INTRODUCTION

1. Background

God used the history of the ancient kingdom of Israel to reveal truths about himself and his relationship to humankind. But while he inspired the OT writers of the books of both Kings and Chronicles to interpret this history, their theological messages are distinct. If 1 and 2 Kings, composed after the final collapse of the kingdom in 586 B.C., concentrates on how sin leads to defeat (2Ki 17:15, 18), then 1 and 2 Chronicles, coming after the two returns from exile in 537 and 458 B.C., recounts, from the same record, how “faith is the victory” (2Ch 20:20, 22). Readers today may therefore find strength from God, knowing that his moral judgments (Kings) are balanced by his providential salvation (revealed in Chronicles).

2. Date and Authorship

While Chronicles contains no direct statement about the circumstances of its own composition, still a fairly clear picture does emerge from the biblical data. The last-recorded event in 2 Chronicles is the decree of Cyrus in 538 B.C., permitting the Jews to return from their exile in Babylon (36:22–23). One genealogy in 1 Chronicles (3:17–21) includes King Jehoiachin’s grandson Zerubbabel, who led this return in the following year, and it goes on to name two of Zerubbabel’s grandsons—Pelatiah and Jeshaiah—thus extending the time to about 500 B.C. The sons of four other men are then mentioned, but without indication of their place in the genealogy. The last of these is Shecaniah, whose line reaches down to seven great-great-grandchildren (3:24). So if Shecaniah belongs to the same general period as King Jehoiachin (born 616), these four additional generations would again suggest a time around 500 B.C. as the earliest possible date for Chronicles.

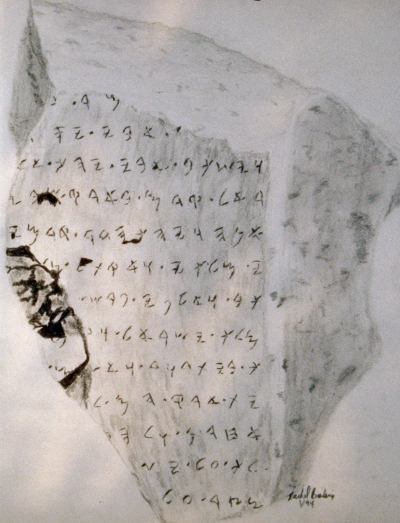

Recent discoveries have produced external evidence by which the latest possible date for the books may now be set. The discovery of fragments of an actual manuscript of Chronicles among the Dead Sea Scrolls makes a third-century date difficult to maintain; thus it is imperative to place the Chronicler’s activity in the Persian period (c. 538–333 B.C.). More specifically, if we accept the tradition that the OT canon was finalized during the general period of the Persian monarch Artaxerxes I, who died 424 B.C. (cf. Ne 12:22, where the reference to Darius II—who was crowned in 423—is the last historical allusion to appear in the OT), then Chronicles would have to have been written before 420. If its composition, moreover, is associated with the work of Ezra, the Aramaic language found in the book that bears Ezra’s name matches that of the Elephantine papyri, which likewise belongs to the fifth century B.C.

Relationships between the books of Chronicles and Ezra provide the most important single clue for fixing the date and also the authorship of the former volume. Since Chronicles appears to be the work of an individual writer, who was a Levitical leader, some identification with Ezra the priest and scribe (Ezr 7:1–6) appears possible from the outset. This conclusion is furthered, moreover, by the personal qualities that the writer displays. The literary styles of the books are similar, and their contents have much in common: the frequent lists and genealogies, their focus on ritual, and their joint devotion to the law of Moses. Most significant of all, the closing verses of 2 Chronicles (36:22–23) are repeated as the opening verses of Ezra (1:1–3a). Jewish tradition affirms that Ezra wrote Chronicles, along with the book that bears his name.

For those, therefore, who accept the historicity of the events recorded in Ezra—from the decree of Cyrus in 538 down to Ezra’s reform in 458–457 B.C.—and the validity of Ezra’s autobiographical writing within the next few years, the date of composition for both books as one consecutive history must be about 450 B.C., and the place, Jerusalem.

3. Sources

If Ezra the scribe is the man responsible for the present book of Chronicles, his “scribism” may well account for the careful acknowledgment of historical sources that appears through the volume. These fall into the following categories.

a. Genealogies

For the tribe of Simeon, the author of Chronicles explains, “They kept a genealogical record” (1Ch 4:33); and for Gad he identifies his sources even more closely: “These were entered in the genealogical records during the reigns of Jotham [751–736 B.C.] king of Judah and Jeroboam [II, 793–753] king of Israel” (5:17). He refers to similar official genealogical lists for Benjamin (7:9), Asher (7:40), “all Israel” (9:1), the Levitical gatekeepers (9:22), and the family of Rehoboam (2Ch 12:15); and the very nature of his book suggests numerous others that just did not happen to be so mentioned.

b. Documents

Since the Chronicler not only describes how the Assyrian king Sennacherib “wrote letters” against Judah but then goes on to cite excerpts from them (2Ch 32:17–20), these too seem to represent a literary source (cf. an immediately preceding message that is quoted as deriving from this same monarch, vv.10–15). The book also concludes with a proclamation made by the Persian king Cyrus, which he “put in writing” (36:22–23). Another kind of documentary source underlies the detailed descriptions of the Solomonic temple in Jerusalem, because references are made to the plans “of all that the Spirit had put in his [David’s] mind” for it (1Ch 28:11–12)—and not just in his mind, but “‘All this,’ David said, ‘I have in writing from the hand of the LORD upon me’ ” (v.19).

c. Poems

The author alludes to songs of praise in the words of David and Asaph in 2Ch 29:30 (cf. the titles to Pss 50; 73–83), and in 35:25 to laments for Josiah that were chanted by Jeremiah (not to be identified with his later, canonical Lamentations over Jerusalem). Neither is actually quoted, though the allusions suggest the author’s use of poetic sources (cf. David’s reemployment of Pss 95:1–5; 96; and 106:1, 47–48, which Ezra did quote in 1Ch 16:8–36).

d. Prophecies

Among its sources Chronicles refers to at least eleven different prophetic books: those by the earlier prophets Samuel, Gad (1Ch 29:29), Nathan (1Ch 29:29; 2Ch 9:29), Ahijah (2Ch 9:29), Shemaiah (12:15), and Iddo, including both the “visions of Iddo” (9:29) and his “annotations” (13:22); and those by the later prophets Jehu son of Hanani (20:34), Isaiah, including both his “vision” (the OT book, 32:32) and his last history of Uzziah (26:22), and Hozai (33:19, perhaps meaning simply a book of “the seers”). Second Chronicles alludes (36:22) to the fulfillment of Jer 29:10, and the author seems to quote from Jer 29:13–14 in 2Ch 15:4 (unless both are drawing on Dt 4:29).

e. Other histories

Ezra’s major reference work was “the book of the kings of Israel and Judah” (2Ch 27:7; 35:27; 36:8; et al.). He also refers at one point to the “annals of King David” (1Ch 27:24, which may have been part of the same work) and to the “annotations on the book of the kings” (2Ch 24:27). But though much material from the canonical books of 1 and 2 Kings does reappear in Chronicles, these cannot be the source here cited, since passages such as 1Ch 9:1 and 2Ch 27:7 refer to “the book of the kings” for additional data on genealogies and wars, about which nothing further actually occurs in our canonical books. So while Ezra did use this major reference work directly, it must have been some larger court record—authentic but now lost—from which both Kings and Chronicles drew.

All in all, 57.8 percent of the text of Chronicles exhibits verbal parallels with other portions of the OT. These include especially the Pentateuch and Joshua for the genealogies and other such listings, and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings for the history.

4. Occasion and Purpose

When Ezra returned from Babylon in 458 B.C., his heart was set on enthroning God’s law in the postexile community of Judah (Ezr 7:10). He took immediate steps to restore temple worship (7:19–23, 27; 8:33–34) and to eliminate a number of mixed marriages that had arisen between certain Jews and their pagan neighbors (chs. 9–10). Based on powers granted him by the Persian king (7:18–25), Ezra seems to have been the one who commenced the refortification of Jerusalem (4:16), though subsequently thwarted by bitter Samaritan opposition (vv.17–23; cf. Ne 1:3–4). Not until 444, when Ezra was joined by Nehemiah, were the walls actually finished (Ne 6:15–16) and the law of Moses formally recognized by the community (ch. 8). Yet if Ezra was the Chronicler, then the appearance of his book about 450 becomes explainable as a concrete literary means to aid in the achievement of his purpose of rebuilding the theocracy (i.e., the acknowledgment of God as their king).

5. Theology

Ezra honors the transcendent majesty of God (1Ch 29:11) and quotes statements from past history describing him as above all gods (2Ch 2:5), dwelling in heaven (6:18; 7:14), and ruling all earth (20:6). The Lord’s presence must be mediated, therefore, by his “name” (which carries the force of his person, 12:13), especially in the temple (1Ch 22:7; 29:16), and by his Spirit, especially for communications (1Ch 12:18; 2Ch 15:1; 24:20). Angels occupy a greater place in Chronicles than in the corresponding parts of the other OT histories (1Ch 21:12 or 21:18, 20, 27), as does also the Lord’s mediation through Satan (21:1).

Yet God can be immanent as well, intervening into history (1Ch 12:18; cf. 2Ch 20:13) in answer to human prayers and songs (2Ch 14:11; 18:31; 20:9–12). The continuity of his concern is emphasized by the phrase “God of [the] fathers,” used in quotations (1Ch 29:20; 2Ch 20:6) and by the Chronicler himself (2Ch 13:18; 15:12); and his covenant love for Israel (6:14) is recognized even by foreigners (2:11; 9:8). The Lord is the God of revelation, who fulfills his predictions (10:15; 36:21) and keeps his promises (1Ch 17:26: 2Ch 1:9; 6:15). Prophets of God who appear in Chronicles (but not in Kings) include Iddo (2Ch 13:22), Azariah son of Oded (15:1, 8), Eliezer (20:37), and Jeremiah (35:25; 36:12, 21–22). Corresponding attention is given to the written Mosaic Law, which must be taught (17:9) and honored (31:4, 21).

6. Theological Themes and Interests

A careful reading of Chronicles shows that the author has certain recurring theological interests that he promotes throughout his work.

a. Promise of God

The Lord takes center stage and leaves no doubt as to who is in charge. Thus, rather than giving political, sociological, military, or economic explanations—or stating immediate causes for events—the author presents God as the Lord of history and the cause of its events.

The prominence of God may be seen in several incidents. God put Saul to death and gave the kingdom to David (1Ch 10:14); God routed the armies of Jeroboam when he attacked Abijah (2Ch 13:13–16); God destroyed the mighty army of Zerah when it battled Asa and his smaller forces (2Ch 14:12–13); the Lord established the kingdom of Jehoshaphat (2Ch 17:5) and defeated a military alliance of Moab, Ammon, and Mount Seir even before the Hebrew army began to fight (2Ch 20:22–23).

Perhaps the finest example of God’s direct, divine intervention in history may be seen in the way he utterly destroyed the mighty army of Sennacherib when that proud Assyrian ruler dared to challenge the power of the Almighty and to compare him to the gods of the other nations (2Ch 32:16–22).

b. Retribution

The idea of sowing and reaping is hardly new to Chronicles, but it is modified in at least two ways. (1) The burden of obedience lies primarily on the shoulder of the king of the nation. (2) The principle does not work automatically or mechanically. The sovereign ruler is often warned by a prophetic word; hence the ruler can repent and avert a calamity or military defeat (cf. 2Ch 7:14).

c. Vocabulary

The author’s third theological interest is his constant use of standard vocabulary and expressions like “seeking God,” “pure heart,” “faithfulness,” and “forsaking the LORD.” Because seeking God and being faithful to him bring about his blessings, it is not surprising to find many exhortations and injunctions to do so.

d. Things used in worship

A fourth interest is the ark, the temple, and the priesthood. Two chapters cover the transporting of the ark to Jerusalem; eight chapters deal with the preparation for building the temple. Three chapters describe the actual construction of the temple, and three more cover its dedication. Furthermore, three chapters cover Josiah’s reforms, with special emphasis on the restoration of the central sanctuary and its functions.

e. Worship

A fifth interest is closely related to Israel’s worship at the temple. The Chronicler is concerned about the nature of true worship as opposed to correct ceremony. This concern for the right attitude of the heart may be traced in two ways. First, the word “heart” (GK 4222) is used some thirty times in Chronicles. Thus the activity of seeking God should be accompanied with the right inner attitude. A second way of tracing the Chronicler’s concern for true worship may be seen from his treatment of Hezekiah’s reform. Hezekiah is portrayed as one of the godliest Judean kings.

f. Kingdom

A sixth interest is the kingship in Israel. The kingdom of God and the kingdom of Judah are often treated as if they are one and the same entity (cf. 1Ch 28:5; 29:23). The kingdom is important as the guardian of the temple. After the division of Solomon’s kingdom, the Judean kings regularly expressed their commitment to God in terms of religious reforms (cf. reigns of Hezekiah and Josiah). True worship in Israel was not preserved by godly priesthood but by godly kingship.

g. History

A seventh interest is seen from the way the Chronicler records historical events. For example, it is not enough for him to describe the building of the temple; he must go beyond that and point out the striking resemblance of this event to the construction of the tabernacle in the desert.

h. Omissions

A final interest of Chronicles is in the material that he chose to omit from his discussion of Israel’s history. From the reign of David, he deleted three main blocks of material. He left out the events found at 1Sa 15–31. Also deleted is the material found in 2Sa 1–4. The third block of omitted material involves David’s sin with Bathsheba and the problems that followed it (2Sa 11–1Ki 2, with the exception of the census).

Concerning the reign of Solomon, Chronicles omitted the struggle between Solomon and Adonijah for the throne, the steps Solomon took to solidify his position, and the material dealing with Solomon’s many foreign wives, with the resultant spread of idolatry and God’s punishment of the king for this sin (1Ki 11).

After the division of Solomon’s kingdom, the Chronicler did not deal with the northern kingdom on its own terms and for its own intrinsic interest. Instead he dealt with it only as it came into contact with the kingdom of Judah.

The Chronicler recorded a history of Israel in which he chose both to emphasize certain points and to delete some material. This was no plot or attempt to suppress the truth. In developing his theological commentary on the events of the past, he left out certain elements that did not contribute to the point he was emphasizing. Those who want another perspective on history can read the former prophets or recite the facts that were well known to Israel.

EXPOSITION

I. Genealogies (1:1–9:44)

A. Patriarchs (1:1–54)

Chronicles begins with nine chapters of genealogies. Their purpose was to show the place that the 450 B.C. postexilic community of Judah occupied within total history. They serve two practical functions. (1) For the immediate situation, genealogies were important in providing the framework within which true Hebrews could establish their genealogical roots and by which religious purity could be maintained against outside groups and influences.

(2) For the church’s overall perspective, the genealogies reflect the providential design that marks the sweep of history from Eden onward. Particular names serve as reminders of God’s dealings in the past; and the genealogies’ focus on David and his dynasty embodies the OT hope for the future Messiah, with the meaningfulness that this provided for Ezra’s generation.

1–4 Ezra’s survey commences with Adam, not just Abraham, the father of the Hebrews. This points to the unity of the race (Ac 17:26) and to the universality of God’s redemptive program within history (Ge 3:15). Verses 1–4 are compiled from Ge 5. Seth’s brothers, Abel and Cain, with the latter’s line (Ge 4:17–25), are omitted as irrelevant.

5–7 Verses 5–23 are drawn from the “table of nations” in Ge 10:2–29. The seven sons of Japheth founded the people of Europe and northern Asia (e.g., from Javan comes Greek Ionia; from Gomer, the ancient Cimmerians of the Russian plains; and from Madai, the Medes and Persians of Iran. Tubal and Meshech were ancestors of the eighth-century Tabali and Mushki, who inhabited the Turkish plateau, according to contemporary Assyrian inscriptions). Areas proposed for the first two Greek subgroups in v.7 include Elishah (in south Greece) and Sardinia; the latter two—“Kittim and Rodanim”—denote the islands of Cyprus and Rhodes.

8 The four sons of Ham founded ethnic groups in Africa and southwestern Asia (e.g., Put in Libya on the Mediterranean coast of Africa west of Egypt; and Cush, or “Ethiopia”).

9–11 Yet the five listed sons of Cush founded tribes that extended eastward from the coast of the Red Sea, across southern Arabia, to the Kassites in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. The second river of Eden can thus be said to border Cush (Ge 2:13), and Babylon and Assyria pertain to the Cushite leader Nimrod (10:8–11).

12–16 The Hamitic Philistines were “sea peoples” before settling in Palestine, coming from the Casluhim, who were of Egyptian origin but are related to the Minoan culture of Caphtor (Crete) and the southern coast of Asia Minor (Am 9:7).

17 The five sons of Shem produced the peoples who remained closest to humankind’s original home in west-central Asia. Yet they ranged from Elam, north of the Persian Gulf, to Aram in Syria and Lud (Lydia) in central Turkey.

18 The name Eber forms the root of “Hebrew”; but this patriarch was ancestor not only of Abraham (v.27), but also of a number of other unsettled people, known in ancient history as Habiru or Apiru.

19–23 The only “dividing up” of the earth to which Genesis makes reference in its post-diluvian context is that which occurred at the confusion of languages at Babel (Ge 11:1–9). The name Peleg seems to have been derived from this event (see NIV note).

24–27 The list of names from Shem to Abram sums up the table of Ge 11:10–26. Both men constitute significant reminders of God’s special relations with his people: the first, as the initial example of the Lord’s association with a particular part of humanity, i.e., the Semites (Ge 9:26), and Abraham as a climactic witness to divine election (12:2; 17:7). The latter’s change of name is explained in Ge 17:5.

28–34 The information on the families of Abraham and Isaac is identical with that found in Ge 25:1–4, 9, 13–16. Abraham’s nomadic Arabian descendants through his two subordinate wives, Hagar and Keturah, are given first, before the biblical record focuses on Sarah’s son, Isaac, who was the child of promise. Arabs became increasingly influential in Judah (cf. Ne 4:7–6:l) after occupying Ezion Geber at the northeast end of the Red Sea in 500 B.C.

35 The remainder of ch. 1 summarizes the “table of Edom” in Ge 36:4–5, 11–13, 20–28, 31–43—with few scribal corruptions in spelling. The subject of the rest of 1 and 2 Chronicles is Jacob (Israel) and the Twelve Tribes that descended from him; but before the record focuses on this younger of Isaac’s twin sons, it lists the elder brother, Esau, and the Edomite tribes that he founded. They were Israel’s closest “brothers” (Ob 10, 12) and near neighbors, after Arab pressure forced them into southern Judah fifty years prior to Ezra.

36–37 Timna, a daughter of Seir (v.39), became a subordinate wife of Esau’s son Eliphaz (Ge 36:12) and was later honored by having her name bestowed on an Edomite chieftain and his district (36:40; cf. 1Ch 1:51).

38–41 Seir belonged to a group called “Homes” (Ge 36:20), the ancient Hurrians, a major people of Mesopotamia. Some had settled in Edom (= Seir) before the coming of Esau (Dt 2:12, 22).

42 Uz was the name of the home of the patriarch Job (Job 1:1), who may thus have been an early Edomite descendant of Esau (cf. La 4:21). Similarly, Esau’s son Eliphaz, the father of Teman (v.36), seems to have been in the ancestry of Job’s friend Eliphaz the Temanite (Job 2:11).

43–54 The death of King Hadad (v.51) is not mentioned in Ezra’s biblical source (Ge 36:39), perhaps because Hadad II was still living when Moses wrote this part of the Pentateuch, a thousand years before the writing of Chronicles.

B. Judah (2:1–4:23)

1. The clan of Hezron (2:1–55)

Chapter 2 resumes the specific development of the nation of Israel. It continues from 1:34, where the two sons of Isaac had been introduced. Since the line of the elder, Esau, was summarized in 1:35–54, Ezra can now concentrate on the younger of the twins, Israel. But while our Chronicler lists all twelve of the sons of Israel-Jacob, his attention quickly focuses on Judah (v.3), the description of whose tribe occupies the next two and one-half chapters. Indeed, after a supplement on those portions of the tribe of Simeon that remained as neighbors to southern Judah (4:24–43), the genealogies of Chronicles devote themselves principally to Benjamin (chs. 8–9) and the priestly tribe of Levi (ch. 6). Only chs. 5 and 7 are left, for outlines, respectively, on the tribes of Transjordan and north Israel. The land that was occupied by the Jews who returned from the Babylonian exile consisted primarily of the tribal territories of Judah and Benjamin. Also, the people who made up Ezra’s community were largely from these same two tribes (Ezr 1:5; 10:9), which had composed the former southern kingdom. In his effort to maintain national purity, it was therefore natural that the Chronicler should concentrate on these particular genealogies. Judah was especially prominent (Ezr 4:4, 6): from it the very name “Jew” is derived.

Among the ten-listed grandsons of Judah (1Ch 2:5–6; 4:21–22), the primary interest of this chapter (from 2:9 onward) rests on Hezron, the elder son of Perez, from whom were descended some of the leading elements of Judah’s later population. Hezron’s third son, Caleb, in his turn received major attention in two sections (vv.18–20 and 42–55; cf. 4:1–4), though Hezron’s second son, Ram, is presented first, because he embodies the messianic hope of Israel: from him comes the family of David (2:10–17).

1 Verses 1–2 are drawn from Ge 35:22–26 and Ex 1:1–5. All the passages list in first place Jacob’s six sons by his wife Leah (from Reuben through Zebulun), in the order of their birth; and the Pentateuchal sources place the four sons of the handmaids (Dan through Asher, in their order of birth) after Jacob’s younger son by his wife Rachel, namely, Benjamin.

2 Chronicles, however, follows Genesis in placing Joseph before Benjamin; and before them both it puts Dan, following Zebulun, perhaps because these last two receive no further treatment in Chronicles.

3–4 These verses reflect the sordid dealings that Judah, his sons, and his Canaanite daughter-in-law Tamar had with each other (Ge 38; esp. vv.2–7, 29–30; cf. 46:12). Yet God in his grace used Tamar to be an ancestor of David and of Jesus Christ (Mt 1:3)!

5 Since Judah’s first two sons died without issue, and since his third son is taken up in ch. 4 (vv.21–23), the present section focuses on the remaining two, as listed in Ge 46:12 and Nu 26:21.

6 Except for Zimri, these Zerahites can be identified from 1Ki 4:31 as later descendants, not immediate “sons,” of Zerah. Ezra singled them out as examples of God-given wisdom (cf. v.20) during the Solomonic period. Heman and Ethan, moreover, became authors of inspired psalmody (Pss 88–89), with which Ezra’s concern for proper worship caused him to be involved. These authors must not, however, be confused with David’s musicians, Heman, Asaph, and Ethan (1Ch 15:19), who were from the tribe of Levi, not Judah (cf. 6:33–44).

7 Carmi is another Zerahite, identifiable from Jos 7:1 as an immediate son of Zimri. While the latter has been equated with Zerah’s son Zimri, he really appears (in Jos 7:17–18) to belong to the time of his direct grandson Achan. The last named is here called Achar (“disaster”) because he was a “bringer of disaster” on Israel. The name reminds us of his sin under Joshua at Jericho and how God’s judgment may bring consequent disaster on his people (Jos 7:25; cf. 6:18 and the naming of the place as Achor in 7:26).

8–10 Verses 9–12 are drawn from Ru 4:19–22. This passage furnishes the chief links in the ancestry of David, but it is by no means complete: three centuries elapse between Ram son of Hezron and Nahshon son of Amminadab, whose leadership “of the people of Judah” dates to the days of Moses in the desert (Ex 6:23; Nu 1:7; 2:3) and whose son Salmon married Rahab the prostitute after the fall of Jericho (Mt 1:5).

11–12 Another three centuries elapse before we reach Boaz the husband of Ruth, who were the grandparents of Jesse the father of David.

13–15 These verses supplement 1Sa 16:6–9 on Jesse’s family. Following his sixth son, Ozem, this source mentions another brother (1Sa 16:10; 17:12) before David, but he is not named; he may have died soon after these events.

16–17 The genealogies of these four warriors, made famous under their half-uncle David (cf. 2Sa 2:18–19; 19:13), are drawn from 2Sa 2:18 and 17:25; but apart from this latter passage, we would not have known that their mothers, Zeruiah and Abigail, were step-daughters of Jesse, born to David’s mother by her presumed earlier marriage to Nahash.

18–19 The remainder of ch. 2 (vv.28–55) tabulates the descendants of the other sons of Hezron, through lists that have not been preserved elsewhere in Scripture. Some of the names that follow designate whole communities that sprang from his line; e.g., Tekoa (v.24), Beth Zur (v.45), Kiriath Jearim, Bethlehem, or Beth Gader (vv.50–54). Hezron’s son Caleb is not to be confused with Moses’ spy of the same name (1:15), who appeared three hundred years later.

20 Bezalel is recalled as the Calebite whose craftsmanship, given by the Spirit of God, equipped him to superintend construction for the Mosaic tabernacle (Ex 31:2–5; cf. 2Ch 1:5). An interval of centuries seems again to separate his father, Uri, from their ancestors, Caleb’s son Hur. The last named should thus be distinguished from their contemporary, the leader Hur, who joined Aaron in upholding the hands of Moses (Ex 17:10, 12; cf. 24:14).

21–22 The Transjordanian conquests of Jair, a later descendant of Hezron’s son Segub, also occurred under Moses. These are documented in Nu 32:41 and Dt 3:14, where Jair is called a son of Manasseh, through Segub’s mother, the daughter of Makir (vv.21, 23), rather than through his father, Hezron.

23–24 The total of sixty towns includes Jair’s twenty-three plus a remaining thirty-seven at Kenath (Nu 32:42); they may also be combined under Jair’s name (Dt 3:4, 14; Jos 13:30). Their loss to the Arameans may have occurred in the early ninth century, since by King Ahab’s day (853 B.C.) Ramoth Gilead lay on the frontier (1Ki 22:3).

25–40 The descendants of Jerahmeel (vv.25–41) came to occupy a broad area in the Negev of southern Judah. Some critics dismiss the Jerahmeelites as aliens; but while they can be mentioned with the Kenites (1Sa 30:29), who had a truly foreign origin, and can even be described in parallel with Judah (1Sa 27:10), Jerahmeel himself is stated to be the firstborn son of Hezron, into whose clan foreign elements may subsequently have come to be incorporated. Sheshan’s daughter who married Jarha (v.35) is probably the Ahlai mentioned in v.31.

41 The Elishama here named represents the twenty-third generation after Judah. With a lapse of some eight hundred years, this would bring us to about 1100 B.C., or to the generation of Jesse the father of David. Proposed identifications of Elishama with the priest of that name (2Ch 17:8), in about 850 B.C., are thus unlikely chronologically and impossible because of the latter’s tribe (Levi, not Judah).

42–46 The closing verses of the chapter revert to the family of Caleb. The line of descent shows that individuals are intended, though their associated groups did occupy such centers in Judah as Hebron, Mareshah, and Ziph.

47 The relationship of the six sons of Jahdai to Caleb is not given.

48–49 Caleb’s “daughter” Acsah was only a distant descendant of Caleb the son of Hezron, though she was an immediate daughter of Caleb the son of Jephunneh, the faithful spy (listed in 4:15). She is remembered as the bride of Othniel, the first of the judges (Jdg 3:9–11), having been promised to him for his conquest of Debir (Jos 15:15–19; Jdg 1:11–15).

50–53 Ephrathah (v.50) is a variant form for the name of Caleb’s wife Ephrath (v.19).

54–55 The Kenites were originally a foreign people (Ge 15:19), some of whom, by marriage or by adoption, became incorporated into the tribe of Judah (cf. the instance of the family of Hobab, the brother-in-law of Moses, Nu 10:29–32; Jdg 1:16, 4:11). There is always room among the people of God for those who come to him by faith (Ex 12:38, 48; Eph 2:19). The clan of Recab later included the reformer Jehonadab (2Ki 10:15, 23), who preserved the purity of his descendants by retaining their primitive forms of nomadic life (Jer 35:6–10).

2. The family of David (3:1–24)

This chapter chronologically follows ch. 2, which had traced several of the branches of the tribe of Judah down to the time of Israel’s united kingdom. At this point, however, the record restricts itself to the royal line of David (2:15) and carries it through five centuries, to about 500 B.C. The prophecy of Jer 22:30 in 597 had made it clear that no purely human descendant of his line could ever legitimately again occupy the throne; and when the Persians authorized the restoration of the Jewish community from Babylon in 538, they permitted no kingship.

Yet the Davidic family maintained its importance. It was represented in the return to Palestine, it supplied civic leaders for Judah (including her first two governors, down through 515 [Ezr 5:2, 15]), and Zechariah prophesied that it would continue to do so (Zec 12:7–10). This house held the ultimate hope of Israel. The Messiah would someday arise from it, that Son of David whom postexilic prophecy identified as more than human. He would be God’s “fellow” (Zec 13:7, KJV), pierced as a man but acknowledged as deity (12:10). He would bring redemption from sin (13:1) and God’s kingdom on earth (14:9).

1–9 This listing of David’s children repeats and supplements 2Sa 3:2–5; 5:13–16; and 13:1. Daniel, his son by Abigail, is named, alternatively, Kileab in 2Sa 3:3.

The list of younger sons (vv.5–8) is repeated in 14:3–7. Solomon was chosen to succeed David (22:9) rather than one of his older brothers, at least three of whom were murdered in inner-family struggles. The third son listed in v.6 (omitted in 2 Samuel) is Elpelet (cf. 14:5); his early death may account for David’s choice of a longer form of this same name for his younger brother, Eliphelet (v.8). The next to last son (v.8) was originally named Beeliada (14:7), meaning “The (divine) Master knows.” But this was changed (both here and in 2Sa 5:16) to Eliada (“God knows”), to avoid the idolatrous implications of Baal. In 2Sa 13 is a report of the scandal of Tamar’s rape by her half-brother Amnon and the vengeance by her brother Absalom.

10–16 The remainder of the chapter lists the Davidic line of succession, first to the throne (vv.10–16, following the order that is in 1 and 2 Kings), and then, during the Exile and beyond, to such nonkingly leadership as they may have enjoyed (vv.17–24, which are new).

Azariah (v.12), as used here (and in 2 Kings), represents the throne name of Uzziah, as is used elsewhere in Chronicles (cf. Isa 6:1). Similar is the name Shallum (v.15; cf. Jer 22:11) for Jehoahaz (2Ch 36:1–4; 2Ki 23:31–34). Though younger than Jehoiakim, he was preferred to him for the throne, following Josiah’s death in 609 B.C; and though older in fact than Zedekiah (2Ch 36:2, 11), he is here listed after him, probably because his reign was so much shorter. Josiah’s firstborn son, Johanan, is not mentioned elsewhere and may have died young.

The name Jeconiah (v.16; shortened to Coniah in Jer 22:24, 28; 37:1; see NIV note) means “Establishes (does) the LORD”; it usually has its elements transposed into Jehoiachin (2Ch 36:9–10; 2Ki 24:8–17), which means “The LORD establishes.”

17 Shealtiel was the physical son of Neri (Lk 3:27) but must have become the legal (adopted) son of Jeconiah soon after the latter’s captivity in March 597 B.C., since five out of the seven sons are mentioned on a Babylonian ration receipt dated to 592.

18 Shenazzar has been equated with Sheshbazzar (“prince of Judah,” at the return in 538–537, Ezr 1:8); both seem to be shortened forms of the Akkadian Sin-aba-usur.

19–20 Shenazzar was succeeded as the first Persian governor of Judah (Ezr 5:4, 16) by his nephew Zerubbabel (2:2), physically the son of his next older brother Pedaiah, but reckoned as the legal son of the oldest brother, Shealtiel (Ezr 3:2, 8; Hag 1:1, 12; Mt 1:12; Lk 3:27). Shealtiel may have died without having children, so that his brother would have raised up seed to his name according to the custom of the levirate (Dt 25:5–10). The authenticity of many of the names that follow is confirmed by archaeological evidence from sixth and fifth centuries seals and letters.

21 The Hebrew text does not have “and” to introduce “the sons of Rephaiah, of Arnan . . .” These are not stated to be further grandsons of Zerubbabel but are presumably contemporaries of Jeconiah the captive whose relationship to him has not been preserved.

22–24 Since only five names now appear in the list of Shemaiah’s six sons (v.22), one must have fallen out.

3. Other clans of Judah (4:1–23)

None of the genealogies of Judah recorded here appears elsewhere in Scripture. Verses 1–8 supplement ch. 2 on the clan of Hezron, a son of Judah’s fourth son Perez. In particular they concern four sons of Hur (cf. v.4), who were grandsons of Hezron’s third son Caleb, and eight branches of his fifth son Ashhur. Verses 9–20 describe the situations of eight leaders in Judah: Jabez, Kelub, Kenaz, Jehallelel, Ezrah, Hodiah, Shimon, and Ishi. However, while they too might be classified under Hezron, their exact relationship to him remains unknown, either because of gaps in Ezra’s own sources or because of a lack of care in subsequent scribal transmission. Verses 21–23 outline the clan of Judah’s third son Shelah (cf. 2:3).

1 Author Ezra expected his readers to recognize (from 2:5, 18, 50) that the five descendants of Judah, from Perez to Shobal, were not brothers but successive generations. “Carmi” must therefore be a scribal error (caused by 2:7?) for Caleb (Kelubai; cf. NIV note on 2:9).

2 These data supplement 2:52 on Hur’s first son Shobal, where Haroeh had appeared as a variant for Reaiah.

3–5 Similarly v.3 on Hur’s fourth son and v.4 on his fifth and sixth sons supplement 2:19; and vv.5–8, on the family of his uncle Ashhur, supplement 2:24.

6–8 “Haahashtari” is not a proper noun but is adjectival and designates “one descended from A(ha)shtar.”

9–10 Jabez’s prayer of faith became an occasion of grace, so that God kept and blessed him, rather than causing him “pain” (“Jabez” means “he causes pain”).

11–12 Ir Nahash (v.12; cf. NIV note, “city of copper,” or “coppersmith”) is Khirbet Na-has, on the west side of the Arabah, south of the Dead Sea.

13–14 Though originally a foreign Kenizzite (whether of Canaan, Ge 15:19, or of Edom, 36:42), Othniel was adopted into Israel’s tribe of Judah and became the first of the judges (see 2:49, 55). He who is adopted into the people of God can even become a leader.

15 Caleb was Othnie’s brother; but he was sufficiently older (Jdg 1:13; 3:9), having belonged to the previous desert generation, among whom he was honored as one of the two faithful spies (Nu 13–14).

16 The settlement of Jehallelel’s descendants, with those of Calebite Mesha, at Ziph (cf. 2:18, 42) in the southeastern part of Judah (Jos 15:24), confirms the preexilic authenticity of Ezra’s source, since in his own day Judah’s southern border failed to reach even to Hebron.

17–20 The wife of Mered intended in v.17 is Bithiah (v.18). Her identification as a daughter of Pharaoh would locate this event during the early part of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt (before 1800 B.C.), the union probably being made possible because of Joseph’s prominence.

21–23 Mareshah, in southwest Judah, experienced dual settlement (cf. v.16), both from these descendants of Judah’s third son, Shelah, and from his fourth, Perez (2:4).

Over long periods Israel’s genealogical clans could be associated with particular places, be organized into particular guilds—whether of linen workers (here), of potters (v.23), or of scribes (2:55)—or be maintained by particular royal patronage (4:23), a situation that has been confirmed archaeologically by means of distinctive pottery marks.

C. Simeon (4:24–43)

Because of their massacre of Shechem (Ge 34:24–30), the patriarchs Simeon and Levi were condemned to have their tribes scattered among Israel (49:5–7). The subsequent faithfulness of the Levites (Ex 32:27–29) converted their situation into one of blessing and of priestly leadership (Dt 33:8–11). But the Simeonites remained accursed (omitted altogether in the tribal blessings of Dt 33). Simeon was granted lands in Palestine only within the arid southwestern portions of Judah (Jos 19:1–9; cf. 15:26, 28–32, where these appear among territories that Joshua had previously assigned to Simeon’s more favored neighbor); and it campaigned cooperatively with Judah in their conquest (Jdg 1:3).

Chronicles records first the primary genealogy of Simeon (4:24–27), then its list of towns (vv.28–33), and finally a summary of two of its later migrations (vv.34–41, 42–43). For after the division of Solomon’s kingdom in 930 B.C., elements of Simeon either moved to the north or at least adopted its religious practices (cf. the inclusion of Beersheba along with the shrines of Ephraim that are condemned in Am 5:5), so that they are counted among the northern tribes (2Ch 15:9; 34:6). Other Simeonites carried on in a semi-nomadic life in isolated areas that they could occupy, such as those noted at the close of this chapter (v.41 dates to Hezekiah, 726–697 B.C.).

24 This list of Simeon’s sons comes from Nu 26:12–13, which reflects Ge 46:10 and Ex 6:15, though with variations in spelling and with the omission of a third son, Ohad. The next son’s name, Jarib, has been corrected by the Syriac to read Jachin, as in the other lists.

25–37 These verses constitute a supplement preserved only in Chronicles. Mibsam and his son Mishma should not be confused with Ishmaelites of the same names (1:29–30).

Beth Biri (v.31) is the Chronicler’s postexilic designation for Beth Lebaoth (Jos 19:6), and for Shaaraim we should read (with Jos 19:6) Sharuhen, a historically significant city located in this area.

38–40 The name Gedor has been emended, with the LXX, into Gerar, a city south of Gaza toward Philistia in the west (cf. 2Ch 14:13–14). Yet the presence of Meunites (see below on v.41) and the direction of Simeon’s other recorded attack, toward Seir (vv.42–43), suggest a Gedor “overlooking the Dead Sea” to the east.

In v.40 the Canaanites, as a branch of the Hamites (1:8), seem to be intended here.

41–43 The Meunites constitute an Edomite tribe; see 2Ch 20:1 (cf. 26:7). The phrase “remaining Amalekites” (v.43) implies some previous avenging work, i.e., of Saul (1Sa 14:48; 15:7) and of David (1Sa 30:17; 2Sa 8:12), against these ancient enemies of God’s people (cf. Ex 17:8–13; Dt 25:17–19). Yet the tribe of Simeon was motivated as well by economic factors of overpopulation (v.38) and shortage of pasture (vv.39, 41).

D. Transjordan Tribes (5:1–26)

Though the OT’s postexilic restoration centered in Judah, the population included elements from all twelve tribes, whose identity the Chronicler was anxious to perpetuate (cf. Ezr 6:17; 8:35). Chapter 5 concerns those once settled east of the Jordan rift. Even prior to Joshua’s conquest of Canaan in the west, Moses’ people had suffered a series of unprovoked attacks from the kings in Transjordan (Nu 21:21–23, 33). But all this had been of God (Dt 2:30) and resulted in the Israelites’ acquisition of the whole territory from the Arnon (midway on the east shore of the Dead Sea) northward, and on through Gilead and Bashan. Moses then granted these areas (Nu 32:33–42), respectively, and at their own request, to Reuben (the subject of 1Ch 5:1–10), Gad (vv.11–17), and half of the tribe of Manasseh (vv.23–24; cf. 7:14–19, on their western half).

The remaining verses of ch. 5 describe an early, joint military campaign (vv.18–22, elaborating v.10)—in which God rewarded their faith and their prayers with a great victory over the Ishmaelites—and their later deportation to Assyria (vv.25–26), as the result of collective apostasy.

1 Reuben’s crime of incest with his father’s subordinate wife Bilhah (Ge 35:22) cost him his rights of the firstborn (49:4), which involved a double portion of inheritance (Dt 21:17). This was transferred to Joseph, first son of Rachel, the wife whom Jacob-Israel loved (Ge 49:25–26; cf. 48:20–22, on Joseph’s double-tribed status, through his sons Ephraim and Manasseh). Joseph’s leadership was first exercised personally (Ge 50:21), then later through Joshua (an Ephraimite), and thus for three more centuries (cf. Jdg 8:1–2; 12:1–6).

2 Yet Judah eventually became strongest: Jacob’s prophecy of this tribe’s preeminence over the other (Ge 49:8), and even of a scepter (v.10), was fulfilled in David’s kingship (2Sa 5:1–3; cf. 7:8), which entailed the effective rejection of Joseph (Ps 78:67–70), and was rendered eternal through David’s Greater Son, who was also God’s Son (2Sa 7:14), Jesus the Messiah (Mt 1:1).

3 Reuben’s four sons are listed just as in the Pentateuch (Ge 46:9; Ex 6:14; Nu 26:5–6), but Ezra’s data in the rest of the chapter are unique to Chronicles.

4–5 The text does not say from which of Reuben’s sons Joel was descended.

6 The Assyrians exiled the Israelite border tribes in 733 B.C. (vv.22, 26; 2Ki 15:29).

7–9 The settlement in the areas mentioned here (named also in Nu 32:38) preceded 850 B.C., since they are claimed as Moabite in Mesha’s inscription, as well as subsequently (Jer 48:1, 22; Eze 25:9).

10 Saul himself fought in Transjordan (1Sa 11:1–11), but with the Ammonites instead of the Hagrites, and at Jabesh Gilead, not far east of the river.

11 The plains of Bashan, extending from the gorge of the Yarmuk and thence north and east of Galilee, pertained to Manasseh (v.23). By wide scattering Gad’s outposts reached them; but its major settlements lay in Gilead, south of the Yarmuk (cf. v.16).

12–15 The Gadite Buz is not otherwise known and is not to be confused with Abraham’s nephew, Buz, the son of Nahor (Ge 22:21).

16 Sharon refers here, not to the coastal plain north of Philistia (Jos 12:18), but to broad pasturelands somewhere in Transjordan.

17 The reigns of Jotham and Jeroboam II extended from 793 to 731 (to 753, for the latter, in Israel; and 750–731, for Jotham, in Judah).

18–19 Hagar was the mother of Ishmael, whose twelve sons, in turn, included Jetur (NT “Iturea,” Lk 3:1) and Naphish (Ge 25:12, 15; cf. the presence of such Arab tribes with Moab in Ps 83:6), Though “the battle was God’s” (v.22), his people still had to initiate it!

20–22 God’s divine presence did not mean that his people would not have to cry out in the battle; but when they did, he vindicated the prayers of those who trusted in him. The great numbers taken, including one hundred thousand people, shows this to have been no mere raid but a total, permanent occupation.

23 Senir was the Amorite name for Mount Hermon (Dt 3:9).

24–26 Since Pul was the private name of Tiglath-pileser III prior to his accession in 745 B.C., the NIV has properly translated: “God stirred up the spirit of Pul . . . that is, Tiglath-Pileser.” The Lord used even Assyrians to accomplish his purposes (Isa 10:5–6).

E. Levi (6:1–81)

The tribe of Levi became Israel’s hereditary religious leaders (see comments on 4:24–43). Ezra took special pains to ensure their presence within the second return, which he led back in 458 B.C. (Ezr 8:15–20); and from the very start, postexilic Judah depended on their proper service (1:5; 3:8; 6:18–20). Levi included the priesthood, so that Ezra himself was careful to present his Levitical credentials (7:1–5), going back to Aaron, Israel’s initial high priest. Authentic genealogy, indeed, was essential for investiture (cf. 2:59–63)—hence the practical relevance of this chapter to the Chronicler’s own day.

Yet a deeper and more abiding significance lies in the nature of Israel’s priesthood as types. Their service in the sanctuary reflected a heavenly pattern (Ex 25:9, 40; Heb 8:2, 5); and the atoning acts performed by Aaron’s descendants were but foreshadows of that ultimate sacrifice, accomplished by Jesus Christ, our Great High Priest, by the offering up of himself once and for all (Heb 9:14, 24–25). Chapter 6 commences with Pentateuchal citations and concludes with territorial lists taken from Joshua, but it consists primarily of materials not found outside Chronicles.

1–2 Levi’s sons always appear in this order based on age (Ge 46:11; Ex 6:16; Nu 3:17; 26:57). Kohath is singled out (Ex 6:18; Nu 3:19) as the ancestor of the priestly group.

3 This Amram is a family ancestor, separated by some 250 years and nine generations from the father of Moses and Aaron (cf. Ex 6:20; Nu 26:59) and from about five thousand Amramites living in their day (cf. Nu 26:62). Of the sons of Aaron (derived from Ex 6:23; Lev 10:1; Nu 3:2; 26:60), the first two died for their sacrilege (Lev 10:2; Nu 26:61); and the succeeding line of priests is here traced only through Eleazar (cf. Ex 6:25; Nu 25:7).

4–7 Some links have been omitted from the priestly genealogy: the twenty-one generations after Eleazar, down through Jehozadak at the Exile (v.15), span more than eight hundred years; and forty years per generation seems overly high. The list includes no descendants of Eleazar’s younger brother, Ithamar, who held office during the last of the judges and the early kingdom—e.g., Eli, Phinehas III, Ahitub, Ahimelech I (= Ahijah?), Abiathar, and Ahimelech II (1Sa 14:3; 22:20; 2Sa 8:17). Other preexilic high priests are not listed either.

8 Serving under David in 1000 B.C. was Zadok (2Sa 8:17; 15:24), son of Ahitub II (not to be confused with Ahitub I, noted above as the grandfather of David’s other priest, Abiathar, who was of the Ithamar branch). Some critics reject Zadok’s Hebrew genealogy and label him a Jebusite, perhaps to be associated with Melchizedek (see Ge 14:18).

9 Zadok’s grandson Azariah I became high priest under Solomon, 970 B.C. (1Ki 4:2).

10 Azariah II, “who served as priest in the temple Solomon built,” would thus belong later and, allowing for gaps to include the long-lived Jehoiada (2Ch 24:15), could be the high priest who resisted Uzziah’s trespass against the temple and its priesthood in 751 (26:17).

11–15 Hilkiah (v.13) discovered the Book of the Law of the Lord given through Moses (2Ch 34:14), the event that led to Josiah’s reformation of 622. Seraiah (v.14) suffered martyrdom to the Babylonians in 586 (2Ki 25:18); but his son Jehozadak was father of Jeshua (or Joshua), Judah’s famous high priest of the return from captivity fifty years later (Ezr 3:2; 5:2; 10:18; Hag 1:1; Zec 3:1; 6:11).

16–30 The divisions of the three Levitical clans are those found in Ex 6:17–19 and Nu 3:18–20 (cf. Nu 26:58). Since Korah (v.22) is known to have come from the clan-patriarch Kohath through the branch of Izhar (vv.37–38), Amminadab could possibly be an alternative name for it. Korah was the leader who rebelled against Moses and whom the earth swallowed (Nu 16:32). Assir, Elkanah I, and Ebiasaph were then his sons (Ex 6:24) and not successive generations.

Uriel (v.24) may be the Levite who led the entire Kohathite clan in David’s day (15:5). Comparisons of v.25 with vv.35–36 show that this is not the Elkanah of v.23 but rather the great-great-great-great-grandson of his brother Ebiasaph, i.e., Elkanah II.

Zophai, Nahath, and Eliab (vv.26–27) appear to be variant names for Zuph, Toah, and Eliel (vv.34–35). The Levite Elkanah IV is the husband of Hannah and the father of Samuel, the judge and prophet.

31–32 In his zeal for the proper worship of God, Ezra makes affirmations about the Davidic musicians (cf. Ezr 2:41). The “Tent of Meeting” was for God’s meeting Israel (Ex 29:42–43), not for the people with each other!

33–38 David’s musician Heman, 1000 B.C., is eighteen generations removed from Moses’ adversary Korah, in 1445.

39–43 The name of Asaph’s ancestor Shimei (v.42), the immediate son of Gershon (v.17), seems here to have been transposed with that of Jahath. The similarity then of five out of the six names of his descendants—from Jahath through Ethni (v.41)—to those of his brother Libni—Jehath to Jeatherai (vv.20–21)—has led some interpreters to assume that this must be an erroneous doublet, drawn from a single tradition. Yet 23:10 confirms the existence of Jahath as a legitimate, parallel branch of Gershon’s younger son Shimei; and a deliberate reuse of names among brothers’ sons is not infrequent (cf. the name Mahli, vv.19, 47, or how the Mahli of v.19 took for his child the name of this same older son of Gershon, i.e., that of his cousin Libni, v.29).

44–53 Ethan and Kishi (v.44) appear also as Jeduthun and Kushaiah (15:17). Verses 50–53 repeat vv.4–8 on the priestly line from Aaron, down to Zadok and Ahimaaz. This confirms that the Zadokite priests, alone among the Levitical divisions in David’s day, had the authority to make a sacrificial atonement (v.49). It also furnishes a transition to the subject of the priestly cities that follows.

54–55 The remainder of ch. 6 lists the forty-eight towns that were assigned to the various branches of the tribe of Levi. As Jacob had predicted, they did become scattered among Israel (Ge 49:7). The list is taken from Jos 21. Ezra’s reference to “the first lot,” which went to the Aaronic priests, confirms the record that when Joshua distributed the land in 1400 B.C. among the western nine and one-half tribes and Levi, he accomplished it by means of a lottery (Jos 4:2; 21:10).

56–60 The lands of Hebron (v.56) had been promised to Caleb by both Moses and Joshua (Jos 14:6–15). On the six cities of refuge (v.57), see Nu 35; Dt 19:1–10; Jos 20. Hilen (v.58) is the Chronicler’s postexilic name for Holon (Jos 15:51; 21:15).

61–81 The nonpriestly Kohathites (v.61) also received towns out of Ephraim (v.66) and Dan (Jos 21:5, specifically Eltekeh and Gibbethon, 21:23). The latter are required in v.68 to make up the subtotal of ten, where they are missing due to textual corruption. Jokmeam (v.68) is the Chronicler’s postexilic name of Kibzaim (Jos 21:22).

F. Benjamin and Five Other Tribes (7:1–9:44)

1. Summaries (7:1–40)

Just as in the case of the two and one-half tribes of Transjordan (cf. the introductory discussion to 5:1–26), Ezra was concerned to perpetuate clan frameworks for other members of the former northern kingdom. Some representatives had associated themselves with Judah at the Fall of Samaria in 722 B.C. (cf. 2Ch 30:1–2), or even previously (11:13–16); and Josiah’s expansion a century later embraced many more (34:6; cf. 1Ch 9:1). Others regained their place among God’s people during the Exile of 586–538 (cf. Eze 37:15–23) and were able to return to Judah under Zerubbabel or under Ezra himself (cf. the casual allusion in Lk 2:36 to Anna of the tribe of Asher, one of the “ten lost tribes”). In the buffer zone between north and south lay Benjamin, which could include even the northern religious center of Bethel (Jos 18:22). It is summarized in ch. 7, along with the Ephraimite tribes, but is treated in greater detail in chs. 8 and 9 as Judah’s major ally, both in the preexilic kingdom and postexilic restoration (1Ki 12:21, or the “two-twelfths” implied in 11:30–31, and Ezr 4:1).

This chapter outlines the clan structure that characterized Benjamin and five other tribes. Its sources are Ge 46 and Nu 26, but most of the later genealogies and other data lack biblical parallels. No mention is made of either Dan or Zebulun. Possibly these tribes had little influence or relevance among the Jews who made up Ezra’s community.

1 The sons of Issachar appear as listed in Nu 26:23–24, with Puah as a variation on Puvah. Issachar’s sons are also listed in Ge 46:13 and Nu 26:24.

2 Among the valiant descendants of Tola may have been the later judge who bore that clan name (Jdg 10:1).

3–5 For Izrahiah and his four sons, even with “many wives,” to have “36,000” warriors seems unlikely, as does the total of 145, 600 for just one tribe of the twelve. This appears to be the first of nine passages in Chronicles where “thousand”) might better be translated as “chief” (a similar Hebrew word). Hence we should read in v.2: 22 chiefs, 600 (men); in v.3: 36 chiefs; and in v.5: 87 chiefs.

6 Among the sons of Benjamin, Bela and Beker correspond to Ge 46:21 (cf. Nu 26:38). The third, Jediael, is not mentioned elsewhere. Other sons appear in 8:1–2.

7–12 The figures, as in v.3, should best be read: v.7, as 22 chiefs, 34 men; v.9, as 20 chiefs, 200 men; and v.11, as 17 chiefs, 200 men. Ir and Aher (v.12) may be shortened forms for the names of Bela’s youngest son Iri (v.7) and younger brother Aharah (8:1; cf. Nu 26:38).

13 Naphtali’s sons correspond to those listed in Ge 46:24 and Nu 26:48–49, with minor changes in spelling. Bilhah was the servant of Rachel and the mother of Naphtali (Ge 30:3–8).

14 That Manasseh had an Aramean concubine may have reminded Ezra’s readers of the racially mixed Samaritans in their own day (2Ki 17:24, 29; Ezr 4:2–3). As appears from the more complete record of western Manasseh in Nu 26:29–33, Asriel and Shemida (v.19) were the immediate sons of his grandson Gilead (cf. Jos 17:2).

15–19 Zelophehad (v.15) came three centuries later. His was the case raised by his daughters that prompted Moses’ laws about female inheritance rights (Nu 26:33; 27:1–11; 36:1–12).

20–24 Of Ephraim’s four sons noted in vv.20–21, 23, only Shuthelah had been recorded previously (Nu 26:35); Ezer and Elead had probably joined the families of their grandfather Joseph’s brothers, who had settled in Goshen, only to be slain there on the northeastern border of Egypt by Palestinian raiders who came down from their birthplace in Gath.

25–29 Joshua is listed eight generations after Rephah. Taking Rephah’s father as Ephraim’s fourth son Beriah (v.23), we perceive Joshua’s birth (c. 1500 B.C.; cf. Jos 24:29) to have been eleven generations after Joseph’s, corroborating the approximately four-century interval that separated these two leaders.

30–40 The list of Asher’s children plus two grandsons reproduces Ge 46:17 (cf. Nu 26:44–46). Shomer’s brother Helem (v.35) appears in v.32 as Hotham. Father-son sequences between verses suggest that Ulla (v.39) may be a variant name for Ara in v.38. In v.40 the numeral “thousand” should probably be read “chief”; hence, 26 chiefs (see comment on v.3).

2. Benjamin (8:1–40)

First Chronicles 8 forms a major supplement to the summary of Benjamin given in 7:6–12. Its opening verses, however, on his first generations in Egypt, are based on Nu 26:38–40 (rather than on Ge 46:21, as in ch. 7). Verses 6–28 are almost without biblical parallel; they outline the genealogy of two family groups as these developed after the Hebrew conquest and resettlement of Canaan: the Benjamite household of Ehud, Israel’s second judge (vv.6–7), and that of Shaharaim, some of whose great-grandchildren lived in the neighborhood of Jerusalem (v.28). The remainder of the chapter concerns the relatives who lived near them and who formed the ancestry of Saul, part of whose descent had been given in 1 Samuel.

Chronicles elaborates on this material, not simply because of the significance of King Saul and his family, as it continued a dozen generations after him, but primarily because of the importance of Benjamin as a tribe, which ranked second only to Judah in postexilic society, and because of the status it provided for many within its clan framework (cf. introductory discussion on ch. 2, and Ne 11:4, 7, 31, 36).

1–2 The name of Benjamin’s third son, Aharah (Aher, 7:12), corresponds to Ahiram in Nu 26:38 (Ehi, in Ge 46:21), as do also those of the grandsons Addar (= Ard) and Naaman (v.3).

3–5 The second name in the list of Bela’s sons (Gera) reappears as the seventh name (v.5); the former may have died prematurely.

6–7 Some five hundred years separate the latter Gera from his descendant Ehud, the left-handed Benjamite judge (Jdg 3:15). The nature of the civil rivalry that led Ehud’s son Gera to deport his own clansmen remains unknown.

8–13 Though Shaharaim’s movement to Moab seems to locate him in Palestine in Ehud’s general period (cf. the Benjamite towns mentioned in vv.12–13), his exact ancestry is lacking. The divorce of his first two wives demonstrates even further the moral deterioration of Israel during c. 1300 B.C. (cf. the previous Benjamite outrages condemned in Jdg 19:22–28; 20:12–14). The victory over the men of Gath (v.13) preceded their major Philistine reinforcement in 1200 B.C.

14–27 Meshullam, Heber (v.17), Ishmerai (v.18), and Shimei (v.21) seem to be variants for the names of Elpaal’s sons Misham, Shemed, Eber, and Shema, as listed earlier (vv.12–13).

28 The phrase “all these” then identifies Beriah’s and Shema’s sons (vv.14–16, 19–21), brothers (vv.17–18), and grandsons (vv.22–27) as the ones living about Jerusalem.

29–32 When Mikloth and his son Shimeah (v.32) are said to live not only (following the lit. Heb.) “over against” their brothers (Mikloth’s immediate family, in vv.30–31), but also “with” their relatives, we conclude that Mikloth’s otherwise unidentified father Jeiel (cf. 1Sa 9:1 and the variant form, Abiel) should be grouped with the sons of Beriah and Shema.

33 Jeiel’s fifth son, Ner, was the grandfather of Saul, the first king of Israel (1043–1010 B.C.), and also the father of Abner, Saul’s military commander and uncle (1Sa 14:50–51). Abinadab (1Sa 31:2) appears elsewhere (1Sa 14:49) as Ishvi. Abinadab’s brother’s name, Esh-Baal (meaning “man of the [divine] Master”), is changed throughout 2Sa 2:8–4:12 to Ish-Bosheth (“man of shame”); for the Hebrew word baal could be treated as a proper noun designating the shameful idol of that name. 34 Similarly Merib-Baal (“warrior of the Master”) appears in 2Sa 4:4–21:7 as Mephibosheth (“one who scatters [?] shame”).

35–40 The warriors’ “grandsons” (v.40) represent the thirteenth generation after Mephibosheth, who was five at the death of Saul and Jonathan in 1010 B.C., which brings us to the Exile of 586.

3. Jerusalem’s inhabitants (9:1–44)

Chapter 9 continues the Chronicler’s discussion of preexilic Benjamin (begun in 7:6) by cataloging the family groups that lived in Jerusalem just prior to its capture and destruction in 586 B.C. In addition to Benjamin (vv.7–9), these included clans from Judah (vv.4–6) and especially from Levi because of its key functioning in the temple services: whether from among the priests (vv.10–13), the nonpriestly Levites in general (vv.14–16), or the more specialized gatekeepers (vv.17–19). This in turn leads into a description of their duties (vv.20–34). Jerusalem did, however, lie within the tribal boundaries of Benjamin (Jos 18:16, 28), and it had already received some discussion in the preceding chapter (8:28, 32); hence its inclusion at this point. Such information about former population groups and activities, in what was still the nation’s capital city, was of prime importance to Ezra and his colleagues in their efforts to restore legitimate theocracy to Judah in their own postexilic situation.

1 This transition verse shifts the reader’s attention away from the tribal registers that have gone before. “The book of the kings” designates a court record now lost (see the introduction).

2 The NIV’s phrase “the first to resettle” represents words that are, literally, “the dwellers, the first ones.” In the present context the event that separates the Chronicler from “the first ones” is defined as the Babylonian captivity (v.1); hence the dwellers should probably be understood as the former, preexilic Jerusalemites (cf. the introduction to this chapter).

The “temple servants” (GK 5987) were literally “given ones.” They might consist of captives who had been spared but enslaved to temple service. Early Hebrew examples include certain Midianite women (Nu 31:35, 47) or the people of Gibeon (Jos 9:22–23), but their organization as a class is credited to David (Ezr 8:20).

3 Individual Jerusalemites who had come from Ephraim or other northern tribes receive no further mention, since the list that follows cites only major clan leaders.

4–9 For “Shilonites” (v.5), read Shelanites, as in Nu 26:20, since Perez (v.4), Shelah, and Zerah (v.6) make up the divisions of Judah (2:3–4).

10–13 Jedaiah, Jehoiarib, and Jakin, with Malkijah and Immer (v.12), are the names of the second, first, twenty-first, fifth, and sixteenth of the twenty-four priestly courses established by David (24:7–18), rather than names of individuals. The fact that Azariah IV (v.22) is the son of Hilkiah (see 6:13) dates this listing to shortly after 622 B.C.

14–16 Shemaiah came from Merari, the third of the three Levitical clans. Mattaniah belonged to the first, Gershon, through Asaph, one of David’s chief musicians. Obadiah was again of Merari, through the chief musician Jeduthun (= Ethan; cf. 6:44), while Berekiah’s ancestor Elkanah bears a frequently reappearing Kohathite name.

17–18 Since the temple faced east, the “King’s Gate” was the main gate (cf. Ac 3:2, in NT times), i.e., the king’s entrance (Eze 46:1–2) and most honored station. Ezra’s phrases “camp” of the Levites and God’s “Tent” (v.19; cf. NIV note) recall how Levi once encamped on the four sides of the tabernacle (Nu 3:25–38).

19–20 Though Korah had been slain (see 6:22), his line continued. Coming from Kohath—the second clan but also that of Moses, Aaron, and the priests—the Korahites were even honored, by appointment as gatekeepers under Aaron’s faithful grandson, Phinehas I, on whom God bestowed the Levitical covenant of peace (Nu 25:11–13). Their status continued, through Kore, whether denoting Korah’s immediate grandson of this name (1Ch 26:1) or a later Kore in 725 B.C. (2Ch 31:14), down to this Shallum a century later.

21 Since both Meshelemiah and Zechariah served under David (26:8–11), this “Tent of Meeting” (cf. 6:32) would seem to refer to the curtained form of God’s house (16:1; 17:1; cf. 22:1 and Ps 30 title) erected prior to Solomon’s permanent temple (see v.19, NIV note).

22–24 It was appropriate that Samuel, himself a Korahite (6:27) and one of the doorkeepers in his youth (1Sa 3:15), should have anticipated David in their final organization (1Ch 26). The way Israel could commit to them “their positions of trust” indicates something of how the righteous live by faith, or trust, in God (Hab 2:4; Ro 1:17).

The number of their chiefs could vary: 94 under David (26:8–11); compare 139 among the first return (Ezr 2:42) and 172 under Nehemiah (Ne 11:19).

25–29 Twenty-four guard stations (26:17–18) and 216 chosen gatekeepers (212, v.22, plus the 4 leaders of vv.26–27, who stayed permanently in Jerusalem) works out exactly to nine people for each post. If we assume eight-hour shifts, this would require seventy-two men on duty, one week out of every three; twelve-hour shifts would require forty-eight on a week’s duty, once every four or five weeks.

30 Reference seems to be to spices used for the holy anointing oil, for those who mixed it were a closely restricted group (Ex 30:33, 38).

31 “The offering bread” refers to the flat cakes that were used in the grain offerings (Lev 2;6:14–18; 7:9–10).

32 “The bread” refers to “the bread of the Presence” that was set out in rows on the golden table to symbolize the communion of the redeemed with God (Lev 24:5–6).

33 The musicians mentioned here are the leaders named in vv.14–16.

34 This verse then sums up all the Levitical inhabitants of Jerusalem (vv.10–33).

35–44 The rest of ch. 9 reverts to reproducing the lines of Benjamin that lived near Jerusalem. It virtually repeats 8:29–38 on the family of Saul; but its purpose here is to introduce the tragic conclusion to his reign (ch. 10).

II. The Reign of David (10:1–29:30)

A. Background: the Death of Saul (10:1–14)

Having established Israel’s historical setting and ethnic bounds in the preceding genealogies (chs. 1–9), the Chronicler now enters his main subject, the history of the Hebrew kingdom, with its theological conclusions. His central character is David, on whom the remainder of 1 Chronicles focuses (chs. 10–29). David’s devotion led him to set up the institutions of public worship that Ezra was so eager to maintain. David’s heroic personality exemplifies the success that God bestows on those who trust in him. His posterity, moreover, constitutes the ruling dynasty of Judah throughout the rest of its independent history (the content of 2 Chronicles) and would bear its ultimate fruit in the eternal kingdom of Jesus the Messiah. Practical aims like these also explain why Ezra omitted the less edifying events of the reign of Saul; for he moves directly from the king’s Benjamite genealogy (9:35–44) to his death (ch. 10), which precipitated David’s rise to the throne (v.14). First Chronicles 10:1–12 derives directly from 1Sa 31, with slight differences in the choice of the details described; vv.13–14 then point up the chapter’s negative doctrine: God condemns those who forsake him to failure.

1 The Philistines were a Hamitic people, but of Minoan background rather than Canaanite (see on 1:12). Before the year 2000, some had settled on the southern coast of Palestine (the very name of which means “Philistine land”) and encountered Abraham (Ge 21:32; cf. 26:14). They remained after Joshua’s conquest in 1400 (Jos 13:2–3) and only temporarily lost certain of their cities to Judah (Jdg 1:18). Shamgar’s skirmish with them in 1250 (3:31) was successful but simultaneously demonstrates Israel’s material disadvantage to their presence (cf. 1Sa 13:19–22). With the Fall of Crete to widespread barbarian movements in 1200, the “remnant . . . of Caphtor” (Jer 47:4) reinforced the earlier Philistines on Asia’s Canaanite mainland.

For a century, following a crushing defeat of the Peleset (generally conceded to be the Philistines) by Pharaoh Rameses III, the Philistines seemed content to consolidate their city-states; but then in three waves they almost overwhelmed Israel. The first extended for forty years, including Samson’s time (Jdg 10:7; 13:1; 1Sa 4), but was broken in 1063 B.C. by Samuel at the second battle of Ebenezer (1Sa 7:13); and the second wave, for perhaps ten years, by Saul at the battle of Micmash in 1041 (14:31). Now 1Ch 10, which dates to 1010 B.C., marks the onset of the Philistines’ last major advance and period of oppression, which would be broken some seven years later by David (1Ch 14:10–16).

Mount Gilboa lay at the head of the great east-west Valley of Esdraelon, below Galilee, so that its loss by Israel enabled the Philistines to penetrate to the Jordan and even beyond (1Sa 31:7).

2 On Saul’s sons, see 8:33.

3–4 Saul’s fear of “abuse” (GK 6618), if the Philistines should take him alive (cf. Jdg 16:21), drove him to suicide, which was unprecedented in the OT (though cf. later occurrences in 2Sa 17:23; 1Ki 16:18). This testifies to the Philistines’ cruelty despite material culture (cf. v.9 and today’s use of “Philistine” as a byword for barbarism).

5 The context makes clear that Saul’s death occurred at his own hands (see also comments on 2Sa 1:6–10, where an Amalekite reported to David that he had killed Saul, probably hoping for a reward).

6 Those of Saul’s house who stood with him (“all his men,” 1Sa 31:6) died together at Gilboa; others, however, both of his sons and troops, did survive (1Ch 8:34–40; 2Sa 2:8; 21:8). Alternatively, this may be the Chronicler’s way of intimating the otherwise omitted data in 2Sa 1–4 on Ish-Bosheth.

7–10 According to 1Sa 31:10, the Philistines hung Saul’s body on the walls of Beth Shan, a major city between Gilboa and the Jordan; the deity in whose temple they put his armor was Ashtoreth, goddess of sex and war. Saul’s head was placed in another’s temple, that of the vegetation god Dagon (cf. 1Sa 5:2–5). The validity of the two buildings has been attested archaeologically by the discovery of both temples in Beth Shan’s ruins of this period.

11–12 The men of Jabesh Gilead in Transjordan remained faithful to Saul, their deliverer thirty years earlier (1Sa 11:1–11).

13–14 Saul’s unfaithfulness consisted of disobeying God’s words through Samuel (1Sa 13:8–9; 15:2–3) and of consulting the spiritist at Endor (28:7–13) instead of persevering—he had made some inquiry of him (v.6)—in prayer for divine grace.

B. David’s Rise (11:1–20:8)

In this section, the author covers the period between 1003 and about 995 B.C., during which David rose to the zenith of his power. The seven and one-half years of disputed succession, civil war, and Philistine domination (2Sa 1–4) that followed Saul’s death in 1010 (cf. 2Sa 5:5) are passed over. But they are not denied: Ezra’s observation in the opening verse of the section (11:1), that Israel came to “Hebron” to anoint David, constitutes a tacit recognition of his initial installation there, but only by his own tribe of Judah (2Sa 2:4, 10b); of the rejection of his appeal to the other tribes to the north and east (vv.5–6); and of their eventual choice of Saul’s son Ish-Bosheth, 1005–1003 (vv.8–10a).

Instead, Chronicles amplifies the record of 2Sa 5–10, which includes David’s capture of Jerusalem and its establishment as a new political capital for him and his supporters (1Ch 11–12); his achievement of independence from the Philistines (ch. 14); his return of the ark of the covenant, which made Jcrusalem the religious capital of united Israel (chs. 13; 15–16); and the triumphant advance of his armies in every direction (chs. 18–20). Only the account of David’s personal kindness to Jonathan’s lame son Mephibosheth (2Sa 9) is omitted.

The heart of this section is found in God’s prophecy to David through Nathan (ch. 17): “I have been with you wherever you have gone.. . . I will subdue all your enemies” (vv.8, 10). The Lord’s “great promises” (v.19) applied not only to David, but to “my people Israel” as a whole (v.9)—not only in the early tenth century B.C., but for “the future of the house of your servant” (v.17). Its assurances are applicable to Ezra’s struggling postexilic community; to the present church of Jesus, whom David predicted: “He will be my son” (v.13; cf. Ps 110:1; Mt 22:42–45); and to that yet future kingdom of the Messiah, whose “throne will be established forever” (v.14).

1. David established in Jerusalem; his heroes (11:1–12:40)

The section’s initial subdivision documents David’s ascendancy. Following his consecration as king over a reunited Israel (11:1–3), one of his first acts was to capture and then to strengthen Jerusalem (vv.4–9; cf. 2Sa 5:1–10). The Chronicler then proceeds to describe David’s heroes: “the Three” (vv.10–19), two of the major commanders (vv.20–25), and “the Thirty” (vv.26–47; cf. 2Sa 23:8–39). The concluding list in ch. 12, however, is unique to 1 Chronicles. It describes the military leaders and tribal officers who came over to David before his final anointing and who played a primary role in his eventual elevation to the kingship (v.38). It suggests David’s growing popular support beyond the four hundred men of 1Sa 22:2 (later six hundred, 27:2).

1 The phrase “all Israel” is characteristic of the Chronicler’s concern for the unity of God’s people. Emphasis here falls on the portions of Israel that had so far not recognized David’s kingship.

2 The Lord’s appointment of David dates back some twenty years to his first anointing, in the privacy of his family, by Samuel (1Sa 15:28; 16:1–13). As David then demonstrated his ability for leadership (18:5, 16), he was increasingly recognized as standing in line for the throne (23:17; 25:30), even by Saul himself (24:20; 26:25). At Saul’s death David had received a second anointing, over Judah (2Sa 2:4); and Abner had started the preparation for his total rule (3:10).

3 This third anointing was preceded by a “compact” (lit., “covenant”; GK 1382) before the Lord, by which both king and people acknowledged their mutual obligations under God. Such a “constitutional monarchy” was unique in the ancient Near East, for the only effective curb against despotism is one’s personal belief in God and commitment to his higher kingship. Contrast the reputation for clemency and the religious scruples of even a weak Hebrew monarch like Ahab (1Ki 20:31; 21:3–4, 27–29) with the natural (unrestrained) ruthlessness of his Canaanite wife, Jezebel (21:7–10).

4–5 Allusions to Jerusalem appear first in the Ebla tablets of 2400 B.C. The city is described as Salem in reference to Abraham in 2000 (Ge 14:18) and as Urusalim in the Egyptian Amarna letters, which may confirm the Hebrew conquest in 1400. Jerusalem had led a southern Canaanite alliance against Joshua (Jos 10:1–5), who defeated its army and executed its king (10:10, 26; 11:7, 10). The tribe of Judah overran the defenses of the city itself (Jdg 1:8), but the Jebusites soon reoccupied it. For almost four centuries Judah had been unable to win back Jerusalem and drive out its Canaanite inhabitants (Jos 15:63; Jdg 1:21; 19:10–11), which helps explain the latter’s overconfidence against David (1Ch 11:5; 2Sa 5:6). David had posted notice long before of his intention against the haughty city (1Sa 17:54).

While 2Sa 5:6 identifies the attackers only as “David’s men,” Chronicles includes “all the Israelites” (cf. v.10 and 12:38, which concede the primary role exercised by David’s particular followers).

6 The king’s offer that whoever “leads the attack,” i.e., first penetrated Jerusalem, would become commander over the armies of united Israel may represent an attempt on his part to replace his effective but self-willed nephew Joab, who had been leading the forces of Judah up to this point (cf. 2Sa 3:39). Joab nevertheless retained his post by bravely achieving the initial entrance, ascending a concealed watershaft from the Gihon spring so as to end up within the city walls.

7 David’s relocation to Jerusalem was a strategic move. It provided him not only with an impregnable citadel militarily, but also with a neutral site politically as a capital, lying as it did on the border between Judah and the northern tribes (cf. Washington, D.C.). He called it “The City of David.” Near Eastern conquerors not infrequently named cities after themselves.

8–9 “Terraces” (GK 4864; lit., “Millo”; cf. NIV note) means “filling.” These “terraces” had been built so that the city’s eastern walls could extend far enough down the steep Kidron slope to encompass the Gihon watershaft, and they suffered a continuing need for repair (1Ki 11:27; 2Ch 32:5).

10 The remainder of the chapter is a catalog of David’s mighty men, introduced at this point because of the significant role they played in his rise to the kingship and in his establishment at Jerusalem. Their listing, down through Uriah the Hittite (v.41), corresponds to one of the appendices in 2 Samuel (2Sa 23:8–39), with minor variations. Twelve of their number reappear as commanders of the twelve corps into which David’s troops were later organized (1Ch 27).

11 The hero’s sensational victory was actually over eight hundred men (2Sa 23:8). Three hundred seems to be a scribal error, perhaps influenced by the number that appears in v.20 or by the nature of the numerical symbols employed.

12 David’s greatest champions were “the Three,” though the record of the third, Shammah (2Sa 23:11), has accidentally been dropped.

13–14 After the words “the Philistines gathered there for battle,” we should insert the material supplied in 2Sa 23:9 (following this clause) and on into v.11 (through a similar clause).

15 Next to “the Three” ranked “the Thirty”—which was apparently the original number in this legion of honor among David’s men. Second Samuel 23:24–39 actually lists thirty-seven, including the outstanding “Three” and the two commanders; and 1Ch 11:41b–47 adds sixteen more, as new heroes were added to the group. Which ones of the “Thirty” performed the deed that follows is not stated.

The Valley of Rephaim, where the Philistines encamped, lies southwest of Jerusalem. Its mention connects this event with their first campaign against David (14:8–9), even before his capture of the city. David had thus retreated to his old outlaw stronghold at Adullam (1Sa 22:l; 2Sa 5:17). Its citation constitutes another allusion to David’s difficult rise to power, which the Chronicler never seeks to conceal.

16–18 David poured out the water he had longed for as a libation offering to the Lord (Lev 23:37), showing both how precious he considered his men, who had risked their lives to get it, and how centrally he placed God in his own life.

19 David called the water their “blood,” since life does depend on its presence (cf. Ge 9:4; Lev 17:14; Dt 12:23).