INTRODUCTION

1. Background

The Babylonian exile in the sixth century B.C. was preceded by earlier deportations beginning in the eighth century by the Assyrians from both Israel and Judah. Deportation began with Tiglath-pileser III, who attacked Damascus and Galilee in 732 (2Ki 15:29), carrying off at least 13,520 people to Assyria. Then Shalmaneser V and Sargon II besieged Samaria in 722 (2Ki 17:6; 18:10). Sargon boasted that he carried off 27,290 (or 27,280) persons from Israel, replacing them with various other peoples from Mesopotamia and Syria.

Whereas Israel’s population in the late eighth century B.C. has been estimated at 500,000 to 700,000, Judah’s population in the eighth-to-sixth centuries has been estimated at between 220,000 and 300,000. Jerusalem’s population likely was swelled by refugees from the north when Samaria fell in 722. At the time of Nehemiah, however, the city had contracted to 6,000 persons. Judah had escaped the attacks of Tiglath-pileser III when Azariah (Uzziah) paid tribute to the king, though Gezer was captured. But when Sennacherib attacked Judah in 701 B.C., he deported numerous Jews, especially from Lachish. His annals claim that he deported 200,150 from Judah, but this may be an error for 2,150.

The biblical references to the numbers deported by the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar are incomplete and somewhat confusing, giving rise to conflicting interpretations as to the actual number of Judeans deported. Until 1956 we had no extrabiblical evidence to confirm the attack on Judah in Nebuchadnezzar’s first year. Either in that year or soon after, Daniel and his companions were carried off to Babylon.

In 597 B.C. Nebuchadnezzar carried off “all the officers and fighting men, and all the craftsmen and artisans—a total of ten thousand” (2Ki 24:14). According to v.16, “the king of Babylon also deported to Babylon the entire force of seven thousand fighting men . . . and a thousand craftsmen and artisans.” If these figures represent only the heads of households, the total may have been closer to thirty thousand. On the other hand, Jeremiah enumerates for 597 B.C. but 3,023 captives (Jer 52:28) and for 586 only 832 captives from Jerusalem (v.29). In 582, after the murder of Gedaliah, 745 were deported, for a grand total of 4,600 (v.30). The smaller figures of Jeremiah probably represent only men of the most important families. Depending on one’s estimate of the numbers deported and the number of returning exiles, we have widely varying estimates for the population of postexilic Judah. An estimate of 150,000 is probably correct.

An important difference between the deportations by the Babylonians and by the Assyrians is that the Babylonians did not replace the deportees with pagan newcomers. Thus Judah, though devastated, was not contaminated with polytheism to the same degree as was Israel.

According to the biblical record, the Babylonian armies smashed Jerusalem’s defenses (2Ki 25:10), destroyed the temple and palaces (2Ki 25:9, 13–17; Jer 52:13, 17–23), and devastated the countryside (Jer 32:43), killing many of the leaders and priests (2Ki 25:18–21). The severity of the Babylonian devastation has been amply confirmed by archaeology, evidences of which have been uncovered at such places as Beth-Shemesh, Eglon, En Gedi, Gibeah, and Jerusalem. Thousands must have died in battle or of starvation (La 2:11–22; 4:9–10). After the deportations only the poor of the land—the vine-growers and farmers—were left (2Ki 25:12; Jer 39:10; 40:7; 52:16), occupying the vacant lands (Jer 6:12; see comment on Ezr 4:4). A few refugees who fled to different areas drifted back (Jer 40:11–12). For the next fifty years these people eked out a precarious existence under the Babylonian yoke (La 5:2–5), subjected to ill treatment and forced labor (vv.11–13).

During this time some limited forms of worship were continued in the ruined area of the temple (Jer 41:5). The Scriptures themselves pass over developments in Palestine and stress the contribution of the returning exiles from Babylonia.

In light of the fact that the intellectual and spiritual leaders were the ones who were deported, the Scriptures must reflect the historical situation. Judging from earlier Assyrian reliefs and texts, the men were probably marched in chains, with women and children bearing sacks of their bare possessions on wagons as they made their way to Mesopotamia. The exiled Judean king, Jehoiachin, was maintained at the Babylonian court and provided with rations (2Ki 25:29–30).

After several years of hardship, the exiles made adjustments and even prospered (Jer 29:4–5). They were settled in various communities—e.g., on the river Kebar near Nippur, sixty miles southeast of Babylon (Eze 1:1–3; cf. Ezr 2:59-Ne 7:61). When the exiles returned, they brought with them numerous servants and animals and were able to make contributions for the sacred services (Ezr 2:65–69; 8:26; Ne 7:67–72).

With the birth of a second and a third generation, many Jews established roots in Mesopotamia and wanted to remain there. The spiritual life of the Jewish community in Mesopotamia is documented by Ezekiel, who was in exile either after 597 or 586. Ezekiel 8:1 refers to the prophet “sitting in my house and the elders of Judah were sitting before me” (cf. Eze 3:15; 14:1; 20:1; 24:18; 33:30–33). Deprived of the temple, the exiles laid great stress on the observation of the Sabbath, on the laws of purity, and on prayer and fasting. It has often been suggested that the development of synagogues began in Mesopotamia during the Exile (but see Ne 8:18). The trials of the Exile purified and strengthened the faith of the Jews and cured them of idolatry.

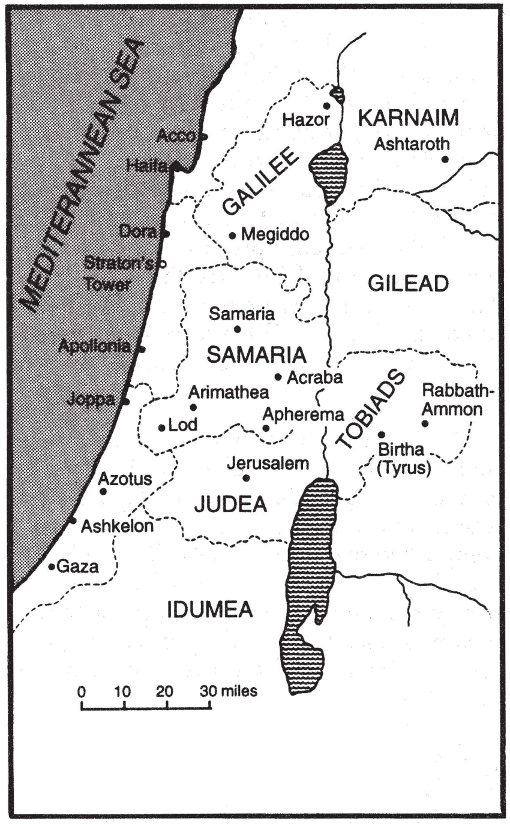

The exiles who chose to return to Judah found their territory much diminished. The tiny enclave of Judah was surrounded by antagonistic neighbors. North of Bethel was the province of Samaria. South of Beth-Zur, Judean territory had been overrun by Idumaeans (cf. on Ezr 2:22–35). The eastern boundary followed the Jordan River, and the western boundary the Shephelah (low hills). The Philistine coast had been apportioned to Phoenician settlers. The Persians did make Judah an autonomous province with the right to mint its own coins.

2. Reign of Artaxerxes I

Nehemiah served as the royal cupbearer of Artaxerxes I (Ne 1:1; 2:1), the Achaemenid king who ruled from 464 to 424. The traditional view places Ezra before Nehemiah in the reign of Artaxerxes I, the third son of Xerxes and Amestris. His older brothers were named Darius and Hystaspes. Their father was assassinated in his bedchamber, between Aug and Dec 465, by Artabanus, a powerful courtier. In the ensuing months Artaxerxes, who was but eighteen years old, managed to kill Artabanus and his brother Darius. He went on to defeat his brother Hystaspes in Bactria. His first regnal year is reckoned from Apr 13, 464 B.C.

From 461 Artaxerxes I lived at Susa. He used the palace of Darius I till it burned down near the end of his reign. He then moved to Persepolis, where he lived in the former palace of Darius I. He completed the Great Throne Hall begun by Xerxes.

When Artaxerxes I came to the throne, he was faced with a major revolt in Egypt that was to last a decade. The Egyptian leaders defeated the Persian satrap Achaemenes, the brother of Xerxes, and gained control of much of the Delta region by 462. The Athenians, who had been at war with the Persians since the latter had invaded Greece in 490, helped the rebels capture Memphis, the capital of Lower Egypt, in 459. This situation may have led the Persians to support Ezra’s return in 458 in order to secure a loyal buffer state in Palestine.

In 456 Megabyzus, the satrap of Syria, advanced against Egypt with a huge fleet and army. During eighteen months he was able to suppress the revolt. A fleet of forty Athenian ships with six thousand men sailed into a Persian trap. In spite of promises made by Megabyzus, the Egyptian leader was impaled in 454 at the instigation of Amestris, the mother of Artaxerxes I. Angered at this betrayal, Megabyzus revolted against the king from 449 to 446. If the events of Ezr 4:7–23 took place in this period, Artaxerxes I would have been suspicious of the building activities in Jerusalem. How then could the same king have commissioned Nehemiah to rebuild the walls of the city in 445? By then both the Egyptian revolt and the rebellion of Megabyzus had been resolved.

Artaxerxes I ended his long forty-year reign by dying from natural causes in the winter of 424 B.C.—a rarity in view of the frequent assassinations of Persian kings.

3. Authorship and Date

As in the closely related books of Chronicles, one notes the prominence of various lists in Ezra-Nehemiah. Evidently obtained from official sources, these comprise (1) the vessels of the temple (Ezr 1:9–11); (2) the returned exiles (Ezr 2:1–70; Ne 7:6–73); (3) the genealogy of Ezra (Ezr 7:1–5); (4) the heads of the clans (Ezr 8:1–14); (5) those involved in mixed marriages (Ezr 10:18–43); (6) those who helped rebuild the wall (Ne 3); (7) those who sealed the covenant (Ne 10:1–27); (8) residents of Jerusalem and other cities (Ne 11:3–36); and (9) priests and Levites (Ne 12:1–26).

Also included in Ezra are seven official documents or letters (all, except the first, in Aramaic; the first is in Hebrew): (1) the decree of Cyrus (Ezr 1:2–4); (2) the accusation of Rehum et al. against the Jews (4:11–16); (3) the reply of Artaxerxes I (4:17–22); (4) the report from Tattenai (5:7–17); (5) the memorandum of Cyrus’s decree (6:2b–5); (6) Darius’s reply to Tattenai (6:6–22); (7) the king’s authorization to Ezra (7:12–26).

Certain characteristics common to both Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah have led many to hold that the author of Chronicles was also the author/compiler of Ezra-Nehemiah. The verses at the end of Chronicles and at the beginning of Ezra are identical (see comment on Ezr 1:1). Both Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah exhibit a fondness for lists, for the description of religious festivals, and for certain phrases. Especially striking in these books is the prominence of the Levites and of temple personnel. Because of his interest in the temple and the cult, it is assumed that the “Chronicler” was a Levite, or even a singer.

Though there are many complex relationships between Ezra-Nehemiah and Chronicles, we regard Nehemiah as the author of the Nehemiah memoirs and Ezra as the author of both the Ezra memoirs and the Ezra narrative, with a later follower of Ezra’s circle as the Chronicler. We would date the composition of the Ezra materials about 440, the Nehemiah memoirs about 430, and 1 and 2 Chronicles about 400.

4. Purpose and Values

Ezra and Nehemiah record the return of the Jewish exiles from Babylonia and the rebuilding of the temple and the walls around Jerusalem. These accounts highlight the importance of the temple and its personnel. Of vital importance were the attempts to keep the community pure from the syncretistic influence of the neighbors who surrounded it. In some cases Jewish communities compromised and were assimilated out of existence, as at Elephantine in Egypt. The measures taken by Ezra and Nehemiah to safeguard the Jews from commingling with non-Jews may appear harsh to modern society, but in the light of history they were necessary.

a. The book of Ezra

The book of Ezra reveals the providential intervention of the God of heaven on behalf of his people. In ch. 1 the Lord is sovereign over all kingdoms (v.2) and moves even the heart of a pagan ruler to fulfill his will (v.1). He accomplishes the refining of his people through calamities like the Conquest and the Exile. He stirs the heart of his people to respond and raises men of God to lead his people (v.11). Ezra 3 shows that the service of God requires a united effort (v.1), leadership (v.2a), obedience to God’s Word (v.2b), courage in the face of opposition (v.3), offerings and funds (vv.4–7), and an organized division of labor (vv.8–9). Meeting these requirements resulted in a sound foundation for later work (v.11), tears and joy (vv.11–12), and praise and thanksgiving to the Lord (v.11).

Ezra 4 teaches that doing the work of God brings opposition: in the guise of proffered cooperation from those who do not share our basic theological convictions (vv.1–2) to complete work that we alone are responsible for (v.3); and from various groups of opponents, such as those who would discourage and intimidate us (v.4), professional counselors who offer misleading advice (v.5), false accusers (vv.6, 13), and secular authorities (vv.7, 21–24). Far from being discouraged, however, we need to be alert and vigorous, knowing that by God’s grace we can triumph over all opposition and accomplish his will with rejoicing (6:14–16).

Ezra experienced the good hand of God. As a scribe he was more than a scholar—he was an expounder of the Scriptures (7:6, 12). He believed that God could guide and protect from misfortune (8:20–22). As an inspired leader he enlisted others and assigned trustworthy men to their tasks (7:27–28; 8:15, 24). He regarded what he did as a sacred trust (8:21–28). Ezra was above all a man of fervent prayer (8:21; 10:1), deep piety, and humility (7:10, 27–28; 9:3; 10:6).

b. The book of Nehemiah

The book of Nehemiah, perhaps more than any other book of the OT, reflects the vibrant personality of its author. (1) Nehemiah was a man of responsibility; he served as the king’s cupbearer (1:11–2:1). (2) Nehemiah was a man of vision. (3) He was a man of prayer (1:5–11; 2:4–5). (4) He was a man of action and cooperation (2:16–18; ch. 3). (5) He was a man of compassion (5:8, 18). (6) He was a man who triumphed over opposition. (7) Finally, Nehemiah was a man with right motivation who sought to please and serve his divine Sovereign.

EXPOSITION

I. The First Return From Exile and the Rebuilding of the Temple (1:1–6:22).

A. The First Return of the Exiles (1:1–11)

1. The edict of Cyrus (1:1–4)

It had been nearly seventy years since the first deportation of the Jews by the Babylonians to Mesopotamia. Though the initial years must have been difficult, the second and third generation of Jews born in the Exile had adjusted to their surroundings. Though some had become so comfortable that they refused to return to Judah when given the opportunity, still others, sustained by the examples and teachings of leaders like Daniel and Ezekiel, retained their faith in the Lord’s promises and their allegiance to their homeland.

1 Ezra l:l–3a is virtually identical with 2Ch 36:22–23. “In the first year” means the first regnal year of Cyrus, beginning in Nisan 538, after his capture of Babylon in October 539. Cyrus, the founder of the Persian Empire, reigned over the Persians from 559 till 530 B.C. He established Persian dominance over the Medes in 550, conquered Lydia and Anatolia in 547–546, and captured Babylon in 539. Isaiah 44:28 and 45:1 speak of Cyrus as the Lord’s “shepherd” and his “anointed.”

Daniel (Da 1:21; 6:28; 10:1) was in Babylon when Cyrus captured it. “The word of the LORD spoken by Jeremiah” was the prophet’s prediction (Jer 25:1–12; 29:10) of a seventy-year Babylonian captivity. The first deportations had begun in 605, in the third year of Jehoiakim (see Da 1:1). The seventieth year would be 536.

“Proclamation” (GK 7754) was an oral announcement in the native language in contrast to the copy of the decree in 6:3–5, which was an Aramaic memorandum for the archives.

2 The phrase “the God of heaven” occurs primarily in the postexilic books (i.e., Ezra, Nehemiah, Daniel). The city of Jerusalem and the house of God are both prominent subjects in Ezra-Nehemiah. “A temple for him at Jerusalem in Judah” is literally “a house for him in Jerusalem that is in Judah.” The formulation “Jerusalem that is in Judah” is characteristic of Persian bureaucratic style. Cyrus instituted the enlightened policy of placating the gods of his subject peoples rather than carrying off their cult statues as the Assyrians, Elamites, Hittites, and Babylonians had done before. His generosity to the Jews was also paralleled by his benevolence to the Babylonians. Ultimately, however, it was the Lord who had “moved” his heart.

3–4 The religious orientation of the Achaemenid kings—Cyrus and his successors—is a controversial issue. “Where survivors may now be living” (lit., “everyone who remains over”) refers to survivors of the capture and deportation (cf. Ne 1:2). The Hebrew word for “living” (GK 1591) is cognate to the word for “resident alien.” The deportees continued to be regarded as aliens, as were the Susians and Elamites who were “resident” in Samaria years after their deportation (4:10, 17). “The people of any place” probably designates the many Jews, especially of the second and the third generation, who did not wish to leave the land of their birth. “Freewill offerings” were voluntary gifts (vv.4, 6; 2:68–69; 3:5; 7:13–16; 8:28) and voluntary service (v.5; 7:13), the keys to the restoration of God’s temple and its service.

2. The Return under Sheshbazzar (1:5–11)

5–6 The Lord stirred not only the heart of the Persian king but also the hearts of many of the exiles who had maintained their faith in the Lord in spite of the devastation of their homeland. A vivid attestation to this faith is an inscription carved at Khirbet Beit Lei, five miles east of Lachish, which can be translated: “I am the Lord your God: I will accept the cities of Judah and will redeem Jerusalem,” perhaps incised by a refugee to express his trust in God’s faithfulness despite the desolation of the Holy City (cf. La 3:22–24).

7 Conquerors customarily carried off the statues of the gods of conquered cities. The Philistines took the ark of the Jews and placed it in the temple of Dagon (1Sa 5:2). The Hittites took the statue of Marduk when they conquered the city of Babylon. As the Jews did not have a statue of the Lord, Nebuchadnezzar carried off the temple goods instead (cf. 2Ki 25:13; Jer 52:17).

Jeremiah spoke of false prophets who prematurely predicted the return of these vessels (Jer 27:16–22; 28:6); he prophesied their ultimate return (27:22). Belshazzar had the audacity to drink from some of the temple vessels (Da 5:23).

8 The Persian name “Mithredath” means “given by Mithra.” Mithra(s) was the Persian god whose mystery religion became popular in the Greco-Roman world. Another official with the same name appears in 4:7. Sheshbazzar, who had a Babylonian name, was probably a Jewish official who served as a deputy governor of Judah under the satrap in Samaria (cf. Ezr 5:14).

9–11 When the Assyrian and Babylonian conquerors carried off booty, their scribes made a careful inventory of it. The actual figures in the Hebrew text add up to 2,499 rather than 5,400, perhaps because only the larger and more valuable vessels were specified. The exact meanings of the Hebrew words for the objects are uncertain. We know nothing about the details of Sheshbazzar’s journey, which probably took place in the spring of 537. Judging from Ezra’s later journey (7:8–9), the trip probably took about four months. The caravan would have proceeded from Babylonia up the Euphrates River and then south through the Orontes Valley of Syria to Palestine.

B. The List of Returning Exiles (2:1–70)

1. Leaders of the return (2:1–2a)

1 The list of returning exiles in vv.1–70 almost exactly parallels the list in Ne 7:6–73. The list of localities indicates that people retained their memories of their homes and that exiles from a very wide background of tribes, villages, and towns returned. A comparison of Ezr 2 with Ne 7 reveals a number of differences in both the names and the numbers that are listed. Though the lists of temple personnel show few variations, there are differences in about half the cases of the lists of the laity. Many differences may be explained by assuming that a cipher notation was used with vertical strokes for units, horizontal strokes for tens, and stylized mems (Heb. letter “m”) for hundreds.

2a The KJV’s colon after Zerubbabel implies that all those who followed were among those returning with Zerubbabel in 537. The NIV, NRSV, et al., place a comma after Zerubbabel, leaving open the possibility that the list may include those who returned to Judah at a later date. The list of eleven leaders in Ezr 2 is increased by the addition of “Nahamani” inserted before the name of Mordecai in Ne 7:7.

On “Zerubbabel” see 5:2. “Jeshua” is a name similar to “Joshua” (Ne 8:17) and to the Greek “Jesus”; it means “The LORD [Yahweh] is salvation.” If he is the same as the Joshua of Hag 1:1, he was the son of Jehozadak, the high priest carried into exile (1Ch 6:15) and the grandson of Seraiah, the high priest put to death by Nebuchadnezzar (2Ki 25:18–21). “Nehemiah” was not the same person as the king’s cupbearer. “Seraiah” means “The LORD is Prince.” “Reelaiah” is paralleled in Ne 7:7 by “Raamiah.” “Mordecai” is based on the name of the god of Babylon, Marduk (Jer 50:2). It is the name borne by Esther’s uncle. “Mispar” is paralleled in Ne 7:7 by “Mispereth.” “Bigvai” is a Persian name meaning “happy.”

2. Families (2:2b–20)

2b “The list of the men of the people of Israel” may have been of males only over the age of twelve.

3 “The descendants of Parosh” represented the largest family of priests returning from Babylon. Members of this family returned with Ezra (8:3); some of them assisted in rebuilding the wall (Ne 3:25). “Parosh” (GK 7283) means “flea” (cf. GK 7282) and may connote insignificance (cf. 1Sa 24:14). Insect and animal names were common among the Hebrews.

4–12 “Shephatiah” means “The LORD has judged.” Other members of the family returned with Ezra (8:8). “Arah” means “wild ox.” “Pahath-Moab” means “governor of Moab” (cf. 8:4; 10:30; Ne 7:11; 10:14). These may be the descendants of the tribe of Reuben who were deported from the province of Moab by Tiglath-pileser III (cf. 1Ch 5:3–8). “Elam” was the name of the country in southwestern Iran in the area of Susa (cf. v.31; 8:7; 10:2, 26; Ne 7:12; 10:14).

“Zaccai” may mean “pure” or may be a shortened form of Zechariah (“The LORD has remembered”). “Bani” is a shortened form of Benaiah (“The LORD has built”); Ne 7:15 has Binnui. “Azgad” (“Gad is strong”) is either a reference to Gad, the god of fortune, or to the Transjordanian tribe of Gad. The greatest numerical discrepancy occurs here: Ezra lists 1,222 whereas Nehemiah lists 2,322.

13–20 “Adonikam” means “my Lord has arisen.” “Ater” means “Lefty” (cf. Jdg 3:15; 20:16). “Hezekiah” means “The LORD is my strength.” “Bezai,” a shorted form of Bezaleel, means “in the shadow of God.”

Copyright ©1991 Zondervan Publishing House.

3. Villagers (2:21–35)

Verses 21–35 list a series of villages and towns, most of them in Benjamite territory north of Jerusalem. Significantly, no references are to towns in the Negev south of Judah. When Nebuchadnezzar overran Judah (Jer 13:19), the Edomites (cf. Obadiah) opportunistically occupied the area. By the fifth century B.C., Nabataean Arabs (Mal 1:2–5) were pressing on the Edomites, who moved west and occupied the area south of Hebron, later known as Idumaea.

21–25 “Bethlehem”—among the returnees may have been the ancestors of Jesus (Mic 5:2). “Netophah,” a city south of Jerusalem, was settled by Levites (1Ch 9:16). “Anathoth,” a village named after the Canaanite goddess Anath, was located three miles north of Jerusalem and was the home of the prophet Jeremiah (Jer 1:1). “Azmaveth” was two miles farther north. “Kiriath Jearim” means “village of the woods,” (cf. Ne 7:29). This was the site eight miles northwest of Jerusalem where the ark rested (1Sa 6:21; 7:1). “Beeroth” means “wells,” a site located twelve miles north of Jerusalem.

26–28 “Ramah” (“the height”) was five miles north of Jerusalem. “Geba” was located east of Ramah. “Micmash,” eight miles northeast of Jerusalem, was the scene of Jonathan’s exploit (1Sa 13:23). “Bethel” (“the house of God”) was located twelve miles north of Jerusalem. As a border town, it probably became a part of Judah in Josiah’s reign. Bethel, however, was destroyed in the transition between the Babylonian and Persian periods. Excavations have revealed a small town on the site in Ezra’s day.

29–35 “Nebo” was perhaps the same as Nob, which has been located on Mount Scopus, just to the east of Jerusalem. “Harim” means “dedicated to God.” “Lod,” modern Lydda, ten miles southeast of Jaffa, is today the site of the Israeli International Airport. “Jericho” is the famous oasis city just north of the Dead Sea. “Senaah” means “the hated one.” The largest number of returnees (3, 630) is associated with Senaah, which is perhaps not a specific locality or family but a low-caste people.

4. Priests (2:36–39)

Four clans of priests are named with a total of 4,289, or about one-tenth the total. They may have been inspired by the hope of serving in a rebuilt temple.

36–39 “Jedaiah” (“The LORD has known”) was a family of priests noted during the time of David (1Ch 24:7). “Immer” means “lamb” (cf. 1Ch 24:14). On “Harim” see comment on v.32

5. Levites and temple personnel (2:40–42)

40 The Levites, descendants of Levi (Ge 29:34), may have originally been regarded as priests (Dt 18:6–8); but they became subordinate to the priestly descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses (Nu 3:9–10; 1Ch 16:4–42; 23:26–32). The Levites were then prohibited from offering sacrifices on the altar (Nu 16:40; 18:7). As the Levites had no inheritance in land, they lived in forty-eight Levitical cities and were supported by tithes (Dt 12:12, 18; 14:29). They were butchers, doorkeepers, singers (1Ch 15:22; 16:4–7), scribes and teachers (2Ch 35:3; Ne 8:7, 9), and even temple beggars (2Ch 24:5–11).

41 On “the singers,” see Ne 11:22–23; 12:29; 13:10. “Asaph” (lit., “he removed”) was one of the three Levites appointed by David over the temple singers.

42 “Gatekeepers” (GK 8788) are mentioned thirteen times in Ezra-Nehemiah, nineteen times in Chronicles. They are usually regarded as Levites (1Ch 9:26; 2Ch 8:14; 23:4; Ne 12:25; 13:22) but are sometimes differentiated from them (2Ch 35:15). At times as many as four thousand gatekeepers were mentioned (1Ch 23:5). Their primary function was to tend the doors and gates of the temple (1Sa 3:15; 1Ch 9:17–32), though they were also expected to perform other menial tasks (2Ch 31:14). The psalmist said he would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of his God than to dwell in the tents of the wicked (Ps 84:10). The 139 gatekeepers listed here belonged to six small clans. “Shallum” means “complete”; “Talmon” means “brightness”; “Akkub” means “protected.”

6. Temple servants (2:43–58)

43–45 A long list of names (thirty-five in Ezra, thirty-two in Nehemiah) follows the heading “temple servants”; but the clans must have been very small, averaging about nine members. The temple servants and the sons of Solomon’s servants together numbered 392 (v.58)—more than the total of the Levites, gatekeepers, and singers (vv.40–42). Though of a very menial status, they must have served God with true devotion. The Hebrew word for “temple servants” (“Nethinim”; GK 5987) occurs only in 1Ch 9:2 and in Ezra-Nehemiah. They occupied a special quarter in Jerusalem (Ne 3:26, 31; 11:21) and enjoyed exemption from taxes (Ezr 7:24). They participated in the rebuilding of the wall (Ne 3:26) and signed Nehemiah’s covenant (Ne 10:29).

46–54 “Hanan” (“[God] is gracious”) is derived from the verb for “to be gracious.” The name “Johanan” (“The LORD is gracious”) has given us the name John. “Giddel,” a shortened form of Geddeliah, means “The LORD has made great.” “Rezin” is an Aramaic name that means “prince” (cf. Pr 14:28). “Meunim” seems to be related to the Maonites (Jdg 10:12), an Arab tribe south of the Dead Sea subdued by Uzziah (2Ch 26:7). A city near Petra is named Maan. “Nephussim” refers to a Bedouin tribe descended from Ishmael (Ge 25:15; 1Ch 1:31; 5:18–22). “Neziah” is “faithful”; “Hatipha” means “snatched,” as a captive in childhood.

55–58 The phrase “the descendants of the servants of Solomon” occurs only in this passage and in Ne 7:60; 11:3. These may be the descendants of the Canaanites whom Solomon enslaved (1Ki 9:20–21). “Hassophereth” is a feminine form that means “the scribe”; women scribes were rare. An analysis of the figures in these lists yields the following percentages of the total (v.64): families, 53.2; villagers, 29.6; priests, 14.7; Levites, 0.2; singers, 0.4; gatekeepers, 0.5; temple servants and descendants of the servants of Solomon, 1.4.

7. Individuals lacking evidence of their genealogies (2:59–63)

59 The Hebrew word tel (GK 9424) designates hilllike mounds that cover the remains of ruined cities. “Tel Melah” (“mound of salt”) is possibly a mound strewed with salt (cf. Jdg 9:45). “Tel Harsha” is “mound of potsherds.” Tel-Abib (Eze 3:15) means the “mound of a flood,” i.e., a place destroyed by a flood.

The Jewish exiles were settled along the Kebar River (Eze 1:1) near the city of Nippur, a city in southern Mesopotamia that was the stronghold of rebels. Of the exiles who returned, members of three lay families and three priestly families were unable at this time to prove their descent. Some may have derived from proselytes; others may have temporarily lost access to their genealogical records.

60 “Delaiah” is “The LORD has drawn.” “Tobiah” (“The LORD is good”) was the name also of one of Nehemiah’s chief adversaries (Ne 2:10, 19). The total of 652 could not prove their genealogies.

61 “Hobaiah” means “The LORD has hidden.” “Barzillai” (“man of iron”) of Gilead in Transjordan helped David during his flight from his son Absalom (2Sa 17:27–29; 19:31–39; 1Ki 2:7). That the bridegroom took the name of his wife’s father reflects a marriage arranged by a father who had only daughters. The children from this marriage belonged to the wife’s family (cf. Ge 29–31; 1Ch 2:34–36).

62 Genealogies figure prominently in Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah. The knowledge of relationships was highly regarded in ancient times.

63 “The governor” probably refers here to either Sheshbazzar or Zerubbabel. “The most sacred food” refers to the most holy part of the offering—the portion of the priests. “The Urim and Thummim,” objects kept in the breastplate of the high priest, were used for divining God’s will (cf. Ex 28:30; Lev 8:8; Nu 27:21; Dt 33:8). They were probably two small objects made of wood, bone, or stone, perhaps of different colors or with different inscriptions, that would give a yes or no answer.

8. Totals (2:64–67)

64 The given total of 42,360 is considerably more than the sum of the actual figures given from the figures in Ezr 2 and Ne 7. To account for the difference of about twelve thousand presents problems. Were these unspecified people women and/or children? If there were relatively few women among the returnees, the pressures for intermarriage would have been considerable.

65 The ratio of slaves—one to six—is relatively high; that so many would return with their masters speaks highly of the relatively benevolent treatment of slaves by the Jews. The male and female singers listed here may have been secular singers who sang at weddings, funerals, etc. (2Ch 35:25) as distinct from the male temple singers of v.41.

66 “Horses” in the OT are usually associated with royalty and the military. The horses listed here may have been a donation from Cyrus for the nobility. “Mules” are hybrid offspring of donkey stallions and mares. They combine the strength and size of the horse with the patience and sure-footedness of the donkey. They were not originally bred in Palestine; Solomon had to import them (1Ki 10:25; 2Ch 9:24). As precious animals they were used by the royalty and wealthy (1Ki 1:33; Isa 66:20).

67 The “camels” mentioned in the OT were the one-humped Arabian camels as distinct from the two-humped Bactrian camels. The camel can carry its rider and about four hundred pounds and can travel three or four days without drinking. “Donkeys” were surefooted and able to live on poor forage. They were used to carry loads, women, or children. Sheep, goats, and cattle are not mentioned. They would have slowed the caravan.

9. Offerings (2:68–69)

68 The caravan probably followed the Euphrates River north to a point east of Aleppo, crossed west to the Orontes River Valley, then traveled south to Hamath, Homs, and Riblah. They would then have either passed through the Beqah Valley in Lebanon (cf. Jer 39:5–7; 52:9–10, 26–27) or have proceeded east of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains to Damascus and then to Palestine. As the people were expending most of their savings, their giving demonstrated a true spirit of dedication to God’s service (cf. Ex 36:5–7; 2Co 9:6–7).

69 The parallel passage in Ne 7:70–72 gives a fuller description than the account in Ezra. In Ezra the gifts come from the heads of the clans but in Nehemiah from three sources: the governor, the chiefs of the clans, and the rest of the people.

The “drachma” (GK 2007) was the Greek silver coin worth a day’s wage in the late fifth century B.C. More likely the coin intended here was the Persian daric, which was a gold coin, named probably after Darius I, who began minting it. The coin was famed for its purity, which was guaranteed by the king. Its value equaled the price of an ox or a month’s wages for a soldier. Since the coin was not in use until the time of Darius I (522–486 B.C.), its occurrence here in 537 B.C. has been labeled anachronistic. Its use is better viewed as a modernization by terms current at the time of the book’s composition of earlier values, perhaps the Median shekel.

A “mina” equaled 1.26 pounds of silver; five thousand minas would be 6,300 pounds of silver. A mina equals five years’ wages.

10. Settlement of the exiles (2:70)

70 Later Nehemiah would be compelled to move people by lot to reinforce the population of Jerusalem, as the capital city had suffered the severest loss of life at the time of the Babylonian attacks. The survivors, who came for the most part from towns in the countryside, naturally preferred to resettle in their hometowns.

C. The Revival of Temple Worship (3:1–13)

1. The rebuilding of the altar (3:1–3)

1 “The seventh month” is Tishri (Sept-Oct), about three months after the arrival of the exiles in Palestine. Tishri is one of the most sacred months of the Jewish year. The first day is the New Year’s Day (Rosh Hashanah) of the civil calendar, proclaimed with the blowing of trumpets and a holy convocation (Lev 23:24). Ten days later the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) is observed (Lev 23:27). From the fifteenth to the twenty-second day, the Feast of Tabernacles (Succoth) is celebrated (Lev 23:34–36). “Assembled as one man” and similar expressions of the unity of Israel are found in Nu 14:15; Jdg 6:16; 20:1, 8, 11; 1Sa 11:7; 2Sa 19:14.

2 Jeshua, the high priest, took precedence over Zerubbabel, the civil leader, in view of the nature of the occasions (cf. v.8; 5:2; Hag 1:1). During their long stay in Babylon, the Jews were not able to offer any sacrifices, as this could only be done in Jerusalem. Instead they were surrounded by a myriad of pagan temples. Thus the exiles’ first task in the midst of hostile neighbors was to erect once more an altar to sacrifice to the Lord.

The Jews’ “enemies” did not have anything to fear from the rebuilding of the temple, as they did later from the rebuilding of the wall. Sincerely or not, they at first offered their help to rebuild the temple.

3 “Despite their fear” is literally “for with fear” or “for in fear.” The Hebrew word means a terror inspired by people (Pr 20:2) or by animals (Job 39:20). “The peoples around them” is literally “peoples of the lands.”

2. The Festival of Booths (3:4–6)

4 The original Hebrew word for “tabernacle” (GK 6109) refers to the “huts” constructed for this feast, which is sometimes simply called “the feast” or “the feast of the Lord.” It was originally a joyous harvest celebration (Ex 23:14–16; 34:22–23; Lev 23:33–43; Nu 29:12–40; Dt 16:13–16; cf. 1Sa 1:1–3; 1Ki 12:32).

Jews today celebrate the feast by building a hut covered with an open roof of branches, decorated with fruits and vegetables. Following Lev 23:40, Jews also use the palm, the willow, and the myrtle as the “lulav” (“a shoot or young branch”) and the “ethrog” (a yellow citron known in Israel only from Hellenistic times). During each of the nine days of the feast, the lulav and the ethrog are held in the hands and waved in all directions. The “burnt offerings” (GK 6592) were those sacrifices prescribed for morning (Lev 1:13) and evening (Nu 28:3–4).

5–6 The new moon marked the first day of the month and was a holy day (Nu 28:11–15; cf. Col 2:16). “The appointed sacred feasts” include such festivals as the Passover, Weeks (Pentecost), and the Day of Atonement (Lev 23). The renewal of the “freewill offerings” (cf. 1:4; GK 5607) fulfilled the promise of Jer 33:10–11. Notice that the revival of the services preceded the erection of the temple itself.

3. The beginning of temple reconstruction (3:7–13)

7 As with the first temple, the Phoenicians (of Tyre and Sidon) cooperated by sending timbers and workmen (1Ki 5:7–12). The latter were paid in “money” (lit., “silver”) that would have been weighed out in shekels (see comment on 2:69). Ancient Phoenicia (modern Lebanon) was renowned for its cedars and other coniferous trees. Both the Mesopotamians and the Egyptians sought to obtain its timbers either by trade or by conquest. Cedars, mentioned seventy-one times in the OT, can grow to a height of 120 feet with a girth of 30 to 40 feet. Their fragrant wood resists rot and insects. The wood was floated on rafts down the coast and unloaded at Joppa (cf. 1Ki 5:9; 2Ch 2:15–16).

Sidon, twenty-eight miles south of modern Beirut, was one of the greatest of all the Phoenician cities (Ge 10:19; 1Ki 5:6; 16:31; 1Ch 22:4). After the conquest of the island of Tyre by Nebuchadnezzar following a thirteen-year siege, Sidon became prominent. Renowned for its maritime trade (Eze 26:4–14), Tyre was later transformed into a peninsula by Alexander the Great.

8–9 The second month, Iyyar (Apr/May), was the same month when Solomon began his temple (1Ki 6:1). As the Jews probably returned to Palestine in the spring of 537, the second year would be the spring of 536. Previously the age limit for the Levites was thirty (Nu 4:3) or twenty-five years (Nu 8:24). It was reduced to twenty (1Ch 23:24, 27; 2Ch 31:17), no doubt because of the scarcity of Levites. Zerubbabel and Jeshua were involved in laying the foundation of the second temple, though 5:16 describes Sheshbazzar as also laying the foundation.

10 The “trumpets” (GK 2956) were made of beaten silver (Nu 10:2). Except perhaps for their use at the coronation of Joash (2Ki 11:14; 2Ch 23:13), trumpets were always blown by priests (Nu 10:8; 1Ch 15:24; 16:6). They were most often used on joyous occasions such as here and at the dedication of the rebuilt walls of Jerusalem (Ne 12:35; cf. 2Ch 5:13; Ps 98:6). “Cymbals” (GK 5199) were also played by priests and Levites.

11 “They sang” may be antiphonal singing by a choir divided into two groups, i.e., singing responsively (see Ne 12:8–9). “He is good,” a constant refrain in Scriptures (1Ch 16:34; 2Ch 7:3; Pss 106:1; 136:1; Jer 33:10–11), implies the goodness of a covenant-keeping God. “Love” (GK 2876) means “steadfast love.”

12–13 The loud shouting expressed the great jubilation of the people (cf. 10:12; cf. Jos 6:5, 20; 1Sa 4:5; Ps 95:1–2). The tears and outcries expressed the deep emotion of the occasion. Traditionally, Hebrews show their emotions by weeping out loud (cf. 10:1; Ne 1:4; 8:9). Whereas the elders were overcome with the memories of the splendors of Solomon’s temple, the younger returnees shouted with great excitement at the prospect of a new temple. The God who had permitted judgment was also the God who had brought them back and would enable them to complete this project.

D. The Opposition to the Rebuilding (4:1–24).

1. Opposition during the reign of Cyrus (4:1–5)

This chapter summarizes various attempts to thwart the efforts of the Jews. In vv.1–5 the author describes events under Cyrus (539–530 B.C.), in v.6 under Xerxes (485–465), in vv.7–23 under Artaxerxes I (464–424). He then reverts in v.24 to the time of Darius I (522–486), when the temple was completed (cf. Hag 1–2). The author drew on Aramaic documents from v.8 to 6:18, with a further Aramaic section in 7:12–26.

1–2 As most of the exiles were from Judah, their descendants became known as Jews. Benjamin, the small tribe occupying the area immediately north of Judah, was the only tribe beside Judah that remained loyal to Rehoboam when the ten northern tribes rebelled. Saul, the first king of Israel, came from this tribe, as did Saul of Tarsus (Php 3:5).

The people who proffered their help were evidently from the area of Samaria, though they are not explicitly described as such. After the fall of Samaria in 722 B.C., the Assyrian kings kept importing inhabitants from Mesopotamia and Syria “who worshiped the LORD, but . . . also served their own gods” (2Ki 17:24–33). The newcomers’ influence doubtless diluted further the faith of the northerners, who had already apostasized from the sole worship of the Lord in the tenth century.

Even after the destruction of the temple, worshipers from Shiloh and Shechem in the north came to offer cereals and incense at the site of the ruined temple (Jer 41:5). Moreover, the northerners did not abandon faith in the Lord, as we see from the names given to Sanballat’s sons, Delaiah and Shelemaiah (the “iah” refers to “Yah” or “Yahweh”). However, they retained Israel’s Lord, not as the sole God, but as one god among many gods; Sanballat’s name honors the moon god Sin.

3 The Jews tried tactfully to reject the aid proffered by the northerners by referring to the provisions of the king’s decree. Nonetheless their response understandably aroused hostility and determined opposition.

4 “The peoples around them” (lit., “the people of the land”) began “to discourage” (lit., “to weaken the hands of”; cf. Jer 38:4) the Jews. “Make them afraid” (GK 987) often describes the fear aroused in a battle situation (Jdg 20:41; 2Sa 4:1; 2Ch 32:18; Da 11:44; Zec 8:10).

5 On the hiring of counselors, compare the hiring of Balaam (Dt 23:4–5) and the hiring of the prophets to intimidate Nehemiah (Ne 13:2). “Down to the reign of Darius king of Persia” passes over the intervening reign of Cambyses (529–522), who conquered Egypt in 525 B.C., and that of the usurper, the Pseudo-Smerdis, who seized power in 522 for seven months.

2. Opposition during the reign of Xerxes (4:6)

6 “Xerxes” (Heb. “Ahasuerus”; cf. NIV note; the king mentioned in Esther) was the son of Darius. When Darius died at the end of 486, Egypt rebelled; and Xerxes had to march west to suppress the revolt. The Persians finally regained control by the end of 483. “Accusation” (lit., “hostility”; GK 8478) occurs only here and in Ge 26:21, where it is the name of a well the herdsmen of Isaac and Gerar quarreled over.

3. Opposition during the reign of Artaxerxes I (4:7–23)

a. The letter to the king (4:7–16)

7 There were three Persian kings named “Artaxerxes”: Artaxerxes I (464–424), Artaxerxes II (403–359), and Artaxerxes III (358–337). The king in this passage is Artaxerxes I. The author of the letter was Tabeel, writing with the approval of Mithredath (on “Mithredath,” see comment on 1:8). “Tabeel” means “God is good” (cf Isa 7:6). Near-Eastern kings used an elaborate system of informers and spies. But God’s people could take assurance in their conviction that God’s intelligence system is not only more efficient than any king’s espionage network but is omniscient (cf. 2Ch 16:9; Zec 4:10).

8 “Rehum” (“merciful”) was an official with the role of a “chancellor” or a “commissioner.” “Shimshai” means “my sun” (cf. Samson). Rehum dictated and Shimshai wrote the letter in Aramaic. It would then have been read in a Persian translation before the king (v.18).

9 “Associates” (GK 10360) were persons supported by the same fief, often children of the same parents. Persian bureaucracy reflected prominently the principle of collegiality; each responsibility was shared among colleagues. “Erech” was a great city (Ge 10:10) of the Sumerians, famed as the home of the legendary Gilgamesh. Excavations at the site have produced the earliest examples of writing. Susa was the major city of Elam in southwest Iran. Because of Susa’s part in a major revolt against the last great Assyrian king (669–633 B.C.), Ashurbanipal, the city was brutally destroyed in 640. So thorough was the Assyrian destruction of Susa’s ziggurat that only recently have excavators recognized its location.

10–11 Ashurbanipal was famed for his large library at Nineveh. He is not named elsewhere in the Bible but was probably the king who freed Manasseh from exile (2Ch 33:11–13). He may be the unnamed Assyrian king who deported people to Samaria according to 2Ki 17:24. The descendants of such deportees, removed from their homelands nearly two centuries before, still commonly stressed their origins. Probably the murder of the Israelite king Amon (640–642 B.C.) was the result of an anti-Assyrian movement inspired by the revolt in Elam and Babylonia. The Assyrians may then have deported the rebellious Samaritans and replaced them with the rebellious Elamites and Babylonians.

11 “Trans-Euphrates” (lit., “across the river”) is a phrase that first appeared in the reign of Esarhaddon. Palestinians defined the “land across the River” as Mesopotamia (Jos 24:2–3, 14–15; 2Sa 10:16). Mesopotamians, on the other hand, saw it as including Syria, Phoenicia, and Palestine (1Ki 4:24). When Cyrus conquered Babylon in 539, he appointed Gubaru governor of Babylon and the “land beyond the River.” This became the official title of the Fifth Satrapy (5:3; 6:6; Ne 2:7; et al.).

12–13 The Aramaic word for “repairing” (GK 10253) is from either the root “to repair” or the root “to lay.” “Taxes” (GK 10402) designates a fixed annual tax paid by the provinces into the imperial treasuries. “Tribute” (GK 10107) was the rent tax in Babylonia. Estimates are that between twenty to thirty-five million dollars worth of taxes were collected annually by the Persian king. The Fifth Satrapy, which included Palestine, had to pay the smallest amount of the western satrapies. The Persians took much of the gold and silver coins and melted them down to be stored as bullion. Very little of the taxes returned to benefit the provinces.

14 “We are under obligation to the palace” is literally “we eat the salt of the palace.” Salt was used in the ratification of covenants (Lev 2:13; Nu 18:19; 2Ch 13:5). The English word “salary” is derived from the Latin ration of salt given to soldiers (cf. the expression “a man who is not worth his salt”).

15–16 “The archives” is literally “book of the records” (cf. 6:1–2; Est 2:23; 6:1). There were evidently several repositories of such documents at the major capitals.

b. The letter from the king (4:17–23)

17–20 “Greetings” is the Aramaic shelam (GK 10720; cf. Heb. shalom; GK 8934). As the king was probably illiterate, documents would be read to him (cf. Est 6:1); those written in Aramaic were “translated” into Persian (cf. comments on 4:8; Ne 8:8). There was some truth in the accusation mentioned here. Jerusalem had rebelled against the Assyrians and the Babylonians in 701, 597, and 587 B.C. (2Ki 18:7, 13; 24:1; etc.). According to the Hebrew text of 1Ki 9:18, Solomon rebuilt Tadmor, the important oasis in the Syrian desert that controlled much of the Trans-Euphrates area. His international prestige is reflected in that he was given a pharaoh’s daughter in marriage (1Ki 3:1; 7:8).

21–23 After provincial authorities had intervened, the Persian king ordered a halt to the Jewish attempt to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem (see comment on Ne 1:3). Most scholars date the episode of vv.7–23 before 445 B.C. The forcible destruction of these recently rebuilt walls rather than the destruction by Nebuchadnezzar then becomes the basis of the report made to Nehemiah.

4. Resumption of work under Darius (4:24)

24 The writer, after a long digression detailing opposition to Jewish efforts, returns to his original subject—rebuilding the temple (vv.1–3). According to Persian reckoning the second regnal year of Darius I began on 1 Nisan (Apr 3), 520 B.C., and lasted till Feb 21, 519. In that year the prophet Haggai (Hag 1:1–5) exhorted Zerubbabel to begin rebuilding the temple on the first day of the sixth month (Aug 29). Work began on the temple on the twenty-fourth day of the month—Sept 21 (Hag 1:15). The date is significant. During his first two years, Darius fought numerous battles against nine rebels, as recounted in his famous Behistun Inscription. Only after the stabilization of the Persian Empire could efforts to rebuild the temple be permitted.

E. The Completion of the Temple (5:1–6:22)

1. A new beginning inspired by Haggai and Zechariah (5:1–2)

1 Beginning on Aug 29, 520 B.C. (Hag 1:1) and continuing till Dec 8 (Hag 2:1–9, 20–23), the prophet Haggai delivered a series of messages to stir the people to commence work on the temple. Two months after Haggai’s first speech, Zechariah joined him (Zec 1:1). Haggai 1:6 describes the deplorable situation: housing shortages, disappointing harvests, lack of clothing and jobs, and inadequate funds—perhaps as a result of inflation (see on comments Ne 5). Haggai rebuked the people and proclaimed that because the Lord’s house had remained “a ruin” (Hag 1:4, 9), the Lord would bring a drought (Hag 1:11) on the land. This implies that very little progress had been made in the sixteen years since the first foundation was laid.

2 “Zerubbabel” is a Babylonian name that means “seed of Babylon”; it refers to the man’s birth in exile, probably before 570 B.C. Here and in Ezr 3:2, Ne 12:1, and Hag 1:1, he is described as the son of Shealtiel—son of Jehoiachin, penultimate king of Judah (1Ch 3:17). Though Jehoiachin was replaced by Zedekiah, he was regarded as the last legitimate king of Judah. Zerubbabel was the last of the Davidic line to be entrusted with political authority by the occupying powers. In 1Ch 3:19, however, Zerubbabel is listed as a son of Pedaiah, another son of Jehoiachin and brother of Shealtiel. Pedaiah may have married the widow of his dead brother, Shealtiel, in a levirate marriage (Dt 25:5–6). On Jeshua and Jozadak, see comment on 2:2.

2. The intervention of the governor Tattenai (5:3–5)

3–5 A document that can be dated to June 5,502 B.C., cites Ta-at-tan-ni as the “governor” who was subordinate to the satrap over Ebirnari. Shethar-Bozenai may have functioned as a Persian official known as the “inquisitor” or “investigator.” “Structure” (GK 10082) suggests an advanced stage in the rebuilding of the temple. The Persian governor gave the Jews the benefit of the doubt by not stopping the work while the inquiry was proceeding. On the “elders” see v.9; 6:7–8, 14; Jer 29:1; Eze 8:1; 14:1.

3. The report to Darius (5:6–17)

6–7 That such inquiries were sent directly to the king has been vividly confirmed by the Elamite texts from Persepolis, where in 1933–34 several thousand tablets and fragments were found in the fortification wall. Dating from the thirteenth to the twenty-eighth year of Darius (509–494 B.C.), they deal with the transfer and payment of food products. In 1936–38 additional Elamite texts were discovered, dating from the thirtieth year of Darius to the seventh year of Artaxerxes I (492–458 B.C.).

8 The interpretation of the phrase “large stones” is uncertain. The LX X has “choice” or “splendid” stones (cf. 1Ki 7:9–11). The translation “large” (lit., “rolling”; GK 10146) is suggested because the size of the stones was such that they were likely placed on rollers to move them. “Placing the timbers in the walls” may refer to interior wainscoting (1Ki 6:15–18) or to logs alternating with the brick or stone layers in the walls (1Ki 6:36).

9–12 According to 1Ki 6:1, Solomon began building the temple in the fourth year of his reign, in 966 B.C. The project lasted seven years (1Ki 6:38). In response to the challenge of the Persian authorities, the Jewish elders declared that they were the servants of the God of heaven and earth and recounted the building of the first temple by Solomon, which must have been an object of national pride. They then confessed that because of their fathers’ sins, God had been provoked into using the pagan Babylonians in chastising them, just as Jeremiah had warned.

The Chaldeans inhabited the southern regions of Mesopotamia and established the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 B.C.). Their origins are obscure. There may have been some original kinship with the Arameans, though they were consistently distinguished from the Arameans in Assyrian documents (cf. 2Ki 24:2; Jer 35:11). In the late seventh century B.C., the Chaldeans with the Medes, led by Nabopolassar, the father of Nebuchadnezzar, overthrew the Assyrians. Of the fall of Jerusalem on March 16, 597, extant Chaldean chronicles laconically report: “He then captured its king [Jehoiachin] and appointed a king of his own choice [Zedekiah]” (cf. 2Ki 24:17).

13 For the title “king of Babylon,” see comment on Ne 13:6. In cuneiform contracts in Mesopotamia and in Syria, Darius is also designated “king of Babylon.”

14–15 Cyrus appointed Sheshbazzar “governor” (cf. 1:8, 11). Both Sheshbazzar and Zerubbabel (Hag 1:1; 2:2) were “governors.” Both are said to have laid the foundation of the temple (v.16; 1:3; 3:2–8; Hag 1:1, 14–15; 2:2–4, 18). Probably Sheshbazzar was an elderly man about fifty-five to sixty at the time of the return, whereas Zerubbabel was a younger contemporary about forty. Sheshbazzar may have been viewed as the official Persian “governor” whereas Zerubbabel served as the popular leader (3:8–11). This may be why the Jews mentioned Sheshbazzar here when speaking to the Persian authorities. Whereas the high priest Joshua is associated with Zerubbabel, no priest is associated with Sheshbazzar.

With God all things are possible. Consider the fate of the temple and its vessels. How desperate and hopeless the situation of the Jews must have seemed from the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar to the desecration of the temple vessels by Belshazzar in a feast the night Babylon fell to Cyrus (Da 5)! Prior to that night there was utter destruction, deportation, and desecration; after that night reconsecration, return, and rebuilding. For those who could lift their hearts above the dismal prospects of earth to the God of heaven, a promise of an anointed one by the name of Cyrus had been made (Isa 44:28–45:1) long before the capture of Babylon by the Persians. What mere human prognosticator could have guessed such a turn of events?

16–17 It was important that the temple be built on its original “site” (v.15). Though Sheshbazzar presided over the laying of its foundation in 536, so little actually was accomplished that Zerubbabel evidently had to preside over a second foundation some sixteen years later (cf. 6:3). The fate of Sheshbazzar is uncertain. In view of his advanced age, possibly he died soon after his return to Jerusalem.

4. The search for the decree of Cyrus (6:1–5)

1 “The archives” is literally “house of books.” The phrase then reads “in the house of the books where the treasures were laid up.” Many Elamite documents were found in the so-called treasury area of Persepolis, along with other artifacts.

2 Persian officials wrote on scrolls of papyrus and leather, as discoveries in Egypt show. “Citadel” is probably from the Akkadian word for “fortress.” Media was the homeland of the Medes in northwestern Iran. After the rise of Cyrus in 550 B.C., this IndoEuropean tribe became subordinate to the Persians. “Ecbatana” was the capital of Media.

The Aramaic “memorandum” of the decree of Cyrus in vv.3–5 is comparable to the Hebrew version of the king’s proclamation in 1:2–4. In contrast with the latter, the Aramaic is written in a more sober, administrative style without reference to the Lord.

3–5 “Ninety feet high and ninety feet wide” is literally “60 cubits its height and 60 cubits its width” (see NIV note). The cubit was the distance from the elbow to the finger tip, or slightly less than eighteen inches. No length is given here. These dimensions contrast with those of Solomon’s temple, which was 20 cubits wide by 30 cubits high by 60 cubits long (1Ki 6:2). The dimensions here in v.3 are probably not descriptions of the temple as built, but specifications of the outer limits of a building the Persians would support. The second temple was manifestly not as grandiose as the first (3:12; Hag 2:3). On “large stones,” see comment on 5:8 (cf. also 1Ki 6:36; 7:12). Such use of timber beams with masonry is attested at Ras Shamra and elsewhere. On the vessels of the temple, see comment on 5:14–15.

5. Darius’s order for the rebuilding of the temple (6:6–12)

6–7 “Stay away from there” is literally “be distant from there.” When Babylonian kings like Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus rebuilt temples, they searched carefully to discover the exact outlines of the former buildings.

8 “Treasury” (lit., “possessions,” “properties”; GK 10479) occurs frequently in extrabiblical Aramaic with a wide variety of meanings. Here it seems to mean royal “funds,” which could mean that the rebuilding was to be done at government expense, with a hint of government subsidies for the offerings. Ancient documents indicate that the Persians paid for temple repairs out of royal funds.

9 A lamb was offered every morning and evening; two were offered on the Sabbath, seven each at great feasts and at the beginning of each month, and fourteen every day during the Feast of Tabernacles (Lev 1:3, 10; Nu 28). The “burnt offering” (GK 10545) was a sacrifice that was wholly consumed on the altar (in contrast to the fellowship offering; cf. Lev 3; 7:11–36). “Wheat” was offered as fine flour, either alone (Lev 5:11–13), mixed as dough (Lev 2:1–3), or as cakes (Lev 2:4). “Salt” was offered with all oblations (Lev 2:13; Mk 9:49). “Wine” was poured out as a libation (Ex 29:40–41; Lev 23:13, 18, 37). “Oil” was used in the meal offerings. Other ancient documents demonstrate that Persian monarchs were interested in foreign cults.

10 “Sacrifices pleasing” is literally “sacrifices of sweet smell” (cf. Ge 8:21; Da 2:46). In pagan religions the sacrifices were viewed literally as nourishment for the gods, but not in the worship of the Lord (Eze 44:7). Darius also commanded that the Jews be allowed to “pray for the well-being of the king and his sons.”

11 Decrees and treaties customarily had appended a long list of curses against anyone who might disregard them. Anyone who would change Darius’s decree would be “impaled” on a beam from his own house. The OT cites the hanging or fastening of criminals (Ge 40:22; 41:13; Nu 25:4; cf. Est 2:23; 5:14; 9:14; et al.). According to Dt 21:22–23, a criminal was stoned and his corpse hung on a “tree” (cf. 2Sa 21:6, 9).

12 At the end of his famous Behistun Inscription, Darius warned: “If thou shalt behold this inscription or these sculptures, (and) shalt destroy them and shalt not protect them as long as unto thee there is strength, may Ahuramazda be a smiter unto thee, and may family not be unto thee, and what thou shalt do, that for thee may Ahuramazda utterly destroy!”

6. The completion of the temple (6:13–15)

13–14 Work on the temple made little progress because of opposition and the preoccupation of the returnees with their own homes (Hag 1:2–3). Because they had placed their own interests first, God sent them famine as a judgment (Hag 1:5–6, 10–11). Spurred by the preaching of Haggai and Zechariah, and under the leadership of Zerubbabel and Joshua, a new effort was begun (Hag 1:12–15). The reference to “Artaxerxes” seems out of place because this king did not contribute to the rebuilding of the temple. His name may have been inserted here because he contributed to the work of the temple at a later date during the time of Ezra (7:21–26).

15 “Adar,” the last Babylonian month, was February-March. The temple was finished on March 12, 515 B.C., a little over seventy years after its destruction. As the renewed work on the temple had begun Sept 21, 520 (Hag 1:4–15), sustained effort had continued for over four years. According to Hag 2:3, the older members who could remember the splendor of Solomon’s temple were disappointed when they saw the smaller size of Zerubbabel’s temple (cf. 3:12). Nonetheless the second temple, though not as grand as the first, lasted much longer.

The general plan of the second temple resembled the first. But “the Most Holy Place” was left empty as the ark of the covenant had been lost through the Babylonian conquest. The “Holy Place” was furnished with a table for the showbread, the incense altar, and one menorah instead of Solomon’s ten.

7. The dedication of the temple (6:16–18)

16 For the dedication of Solomon’s temple, see 1Ki 8. This verse and v.19 emphasize that the leadership of the returned exiles was responsible for the completion of the temple. This dedication of the temple was a joyous occasion. The Jewish holiday in December that celebrates the discovery of pure oil, its prolongation, and the rededication of the temple captured by the Jews by the Maccabees is known today as Hanukkah.

17 The number of victims sacrificed was small compared to the thousands in similar services under Solomon (1Ki 8:5, 63), Hezekiah (2Ch 30:24), and Josiah (2Ch 35:7). Nonetheless, they represented a real sacrifice under the prevailing conditions.

18 This ends the Aramaic section that began in 4:8; another Aramaic section begins at 7:12. The priests were divided into twenty-four courses, each of which served at the temple for a week at a time (cf. Lk 1:5, 8).

8. The celebration of the Passover (6:19–22)

19 The date would have been about Apr 21, 515 B.C. Since the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70, Jews have not sacrificed Passover lambs but have substituted eggs and roasted meat. Only the Samaritans continue to slaughter lambs, for their place of worship is on Mount Gerizim (cf. Jn 4:20), though their temple has also been destroyed.

20 “Ceremonially clean” (GK 3196) is used almost exclusively of ritual or moral purity, especially in OT passages relating to the priests. Priests and Levites had to be cleansed in order to fulfill their ritual functions. In 2Ch 29:34, the Levites in the time of Hezekiah are described as more upright in heart in sanctifying themselves than the priests (2Ch 30:17–19).

21 The returning exiles were not uncompromising separatists; they were willing to accept any who would separate themselves from the syncretism of the foreigners introduced into the area by the Assyrians. “The unclean practices” are literally “uncleanness,” “filthiness.” Idolatry had defiled the land (Eze 36:18; cf. Ge 35:2), and the Israelites were unclean because of it (cf. Eze 22:4; 36:25).

22 The joy experienced here was more than a political celebration or a displaced person’s gladness at his return home. This was a deeply religious joy “because the Lord had filled them with joy.” “King of Assyria” is a surprising title for Darius, the Persian king. Assyria was originally in the area in northeastern Mesopotamia along the banks of the upper Tigris River, centering around its capital, Nineveh. After the fall of that city in 612 B.C., the term “Assyrian” was used for formerly occupied territories. Persian kings adopted a variety of titles, including “king of Babylon” (cf. 5:13; Ne 13:6). In Ne 9:32 “kings of Assyria” could signify, not only Assyrian, but also Babylonian and Persian kings. The latter meaning may be intended here.

II. Ezra’s Return and Reforms (7:1–10:44)

A. Ezra’s Return to Palestine (7:1–8:36)

1. Preparations (7:1–10)

1 “After these things” refers to the completion and dedication of the temple in 515 B.C. (cf. ch. 6). The identity of the Artaxerxes mentioned here has been disputed. If this was Artaxerxes I, as the traditional view maintains and which we believe is correct, Ezra arrived in Palestine in about 458. This view assumes a gap of almost sixty years between the events of chs. 6 and 7. The only recorded event during this interval concerns opposition in Xerxes’s reign (485–465 B.C.; cf. 4:6).

The genealogy of Ezra given in vv.1–5 is an extraordinary one that lists his ancestors back to Aaron, brother of Moses. “Ezra” is a shortened form of Azariah, a name that occurs twice in the list of his ancestors. “Seraiah” (“The LORD is Prince”) was the high priest under Zedekiah who was killed in 587 B.C. by Nebuchadnezzar (2Ki 25:18–21; Jer 52:24), some 129 years before Ezra’s arrival. “Azariah” (“The LORD has helped”) is the name of about twenty-five OT individuals, including one of Daniel’s companions (Da 1:6–7). “Hilkiah” (“My portion is the LORD”) was the high priest under Josiah (2Ki 22:4).

2 On “Shallum” see comment on 2:42. “Zadok” (“righteous”) was a priest under David whom Solomon appointed chief priest in place of Abiathar, who had supported the rebel Adonijah (1Ki 1:7–8; 2:35). Ezekiel regarded the Zadokites as free from idolatry (Eze 44:15–16). The Zadokites held the office of high priest till 171 B.C. The Sadducees were named after them, and the Qumran community looked for the restoration of the Zadokite priesthood.

3–4 “Amariah” means “The LORD has spoken”; “Zerahiah,” “The LORD has shone forth”; “Uzzi,” “[The LORD is] strength”; and “Bukki,” “vessel [of the LORD].”

5 “Abishua” (“My father is salvation”) was the great grandson of Aaron (1Ch 6:4–5); “Phinehas” (“the Nubian”), his grandson. “Eleazar” means “God has helped.”

6 “A teacher” (lit., “scribe”; GK 6221) is a person who served as secretary, such as Shaphan under Josiah (2Ki 22:3). Others took dictation, as Baruch, who wrote down what Jeremiah spoke (Jer 36:32). From the exilic period the scribes were scholars who studied and taught the Scriptures. In the NT period they were addressed as “rabbis.” “The hand of the LORD his God was on him” is a striking expression of God’s favor.

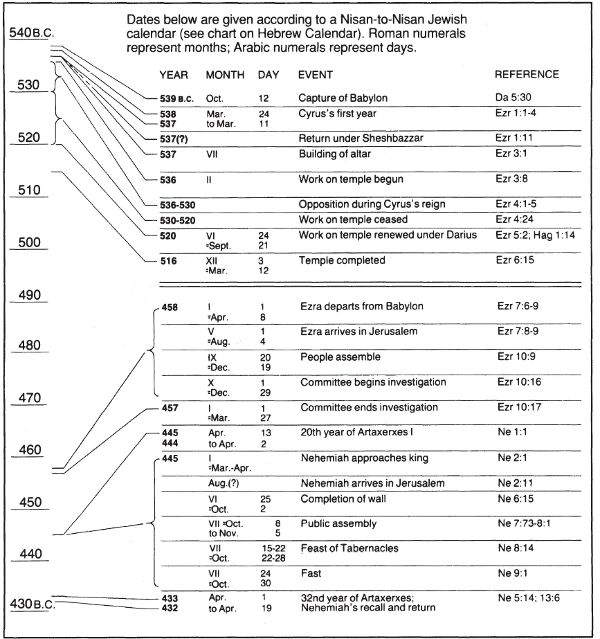

7–9 Most scholars assume that the seventh year of Artaxerxes I should be reckoned according to the Persian custom of dating regnal years from spring to spring (Nisan to Nisan, which was also the Jewish religious calendar). Thus Ezra would have begun his journey on the first day of Nisan (Apr 8,458) and arrived on the first day of Ab (Aug 4,458). The journey took 119 days (including an eleven-day delay, cf. 8:31), or four months.

Spring was the most auspicious time for such journeys; most ancient armies went on campaigns at this season. Though the direct distance between Babylon and Jerusalem is about five hundred miles, the travelers would have had to traverse nine hundred miles, going northwest along the Euphrates River and then south. The relatively slow rate is explicable by the presence of children and the elderly. The full phrase “the gracious hand of his God was on him” occurs here, in 8:18, 22, and in Ne 2:8, 18. This phrase denotes God’s permanent help and grace that rest on a person or a congregation.

10 Ezra was learned in the law of Moses (v.6), as a “teacher of the Law of the God of heaven” (v.12). He not only studied the Scriptures but taught and interpreted them (Ne 8). Bible study was not merely an intellectual discipline butit was also a personal study for his own life and for the instruction of his congregation.

2. The authorization by Artaxerxes (7:11–26)

11 Many scholars regard the letter of Artaxerxes I permitting Ezra’s return in 458 (or 457) as the beginning point of Daniel’s first 69 weeks (Da 9:24–27). If each week represented a solar year, then 69 times 7 years equals 483 years, added to 457 B.C. equals A.D. 26, i.e., the traditional date for the beginning of Christ’s ministry. Others, however, regard the commission of the same king to Nehemiah in 445 B.C. as the starting point (Ne 1:1, 11; 2:1–8). From this date, by computing according to a lunar year of 360 days, the same date of A.D. 26 is reached.

12 The text of the decree in vv.12–26 is in Aramaic. The phrase “king of kings” was used by Assyrian kings, as their empires incorporated many kingdoms. It was then adopted by Neo-Babylonian kings like Nebuchadnezzar (Eze 26:7; Da 2:37, 47). The rabbis applied to God the title “King of the king of kings.”

13–14 The king used the term “Israelites” rather than “Judeans.” Ezra’s aim was to make a united Israel of those who returned. “Seven advisers” corresponds with known Persian tradition. Many scholars believe that “the Law” Ezra brought with him was the complete Pentateuch in its present form.

15–17 Critics ask whether the Persian king would be so generous. The Persian treasury had ample funds, and such benevolence was a well-attested policy. The custom of sending gifts to Jerusalem from the Jews in the Diaspora continued down through the Roman Empire till the Jewish-Roman War, when the Romans diverted these contributions to the temple of Jupiter instead.

18–19 See comments on 5:17 and 6:1.

20–21 There are over three-hundred travel texts from Persepolis, which report the daily operations of a highly developed system of travel, transport, and communication. Other Elamite texts from the treasury at Persepolis give examples of the royal disbursement of supplies and funds. Haggai 1:8–11 indicates that work on the temple was delayed because of a lack of contributions from the Jewish community. Perhaps the provincial officials did not cooperate in carrying out the royal commands.

22 A “talent” (lit., “circle”; GK 3970–71) in the Babylonian sexagesimal system was 60 minas, with a mina being 60 shekels. A talent weighed about 75 pounds. A hundred talents was an enormous sum, about 3 3/4 tons of silver. This amount, together with a talent of gold, was the tribute that Pharaoh Neco imposed on Judah (2Ki 23:33). A “cor” was a donkey load, about 6 1/2 bushels. The total amount of wheat, 650 bushels, was relatively small. The grain would be used in meal offerings. A “bath” was a liquid measure of about 6 gallons; therefore, the amount of oil was 600 gallons. “Salt without limit” is literally “salt without prescribing [how much]” (see comments on 4:14; 6:9).

23 The Persian king expressed urgency in his command. “Wrath against the realm of the king” hints at Egypt’s revolt against the Persians in 460 B.C. and Egypt’s temporary expulsion of the Persians in 459 with the aid of the Athenians. In 458 (457) when Ezra returned to Palestine, the Persians were involved in suppressing the revolt. We do not know how many “sons” the king had at this time, but he ultimately had eighteen.

24 In the ancient world, priests and other temple personnel were often given exemptions from enforced labor or taxes.

25 Royal judges under the Persians had life tenure but were subject to capital punishment for misconduct in office. Ezra was told to administer justice according to Jewish (OT) laws.

26 The extensive powers given to Ezra—“must surely be punished by death”—are striking. Possibly the implementation of these provisions involved Ezra in much traveling, which would explain the Bible’s silence about his activities between 458 and 445. Other documents show that it was Persian policy to encourage both moral and religious authority that would enhance public order.

3. Ezra’s doxology (7:27–28)

27–2S Here is the first occurrence of the first person for Ezra, a trait that characterizes the “Ezra Memoirs” that continue to the end of ch. 9. “Praise” (lit., “blessed”; GK 1384) opens the prayers that Jews recite today: “Blessed art Thou, O Lord our God.” Ezra recognized fully that the ultimate source of the favor granted by the king was the sovereign grace of God (cf. 6:22). “To bring honor” can mean “to glorify.” Human beings can beautify, but only God can endow with true glory. Later passages show that Ezra was primarily a priest and scholar rather than an administrator. Yet the assurance that God had called him and had opened the doors gave Ezra the courage and strength to undertake this great task.

4. Returnees with Ezra (8:1–14)

1 Verses 1–14 list those who accompanied Ezra from Mesopotamia, including the descendants of 15 individuals. The figures of the men listed total 1,496, in addition to the individuals named. There were also a considerable number of women and children (v.21). An additional group of about 40 Levites (vv.18–19) and of 220 “temple servants” (v.20) are also listed.

2 On “Phinehas” see 7:5. “Gershom” (“sojourner”) was also the name of the elder son of Moses and Zipporah (Ex 2:22). “Ithamar” (“isle of palms”) was also the name of the fourth son of Aaron (Ex 6:23).

3 “Shecaniah” means “The LORD has taken up his abode.” “Zechariah” (“The LORD has remembered”) was the name of about thirty individuals in the Bible, including the prophet and the father of John the Baptist (Lk 1:5–67).

4–6 “Jahaziel” means “May God see!” “Ebed” (lit., “slave”) is probably a shortened form of “Obadiah” (“slave of the LORD”). “Jonathan” (“The LORD has given”) is the name of sixteen individuals in the OT.

7–9 On “Elam” see 2:7. “Jeshaiah” means “The LORD has saved.” “Athaliah” (“The LORD is exalted”) was also the name of a famous queen, daughter of Ahab and Jezebel (2Ki 11). On “Shephatiah” see 2:4. “Zebadiah” means “The LORD has given.” “Michael” (“Who is like God?”) is the name of ten OT individuals, including the archangel. “Joab” means “The LORD is father.” “Jehiel” means “May God live!”

10–12 “Josiphiah” (“May the LORD add!”) appears only here, but it is a name closely related to Joseph. On “Zechariah” see v.3. On “Azgad” see 2:12.

13–14 “The last ones” probably implies that these followed earlier members of the family who came with Zerubbabel. “Eliphelet” means “(my) God delivers.” “Jeuel” is “The LORD has stored up.” “Shemaiah” (“The LORD has heard”) is the name of twenty-eight individuals in the Bible. On “Bigvai” see 2:2.

5. The search for Levites (8:15–20)

15 “The canal that flows toward Ahava” probably flowed into either the Euphrates or the Tigris. “Three days” would be from the ninth to the twelfth of Nisan, as the actual journey began on the twelfth (cf. v.31). The “Levites,” who had been entrusted with many menial tasks, may have found a more comfortable way of life in exile.

16 “Eliezer” means “my God is help.” “Ariel” (“Lion of God”) appears only here as a personal name (cf. 2Sa 23:20; 1Ch 11:22); elsewhere it is a cryptic name for Jerusalem (Isa 29:1, 2, 7). “Meshullam” (“rewarded”) is the name of nineteen OT individuals. He may be the same person who opposed the marriage reforms (10:15). “Men of learning” is literally “those who cause to understand” (cf. 1Ch 25:8; 2Ch 35:3; Ne 8:7–9).

17–18 “Iddo” means “strength.” “Sherebiah” possibly means “The LORD has sent scorching heat.” “A capable man” is literally “a man of insight.” “Mahli” means “shrewd.”

19 “Hashabiah” (“The LORD has taken account”) is the name of eleven OT individuals, primarily Levites. “Merari” means “bitterness.” Only about forty Levites from two families were willing to join Ezra’s caravan. The service of God requires dedication and sometimes moving from a comfortable situation.

20 On “temple servants” see comment on 2:43. Humanly speaking, the dedication of this group is remarkable. Socially they were a caste of mixed origins and were inferior to the Levites in status. But God’s Spirit had motivated them to respond in larger numbers than the Levites.

6. Prayer and fasting (8:21–23)

21 For the association of fasting and humbling oneself, see Ps 35:13. Ezra prayed for a journey unimpeded by obstacles and dangers (cf v.31). “Children” designates those younger than twenty, with a stress on the younger ages. Such “little ones” are most vulnerable in times of war (cf. Dt 20:14; Jdg 21:10; Eze 9:6). The vast treasures they were carrying—“our possessions”—offered a tempting bait for robbers.

22 Scripture speaks often of unholy shame (Jer 48:13; Mic 3:7) and sometimes of a sense of holy shame. Ezra was quick to blush with such a sense of holy shame (cf. 9:6). He had gone out on a limb by proclaiming his faith in God’s ability to protect the caravan. Having done so, he was embarrassed to ask for human protection. Grave dangers faced travelers between Mesopotamia and Palestine. Some thirteen years later Nehemiah was accompanied by an armed escort (see comment on Ne 2:9). For the phrase “everyone who looks to him,” see 1Ch 16:10–11; 2Ch 11:16; Pss 40:16; 69:6; 70:4; 105:3–4.

23 Fasting implies an earnestness that makes one oblivious to food. For the association of fasting and prayer, see Ne 1:4; Da 9:3; Mt 17:21 (NIV note); Ac 14:23.

7. The assignment of the precious objects (8:24–30)

24 This rendering implies that Sherebiah, Hashabiah, and ten others were the twelve leading priests. But according to vv.18–19, they were the leaders of the Levites at Casiphia. The verse can be rendered “I set apart twelve of the leading priests besides Sherebiah, Hashabiah, and ten of their brothers” (emphasis mine). According to v.30, both priests and Levites were entrusted with the sacred objects.

25 “Offering” literally means “what is lifted” (i.e., “dedicated” or “given for the cult”; cf. Ex 25:2; 35:5; Lev 7:14; Dt 12:6). The offerings came not only from the Jews but also from the king.

26–28 For comparison “650 talents” equals 49,000 pounds or close to 25 tons of silver (cf. 7:22). “100 talents” equals 7,500 pounds. These are enormous sums, worth millions of dollars. On “darics,” see comment on 2:69 (cf. Ne 7:70–72). “Polished bronze” may have been orichalc, a bright yellow alloy of copper highly prized in ancient times.

29–30 Both people and objects were sacred and “consecrated” (GK 7731) to God. Ezra carefully weighed out the treasures and entrusted them to others. He instilled a sense of the holiness of the mission and the gravity of each individual’s responsibility. Each was responsible to guard his deposit, his “talent.” The data were carefully recorded and rechecked at the journey’s end (v.34).

8. The journey and arrival in Jerusalem (8:31–36)

31–32 “We set out” means literally “to pull up stakes” (i.e., of tents). After an initial three-day encampment (v.15), another eight days elapsed while Levites for the caravan were gathered. The actual departure was on the twelfth day. The journey was to take four months (see comment on 7:9). Nehemiah also “rested three days” after his arrival in Palestine (Ne 2:11).