INTRODUCTION

See the introduction to 1 Samuel.

EXPOSITION

I. Consolidation of Monarchy in Israel (1:1–20:26)

The overriding theme of the books of Samuel is the beginning of Israel’s monarchy in the eleventh century B.C. Having discussed its prelude (1Sa 1:1–7:17), advent (1Sa 8:1–15:35), and establishment (1Sa 16:1–31:13), the author next turns to its consolidation under David, Israel’s greatest king.

A. David’s Accession to Kingship Over Judah (1:1–3:5)

The story of David’s rise to the kingship begins with an account of the decimation of Saul’s line (1:1–16) and ends with a summary of David’s fecundity (3:2–5). Nestled in the center of this literary unit is the narrative of David’s anointing as king over Judah (2:1–7), signaling the replacement of Saul and his house in southern Canaan.

1. The death of Saul and Jonathan (1:1–16)

Second Samuel begins as 1 Samuel ends—with an account of the death of King Saul and his son Jonathan, the heir apparent. But while 1Sa 31 describes the events as they occurred, 2Sa 1:1–16 consists of a report of the events filtered through the not disinterested words of an Amalekite.

1–5 Saul’s defeat and death at the hands of the Philistines and David’s victory over the Amalekites occurred at approximately the same time. The distance from Mount Gilboa to Ziklag is more than eighty miles, a three-day trip for the Amalekite fugitive. Torn clothes (cf. v.11) and dust on one’s head are signs of anguish and distress, appropriate and understandable behavior in a man who has so recently witnessed a battlefield scene of suffering and death. The man demonstrates his submission to David by prostrating himself.

David’s desire to know where the man has come from is doubtless prompted by the man’s appearance. His response—that he has escaped from the Israelite camp—makes David all the more curious; so he demands that the man tell him what has happened. His report reveals that the Israelites “fled” (GK 5674) from the battle against the Philistines and that many of them died. What is more, continues the man—who obviously thinks that he is bringing David good news (4:10)—“Saul and his son Jonathan are dead.” David of course wants to know how the messenger can be so sure of this latter assertion; so the man tells his story.

6–10 The Amalekite’s account deviates in several important respects from that in 1Sa 31. Most of the proposed solutions to the problem only serve to further complicate it. On Mount Gilboa (the scene of Saul’s last battle, 1Sa 31:1), the Amalekite encountered the wounded Saul, who was supporting himself by “leaning on his spear.” Seeing the Amalekite nearby, Saul called out to him. The man replied with the response commonly used by servants: “What can I do?” Perhaps to be sure that the man was not a Philistine, who might abuse the Israelite king if he had the chance (cf. 1Sa 31:4), Saul asked the man to identify himself.

Satisfied as to the general identity of the young man, Saul uttered words reminiscent of the earlier description of David’s dispatching of Goliath: “Stand over me and kill me” (cf. 1Sa 17:51). Although in mortal agony and wanting to die, Saul seemed unable to take his own life. Apparently happy to oblige, the Amalekite claims to have fulfilled Saul’s wish to the letter. He “knew” that the fallen king could not survive, and—since he himself had killed him—he could also “know” for certain that Saul was dead. After killing the king, the Amalekite took Saul’s “crown,” the primary symbol of his royal authority (cf. 2Ki 11:12), as well as a band that he was wearing on his arm.

11–12 Having once been a valued member of Saul’s court, David undoubtedly recognizes the crown and armlet. But the messenger could scarcely have been prepared for the response of David and his men, who tear their clothes with heartfelt expressions of grief over Saul and Jonathan and mourn and weep. They also fast, but only “till evening,” which was apparently David’s usual practice in such situations (cf. 3:35). Their sorrow extends to the people as a whole, since all Israel has suffered tragic and irreparable loss in the death of their king.

13–14 Apparently after the period of mourning is over, David questions the messenger again. David wants to know something of the man’s background. The man affirms that, in addition to being an Amalekite, he is the son of an “alien.” David has now learned all that he needs to know concerning the man. Since his father was a resident alien, living in Saul’s realm, the young man can be expected to have at least minimal knowledge about Israel’s basic traditions, including the inviolability of “the LORD’s anointed.” By the Amalekite’s own testimony, he had destroyed the Lord’s anointed king, something David had never done (see 1Sa 24:6, 10; 26:9, 11).

15–16 Far from receiving the reward that he thinks David will surely give him because of the “good news” he thought he was bringing (cf. 4:10), the Amalekite’s callous bravado has sealed his own doom. David has the young man executed with the words, “Your blood be on your own head” (cf. 1Ki 2:31–33). In the light of 1Sa 31, it is clear that the young man’s claim to have killed Saul was false, however much the rest of his story may appear to have the ring of truth.

2. David’s lament for Saul and Jonathan (1:17–27)

17–18 That David was the author of this remarkable poem about 1000 B.C. is universally recognized. The poem is strikingly secular, never once mentioning God’s name or elements of Israel’s faith. Like Joshua’s poetic address to the sun and moon (Jos 10:12–13), this lament was eventually written down in the “Book of Jashar” (a poetic collection no longer extant).

19 “Mighty” is probably best understood as being parallel to “glory,” and thus “slain” is parallel to “fallen.” “Heights” here refers to Gilboa, located in “Israel,” which was Saul’s main realm and to whose people David’s lament is addressed. Not yet king over all Israel, David orders that the lament be taught only to the men of “Judah” (v.18), where he has already gained considerable influence.

20 The verb translated “proclaim” (GK 1413) almost always implies good news—in this case, of course, only from the standpoint of the Philistines. “Gath,” on the eastern edge of Philistine territory, and “Ashkelon,” by the sea, represent all of Philistine territory. The “daughters of the Philistines/uncircumcised” will rejoice at this news, in contrast to the “daughters of Israel,” who must “weep for Saul” (v.24).

21 This verse consists of a curse on the “mountains of Gilboa,” the site of the Israelite defeat (cf. Ps 106:38; Hos 4:2–3). In Hebrew thought, “dew” was often a symbol of resurrection or the renewing of life (cf. Ps 110:3; Isa 26:19). Regarding Saul’s shield being “defiled” (GK 1718), the text is unclear as to whether the Philistines treated Saul’s shield as they wished or whether it was “rejected (with loathing)” in the sense that the shield is pictured as lying on the mountains, worthless and neglected, no longer oiled and ready for action.

22–23 Each verse refers to both Saul and Jonathan by name, the only verses in the lament to do so. They summarize the bravery, the determination, the comradeship, and the ability of the two men. Jonathan’s “bow” did not turn back from “blood,” and Saul’s “sword” did not return (to its sheath) “unsatisfied” from “flesh” (cf. Dt 32:42; Isa 34:5–6).

The Hebrew word order of v.23 suggests that the king and his son, inseparable in life as in death, would continue to be honored in death as in life.

24 Verse 24 mirrors v.20 (see comment). Here David calls on the “daughters of Israel” to “weep” (GK 1134) for Saul, as he and all his men had done (v.12). Weeping for/over a person was a universal custom in ancient Israel (3:34; Job 30:25; et al.). The “daughters” are probably wealthy women of the land since Saul has lavished fine clothes and expensive jewelry on them.

25–26 “How the mighty have fallen” is a verbatim echo of v.19 and at first gives the impression that the lament concludes at this point. The addition of “in battle,” however, signals that v.25 is a false ending. The two lines of v.25 reverse the elements of v.19, its mirror image.

David’s grief is for Jonathan, his “brother” (GK 278)—not in the sense of “brother-in-law” (a true enough description; cf. 1Sa 18:27) but of “treaty/covenant brother.” David’s further statement that Jonathan’s “love” (GK 173) for him was “more wonderful than that of women” should be understood to have covenantal connotations (i.e., covenantal/political loyalty; translated “friendship” in Ps 109:4–5).

27 The song ends as it began, with the central theme of “How the mighty have fallen!” David’s lament for Saul and Jonathan is characterized by both passion and restraint. While giving full vent to his feelings on hearing the report of their death, David displays no bitterness toward his mortal enemy Saul. Since in v.18 David orders that the men of Judah be “taught” his lament, apparently the epic hymns of Israel’s history were intended to be taught and applied from generation to generation. David’s lament may well have been a favorite.

3. David anointed king over Judah (2:1–7)

1–4a Now that King Saul is dead and buried, the time has come for the private anointing of David (1Sa 16:13) to be reprised in public. David decides to leave Ziklag (1:1)—but not without seeking divine guidance. Unlike Saul, David “inquired of the LORD,” doubtless by asking his friend Abiathar the priest to consult the Urim and Thummim stored in the ephod that he had brought with him from Nob (1Sa 22:20; 23:6; cf. 23:1–4, 9–12; 30:7–8).

David wants to know whether he should “go up” to one of the towns in the hill country of Judah. By means of the sacred lots, the Lord responds affirmatively. When David then asks for a more precise destination, the lots pinpoint Hebron as the place. Located twenty-seven miles northeast of Ziklag, Hebron was the most important city David sent plunder to after defeating the Amalekites (1Sa 30:31) and looms large in chs. 2–5. Obedient to the divine command, David severs his ties with Philistine Ziklag and, with his two wives Ahinoam and Abigail (27:3; 30:5), moves to Judahite Hebron. He also takes with him the army of men who have rallied to his leadership, and they together with their families settle in Hebron and its nearby villages. David is publicly anointed by the “men of Judah” as king over Judah. David’s elevation to kingship, however, is fundamentally due to divine anointing (1Sa 16).

4b–7 Word eventually reaches David that the men of Jabesh Gilead had given Saul a decent burial. Since Jabesh is an Israelite (not Judahite) town and therefore presumably still loyal to Saul’s house, David realizes that he must try to win them over to his side. He therefore sends messengers to them with overtures of peace and friendship, an approach that stands in sharp contrast to the tactics used by David’s men in the rest of the chapter.

The Jabeshites are commended for “showing kindness” (in the sense of demonstrating loyalty) to Saul. “Kindness” (GK 2876) of this sort ultimately derives from God, as David himself recognizes (cf. 9:1, 3, 7). Indeed, he invokes the Lord’s “kindness and faithfulness [GK 622]” on the Jabeshites. Both of these are part of all genuine covenant relationships, and David stresses his eagerness to transfer the Jabeshites’ covenant loyalty from Saul to himself. He offers to show them the same favor that Saul had shown them. He reminds them that Saul their master is now dead and that the house of Judah has anointed him as king. He concludes his offer by encouraging them to “be strong and brave.” But there is more than one fly in the ointment, as the rest of the chapter clearly suggests.

4. War between Saul’s house and David’s house (2:8–3:1)

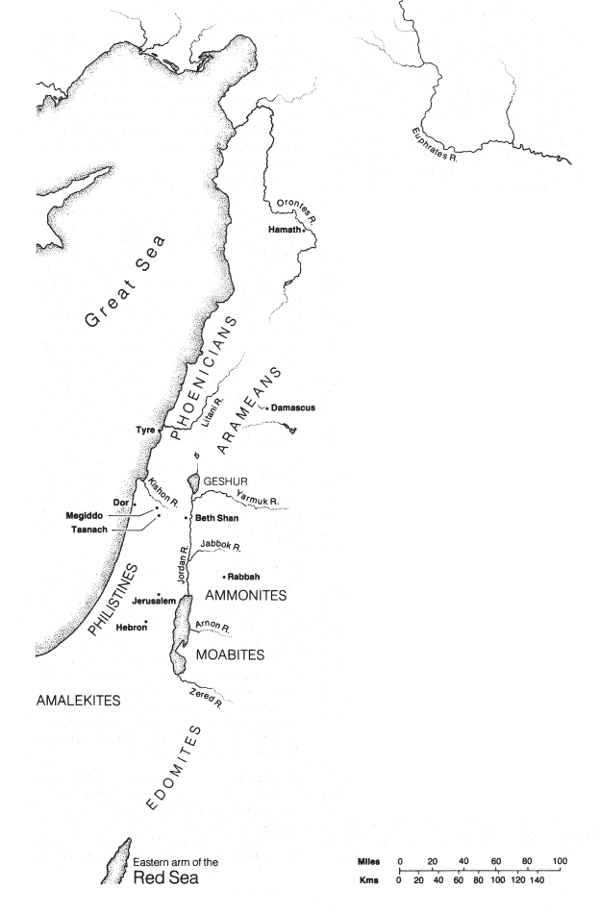

2:8–11 Abner, Saul’s cousin and the commander of Saul’s army (cf. 1Sa 14:50; 17:55; 26:5), had either avoided or escaped from the battle on Mount Gilboa that had resulted in the death of Saul and his three sons (1Sa 31:8). Still ostensibly loyal to the dead king, he had taken a fourth son, Ish-Bosheth, and brought him to Mahanaim, far away from the continuing Philistine threat. Located just north of the Jabbok River in the tribal territory of Gad (Jos 13:26, 30; 21:38), it would later serve as a place of refuge for David during the rebellion of Absalom (17:24, 27; 19:32; 1Ki 2:8).

Ish-Bosheth (“Man of shame”), mentioned only in chs. 2–4, is perhaps to be identified with Ishvi in 1Sa 14:49. Not killed in Saul’s last battle (cf. 1Sa 31:2), he may have been something of a coward. Scribal tradition often substituted the word bosheth (“shame”; cf. GK 1017) for the hated name of the Canaanite god Baal (cf. Jer 3:24). Thus Ish-Bosheth’s real name was E/Ish-Baal, “Man of Baal” (cf. 1Ch 8:33), Mephibosheth’s (4:4) was Merib-Baal (1Ch 8:34), and Jerub-Besheth’s was Jerub-Baal (11:21; cf. Jdg 6:32). Since baal is also a common noun meaning “lord” or “master” and could therefore be used occasionally in reference to the one true God (cf. Hos 2:16), Saul presumably did not intend to honor the Canaanite god Baal when he named his son Ish-Baal (which would mean “The man of the Lord”)—especially since the name of his firstborn son Jonathan means “The LORD has given.”

Although David became king over “the house of Judah” by popular anointing (v.4), Abner single-handedly makes Ish-Bosheth king over “all Israel,” thus demonstrating that he is the real power behind the throne of Israel now that Saul is dead. Gilead was located thirteen miles north of Mahanaim, indicating something of the difficulty David faced in attempting to win the Jabeshites over to his side. The territories of Ephraim and Benjamin are probably selected to represent those areas within Israel that could be reasonably considered to have been under Saul’s control (“all Israel” is an obvious hyperbole for the northern tribes). Ephraim was the largest tribal territory in the north, and Benjamin was the homeland of Saul (1Sa 9:1–2). It is this realm that Ish-Bosheth now inherits—with the ambitious Abner son of Ner pulling the strings.

While Ish-Bosheth was reigning over Israel, the tribe of Judah “followed David.” Since David is the man after God’s own heart, following David implies following the Lord.

David became king of all Israel shortly after Ish-Bosheth’s death (4:12–5:3). Because David’s reign in Hebron was more than five years longer than Ish-Bosheth’s in Mahanaim (2:10–11; cf. 5:5), it must have been several years after Saul’s death before Ish-Bosheth had gained enough support to become king over the northern tribes. Thus Ish-Bosheth’s two-year reign would have coincided with the last two years of David’s seven-and-one-half-year reign over Judah.

12–17 David and Ish-Bosheth each attempted to seize the other’s kingdom. Full-scale warfare was not the only way to accomplish such a goal, however. It could be done between teams of champions. Saul’s cousin Abner, together with Ish-Bosheth’s men, meet David’s nephew Joab, together with David’s men, at the “pool of Gibeon.” Once again the hand of God can be seen working on David’s behalf.

Ish-Bosheth’s men and David’s men sit down on opposite sides of the pool of Gibeon, probably facing each other. Abner makes a proposal, which Joab accepts, that some of the young men in one group “fight hand to hand” with some in the other. Twelve from each group are “counted off.” The number twelve here doubtless stands for the twelve tribes of “all Israel,” whose fate hangs in the balance. The initial skirmish ends quickly. Each man “grabbed” his opponent by the head, thrusting a dagger into his side. Just as all the men had met at the pool “together,” so also all the men now fall down “together.” Following that was a fierce battle, ending in the defeat of Abner’s men.

18–23 Asahel, one of the three “sons of Zeruiah,” is compared to a gazelle, though his speed as a runner would eventually prove to be his undoing (cf. v.23). The initial combat between Ish-Bosheth’s men and David’s men broadens and becomes more dangerous. Abner, not spoiling for a fight and eager to get out of harm’s way, flees the scene of the massacre. Asahel, however, is determined to overtake and kill Abner, nothing deterring him. After identifying his pursuer to his own satisfaction, Abner tells Asahel to give up the chase; he advises him to appease his desire for vengeance by killing one of the young men fleeing from Gibeon. The single-minded Asahel, however, is adamant.

Abner then issues a final warning: Unless he stops chasing Abner, Asahel will be the one who dies. Why would he want Abner to strike him “down”? And if Abner kills Asahel, how could he “look” Asahel’s brother Joab “in the face”? Abner’s fear of Joab proves to be not unfounded (cf. 3:27, 30). Asahel, however, refuses to listen. Continuing to run full speed ahead, he closes the gap between himself and Abner, and the latter suddenly turns to face his pursuer. Asahel’s momentum hurls him onto the butt of the spear of Abner, who thrusts it through Asahel’s “stomach” (cf. 3:27; 4:6; 20:10), killing him on the spot. As David’s men began passing by that place, they stood transfixed in horror at the death of a fallen comrade.

Asahel, though dead because of his headlong pursuit of Abner, would be long remembered in Israel. He is listed first among the Thirty, David’s military elite (23:24). It would only be a matter of time, however, before Asahel’s brother Joab would avenge his great loss (3:30).

24–28 Although others came to a halt at the sight of their dead comrade, Joab and Abishai (Asahel’s brothers) continue their pursuit of Abner. At sunset they come face to face with the Israelites (“the men of Benjamin,” since they probably formed the largest number as the tribe of Saul), who take their stand “on top of a hill”—an ideal vantage point from which to direct or engage in battle if necessary (cf. Ex 17:9–10). Just as Abner had earlier proposed that hostilities begin (v.14), so he now proposes that they cease with the words: “Must the sword devour forever? . . . How long before you order your men to stop pursuing their brothers?”

"How long” commonly introduces questions implying a rebuke. Abner cleverly baits Joab by referring to the two groups of antagonists as “brothers”—and Joab bites by accepting the identification. When brothers fight brothers, the result can only be “bitterness” and shame (Ob 10). Joab thus calls off the chase, and Abner’s timely plea thus leads to results remarkably similar to those described in 1Sa 25:34.

29 It was customary for armies to travel at night, probably to be as inconspicuous as possible. Marching eastward across the Jordan, Abner and his men continue until they arrive at Mahanaim.

30–32 Including Asahel, a total of twenty of David’s men are “missing” in action, presumably all dead. The body count of Ish-Bosheth’s men, however, is “three hundred and sixty.” The eighteen-to-one ratio in favor of David demonstrates how terrible was the cost of Abner’s arrogance (v.14) and how thoroughly “Abner and the men of Israel were defeated by David’s men” (v.17).

Joab’s men took Asahel’s body to Bethlehem, the hometown of David and his clan, where Asahel would be given a proper burial in “his father’s tomb.” During much of ancient Israelite history, multiple burials in family tombs cut into the underlying rock of the slopes of hills were commonplace. Having left the body of their fallen comrade in Bethlehem, Joab and his men continue on to Hebron, more than twenty miles southwest.

3:1 The “house of Saul” and the “house of David” figure prominently in the next several chapters (cf. esp. ch. 7). War—almost inevitable when rivals aspire to the same throne—continues between them “a long time” (at least for the two years of Ish-Bosheth’s reign over Israel). But Ish-Bosheth’s weakness is no match for David’s strength, and the outcome is a foregone conclusion.

5. Sons born to David in Hebron (3:2–5)

2–5 Anointed king over Judah in Hebron, David settled down with his two wives Ahinoam and Abigail and began to build a substantial family during his seven-and-a-half-year rule there. His firstborn son Amnon (“Faithful”), the son of Ahinoam, would ultimately be killed by the men of Absalom (13:28–29), David’s third son. His second son, Kileab, whose mother was Abigail, is mentioned only here and apparently died before he was able to enter the fray to determine who would be David’s successor as king of Israel.

Absalom (“[Divine] Father of peace”) was the son of Maacah, a Geshurite princess whom David may have married as part of a diplomatic agreement with Talmai, the Geshurite king. See chs. 13–18 for the story of Absalom.

Adonijah (“My Lord is the LORD”) the son of Haggith would figure prominently in the struggle for David’s throne (cf. 1Ki 1–2), eventually to be assassinated in favor of Solomon. David’s polygamy, begun with Ahinoam and Abigail (1Sa 25:43), continues unabated—indeed, it increases—in Hebron.

B. David’s Accession to Kingship Over Israel (3:6–5:16)

1. Abner’s defection to David (3:6–21)

The devastating defeat of Ish-Bosheth’s men by David’s men (2:30–31) has made its impact on Saul’s cousin Abner. Ruthless and ambitious, Abner is a canny politician who sees the handwriting on the wall. He therefore sets about to transfer Ish-Bosheth’s kingdom over to David—and Ish-Bosheth can only sit by helplessly and watch the inevitable unfold (vv.9–11). Doubtless hoping for a prominent place in David’s kingdom, Abner wants to be the divinely chosen agent in delivering Israel to David’s rule.

6 Abner is not only well positioned to wrest Israel’s kingdom from the hapless Ish-Bosheth but also to do with it whatever he pleases—including delivering it to David. While Abner was “strengthening his own position,” it was characteristic of David that he “found strength” in the Lord his God (1Sa 30:6).

7–11 Ish-Bosheth’s surprise question to Abner—“Why did you sleep with my father’s concubine?” (i.e., Rizpah)—arrives like a bolt from the blue. This act by Abner is probably intended to assert his claim to Saul’s throne (cf. vv.8–10; 16:20–22; 1Ki 1:1–4; 2:13–22). Abner responds indignantly to Ish-Bosheth: “Am I a dog’s head—on Judah’s side?” That is, how can Ish-Bosheth possibly think that Abner would defect to Judah? He protests that although he is loyal to Saul’s house, Ish-Bosheth is accusing him “now.” He has not, after all, handed Ish-Bosheth over to David. He therefore pretends not to be able to understand how Ish-Bosheth can “accuse” him of cohabiting with Rizpah.

Far from denying Ish-Bosheth’s accusation, however, Abner takes a strong oath of self-imprecation, vowing that he will become God’s instrument in bringing about what the Lord had promised to David—namely, transferring the entire kingdom of Israel to David. Cowardly and powerless, Ish-Bosheth can do nothing to stem the tide of Abner’s ambitions.

12–16 The preliminary meeting between Abner and David takes place through messengers rather than face to face. Abner’s rhetorical question, “Whose land is it?” is perhaps intentionally ambiguous. To Abner it means, “The land of Israel is mine to give” (and therefore David should make an agreement “with me”)—though it could also mean, “The land of Israel is yours because of God’s promise.” In any case, the Lord is working behind the scenes to deliver the northern tribes into David’s hands.

For his part, David is willing to accept Abner’s proposal only on one condition: that he bring Michal, Saul’s younger daughter, with him when he comes to Hebron. David is adamant, warning Abner not to come without bringing Michal.

David chooses his words carefully. When speaking to Abner he refers to Michal as “daughter of Saul,” thus reminding Abner that if he agrees to bring her with him he has turned his back on Ish-Bosheth for good and has assented to David’s succession to Saul’s throne. When speaking to Ish-Bosheth, however, David calls Michal “my wife,” thus reminding Ish-Bosheth that she is David’s wife (cf. 1Sa 18:25–27) and that the responsibility for her being now with Paltiel is Ish-Bosheth’s, since he is the son and heir of Saul, who wrongfully gave her to Paltiel in the first place (1Sa 25:44). Now that Saul’s death has given him a free hand, David wants to strengthen his claim to Saul’s throne by retrieving Michal.

The guardian and brother of Michal, Ish-Bosheth, powerless as ever, readily consents to David’s demand and takes Michal away from her husband Paltiel. When Abner and Michal depart for Hebron, the heartsick and weeping Paltiel tags along as far as Bahurim, where Abner orders him to go back home. And so it is that Michal is added to David’s roster of wives.

17–21 The time when Abner “conferred” with Israel’s elders was probably before the events of vv.15–16. Abner’s counsel to the elders is straightforward: There is no reason to delay any longer in making David king over all Israel. God had promised David that he would be divinely endowed to “rescue my people Israel from the hand of the Philistines,” a word originally spoken concerning Saul (see 1Sa 9:16). In any event, God himself is the true Deliverer of his people (cf. esp. 1Sa 7:8) and thus sovereignly chooses whom and when he will.

On his way to Hebron, Abner pays special attention to the Benjamites, Ish-Bosheth’s kinsmen, and tells them of his plans. He then went on and told David what Israel and Benjamin wanted to do. Though counted among the northern tribes and an indispensable part of the kingdom of Israel, the “house of Benjamin” would eventually become inextricably linked to the house of Judah (cf. 1Ki 12:21–23).

Arriving in Hebron with Michal, Abner and his twenty men sit down to a feast prepared for them by David. With his offer to bring “all Israel” into a covenant relationship with David, Abner’s defection to the house of Judah is complete. The agreement between the two men in vv.12–13 was personal and is not to be confused with the national “compact” now being made between north and south. Abner assures David that the end result of the compact would be that “you may/will rule over all that your heart desires” (1Ki 11:37). Abner’s mission now complete, David sends him away and he goes “in peace” (GK 8934).

2. The murder of Abner (3:22–39)

22–27 In the middle of this otherwise tranquil scene the narrator states that David’s men and Joab return from a raid. Arriving in Hebron and learning that Abner has come and gone, Joab goes to David and demands to know why he released Abner—the only genuine obstacle to David’s sitting on Israel’s throne—when he had him firmly in his grasp. After all, Abner is a cousin of Saul, who must therefore be an opponent of David. Indeed, to Joab, Abner has doubtless come to Hebron for the sole purpose of learning everything that might well prove useful in the future. Joab’s accusation that David allowed Abner to “deceive” him is ironic in light of his own subsequent treachery (cf. Pr 24:28–29).

David is realistic enough to recognize that he is still too weak to risk a showdown with the sons of Zeruiah (v.39). The brash Joab thus feels free to leave David without so much as waiting for a response to his rebuke; nor is David told that Joab’s men pursue Abner and bring him back.

Pretending that he wants to discuss a private matter with him, Joab takes Abner into a relatively secluded area. Then, “to avenge” (GK 928) the blood of his brother Asahel, Joab kills Abner. The method used is the same used in Abner’s killing of Asahel and thus illustrates the principle of retaliation in kind.

28 Upon hearing of Abner’s murder, David declares himself and his kingdom “innocent” (GK 5929) of all personal responsibility for Abner’s death. The motif of innocence is first recorded in the assessment of his friend Jonathan (1Sa 19:5; cf. also Pss 19:13; 26:6; 64:4). Needless to say, that opinion is not shared by disaffected Israelites, who hold David accountable for the massacre of the Saulides and continue to think of him as a “man of blood” (cf. 16:7–8).

29 David places the blame for Abner’s death squarely where it belongs by cursing the “head of Joab” and devoutly hoping that Abner’s blood will “fall” upon it—i.e., that Joab’s bloodguilt will eventually bring about his own destruction through divine vengeance (cf. v.39). Just as David had absolved himself and his “kingdom” of all guilt in the matter (v.28), so also now he includes Joab’s “father’s house” in Joab’s condemnation. In pronouncing this curse, David uses colorful language. He pleads that Joab’s house will never be without people who would suffer in five categories: (1) has a “running sore”; (2) has “leprosy”; (3) “leans on a crutch”; (4) falls by the sword; and (5) lacks food. The first three curses relate to physical ailments, the fourth to war, and the fifth to famine.

30 Since the blood of a kinsman was to be avenged by the death of the one who had shed it, Joab and Abishai invoked the hoary custom of the blood feud as a rationale for murdering Abner. It is, however, questionable whether the blood vengeance of Joab and Abishai was justified, seeing that Abner had killed Asahel in battle. Indeed, David later excoriates Joab for having shed the blood of Abner “in peacetime as if in battle” (1Ki 2:5). Joab, of course, may have had an ulterior motive in wanting Abner out of the way, for Abner could supersede him as commander of David’s army (8:16; 20:23; 1Ki 1:19; 11:15, 21).

31–35 David issues commands concerning Abner’s funeral: The murderer Joab is required to attend, as are all his men. David’s weeping and mourning over a slain family member, comrade, or friend is not only a concession to custom but also—and far more significantly—an indication of his tender heart (cf. 1:12; 13:36–37; 18:33; 19:1–4). Joab and his men walk in front of the funeral procession; David brings up the rear. Expressing his grief, the king “wept aloud” at Abner’s tomb.

The rhetorical question that begins the lament requires a negative answer. With his hands not bound and his feet not fettered, Abner was surely not “lawless.” Just as with Saul and Jonathan and their comrades in arms, David fasts till evening (see 1:12). Try as they might, Joab’s men are unable to induce David to eat the customary funeral meal (cf. Jer 16:5, 7). Although David could not have been completely unhappy about the death of his most powerful rival for control, his grief is genuine.

36–37 David’s magnanimity impresses Joab’s men and is sure to draw them ever closer to his inner circle of advisors. Indeed, in their eyes he can do no wrong. David was not an accessory to Abner’s death. His protestation of innocence, believable then to his own cohorts, is ratified now by the northern tribes.

38–39 The chapter concludes with David’s final brief encomium for Abner and final imprecation against Joab and Abishai, both of which are directed to his own men. Just as it was important for all Israel to know that David was innocent of the death of Abner (v.37), so also David wants his men to “realize” that in Abner a great man has been lost to Israel.

David realizes that although he is “the anointed king,” he is nevertheless “weak.” By contrast Joab and Abishai are “strong”; and David, exercising commendable caution, realizes that he is not presently able to rebuke them with any semblance of authority. In the hearing of his own men, however, he repeats the curse against Joab (cf. v.29), perhaps this time including Abishai.

3. The murder of Ish-Bosheth (4:1–12)

The only viable threat left to the throne is Saul’s son Ish-Bosheth and Jonathan’s son Mephibosheth. Chapter 4 removes them from the scene, one explicitly and the other implicitly.

1–3 When Ish-Bosheth heard that Abner had died, “he lost courage”—a typical and expected reaction. Abner’s death left a power vacuum in the north, and it is therefore not surprising that all Israel became “alarmed.”

Among the opportunists eager to take charge are two of Ish-Bosheth’s men, Baanah and Recab, who are “leaders of raiding bands.” Such groups functioned under David’s authorization as well (3:22; 1Ch 12:18) and were not uncommon elsewhere during the early days of Israel’s monarchy (cf. 1Sa 30:1, 8, 15). These two men were members of the tribe of Benjamin and thus loyal to Saul (and Ish-Bosheth).

4 Jonathan’s son Mephibosheth is introduced parenthetically to demonstrate that his youth and physical handicap disqualify him for rule in the north. When the nurse of Jonathan’s son learned that the boy’s father had been killed (1Sa 31), she decided to flee with the boy to a safer location. In her headlong flight the boy fell from her grasp and became permanently crippled. Five years old when his father died, Mephibosheth was now twelve (cf. 2:11).

5–7 Baanah and Recab go to where Ish-Bosheth was staying (doubtless in Mahanaim) and arrive there at the time of siesta, knowing full well that Ish-Bosheth would be sleeping. They gain access to his sanctum through subterfuge and stab him “in the stomach”—a technique rapidly becoming the preferred method of killing.

Ish-Bosheth is assassinated while lying on “the bed in his bedroom,” luxuries available only to the wealthy or to royalty in those days (Ex 8:3; 2Ki 6:12; Ecc 10:20). Recab and Baanah “cut off” (GK 6073) Ish-Bosheth’s head and bring it to David as a trophy of their vile deed. To avoid easy detection they travel through the night a distance of almost thirty miles.

8 Presenting the head of Ish-Bosheth to David, Recab and Baanah remind him that Ish-Bosheth’s father, Saul, had been David’s “enemy.” Indeed, Saul had “tried to take” David’s “life” on many occasions. But now, say the assassins, the Lord himself—to whom belongs all vengeance (cf. Heb 10:30)—has “avenged” (GK 5935) David not only against Saul but also against Saul’s “offspring.”

9–11 David now takes an oath in the name of the Lord. To the assassins’ reminder that Saul had tried to take David’s “life,” the king responds that the Lord delivers his “life” out of “all trouble” (including the difficulties he had faced when he was a fugitive from Saul’s wrath). Like the Amalekite who claimed to have killed Saul (1:10), Recab and Baanah can hardly have expected David’s blistering response to their murder of Saul’s son Ish-Bosheth. The man who had “told” David that Saul was dead was of course the Amalekite (see comment on 1:4). Although he thought he was bringing “good news,” he brought about only his own death at David’s headquarters in Ziklag (cf. 1:1). Expecting a “reward” for his news (cf. 18:22), he received death instead.

If David condemned the Amalekite for delivering the finishing blow to the mortally wounded Saul on the battlefield, then a similar fate is self-evident in this context: (1) Recab and Baanah, “wicked men,” have killed Ish-Bosheth, an “innocent” (lit., “righteous”; GK 7404) man. (2) Although Saul was killed in a context of danger and violence in battle, Ish-Bosheth was murdered in what should have been the secure and peaceful serenity of his own home and bed. David’s outrage (whether real or pretended) over the circumstances of Recab and Baanah’s assassination of Ish-Bosheth causes him to hold them accountable.

12 Death begets death: The Amalekite claimed to have killed Saul, and in retaliation David “put him to death” (v.10); Recab and Baanah have killed Ish-Bosheth (v.11), so David gives the order that they in turn be killed. David’s men mutilate the dead bodies of Recab and Baanah by cutting off their hands and feet. Following the ancient custom to expose to public view the entire corpse of the victim whenever possible (cf. 21:9–10; 1Sa 31:9–10; Dt 21:22–23; Jos 10:26–27), the bodies of Recab and Baanah are “hung” in Hebron. It is ironic indeed that the prolonged struggle between Ish-Bosheth’s men and David’s men begins and ends by the placid waters of a pool (see 2:13).

The contrast between the treatment of the remains of the assassins and of Ish-Bosheth could hardly be more striking. While the dead bodies of Recab and Baanah are impaled in a public setting to disgrace them and deter others, Ish-Bosheth’s head is given an honorable burial in Abner’s tomb at Hebron—the headquarters of David, their political rival.

With the death of Ish-Bosheth, no other viable candidate for king remains for the elders of the northern tribes. Meanwhile David sits in regal isolation, above the fray as always, innocent of the deaths of Saul, Jonathan, Abner, and now Ish-Bosheth. The way is open for his march to the throne of Israel.

4. David anointed king over Israel (5:1–5)

1–3 That the kingdom about to be established under King David is intended as a truly united monarchy is underscored by the use of the word “all” three times (vv.1, 3, 5). The “elders” of Israel, representing the “tribes,” come to David at Hebron with the express purpose of submitting to his rule. Preliminary consultations with them had been initiated by Abner (3:17), but his death had postponed further discussion.

The elders give three reasons for their submission to David. (1) Their reference to themselves as “your own flesh and blood” signifies their sense of kinship with him. David is a “brother Israelite” (Dt 17:15). (2) During Saul’s reign David was Israel’s best army officer. (3) They understand that the Lord has chosen David (cf. 3:18) as Israel’s new king. They sense that the Lord has invested David with the titles of “shepherd” (GK 8286) and “ruler” (GK 5592) as well as “king” (GK 4889). Apart from God himself (Ge 48:15; 49:24), David is the first example of a specific person being called a “shepherd” (cf. Nu 27:17). Moreover, the motif of David as shepherd was prefigured at his earliest anointing (see 1Sa 16:11).

In the ancient Near East, the figure of the shepherd was associated with gentleness, watchfulness, and concern. Since it is the shepherd’s task to lead, feed, and heed his flock, the shepherd metaphor was a happy choice for benevolent rulers and grateful people alike. David thus becomes the paradigm of the shepherd-king (cf. Ps 78:70–72; Eze 34:23; 37:24), and it is not surprising that “great David’s greater son,” Jesus Christ, is introduced frequently as the “good shepherd” (Jn 10:11, 14), the “great Shepherd” (Heb 13:20), and the “Chief Shepherd” (1Pe 5:4).

David is also called a “ruler,” a title that provided a convenient transition between judgeship on the one hand and kingship on the other. David’s sovereignty is underscored by the threefold reference to him as “king” in v.3. He does not go to Israel’s elders in Mahanaim; they come to him in Hebron. Their need for him is greater than his for them—although the stakes are enormous on both sides.

Abner had suggested earlier that Israel “make a compact” with David (3:21). But now that the moment for such an agreement has arrived, the king initiates “the compact” with his (future) subjects. At the same time, however, the covenant should not be understood as bestowing on David the role of all-powerful suzerain and dooming the Israelites to become his craven vassals. The covenant-making formalities take place “before the LORD,” acknowledging that the proceedings are under his guidance and enjoy his blessing (v.12).

As David had earlier been anointed king over Judah (2:4), so now he is anointed king over Israel, “as the LORD had promised through Samuel” (1Ch 11:3). The news of the anointing would soon become well enough known to cause concern in the hearts of the Philistines (v.17).

4–5 David became king in Hebron when he was thirty years old. His overall reign of forty years matches that of Saul (cf. Ac 13:21) as well as that of his son and successor Solomon (1Ki 11:42). His reign consisted of seven and a half years in Hebron over Judah alone (2:11) and thirty-three years in Jerusalem over all Israel and Judah. Although Jerusalem had not been unknown to David before the elders of Israel anointed him (see 1Sa 17:54), he is now determined to make it his capital.

5. David’s conquest of Jerusalem (5:6–12)

6–8 Far and away the most important city in the Bible, Jerusalem is mentioned there more often than any other. Geographically and theologically it is located “in the center of the nations” (Eze 5:5). Known also by its abbreviated name “Salem” (Ps 76:2), it makes only one appearance in the OT before the time of Joshua (Ge 14:18).

Soon after being anointed king over all Israel and Judah (v.5), David deploys his men for a march on Jerusalem “to attack the Jebusites, who lived in the land.” Some of the Jebusites lived outside the fortress at Jerusalem (cf. 24:16), where the temple of Solomon would eventually be built (2Ch 3:1).

The interchange about the “blind” and the “lame” is an example of pre-battle verbal taunting. Thus in v.6 the Jebusites smugly claim that even disabled people can withstand any attack on their fortress, while in v.8 David retaliates in kind by characterizing his enemies as “lame and blind.” The overconfident Jebusites, however, do not count on the skill and determination of David, who captures the fortress of Zion and renames it the “City of David.” For more on the capture of Jerusalem, see 1Ch 11.

Up to this time Jerusalem had been on the border between Judah in the south (Jos 15:1, 5, 8) and Benjamin in the north (Jos 18:11, 16). Tied to no tribe, the City of David could champion its neutrality, central location, and virtual impregnability as qualities that made it and its environs the ideal capital for David’s newly established, united kingdom.

9–10 David thus “took up residence” in Jerusalem where the Jebusites lived (v.6). He then set about to repair the surrounding areas “from the supporting terraces inward.” Joab (David’s commander-in-chief) “restored the rest of the city” (parts of which were doubtless damaged or destroyed as a result of Joab’s attack to capture it; see 1Ch 11:8).

The assertion that David “became more and more powerful” is reminiscent of 3:1. Now as earlier, however, David himself is not the source of his strength; “the LORD God Almighty” (a title for God that is more royal than military), the true King of Israel, grants his power and, as always, is “with him.”

11–12 The events described here occurred a long time after those recorded in vv.6–10. Hiram did not become king of Tyre (a well-fortified island in the Mediterranean Sea) until about 980 B.C., more than twenty years after David was anointed king over Israel and conquered Jerusalem. Hiram continued his friendly relations with Israel’s royal house well into the reign of David’s son Solomon (1Ki 5:1–12; 9:10–14). Hiram traded building materials (which Israel lacked) for agricultural products (which Phoenicia lacked). Thus Hiram sends to David logs of “cedar,” carpenters, and stonemasons. All this activity would eventuate in a “palace for David”—a palace that would fill him with a certain unease (7:1–2).

Witnessing God’s evident blessing on his life, David once again acknowledges the Lord’s role in establishing “him as king over Israel” (v.12). Indeed, David’s throne and dynasty would be established forever (7:11b–16; 22:51; 1Sa 25:28), culminating in the eternal reign of great David’s greater Son (Lk 1:30–33). As Israel’s ideal ruler, David has the privilege of seeing his kingdom “exalted” (GK 5951) by the Lord himself. All this is not for his own sake alone but also, and primarily, for the sake of “his” (i.e., God’s) people.

6. Children born to David in Jerusalem (5:13–16)

13–16 In violation of the divine decree to Israel’s future kings not to “take many wives” (Dt 17:17), David adds “more” concubines and wives to the wives he already has (see 3:5). This is the first time that concubines are mentioned in connection with David.

David fathered many children in Jerusalem. Although vv.14–16 list only sons born to him by his wives, the name of at least one of David’s daughters has survived (Tamar, the sister of Absalom; cf. 13:1; 1Ch 3:9).

The first four names are of sons born to David by Bathsheba (1Ch 3:5), two of whom appear elsewhere in the biblical narratives. The two main claimants to David’s throne in his later years were Absalom (his third-born, 3:3) and Solomon (his tenth-born). Solomon would eventually outlast his rivals for the throne and rule over the united kingdom (cf. 1Ki 1:28–39).

C. David’s Powerful Reign (5:17–8:18)

1. The Philistines defeated (5:17–25)

17–21 As soon as the Philistines learn “that David had been anointed,” they become concerned and go to “search” for him, an unnecessary task if David had already occupied the formidable fortress of Zion. So apparently this incident occurred after David’s anointing and before the conquest of Jerusalem. The “stronghold” to which David retreats is therefore not the fortress of Zion. Also, David “went down” to the stronghold (a person went up to Jerusalem). Possibly the cave of Adullam is the place intended.

The locale of the two battles of vv.20–25 is the “Valley of Rephaim,” on the border between Judah and Benjamin. A relatively flat area, its fertile land produced grain that not only provided food for Jerusalem but also attracted raiding parties.

To meet the Philistine threat David, as always, “inquired of the LORD” by consulting the Urim and Thummim through a priest: Should he attack the Philistines, and would the Lord hand them over to him? The divine answer is emphatically affirmative to both questions. In obedience to God’s command, David goes to engage the Philistines in battle at Baal Perazim, where he defeats them and carries off their idols, which they had probably brought onto the battlefield as protective talismans. The purpose of carrying the Philistine idols away from the battlefield was so that, at David’s command and in accordance with Mosaic prescription (Dt 7:5, 25), they could be burned up (1Ch 14:12).

22–25 On a subsequent occasion, the Philistines again came to attack David, again in the Valley of Rephaim. As before (v.19), David inquires of the Lord. Unlike earlier, however, this time David is told not to go straight up. Apparently the first confrontation was with a smaller contingent of Philistines, whereas now a flanking movement is strategically preferable. The Lord instructs David to “move quickly” as soon as he hears the sound of “marching” in the treetops, promising to go out in front of them. David, acting at God’s command, defeats the Philistines and pursues them “all the way from” Gibeon to Gezer.

2. The ark brought to Jerusalem (6:1–23)

Apart from brief mention in 1Sa 14:18, the ark of the covenant has not been mentioned since 1Sa 7:2. David now adds to political centralization in Jerusalem a distinctly religious focus by bringing to the city the most venerated object of his people’s past: the Lord’s ark—repository of the covenant, locus of atonement, throne of Israel’s invisible Lord.

1–5 For the third time (cf. 5:17–21, 22–25) David assembles his troops, here to serve as a military escort for the ark of the covenant. David’s “chosen men” are reminiscent of Saul’s elite corps of soldiers (see 1Sa 24:2). For at least half a century the ark of the covenant had been sequestered in Kiriath Jearim, in the house of Abinadab—either inaccessible to the Israelites because of Philistine control of the region, or languishing in neglect (perhaps partially because King Saul had shown no interest in it; cf. 1Ch 13:3).

The solemnity of the scene that unfolds is enhanced by the grandiose description of the ark and the repeated references to it. It is depicted as the seat of authority of “the LORD Almighty, who is enthroned between the cherubim” (see 1Sa 4:4). It is also referred to as the “ark of God” and the “ark of the LORD.” The ark “is called by the name/Name,” an idiom denoting ownership and thus here emphasizing that the ark is the Lord’s property. The term “Name” (GK 9005) not only refers to the Lord’s name but also stands for his presence.

David’s intention to “bring up” the ark to the City of David is of course not only commendable but also entirely appropriate. At the same time, however, his first attempt to do so follows Philistine rather than Levitical procedure. David and his men transport it on a “new cart” (see 1Sa 6:7–8). Abinadab’s sons (or perhaps grandsons), Uzzah and Ahio, were given the task of guiding the cart, Ahio walking in front and Uzzah presumably bringing up the rear.

With David taking the lead, the Israelites begin “celebrating.” In this context “before the LORD” means “before the ark.” “Songs” and “harps, lyres, tambourines, sistrums and cymbals” were staple elements on such joyful occasions.

6–11 At the threshing floor of Nacon (possibly a place of sanctity), Uzzah (whose name, ironically, means “Strength”) sensed that the oxen pulling the cart were stumbling and that the ark might fall to the ground. Thus he “reached out” to steady the ark and “took hold of” it. Despite whatever good intentions he may have had, his doom was sealed.

The wrath of divine judgment fell on Uzzah for several reasons. (1) Most obvious was “his irreverent act” of putting his hand on the ark (cf. 1Ch 13:10). (2) Uzzah was transporting the ark in a cart rather than carrying it on his shoulders as prescribed in the law. (3) There is no evidence that he was a Kohathite Levite (cf. Nu 4:15). Just as God had “struck down” (GK 5782) and put to death some of the men of Beth Shemesh for looking into the ark (1Sa 6:19; cf. Nu 4:20), so also God “struck [Uzzah] down” for touching the ark. Ironically, he died “beside” the ark, which he had been attempting to rescue from real or imagined harm.

The Lord’s anger causes David to react first with anger of his own and then with fear. He is understandably indignant that the divine “wrath” (GK 7288) has broken out against Uzzah and resulted in his death, a seemingly harsh penalty for so small an infraction. It is not surprising that David’s anger against God should be mingled with fear of him; he questions whether the ark can “ever” come to him.

David decides that a cooling-off period is in order before he is willing to give further consideration to taking the ark to be “with him” in the “City of David.” Instead, he gives the ark a temporary home in the house of Obed-Edom, a Levite (1Ch 15:17–18, 21, 24–25; 16:4–5, 38)—possibly a Kohathite Levite (cf. Jos 21:20, 24–26; 1Ch 6:66, 69). There the ark remained for three months, during which time the Lord blessed the house of Obed-Edom with numerous descendants (cf. 1Ch 26:8). This fact led to the confidence of David that the Lord would bless the house of David forever (7:29).

12–19 When David is told of the Lord’s blessing on the house of Obed-Edom “because of the ark,” he proceeds to bring the ark up to the fortress, accompanied by “the elders of Israel and the commanders of units of a thousand” (1Ch 15:25). If in the case of the first attempt there was celebration and singing (v.5), now there is “rejoicing.”

“Those who were carrying the ark” were, of course, (Kohathite) Levites (1Ch 15:26). It seems likely that every six steps a bull and a fattened calf were sacrificed, after which the procession continued. Given the proximity of the house of Obed-Edom to the City of David, such a procedure would not have been needlessly cumbersome or time-consuming.

Prefiguring the priestly functions of King David, the prophet Samuel had earlier worn a “linen ephod” (see 1Sa 2:18) and most likely the linen robe normally worn under the ephod (cf. 1Ch 15:27; also Ex 28:31). During the time of the Israelite monarchy, kings occasionally officiated as priests (cf. 24:25; 1Ki 8:64; 9:25).

“With all his might” David “danced before the LORD”—i.e., before the ark, the symbol of the Divine Presence. He and the entire nation now “brought up” the ark from the house of Obed-Edom to Jerusalem. The scene is punctuated with shouts of excitement and triumph and with the sound of ram’s-horn trumpets.

“Michal daughter of Saul” (so described because she is depicted here as being critical of David and is therefore acting like a true daughter of Saul) watched the proceedings from a window. Perhaps still smarting from her separation from her former husband Paltiel (cf. 3:13–16), Michal looks at David leaping and dancing with something less than the love she at one time had for him (see 1Sa 18:20), and she reacts with disgust. Once she had helped David escape through a window (1Sa 19:12); now, peering at him through a window, she despises him “in her heart.”

The ark is brought in and set in its predetermined place “inside the tent David had pitched for it.” Apparently at a somewhat later date, another tabernacle was constructed and installed at the high place in Gibeon (1Ki 3:4; 1Ch 16:39; 21:29; 2Ch 1:3, 5, 13), about six miles northwest of Jerusalem. Thus there were in effect two tabernacles: The one in Jerusalem served as the repository for the ark (1Ch 16:37), while the one in Gibeon housed the other tabernacle furnishings (1Ch 16:39–40).

During the time that the Mosaic tabernacle was not in use (for whatever reason), various offerings continued to be sacrificed without necessary benefit of the bronze altar of burnt offering. Now David sacrifices “burnt offerings and fellowship offerings” as an act of gratitude and consecration “before the LORD” (i.e., honoring the Divine Presence symbolized by the ark). In particular, the fellowship offering signified the desire of the worshipers to rededicate themselves to God in covenant allegiance and to reaffirm their king as God’s covenanted temporal ruler.

After bringing an unspecified number of offerings, David blesses the people “in the name of the LORD Almighty,” once again performing the role of a priest. David adds to his blessing the distribution of food.

20–23 Having blessed the Israelites who witnessed the procession of the ark (v.18), David returns home to “bless” (GK 1385) his own household. When a warrior returned victorious from battle, the women of his hometown would come out to meet him and would celebrate with music and dancing. David might have expected his wife Michal to celebrate his similar triumph in much the same way. If so, he is quickly disappointed.

Michal’s words drip with the “How” of sarcasm: David, the “king of Israel” (an office once occupied by her father Saul), has “distinguished himself.” To what extent David’s state of undress was scandalous is impossible to say (see comment on v.14). Far from the kind of “vulgar fellow” who would be an exhibitionist, David makes it clear that he is most concerned about how the Lord evaluates his actions, insisting that he is celebrating “before the LORD,” not before the “slave girls.” In his rebuke of Michal, he clearly dissociates himself from Saul (“your father”) and the Saulides by asserting that God had chosen him rather than them.

The chapter ends on a somber note: “Michal daughter of Saul” remains childless to her dying day. In ancient times childlessness, whether natural or enforced, was the ultimate tragedy for a woman.

3. The Lord’s covenant with David (7:1–17)

1–3 Settled in his royal house and victor over his enemies, David’s regal status is now beyond question. He can thus now be referred to as “the king.”

David decides that the time has finally come for him to do what any self-respecting king worthy of the name should do: build a house for his God. The contrast between his own house and that of the Lord is stark: The human king is “living” in a sumptuous “palace” while the “ark of God remains” in a mere “tent.” Constructed of the finest materials and with the best available workmanship (see 5:11), David’s palace overwhelms in size and splendor the relatively simple tent. To David’s credit he recognizes that the imbalance needs to be rectified.

Safe within his well-fortified palace and behind secure frontiers, the king doubtless had plenty of time for a major construction project. The Lord has “given him rest from all his enemies around him,” fulfilling during David’s reign a promise he had made to Israel centuries earlier (cf. Dt 3:20; 12:10; 25:19; Jos 1:13, 15) and had already fulfilled during the lifetime of Joshua (Jos 21:44; 22:4; 23:1).

Just as Saul had been advised by Samuel the prophet (1Sa 3:20), so also David would be counseled by various prophets, the most important being Nathan. Agreeing that the king should fulfill his desire to build a house for God, Nathan understands that David will ultimately follow the path of obedient servanthood because “the LORD is with” him.

4–7 The messenger formula (“This is what the LORD says”) pinpoints Nathan as the mediator of the divine oracle. David is now referred to by the Lord as “my servant David,” a description that he willingly and humbly accepts (v.26).

The Lord’s first question in v.5 expects a negative answer (cf. 1Ch 17:4). In the broader context, at least two reasons are given why David himself did not build the temple: (1) He was too busy waging war with his enemies (1Ki 5:3); (2) he was a warrior who had shed much blood (1Ch 22:8; 28:3). Neither reason dims David’s vision, however, and before his death he makes extensive preparations for the temple (cf. 1Ch 22:2–5; 28:2).

The tabernacle will still suffice as the Lord’s dwelling. He reminds Nathan that he has never “dwelt” in a permanent house, not from the day of the Exodus. He has been content with “moving from place to place,” demonstrating his continuing desire to walk among his people. The irony in v.6 must not be missed: Although God condescends to accompany his people on their journey with a tent as his dwelling, a tent carried by them, all along they have in fact been carried by him.

The second question (v.7) also expects a negative answer. It implies that the Lord never required the Israelites nor any of their rulers to build him a “house of cedar.” The word “people” (GK 6639) used with reference to Israel is an important theme in the chapter, employed four times in each half. “I will be your God, and you will be my people” or the equivalent is doubtless the most characteristic covenant expression in the entire OT (cf. v.24; Ex 6:7; Lev 26:12; Dt 26:17–18; et al.).

8–1 la The repetition of the messenger formula (cf. v.4) marks the start of a new section of Nathan’s oracle. Here, however, the word “LORD” has been augmented by “Almighty” (GK 7372), a regal title that stresses the Lord’s function as covenant Suzerain of David, his “servant” vassal.

The divine grant to David is divided into two parts: promises he will realize (vv.8–11a) and those to be fulfilled after his death (vv.11b–16). In vv.7b–8a the Lord reviews his earlier blessings on his servant David. He begins by reminding David of where he found him. Once a mere shepherd boy, David has been given a much weightier responsibility: to be “ruler” (GK 5592) over the Lord’s people Israel.

As the Lord had been “moving from place to place” (v.6) with his people, so he has been with David wherever he has gone. He had promised to “cut off” (GK 4162) David’s enemies from before him. Now the Lord promises three things.

(1) He will make David’s “name great,” a promise that is a clear echo of the Abrahamic covenant (cf. Ge 12:2). It is fulfilled in 8:13.

(2) The Lord will “provide a place” for Israel. This had been predicted long ago (Dt 11:24; cf. Jos 1:3–4). And far from being temporary, the “place” that God would provide would be the land where he would “plant” (GK 5749) them (cf. Ex 15:17; Pss 44:2; 80:8). Having a home of their own, David and his countrymen will be free from “wicked people” and their oppression. Although oppression had been virtually endemic in Israel during the entire period of the judges, such would no longer be the case.

(3) The Lord will give David “rest” (GK 5663) from all his enemies. The method he will use will be to “subdue” them (1Ch 17:10). As always, the ultimate Giver of the rest is God himself.

11b–16 “The LORD declares to you” introduces God’s promises to David’s descendants: a “house” (GK 1074; i.e., a dynasty); a throne and kingdom that will last forever; a “house” (GK 1074; i.e., a temple); and a Father-son relationship, including covenant love that will never be taken away. “House” is obviously used with two different meanings in these verses. All the promises will be fulfilled after David’s death (i.e., his being laid to “rest” with his “fathers”; see comment on 2:30–32).

It is David’s “offspring” who will build the Lord’s temple. The emphasis that his offspring will “come from your own body” forges yet another striking link to the Abrahamic covenant (cf. Ge 15:4). The possibility of understanding “offspring” (lit., “seed”; GK 2446) as either singular or plural is exploited by Paul in Gal 3:16 (see comments on that verse). The Lord goes on to promise that he will “establish” (GK 3922) the “kingdom” and “throne” of Solomon.

In v.13a, “house” means temple. David’s offspring has been designated to build a temple for the Lord’s “Name.” As for v.13b, the Lord promises that the Davidic dynasty, throne, and kingdom will endure “forever” (a fact mentioned seven times in ch. 7).

The Lord’s words in v.14a are doubtless the best known as well as the most solemn in the entire chapter: “I [emphatic] will be his father, and he [emphatic] will be my son.” In its original setting the son is Solomon. The statement is therefore a formula of adoption. Because of its typological use in 2Co 6:18 and Heb 1:5, v.14a has long been considered messianic in a Christological sense.

A further aspect of the father-son metaphor is its covenant setting. The use of “father” for God and “son” for Solomon is thus entirely appropriate in what has justifiably come to be known as the Davidic covenant. Although the Davidic king was to enjoy the unique relationship of being the Lord’s “son,” the Lord would use “men” as agents of divine judgment on Solomon (and his dynastic successors) “when he does wrong.” It is not an idle promise: “The rod” of divine wrath fell on Jerusalem and her citizens because of the sins of David’s descendants (cf. La 3:1).

Finally, the Lord promises that although he “took away” (GK 6073) his love from Saul, the divine “love” (GK 2876) will never “be taken away” (GK 6073) from David’s son Solomon and his descendants, through whom David’s throne “will be established.” That David’s “house” will “endure” echoes Abigail’s insight in 1Sa 25:28. That the throne of David will remain “forever” refers ultimately to Christ, because David’s kingdom came to an end.

Taken together, vv.14b–15 have often been understood to mean that the Davidic covenant is unconditional: No matter what David’s descendants do, the Lord’s love will “never be taken away” from them. But that the Lord will punish the king for disobeying the law at least qualifies the promise if not making it conditional. Kings are not to use the Davidic promise as a justification for wicked behavior.

17 It was incumbent on a prophet to report “all the words" that the Lord commissioned him to proclaim, and Nathan keeps nothing back.

4. David’s prayer to the Lord (7:18–29)

18–21 In response to the Lord’s promises as mediated through Nathan, David “went in” (probably into the tent he had pitched for the ark) and sat “before the LORD.” Beginning his prayer with appropriate humility and deference, David addresses God with a title found in the books of Samuel only here—“Sovereign LORD”—which he employs seven times in vv.18–29. And if God is sovereign to David, he recognizes his own status as vassal by referring to himself ten times as the Lord’s “servant” in vv.19–29.

The central theme of the prayer is David’s “house/dynasty,” a word that occurs seven times (vv.18 ["family”], 19, 25, 26, 27, 29 [twice]). Though his household is insignificant at present, David is confident that it will become great in the future because of the proven reliability of God and his promises. That the Lord has brought him to this point in his experience would be sufficient for David, but he gratefully recognizes that in God’s eyes it is “not enough.” The Lord has even better things in store for him in the future.

The Lord has honored his servant beyond measure, and David asserts that there is scarcely anything more that he can say. He affirms that the Lord “know[s]” (GK 3359) his servant, which perhaps includes the fact that he has “chosen” him (cf. Ge 18:19; 2Sa 6:21).

If David earlier knew that the Lord had blessed him “for the sake of” his people Israel (5:12), he now confesses that the Lord has done a “great thing” (GK 1525) simply for the sake of his “word” (GK 1821) and according to his “will” (GK 4213). The greatness of God overwhelms David, for the Sovereign Lord is “great” (GK 1540), he has done “great” (GK 1525) wonders (v.23), and his name is “great” (GK 1540; v.26).

22–24 Verse 22 is only one among many OT texts describing God as unique. That there is “no one like” the Lord is a major theme in the Song of Hannah (1Sa 2:2; see also 10:24). Three times in v.23 Israel is referred to as God’s “people,” the one elect “nation” (GK 1580) out of all the “nations.” Israel’s powerful “God” is contrasted with the nations’ impotent and ineffective “gods.”

Israel’s matchless Lord has gone out to do three things for his grateful people: “redeem” GK 7009) them, “make a name” for himself, and “perform great and awesome wonders” by driving out the enemy. The ancient establishment of Israel as God’s own people “forever” is now to be channeled through David and his dynasty, which will continue “forever” (vv.25, 29). The OT manifestation of the kingdom of God is now to be mediated through the Davidic monarchy.

25–29 David is much concerned about the permanence of the promise the Lord has made concerning the Davidic dynasty. The covenanted establishment of David’s house would be a visible sign of the greatness of God’s name. Indeed, “LORD Almighty” would become widely known as the appropriate royal title of the Great King, the God of Israel.

David is grateful that God has “revealed” to him his plans and purposes: “I will build a house for you.” He acknowledges that the Sovereign Lord alone is God and that his words are “trustworthy” (GK 622). Although 2Sa 7 never uses the term “covenant” (GK 1382) of God’s promises to David, “good things” (GK 3208) is a technical term synonymous with “covenant” in contexts like this (cf. 2Ch 21:7; Ps 89:3; Isa 55:3).

David concludes his prayer with a request to the Lord to “be pleased” to bless the Davidic dynasty. Since it is the Sovereign Lord himself who has promised, David speaks with the calm assurance of a man who knows that his house will continue forever “in your sight.” The prayer of David thus ends on a note of confident contentment.

5. David’s enemies defeated (8:1–14)

1 It is impossible to know for certain whether the divine promises of ch. 7 preceded or followed the divine victories of ch. 8. In any event, the account of the Philistine defeat resumes the story told in 5:17–25. Exactly what David “took” from the Philistines cannot be determined with certainty. The importance of the conquest of Philistia by David can scarcely be overestimated.

2 As David defeated the Philistines, so also he defeated the Moabites. Why he fought against Moab is unknown, especially since the Moabitess Ruth was his ancestress (cf. Ru 4:10, 13, 16–17) and Moab had at one time sheltered his parents (see 1Sa 22:3–4). His method of executing a specified number of prisoners of war is not attested elsewhere. Only a third of its inhabitants are “allowed to live” (cf. 1Sa 27:9, 11).

The Moabites “became subject to” David, which included bringing “tribute” (GK 4966). This word often means “gift(s)/offering(s)” presented as sacrifices, which are thus understood as tribute brought into the throne room of the Great King. After David’s death, nations conquered by him would continue to bring tribute to his son Solomon (1Ki 4:21) and his successors.

3–12 Despite the limited information available about Aram during David’s reign, the space given to its conquest in this chapter testifies to its overall significance in the scheme of things. David “fought” and “defeated” the Arameans. His main adversary is “Hadadezer son of Rehob.” Hadadezer (“[The God] Hadad is [my] help”) is the Hebrew form of an Aramean dynastic royal title.

The pronoun “he” (v.3) most likely refers to Hadadezer, for David could not have extended his power to the Euphrates before the defeat of Hadadezer. Marking the eastern reaches of David’s realm, the Euphrates was one of the fixed boundaries of the land promised to Abraham (Ge 15:18).

In driving back the forces of Hadadezer to the Euphrates, David obtained substantial numbers of chariots, charioteers, and foot soldiers. Most of the horses that pulled the chariots he “hamstrung” (i.e., severed the large tendon above and behind their hocks to disable them). Reinforcements from Damascus came to “help” Hadadezer, but David defeated them, and the Arameans became tributary to him.

Part of the tribute that David took from Hadadezer was his officers’ “gold shields,” ceremonial or decorative shields not used in battle (cf. SS 4:4; Eze 27:11). They were brought to Jerusalem and eventually placed in Solomon’s temple, where they remained for well over a century (see 2Ki 11:10). Three towns that belonged to Hadadezer yielded a “great quantity of bronze” to King David. Solomon used the bronze in his construction of the articles of the temple (1Ch 18:8).

The news of David’s defeat of the entire army of Hadadezer eventually reaches the ears of Tou king of Hamath, who had been at war with Aram. Tou wants to make peace with David, so he sends his son Joram to “congratulate” him on his victory over Hadadezer and to bring a voluntary gift of “articles of silver and gold and bronze” in order to gain David’s goodwill.

In grateful acknowledgment of divine blessing, David dedicates all the articles—whether received as gifts, as tribute, or as plunder—to the Lord. After recording the defeat of Aram in the north, the narrator includes a summary of David’s conquest of neighboring nations in every direction: south (Edom), east (Moab and Ammon), west (Philistia), and southwest (Amalek).

13–14 David’s “striking down” the Edomites was accomplished through Abishai son of Zeruiah (see 1Ch 18:12), but David gets the credit because he is the supreme commander. At the same time, Abishai’s brother Joab strikes down 12,000 Edomites (cf. the title of Ps 60). David then “put garrisons throughout Edom.” In all his successes, however, the Lord was the One who “gave victory.”

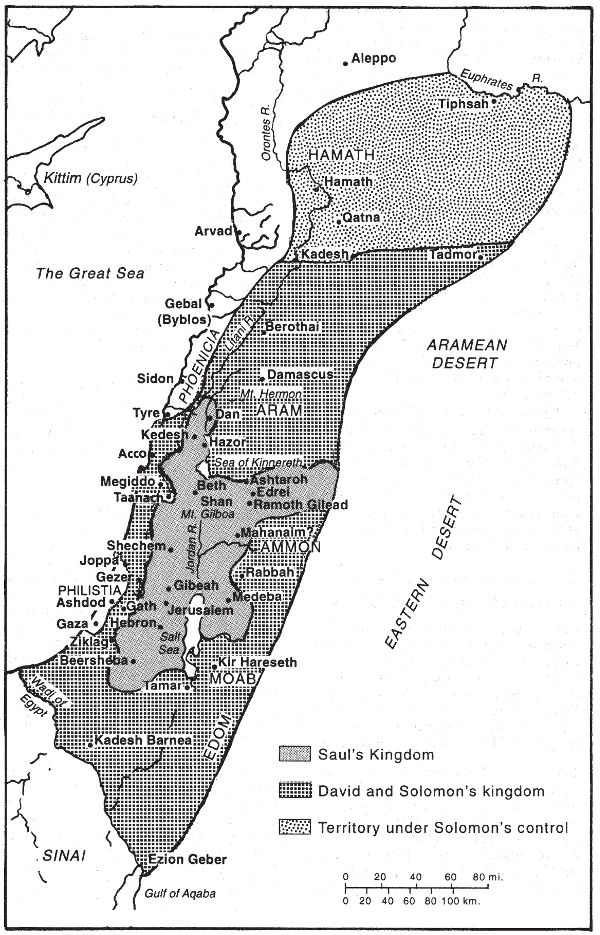

The regions added to David’s realm through the defeat of all the nations more than doubled the territory of Israel, thus initiating the golden age of Israelite history. David’s new boundaries correspond to those outlined in the divine promise to Abraham (Ge 15:18; cf. also Dt 11:24; Jos 1:4).

6. David’s officials (8:15–18)

15 A mighty warrior, King David now reigns over “all” Israel and administers justice and equity to “all” his people. “Doing what was just and right” was the hallmark of a strong king in the ancient Near East and included such reforms as the elimination of oppression and exploitation (cf. esp. Ps 72).

16–18 As expected, the commander of David’s army is Joab son of Zeruiah. Jehoshaphat is recorder and remains so into the reign of Solomon (1Ki 4:3). The function of the recorder was apparently either to have oversight of state records and documents or to serve as a royal herald. Though appearing here by name for the first time, Zadok was probably one of the preliminary fulfillments of the oracle of the man of God in 1Sa 2:35. It is striking, and perhaps intentional, that Jehoshaphat (meaning “The LORD judges”) and Zadok (“Righteous”) are listed in sequence so soon after David is described as doing what is “just and right” (v.15).

© 1986 The Zondervan Corporation

Zadok shared priestly duties with Ahimelech during at least part of the reign of David. Possibly Zadok was appointed to offer sacrifices at the tabernacle in Gibeon (cf. 1Ch 16:39–40) and Ahimelech to minister before the ark of the covenant in Jerusalem.

The function of Seraiah as “secretary” was as much that of secretary of state as it was that of royal scribe. Benaiah was in charge of David’s bodyguard (23:22–23), became a royal executioner (cf. 1Ki 2:25, 34, 46), and eventually rose to the position of commander-in-chief of Israel’s army (1Ki 4:4). The Kerethites and Pelethites constituted a corps of foreign mercenaries employed as David’s bodyguard (for details see ZPEB, 1:787).

The list of David’s officials concludes by reporting that his sons (how many and who they were is not stated) were “royal advisers” (GK 3913), the same word translated “priests” in v.17. Apparently in early Israel there were priests who were (1) connected with the royal house, (2) not of the Levitical order, and (3) serving a function that is still largely unknown to us.

D. David’s Court History (9:1–20:26)

1. Kindness to Mephibosheth (9:1–13)

1 Now that he is the undisputed king, David can afford to be magnanimous. He thus actively seeks out anyone “still left of the house of Saul” so that he might show “kindness” (GK 2876) to him “for Jonathan’s sake.” David’s desire to show kindness derives from his long-standing covenant relationship with the deceased Jonathan (1Sa 18:3; 20:12–15).

2–5 David makes contact with the house(hold) of Saul through Ziba. David asks him whether Saul’s house “still” has a survivor to whom David would be able to show kindness. Ziba responds that there “still” remains one of Jonathan’s sons, a man who is “crippled in both feet.” He tells David where the man is living—in Lo Debar, a town on the other side of the Jordan. David sends for Mephibosheth.

6–8 David meets “Mephibosheth son of Jonathan, the son of Saul” (his ancestry is fundamental to the narrative). Mephibosheth approaches David with “your servant” and bows down to him. Doubtless knowing what had happened to his uncle Ish-Bosheth (cf. 4:5–8), he is understandably apprehensive. To put him at ease David tells him not to be afraid. True to his earlier promise (vv.1, 3), David declares emphatically that he will show Mephibosheth kindness for Jonathan’s sake. David’s specific expressions of covenant loyalty to Saul’s grandson consist of (1) restoring to him all the land that had belonged to Saul (though certainly not his father’s kingdom; cf. 16:3), and (2) welcoming him as a perennial guest at his table. “Eating (food) at the (king’s) table” can be understood as a metaphor referring to house arrest (cf. 2Ki 25:29), though that is not necessarily David’s intention.

Again Mephibosheth “bowed down” and, speaking to the king, referred to himself as “your servant” (cf. v.6). He was grateful that David should “notice” him. Becoming more craven still in his submission to David, Mephibosheth referred to himself as a “dead dog.”

9–11a Ziba is “summoned” into David’s presence, and David announces that he has turned over to Mephibosheth the property belonging to Saul and his “family.” David then gives Ziba (together with his sons) the responsibility to “farm” the land for Mephibosheth, since the latter is a cripple (v.13). Ziba is also to “bring in the crops” so that Saul’s grandson may “be provided for”—a phrase that seems to cast a cloud over David’s generous pledge that Mephibosheth would always “eat [food] at [the king’s] table,” in that it appears that Mephibosheth would be supplying some if not most of his own provisions.

11b–13 David’s intention to show kindness to Saul’s survivors (v.1) is now implemented. Some time has passed since the earlier mention of Mephibosheth in 4:4, when he was no more than twelve years of age. He is now old enough to have a “young son” named Mica. Mephibosheth moves from Lo Debar to Jerusalem.

2. The Ammonites defeated (10:1–19)

1–5 The deceased king of the Ammonites was Nahash (1Sa 11:1–2). When political power is based on dynastic rule, a king about to die can reasonably expect his son to succeed him as king (cf. 2Ki 13:24). Thus Hanun becomes king of Ammon. Assuming that Nahash is the same Ammonite king defeated by Saul (1Sa 11:1–11), the kindness he showed to David may have been expressed during David’s days as a fugitive from the Israelite royal court. David now wants to reciprocate by showing “kindness” (GK 2876) to Nahash’s son, thereby cementing the alliance already existing between the two nations. Just as the events of ch. 9 promoted domestic harmony inside Israel, so this event helped maintain the viability of one of David’s international agreements and strengthen his position outside Israel.

The means chosen by David to show kindness is sending a delegation to “express his sympathy” on the death of Nahash. The Ammonite “nobles,” convinced that David’s delegation are spies, share their suspicions with Hanun. Accepting the assessment of his men, Hanun decides to refuse David’s cordial overtures and to humiliate David’s messengers. He begins shaving off “half of each man’s beard,” no doubt vertically rather than horizontally to make them look as foolish as possible. He then cuts off their garments “in the middle at the buttocks” and sends them on their way. Forced exposure of the buttocks was a shameful practice inflicted on prisoners of war (cf. Isa 20:4).

Hanun’s treatment of David’s men was clearly a violation of the courtesies normally extended to the envoys of other states in ancient times. Indeed, the indignities heaped on them are a grotesque parody of the normal symbolic actions that accompanied mourning. When David was told about their humiliation, he sent messengers to tell them to stay at Jericho until their beards had grown back; only then could they return to Jerusalem. The regrowth of the beards of David’s men would portend disaster for the Ammonites.

6–14 The Ammonites’ perception of themselves is accurate: They have become a “stench” in David’s nostrils, affirming that David would almost surely be expected to declare war against Ammon. In anticipation of that likelihood the Ammonites, at enormous cost, hire a large army of Arameans to supplement their own troops.

Upon learning that the Ammonite-Aramean coalition has been formed, David takes no chances. He sends out the entire army, under the leadership of his commander Joab, to engage them. While the Ammonites prepare to defend their city by amassing at its most vulnerable point, the “entrance to their city gate,” the troops from the various Aramean districts are deployed in “the open country.”