INTRODUCTION

1. Purpose

The book of Daniel was written in the context of the Fall of Jerusalem and the deportation of the Jews to Babylonia. Despite decades of warning by numerous prophets, the people’s flagrant apostasy and immorality finally brought to pass the destruction God had warned them about ever since the time of Moses (Dt 28:64; 29:28; 2Ch 36:16).

From a human viewpoint, it now seemed that the religion of the Hebrews had been completely discredited. The Lord appeared inferior to the gods of Assyria and Babylon. It was therefore essential at this time in Israel’s history for God to display his power in such a way as to prove that he was the one true God and the sovereign Lord of history. So by a series of miracles he vindicated his position as the only true God over against his detractors and convinced the supreme rulers of Babylon and Persia that he, the Lord, was the greatest power both on earth and in heaven.

2. Authorship and Date

Many today deny that the prophet Daniel wrote this book, particularly the last six chapters. The most common argument is that the remarkably accurate “predictions” in Daniel (esp. ch. 11) were the result of a pious fraud, perpetrated by some zealous propagandist of the Maccabean movement, who wished to encourage a spirit of heroism among the Jewish patriots resisting Antiochus IV. Many modern scholars claim that every accurate prediction in Daniel was written after it had already been fulfilled, i.e., in the period of the Maccabean revolt (168–65 B.C.).

The clear testimony of the book itself, however, is that Daniel was the author (cf. 8:1; 9:2, 20; 10:2). Nor is there any question that Jesus also accepted Daniel as the author of this book (Mt 24:15; cf. Da 9:27 et al.). Furthermore, careful linguistic and historical analysis of the book supports a date much earlier than the second century B.C.

As to the date of the composition of Daniel, the first chapter refers to Daniel’s capture in 605 B.C., and Daniel continued his public service until the first year of Cyrus (1:21), i.e., about 537 B.C. Daniel probably completed his memoirs c. 532 B.C., when he was about ninety years old. The appearance of Persian-derived governmental terms in Daniel strongly suggests that it was given its final form after Persian had become the official language of the government. Actually, the text of Daniel is in two languages: Hebrew (chs. 1, 8–12) and Aramaic (chs. 2–7). The Aramaic chapters pertain to the Babylonian and Persian empires, whereas the other six chapters relate to God’s special plans for his covenant people.

3. Canonicity

Daniel should be regarded as having been inherently canonical from the very time it was first written and as having achieved recognition by God’s people as the inspired word of God quite soon after its publication. It certainly would have found a ready reception among the exiles who returned to Judea under Zerubbabel because of its encouragement for them to trust in God’s continuing providence in their behalf during the discouragements of those early years of recolonization. The discovery of several fragments of a second-century MS of Daniel in Qumran Cave I indicates that Jewish believers considered the book as inspired and authoritative.

4. Theological Values

The principal theological emphasis in Daniel is the absolute sovereignty of the Lord, the God of Israel. The book consistently emphasizes that the fortunes of kings and the affairs of humans are subject to God’s decrees, and that he is able to accomplish his will despite the most determined opposition of the mightiest potentates on earth. The miracles recorded in chs. 1–6 clearly demonstrate God’s sovereignty on behalf of his saints.

A second theological emphasis is the power of persistent prayer. Daniel and his companions were delivered from dangers and dilemmas by prayer. Especially impressive is Daniel’s intense prayer on behalf of his nation for God to restore his people to their land at the end of the seventy years (9:2–19; cf. 10:12–14).

Another theological emphasis is the long-range purview of God’s marvelous plan of the ages. Daniel predicts the precise year of Christ’s appearance and the beginning of his ministry in A.D. 27 (cf. Da 9:25–26). Daniel was given the revelation of the eschatological Seventieth Week (9:26b–27), a week that we still eagerly look forward to.

Lastly, underlying the entire scenario is the indomitable grace of God. Even after the sternest warnings of the prophets had been disregarded and severe judgment of near total destruction had overtaken the nation in 587 B.C., the Lord never abandoned his people to the full consequences of their sin but in lovingkindness subjected them to an ordeal that purged them of idolatry. Then he allowed them to return to their homeland, thus setting the stage for the coming of the Messiah. The book of Daniel thus sets forth the pattern of God’s persevering grace that characterizes the NT as well, that “God’s gifts and his call are irrevocable” (Ro 11:29).

EXPOSITION

I. The Selection and Preparation of God’s Special Servants (1:1–21)

1–2 Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, first invaded Palestine in 605 B.C. and took captives back to Babylon. His second invasion was in 597 B.C. (cf. 2Ki 24:10–14). The third and final captivity took place in 587 B.C., when all the remaining people of Judah who had not escaped were taken to Babylon (for the significance of these dates, see the comments on ch. 9).

The first (i.e., 605) invasion was in the “third” year of the reign of Jehoiakim; this follows the Babylonian method of designating the years of a king’s reign. According to the Jewish method of counting those years, 605 B.C. was his fourth regnal year (Jer 25:1). Jehoiakim began his reign in 608, as an appointee of Neco king of Egypt, who officially changed his name from Eliakim (“El will establish”) to Jehoiakim (“Yahweh will establish”).

From the very beginning of this book, Daniel makes it clear that Nebuchadnezzar’s success was not due to his own prowess but was the work of the one true God, who had brought about the complete collapse of the Judean monarchy. Thus the theme of God’s absolute sovereignty is implied already here, a theme that dominates the entire book.

3–7 Nebuchadnezzar enlisted the most promising and gifted young men from Judah into his service, all of whom were assigned new names that contained the names of false gods of Babylon. A court official named Ashpenaz was put in charge of their physical and intellectual development. They were expected to follow the demanding course of study (cf. v.4) of the Chaldean curriculum.

Four of the Jewish youths accepted in the academy are singled out as having the courage to object to the food prepared for them and desiring to observe the dietary laws of the Torah (cf. Lev 11; Dt 14). Probably most of the meat items on the regular menu were from animals sacrificed to the gods of Babylon, and no doubt the wine from the king’s table had first been part of the libation to these deities. Therefore even those portions of food and drink not inherently unclean had been tainted by contact with pagan cultic usage.

At the very beginning of their careers, therefore, these young worshipers faced a clear-cut issue of obedience and faith. Had they complied with their rulers, they would have displeased God, to whom they were surrendered body and soul. This early refusal to disobey God prepared them for future greatness as true witnesses for him in this pagan culture.

8–16 Daniel, spokesman for the four young Hebrews, determined to refuse the food from the king’s table. Rather than break faith with God, he was willing to be expelled from the royal academy with the disgrace and danger that entailed.

But Daniel found “favor” (lit., “love or loyalty based on a mutual commitment”; GK 2876) with Ashpenaz and felt he could confide in him. Daniel proposed that the four Hebrews be given “vegetables” (“herbs” or “garden plants”) to eat and “water to drink” and that Ashpenaz see whether after a ten-day testing period all four of them did not look healthier than any of the other students. Such reversal of the laws of nutrition would require a miracle; yet Ashpenaz was willing to take the risk. The venture proved completely successful. No further objection could be raised against their simple diet.

17 Daniel and his friends were granted special wisdom by the Lord, not because of their diet, but because of his approval of their faith and commitment to his word. Daniel even mastered oneiromancy (the interpretation of dreams; cf. Joseph in the court of Egypt).

18–20 Ashpenaz proudly presented his students before Nebuchadnezzar for the final examinations. Out of the entire group of brilliant young men, the king found that the four Hebrews excelled vastly; so he gave them responsible posts in his government. “Magicians” (GK 3033) probably were those who used a chart or design to answer questions. “Enchanters” (GK 879) is derived from the Akkadian word for “soothsayer.” The text does not state that the four Hebrews actually engaged in divination or conjuration (cf. Dt 18:10–12) but that they attained “wisdom and understanding,” which implies that they surpassed the professional heathen diviners and conjurers. (Nowhere is there any indication that Daniel resorted to occult practices. He simply went to God in prayer, and God revealed the answer to him.)

21 Daniel’s career in public service continued “until the first year of King Cyrus.” Since Babylon was at first entrusted to Darius the Mede by King Cyrus (Da 5:31) after its fall in 539, and since Da 9 is dated in the “first year” of that Darius (9:1), Darius possibly remained as titular king till 538 or 537. If so, the “first year” of Cyrus king of Babylon would have been 537–536 B.C., which was probably the year when the forty-two thousand Jews returned to Palestine under Zerubbabel. If Daniel studied in the royal academy for three years, his first government appointment might have been around 601 B.C. Thus his whole term of service would have been about sixty-five years (601–536 B.C.).

II. Nebuchadnezzar’s First Dream: God’s Plan for the Ages (2:1–49)

A. The Babylonian Wise Men’s Impotence (2:1–13)

1–3 Nebuchadnezzar was convinced that his remarkable dream contained a message of utmost importance. He ordered his experts in oneiromancy to reconstruct the dream itself and then to tell him its significance.

In addition to the magicians or diviners and the enchanters or conjurers, “sorcerers” (GK 4175) are mentioned, along with “astrologers.” The word for “to practice sorcery” (or witchcraft) comes from Akkadian and strongly suggests necromancy as the original idea. “Astrologers” (GK 4169) translates a Sumerian term that is applied to a special class of astrologer-soothsayers. This fourth class of wise men acted as spokesmen for the whole group.

4–9 Verse 4 marks a transition from Hebrew to Aramaic in the text of Daniel, prefaced by the statement that the wise men spoke Aramaic with the king (see Introduction).

“O king, live forever!” represents a wish that the king would live on from one age to another (cf. 1Ki 1:31). The soothsayers’ request for the king to reveal his dream to them was met with a surprising rejection. He wanted them to give its contents and then to explain the meaning. If they really had powers of divination, their gods would be able to pass the dream on to them. This would prove that they were not giving a purely human and essentially worthless conjecture as to the interpretation.

To his stringent demand, Nebuchadnezzar added a gruesome threat. Failure to reconstruct his dream would prove that the wise men were charlatans who deserved death for all the years they had deceived the king. They would be “cut to pieces” (cf. Eze 16:40; 23:47) and their estates utterly destroyed and left as refuse heaps. But if they should succeed, Nebuchadnezzar promised them wealth and honor far beyond what they already had. The “wise men” were powerless before the threats of punishment and the inducements of reward. They could only beg the king to change his mind and divulge his dream. This enraged him further as he accused them of stalling for time to find a way out of their dilemma. But no deception would help them, nor could they look for any unexpected turn of events to extricate them.

10–13 In desperation the wise men insisted that the king’s demand was unreasonable, unprecedented, and beyond mortal ability. This defense convinced the king that his wise men were liars and deserved the penalty he had announced. So he issued a warrant for the arrest and execution of all the wise men (v.1), including the four young Hebrews.

B. Daniel’s Intercession and Offer (2:14–23)

14–16 Arioch, the captain of the royal bodyguard, told Daniel why all the wise men had been condemned. At Daniel’s request Arioch took him to Nebuchadnezzar to secure a stay of execution until Daniel had an opportunity to consult his God about the mysterious dream. The stage was set to show the reality, wisdom, and power of the one true God—the Lord of Israel. Daniel knew that he had to trust in God’s faithfulness to do the impossible. If he succeeded, Nebuchadnezzar and all Babylon would be confronted with irrefutable proof that only Israel’s God was real, sovereign, and limitless in his power.

17–23 Daniel, confident that God would answer his prayer, sought to make his prayer even more effective by enlisting his three companions in a concert of prayer. Verses 20–23 are a ringing manifesto of biblical faith over against the pretensions of pagan pride. Although the Babylonians may have triumphed on earth, the God of Israel was absolute Sovereign in heaven and on earth. His power is illustrated by his complete control over the events of history, bringing about the reversals of fortune that give history its unpredictability. God determines the time and duration of events. Thus he not only decreed the Fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.—an event future for Daniel in 602 B.C.—but also the exact number of years of the Captivity (cf. 9:2).

Daniel acknowledged that God alone bestows wisdom and discernment (v.21b). Only by his grace are humans able to achieve anything or to understand the “deep and hidden things” or what “lies in darkness.” Thus, all the knowledge of Nebuchadnezzar’s wise men could not give the king his dream and deliver them from imminent death.

Daniel closed his thanksgiving on a joyous note, expressing his confidence that the knowledge he had received of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream was absolutely accurate. Acknowledging that the superhuman “wisdom” and “power” he was about to display as the interpreter of the king’s dream had been granted in response to the collective prayers of him and his four companions, Daniel gave God all the glory.

C. Daniel’s Recitation of the King’s Dream (2:24–35)

24–25 Daniel assured Arioch, who was to execute the wise men, that he had the answer. Arioch, anxious to claim credit for himself in having discovered Daniel, hurried to tell Nebuchadnezzar his good news.

26–30 Capitalizing on Nebuchadnezzar’s half-incredulous inquiry as to whether Daniel could actually describe his dream, Daniel pointed to the pagan seers’ inability to unravel the mystery, thereby exposing the worthlessness of their theology and of polytheism in general. That the Lord’s spokesman alone had the answer points unmistakably to the reality of the God of the Hebrews. Then Daniel told Nebuchadnezzar what he had seen in his dream.

First, Daniel reminded the king that preceding his dream, he was thinking about the future. Disclaiming any personal ability in transmitting this revelation and publicly giving God all the glory, Daniel implied that God had noticed the king’s statesmanlike concern and had granted him a full answer to his thoughts on what was to come.

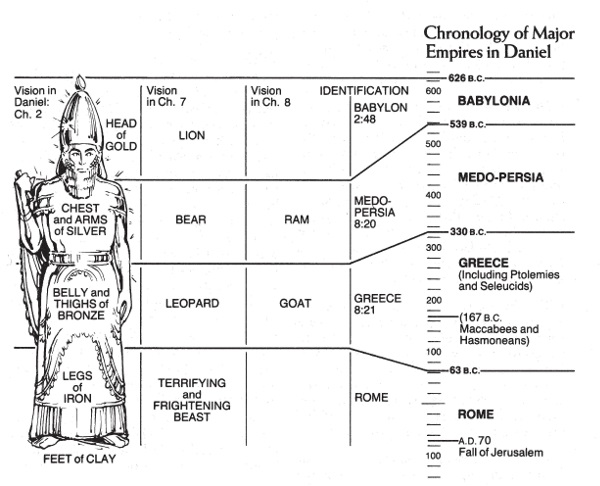

31–35 Daniel disclosed the main theme of the dream—the colossal image composed of a head of gold, breast and arms of silver, belly and thighs of bronze, and legs of iron, with feet of iron mingled with clay. This composite statue was then reduced to powder by a huge stone, and the powder was blown away by the wind. Where the image had stood, the rock grew to the size of a huge mountain that filled the whole scene.

D. Daniel’s Interpretation of the King’s Dream (2:36–47)

36–38 The golden head represented Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonian Empire. The head came first in the explanation probably because “head” often means “beginning.” To Nebuchadnezzar, his government was the ideal type and was therefore esteemed as highly as gold. He exercised unrestricted authority throughout Babylon. His word was law.

The first world-empire, then, was the Neo-Babylonian, over which Nebuchadnezzar ruled for about forty more years—from 605 to 562 or 560 B.C. But his empire did not last more than twenty-one years after his death. His son Evil-Merodach reigned only two years (562–560). Neriglissar reigned four years (560–556) and Labashi-Marduk only one (556). Nabonidus engineered a coup d’etat in 555 and ruled till Babylon fell in 539.

39 The second empire (silver) is said to be “inferior” to Babylon. From Nebuchadnezzar’s standpoint the restriction on the king’s authority to annul a law once he had made it (6:12) was less desirable than his own unfettered power. The silver empire was to be Medo-Persia, which began with Cyrus the Great, who conquered Babylon in 539 and died ten years later. His older son, Cambyses, conquered Egypt but died in 523 or 522. After a brief reign by an upstart claiming to be Cyrus’s younger son, Darius son of Hystaspes deposed and assassinated him and established a new dynasty. Darius brought the Persian Empire to its zenith of power but left unsettled the question of the Greeks in his western border, even though he did conquer Thrace. Xerxes (485–464) his son, in an abortive invasion in 480–479, failed to conquer the Greeks. Nor did his successor Artaxerxes I (464–424), who rather contented himself with intrigue by setting the Greek city-states against one another. Later Persian emperors—Darius II (423–404), Artaxerxes II (404–359), Artaxerxes III (359–338), Arses (338–336), and Darius III (336–31)—declined still further in power. This silver empire was supreme in the Near and Middle East for about two centuries.

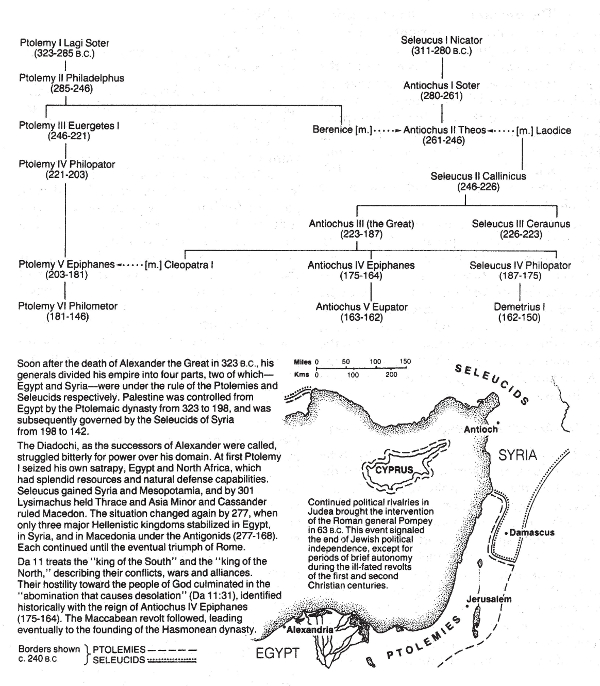

The third empire (bronze) was even less desirable from Nebuchadnezzar’s standpoint. This empire was the Greco-Macedonian Empire established by Alexander the Great. Though Greece was to “rule over the whole earth,” its political tradition was more republican than its predecessor. Alexander began his invasion of Persia in 334, crushed its last resistance in 331, and established a realm extending from the border of Yugoslavia to beyond the Indus Valley in India—the largest empire of ancient times. After his death in 323, Alexander’s territory was split into four realms, ruled over by his former generals (Antipater in Macedon-Greece, Lysimachus in Thrace-Asia Minor, Seleucus in Asia, and Ptolemy in Egypt, Cyrenaica, and Palestine). This situation crystallized after the Battle of Ipsus in 301, when the final attempt to maintain a unified empire was crushed through the defeat of the imperial regent Antigonus. The eastern sections of the Seleucid realm revolted from the central authority at Antioch and were gradually absorbed by the Parthians as far westward as Mesopotamia. But the remainder of the former Greek Empire was annexed by Rome after Antiochus the Great was defeated at Magnesia in 190 B.C. Macedon was annexed by Rome in 168, Greece was permanently subdued in 146, the Seleucid domains west of the Tigris were annexed by Pompey the Great in 63 B.C., and Egypt was reduced to a Roman province after the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Thus the bronze kingdom lasted about 260 or 300 years before it was supplanted by the fourth kingdom prefigured in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream-image.

40–43 The fourth empire is symbolized by the legs of iron. From a despotic standpoint, the Roman Republic was of far less value than gold, silver, or bronze. Iron connotes toughness and ruthlessness and describes the Roman Empire that reached its widest extent under the reign of Trajan (98–117 A.D.), who occupied Rumania and much of Assyria for a few brief years.

A later phase of the fourth empire is symbolized by the feet and ten toes made up of iron and clay, a fragile base for the huge monument. The implication is that this final phase would be marked by a kind of federation rather than by a powerful single realm. The iron may represent the influence of the old Roman culture and tradition and the clay the inherent weakness in a socialist society based on relativism in morality and philosophy. This mixture results in weakness and confusion, foreshadowing the approaching day of doom. Within the scope of v.43 are disunity, class struggle, and even civil war, resulting from the failure of a hopelessly divided society to achieve an integrated world-order. Iron and clay may coexist but cannot combine into a strong and durable world power.

44–45a The final scene is of a rock cut from a mountain that rolls down and smashes against the great image’s brittle feet (cf. v.34), toppling it over. The entire monument is then reduced to dust and swept away by the wind. Then the rock becomes a mountain (the fifth kingdom) that fills the earth. In contrast to the transitory nature of the four man-made empires, this God-established kingdom is destined to endure forever. Daniel 7 and parallel passages leave no doubt that this fifth realm is the kingdom ruled over by Christ.

45b–47 Daniel closed his interpretation of the dream by assuring Nebuchadnezzar that it was divinely inspired and absolutely trustworthy. Thus the God of heaven graciously granted the king knowledge of the future, unraveling the baffling mystery. The king could only respond by acknowledging Israel’s Lord as “God of gods” (i.e., the Supreme God) and “Lord of kings” on earth, the true Lord of history. Moreover, the king acknowledged the Lord’s supremacy in revealing the mysteries of the future, something no pagan god could do.

In token of his submission to Daniel’s God, Nebuchadnezzar prostrated himself before Daniel and gave him an offering and incense. What a remarkable scene! The despot who but an hour before had ordered the execution of all his wise men was prostrating himself before this foreign captive from a third-rate subject nation! The king’s praise to the Lord, however, does not necessarily mean that he doubted the existence of other gods, much less that he had experienced any sort of conversion.

E. The Promotion of Daniel and His Comrades (2:48–49)

48–49 As a result of Daniel’s outstanding performance, Nebuchadnezzar put him in charge of all the diviners. He officially became “ruler” (lit., “chief of appointed officials”; GK 10715) over the whole bureau of “wise men.” The king fulfilled his original promise (2:6) and loaded Daniel with gifts and honors, appointing him civil governor of the entire capital province of Babylon. Normally this would be reserved for a Chaldean nobleman of the master race. For a Jew to be so honored was unprecedented. Daniel requested that his three companions be given high appointments too, thus strengthening his position.

III. The Golden Image and the Fiery Furnace (3:1–30)

A. The Erection of the Image (3:1–3)

1–2 Nebuchadnezzar forgot his new religious insights and had a statue made of gold (i.e., covered with gold leaf; there was not enough gold in all Babylon to make a statue so large of solid gold), undoubtedly reflecting the head in the dream-image. It is doubtful that the statue represented the king himself as there is no evidence that statues of Mesopotamian rulers were ever worshiped during the ruler’s lifetime. More likely the statue represented Nebuchadnezzar’s patron god, Nebo (or Nabu). Prostration before this god would amount to a pledge of allegiance to his viceroy, Nebuchadnezzar. The recent establishment of the Babylonian Empire as successor to Assyria made it appropriate for Nebuchadnezzar to assemble all the leaders of his domain and exact from them an oath of loyalty, certified by a ceremony of adoration of Babylon’s god. Any who refused to comply were to be immediately executed in a superheated furnace.

3 The titles of the various ranks of government officials indicate a well-organized bureaucracy. “Satraps” were in charge of fairly large realms. “Prefects” were military commanders or more likely lieutenant governors. “Governors” were leaders of smaller territories. “Advisers” were “counsel-givers.” “Provincial official” is a general term for a governmental executive.

B. The Institution of State Religion (3:4–7)

4–7 Nebuchadnezzar enlisted the royal musicians to furnish a proper setting for the ceremony. “All kinds of music” indicates that there were other instruments besides the six listed. This orchestra would give the signal for all to bow down and worship the golden statue, declaring their commitment to the Babylonian government and their willingness to incur divine wrath if they should ever break their oath of fealty. The nearby furnace was a grim reminder of the dreadful alternative to compliance. When the music struck up, all foreheads touched the ground—except three.

C. The Accusation and Trial of God’s Faithful Witnesses (3:8–18)

8–12 After the public worship, some malicious men (called “Chaldeans” in the NIV note) reported to the king the disobedience of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. These informers approached the king as members of the master race, denouncing the Jews. This heightens their reference to Daniel’s three Hebrew associates in government service as “some Jews,” with a contemptuous emphasis on their despised nationality. With a show of zeal for the king, the Chaldeans quoted his edict word for word and then related how these three recalcitrant Jews had dared to “pay no attention to” the express command of “King Nebuchadnezzar”; they had refused to bow down and worship the golden image!

13–18 Nebuchadnezzar became furious and ordered the offenders to be brought before him. Half incredulously he stared at them and asked whether they really had disobeyed his decree. Then he magnanimously gave them an opportunity to save themselves. He would order the musicians to play again so the three men might prove their loyalty and obedience by worshiping the image then and there. But Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego loved the Lord more than life itself. Ready to lay down their lives for God’s glory, the three refused to plead with Nebuchadnezzar to make an exception of them. They were confident that the Lord would deal with this king who thought he was sovereign on earth.

Nebuchadnezzar made the mistake of defying the Lord, saying, “Then what god will be able to rescue you from my hand?” Nebuchadnezzar had converted his confrontation with humans into a contest with the Lord God Almighty. Ungratefully he scoffed at the very God who had granted him success in battle (cf. Jer 27:6–8). Therefore he would undergo one humiliation after another, till he groveled in the dust before Israel’s God.

The heroism of the three men went even further as they were ready to be burned up in the fiery furnace rather than betray their God. Scripture contains few more heroic words than “But even if he does not” (v.18). Interestingly, Scripture is silent as to Daniel’s whereabouts at this time. Perhaps he was away on official business.

D. The Sentence Imposed and Executed (3:19–23)

19–23 Nebuchadnezzar had no recourse but to order the immediate execution of the three young Hebrews. In his rage he went to absurd lengths. No mortal could have survived an instant in the huge furnace, but the king insisted that it be heated to maximum intensity. So fierce was the fire that even to come near it was fatal. Equally absurd was Nebuchadnezzar’s command for the three to be fully dressed with their hats on. Finally, they were “firmly tied” and thrown like logs into the furnace. Apparently there was no door to hide the inside from view. So apart from the swirling flames and smoke, the men were quite visible to an outside observer.

E. The Deliverance and the Fourth Man (3:24–27)

24–27 The dumbfounded Nebuchadnezzar saw the Hebrews walking upright in the flames without their bonds, and he saw a fourth person walking with them. After his officials confirmed that only three men had been thrown into the furnace, the king described the fourth one as resembling deity. All four persons in the furnace were walking around freely. Their divine companion in the flames had delivered Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from all harm.

Nebuchadnezzar commanded the three to come out of the furnace; so they climbed out—but not the fourth, who had apparently disappeared. To the officials’ amazement neither the clothing nor the bodies of the three Hebrews gave any indication of having been in the fire. Their God had indeed been able to deliver them (cf. v.17).

F. Nebuchadnezzar’s Second Submission to God (3:28–30)

28–30 Before such an awesome display of God’s power, Nebuchadnezzar could only acknowledge his defeat. He hastened to praise the Lord and thereby confess his admiration for the courage and fidelity of the three Hebrews. To make amends Nebuchadnezzar decreed death and destruction for anyone saying anything against the God of Israel. Then Nebuchadnezzar promoted Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego to a higher office in Babylon.

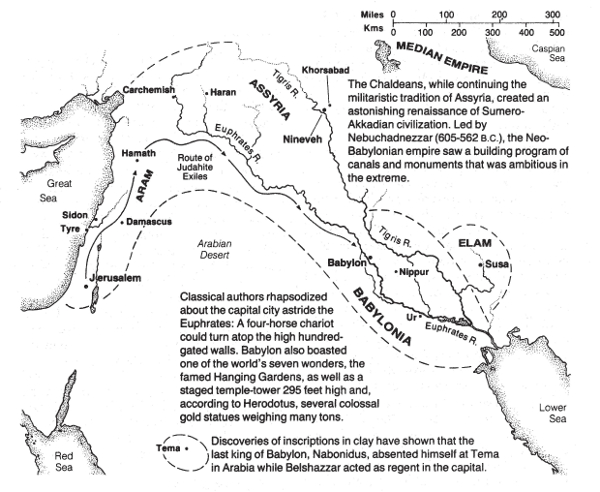

The Neo-Babylonian Empire 626–539 B.C.

© 1985 The Zondervan Corporation

IV. Nebuchadnezzar’s Second Dream and Humiliation (4:1–37)

A. The Circumstances of the Second Dream (4:1–7)

1–3 This chapter is unique in Scripture because it is composed under the authority of a pagan. Though he may have been intellectually convinced of the sovereignty and omniscience of the one true God, Nebuchadnezzar hardly had a true heart conversion. The decree showed his gratitude to the Lord for delivering him from insanity and restoring him to his throne. He wanted every person in his empire to share this knowledge and join him in giving glory to the God of heaven. Nebuchadnezzar frankly confessed his own arrogance in attributing to himself the glory for what the grace and power of God had done for him.

After blessing his subjects, Nebuchadnezzar exalted the miracle-working power and eternal sovereignty of the God of Israel. He made it clear that he had experienced this power both in his warning dream (explained by Daniel) and its pride-shattering fulfillment, his seven years of bestial insanity. These convinced him that God alone is the source of power, both in nature and in human affairs, and that no ruler possessed any authority except by God’s permission. In contrast to the transient reigns of human rulers, the authority of God goes on forever.

4–7 The setting for the following event is the apparent security and prosperity of the king after vanquishing all his enemies and the occasion of another dream. Again (cf. 2:2) the king sent for his wise men, although on this occasion he told them the substance of the dream (cf. ch. 2). When they could not come up with any interpretation, once more the king turned to the one true expert, Daniel the seer.

B. The Description of the Dream (4:8–18)

8 Daniel’s official court name is “Belteshazzar” (“Protect his life”), most likely an abbreviated form of Bel-belteshazzar (“Bel, protect his life”) or even Nebu-belteshazzar (“Nebo, protect his life,” if by “his god” the king was referring to the god whose name began his own, Nebu-chadnezzar). In contrast to the other soothsayers in his court, Nebuchadnezzar acknowledged that Daniel was truly inspired by God (or the gods).

9–18 The king told Daniel his dream about the great tree that grew to dominate the landscape for many miles and about its lush foliage and abundant fruit that provided shelter and nourishment for all sorts of creatures. Suddenly “a “holy one” (lit., “watchman”; GK 10620) descended from heaven and pronounced judgment on the tree, ordering it to be chopped down and its foliage stripped away. Verse 17 indicates that this particular class of angels can execute the judgments of God. The felling of the tree scattered the birds and beasts that were dependent on it. Only the stump was spared, and it was to be encircled with bands of iron and bronze and to remain in the grassy meadow (v.15a).

The symbolism changes from the stump to a man to a brute beast (vv.15b–16). “Mind” (GK 10381) refers to the inner self as the seat of moral reflection, the will, and pattern of behavior. The person this tree stump represents is to be transformed into an animal for seven “times,” here undoubtedly years (see NIV note; cf. 7:25). The sentence was decreed from heaven so that the full sovereignty of the “Most High” might be demonstrated before all the world, and that people might realize that God chooses who is to wear the crown and sometimes selects the humblest and lowliest (cf. 1Sa 2:7–8; Job 5:11). (For a prideful person portrayed as a lofty tree, see Isa 2:12–13; 10:34; Eze 31:3–17.) By appealing to Daniel, the king showed his confidence in him and his God. So once again the honor of Daniel’s God was at stake.

C. Daniel’s Interpretation and Warning (4:19–27)

19–22 Daniel’s loyalty to the king and his kindness to Daniel made it difficult to reveal the interpretation of the dream. At the king’s insistence Daniel finally began to speak. After voicing the fruitless wish that the dream might apply to Nebuchadnezzar’s worst enemies, Daniel explained that the mighty tree represented Nebuchadnezzar in all his military success, organizing an empire that stretched to the “distant parts of the earth.”

23–27 Daniel came to the heart of the warning: Nebuchadnezzar would lose both his power to rule and his sanity. He would be reduced to the mentality of a beast for seven years, eating grass like cattle. This humiliation would teach him to respect God’s sovereignty and to appreciate his glory and power.

Verse 26 closes with Daniel’s prediction about the surviving tree stump: after his seven years of dementia, Nebuchadnezzar will be restored to his throne. Normally any monarch suffering from insanity would be replaced. But the unlikely promise of God that the throne would he restored to Nebuchadnezzar after the termination of his insanity was fulfilled. The prospect of seven years of insanity was terrible; so Daniel closed with an earnest admonition for Nebuchadnezzar to defer the evil day by immediately amending his life. If he would recognize that he was subject to God’s moral law and responsible to him for good government, the discipline might be deferred. Nothing is said about Nebuchadnezzar’s response, but the one-year delay implies that he made some effort to follow Daniel’s recommendation.

D. The King’s Punishment (4:28–33)

28–30 Though eager to avoid judgment, Nebuchadnezzar nevertheless retained his pride, taking all the credit for the achievements he owed to God’s grace. Perhaps he refrained from boasting during his reprieve, but he never realized his indebtedness to God (see ZPEB, 4:395–99, for a description of Nebuchadnezzar’s accomplishments).

31–32 After boasting that he had built Babylon the Great as a residence for himself by his own power (v.30), Nebuchadnezzar heard an unexpected word from God—he would experience the full weight of God’s wrath and the punishment threatened in his fateful dream.

33 Nebuchadnezzar was abhorred even by his lowliest subjects and reduced to the state of a beast. His skin toughened into hide through constant exposure to the weather; his hair, matted and coarse, looked like eagle feathers; and his uncut fingernails and toenails became like claws. So the boasting king, a victim of a condition known as boanthropy, sank to a subhuman level.

E. The King’s Repentance (4:34–37)

34–35 After seven years the Lord fulfilled his promise. By divine grace the humiliated king’s reason returned. His first response was to praise, honor, and glorify God as the eternal, omnipotent Sovereign of the universe. Second, he honored him as the Ruler whose kingdom would never end. Third, Nebuchadnezzar acknowledged that humans are as nothing before God. Finally, Nebuchadnezzar saw that God is beyond the control of any human being and accountable to no one.

36–37 Now that he had begun to fear the Lord, Nebuchadnezzar was qualified for renewed leadership. The court and the army commanders were electrified to see that his reason had returned, and they thronged to congratulate him and hail him as their sovereign. “I was restored to my throne and became even greater than before” was his grateful testimony. The “head of gold” (2:38) had bowed in humble submission to the God of Daniel.

Through this event the Jews held captive in Babylon could not help but know that their Lord was the true and living God and that all the gods of the pagans were only idols. They knew for certain that the apparently limitless power of Nebuchadnezzar was under the control of the Lord God Almighty.

V. Belshazzar’s Feast (5:1–31)

A. The Profanation of the Holy Vessels (5:1–4)

(As background for this episode, see ZPEB, 1:446, 515–16.)

1–4 Belshazzar the king conducted a state banquet for his nobles. In drunken bravado he decided to entertain them with the vessels from the temple in Jerusalem. Belshazzar and his guests taunted the Lord by praising their gods and drinking from the sacred goblets. Once again an arrogant Babylonian monarch defied the Lord God of Israel.

B. The Handwriting on the Wall (5:5–9)

5–6 Divine intervention came without announcement. Suddenly fingers appeared on the palace wall, wrote four words, and vanished. The party was over. The drunken Belshazzar stared at the words, terrified.

7–9 The king sent for his wise men to unravel the message. They could come up with nothing, despite inducements of riches and position. (Belshazzar could offer nothing higher than the third highest rank in the government since he himself was a viceroy under his father, Nabonidus.) As in Nebuchadnezzar’s day, the wise men were baffled (cf. 2:2–11; 4:7).

C. The Queen Mother’s Recommendation (5:10–16)

10 Daniel (who was probably about eighty-one by 539 B.C.) was not included among those summoned. Perhaps he was in semiretirement, though ch. 8 indicates that he had been active as recently as the third year of Belshazzar (cf. v.1) but had not been enjoying good health (v.27). Evidently Belshazzar’s administration had set him aside though he lived in Babylon. But the king’s mother, likely a daughter of Nebuchadnezzar, thought of Daniel as soon as she saw the commotion in the banquet hall and urged the king to stop worrying.

11–12 The queen mother commended Daniel to the king, adding that Nebuchadnezzar had found him to be far superior to all the rest of his wise men (cf. 4:8), for Daniel could unravel mysteries and solve enigmas. Surely he was the right one for Belshazzar to consult. She referred to Nebuchadnezzar as Belshazzar’s “father.” Strictly speaking Nabonidus was his true father; but if Nabonidus had indeed married a daughter of Nebuchadnezzar to legitimize his usurpation of the throne, Nebuchadnezzar would have been Belshazzar’s grandfather.

13–16 Belshazzar sent for Daniel at once, apparently meeting him for the first time. He explained his concern and asked Daniel to explain the mysterious writing. The king also enumerated the same rewards—including the position of “third highest ruler”—he had offered the other wise men.

D. Daniel’s Interpretation (5:17–28)

17–24 Disclaiming all promotions, Daniel answered the king’s request. Studying the inscription on the wall, Daniel prefaced his interpretation with the reason for the judgment it contained. He reviewed the experience of Nebuchadnezzar being humbled by the decree of the Lord. The young king should have remembered what these experiences had taught his grandfather about humility and respect for the Lord. Belshazzar’s blasphemous conduct of profaning the Lord’s holy vessels in his drunken orgy had led to the handwriting on the wall, proclaiming Belshazzar’s doom.

25–28 Daniel then interpreted the four words. “Mene,” meaning “numbered” or “measured,” signified that the years of Belshazzar’s reign had reached their end. “Tekel” is related to the word for “shekel,” whose root idea is “to weigh.” In Belshazzar’s case, God found him deficient in his scales and therefore rejected him. “Peres” is derived from a root that means “to divide.” Belshazzar’s kingdom would be divided or separated from him and given to the Medes and Persians then besieging the city.

E. Daniel’s Honor and Belshazzar’s Demise (5:29–31)

29 Daniel’s interpretation greatly disturbed Belshazzar, for it was spelling his imminent doom. Perhaps hoping to forestall judgment, the king fulfilled his promises to the letter, bestowing the royal chain of gold on Daniel and proclaiming him the third ruler in the kingdom.

30–31 But the time for repentance had run out. Belshazzar had gone too far in profaning the vessels of the temple. Destruction was closing in on Belshazzar and his kingdom even while Daniel’s investiture was taking place. The Medo-Persian troops were moving along the exposed riverbed under cover of darkness and climbing the walls of the defenses throughout the city.

Verse 30 tersely reports that Belshazzar was slain that same night. The government of Babylon was then entrusted to Darius the Mede at the age of sixty-two. Thus was fulfilled Daniel’s prediction that the Babylonian Empire would pass under the yoke of the Medo-Persian Empire, as kingdom number two in the four-kingdom series. (For the identity of Darius and further background to this chapter, see ZPEB, 2:26–29; cf. also EBC 7, in loc.)

VI. Daniel and the Lions’ Den (6:1–28)

A. The Conspiracy Against Daniel (6:1–9)

1–3 One of Darius’s first responsibilities was to appoint administrators over the territory won from the Babylonians. The 120 “satraps” must have been in charge of the smaller subdivisions. Over these 120 were three commissioners, of whom Daniel was chairman. Daniel’s long experience and wide acquaintance with Babylonian government, combined with his superhuman knowledge and skill, made him a likely choice for prime minister.

4 Daniel encountered hostility in the new Persian government, no doubt because his enemies were race-conscious and did not appreciate the elevation of a Jewish captive. To be sure, King Cyrus was either looking favorably on the request of the Jews for release or had already promulgated the decree cited in Ezr 1:1–4. Though objects of Cyrus’s charity, the Jews were nevertheless considered inferior, especially by their conquerors. Daniel’s elevation to prime minister so disturbed his subordinates that they scrutinized his affairs, hoping to find something that marred his past. But their investigations proved fruitless; Daniel’s integrity was beyond question.

5 The way to get Daniel was to force him to choose between obedience to his God and obedience to the government. A statute was needed that seemed merely political to Darius but was clearly religious for Daniel. So his enemies proposed that for one month all petitions be directed to Darius alone. This flattered him and also served to impress the captives that they were now under the Persians.

6–9 The government overseers came to the king “as a group” (i.e., an official delegation) to present their proposal, falsely implying that Daniel concurred with them. Darius had no reason to suspect that the other two royal administrators would misrepresent Daniel’s position in this matter. The suggested mode of compelling every subject in the former Babylonian domain to acknowledge the authority of Persia seemed a statesmanlike measure that would contribute to the unification of the kingdom. The time limit of one month seemed reasonable. So Darius affirmed the decree.

B. Daniel’s Detection, Trial, and Sentence (6:10–17)

10 The new ordinance mandated death by caged lions for noncompliance (v.12). When Daniel received notice of this new law, he faced a dilemma. Prayer and fellowship with the Lord had safeguarded him from the corrupting influences of Babylonian culture. To preserve his role in government and to save his own life, he would have to compromise his integrity by ceasing to pray to God or by praying privately. But faithful Daniel could not compromise. He would trust the Lord for deliverance. His habit had been to pray regularly toward Jerusalem, the focal point of his hopes and prayers for the progress of the kingdom of God. (Ch. 9 reveals Daniel’s concern for Jerusalem and the Jews’ restoration to their land.)

11–14 Apparently in collusion in order to make a public test case of Daniel, the hostile officials waited for him to pray and then burst in on him, catching him violating the new decree. They lost no time in reporting Daniel to Darius, reminding him that he had forbidden all petitions to anyone but himself during the thirty-day period. Darius acknowledged that the decree was still in force and that the “laws of the Medes and Persians” could neither be changed nor revoked. In reporting Daniel’s disobedience to the king, the conspirators represented Daniel’s praying thrice daily as willful disrespect to his king rather than as devotion to his God. Darius’s response was not what the conspirators had expected. Indeed, he “was greatly distressed,” probably realizing that he had been manipulated by Daniel’s enemies. Throughout the day he tried his best to save Daniel’s life.

15–17 By sunset the king resigned himself to comply with the conspirators’ desire when they reminded him of his irrevocable decree. Concerned for his cherished minister, Darius went with Daniel to the lion pit. Before it was closed, Darius called down to Daniel, “May your God, whom you serve continually, rescue you!” For Darius these words voiced a tremulous hope (cf. v.20). A heavy stone was placed over the pit and secured with clay tablets bearing the king’s royal seal and that of other officials.

C. Daniel’s Deliverance and His Foes’ Punishment (6:18–24)

18–24 Darius was a troubled man. Daniel’s peril precluded the king from eating and entertainment. His anxious thoughts kept him awake till the first gray light of dawn, when he hastened to the lion pit, which was already unsealed. Darius’s apprehensive call stressed his hope that the “living” God whom Daniel served had “been able to rescue [him] from the lions.” Daniel’s voice from the bottom of the pit, relating how God had sent his angel to shut the lions’ mouths and to prove him guiltless, brought great joy to Darius. Not a scratch was found on Daniel. The evidence was incontrovertible—Daniel’s God had “stopped the mouths of lions” (Heb 11:33).

Daniel’s accusers were guilty of devising a decree to deprive the king of his most able counselor and of lying to the king when they had averred that “all agreed” (v.7) to recommend this decree. Therefore Darius ordered Daniel’s accusers to be brought before him; he then cast them with their families into the same pit. The fate of the conspirators and their families is a masterly touch of poetic justice: “And before they reached the floor of the den, the lions overpowered them and crushed all their bones.” Perhaps Darius consigned the families to death to minimize the danger of revenge against the executioner. Daniel’s position as prime minister was now secure.

D. Darius’s Testimony to God’s Sovereignty (6:25–28)

25–27 Darius made a public proclamation giving glory to the God of the Hebrews, commanding all citizens of the realm to honor him. The sense of vv.26–27 is like the last clause of 3:29—“no other god can save in this way”—and like 4:3. Three emphases stand out in vv.26–27: (1) Daniel’s God is alive and shows it by the way he acts in history, responding to the requirements of justice and the needs of his people; (2) God’s rule is eternal (unlike the empires built by mortals); (3) God miraculously delivers his people, with wonders in heaven and on earth. Once again God acted redemptively to strengthen his people’s faith in him.

28 The chapter ends on a positive note, highlighting Daniel’s continuing usefulness in royal service throughout the rest of the reign of Darius and in the reign of Cyrus (cf. 1:21). After this, Daniel apparently retired from public service and gave himself to the study of the Scriptures and to prayer. He received the revelations of chs. 10–12 in the third year of Cyrus (cf. 10:1).

VII. The Triumph of the Son of Man (7:1–28)

A. The Four Beasts and the Succession of Empires (7:1–8)

1 In the latter part of his career, Daniel received a series of visions and revelations. The revelation in this chapter is dated “in the first year of Belshazzar king of Babylon.” Nabonidus, his father, came to the throne in 556 B.C.; but he apparently entrusted to Belshazzar the “army and the kingship” of Babylon while he himself campaigned in north and central Arabia (so the Nabonidus Chronicle). It is uncertain whether the actual kingship of Babylon was immediately entrusted to Belshazzar at the commencement of his father’s reign or whether his appointment as viceroy came later, as Nabonidus found himself detained in Arabia.

Verse 1 says that Daniel recorded only the “substance” of his memorable vision, though twenty-six verses may seem to us like a rather full report. Chapter 7 parallels ch. 2; both set forth the four empires, followed by the complete overthrow of all ungodly resistance, as the final (fifth) kingdom is established on earth to enforce the standards of God’s righteousness. The winged lion corresponds to the golden head of the dream image (ch. 2), the ravenous bear to its arms and chest, the swift leopard to its belly and thighs, and the fearsome ten-horned beast to its legs and feet. Lastly, the stone cut out without hands that in ch. 2 demolishes the dream-image has its counterpart in the glorified Son of Man who is installed as Lord over all the earth. Butch. 7 tells us something ch. 2 does not—the Messiah himself will head up the final kingdom of righteousness.

2–3 “The great sea,” possibly the Mediterranean, symbolizes the turbulent Gentile world (cf. Rev 13:1 and 21:1; cf. also Isa 57:20). Revelation 7:1 portrays the four winds as under the control of four mighty angels; in Rev 9:14, by the River Euphrates, they are bidden to release the winds on the earth so that one-third of humankind will perish in war (v.15). Apparently the four winds represent God’s judgments, hurling themselves on the ungodly nations from all four points of the compass. From the sea (Gentile nations) emerge in succession four fearsome beasts (namely, the empires of Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome), which apparently go on shore to perform their roles.

4 The first beast is a winged lion, whose eaglelike pinions are soon plucked so that instead of flying it stands on the ground. The lion was a symbol of Babylon, especially in Nebuchadnezzar’s time, when the Ishtar Gate entrance was adorned with yellow lions. The final detail—“the heart of a man was given to it”—may refer to the restoration of Nebuchadnezzar’s sanity after his seven-year dementia; plucking the lion’s wings symbolizes the reduction of his pride and power at the time of his insanity (ch. 4).

5 The second beast—a hulking bear—apparently displaces the lion, though there is no mention of any conflict. The description of the bear suggests the alliance of two powers, one dominating the other—namely, Medo-Persia, with Persia dominating. One side of the bear was higher than the other, and it devoured three ribs from some other animal it had killed. This corresponds to the three major conquests the Medes and Persians made under Cyrus and his son Cambyses: the Lydian kingdom in Asia Minor (546), the Chaldean Empire (539), and Egypt (which Cambyses acquired in 525).

6 The third beast—the four-winged leopard with four heads—portrays the division of Alexander’s swiftly won empire into four separate parts shortly after his death (see comment on 8:8). There is no way a quadripartite character can be the Persian Empire, for it remained unified till its end, under the onslaught of Alexander in 334–331.

7 The fourth beast is unlike any known to the human race, “terrifying and frightening and very powerful” (more fearsome than the preceding empires). Its teeth were of iron; hence it would be more crushing in its military power, exploitation, and repression than the other three. Another difference is the ten horns (conceivably two five-pronged antlers). There is an obvious correspondence between these horns and the ten toes of the dream image (ch. 2), and the mention of iron in the teeth suggests the legs and toes of iron in that image. Thus the superior power of the colossus of Rome—as over against the less unified and weaker empires of Greece, Persia, and Babylon—is emphasized in the symbolism of this terrible fourth beast. Its ultimate form in a confederation of ten states is suggested by the horns (cf. note on 2:41).

8 In this latter-day, ten-state federation, a “little horn” emerges as the largest of them all, uprooting and destroying three adjacent horns (apparently subjecting the remaining six to vassalage). The contemporaneity of all ten of these states (or rulers) is virtually demanded, since six remain in subservience to the aggressive little horn. The victorious little horn’s features symbolize an arrogant and vainglorious ruler rather than an entire kingdom (cf. ch. 4, where the Chaldean power is symbolized in the personality of Nebuchadnezzar whereas the bear and the leopard symbolize the Medo-Persian and Greek empires as entire realms). The final clause introduces the ruthless world dictator of the last days (cf. 2Th 2:3–4, 8). This little horn emerges from the fourth empire, unlike the little horn of ch. 8 (vv.9–11), which arises from the third empire (see comments on ch. 8).

B. The Kingdom of God and the Enthroned Messiah (7:9–14)

9–12 The fifth kingdom as the final form of world power overthrows and utterly destroys all the preceding empires erected by violence-worshiping men. Attention is directed to God, “the Ancient of Days” (cf. Eze 1:13). The fire represents the brilliant manifestation of his splendor as well as the fierce heat of his judgment. A lava-like “river of fire” depicts vast destructive power. An enormous crowd stands by as the heavenly court convenes for the examination and conviction of the rebellious little horn (i.e., the final world dictator) and his followers. The record books that are opened presumably contain the sins of the little horn and his adherents (cf. Rev 20:12–13). The blasphemous beast spews out his boastings against humans and God till the very moment he is dragged before the heavenly tribunal. Then his mouth is stopped as his physical life is taken and his body consigned to the flames of judgment. The remnants of the world powers (“the other beasts”) likewise come under judgment. They “were allowed to live for a period of time”; this may mean that the unbelieving world powers that precede the little horn are reserved for judgment by the returning Christ.

13–14 At this point Daniel saw the glorified Son of Man (v.13 is the most frequently quoted verse from Daniel in the NT). The personage who appears before God in the form of a human being is of heavenly origin. He comes to the place of coronation accompanied by the clouds of heaven and is clearly no mere human being in essence. The expression “like a son of man” identifies this final Ruler of the world not only as human, in contrast to the beasts (the four world empires), but also as the heavenly Sovereign incarnate. During his earthly ministry, the Lord Jesus maintained this same emphasis on his incarnate nature (that he was truly human as well as truly God). He repeatedly referred to himself as “the Son of Man” (i.e., that same one foretold in Da 7:13; see comment on Mark 8:31). Moreover, v.13 is the only place in the OT where “son of man” is used of a divine personage rather than a human being. Furthermore, Christ himself emphasized his return to earth accompanied by “clouds” (cf. Mt 24:30; 26:64; Mk 13:26; cf. also Ac 1:9–11; Rev 1:7). Nothing could be clearer than that Jesus regarded Da 7:13 as predictive of himself and that the two elements “like a son of man” and “with the clouds of heaven” combined to constitute a messianic title.

The messianic Son of Man is brought before the throne of the Ancient of Days to be awarded the crown of universal dominion. This picture refers to his appointment as absolute Lord and Judge by virtue of his atoning ministry as God incarnate—the One who lived a sinless life (Isa 53:9), paid the price for the redemption of the human race (Isa 53:5–6), and was vindicated by his bodily resurrection as Judge of the entire human race (Ac 17:31; Ro 2:16). So also his ascension into heaven means that he will be enthroned in glory (Ps 110:1; Ac 2:66) till all his enemies have been subdued (Heb 10:12–13).

The Son of Man is to be the supreme source of political power on earth after his earthly kingdom is established; all humans will worship and serve him. The outcome of human history will be a return of Adam’s race under the rule of the divine Son of Man to loving obedience and subjection to the sovereignty of God (cf. Mt 28:18).

C. The Vision Interpreted by the Angel (7:15–28)

15–18 Despite the victorious conclusion of his dream, Daniel was distressed by his inability to understand several features of it. So he asked an angel standing nearby to explain some of these puzzling details. The angel gave a general reply (vv.17–18) to Daniel’s first question, indicating that the four beasts represented the successive world empires that would dominate the Near East till the last days. But he added that the ultimate sovereignty over the world would be granted to “the saints of the Most High” (cf. v.27). The reason for emphasizing the participation of God’s people in the final kingdom may be because it is a literal, earthly kingdom rather than a spiritual domain.

19–22 Daniel regarded the fourth beast with the greatest curiosity and dread. In particular he wondered about the ten horns and the little horn that emerged and overcame God’s holy people. Despite the assurance that the ultimate victory would be the Lord’s and that his people would finally prevail, Daniel was deeply concerned about their impending persecution.

23 The angel’s answer (vv.23–27) centers on the career of the little horn (cf. 2Th 2:8–9; Rev 13:1–10) and his rise and fall at the second coming of Christ. In v.23 the angel refers to the Roman Empire, which will be markedly “different from” the three preceding empires. Its difference will not be in size (Alexander’s empire far exceeded Trajan’s) but in organization and unity, enabling it to endure for centuries beyond the lifetime of the preceding Near East empires. “The whole earth” refers (as in general OT usage) to the entire territory of the Near and Middle East that in any way relates to the Holy Land. The word translated “earth” (GK 10075), depending on context, might mean a single country or a region. Here it is the portion of the world included in the Roman Empire, or possibly the regions immediately adjacent to it. The Roman state is seen as devouring the surrounding nations bite by bite and thus acquiring an entire complex of subject kingdoms and nations.

24 The interpreting angel turned from the historic Roman Empire to its ultimate ten-horn phase (cf. 2:41–43) and the emergence of the final world dictator. He arises after ten horns have been set up and subdues three of these ten to his own direct rule. He will then subject the other seven states to vassalage.

25 The little horn will claim divine honors (even as he blasphemes the one true God). He will abandon all pretense of permitting freedom of religion and will revile the Lord of heaven and earth. By cruel and systematic pressure he will “oppress” (lit., “wear out”) those with biblical convictions. Such continual and protracted persecution far more effectively breaks the human spirit than the single moment of crisis that calls for a heroic decision. It is easier to die for the Lord than to live for him under constant harassment and strain. This dictator will impose a new legal system, doubtless based on totalitarian principles in which the service of the government or the state will be substituted for the absolute standards of God’s moral law. All opposition to the decisions and policies of the little horn will be adjudged treasonable and punishable by death. His program will include a revision of the calendar (implied by “to change the set times”). This was attempted during the French Revolution.

Significantly, the radical phase of the Beast’s rule endures for “a time, times and half a time,” or three and a half years. This is half of the seven years that mark the period of the little horn’s career. Judging from 9:26–27, it appears that at the beginning of this final heptad of years the “ruler who will come” will “confirm a covenant with many for one ‘seven’ [but] in the middle of that ‘seven’ ” will compel the offering of sacrifices to cease. Thus after the first three and a half years of his career, the Beast will abrogate his “covenant” with the religious establishment (cf. 12:11; Mt 24:15; 2Th 2:4). This would leave three and a half years for his program to be carried out unhindered by any rival theistic ideology.

26–27 The last two verses of the angel’s explanation make it clear that a great day of judgment and destruction on the Beast’s empire and on the whole wicked world will usher in the seating of the Son of Man on the throne of absolute sovereignty and the commencement of the fifth kingdom (cf. ch. 2) administered by his faithful believers. No unsubdued, rebellious elements will be left among the surviving inhabitants of earth; “the sovereignty, power and greatness of the kingdoms under the whole heaven” will be granted to “the saints, the people of the Most High,” indicating that the Son of Man (v.13) is to be equated with the Most High himself. In the final clause a clear difference is made between the plural “saints” and the singular “him,” the one who is called “the Most High,” whose kingdom will be everlasting—words not applicable to a finite human being.

Identification of the Four Kingdoms

© 1985 The Zondervan Corporation

28 Apparently Daniel experienced a tremendous emotional drain as a result of his extended interview with God’s supernatural messenger (cf. Isa 6:5). His facial hue changed because of his inward concern about the severe trials awaiting his people. Yet these solemn disclosures were not proper matters to divulge to anyone else; so apart from writing them down, he kept them to himself.

VIII. The Grecian Conquest of Persia and the Tyranny of Antiochus Epiphanes (8:1–27)

Here the text switches from Aramaic back to Hebrew (see Introduction).

A. The Vision of the Ram, the He-Goat, and the Little Horn (8:1–12)

1 This vision was granted Daniel two years after the previous one (cf. 7:1). It somewhat resembles it in subject matter and in manner of presentation, for it too portrays successive world empires as fierce beasts; and it also culminates in a tyrant described as a “little horn.” Yet there are significant differences in detail between the two chapters, especially regarding the third and fourth kingdoms.

2 Daniel received this new vision either at the Babylonian capital itself or while on a diplomatic mission to Susa, the capital of Elam. The scene Daniel saw in the vision was not Susa proper but rather the Ulai, a wide, artificial canal that flowed near the city. Appropriately enough, this furnished the setting for the rise of the beast representing Persia.

3 The Medo-Persian power is depicted as a large, powerful ram with two formidable horns. Though one horn was larger than the other, the horn that “grew up later” outstripped the former in size. Obviously this refers to the domination of the Persian power over the Median in the federated Medo-Persian Empire that was even then being formed (cf. 7:5, the bear “raised up on one of its sides”). The larger horn came later, even as Cyrus and his Persians came later than Cyaxeres and Astyages of Media.

4 The three general areas of Medo-Persian expansion were westward, northward, and southward. Initially the Medo-Persian troops were nearly invincible; hence the various beasts representing the surrounding nations opposing Persian expansion are described as helpless against the mighty ram. Cyrus had everything his own way and became arrogant over his universal success.

5–7 Verse 5 foretells coming disaster for Cyrus in the figure of a swift, one-horned goat that with one mighty charge shatters the horns of the Medo-Persian ram. First, the goat is described as coming from the west (i.e., Macedonia and Greece, as Alexander did in 334 B.C.). Second, he moves so fast that his hooves barely touch the ground as he charges all the way to the eastern limit of the Persian domain (“crossing the whole earth”). Third, this irresistible invading force is under the leadership of one man rather than a coalition of nations. In vain the ram attempts to withstand the charge of the goat, as the goat hurls himself against the ram—an implied prediction that the Macedonian-Greek forces would launch an unprovoked invasion such as took place in 334. The completeness of Alexander’s victories is fittingly prefigured by this crushing attack on the ram.

Alexander’s conquest of the entire Near and Middle East within three years stands unique in military history and is appropriately portrayed by the lightning speed of this one-horned goat. Despite the immense numerical superiority of the Persian imperial forces and their possession of military equipment like war elephants, the tactical genius of young Alexander proved decisive.

8 “The goat became very great” suggests Alexander’s thrust beyond the borders of the empire he had conquered even into Afghanistan and the Indus Valley (327 B.C.). Or it may refer to the growth in arrogance that led him to assume the pretensions to divinity that distressed his Macedonian troops, who finally mutinied. In support of his claim to have descended from Zeus-Ammon, which had been solemnly announced by the Egyptian priesthood after his liberation of Egypt from Persian tyranny, Alexander had required even his comrades-in-arms to prostrate themselves before him, in conformity with Oriental custom. In accord with his newly conceived imperial policy of granting equality to his Persian subjects along with his victorious Macedonian-Greek supporters, he went so far as to take the Persian princess Roxana as his queen and to designate his future son by her, Alexander IV, as successor to the Greco-Persian Empire.

Yet, as v.8 predicts, “at the height of his [the goat’s] power his large horn was broken off.” Alexander died of a sudden fever brought on by dissipation (though it was rumored that he was actually poisoned by Cassander, the son of Antipater, viceroy of Macedonia) at Babylon in 323, at the age of thirty-three. Although efforts were made to hold the empire together—first by Antipater himself as regent for little Alexander IV (and for Philip III Arrhidaeus, his half-witted uncle), and then, after Antipater’s death in 319, by Antigonus Monopthalmus, another highly respected general—the ambitions of such regional commanders as Ptolemy in Egypt, Seleucus in Babylonia, Lysimachus in Thrace and Asia Minor, and Cassander in Macedonia-Greece made this impossible. By 311 Seleucus asserted his claim to independent rule in Babylon, and the other three followed suit about the same time. Despite the earnest efforts of Antigonus and his brilliant son, Demetrius Poliorcetes, to subdue these separatist leaders, the final conflict at Ipsus in 301 resulted in defeat and death for Antigonus. The four ruthless and powerful generals named above became the “Diadochi” (“Successors”), who partitioned the Macedonian realm into four parts.

The prophecy “in its [the large horn’s] place four prominent horns grew up toward the four winds of heaven” was fulfilled when Cassander retained his hold on Macedonia and Greece; Lysimachus held Thrace and the western half of Asia Minor as far as Cappadocia and Phrygia; Ptolemy consolidated Palestine, Cilicia, and Cyprus with his Egyptian-Libyan domains; and Seleucus controlled the rest of Asia all the way to the Indus Valley. While it is true that various vicissitudes beset these four realms during the third century and after (Pergamum, Bithynia, and Pontus achieved local independence in Asia Minor after the death of Lysimachus; and the eastern provinces of the Seleucid Empire achieved sovereignty as the kingdoms of Bactria and Parthia), nevertheless the initial division of Alexander’s empire was unquestionably fourfold, as this verse and 7:6 (the four-winged leopard) indicate.

9–10 Verses 9–12 foretell the rise of a “small horn” from the midst of the four horns of the Diadochi. It is described as attaining success in aggression against the “south,” or the domains of the Ptolemies. This evidently refers to the career of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (“the Manifest/Conspicuous One”; see comment on 8:23–25), who usurped the Seleucid throne from his nephew (son of his older brother, Seleucus IV) and succeeded in invading Egypt 170–169 B.C. His expeditions against rebellious elements in Parthia and Armenia were initially successful “to the east” as well, and his determination to impose religious and cultural uniformity on all his domains led to a brutal suppression of Jewish worship at Jerusalem and generally throughout Palestine (here referred to as “the Beautiful Land”; cf. 11:16, 41). This suppression came to a head in December 168 B.C., when Antiochus returned in frustration from Alexandria (Egypt), where he had been turned back by the Roman commander Popilius Laenas, and vented his exasperation on the Jews. He sent his general, Apollonius, with twenty thousand troops under orders to seize Jerusalem on a Sabbath. There he erected an idol of Zeus and desecrated the altar by offering swine on it. This idol became known to the Jews as “the abomination of desolation” (cf. 11:31), a type of a future abomination to be set up in the Jerusalem sanctuary in the last days (cf. Mt 24:15).

Some observations are in order concerning the relationship between the “little horn” (lit., “a horn from a small one”) in 8:9 and the “little horn” in 7:8. The horn in ch. 7 emerged from the ten horns of the fourth beast, whereas this horn in 8:9 arises from the four-horned beast that represents the third kingdom, the empire of Alexander the Great (as all critics agree). Since the author of Daniel invests numbers with high significance, there is no possibility that he could have meant to equate a ten-horned beast with a four-horned one. The only plausible explanation is that the little horn arising from the third kingdom is a prototype of the little horn of the fourth kingdom. The crisis destined to confront God’s people in the time of the earlier little horn, Antiochus Epiphanes, will bear a strong similarity to the one that will befall them in the final phase of the fourth kingdom in the last days (see Mt 24:15). In each case a determined effort is made by a ruthless dictator to suppress completely the biblical faith and the worship of the one true God. Rather than concluding that the little horn of ch. 7 is also intended as a prophecy of Antiochus Epiphanes (with a resultant identification of the fourth kingdom as the Greek or Seleucid Empire), we are to understand the relationship between the little horn of the Greek Empire and that of the latter-day fourth kingdom to be that of type and antitype, similar to that between Joshua and Jesus (Heb 4:8) and Melchizedek and Christ (Heb 7). In Da 11 both the typical little horn (Antiochus) and the antitypical little horn appear in succession, the transition from the one to the other taking place at 11:36, after which are predicted the circumstances of the destined death of the antitype that were not at all true of Antiochus Epiphanes himself. Therefore, the two figures cannot be identical, nor can the Greek Empire be equated with the fourth kingdom of Daniel’s prophetic scheme.

Continuing with the predicted career of Antiochus (v.10), we encounter the remarkable statement that he will grow up to “the host of heaven” and will throw “some of the starry host down to the earth,” where he will “trample on them.” “Host” (GK 7372) is a term most often used of the armies of angels in the service of God (e.g., “LORD of hosts” in KJV) or else of the stars in heaven (cf. Jer 33:22). But it is also used of the people of God, who are to become as the stars in number (Ge 12:3; 15:5) and are spoken of as “the LORD’s divisions” (Ex 12:41). Daniel 12:3 states that true believers (lit., “those who are wise”) “will shine like the brightness of the heavens [lit., stars] for ever and ever.” Since the Greek tyrant can hardly affect either the angels of heaven or the literal stars in the sky, it is quite evident that the phrase “the host of the heavens” must refer to those Jewish believers who will join the Maccabees in defending their faith and liberty. It is then implied here that Antiochus will cut down and destroy many of the Jews during the time of tribulation he will bring on them, when he will have “trampled on them.”

From 171 or 170 B.C. and thereafter, Antiochus pursued his evil policy of securing control of the high priesthood and bringing increasing pressure on the Jewish hierarchy to surrender their religious loyalties in the interests of conformity to Greek culture and idolatry. Already in 175, at the beginning of his reign, he had expelled the godly high priest Onias III from office and replaced him with his Hellenizing younger brother, Jason. Before long a certain Jew named Menelaus, who was apparently also of the high priestly family, bribed Antiochus to depose Jason and appoint him high priest in his place. But while Antiochus was successfully campaigning in Egypt against Ptolemy VII (181–145 B.C.), Jason laid siege to Jerusalem in the hope of ousting Menelaus. In the process of dealing subsequently with Jason, Antiochus took occasion to storm Jerusalem and pillage the temple itself. Reinstalling Menelaus as high priest, Antiochus gave him the mandate to continue an aggressive policy of Hellenization. But in December of 168 (cf. above), he had Jerusalem again seized by treachery and subjected it to prolonged looting and massacre, and a year later he converted its sanctuary into a temple to Zeus (Dec. 16, 167). So it continued until that memorable day, three years later, when Judas Maccabaeus rededicated the sacred structure to the worship of God (Dec 14, 164 B.C.), an event celebrated as Hanukkah by the Jewish community.

11 This verse describes how the megalomania of Antiochus advances to such extremes that he will declare himself equal with God (“Prince of the host”). He will halt the regular morning and evening sacrifice. (This was the daily burnt offering ordained in Nu 28:3, consisting of one lamb presented at sunrise and one at sunset, together with flour and oil [Nu 28:5].) This offering presented the atonement of the believing nation, whether or not any other sacrifice was brought before the Lord on that particular day. But the Seleucid tyrant commanded these offerings to be suspended in 168 and substituted a heathen sacrifice presented to an idol of Zeus, after the altar of the Lord had been destroyed and his temple pillaged and desecrated (“and the place of his sanctuary was brought low”).

12 Judah’s three-year tribulation period, during which the temple would be defiled and prostituted to heathen use, is now described. The phrase rendered “because of” is somewhat ambiguous. The verse as a whole probably should be rendered as follows:

And on account of transgression [presumably the transgression of Jason and Menelaus and the pro-Syrian faction among the worldly minded Jews of the Maccabean period] the host [of God’s people, the Jewish believers] will be given up [to the persecuting power of Antiochus IV] along with the [suspended] continual burnt offering; and the horn [Antiochus] will fling the truth [of the scriptural faith and service of God] to the ground [by forbidding it on pain of death], and he will perform [his will, or carry out his program of enforcing idolatry] and will [for the three-year period] prosper.

B. Gabriel’s Interpretation of the Vision (8:13–27)

13–14 There were two or possibly even three “holy ones” (GK 7705; i.e., heavenly beings) conversing about the prophetic meaning of the vision just described. Apparently the second angel (“another holy one”) posed the question to the third (“to him”) as to the duration of the terrible period when the temple and altar of the Lord would be desecrated (v.11). The answer given by the third angel was that this condition would last for “2,300 evenings and mornings.” This period of time has been understood by interpreters in two ways, either as 2,300 twenty-four-hour days (“evening morning” meaning an entire day from sunset to sunset; cf. Ge 1) or as 1,150 days composed of 1,150 evenings and 1,150 mornings. In other words, the interval would either be 6 years and 111 days or 3 years and 55 days. Most evidence seems to favor the latter interpretation. The context speaks of the suspension of the “sacrifice,” a reference to the “continual burnt offering” that was offered regularly each morning and evening. Surely there could have been no other reason for the compound expression than the reference to the two sacrifices that marked each day in temple worship.

Consequently, we are to understand v.14 as predicting the rededication of the temple by Judas Maccabaeus on 25 Chislev (or Dec. 14), 164 B.C.; 1,150 days before that would point to a terminus a quo of three years, one month, and 25 days earlier, or Tishri 167 B.C. While the actual erection of the idolatrous altar in the temple took place in Chislev 167, or one month and 15 days later, there is no reason to suppose that Antiochus Epiphanes’s administrators may not have abolished the offering itself at that earlier date. Verse 14 simply specifies that when the 2,300 evenings and mornings have elapsed, “then the sanctuary will be reconsecrated.” That certainly happened when the first Hanukkah was celebrated on 25 Chislev 164.

15–18 Some other heavenly being not otherwise specified commissioned Gabriel to explain the meaning of the vision to the swooning prophet. Gabriel was instructed to identify the coming world empires and the climactic events of the “time of the end.” The overwhelming splendor of Gabriel’s presence rendered Daniel completely helpless, but the angel’s transforming touch restored him.