INTRODUCTION

1. Background

Israel’s idolatrous abominations caused the ten northern tribes of that nation to be taken into captivity by Assyria in 722 B.C. At that time the southern kingdom of Judah was spared through the influence of righteous men like Isaiah. Judah soon experienced a revival and spiritual refreshment under the leadership of young King Hezekiah. He had learned the spiritual lessons from the downfall of Israel and was encouraged by the ministry of the prophet Isaiah (2Ki 18–19). However, Hezekiah’s faith in the Lord and zeal for the Mosaic covenant were forgotten when his son Manasseh and his grandson Amon rejected the ways of the Lord. For fifty-five years (2Ki 21:1–18) they turned the people to all kinds of idolatry and wickedness. This so perverted the people that they repudiated the law of God and forgot that it existed.

Josiah, Amon’s righteous son, brought renewed hope to Judah; but it came too late. As he was having the temple repaired, a copy of the Law of Moses was discovered (2Ki 22). On reading it, Josiah was moved to obey it fully (2Ki 23). He purified the temple and officially cleansed the land of the abominations of Manasseh and Amon. But among the people this reformation was only perfunctory. The idolatry of Manasseh’s long reign had so corrupted their hearts that there was little genuine repentance (cf. Jer 3:10). The Mosaic covenant declared that the nation of Israel would be taken captive and dispersed among the nations if the people continually disobeyed the stipulations of that covenant (Lev 26; Dt 28–29). That curse was now certain. It was the only thing that would remove the wickedness of Israel and cause the people to return to the Lord their God.

Meanwhile, on the international scene there was a new power struggle. Assyria, the dominant nation in the ancient Near East for more than 250 years, was declining, while the Neo-Babylonian Empire was rising under the leadership of Nabopolassar. In 612 B.C. the Babylonians defeated the Assyrians; and Nineveh, their capital city, fell. The remnants of the Assyrian army under Ashuruballit II retreated westward to Haran, where, with their backs to the Egyptians, they endeavored to keep resistance alive.

In 609 B.C. Pharaoh Neco of Egypt marched to the aid of Assyria with a large force. At Megiddo, Josiah, the reformer king of Judah, tried to stop the advance of Neco, only to be killed in the ensuing battle. Neco continued on to Haran to support Ashuruballit in his attempt to retain Haran, but the strength of the Babylonians gave them a decisive victory.

Though Neco failed in his effort to aid Assyria at Haran, he did begin to consolidate Palestine and Aram. He removed Jehoahaz, the pro-Babylonian son of Josiah whom the people of Judah crowned as their new king, and established Jehoiakim, Josiah’s eldest pro-Egyptian son, as his vassal king in Judah. Throughout this international turmoil, Jeremiah the prophet warned the people of Judah to submit to the Babylonians and not to follow the enticements of Egypt. But they would not listen.

In 605 B.C. Nebuchadnezzar, the crown prince of Babylonia, attacked the combined Assyrian and Egyptian forces at Carchemish on the Euphrates in one of the most important battles of history. In Nebuchadnezzar’s overwhelming victory, two great powers of the ancient Near East fell, never again to rise to international significance. As the Babylonians pushed their conquest southward, they invaded Judah and deported a group of young nobles from there (2Ki 24:1; 2Ch 36:6; Da 1:1–3, 6). This began the great Babylonian captivity of Judah that would ultimately affect every Israelite.

Jehoiakim was both a reluctant vassal of Babylon and a greedy ruler over his people, despising the Mosaic covenant and the reforms of his father, Josiah (Jer 22:13–17). After three years of unwilling submission to Nebuchadnezzar, Jehoiakim refused to heed the warnings of Jeremiah and revolted against Babylon in favor of Egypt (2Ki 24:1). The stalemate in battle between Babylon and Egypt on the frontier of Egypt in 601 B.C. encouraged him. His revolt was a mistake, for as soon as Nebuchadnezzar reorganized his army, he retaliated against those nations that had revolted and had refused to pay tribute to him.

In December 598 B.C., during the month that the Babylonians began to attack Judah, Jehoiakim died. His eighteen-year-old son, Jehoiachin, succeeded him (2Ki 24:8), only to surrender the city of Jerusalem to Nebuchadnezzar three months later. Jehoiachin, his mother, his wives, his officials, and the leading men of the land (2Ki 24:12–16), including Ezekiel (a priest; Eze 1:1–3), were led away into exile. Zedekiah, Jehoiachin’s uncle, was established by Nebuchadnezzar as a regent vassal over Judah. Though in exile, Jehoiachin remained the recognized king of Judah by Babylon, as demonstrated from administrative documents found in the excavations at Babylonia.

Buoyed by false prophets’ messages that Nebuchadnezzar’s power was soon to be broken and the exiles would triumphantly return, and seduced by the seemingly renewed strength of Pharaohs Psammetik II (594–588 B.C.) and Apries (588–568 B.C.), on whom the vacillating Zedekiah pinned his hopes of restored national independence, the king was persuaded to rebel once more against Nebuchadnezzar. The response of Babylon was immediate. Early in 588 the Babylonian army laid siege to Jerusalem (2Ki 25:1; Jer 32:1–2), having already destroyed the fortress cities of the Judean hill country (vividly described in the Lachish Letters). In the fall of 586, Jerusalem was destroyed; Zedekiah was captured and blinded after witnessing the execution of his sons; many inhabitants of Jerusalem were murdered by the Babylonians; and others were deported to Babylon (2Ki 25:2–21; Jer 52:5–27). Judah had fallen.

During this period of international turmoil and unrest, combined with the immorality and apostasy of Judah, Ezekiel ministered. Having grown up during the reform of Josiah and having been taken captive in the deportation of Jehoiachin in 597 B.C., Ezekiel proclaimed to the exiled Jews the Lord’s judgment and ultimate blessing.

The following outline will clarify the chronological relationship between the Judean, Egyptian, and Babylonian kings.

1. Judean kings

Josiah (640–609 B.C.)

Jehoahaz (Josiah’s second son) (609 B.C.)

Jehoiakim (Josiah’s eldest son) (609–597 B.C.)

Jehoiachin (Jehoiakim’s son) (597 B.C.)

Zedekiah (Josiah’s youngest son; a regent) (597–586 B.C.)

Jerusalem destroyed (586 B.C.)

2. Egyptian kings

Psammetik I (664–609 B.C.)

Neco (609–594 B.C.)

Psammetik II (594–588 B.C.)

Apries (Hophra) (588–568 B.C.)

3. Neo-Babylonian kings

Nabopolasser (626–605 B.C.)

Nebuchadnezzar (605–562 B.C.)

2. Authorship and Date

Ezekiel’s authorship of the entire book was never seriously questioned before the second quarter of the twentieth century. Recent objections to the book’s unity have been based on critical literary analysis. Though Ezekiel’s visions caused him to see events in Jerusalem while living in Babylon, there are fewer difficulties in accepting the traditional unity than in altering the text and devising stylistic, geographical, and historical objections. The style and content of Ezekiel are remarkably consistent. Some hold to a Palestinian locale for the composition.

Few books in the OT place as much emphasis on chronology as Ezekiel does. The first three verses of ch. 1 mark the chronological setting, dating the book by Jehoiachin’s deportation to Babylon in 597 B.C. The first prophetic message is dated in “the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin” (1:2; i.e., 593 B.C.), and the last-dated message (29:17–30:19) was given in “the twenty-seventh year” (571 B.C.) The book contains thirteen chronological notices. Chapters 1–24, which announce both the judgment on Jerusalem and Judah and the basis for it, are dated 593–589 B.C. (1:1–3; 8:1; 20:1; 24:1). The prophecies against the foreign nations in chs. 25–32 are dated 587–585 B.C. (26:1; 29:1; 30:20; 31:1; 32:1, 17), with the exception of 29:17–30:19. The messages of blessing and hope in chs. 33–48 were delivered between 585 and 573 B.C. (33:21; 40:1).

3. Place of Origin and Destination

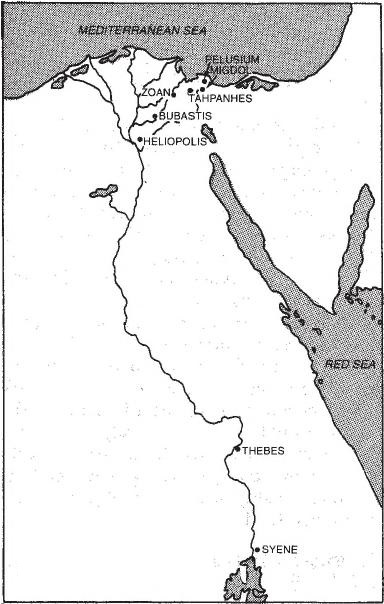

Ezekiel 1:1–3 and 3:15 clearly define the place of origin of Ezekiel’s ministry as Babylonia, specifically at the site of Tel Abib located near the Kebar River and the ancient site of Nippur. Many identify this “River” as a canal making a southeasterly loop, connecting at both ends with the Euphrates River.

The conditions of the Jews in the Babylonian exile were not severe. Though placed at the specific site of Tel Abib, it seems that they had freedom of movement within the country and the opportunity to engage in commerce. They were regarded more as colonists than slaves.

Ezekiel’s messages were primarily for these exiles. He condemned the abominations that were leading Jerusalem and Judah to ultimate destruction. The exiles questioned the prophecies of Ezekiel; and he, in turn, answered them carefully. He played the role of a watchman to warn them of the impending judgment on Judah and to proclaim the hope of their ultimate restoration to the land of Israel. Though in some of Ezekiel’s visions (chs. 8 and 11) he was carried to Jerusalem, his messages were not directly given for the benefit of the Jews in Palestine. The distance between Babylon and Jerusalem would preclude these messages being directed to Jerusalem, though certainly some of the concepts of Ezekiel may have filtered back to Palestine. Jeremiah, Ezekiel’s contemporary, however, was simultaneously proclaiming a similar message of warning and judgment to those remaining in Jerusalem and Judah.

4. Occasion and Purpose

When God created the nation of Israel, he gave the people the Mosaic covenant (Ex 20–Nu 9; Dt) as their constitution, which told them how to live for the Lord. The law was not given to burden the Hebrews; it was given for their own good (Dt 10:12–13), so that they might be blessed (Dt 5:28–33).

Yet the history of Israel was marked by disobedience to this covenant. Often the nation followed the gods of the peoples around them. As the above historical sketch shows, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah became increasingly corrupt and ultimately forgot their constitution. The covenant itself had warned the Israelites that if they strayed from the Lord’s ways revealed in the statutes and commandments of the law, the Lord would discipline them through dispersion in order to bring them back to himself.

Ezekiel spoke to his contemporaries, declaring to them the faithfulness, holiness, and glory of God. Their God would bring judgment, cleansing, and ultimate blessing through which all peoples might come to know that he, the God of Israel, was the one true God. The Lord desired to turn the exiles of Israel away from their sinful ways and restore them to himself. His judgment, therefore, was exercised as an instrument of love to cause them to see their abominations and to recognize the Lord’s faithfulness to his covenants. He was indeed faithful to his promises, both to judge and to bless his people. The destruction of the city of Jerusalem demonstrated God’s faithfulness to his holy character (cf. Lev 26; Dt 28–30) as revealed in his covenants. On the other hand, Ezekiel gave hope that one day the true Shepherd, the Messiah, would come to lead God’s people. Though their contemporary rulers had exploited them and led them away from the Lord, in the future the people would be restored to the Promised Land (Ge 12:7) by a righteous leader. In that day all the covenants of the Lord would be fulfilled to his people (Eze 37:24–28).

Ezekiel, as a watchman for Israel, warned the people of the judgment that was imminent and stressed the need for individual responsibility as well as national accountability before God. Each Israelite was personally to turn to the Lord. Likewise, the whole nation must ultimately return to him.

5. Theological Values

Five prominent theological concepts pervade these prophetic pages: (1) the nature of God; (2) the purpose and nature of God’s judgment; (3) individual responsibility; (4) the ethical, religious, and moral history of Israel; and (5) the nature of Israel’s restoration and the millennial worship.

(1) God’s attributes most strongly emphasized are those relating to his covenant promises. A righteous and holy God had established a righteous way of life for the well-being of his people. If they followed the stipulations of that covenant, they would be blessed in every spiritual and physical way (Lev 26:3–13; Dt 28:1–14). If they rebelled against the Lord’s righteous ordinances and disobeyed them, the Lord—being holy, just, and righteous—would discipline his people and withhold blessing (Lev 26:14–39; Dt 28:15–68). Ezekiel demonstrated the Lord’s faithfulness to these promises. He was judging Israel and Judah because they had broken the law, but he would also faithfully restore the people to the land of blessing and confer on them messianic blessings of the Abrahamic, Davidic, and new covenants (Lev 26:40–45; Dt 30; cf. Ge 12:1–3; 2Sa 7:12–17; Jer 31:31–34).

(2) God’s character logically reflects judgment. The Lord loved the Israelites and chose them as his very own people to bless the world (Ge 12:2–3; Ex 19:4–6; Dt 7:6–11). Since they strayed from his righteous ways, the Lord brought judgment on them to make them conscious of their wickedness so that they would return to him. Ezekiel continually declared that the purpose of the Lord’s judgment was to cause Israel, or the nations, to “know that I am the LORD,” a phrase repeated over sixty-five times in this book. Judgment was for Israel’s good because it would result in their return to the Lord and their recognition that he was the only true God.

(3) Though the Lord often dealt with Israel nationally, Ezekiel balanced this with an emphasis on individual responsibility (cf. Dt 24:16; 29:17–21). A person was not delivered from God’s curse by the righteousness of the majority of the nation or some other person’s spirituality. Each person was accountable individually to God. Each person needed to obey the statutes of God’s word in order to live righteously before him. Everyone was equally responsible for his or her own disobedience and unrighteousness. Therefore Ezekiel exhorted the exiles to turn from their sinful ways and live righteously, according to the Mosaic covenant (chs. 18; 23).

(4) Along with God’s judgment announced in this prophecy, Ezekiel vindicated the Lord’s righteous justice by recounting Israel’s ethical, moral, and religious history. This was most vividly accomplished through the imagery of Israel as a spiritual prostitute who, having been wooed and married by God, had prostituted herself by going after the gods of other nations throughout her entire history. This idolatry and unfaithfulness had characterized her from her birth in Egypt.

(5) In spite of Israel’s consistent idolatry, the Lord gave a message of hope through his prophet. One of the most complete descriptions of Israel’s restoration to the land of Palestine in the end times was given in the hope messages (33:21–39:29), which enunciated the basis, manner, and results of Israel’s restoration to the Promised Land. Likewise, the most exhaustive delineation of the worship system in the Millennium is set forth in chs. 40–48. Anyone studying eschatology must know these sections of Ezekiel.

EXPOSITION

I. Ezekiel’s Commission (1:1–3:27)

A. The Vision of God’s Glory (1:1–28)

1. The setting of the vision (1:1–3)

1–3 The setting of the Mesopotamian dream-visions, which occurred in both the Assyrian period and the Babylonian period, consisted of four elements: the date, the place of reception, the recipient, and the circumstances. Ezekiel included all four aspects in his vision.

The date of this vision is stated in two different ways: “in the thirtieth year, in the fourth month on the fifth day,” and “on the fifth of the month—it was the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin.” The “thirtieth year” most likely relates to the age of Ezekiel. It was not uncommon that dates were given according to a man’s age when personal reminiscences were being reported (cf. Ge 8:13). Additionally, Ezekiel was a priest, and a man entered his priestly ministry at the age of thirty (Nu 4:3, 23, 30, 39, 43; 1Ch 23:3). Therefore, Ezekiel apparently received this vision and his commission in the very year he would have begun his priestly service.

The “thirtieth year” of Ezekiel is related to the fifth year of King Jehoiachin’s exile. The month is understood in v.2 from the explicit statement in v.1 (i.e., the fourth month). Since Jehoiachin was deported to Babylonia in 597 B.C., Ezekiel’s commission must have been received in 593 B.C. Jehoiachin’s year of deportation is the focal point of all dating within the book.

Ezekiel saw this vision “by the Kebar River in the land of the Babylonians.” The river Kebar, a navigable canal, flowed southeast from the city of Babylon.

Ezekiel was the stated recipient of the vision. He was a priest and the son of Buzi. Nothing is known about Buzi, though as Ezekiel’s father he would also have been a priest. The notation of Ezekiel’s priesthood is significant. He would have been well acquainted with the Mosaic covenant and the priestly functions of the temple, both of which pervade the entire message of this book. Ezekiel was able to describe clearly the glory of God in the temple and the temple functions. He also was prepared to evaluate accurately the rebellion of his people against the explicit commands of the law, which was the basis for the Lord’s judgments that Ezekiel announced. Moreover, this priestly background enabled Ezekiel to understand the millennial temple vision that concludes the entire prophecy.

The only circumstances set forth in this introduction to the subsequent vision were that “the word of the LORD came to Ezekiel” and “the hand of the LORD was upon him.” These phrases occur whenever Ezekiel was about to receive or proclaim a revelation from God (3:22; 8:1; 33:22; 37:1; 40:1). “The hand of the LORD was upon him” connotes the idea of God’s strength on behalf of the person involved (3:14), a concept inherent in the name “Ezekiel” (which means “God strengthens”). God was preparing Ezekiel to receive a vision that would provide the necessary framework for understanding the rest of the prophecy. It is important to the interpretation of this book to notice the phrase “I saw visions of God,” for this immediately declared the nature of the following vision.

2. The description of the vision (1:4–28)

a. The living beings (1:4–14)

There appears to be a general pattern to the commission narratives of the prophets. First is the divine confrontation—an introductory word that forms the basis and background for the succeeding commission. Then the commission itself enumerates the task the prophet is called to and its importance. Third, the objections the prophet may offer are stated, after which the “call” narrative closes with reassurances from the Lord that answer these objections and assure the prophet that the Lord is with him. All four elements are found in Ezekiel’s commission.

The Lord confronted Ezekiel with this glorious vision to impress on him the majesty, holiness, and wonder of the God who was about to execute judgment on the people of Israel. Ezekiel was awestruck by God’s holiness. The indelible impression of this theophany served as a constant encouragement to Ezekiel in his difficult ministry of announcing God’s judgments on his own contemporaries. Against the backdrop of the awesome holiness of God visualized here, Ezekiel saw the wickedness of Israel and thereby understood why God had to judge his sinful people. When the nations profaned the Lord by claiming that Judah was in captivity because their God was weak, Ezekiel knew that his God was greater than Babylonia’s gods. Though the Lord had chosen to discipline his people then, he would be victorious over all the nations when he restored Israel to the Promised Land.

This was the same glorious, covenant-keeping God who first revealed himself to Israel in a similar vision of splendor on Mount Sinai (Ex 19). He reappeared as the glory inhabiting the Most Holy Place in the dedication of the tabernacle (Ex 24:15–18; 29:42–46; 40:34–38). This theophany led the children of Israel through the desert (Nu 9:15–23; 14:10; 16:19; 20:6), filled Solomon’s temple (1Ki 8:10–11; 2Ch 5:14), and appeared at Isaiah’s commission (Isa 6:3). Though some may be disturbed that the manifestation of God’s glory is not always the same, variation in details is to be expected when one considers the limitlessness of God. However, the consistency of the manifestation of God’s glory was such that Ezekiel, a priest and a student of the Scriptures, immediately recognized that this was a vision of the glory of the Lord (v.28).

4–14 This vision began with a common introductory formula to visions: “I looked, and I saw.” Ezekiel suddenly saw what appeared to be a raging electrical storm—dark clouds, lightning, and thunder—coming from the north. Within this storm he saw four figures resembling living beings (cf. Rev 4), which he describes. Though the beings looked like people, each one had four faces and four wings. The human face was dominant, being on the front of each creature, while the lion’s face was on the right, the ox’s (or cherub’s; cf. 10:14, 22) face on the left, and the eagle’s face on the back.

The wings were joined together (vv.9, 23), with two covering each side of each being and the other two spread for movement, touching the wings of the other living beings (vv.11, 23). When the wings fluttered, they sounded like a great thunder of rushing water, a violent rainstorm, or a noisy military encampment—like the voice of the “Almighty” God. The sides of the living being had hands like a human being’s under its wing, straight legs, and feet like a calf.

The rapid movement of these living beings was like flashes of lightning. Their forward movement was in the direction in which the human face looked. When they moved, they did not turn around. These creatures moved only under the control of the “spirit” (v.12; GK 8120), which, in this context of God’s glory, is most likely the Holy Spirit of God.

In addition to the general appearance of brightness, these creatures contained in their midst that which looked like coals of fire, from which lightning issued. These living beings are identified in 10:15, 20 as cherubim. Certainly Ezekiel was acquainted with cherubim from his training in the temple, with its many representations of these creatures (Ex 25–26; 36–37; 1Ki 6; 2Ch 3), as well as his knowledge of the “cherubim” imagery from Mesopotamian culture with its guardian genii before temples. Cherubim often accompanied references to God’s glory in the OT; yet their specific functions are nowhere clearly delineated.

b. The wheels and their movement (1:15–21)

15–18 There was one high and awesome wheel beside each of the four living creatures (cf. 10:9) that had the general appearance of a sparkling precious stone—“chrysolite”—with a rim full of eyes (cf. Rev 4:6).

19–21 When these wheels were functioning, they gave the impression of a wheel being in the midst of another wheel. The wheels moved in conjunction with the living beings, going in any direction, lifting up off the earth, and standing still. All the movement was under the direction of “the spirit.” Chapters 3 and 10 further describe the wheels as making rumbling sounds when they whirled (3:12–13; 10:5, 13).

c. The expanse (1:22–28)

22–28 An awesome expanse resembling sparkling ice appeared like a platform over the heads of the four living creatures (cf. Rev 4:6). The likeness of a throne made from precious lapis lazuli (“sapphire”; see NIV note on v.26) was above this expanse, and the likeness of a human being was on the throne (cf. Ex 24:10; Rev 4:2). This person appeared surrounded by fire, giving him a radiance similar to a rainbow (cf. 8:2; Da 10:6; Rev 4:3, 5).

The most significant phrase of the entire chapter is in the last verse: “This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the LORD.” This reference would relate more directly to the likeness of the man on the throne, but Ex 19, 1Ki 6, Isa 6, Da 10, and Rev 4 confirm that the entire vision is a manifestation of God’s “glory” (GK 3883; cf. v.1). The Lord revealed his magnificent person to Ezekiel to prepare him for ministry. He continued to appear to Ezekiel in this same fashion throughout the book to encourage him that he was a servant of Almighty God. When one genuinely sees God’s glory, one cannot help but fall prostrate in worship before the Almighty God, as Ezekiel did.

This manifestation of the Lord’s glory forms a backdrop for the announcements of judgment that Ezekiel would make. Since the glorious, holy God who gave the Mosaic covenant (Ex 19) could not tolerate disobedience to that covenant because of his righteous character, he had to execute judgment on the iniquity that his holy nature could not tolerate. Therefore, when God brought judgment on Jerusalem, his glory had to leave its residence in the temple (10:1–20; 11:22–23). However, Ezekiel saw the Lord’s glory returning (cf. ch. 43) after the cleansing of God’s people was completed. Thus the revelation of God’s glory becomes a significant theme throughout the prophecy, showing a unity of purpose within the book.

B. The Lord’s Charge to Ezekiel (2:1–3:27)

1. The recipients of Ezekiel’s ministry (2:1–5)

1–2 The voice of God speaking from the theophany addressed Ezekiel with the title “son of man” (GK 1201 & 132). This became Ezekiel’s normal designation throughout the remainder of the book (used over ninety times); this expression is found nowhere else in the OT except in Da 7:13; 8:17. This title indicates the frailty and weakness of a human being humbled before the mighty and majestic God. By this title Ezekiel was reminded continually of his dependence on the Spirit’s power, which enabled him to receive God’s message and to deliver it in the power and authority of the Lord—“This is what the Sovereign LORD says” (v.4). This same name—“Son of Man”—was given Christ in the Gospels (Lk 19:10) to emphasize his relation to humanity and his voluntary dependence on the Spirit of God (see comments on Da 7:13–14; Mk 8:31).

3–4 The commission side of Ezekiel’s call narrative encompasses the majority of chs. 2–3. God was about to commission Ezekiel for a most difficult task. He was to go to his own people in exile, the people God described as rebellious against himself, his law, and his messengers, the prophets. This was not a new condition, for this nation had transgressed the Mosaic covenant throughout her history. God’s chosen people were “obstinate” and “stubborn” (lit., “hard-hearted” and “hard-faced”), demonstrating a strong-willed determination to resist God and his ways. Undoubtedly a major contribution to Judah’s current rebellion were the abominations of Manasseh that had stained the hearts of the people.

5 Ezekiel’s message was not to be conditioned on his listeners’ response. Even if the people closed their ears to his words, he was to speak in God’s authority and not his own. Only then would the people know that a prophet had been among them.

2. Ezekiel’s encouragement in the ministry (2:6–7)

6–7 In light of the difficult ministry Ezekiel was being called to, the Lord reassures him. Regardless of how frightful the opposition may be—pricking him as thorns or stinging him as scorpions—Ezekiel was not to be afraid or become dismayed and give up. On the contrary, he was to be faithful in proclaiming God’s message, for his recipients were rebels who needed his warnings. This truth is still a source of encouragement to those called to proclaim the truth of God’s Word in the midst of a perverse and wicked generation.

3. The nature of Ezekiel’s ministry (2:8–3:11)

2:8–3:3 The Lord’s charge to Ezekiel emphasizes the absolute necessity of hearing, understanding, and assimilating God’s message prior to going forth as a spokesman for the Lord. Ezekiel was to listen to God (2:8a) and not rebel against him, as did the people of Israel, who failed to listen to his word.

Before beginning his ministry, Ezekiel was to symbolize his complete acceptance of the Lord’s message by eating the scroll. The nature of the message he would proclaim was written on the scroll: funeral dirges, mournings, and lamentations. Certainly this was not a joyous note on which to begin. But even when the ministry would seem difficult and distasteful, the Lord would cause his word to be as sweet as honey.

4–9 The recipients’ response to Ezekiel’s messages was not to govern the nature or manner of his ministry. The people rejected the divine messenger because they had been alienated from God. Though Israel was obstinate, and though it would have been easier to preach to foreign people in a foreign language, Ezekiel was to be strong and not respond in fear and dismay. The Lord fully prepared Ezekiel for his task by making him more determined than the people of Israel—as sharp and hard as flint. The Lord always prepares and reassures his messengers with the needed equipment.

10–11 The word of the Lord had to become part of Ezekiel (cf. Jer 1:9) before he could “go” and “speak” (Eze 3:1). Thus the prophet was to meditate on the Lord’s message, giving continual attention to it throughout his ministry. Only then would he be able to speak repeatedly with God’s authority—even to audiences who did not care to listen to him.

4. The conclusion of the vision (3:12–15)

12–13 The vision concludes with Ezekiel’s being raised up by the Spirit and hearing a final benediction that assured him that he had witnessed a revelation of God’s glory. Ezekiel’s transportation was not a case of hypnotism, autosuggestion, or the parapsychic phenomenon of bodily levitation. Rather, his transportation was in a vision, experienced under the compulsion of the Holy Spirit.

14–15 These verses recount Ezekiel’s objection to his commission (the third element of the normal prophetic-call narrative; see comment on 1:1–14). As Ezekiel was brought back in the Spirit to the exiles at Tel Abib, he struggled with the distasteful ministry he had been called to. He was anguished and angry that he had to deliver a displeasing message to an unreceptive audience.

It took Ezekiel seven days to sort out his thoughts and feelings after having seen this vision. The Lord’s hand was on him to control him as he sat appalled at the wonder and horror he had experienced. Ezekiel’s condition and the period of seven days were instructive to the exiles: mourning for the dead normally took seven days (Ge 50:10; Nu 19:11; Job 2:13), as did the length of time for a priest’s consecration (Lev 8:33). Ezekiel was being consecrated for the priesthood on his thirtieth birthday and commissioned to proclaim Judah’s funeral dirge.

5. Ezekiel: a watchman to Israel (3:16–21)

16–17 Ezekiel’s basic prophetic role was to be a watchman to the house of Israel (cf. chs. 18; 33). A watchman in OT times stood on the wall of the city as a sentry, watching for any threat to the city from without or within. If he saw an invading army on the horizon or any dangers within the city like fire or riots, he would immediately sound the alarm to warn the people (2Sa 18:24–27; 2Ki 9:17–20).

18–21 Ezekiel was to listen to the Lord and then warn the people of Judah concerning judgment on the horizon. His warning was based on the Mosaic covenant (Ex 20-Nu 9; Deuteronomy), which showed those in a relationship with the Lord how to live life in the best way. The covenant’s righteous stipulations, lovingly given for the good of the people (Dt 5:28–33; 6:25; 10:12–13), enabled them to enter into all the blessings God desired to pour out on them (Lev 26:1–13; Dt 16:20; 28:1–14; Mal 3:10–12). If they disobeyed these ordinances and wandered from God’s way of living, the Lord promised that he would lovingly discipline his people to cause them to return to the righteous life he prepared for their good (Lev 26:14–39; Dt 28:15–68). Ezekiel, therefore, was to warn Israel that God’s inescapable discipline was coming.

Ezekiel’s role as a watchman (cf. Isa 56:10; Jer 6:17; Hos 9:8) was not reprobative and injurious but corrective and beneficial. He was to warn the wicked that if they did not turn from their wickedness, they would die in unrighteousness. Likewise, Ezekiel admonished the righteous not to turn from their righteous ways—loyalty to the Mosaic code—and disobey God’s commands; if they did, they would surely die. These warnings were directed to individuals.

When a righteous person turned from righteousness and did evil, God placed a “stumbling block” before him. That person had already turned from God’s ways and done evil; so this stumbling block was not placed by God deliberately to cause him to fall into sin. Rather, it was an obstacle set into the path of this person to see how he would continue to respond. If he fell, then physical death came.

If a watchman saw a potential danger to a city and failed to warn its inhabitants, he was held responsible for the following destruction. So God warned Ezekiel that if he failed to warn the people of God’s curse on disobedience, Ezekiel would be responsible for their death; Ezekiel himself would have to die for his negligence. Those charged with declaring God’s word have a weighty responsibility to be faithful.

“Life” (GK 2649) and “death” (GK 4637) in this context must be understood as physical, not eternal. The concept of life and death in the Mosaic covenant is primarily physical. That covenant was given to guide those who had already entered into a relationship with God by faith. The Hebrews could live righteously and freely by keeping these commands (Lev 18:5; Dt 16:20). But if they disobeyed, physical death, resulting in a shortened life, was the normal result (Dt 30:15–20). The emphasis was on living a righteous life. This covenant pointed the people on to faith in the Messiah, whose work for salvation is pictured in the festive and sacrificial system (cf. Heb 9:6–10:18); but the keeping of the commandments of the law never provided salvation. Throughout the Scriptures, eternal salvation is always by faith, never by works of any kind.

6. Ezekiel’s muteness (3:22–27)

22–23 Ezekiel’s commission concluded with a second glimpse of God’s glory. Ezekiel, obedient to the Lord’s command, went out to the plain where God’s glory appeared to him, as it did in the vision of ch. 1.

24–27 As Ezekiel fell down before God in true humility and reverence, the Spirit prepared him to receive the message that he was to deliver to the exiles (cf. 4:1–7:27). Ezekiel was directed to return home and shut himself up in his house. The exiles would tie him up with rope. Then the Lord would make Ezekiel mute so that he could not reprove the people unless God opened his mouth. Whenever God did so, Ezekiel would speak only in the Lord’s authority, regardless of the people’s response. The phrase “Whoever will listen let him listen” (a favorite saying of Christ) stresses individual responsibility to respond to the message.

Ezekiel’s muteness would last approximately seven and one-half years, until the fall of Jerusalem (cf. dates in 1:1–3 with 33:21–22). Yet he would deliver several oral messages in the intervening period (cf. 11:25; 14:1; 20:1). The concept of muteness, therefore, was not one of total speechlessness throughout these years. Rather, Ezekiel was restrained from speaking publicly among the people, in contrast to the normal vocal ministry of the prophets. The prophets usually moved among their people, speaking God’s message as they observed the contemporary situation. But Ezekiel would remain in his home, except to dramatize God’s messages (cf. 4:1–5:17). He would remain silent, except when God opened his mouth to deliver a message. Then his mouth would be closed until the next time that the Lord chose for him to speak. Instead of Ezekiel’s going to the people, the people had to come to him. Though this rebellious people initially rejected Ezekiel’s ministry, the elders started sneaking away to seek the Lord’s message from Ezekiel as contemporary world events began vindicating his divine warnings.

II. Judah’s Iniquity and the Resulting Judgment (4:1–24:27)

Chapters 4–24 combine a series of oral messages and symbolic acts designed to warn the people of Judah that judgment was coming and to explain the reason for this imminent discipline. In chs. 4–7 Ezekiel dramatized the coming siege of Jerusalem (ch. 4) and the subsequent dispersion of the people in exile (ch. 5). He concluded the drama by declaring that this imminent judgment would destroy pagan idolatry. The exile could not be escaped through human efforts (chs. 6–7). The vision of God’s glory reappeared to Ezekiel (ch. 8) to expose, by contrast, the defilement of Judah resulting from her current participation in idolatrous heathen rituals. Subsequently God’s glory left Jerusalem and Judah, enabling God to pour out his wrath on Israel in accord with the Mosaic covenant (chs. 9–11). The exiles objected to this, but Ezekiel effectively answered their complaints (chs. 12–19). They were reminded that their history, characterized by unfaithfulness to their Lord and spiritual prostitution promulgated by corrupt leadership (chs. 20–23), condemned them. Chapter 24 concludes by vividly describing the fall of Jerusalem.

A. The Initial Warnings of the Watchman (4:1–7:27)

1. Monodramas of the siege of Jerusalem (4:1–5:17)

a. The brick and the plate (4:1–17)

1–3 The Lord showed Ezekiel the methods he was to use in warning of the impending siege of Jerusalem and the resulting exile. Though Ezekiel was mute, God directed him to act out the warnings (probably just outside Ezekiel’s house; cf. 3:24–25). The exiles had observed Ezekiel’s unique seven-day consecration (3:15–16). Now they would wonder what strange thing he would do next. The parables Ezekiel acted out demanded an audience.

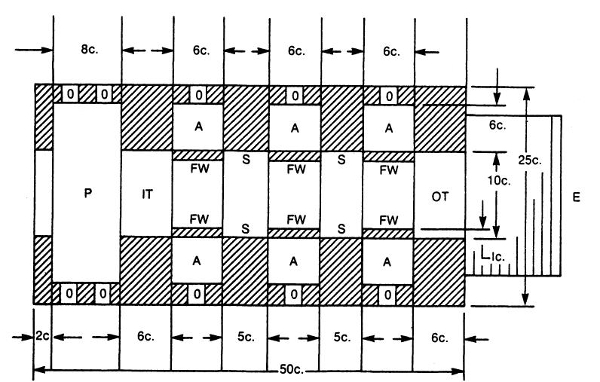

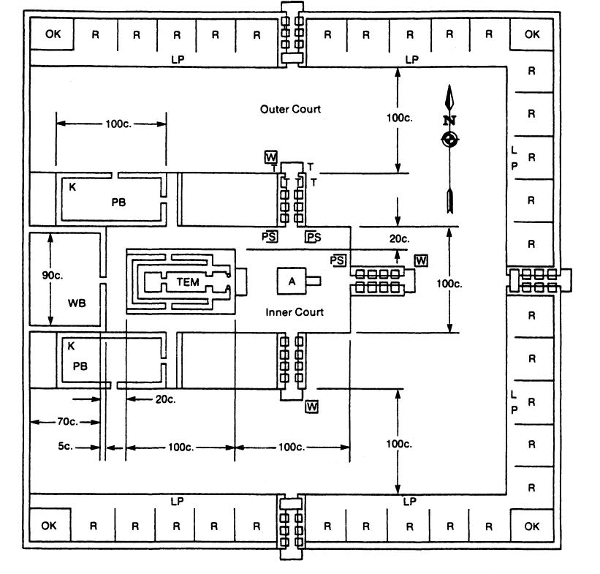

Ezekiel took a clay brick and scratched on it a diagram of Jerusalem. Then he simulated a siege of the city with “siege works,” “ramp” (or “mounds”), battering rams, and military encampments. With an iron plate between him and the city, Ezekiel played this war game with determination for 430 days while prophesying against Jerusalem (vv.6–7). All this was “a sign to the house of Israel” of the coming siege of Jerusalem.

The “iron pan” was the kind used only by the priests for certain offerings (Lev 2:5; 6:21; 7:9). It was placed between Ezekiel and the city inscribed on the clay brick. The “pan” was declared to be a “wall.” Normally walls provided protection. The Lord had warned Ezekiel of the hostile reception of his ministry (cf. 2:6). Therefore, the imagery portrays either Ezekiel’s protection as he acted out the siege or the siege wall around Jerusalem erected by the Babylonians.

4–8 After acting out Jerusalem’s siege, Ezekiel was directed to dramatize the length of time that God’s people would undergo punishment for their iniquity. He faced north first (symbolically toward Israel), lying on his left side for 390 days to represent the time for bearing the punishment for Israel’s sins. When the 390 days were “finished,” then Ezekiel would “lie down again,” this time for forty days on his right side, facing south (symbolically toward Judah), to portray the punishment for Judah’s wickedness. He would be bound in each of these positions so that he could not change sides until he had completed the allotted days to portray the siege for each nation respectively. Ezekiel need not have been on his side twenty-four hours each day. The rest of ch. 4 has him fixing meals, while in ch. 8 he sat in his house with the exilic elders during the final days of lying on his right side. Apparently a portion of each day sufficed to fulfill the symbolism.

Though the basic meaning of this section is clear, the numbers have given rise to many explanations. Certain things are plain: each day represents a year (vv.5–6; cf. Nu 14:34), and the years signify a period during which the people sinned. The numbers should be taken as literal periods of time, separated into two distinct and successive intervals of 390 and 40 years. Ezekiel’s reference point for chronological determination is Jehoiachin’s deportation of 597 B.C. This, therefore, suggests the starting point for measuring the time periods in these verses. The 430 years then denote the punishment inflicted by conquering foreign powers on the children of Israel and Judah from the deportation of Jehoiachin, their recognized king, to the inception of the Maccabean rebellion in 167 B.C. During the Maccabean period the Jews once again exercised dominion over Judah. Though this is a possible solution, we cannot be dogmatic about these numbers.

9–17 During the 390 days Ezekiel lay on his side acting out a “siege” of Jerusalem, God placed him on a strict diet. Ezekiel was to eat bread made from a mixture of several different grains. He would be rationed to two pints of water and one-half pound of bread for his daily food for over a year. This meager diet was to communicate the reality of the famine during the siege of Jerusalem. The Lord would “cut off the supply of food” in Jerusalem (as he promised in Lev 26:16, 20, 26, 29). There would be a scarcity of any one kind of grain for bread and also lack of water. The inhabitants of Jerusalem would rot away and look on one another in horror (cf. Lev 26:19, 35; 2Ki 25:3; Jer 34:17–22).

In addition to his beggarly sustenance, Ezekiel was to bake his rationed bread over a fire made unclean from human dung (cf. Dt 23:12–14). Though eating combined grains was acceptable, using human dung was defiling, for eating unclean food was forbidden by the Mosaic covenant (Lev 22:8; Dt 12:15–19; 14:21). Since Ezekiel, a faithful priest, had never eaten defiled food, he cried out to the Lord, requesting not to have to eat unclean food. God graciously permitted him to use the common fuel of cow’s dung instead of human excrement. This unclean manner of preparing food described the Captivity that would follow the imminent siege and fall of Jerusalem. The captives would eat the defiled foods of the foreign nations they would be banished to.

God was not changing his law when he told Ezekiel to do all this. God temporarily caused Ezekiel to disregard the principle of eating unclean food to dramatize in an extreme way how abhorrent the Captivity would be. God used an acted parable to convey this truth in a way that would surely be understood; the eating of unclean food as a normal practice was not being condoned here. God sovereignly protected Ezekiel against any ill effects of eating defiled food.

b. The division of hair (5:1–4)

1 Ezekiel completed the drama begun in ch. 4 by shaving his head and beard, weighing the hair, and dividing it equally into three groups. This final act also pictured defilement. Shaving the head and beard was a pagan ritual for the dead (27:31; cf. Isa 22:12; Jer 16:16; Am 8:10), which the law forbade (Dt 14:1), and a sign of humiliation and disgrace (7:18; cf. 2Sa 10:4). If an Israelite priest shaved his head, he was defiled and no longer holy to the Lord (Lev 21:5). Ezekiel defiled and humiliated himself as a symbol of the humiliation of the people of Judah who were defiled and no longer holy to the Lord. Nothing was left to do but to mourn their death as a nation.

2–4 The hair symbolized the inhabitants of Jerusalem. One-third of them would be burned when Jerusalem was burned after the siege (2Ki 25:9). Part of these people would have already died through famine and distress during the siege (v.12a). The second third of the inhabitants would die by the sword when Jerusalem fell (v.12b; 2Ki 25:18–21a; 2Ch 36:17). The final third would be scattered to the wind in exile (v.12c; 2Ki 25:11, 21b). A portion from this last group would be judged by fire as they left Jerusalem, while some would die by the sword in captivity. Out of this final third, the Lord would deliver a remnant of Jerusalem’s citizens—depicted by Ezekiel’s placing a few hairs from this group securely into the hem of his garment.

c. The significance of the symbolic acts (5:5–17)

5 The Lord emphasizes the recipient of the siege and the coming judgments by the statement, “This is Jerusalem.” Immediately one’s attention was brought back to the city etched on the clay brick in 4:1. Jerusalem was the object of God’s love. However, all these symbolic actions demonstrated what would happen to her.

6–7 A judgment speech—with accusations against Jerusalem enumerated and a verdict pronounced—reinforced the monodrama. The basic accusation was that Jerusalem, this blessed city, had responded to God’s blessing by rebelling against his commandments, refusing his ways, and failing to live life according to the Mosaic covenant. She had become so wicked that she did not even adhere to the common laws of the nations around her. Some of Jerusalem’s inhabitants would resort to cannibalism during the coming siege (v.10a; cf. Lev 26:29; Dt 28:53; 2Ki 6:28–29; Jer 19:9; La 4:10). They had already defiled his holy sanctuary with detestable idolatry (v.11a; ch. 8).

8–17 God would execute the judgments pronounced in the Mosaic covenant on Jerusalem in the sight of the nations. Never again would he execute a judgment like this. He would withdraw himself from the sanctuary (cf. 10:4; 11:22–23) to pour out his judgment without pity. One-third of the inhabitants of Jerusalem would die in the city through disease and famine; one-third would die by the sword; and a remnant would be scattered in every direction among the nations. Famine, wild beasts, plagues, and bloodshed would all be part of Jerusalem’s judgment (cf. Lev 26:21–26). The land of Judah would become a desolation, causing the nations to ridicule her because of what God had done to her. At the same time these nations would be struck with fear and terror at God’s justice and wrath even on his very own people. Judah’s judgment served to warn these nations of the judgments God would bring on them if they cursed Israel (cf. Ge 12:3). As a result of this judgment, God’s justice would be satisfied and the people of Jerusalem would know that the Lord had executed his wrath. The punishment was certain. The Lord had spoken!

2. The coming judgment on the land of Judah (6:1–7:27)

a. Destruction of pagan religious shrines (6:1–14)

1–7 God interrupted Ezekiel’s muteness to announce judgment on Judah’s mountains, hills, ravines, and valleys. Ezekiel set his face against these four geographical features of the land, for it was in them that the pagans normally established their religious shrines (cf. 2Ki 23:10). Canaanite religion—with its perverted emphasis on sex, war, cults of the dead, snake worship, and idolatry—preferred high places and groves of trees for its place of worship. Manasseh, king of Judah (695–642 B.C.), had led in the resurgence of these pagan cults.

The Lord next pronounced judgment on the heathen shrines and their cultic practices that had been adopted by his people. He would remove the temptation facing them by destroying all the “high places,” “altars,” “incense altars,” and “idols.” These shrines would become desecrated by the scattering of bones of the dead around them. The “scattering of bones” is a phrase used for judgment in which uncleanness and shame are conveyed (cf. Pss 53:5; 141:7). The bones would be those of the Israelites who had become engrossed in these pagan practices (cf. 2Ki 23:20; Jer 8:1–2). The Lord was faithful to his promise in Lev 26:30; he refused to allow anything to take his rightful place. Through this discipline Judah would know that he was the only God.

8–10 God always accompanies his pronouncements of judgment with the proclamation of a way to escape—by turning to the Lord and following his ways (cf. Jer 18:7–10). Thus within Ezekiel’s judicial sentence was the Lord’s assurance that some of the exiles would see the wickedness of their ways and be ashamed. They would remember the Lord and recognize that he did not speak in vain when he instructed his people to live righteously or they would suffer the threatened discipline. This remnant would respond to God’s discipline and repent of the spiritual fornication that had grieved the Lord. They would come to know that their God truly is the Lord. The whole purpose of God’s judgment was to bring his people back to him.

11–14 Reverting to his theme of impending judgment, the Lord instructs Ezekiel to demonstrate joy because of the coming judgment. Clapping the hands and stamping the feet signify either joyful praise or derision over sin and judgment (21:14–17; 22:13; 25:6; cf. La 2:15; Na 3:19). Ezekiel exhibits God’s delight over the comprehensive eradication of pagan shrines and practices from the land. The entire land would become as desolate as the desert toward Diblah. Everyone would be touched by the judgment: the distant ones by disease, the near ones by the sword, the remainder outside and inside Jerusalem by famine. Four times God directed Ezekiel to remind the exiles that the purpose for God’s judgment was to restore his hearers to an experiential knowledge of God (vv.7, 10, 13, 14). This major thrust of the book called for an intimate relationship with the Lord rather than a destructive allegiance to impotent idols.

In every generation God’s judgment and discipline are misunderstood by most people. God’s chief desire is to bring people to himself—or back to himself. When humankind willfully refuses to turn to him, God mercifully uses discipline and judgment to cause the people to recognize that he is the only true God, always faithful to what he has said in his word!

b. The imminency and comprehensiveness of the curse (7:1–13)

1–4 God now gives a second message to Ezekiel, containing four brief, intensive prophetic speeches in poetic form that emphasize the imminency and comprehensiveness of the coming judgment on all Judah. Numerous short sentences and the repetition of words and phrases express the intensity of the message. The recurrence of the word “end” (GK 7891) stresses the finality of the judgment. Judgment had come! Imminency was heightened by the reiteration of the verb “coming,” the repetition of “now,” and the use of terms like “time,” “day,” and “is near.”

The first prophetic speech (vv.1–4) emphasizes the extent—“the four corners of the land”—of the judgment and its basis; two main points summarize the reasons for judgment. Judah would be judged according to her wicked ways. Her abominations would be brought on her. The Exile would bring the Judeans into countries where the same abominable practices they had taken part in were a daily occurrence. The expectation was that this would cause them to detest such wicked rituals. Furthermore, the Lord would have pity on no one. He would not spare them. Though his forbearance and compassion had withheld discipline, such restraint would no longer continue. God’s judgment genuinely manifested his love, for its purpose was to cause Judah to know that he is God.

5–9 The second oracle emphasizes the horror and surprise of the judgment as well as the person of the judge. The terror that would fill the land is stressed by the repetition of the words “disaster” and “end,” in addition to the announcement that the judgment would be a time of panic, not joy like that experienced at harvest festivals (cf. Isa 16:10; Jer 25:30). The unexpectedness (chs. 12–19) of judgment is reflected by a play on words in “the end has come” and “roused itself,” as well as by phrases such as “Doom has come,” “time has come,” and “the day is near.” Verses 8–9 give the basis for the judgment stated in vv.3–4. The message closed by stunning the exiles with a new name for God: “The LORD who strikes the blow”—the one who would now judge Judah.

10–11 The third oracle focuses on the imminency, comprehensiveness, and readiness of judgment. The dawn of the judgment day had arrived; it had suddenly “budded” and “blossomed.” The “rod” is either Nebuchadnezzar as the instrument of judgment or the insolence of the kings of Israel. The only passage in Scripture referring to a “budded rod” is Nu 17, where God used such a rod to denote his choice. But since judgment on Judah is described here, it would seem best to understand the “rod” as an instrument of judgment that had been divinely chosen and was ready for use. The concept of the budding rod stands in parallelism with the previous line of the poem (indicating imminency) and the following line (describing the nature of the rod God would use to discipline Judah—a rod of “arrogance”). Nebuchadnezzar fits the description of this rod as an instrument of judgment. God would use this weapon to devastate the land until nothing of value was left.

12–13 The last oracle emphasizes the permanency and quickness of the judgment. Its suddenness is illustrated by the inability one had to regain what one had sold because of the rapidity of the coming discipline. Most likely this example was given with the law of the sabbatical year (Dt 15:1–2) or the Year of Jubilee in mind (Lev 25:13–16). According to that law, if one sold land to pay for a debt, that land reverted to him on the sabbatical year or the Year of Jubilee, whichever came first. Ezekiel maintained that if one sold land under this arrangement, he would not realize its return since neither he nor the buyer would be in the land of Judah seven years hence. Though the buyer might rejoice over the fact that he would never have to return the land, it would not be a time of rejoicing for either party. When judgment came, neither would own the property. Babylon would possess it!

The vision of judgment was certain! God would not repeal it! No one would be able to continue to live in iniquity, for all wickedness would be judged.

c. The response to the curse (7:14–27)

14–18 The last half of this chapter vividly describes the reactions of the Judeans to this swift and violent judgment. Moral dissipation, famine, and disease had so decimated the nation that they would be unable to muster an army when the trumpet sounded for battle. Therefore the Babylonians would easily approach Jerusalem for the siege (cf. Lev 26:7).

Disease and hunger would slay those within Jerusalem, and the sword would catch by surprise those working outside the walls. Any fortunate enough to escape the initial invasion would flee to the hills. There, shuddering in fear, weak and dismayed, they would be ashamed of and humiliated by their sins that brought this destruction. They would put on sackcloth in mourning, shave their heads in humiliation, and moan like doves.

19 Nothing could deliver the Israelites from God’s awesome wrath demonstrated in Jerusalem and Judah’s destruction in 586 B.C. Many of the inhabitants had lived for wealth so long that material gain had become an obsession to them. Yet in the judgment these riches would mean nothing. Idolatry, wickedness, and materialism had robbed them of everything and led them into judgment. Money would be thrown away like something sexually unclean.

20–22 Judah had profaned her sanctuary. The “beautiful jewelry” refers to Jerusalem and her temple; “my treasured place” likewise refers to the temple when connected with the full discussion of Jerusalem’s fall (see 24:21, 25). The people had taken ornaments and treasures from the temple and defiled God’s temple by using them to make idols. Ironically, God would now allow foreigners to profane the temple, plundering its treasures. Everything would become spoil for Babylon.

23–24 “Chains” were prepared to bind the captives for deportation to Babylonia. This was their due for the violent crimes they had committed. As the Judeans were leaving, the worst foreigners among the nations would enter and possess the land, profaning their holy places. The land would come under Babylonian dominion.

25–27 The last response for some was to seek help. People would run to the prophet in hope of a visionary revelation of deliverance, to the priest for messages from the law that might help, or to the elders for counsel in this time of distress. None could offer help. They had no answers at all! The leadership had failed in its responsibility to lead the people in God’s ways. It was too late! The anguish of judgment had come! If the people had sought peace earlier, it would have been available; but now there was no peace. Kings and princes would be horrified and mourn. God had judged Israel by her own judgments—by the Mosaic covenant they should have known and followed. The only redeeming factor was that they would learn that the Lord truly was God and that his covenants were to be obeyed!

B. The Vision of the Exodus of God’s Glory (8:1–11:25)

1. The idolatry of the house of Israel (8:1–18)

a. The image of jealousy (8:1–6)

1–6 Verse 1 describes the single vision of chs. 8–11. The date was “in the sixth year, in the sixth month on the fifth day” (August/ September), 592 B.C. The recipient was Ezekiel. He received the vision while sitting in his house with the elders of Judah sitting before him. God’s hand came on Ezekiel, causing him to be caught up into the vision. From the chronological notices of 1:1–3 and 8:1, it appears that he received his vision about fourteen months into his symbolic siege of Jerusalem. He was still lying daily on his right side, bearing the iniquity of Judah (cf. 4:6). Most likely the elders had been watching this performance, wondering whether anything new would happen. It was fitting for Ezekiel to be on his right side when this vision of Judah’s judgment appeared to him.

In light of the distance and time involved, these elders were not contemporary elders in Judah who had come from Judah to Babylonia to seek counsel from Ezekiel. Moreover, the depraved character of the Judean elders revealed in this vision would not have led them to take such an arduous journey to Babylonia for genuine spiritual reasons. Rather, the elders sitting before Ezekiel were the leaders of the Judean exiles in Babylonia who had already been deported from Judah in the captivities of Daniel (605 B.C.) and Jehoiachin (597 B.C.).

The vision’s primary thrust was to make known the cause of the coming judgment on Jerusalem. The political rulers, the prophets, and the priests were expected to lead Judah in her holy ways. In this vision Ezekiel saw the contrast between God’s glory in the sanctuary and the extreme moral and spiritual corruption of the nation’s leadership. The latter was the main cause for God’s judgment on Jerusalem. In ch. 8 the abominable idolatry as practiced by Judah’s leaders in the temple precinct was exposed. Chapters 9–11 depict the judgment of a holy God on the unholy perversion described in ch. 8. Progressively God’s glory is removed from Jerusalem and Judah. Appointed men are sent to pour out fiery judgment on this wicked idolatry and its proponents. The Judean leaders are singled out for special condemnation in 11:14–21, but the faithful remnant who repented of their sinful ways are marked for protection (9:4) and reassured of their ultimate restoration and cleansing (11:14–21).

The vision begins in vv.1–6 with Ezekiel seeing the same manifestation of God’s glory that he had seen on the river Kebar in chs. 1–3. In the vision of ch. 8, the likeness of a man of the same appearance as the one in the vision of ch. 1 (cf. 1:27) caught Ezekiel by his hair and transported him by the Spirit to Jerusalem in the vision. In Jerusalem Ezekiel saw God’s glory in the temple. Such glorious splendor stood in stark contrast to the religious perversion being practiced in the temple area.

Ezekiel found himself standing at the entrance of the inner court’s north gate, known also as the altar gate, because the altar of sacrifice was located just inside that gate (cf. Lev 1:11). He stood in the outer court at the gate’s entrance, not in the inner court. As he looked northward into the outer court, he saw the “idol of jealousy.” This idol provoked the Lord to jealousy, for he had declared in the Mosaic covenant that he alone was God (Ex 20:1–3) and that all idolatry was forbidden (Dt 4:16; 32:16, 21). The idol’s description is vague; thus it cannot be identified with certainty. Possibly it is a reestablishment of the idol of Asherah, the mother-goddess of the Canaanite pantheon, which Manasseh had erected in the temple (2Ki 21:7; 2Ch 33:7) but later removed (2Ch 33:15). This image certainly had its attraction in Israelite history, for Josiah had also had to remove it in his reformation (2Ki 23:6). Jeremiah’s denunciation of the worship of the Queen of Heaven may also relate to this image (Jer 7:18; 44:17–30).

The statement “But you will see things that are even more detestable” concludes this brief examination of the “idol of jealousy.” This conclusion emphasizes the progressive severity of Judah’s idolatry (vv.6, 13, 15).

b. Idol worship of the elders (8:7–13)

7–9 Ezekiel was brought into the north entry gate. There he saw a hole in the wall and was told to dig through the wall, enter, and observe what the elders of Israel were doing secretly in the inner court. These seventy elders were most likely the leaders of the nation who based their traditional position on Moses’ appointment of the seventy elders to assist him in governing God’s people (Ex 24:1, 9; Nu 11:16–25).

10–11 Jaazaniah, the son of Shaphan (possibly the son of Josiah’s secretary of state; see 2Ki 22:8–14; 2Ch 34:15–21; Jer 26:24; 29:3; et al.), was leading these men in burning incense to all sorts of sculptured animals, reptiles, and detestable things. Perhaps the detestable things were the animals declared unclean in Lev 11.

12–13 The Judean leaders were practicing their corrupt worship of these idols in the dark, each in his own room. These individual chambers are difficult to explain. Were they built into the wall that separated the inner and outer courts, or were they rooms in the private homes of each elder, indicating that each was engaged in this perverse ritual privately as well as publicly? Contextually, the former is preferable, though no such chambers were known to have existed within the inner court of Solomon’s temple.

These leaders rationalized their activities by declaring that God did not see them nor was he present anymore. He had forsaken the land, as demonstrated by the deportations of 605 B.C. and 597 B.C. They denied the existence of God in direct opposition to his name: “the one who always is.” They negated his omnipresence and omniscience, choosing to exchange “the glory of the immortal God for images made to look like . . . birds and animals and reptiles” (Ro 1:23). In saying that God had forsaken the land, the elders repudiated his faithfulness to the Abrahamic covenant, his love for his chosen people, and his immutability. With this kind of rationalization, they permitted themselves to do anything they desired. If God did not exist, then no one need care about him.

c. Tammuz worship of the women (8:14–15)

14–15 Leaving the inner court and the iniquity of the elders, Ezekiel returned to the entry way of the inner court’s north gate, where he observed women worshiping Tammuz, an ancient Akkadian deity, the husband and brother of Ishtar. Tammuz, later linked to Adonis and Aphrodite by name, was a god of fertility and rain, similar to Hadad and Baal. In the seasonal mythological cycle, he died early in the fall when vegetation withered. His revival, by the wailing of Ishtar, was marked by the buds of spring and the fertility of the land. Such renewal was encouraged and celebrated by licentious fertility festivals.

The date of this vision was in the months of August/September, when this god Tammuz “died.” At the time of this vision, the land of Palestine would have been parched from the summer sun, and the women would have been lamenting Tammuz’s death. They perhaps were also following the ritual of Ishtar, wailing for the revival of Tammuz. But there were still greater abominations for Ezekiel to see (cf. vv.6, 13).

d. Sun worship (8:16–18)

16 Ezekiel returned to the temple’s inner court, where he noticed twenty-five men with their backs to the temple, facing east in sun worship. The identity of these men is unsure. Possibly they were part of the seventy elders just mentioned. But it would seem strange that only a portion of the seventy would have been engaged in the sun worship. Moreover, since this was the inner court and only priests were permitted access into that court (2Ch 4:9; Joel 2:17), they may have been priests (though, to be sure, the seventy elders of Israel had just been seen practicing their idolatry within the inner court). The specific numbers of seventy (v.11) and twenty-five are probably given to aid in distinguishing the two groups. Therefore, it is more likely that these “twenty-five men” are priests. If so, the number twenty-five suggests that there was one representative of each of the twenty-four courses of the priests plus the high priest (cf. 1Ch 23). Regardless of their identity, sun worship was strictly forbidden by the Mosaic covenant (Dt 4:19); and both Hezekiah and Josiah had had to remove this pagan practice from Judah during their reigns (2Ki 23:5, 11; 2Ch 29:6–7).

17–18 These verses summarize this chapter of perverse idolatry by declaring that this wickedness of Judah’s leaders had allowed violence to fill the land. All this had repeatedly provoked God. They were even “putting the branch [GK 2367] to their nose.” This phrase is problematic. The word’s normal reading is “twig.” Possibly putting the twig to the nose was part of the ritual practice of sun worship, a concept that fits this context well. Regardless, the context implies that the act was offensive to God.

All these abominable, idolatrous rituals brought the wrath of a holy God. He would judge without compassion. He would refuse to listen to the people’s cries for mercy, even though they shouted with a very loud voice. Judgment would come! The remainder of the vision continues to emphasize that point.

2. Judgment on Jerusalem and the departure of God’s glory (9:1–11:23)

a. The man with the writing kit (9:1–4)

1–2 As Ezekiel stood in the temple’s inner courtyard, aghast by the abominations being practiced, the Lord announced the coming of the city’s executioners. Ezekiel saw them enter the “upper gate,” equivalent to the inner court’s north gate (cf. 2Ki 15:35; 2Ch 27:3; Jer 20:2; 36:10). Each executioner carried a lethal weapon in his hand. They gathered together and stood beside the bronze altar. Among them was a man clothed in linen and carrying a writing kit.

Ezekiel 8:18 provides a transition in the vision, where God announced judgment on Jerusalem. He would execute it through these seven men (six executioners and the man in linen). A holy and righteous God would not allow idolatry to rob him of his rightful place as Israel’s true God. The basis of the judgment was God’s glory and holiness as seen in the theophany of glory and the linen clothing of the man with the writing kit. Linen was often worn by divine messengers (cf. Da 10:5; Rev 15:6) and was used for priestly garments (Ex 28:42); thus linen portrays the purity and holiness of God. On the other hand, judgment was stressed by these men gathering at the bronze altar, the altar of sacrificial judgment, ready to execute their assigned task.

3 The glorious God prepared to delegate the execution of this judgment to these men as he arose from above the cherubim and proceeded to the temple’s threshold. Most likely God’s glory, envisioned in the man of 8:2, had separated from the cherubim throne-chariot in the vision and moved from the Most Holy Place (cf. 8:4) to the temple threshold. From there the picture of God’s departure from his people in preparation for judgment began. With judgment imminent, God’s glory could not be present over the ark of the covenant in the Most Holy Place or in the presence of the divine Judge. Therefore, the Lord vividly demonstrated his readiness to judge the people by withdrawing his glory from the Most Holy Place to the entry of the temple, in order to assign the tasks of judgment.

4 The Lord commanded the man clothed with linen and carrying the scribal implements to go throughout Jerusalem and mark everyone who had genuine remorse and concern for the sins of the city, who saw that the heathen ways of Jerusalem were contrary to the Mosaic covenant, and who desired to see that covenant properly instituted in the city. This man marked them on their forehead with a mark of protection as the impending judgment drew near (cf. Rev 7:3; 9:4; 14:1). These people had a righteous heart attitude.

b. The executioners’ judgment (9:5–8)

5–7 God commanded the six men to follow the man with the scribal kit throughout Jerusalem and to exercise individual judgment on everyone who did not have the mark of protection, regardless of sex or age. They were to spare none. They began with the seventy elders polluting the temple with their secret worship of sculptured animals in the inner court. Judgment started in the temple (cf. 1Pe 4:17), the center from which religious leadership should come. However, Judah’s leadership had become corrupt. Therefore, the temple courtyards would be defiled by the blood of these worshipers of heathen deities (cf. Nu 19:11; 2Ki 23:16).

8 As Ezekiel found himself the only inner-court survivor of the judgment, he became alarmed at the mass of people destroyed by these executioners. Although he could appear hard, his heart throbbed with love for God and his people. He pleaded with God not to eradicate the entire remnant of Judah. She was the only tribe left, and some of that tribe had gone into exile to Babylonia already (605 B.C. and 597 B.C.). The present judgment, illustrated by these six men, looked as if it would consume the remainder of Judah.

c. Vindication of God’s judgment (9:9–11)

9–10 The Lord’s response to Ezekiel’s concern for the nation was to remind him that the iniquity of Judah was extremely great. Violence and spiritual perversion had filled the land because the people had forgotten God’s character, assuming that he did not see what they were doing because he had deserted them. They denied God’s omniscience, omnipresence, and faithfulness. The Lord had not left, because he presently was judging Judah for her iniquity and would not spare anyone. He did know the wickedness of the people, for he would recompense them for it.

11 As an encouragement to Ezekiel that all Judah had not strayed from God, the man with the writing kit reported, “I have done as you commanded.” In other words, the righteous ones had been marked.

d. Coals of fire on Jerusalem (10:1–7)

1–2 God instructed the man clothed in linen to take fire coals from the center of the cherubim chariot (cf. ch. 1) and to pour them out in judgment on the city to purify it (cf. Isa 6).

4–5 This parenthesis clarifies the setting. The cherubim throne-chariot was in the inner courtyard to the south of the temple. The temple precinct had been cleansed by the six men, and God’s glory had moved to the temple door. From there it filled the temple and the courts.

6–7 The man in linen faithfully responded to the Lord’s command to take coals from the cherubim. The cherub was probably the living being with a face like a “cherub.” He handed the live coals to the man in linen.

e. Cherubim and Ichabod (10:8–22)

8–17, 20–22 The living beings of ch. 1 are identified as “cherubim” (GK 4131) in this passage. Cherubim appear elsewhere in the Scriptures, though they were new to the discussion in Ezekiel. In the ancient Near East, a winged sphinx with a human head and a lion’s or bull’s body was often identified as a “cherub.” The OT cherubim are primarily represented as guardians and protectors (cf. Ge 3:24), though they also performed worship on the mercy seat of the ark of the covenant (Ex 25:18–20). Perhaps as a throne-chariot (cf. 1Sa 4:4; 2Sa 6:2; 2Ki 19:15; 1Ch 13:6; 1Ch 28:18; Pss 18:10; 80:1; 99:1), they were protectors and guardians of God’s glory.

18–19 A principal theme in this vision and in the book of Ezekiel is the departure and return of God’s glory. It departed from the temple because of the corruption within Jerusalem and Judah, but it would return in the end time when the nation had been fully cleansed (cf. 43:1–9). The gradual departure of God’s glory began in 9:3 and 10:4, when the glory of God left the Most Holy Place and moved to the temple’s entrance. God’s glory departed from the temple’s threshold and assumed its place on the cherubim throne-chariot. Together they went to the temple’s east gate, from where they finally departed (cf. 11:22–23). Scripture declares (Dt 31:17; Hos 9:12) that this departure would occur if the people strayed from God’s ways. In 1Sa 4 a similar example of the departure of God’s glory at a time of judgment was memorialized by the name of Eli’s grandson “Ichabod” (v.21), which means “inglorious.” Once again, in Ezekiel’s day God was writing “Ichabod” over Jerusalem and Judah.

f. Judgment on Jerusalem’s leaders (11:1–13)

1 As Ezekiel watched God’s glory move to the east gate of the temple complex, the Spirit brought him to that gate. Here God showed Ezekiel more of the perversion of the nation’s leadership. Twenty-five men were gathered together, led by Jaazaniah, the son of Azzur, and Pelatiah, the son of Benaiah, leaders of the people (these twenty-five political leaders were different from the twenty-five sun worshipers of 8:16).

2–3 These leaders had given the people false and evil counsel. They had planned evil things, deceiving the inhabitants of Jerusalem and Judah by encouraging them to build homes at a time when the prophets were continually warning of the impending Babylonian destruction. These leaders were complacent and apathetic, believing that there was no imminent danger. They declared that Jerusalem’s inhabitants were secure inside Jerusalem’s walls by promulgating the proverb: “This city is a cooking pot, and we are the meat.” Jerusalem, “the pot,” provided security to its inhabitants, “the meat,” just as a pot protects the meat within it. Prophets like Ezekiel were declared to be misguided men using scare tactics.

4–6 Ezekiel prophesies to these twenty-five men with a judgment oracle; the accusation is stated in vv.5–6 and the verdict in vv.7–12. He reminds these leaders that their actions were not hidden from God; he knew exactly what they were thinking, saying, and doing. He knew they had rejected the prophets’ warnings, exchanged the righteous statutes of the law for idolatry, and murdered the inhabitants of Jerusalem with their devious schemes.

7–12 The verdict was expressed in the same imagery as the people’s proverbial statements in v.3. The “pot” of Jerusalem would protect only the righteous whom these wicked leaders had already slain. These corrupt leaders and their followers would be brought outside the “pot” of Jerusalem and struck down by the dreaded sword of foreigners. Babylonia would execute this judgment, slaying the Judeans throughout the land (cf. 2Ki 25:18–21). With the fall of Jerusalem to Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C., the Judean leaders and their subjects would know that the Lord was truly the Lord. They would observe that he faithfully executed the righteous judgment he had declared would come on those who failed to live according to his statutes. If Israel would obey, she would live (Lev 18:5). But she had chosen rather to live by the idolatrous ways of the nations around her and to receive the law’s curse instead of its blessing.

13 While Ezekiel was prophesying this message to the leaders, Pelatiah died. He did not actually hear Ezekiel’s prophecy, but news of Pelatiah’s death helped confirm Ezekiel as a prophet. This stunning result of his prophecy caused Ezekiel to fear once again that God would destroy all the remnant of Israel.

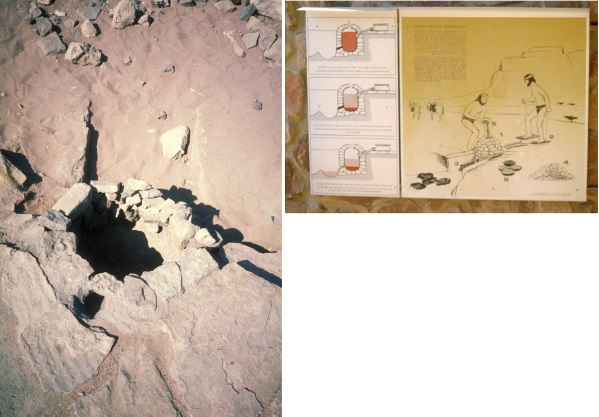

Large cooking pots, some of them completely intact, are often found while excavating biblical sites.

g. The future of the remnant (11:14–21)

14–15 Ezekiel’s great concern for the remnant of Judah had not gone unnoticed by the Lord. God encouraged him in this message that he and a remnant, his kindred, were purposely being kept by God through the Captivity. The citizens of Judah had looked on the exiles as the unclean and sinful part of the nation. Was not God judging them by their deportation? The Judeans encouraged the exiles to get as far away from the land of Israel as possible, because God had given it to those still in Judah, not to the sinful exiles.

16–20 On the contrary, God now shows that it was the deported remnant that he cared for; and he shows his care by promising to regather the exiles to the Promised Land. This is the first mention of a future restoration in Ezekiel. Many of the prophets held out restoration as a continual hope to the righteous. On the basis of the Mosaic covenant, judgment was all the prophets could offer Judah for her sins. The promise of restoration to the land, though declared in the blessings of the Mosaic covenant (Lev 26:40–45; Dt 30:1–10), was based on the eternal covenants to Abraham (Ge 12:1–3), David (2Sa 7:12–16), and Jeremiah (Jer 31:31–34).

In exile the Lord would continue to be an ever-present sanctuary for his people, making provisions for them no matter where they were scattered. This is the same ever-present God who today meets the needs of those who trust him, regardless of their circumstances. God then promises that when he finished disciplining the remnant of Israel, he would (1) regather them, (2) restore them to the land of Israel, (3) cleanse the land of its abominations, and (4) fulfill the new covenant with them.

The new covenant promised in Jer 31:31–34 provided for a change of heart and a new spirit. This new spirit would be the outpouring of the Spirit promised by the prophets (Dt 30:6; Jer 31:33; Joel 2:28–29), further developed in Eze 36:26–27, and initially instituted in Ac 2. The new heart and spirit would replace Israel’s old heart of stone (Zec 7:12), which had become so hardened against the Lord and his ways. The people would be empowered to live in the godly manner set forth in the stipulations of the Mosaic covenant. Finally they would truly reflect the Mosaic covenant formula: they would be God’s people, and he would be their God.

Through his death for sin once for all, Christ, the Mediator of the new covenant (Heb 8:6), has made it possible for all believers to receive the Spirit’s divine enablement so that they too may live according to God’s righteous standards. This is available to all who place their faith in the resurrected Messiah, Jesus Christ.