INTRODUCTION

1. Background

Joel prophesied in Judah in the exciting and pivotal days of Uzziah (792–740 B.C.), the tenth king of the southern kingdom. Those were days of unparalleled prosperity. To the south Uzziah continued the control over Edom that Amaziah had effected (2Ki 14:22; 2Ch 26:2); he also seized the caravan routes that led from Arabia (2Ch 26:7). To the east he seems to have imposed tribute on the Transjordanian regions (v.8). To the west he moved with great success against the Philistines, taking Gath and the coastal plain, thus controlling the important trade routes (vv.6–7) and eliminating the slave-gathering raids into western Judah (3:4–8). A great military strategist, Uzziah’s military preparedness included a total reorganization of the structure and equipment of the army (vv.11–15).

About 750 B.C., Uzziah contracted leprosy because of his intrusion into the priest’s office, and he appointed Jotham, his son, as coregent and public officiator. Nevertheless, Uzziah continued to be the real power of the throne, for when Tiglath-pileser III invaded Syria in his first western campaign (743 B.C.), Uzziah was singled out as the leader of the anti-Assyrian coalition. Uzziah also turned his attention to the internal affairs of his country. Indeed, most of his military activity had economic goals. He also led the way in agricultural reorganization (2Ch 26:10).

In short, the era of the early eighth century B.C. was one of great expansion—militarily, administratively, commercially, and economically; it was a period of prosperity second only to that of Solomon’s. It is small wonder, then, that Uzziah’s fame should endure long after his death (2Ch 26:8b, 1:5b).

In such an era God raised up the great writing prophets, men of intense patriotism and deep spiritual concern. Their message took in the entire international scene from their own time to the culmination of God’s teleological program.

2. Authorship

Little is known of the personal circumstances of the author, Joel (“The Lord is God”), except what can be gleaned from the book. The son of Pethuel, Joel lived and prophesied in Judah (cf. 2:32; 3:1, 17–18, 20). He was thoroughly familiar with the temple and its ministry (1:9, 113–14, 16; 2:14, 17) and was intimately acquainted with the geography and history of the land.

Joel was a man of vitality and spiritual maturity. As a keen discerner of the times, he delivered God’s message to the people of Judah in a vivid and impassioned style.

3. Date

Since no date is given, conjectures have ranged from the ninth century B.C. to the Maccabean Period (i.e., either preexilic or postexilic). The preexilic date is the better of these two.

Three general positions have been advanced by those who assign a preexilic date to Joel-the ninth century, the eighth century, and the seventh century. The view that Joel prophesied in the early eighth century is to be preferred because it best fits all the data: (1) the nonmention of Assyria, Babylonia, and Persia, best explained by Assyria being in severe decline from 782 B.C. to 745 B.C.; (2) the position of Joel among the dated minor prophets (with Hosea, Amos, Jonah); (3) the contextual juxtaposition of six foreign nations in ch. 3; (4) the internal emphases; (5) the faithful reflection of the prevailing events, attitudes, and literary themes of the early eighth century B.C.; and (6) Joel’s prophecy of the Day of the Lord, which may be connected with Amos’s dating of his prophecy as two years before the earthquake of Uzziah’s time (1:2; cf. Zec 14:5).

4. Occasion and Purpose

A locust plague without parallel had descended on Judah, ruining all the crops. All levels of society were disrupted. Worst of all, the agricultural loss threatened the continuance of the sacrificial offerings. In these circumstances Joel saw the judgment of God on Judah. The people in Uzziah’s day had taken God and his blessings for granted. Faith had degenerated into an empty formalism and their lives into moral decadence. To Joel, the locust plague was a warning of a greater judgment that was coming unless the people repented and returned to fellowship with God. If they did, God would pardon them, restore the health of the land, and give them again the elements needed to offer the sacrifices.

5. Theological Values

As a man of faith in God, Joel imparted a reliance on the sufficiency of God and his prior claim on the believer’s life. His basic tenet is that God is sovereignly guiding the affairs of world history toward his preconceived goal (1:15; 2:1–4, 25–32; 3:1–21). He alone is God (2:13)—a God of grace and mercy (2:13, 17), of love and patience (2:13), and of justice and righteousness (1:15; 2:23; 3:1–8). He calls for true worship from his followers, who have trusted him for salvation by grace through faith (2:32). Mere external worship is insufficient before the Lord (2:13, 18–19, 23, 26–27, 32).

Joel also taught that when sin becomes the dominant condition of God’s people, they must be judged (1:15; 2:1, 11–13). God may use natural disasters (ch. 1) or political means (2:1–11) to chastise his people. If the people repent (2:12–13), they will be restored to fellowship with God (2:14, 19, 23), and nature too will be restored to blessings (2:23–27).

Joel’s theology also contains teaching about the last things. Of central concern is God’s role to his people Israel (1:6, 13–14; 2:12–14; et al.). While he may allow other nations to chastise Israel for her sins, God has reserved a remnant for himself (2:28–32). On them he will pour out his Spirit (2:28–29), to them he will manifest himself with marvelous signs (2:30–31), and them he will regather and bring to the Promised Land (2:32–3:1). He will gather for judgment those nations that have dealt so severely with his people (3:2, 12–13) and bring them to a great final battle near Jerusalem (3:9–16). On that awesome day (v.15), he himself will lead his people in triumph (vv.16–17) and usher in an era of unparalleled peace and prosperity (vv.17–21).

EXPOSITION

I. Joel’s Present Instructions: Based on the Locust Plague (1:1–2:27)

A. The Occasion: the Locust Plague (1:1–4)

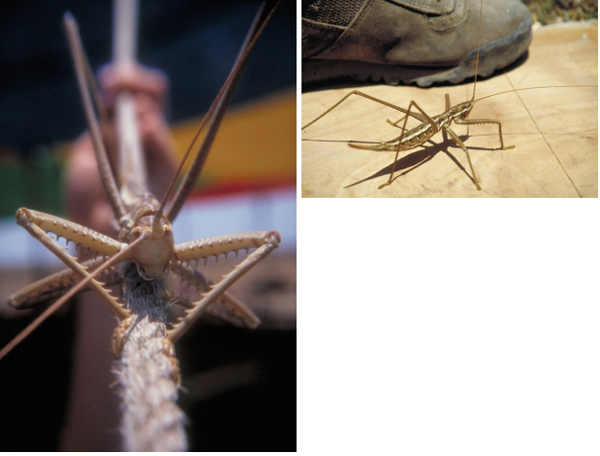

1–4 Joel begins his prophecy by identifying himself and his lineage and clearly declaring the divine source of his prophecy. Because the intensity of the locust plague was unprecedented, this message was to be handed down to the generations that followed. The four different Hebrew words for locusts that appear in v.4 probably are used to indicate the intensity of the plague and a successive series of locusts that had devastated the land.

B. The Instructions: Based on the Locust Plague (1:5–2:27)

1. Warnings in the light of the present crisis (1:5–20)

a. Joel’s plea for penitence (1:5–13

5–7 Joel begins his call for penitence with a solemn warning to three categories of pleasure seekers—the general citizenry, the farmers, and the priests. He tells them to awaken from their sleep of drunkenness (cf. Pr 23:35b). In so doing he calls attention to not only the debased nature of society but also the people’s insensitivity to their own moral condition. Times of ease and prosperity, such as were experienced during the kingship of Uzziah, are unfortunately often times of spiritual, moral, and social corruption.

Joel condemns the misuse of wine, which had led to drunkenness, debauchery, and the loss of spiritual vitality. As a result, the locusts, like a powerful army, had stripped bare the vegetation of the land. These voracious insects had teeth like a lion’s. The vine and the fig tree, symbols of God’s blessing, lay stripped to the bark.

8–10 Far worse than the locust plague was the condition of the people’s spiritual lives. The very worship of God was being compromised. Joel instructs the citizenry to mourn like an engaged virgin whose intended husband was taken from her before the wedding. How great would be her tragedy and sorrow! So also the people of Judah and Jerusalem should weep over the loss of vital religious experience through the devastation of the land. The loss of agricultural produce meant the early cessation of the meal (grain) and drink offerings. The cutting off of them should have been a warning to the people of their grave condition.

The observances of these offerings had degenerated in Joel’s day into mere routine ritual (cf. Hos 6:6; Am 4:4–5). Still worse, the Israelites had made these times an occasion for drunkenness (Hos 2:5; Am 2:8). Therefore, as he had warned, God had taken away the privilege of offering that which symbolized purity of devotion. The cutting off of the sacrifices was a severe step of chastisement, though it should also have warned the people of their grave condition.

Joel notes that the priests, the ministers of the Lord, were mourning. The once productive fields were utterly laid waste (cf. Mic 2:4), and the very ground grieved like the priests (cf. Am 1:2). Grain (wheat after threshing), wine (the freshly squeezed fruit), and oil (the fresh juice of the olive) were all considered objects of God’s blessing. These were being withdrawn as punishment for their sins (Hos 2:8–13).

11–12 Joel also calls on the farmers and vine keepers to “despair” (cf. Job 6:20; Isa 1:29; 20:5) and to “wail” (cf. v.5), lamenting the loss of the products of the field and of the vineyard and orchard, which symbolized the blessings of the relationship between God and Israel (see Ps 80:8–15; Isa 5:21–6; Jer 2:21; cf. Mt 21:18–21, 28–46). Joel also mentions other trees that were not only important to the economy but were symbols of spiritual nourishment, refreshment, joy, and fruitfulness in the life of the believer (cf. Dt 8:6–10; Ps 92:12; SS 2:3).

13 Joel closes this section with a special plea to the second specially affected segment of society—the priests. They were to gird themselves with sackcloth and to mourn and wail. The prophet demonstrates the urgency of the situation by pleading with them to spend the whole night in their garments of contrition and penitence (cf. Est 4:1–4), because of the loss of the daily sacrifices.

b. Joel’s plea for prayer (1:14–20)

14–18 Because the locust plague warned of a still further and more drastic judgment, Joel calls for a solemn assembly for prayer. The priests were to convene the people at the temple for a solemn fast and a season of prayer (cf. Ne 9:1–3; Jer 36:9). The prophet was concerned that the people give a fervent cry of repentance and call on God for forgiveness, lest a greater judgment descend soon.

The reason for the repentant cry was that the Day of the Lord was at hand. The locust plague was a dire warning that the Lord’s judgment of Judah was imminent. That Day of the Lord was not to be one of vindication for Israel but was to signal its demise (Am 5:16–20). Not only was the Day imminent, it was certain—“like destruction from the Almighty.”

The need for penitence and prayer ought to have been obvious from the terrible conditions. Their food had been cut off so that there could be no feasts or offerings of gladness. Worst of all, this had affected the worship in the house of “our God.” The physical world too was a shambles. The unfructified grains lay shriveled under their hoes, the barns were desolate, and the granaries were trampled down. All the cattle were without pasturage.

19–20 As an example to the people, Joel breaks forth in a cry to the Lord who alone could forgive and deliver. He again speaks of the loss of pasturage as well as of the trees. What the locusts had not destroyed, a severe summer’s heat and drought ruined.

Likewise, the beasts of the field were longing for God. They had to seek higher ground because of the loss of pasture and because the streams had dried up. Joel intimates that they were more sensitive to the basic issues at hand by their panting for God than were God’s own people (cf. Isa 1:3). God’s message was plain. The barrenness of the land reflected the dryness and decay of the hearts of the people. If their hearts remained unmoved and unrepentant, a worse judgment loomed ahead.

2. Warnings in the light of the coming conflict (2:1–27)

a. Joel’s plea for preparation (2:1–11)

1 With the picture of the locust plague before him and the warning of judgment firmly in mind (1:15), Joel portrays a coming army—namely, the Assyrian army of the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. The appearance and activities of the locusts were analogous to a real army. The fitness of the image is seen in Joel’s account: in the darkening of the day (vv.2, 10), in the suddenness of the locusts’ arrival (v.2), in their horselike appearance (v.4), in the orderliness of the battle (vv.7–8), and in the ubiquitous nature of their devastation (vv.3, 9). Both locusts and armies are known to be the instruments of God’s chastening (e.g., Dt 28:38–39; 1Ki 8:35–39; Isa 45:1; Am 4:9). Yet the imagery goes beyond a literal locust plague in 2:1–11 (e.g., vv.3, 6, 10), especially as amplified in the spiritual challenge based on this event in 2:12–27 (cf. vv.17, 20, 26–27).

Joel saw the invaders spread out before the walls of the city. Therefore he cried, “Blow the trumpet . . . sound the alarm!” The trumpet (GK 8795) was made from a ram’s horn and was used from earliest times as a signal to battle (e.g., Jdg 3:27; 6:34) or (as here) a signal of imminent danger (e.g., Hos 5:8; 8:1; Am 3:6). “My holy hill” stresses the spiritual basis of the situation. At the sound of the alarm, all would tremble because of the fearfulness of the events that were to take place. It was the Day of the Lord, seen as having arrived in all its frightful consequences!

2–3a That “day” of judgment will be one of darkness and gloominess, of clouds and thick darkness (cf. Am 5:18–20). With the suddenness of dawn spreading over the mountains, a mighty army has appeared, which cast its shadow over the entire face of the land. This army was unrivaled in records prior to Joel’s day, and even then Assyria’s fall would be due as much to inner stresses as to the combined efforts of the Scythians, Medes, and Babylonians.

3b What had been a scene of beauty would become a picture of utter desolation. Nothing in the land would escape.

4–6 The double figure of locusts and armies must be kept in mind. On the one hand, the locusts had appeared like horses (cf. Job 39:19–20; Rev 9:7). Not only had their swiftness and orderly charge been like a well-disciplined cavalry unit, but their very form was horselike. The clamor of the locusts’ flight had been like the din of the dreaded war chariot or the crackling of blazing stubble ignited by a wild fire. The regularity of their advance had been like that of men set in battle array. The awesomeness of their approach had caused great anguish of heart.

On the other hand, Joel relates the dreadfulness of that past scene to the coming devastation by the Assyrian army. He notes first the approach of the war horses, then the frightful war chariots as they crested over the mountain passes above the cities of Judah. He compared the swiftness and noise of their advance to wild fire. He notes the uniformity of the charge of the finely trained and unstoppable host. If the locusts had caused terror, how much more the human invaders!

7–9 The attack of that mighty army was like a locust swarm. They performed as heroic warriors: they climbed the walls of the city, rushed through its streets, and reached the innermost recesses of every place. The mighty men of war first rushed against, then over the walls. All the while each moved straightforward (cf. Jos 6:5), holding his rank and course. Joel depicts the invincibility of the invading soldiers as they unswervingly continued through the city’s defenses. Their attack was powerful and swift; they rushed unrestricted throughout the city.

10–11 Joel brings this section to a close by explaining this army’s sure success. Its leader was none other than the omnipotent and sovereign God himself. Utilizing epithets that were well-known to every Israelite since the Exodus, Joel depicts God as moving with great might before the Assyrian host, “his army.” There were signs on earth (a great shaking) and in heaven (the luminaries darkened). Before the advancing army the thunderstorm raged. The sight of the Assyrian host ought to have been enough to strike terror into the hearts of the people. The accompanying signs of God’s visible presence leading that powerful battle array would melt the stoniest of hearts. It was nothing else than the day of the Lord’s judgment against his own. Who could endure his visitation?

b. Joel’s plea and prescription (2:12–27)

12–14 By means of the introductory phrase “‘Even now,’ declares the LORD,” Joel presents God’s concern for his people. Joel pleads with the people for broken and contrite hearts (cf. Ps 51:17): “Return [GK 8740] to me.” After reiterating his plea, Joel gives the grounds for its acceptance: God is a God of grace and mercy, who not only has compassion for all in their need (cf. Jnh 4:2), but is a God of love who has revealed himself in redemptive grace (cf. Ex 34:6). God is slow to anger, abundant in his righteous concern for the spiritual welfare of humankind, and willing to forgive people in their evil condition: “He relents from sending calamity.”

Since judgment is conditioned on one’s failure to meet God’s standards, for a person to repent and meet God in his gracious provision is to avert the just judgment. From a human point of view, God would seem to have “changed his mind” or “repented concerning the evil” (cf. Ex 32:14; 2Sa 24:16). God might even restore the forfeited blessings and the fertility of the land so that the discontinued sacrifices might again be offered, this time out of a pure heart.

15–17 Joel issues another call for a solemn assembly (cf. 1:14), this time to convene the people in the light of the revealed invasion that stood so near. All must meet with God and listen to his commandments and act on them.

The priests were to be the first to experience repentance in their lives. Then they were to lead the people in doing the same. The main business was to implore the God of all grace to spare his people, not only for their good, but also that his inheritance be not a reproach before the world or his name be brought into disrepute because of what they had done.

18–19 God promises the repentant heart that his godly jealous love (as a husband for his wife) would move him to have pity on his people. He would immediately restore all that had been lost in the locust plague; they would be fully satisfied (cf. Dt 6:10–11; 8:7–10; 11:13–15) and would no longer be a reproach among the nations.

20 God also pledges to remove “the northern army,” most likely a reference to a foreign invader (i.e., the Assyrians) descending from the north. This prediction is built on the incident of the locust plague. If the people would turn to God in genuine repentance, he would drive that army into a dry and desolate land, no doubt the desert west of the Dead Sea and south and southeast of Judah.

A further reason for this turned-about condition, despite her being the Lord’s army, would be that Assyria’s haughty pride would cause her to leave proper bounds (cf. Pss 35:26; 38:16; cf. also La 1:9), bragging and assuming that the great destruction she was effecting would be her own doing (cf. Eze 35:13; Da 8:4, 8, 11; 11:36–37).

21–27 Should the people truly repent, not only would God’s promises of restoration, rest, and protection be theirs, but certain additional benefits would accrue. The message was one of comfort: “Be not afraid.”

The first object of God’s consoling words was the ground that had suffered so much. It would rejoice and be glad (cf. 1:16); for God himself, who does great things (v.20), would undertake for it. Next God’s comfort was directed to the beasts of the field (cf. 1:18–20), who would have an abundance of food. Furthermore, the fig tree and the vine (cf. 1:7, 12), symbols of Israel’s relation with her Lord, would bear again in full strength.

This leads to the third and central object of divine solace: Israel herself. The “people of Zion” (all true Israelites) were to rejoice and be glad in the Lord their God, for he would restore them in righteousness. He would send again the refreshing former and latter rains. The arrival of “autumn rain” (at the beginning of the rainy season, Oct-Nov) and the “spring rain” (Mar-Apr) on proper schedule would demonstrate the blessing of God on those with repentant hearts (cf. Dt 11:13–17; Jer 5:24–25; Hos 6:1–3).

Joel next mentions God’s supplying the people’s third need: renewed provisions—threshing floors filled with grain, vats overflowing with wine and oil. God would thoroughly restore the years that the devastating plague had caused them to lose (cf. 1:4, 10, 17; 2:19). Whereas the locust plague had brought on famine, the people would now experience the full satisfaction of an abundance of food (cf. 2:19). Therefore, they could praise God in the full knowledge of all that his revealed name signifies (cf. Ex 6:3; Dt 12:7; Pss 8:1–2; 66:8–15; 67:57; Am 5:8–9; 9:5–6).

The restored fellowship would be attested by God’s renewed designation of them as “my people.” They need never again “be shamed,” whether by locusts (1:11), among the heathen (2:17), or before the whole world (cf. Isa 29:22; 49:22–23; 54:4). Best of all they would know the abiding presence of God himself, dwelling in their midst (cf. 2:17; 3:17, 21; Hos 11:9).

II. God’s Future Intentions: the Eschatological Program (2:28–3:21)

A. The Promise of His Personal Provision (2:28–32)

Since the previous section dealt with the near future, presumably the events prophesied here lay still further beyond. Indeed, these chapters disclose the Lord’s eschatological interventions. Utilizing an apocalyptic style that was even then just emerging, Joel stresses two primary thoughts: the Lord’s promise of personal provision in the lives of his own (2:28–32) and the prediction of his final triumph on behalf of his own at the culmination of human history (ch. 3).

1. The outpouring of the Spirit (2:28–31)

28–31 The Lord first promises that he will “pour out” (GK 9161) his Spirit. Hosea prophesied that the Lord must pour out his fury on an idolatrous Israel (5:10); Joel sees beyond this chastisement to the distant future (cf. Eze 36:16–38), when in a measure far more abundant than the promised rain (cf. 2:22–26) God would pour out his Holy Spirit in power. In those days (cf. Jer 33:15) that power would rest on all (i.e., human) flesh (cf. Isa 40:5–6; 66:23; Zec 2:12–13).

God’s covenant people are primarily in view. Joel points out that what the Lord intended is that his Holy Spirit would be poured out on all believers, regardless of their age, sex, or status. It would be a time of renewed spiritual activity: prophesying, dreams, and visions (cf. Nu 12:6).

As visible signs of his supernatural intervention, God would cause extraordinary phenomena to be seen in nature. Although the heavens are mentioned first, the order that follows is one of ascending emphasis, beginning with events on earth (blood, fire, and smoke) and moving to signs in the sky (sun and the moon).

The earthly phenomena are no doubt principally concerned with the sociopolitical upheaval in that day: the blood and fire referring to warfare (cf. Nu 21:28; Ps 78:63; Isa 10:16; Zec 11:1; Rev 8:8–9; 14:14–20; et al.) and the rising smoke to gutted cities (cf. Jdg 20:38–40)—though God’s activity in the natural world may also play a part (cf. Ex 19:9, 16–18; Rev 6:12, 17). These are to be recognized as well-known signs of the presence of a holy God (for blood, cf. Ex 7:17; 12:22–23; for fire, cf. Ex 3:2–3; 13:21–22; Eze 1:27; Ac 2:3; Heb 12:18; Rev 1:14; for smoke, cf. Ex 19:16–18; Isa 4:4–5; 6:4; Rev 15:8). The very signs speak of a redeemed and refined people eager to do God’s will and to carry his message to a needy generation standing under his just judgment.

The heavenly phenomena are also portents of a miraculous nature. There will be a full eclipse of the sun by day (cf. 3:15; Am 5:18–20; 8:9; Zep 1:15); by night the moon will appear to be blood red, perhaps due to conditions caused by an accompanying earthquake (cf. Jer 4:23–24; Rev 6:12–13). All these will signal the advent of that great and terrible Day of the Lord. If the Day of the Lord in the Assyrian invasion would be “great” and “dreadful” (2:11), how much more the eschatological time designated “the great and dreadful day of the LORD”!

The Day of the Lord thus deals with judgment. As to the time of judgment, it could be present (1:15), the near future (Isa 2:12, 22; Jer 46:10; Eze 13:5; Am 5:18–20), the future-eschatological (Isa 13:6, 9; Eze 30:2–3; Ob 15; et al.), or the purely eschatological (Joel 3:14–15; Zec 14:1–21; 1Th 5:1–11; 2Th 2:2; 2Pe 3:10–13). The Day of the Lord, eschatologically speaking, also deals with deliverance for a regathered, repentant Israel (Joel 3:16–21; Zec 14:3; Mal 4:5–6). The NT further reveals that the eschatological Day of the Lord closes with the return of the Lord in glory (Rev 19:11–16) and the Battle of Armageddon (Rev 16:16; 19:17–21; cf. Eze 38–39), continues through the Millennium (Isa 2:1–4; 11:1–12:6; Mic 4:1–5; Rev 20), and culminates in the eternal state (2Pe 3:10–13; Rev 21–22).

2. The outworking of salvation (2:32)

32 Along with the outpouring of the Holy Spirit will be the outworking of salvation for those who truly trust God as Redeemer. To “call on the name of the LORD” is to call on him in believing faith (Pss 99:6; 145:18; Ro 10:3), which gives not only physical deliverance but a spiritual transformation and an abundant entrance into that great millennial period of peace and prosperity, when Judah and Jerusalem are once again spiritual centers for a redeemed Israel (cf. Hos 3:5; Mic 4:6–8).

Joel closes the chapter by balancing this thought with another truth. While salvation-deliverance will be the experience of the one who truly “calls on the name of the LORD” (cf. 2:26) in that day, it is God himself who will summon that remnant.

In Acts 2 Peter viewed Joel’s prophecy as applicable to Pentecost (see Ac 2:16). Both his sermon and subsequent remarks are intimately intertwined with Joel’s message (cf. Joel 2:30–31 with Ac 2:22–24; Joel 2:32 with Ac 2:38–40). The intent of Joel’s prophecy was not only the restoration of prophecy but that such a gift was open to all classes of people. The Spirit-empowered words of the apostles on Pentecost were evidence of the accuracy of Joel’s prediction; they were also a direct fulfillment of Christ’s promise to send the Holy Spirit; see Lk 24:49; Jn 14:16–18; 15:26–27; 16:7–15; Ac 1:4–5, 8).

Peter affirmed that Joel’s “afterward” must be understood as “in the last days” (cf. Joel 2:28 with Ac 2:17). The point of Peter’s remark in Ac 2:16 must be that Pentecost, as the initial day of that period known as “The Last [Latter] Days,” will culminate in the return of Jesus and thus certifies the start and character of those final events.

It must also be noted that the outpouring of the Spirit is an accompanying feature of that underlying basic divine promise given to Abraham and the patriarchs, ratified through David, reaffirmed in the terms of the new covenant, and guaranteed in the person and work of Jesus the Messiah (cf. Ge 12:1–3; 15; 17; 2Sa 7:11–29; et al.). At Pentecost two streams of prophecy meet and blend together: Christ’s prophetic promise is directly fulfilled; Joel’s prophecy is fulfilled but not consummated. It awaits its ultimate fulfillment in the Day of the Lord and the events distinctive to the nation of Israel.

B. The Prediction of His Final Triumph (3:1–21)

1. The tribulation program (3:1–17)

a. The coming of judgment (3:1–8)

1–3 Joel has a new and important announcement. In those future times (cf. 2:29) in which God deals kindly with his covenant people (cf. Jer 33:15–18), he will gather all nations together (cf. Zep 3:8) and enter into judgment with them in the Valley of Jehoshaphat concerning the treatment of his own (cf. Ro 11:25–26).

Judah and Jerusalem will once again be the center of God’s attention. The time involved in vv.1–17 is that of the Great Tribulation—a period of Jacob’s trouble (cf. Jer 30:7 with Mt 24:21; Mk 13:19, 24) and of great affliction for Israel (Dt 4:30; Da 12:1), a period culminated by God’s outpoured wrath against the sinful nations of earth (Isa 13:9, 13; 26:20–21; Zep 1:15–18; Ro 2:5–10; 1Th 1:10; 5:10–11; 2Th 1:6–7; Rev 6:16–17; et al.) and the return of Christ in glory and to judgment (Mt 24:27–31; Mk 13:24–27; Rev 19:11–21).

“The Valley of Jehoshaphat” (lit., “the valley of judgment”), where God enters into judgment with the nations, is not a known valley, as the wordplay makes clear. Joel subsequently called it “the valley of decision” (v.14). The broad valley in the Jerusalem area formed in connection with a cataclysmic earthquake will either be the scene of earth’s final battles or will be the climactic stroke in them.

In v.2c, God rehearses the charges against the heathen nations. First, they had scattered his people among the nations, not only after the Fall of Jerusalem, but in their continued dispersion and persecution up to the end times. God himself would have to call his people back to his land (cf. Jer 50:17–26). Second, though the people had divided God’s land (cf. Am 7:17), he had not renounced his claim to his people or to his land. Third, so cheaply were his people valued that the heathen had cast lots for them and, even worse, had sold a boy for a prostitute’s hire and a girl so that they might drink a flask of wine.

4–8 Joel next records God’s solemn promise of the sure execution of his judgment on the nations. He begins with God’s question as to their purposes regarding himself. The districts of western Canaan, Tyre, and Sidon (well-known slave dealers in the ancient world) and the Philistine coast (often condemned with the Phoenicians by the prophets) are singled out as the primary enemies of Judah, who committed the most inhuman of all crimes—dealing in human merchandise. God warns them that if they would now add insult to injury by taking vengeance without cause against the Lord himself, they could be assured that God would most swiftly repay them in just kind.

The detailed charges against the nations are that they had taken the silver and gold of God’s people (probably by plundering their handsomely furnished houses) to their palaces. Furthermore, they had sold the Jewish children into the hands of the Greek slave-traders, sending them far away.

God warns these enemies that he would righteously repay them in kind (cf. Isa 24:14–23; 2Th 1:6–8), while arousing his dispersed and captive people from the distant lands of their bondage. As he had warned them (v.4), he would give those slave dealers a taste of their own medicine. Their people would in turn be sold into captivity by the children of Judah to the Sabeans who would send them far away.

Joel’s prophecy, though intended for the end times, is also made historically applicable by being based on the current situation of his day. Not only would the great coalition of the future surely fall, but Uzziah’s recapture of Ezion-Geber and his successes against the Philistines served as a warning of the dangerous position in which these allied commercial enemies of Joel’s day stood.

b. The challenge in judgment (3:9–17)

9–12 The Lord’s message is to be circulated among the nations (cf. Am 3:6–11). All the men of war were to assemble and prepare themselves in accordance with the proper spiritual rites before battle (cf. 1Sa 7:5–9), for in the final analysis theirs was to be the culmination of all holy warfare. The mighty men of battle were to be called up for duty (cf. 2:7). All segments of society and the economy were to be on a wartime footing. The basic agricultural tools were to be fashioned into weapons; weak and cowardly men were to count themselves as mighty men of war. The nations were soon to learn that the Lord too was mighty in battle (cf. Ex 15:3: Ps 24:8).

The surrounding nations are next commanded to come quickly and gather themselves together (cf. Pss 2:1–2; 110:1–3, 5–6) to that great final struggle that will culminate earth’s present history (cf. Isa 17:12; 24:21–23; Mic 4:11–13; Zec 12:2–33; 14:1–3; Rev 16:14–16; 19:17–19). The thought of this climactic event causes the prophet to exclaim, “Bring down your warriors, O LORD!”—a reference to the angelic host (cf. Dt 33:2b–3; Pss 68:17; 103:19–20; Zec 14:5) of our mighty God. Whereas God’s mighty ones had been the Gentile armies (ch. 2), God was now against those forces. Joel cries out for their just destruction.

The nations are bidden to come to the Valley of Jehoshaphat (see comment on v.2). The Lord had warned that he would enter into litigation with the enemies of his people; now he sits as judge to impose sentence on them (cf. Isa 28:5–6; Mt 25:31–46).

13–17 God is pictured as sending his reapers into the harvest field (cf. Rev 14:14–20) and to the winepress of judgment (Isa 63:3), for the nations are ripe for judgment; their wickedness is great and filled to overflowing. The confused and clamoring throng of nations and the tumultuous uproar and din of battle in this great day of reckoning are vividly portrayed (cf. Eze 38:21–23; Zec 14:13). The valley named Jehoshaphat (3:2, 12), in accordance with its purpose of being the place of final accomplishment, is now called “the valley of decision.”

The accompanying signs in the natural world are depicted. What was applicable to the local scene of impending battle in the day of the Assyrian invasion (2:10b) is now seen in all its final intensity. The Lord comes forth out of Zion as a roaring lion (cf. Am 1:2). Because the nations had roared insolently against God’s people (Isa 5:25–30), the Lord would be as a lion roaring after its prey in behalf of the returned remnant (cf. Hos 11:10–11 with Jer 25:30–33). Heaven and earth will tremble at his presence among the nations (cf. Ps 29; Isa 29:6–8; 30:30–31; Zec 14:37; Rev 16:16–18).

But the very manifestation of his coming, so fearful for the nations (cf. Rev 6:12–17), gives assurance of protection and strength for God’s own (cf. Isa 26:20–21). As Israel had learned of God’s sovereign concern for his people through judgment (cf. Eze 6:7), now she would know of his eternal compassion through her deliverance and his abiding presence with her (cf. 2:27). In contrast to the nations who would learn who God really is (cf. Eze 6:36–38; 39:6–7), Israel would know the redeeming power and the continuous enjoyment of his glorious presence with her forever (cf. Isa 49:22–26; Jer 24:7; Eze 34:27–30; Zec 2:8–9; et al.). Because the Lord himself is there (cf. 2:32; 3:21), Jerusalem will be everlastingly holy (cf. Isa 52:1; 60:14, 21; Zec 14:21; Rev 21:2). None but his own shall again set foot in it.

2. The millennial prosperity (3:18–21)

18 Joel looks beyond the great battle to the resultant millennial scene. He concludes his prophecy by contrasting the judgment of the nations—typified by Israel’s most protracted antagonist, Edom, and by her most persistent source of spiritual defeat, Egypt—with the blessings that will rest on the repentant, restored, and revitalized people of God.

In glowing and hyperbolic terms, Joel describes the great fertility of soil of the coming Millennial Age. What had been cut off in the locust plague of Joel’s day due to sin (1:5) will be commonplace in that era permeated by the presence of the Holy One (cf. 2:19–27; Isa 55:1). The formerly barren hills will flourish again with vegetation. The wadis, dried by the drought of God’s judgment, will flow again, giving renewed vitality to the land, as God pours out his blessing on people of renewed spiritual vitality (cf. Isa 30:25–26; Eze 34:13–14).

In Jerusalem a fountain will issue forth from the house of the Lord. Ezekiel (47:1–12) reported that it will terminate in the Dead Sea, transforming it from salt water to fresh water. Zechariah (14:8) spoke of a great flow of water from Jerusalem emptying into both the Dead Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, a prophecy that, once incredible, now stands authenticated by recent geological discoveries.

Joel goes on to say that these waters will gush through the Wadi Shittim (see NIV note). The exact location of this place is uncertain and has occasioned many suggestions. Perhaps the best solution is to identify it with a barren valley east of Judah, where the Israelites suffered spiritual failure before making the last encampment prior to their entrance into the Promised Land (cf. Nu 25:1; 33:49; Jos 3:1).

19 Joel next contrasts the future condition of Judah and Jerusalem with that of Egypt and Edom, longtime adversaries of Israel. In contrast with their desolation, Judah and Jerusalem will be inhabited forever. All Judah’s sins will be forgiven, and the Lord himself will abide in her midst forever (cf. Eze 48:35).

20–21 Joel’s last prophetic view is a picture of Israel’s everlasting felicity. The reason for this state of unending happiness is apparent. The Lord himself will “dwell” (GK 8905; related to the word “tabernacle,” GK 5438) in her midst in all his glory (cf. 3:17; Zec 8:3–8). From the Hebrew word shakan used here, theologians have spoken of the Lord’s “shekinah glory.” Throughout the OT this shekinah glory designates the active presence now of the invisible God who transcends the universe he created. However, because of the spiritual and moral decay that had led to religious formalism and open idolatry, that glory left the temple and Jerusalem (Eze 10; 11:22–25) to return not at all till that day of God’s future temple (Eze 43:1–12), when God would again redeem his people and dwell among a repentant, regenerated, and grateful people (Zec 2:10–13).

Before that millennial scene, the NT writers reveal that God has another “tabernacling” with people. His unique Son became flesh, dwelling among us (Jn 1:14) as the promised Immanuel (Isa 7:14). Having redeemed a lost humanity through his death and resurrection, and being ascended into heaven, he now dwells in his own whom he has taken into union with himself (Eph 1:15–2:21; Col 1:15–22, 27; 2:9–10). As the triumphant Redeemer, he has given to the church, his body, gifts of which it is steward (Eph 4:8–10). The believer’s destiny is to enjoy God’s presence forever (Rev 21:2–3).

The Old Testament in the New

| OT Text | NT Text | Subject |

| Joel 2:28–32 | Ac 2:17–21 | God’s Spirit poured out |

| Joel 2:32 | Ro 10:13 | Salvation in the Lord |