ark symbolized the presence of a “holy God” (cf. Lev 11:44–45), whose sanctity they could not approach. They therefore hoped he would depart from them.

Kiriath Jearim (about ten miles northeast of Beth Shemesh) was the ark’s location for the next twenty years (7:2). More specifically, it resided at “Abinadab’s house on the hill” (7:1; 2Sa 6:3). Eleazar son of Abinadab was then consecrated to guard it. The downgraded status of the ark may have been partially due to the Philistine destruction of Shiloh (presupposed by Ps 78:60; Jer 7:12, 14; 26:6, 9) and perhaps the tabernacle as well. Not until David’s accession as king in Jerusalem would the ark once again be restored to its rightful place of honor (2Sa 6).

5. Samuel the judge (7:2–17)

2–4 The “twenty years” that the ark remained at Kiriath Jearim may be figurative for “half a generation,” during which time the “people” (lit., “house”; GK 1074) of Israel “mourned,” apparently with sincere remorse. They were bemoaning the reduced status of the ark, no longer housed in a tabernacle. Samuel encouraged them to repent and to serve the Lord wholeheartedly, as he would do later (12:20, 24).

Samuel urged the people to get rid of the foreign gods (GK 466; cf. “the Baals and the Ashtoreths” in 12:10) that they were so prone to worship (cf. also Dt 12:3; Jdg 10:16; 2Ch 19:3; 33:15). Baal and Ashtoreth were the chief god and goddess in the Canaanite pantheon during this period. Samuel pleaded with them to commit themselves wholeheartedly to the Lord. God’s people are to serve him exclusively (see Dt 6:13).

5–6 The assembly of “all Israel” did not necessarily include every single Israelite living in the land but most likely consisted of representatives from all the tribal territories. Convocations at Mizpah in Benjamin were not uncommon in the days of the judges and early monarchy (cf. 10:17; Jdg 20:1; 21:8). There Samuel prayed for the people (cf. also vv.8–9; 8:6; 12:19, 23; 15:11; Jer 15:1), and there they “poured . . . out [water] before the LORD,” perhaps a symbol of contrition (cf. 2Sa 23:16).

The notice of Samuel’s judgeship is followed immediately by a report of Philistine intention to attack Israel. The function of a “judge” during this period was more executive than judicial. “Judge” often paralleled “ruler” or “prince” (cf. Ex 2:14), and one of the most common roles of the judge was to repel invaders (Jdg 2:16, 18).

7–9 Cowed by Philistine might, Israel typically reacted with fear to news of impending warfare with them (17:11; 28:5). But when the Philistines “came up” to attack, Samuel prayerfully “offered . . . up” a burnt offering to the Lord. The sacrifice was a suckling lamb at least eight days old (cf. Lev 22:27).

10–12 While the sacrifice was still in progress, the Philistine troops marched forward. Before the battle could be joined, however, the Lord “thundered” against the enemy (see 2:10; 2Sa 22:14–15). He demonstrated that he, not the Philistine Dagon, not the Canaanite Baal son of Dagon, was truly the God of the storm, the only one able to control the elements whether for good or ill (cf. 12:17–18). “With loud thunder” highlights the vivid OT image of thunder as the voice of God (see Ps 29:3–9).

The ensuing panic in their ranks (cf. 2Sa 22:14–15) drove the Philistines into full retreat, enabling the Israelites to pursue and slaughter them. The Ebenezer of v.12 is almost certainly not the Ebenezer of 4:1 and 5:1, since the latter is too far to the northwest for Mizpah to be used as a benchmark for its location. Ebenezer (“The stone of [divine] help”), the stone set up by Samuel, paid tribute to the God apart from whom victory is inconceivable (cf. Ge 35:14; Jos 4:9; 24:26).

13–17 The second half of v.13 assumes continued Philistine pressure (though greatly reduced) against Israel and thus cautions us not to understand the first half as meaning that the Philistines no longer bothered the Israelites (cf. esp. 9:16). The Amorites, who preferred to live in the hilly regions of the land (cf. Nu 13:29; Dt 1:7) as compared to the Philistines who lived along the coast, were also relatively nonbelligerent during this period.

The circuit of Samuel’s judgeship was relatively restricted: Bethel, Gilgal, and Mizpah were all within a few miles of one another. All three towns served as shrine centers at one time or another, as did Ramah, Samuel’s hometown. The latter was not far from the other three (about fourteen miles northwest of Mizpah). The local nature of judgeship in ancient Israel subtly introduces us to the need for a king.

II. Advent of Monarchy in Israel (8:1–15:35)

Monarchy was a significant factor in God’s plans for his people from the days of Abraham (Ge 17:6, 16). The blessing of Jacob hints at the establishment of a continuing dynasty (Ge 49:10). Israel was to be “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex 19:6). Balaam’s fourth oracle refers to monarchical rule (Nu 24:17–19), and Moses outlines the divine expectations Israel’s kings were to meet (Dt 17:14–20).

However, from the earliest days it was recognized that ultimately God himself was King (Ex 15:18; Nu 23:21; Dt 33:5); he alone possessed absolute power and authority (Ex 15:6, 11; Jdg 5:3–5). Any king of Israel would have to appreciate from the outset that he was to rule over Israel under God. Only on the basis of this fundamental theological premise can the narratives of the advent of monarchy in Israel be properly understood.

A. The Rise of Saul (8:1–12:25)

1. The demand for a king (8:1–22)

1–3 With reference to Samuel’s advanced age (vv.1, 5; 12:2), the old order (of the judges) is passing, the new (of the monarchy) is dawning. While Samuel continued as judge at Ramah and nearby towns (7:15–17), he appointed his two sons to serve in the same capacity at Beersheba on the southern boundary of the land (cf. 3:20). Their actions and reputations (v.5) belied their names—Joel (“The Lord is God”); Abijah (“My [Divine] Father is the Lord”)—but at least their geographical distance from Samuel (Beersheba is about fifty-seven miles south-southwest of Ramah) absolved him from any direct complicity in their evil deeds.

Whether Samuel should have appointed his sons as judges in the first place is highly questionable, since judgeship was usually a divine charisma. In any event, they did not follow in their father’s footsteps. “Turned aside” and “perverted” (both GK 5742) tie their three sins together. Failing to emulate their father (12:3–4) or their God (Dt 10:17), Joel and Abijah accepted bribes, a crime inseparable from the perversion and denial of justice (Pr 17:23). Ironically, Samuel’s two sons were as wicked in their own way as were Eli’s two sons.

4–9 Old men (“elders”) confront the old man and—perhaps unwittingly—remind him of the cruel parallel between himself and the deceased Eli (cf. 2:22). Because of Samuel’s age, and because they want nothing to do with a dynastic succession that would include his rebellious sons, the elders decide that a king would best suit their needs. Samuel had “appointed” his sons as “judges”; the elders wanted him to “appoint” (GK 8492) a king to “judge” Israel.

This king was to lead them, “such as all the other nations have.” Verse 20 reveals their hidden agenda: The king would “go out before us and fight our battles.” They were looking for a permanent military leader who would build a standing army powerful enough to repulse any invader (cf. Dt 17:14, 15–17). Samuel, fully aware of those dangers, was “displeased” with the elders’ request—and he was convinced that the Lord too was displeased (12:17; cf. also 15:11).

But Samuel, as he sought God’s mind in the matter, was doubtless surprised when the Lord told him to “listen to” (or “obey”; GK 9048) the people’s request mediated through their elders. Israel was not rejecting the Lord’s chosen leader but the Lord himself (see also 10:19). Since the days of the Exodus, the people had consistently preferred other gods and other leaders to God himself and his chosen servants.

God, graciously condescending to the people’s desire (a desire not in itself wrong but sullied by the motivation behind it), told Samuel to warn them what the “regulations of the kingship” (10:25) would demand of them, particularly their loss of freedom in (absolute) monarchy.

10–18 The “regulations of the kingship” described by Samuel (with God’s prompting and approval) were totally bereft of redeeming features and consisted only of oppressive requirements. Among the latter was forced labor, including compulsory induction of both raw recruits and laborers in field and foundry.

The palace-to-be would acquire horses in great numbers (cf. Dt 17:16), and the king’s chariots would need front runners (cf. 2Sa 15:1; 1Ki 1:5). Reference to commanders “of thousands and . . . of fifties” implies a huge standing army, with “weapons of war.” Women would not be exempt from conscription into royal service. Even in desperate times the king would always get his share (Am 7:1)—a minimum of 10 percent of the income from field and flock.

Key words in the “regulations of the kingship” are “take” (GK 4374) and “best” (GK 3203). By nature royalty is parasitic rather than giving, and kings are never satisfied with the worst. Samuel’s regulations followed contemporary semifeudal Canaanite society. In the light of Samuel’s own record of fairness and honesty during his judgeship (cf. esp. 12:3–5), it is no wonder that he was alarmed at the prospect of setting up a typical Oriental monarchy in Israel.

If these “regulations of the kingship” attained full authority, the average Israelite would soon be little more than a chattel at the disposal of his monarch. The frequent occurrence of “servant” and “slave” thus sounds an especially ominous note. In v.17 Samuel warned the people that they would “become” their king’s “slaves” (GK 6269), terminology employed elsewhere of bondage imposed by a conqueror (17:9). Too late the Israelites would cry out to a God who would not answer—unlike the days when Samuel was judge (7:8–9).

19–22 Samuel’s best efforts were futile. Despite his totally negative delineation of the royal “regulations,” the people refused to “listen to” (or “obey”; GK 9048) him. They wanted a king—a demand that Samuel hurled back in their teeth twice in the context of their rejection of divine rule (10:19; 12:12). They clung doggedly to their original request (v.5). The implicit military component of their idea of monarchy now becomes explicit: Their king would “fight our battles”—although a godly Israelite king would know from the outset that it was the Lord’s joyful duty to do just that for his people (2Ch 32:8).

As the Lord had told Samuel earlier (v.7), so he told him now: “Listen to them and give them a king.” On that negative (for Samuel) note the chapter ends, and Samuel’s farewell oration to Israel begins (12:1).

2. The anointing of Saul (9:1–10:16)

1–2 Saul’s father, Kish, is called a “man of standing” (cf. Ru 2:1; 1Ki 11:28). The term often has military connotations and is translated “brave man” in Saul’s servant’s description of David (16:18). It is nowhere used of Saul himself. The family line of Kish is from Benjamin, the smallest of the tribes. Israel’s first king came from these humble origins. The Hebrew root for the name “Saul,” which means “Asked (of God),” occurs in 8:10, where the people were “asking” for a king (GK 8626).

Saul is introduced as an “impressive” young man (cf. Ge 39:6; 2Sa 14:25), “without equal” among the Israelites. That would eventually change, however; his kingdom would be torn from him and given to “one better than” he—to David (15:28). Saul was also “a head taller” than his fellow Israelites, a characteristic noteworthy enough to be mentioned again (10:23–24). Of regal stature, he had the potential of being every inch a king. Saul’s subsequent failure as king makes the well-known divine admonition in 16:7 all the more poignant.

3–14 The Lord used straying donkeys to bring Saul into contact with Samuel. Searching for the lost donkeys, Saul and his servant crisscrossed the borderlands between Benjamin and Ephraim, but to no avail. They began and ended their search in the “hill country of Ephraim” since Zuph is associated with the hill country in 1:1. The unnamed town in v.6 is therefore probably Ramah.

Saul, not wishing to cause his father needless worry, wants to give up the search and return to Benjamin. The servant, however, points out that there is a “man of God” nearby who might be able to help them. The servant appears to be more persistent and imaginative than Saul himself—a fact that may not speak well for Saul’s future attempts at leadership. Although the man of God is not named at first, we are later informed that he is indeed Samuel.

Saul continued to protest, reminding the servant that they had no gift for the prophet; their “sacks” were empty. When consulting a prophet, it was common courtesy to bring a gift (Am 7:12), whether modest (1Ki 14:3) or lavish (2Ki 8:8–9). The servant responded that he had “a quarter of a shekel of silver” to give to the prophet. Although coinage was not invented until the seventh century B.C., it is likely that much earlier there were pieces of silver of fixed weight.

Verses 9–10 bring together the three main terms to describe the prophetic office: “seer” (GK 8014), “prophet” (GK 5566), “man of God” (GK 408 & 466). Samuel is often (and fittingly) called the “last of the judges and first of the prophets”—the latter in the sense that the formal office of prophet began with the monarchy and ended shortly after the monarchy did (for Samuel’s unique role, cf. 2Ch 35:18; Ps 99:6; Jer 15:1; and esp. Ac 3:24; 13:20; Heb 11:32).

“Seer” means just what its Hebrew (and English) root implies: one who sees—but with spiritual eyes—beneath the surface of the obvious, focusing on the divine dimension. A seer was a man of (spiritual) vision (cf. Isa 1:1; 6:1–5; Jer 1:11–19; Am 7:7–9; 8:1–2; Zec 1:7–6:8).

A “prophet” was “called” in the sense of being summoned by God to be a spokesman for God (cf. Ex 4:16; 7:1–2). A prophet was to be God’s “mouth”; that was his “calling.” Prophecy was by calling, not by choice.

Saul and his servant went “up the hill” to the town (probably Ramah, which means “height”). It was early evening, since girls were coming out to the well to draw water (see Ge 24:11; cf. also v.19). When asked whether the seer was there, they informed the men that he had arrived only recently to participate in a sacrificial ritual at the “high place.” Almost always on conspicuous elevations and often located outside of town (vv.14, 25), high places were open-air sanctuaries, sometimes with shrines or other buildings (v.22), where worship was conducted. The association of high places with idolatry had contributed to the divine rejection of Shiloh and the capture of the ark (Ps 78:58–61).

Verses 12–13 are charged with urgency: “He’s ahead of you. Hurry now; he has just come. . . . Go up now.”

15–24 The divine encounter with Saul was mediated through Samuel, to whom the Lord had “revealed" (lit., “uncovered the ear of," as if to speak in secret) his will (cf. 2Sa 7:27; 1Ch 17:25). As an act of gracious condescension to the people’s request (Ac 13:21), the Lord promised to send an obscure Benjamite to Samuel, emphasizing the divine initiative in the matter. Samuel was to “anoint" him (with oil; cf. 10:1; cf. also 15:1, 17).

Anointing was by prophet and/or people, both acting as agents of the Lord (cf. 16:12–13; 2Sa 2:4; 5:3). It symbolized the coming of the Holy Spirit in power (16:13; Isa 61:1–3). Especially at the beginning of the monarchy, anointing was to the office of “leader” (GK 5592) rather than “king” (cf. 10:1; 13:14; 25:30; 2Sa 5:2; 6:21; 7:8). Beyond the likelihood that it represents Samuel’s understandable reluctance to establish a full-fledged kingship (with all its negative implications; cf. again 8:10–18), the term might have been a title for “king-designate, king-elect” (cf. 2Ch 11:22) with military connotations.

In language strongly reminiscent of the Exodus, God had looked on the people of Israel (cf. Ex 2:25), whose cry had reached him (cf. Ex 3:9). The new leader would have the potential of delivering Israel from the Philistines (cf. 4:3)—although some seriously doubted that Saul would be able to accomplish that formidable task (10:27).

The seer Samuel “caught sight of” Saul, raised up as leader because God had “looked upon” his people. “This is the man,” the Lord said to him, in a scene that would be replayed with only modest variations a few years later (cf. 16:12). Samuel then identified himself to Saul. As the Lord had promised to “send” Saul to Samuel, so Samuel would soon “let” Saul “go” (lit., “send” him on his way, as in v.26) after his divine commissioning (10:9). Samuel the seer authenticated his prophetic role by revealing Saul’s inmost thoughts and relieved Saul’s mind by informing him that his father’s donkeys had been found. He then told Saul that all Israel was eagerly awaiting his benevolent reign.

Saul respectfully demurred. He pointed out that Benjamin, his tribe, was the smallest in all Israel (doubtless due to the terrible massacre decades earlier; cf. Jdg 20:46–48) and that his clan was the weakest in his tribe (cf. Jdg 6:15). Saul’s humility (cf. 10:22) was in the grand tradition of prophets and judges.

Samuel, however, knowing that Saul was God’s choice, brushed aside his objections and led him and his servant into a “hall” (GK 4384), in a building on the high place outside Ramah. This Hebrew word almost always denotes a room in a sanctuary or temple. Such rooms were normally used as apartments for sanctuary personnel or as storerooms (cf. Ne 10:39; Jer 35:2, 4). The hall at Ramah was large enough to seat thirty people.

Saul and his servant, guests of honor, were seated at the head of the table. The special “piece of meat” brought to Saul was perhaps the “share” of the sacrifice normally reserved for priests (cf. Lev 7:33). It was a special “occasion” (GK 4595) indeed, a time for celebration—unlike a future “set time” (13:8, 11) when Saul’s impatience and disobedience would initiate his downfall (13:13–14).

25–27 After what must have been a sumptuous if solemn meal, eaten in a house of worship on a sacred site, Samuel, Saul, and Saul’s servant retired to Ramah and conversed for a while on the “roof” of Samuel’s house. Samuel was preparing Saul for his divine commissioning as ruler of Israel. Sleeping overnight on the roof of a house is a common practice even today in the Middle East. The following morning Samuel told Saul to dismiss his servant temporarily (see 10:14). Saul himself, however, was to stay briefly at Ramah (10:2) to receive a communication from God and to be anointed leader over the Lord’s inheritance (10:1).

10:1–8 Saul’s rise to kingship took place in three distinct stages: He was (1) anointed by Samuel (9:1–10:16), (2) chosen by lot (10:17–27), and (3) confirmed by public acclamation (11:1–15). The Lord had told Samuel to anoint Saul as leader over his people Israel (9:16). Samuel now proceeded to fulfill that command, being careful to inform Saul that the anointing was from the Lord. The Israelites are here called the Lord’s “inheritance” (GK 5709) in the sense that they inhabited his territorial patrimony and belonged uniquely to him as Creator, Redeemer, and Conqueror (Dt 4:20; 9:26; 32:8–9; Ps 78:70–71). The anointing oil was a distinctive formula (Ex 30:23–33); it was “sacred” (Ps 89:20). Samuel also kissed Saul as an act of respect and submission (cf. Ps 2:11–12).

Verses 7 and 9 speak of three “signs” (GK 253) that would confirm the Lord’s choice of Saul. (1) Samuel said that Saul would “meet” two men who would verify that Kish’s donkeys had indeed been found and that therefore Saul’s father could now devote his attention to his son’s welfare. (2) Three men would meet Saul and offer him two loaves of bread, which he would accept. The men were “going up to God” to worship and commune with him. On their way they would “greet” Saul. (3) This sign, because of its significance, is described at greater length. Whereas the first sign involved two men and the second involved three men, the third focused on a “procession”—a larger band or group—of prophets (vv.5, 10). Saul would meet them outside “Gibeah of God.”

The beginnings of the Israelite monarchy witnessed the emergence of a prophetic movement known as the “sons of the prophets” (cf. 1Ki 20:35). “Sons” is used here in the sense of “members of a group” (cf. 2Ki 2:3, 5, 7, 15). The companies were often large in number (“fifty,” 2Ki 2:7; “one hundred,” 1Ki 18:4, 13; 2Ki 4:43). They were frequently associated with time-honored places, such as Ramah (19:18–20), Bethel (2Ki 2:3), Jericho (2:5), and Gilgal (4:38). Their characteristic activity was “prophesying,” usually interpreted to mean “uttering ecstatic praises/oracles.” The actions and activities of prophetic bands were sometimes accompanied by music (2Ki 3:15; 1Ch 25:1–7).

Individual or group prophesying was often induced when the Spirit of the Lord came on a person in power (19:20, 23; Nu 11:25, 29). At such times the prophet would experience an altered state of consciousness and would be “changed into a different person” (cf. also v.9). Such ecstasy was often contagious (19:20–24). Similar ecstatic phenomena, though in a negative sense, were sometimes induced when an “evil” or “injurious” spirit came on a person (18:10; cf. also 16:14–16, 23). Members of prophetic bands were often young (2Ki 5:22; 9:4); they frequently lived together (2Ki 6:1–2), ate together (2Ki 4:38), and were supported by the generosity of their fellow Israelites (2Ki 4:42–43). Samuel provided guidance and direction for the movement in its early stages. At the head of a particular group of prophets would be the “father” (2Ki 2:12) or “leader” (19:20).

Samuel told Saul that after the three signs were fulfilled, he was to do whatever his hand found to do (cf. Ecc 9:10). Samuel assured Saul that God was with him, implying that therefore he could not fail (cf. Jos 1:5).

Then came a sober warning: At a later time Samuel would meet Saul at Gilgal. A preliminary meeting would first be held there to reaffirm Saul’s kingship (11:14–15), with the appropriate fellowship offerings and accompanying celebration. Then on a later occasion Samuel would meet Saul again at Gilgal, this time to sacrifice burnt offerings (cf. Lev 1:3–17; 6:8–13) and fellowship offerings (cf. Lev 3:1–17; 7:11–21). On this latter occasion Saul was to wait seven days, until Samuel came and told him what to do. Saul faithfully fulfilled the former obligation (13:8), but impatience got the better of him. He failed to await Samuel’s arrival with further instructions, and his act of disobedience was the beginning of the end for his kingdom (13:9–14).

9–16 Meanwhile, however, Saul was open to Samuel’s instructions and the Lord’s leading. He “turned” to leave, and as he did so, God “changed Saul’s heart” (cf. the third sign; v.6). The arrival of Saul and his servant at Gibeah of God (cf. v.5) was followed by the Spirit of God coming on Saul in power, resulting in his joining the prophetic band in their ecstatic behavior (cf. 11:6).

Gibeah of God was scarcely four miles northeast of Gibeah of Saul, the hometown of the new Israelite ruler. When his fellow townsmen learned of Saul’s arrival, they turned out in force to see what had happened to the “son of Kish.” The Spirit of the Lord, coming on Saul in power, authenticated him as Israel’s next ruler and produced the visible evidences of ecstatic behavior. To question the genuineness of that behavior was to question Saul’s legitimacy in his new office.

“And who is their father?” was asked to find out the identity of the leader of the “procession of prophets” (cf. 2Ki 2:12). Although perhaps prompted by the reference to Saul as “son of Kish,” the question was not so banal as to be requesting information about Saul’s physical paternity.

Verses 14–16 conclude the theme of Kish’s concern for Saul’s whereabouts and welfare. Saul’s “uncle” was doubtless seeking information for Kish and himself. The story of finding Kish’s lost donkeys is once again related, but Saul did not tell his uncle anything about Samuel’s view of kingship or his own participation in it (cf. 8:6–22). Rule over Israel would soon be his in truth (11:14), but it would not be long before he would be convinced that he was about to lose it to a man after God’s own heart (18:8).

3. The choice of Saul by lot (10:17–27)

17–24 Assembling the Israelites at Mizpah, Samuel addresses them in words strongly reminiscent of those of the prophet in Jdg 6:8–9a. The Lord is called the God of his chosen people Israel. He then speaks in the first person, using the emphatic pronoun “I” in strong contrast to the emphatic “But you.” The familiar Exodus redemption formula is followed by a reminder that God had delivered his people not only from Egypt but also from the “kingdoms” that “oppressed” them. Although the Lord had saved them out of all their “calamities and distresses,” they had rejected him (echoing 8:7; cf. also Nu 11:20). The Israelites continued to insist in no uncertain terms that they wanted a king (see 8:5, 19). Samuel, reluctantly acquiescing, told the people to present themselves before the Lord by their tribes and clans.

The lots, known as Urim (“Curses,” providing negative responses) and Thummim (“Perfections,” providing positive responses), were stored in the breastplate attached to the ephod of the high priest (Ex 28:28–30) and were brought out and cast whenever a simple “yes” or “no” would suffice. Although casting lots was perhaps not unlike throwing dice, God himself guided the results (Pr 16:33). Verses 20–21 show that Benjamin was chosen by lot from the Twelve Tribes, Matri (unknown elsewhere) from the Benjamite clans, and Saul—God’s man for this season—from the Matrite families. Ironically, like the lost donkeys that had earlier consumed so much anxious time for their searchers (9:3–5, 20; 10:2, 14–16), “when they looked for [Saul], he was not to be found.”

Another divine oracle was therefore necessary, but this time the question demanded more than a “yes” or “no” answer. So in a more direct way the people “inquired” (GK 928 & 8626) of the Lord to discover Saul’s whereabouts. The reluctant “leader” was subsequently found hiding among the military supplies (cf. 17:22; 25:13; 30:24).

Anxious to hail their new king, the people ran to bring him out from his hiding place. He came out and presented himself in their midst; his impressive height is again stressed (9:2). Samuel reminded the Israelites that the Lord had “chosen” (GK 4334) Saul.

The public acclamation “Long live the king!” represents now, as it did then, the enthusiastic hopes of the citizenry that their monarch would remain hale and hearty in order to bring their fondest dreams to fruition. The people of Saul’s day “shouted” their approval.

25–27 After the people’s acclamation of Saul as their king, Samuel outlined for them the “regulations of the kingship,” which he then wrote down on a scroll (cf. Ex 17:14; Jos 18:9). He deposited the scroll in a safe place “before the LORD”—i.e., in the tabernacle, probably located at Mizpah at that time (cf. v.17)—in order (1) to preserve it for future reference and (2) to have it serve as a witness against the king and/or people, should its provisions ever be violated (cf. Dt 31:26; Jos 24:26–27).

Samuel then permitted all the people to return to their homes. Saul, the recently anointed king, went to his home in Gibeah. With the formal festivities over, two opposing reactions to Israel’s new leader surface: “Valiant men,” apparently eager to affirm God’s choice, accompanied Saul to Gibeah, while “troublemakers” despised him. The latter group unwittingly echoed to Saul the earlier words of Gideon about himself: “How can I save Israel?” (Jdg 6:15). Neither Gideon nor the troublemakers understood—at least not at first—that it is God, not a human being, who saves (Jdg 6:16; 1Sa 10:19).

4. The defeat of the Ammonites (11:1–11)

1–2 The Ammonite siege of Jabesh Gilead under Nahash produced a conciliatory response in its inhabitants. They asked Nahash to “make a treaty” with them, as a result of which they would recognize him as their suzerain and become his vassals (cf. Eze 17:13–14). The phrase “cut a covenant” is almost universally understood to refer to the sacrifice (“cutting”) of one or more animals as an important element in covenant solemnization ceremonies in ancient times. Nahash’s threat to gouge out the right eye of every Jabeshite may imply their rebellion against a previously established overlordship. In the ancient Near East, the physical mutilation, dismemberment, or death of an animal or human victim could be expected as the inevitable penalty for treaty violation.

3 Nahash’s threat (v.2) received a plaintive response from the elders of Jabesh, who functioned as representatives of the community (cf. 4:3; 8:4; 16:4). They tried to buy some time to send for help. Nahash appears to have acceded to the elders’ request, apparently sure of his own military superiority.

4 When the Jabeshite messengers arrived at Gibeah of Saul with the terms of Nahash’s demands, its people “wept aloud,” a common display of grief, distress, or remorse (cf. Jdg 2:4; 1Sa 24:16; 2Sa 3:32; 13:36). Apparently Saul’s fellow citizens in his own hometown despaired of leadership at this critical juncture in their history.

5–6 But at that very moment, Saul was returning from plowing in the fields, and he asked two questions: “What is wrong with the people? Why are they weeping?” Upon hearing the Jabeshites’ report, Saul was energized by a powerful accession of God’s Spirit. He had already experienced a similar accession earlier (10:6–10). This time, in the tradition of the judges, the Spirit of God filled him with divine indignation and empowered him as a military leader. Although the earlier accession had been temporary, this one was somewhat more permanent, apparently lasting until Samuel anointed David to replace Saul as king (16:13–14).

7 Rallying the troops to defend a covenant suzerain, vassal, or brother was a common stipulation in ancient treaties. Similar to the earlier action of the Levite of Jdg 19:29; 20:6, Saul cut two of his oxen into pieces and sent them throughout Israel as a graphic illustration of what would happen to any tribe that failed to commit a contingent of troops (cf. Jdg 21:5, 10). The “terror of the LORD” that here fell on the people is not to be understood as fear of divine punishment.

8 The mustering or counting of the troops (cf. 13:15; 14:17; 2Sa 24:2, 4) took place at Bezek. The numbers represent substantial contingents of troops. Their being listed separately as “men of Israel” and “men of Judah” anticipates the eventual division of the kingdom into north and south.

9 Saul and his troops told the messengers to return to Jabesh Gilead and inform its frightened citizens that divine deliverance (cf. v.13) would come to them the very next day—“by the time the sun is hot” (cf. Ex 16:21; Neh 7:3), a phrase that almost surely refers to high noon. The messengers’ report caused the men of Jabesh to become “elated” (cf. v.15).

10 Confident of victory, the Jabeshites promised the Ammonites that they would surrender to them the following day and that the Ammonites would then be free to do “whatever seems good to you” (lit., “whatever seems good in your eyes,” an ironic pun on Nahash’s earlier threat to gouge out the right eye of any rebellious Jabeshite; cf. 14:36).

11 Saul wasted no time in deploying “his men” for the attack on Ammon. “The next day” probably refers to the evening of the day on which Saul’s message reached the Jabeshites (v.9), since among the Israelites each new day began after sunset. Saul, following a military strategy common in those days (see 13:17–18), divided his men into three groups. Offensively it gave the troops more options and greater mobility, while defensively it lessened the possibility of losing everyone to a surprise enemy attack. The Israelites under Saul’s leadership broke into the Ammonite camp “during the last watch of the night” (cf. Ex 14:24). Saul’s attack obviously caught the Ammonites by surprise, and—as promised (v.9)—by high noon God had defeated them and delivered his people, routing the enemy survivors by scattering them in every direction (cf. also Nu 10:35; Ps 68:1).

5. The confirmation of Saul as king (11:12–12:25)

12–15 Saul’s troops and the people of Jabesh Gilead, having witnessed God’s victory over Ammon under Saul’s leadership, demanded from Samuel the death penalty for all the troublemakers who had questioned his ability to save them from foreign rule (10:27). Saul, however, showing how magnanimous he could be when given the opportunity, asserted that the divine deliverance was a cause for gratitude, not vengeful retribution (cf. 2Sa 19:22).

Saul’s demonstration of the leadership qualities necessary to be Israel’s king led Samuel to convoke an important meeting at Gilgal. The OT records three meetings of Samuel and Saul at Gilgal, each fateful for Saul: (1) In the flush of his victory over Ammon, Saul was reaffirmed as king (11:14–15); (2) because of his impatience while awaiting Samuel’s arrival, Saul was rebuked by his spiritual mentor (13:7–14); and (3) because of his disobedient pride after the defeat of the Amalekites, Saul was rejected as king (15:10–26).