INTRODUCTION

1. Background

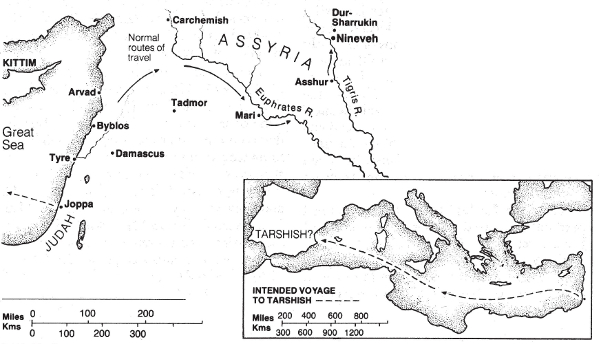

The book of Jonah is the fifth of the Minor Prophets (the Book of the Twelve). Jonah, the son of Amittai, from Gath Hepher in Galilee (cf. 2Ki 14:25; Jos 19:13) prophesied during or shortly before the reign of Jeroboam II (793–753 B.C.). This makes it virtually certain that we should place the story of the book in the period of Assyrian weakness between the death of Adad-nirari III in 782 B.C. and the seizing of the Assyrian throne by Tiglath-pileser III in 745 B.C. During this time, Assyria was engaged in a life and death struggle with the mountain tribes of Urartu and its associates of Mannai and Madai in the north, who had been able to push their frontier to within less than a hundred miles of Nineveh. The consciousness of weakness and possible defeat would go far to explain the readiness of Nineveh to accept the prophet’s message.

Until the nineteenth century, Jonah was regarded as history. Liberal scholars today largely contend that the book is no more than a beautiful allegory or parable. Our Lord, however, referred to the story of Jonah as historical (Mt 12:38–41; Lk 11:29–30, 32). The main argument against the historicity of the book is, of course, the alleged impossibility of Jonah’s surviving three days and three nights in the belly of the fish (1:17). There are sufficient, well-attested occurrences to show that survival is possible under these circumstances. Jesus placed the incident alongside the greater miracle of his own resurrection.

2. Date and Authorship

The information in the book clearly must have come from Jonah himself in the eighth century B.C. Since he is nowhere claimed as author, and since he is constantly referred to in the third person, the possibility cannot be dismissed that its present form comes from another hand.

3. Purpose

The purpose of Jonah’s proclamation was to bring the Ninevites to repentance. The declaration of God’s loving care was made, not to Nineveh, but to Jonah (4:11), and so to Israel. Taking the book as a whole, it is a revelation to God’s people of God’s all-sovereign power and care. It had a special relevance to Israel over which the shadow of Assyria was falling, and later to Judah, as it faced destruction at the hands of Babylon.

Nineveh and Tarshish represented opposite ends. of the Levantine commercial sphere in ancient times. The story of Jonah extends to the boundaries of OT geographic knowledge and provides a rare glimpse of seafaring life in the Iron Age. Inscriptions and pottery from Spain demonstrate that Phoenician trade linked the far distant ends pf the Mediterranean, perhaps as early as the 12th century B.C.

© 1985 The Zondervan Corporation

EXPOSITION

I. The Disobedient Prophet (1:1–2:10)

A. Jonah’s Flight (1:1–3)

1 There is no indication how God communicated his will to Jonah. In many cases there must have been the overwhelming certainty of the divine message without any consciousness of how it had come. “Jonah son of Amittai” is the only prophetic name recorded for the North in the nearly forty years between the death of Elisha and the ministry of Amos (2Ki 14:25). Later rabbinic tradition claimed that Jonah was the widow’s son brought back to life by Elijah (1Ki 17:17–24). So far as we know, Jonah was not picked because he was particularly suited to the task. When he fled, God could have turned to someone else; but since it is the sovereignty of God that is being particularly stressed, God held to his choice (cf. 1Co 9:16).

2 “The great city of Nineveh” goes back to early days after the Flood (Ge 10:11). Though it was not always the capital city of Assyria, Nineveh was always one of its principal towns. In the light of 4:11, it might be better to translate “great [GK 1524] city” as “big city”; for it is the number of its inhabitants that is being stressed. “Preach against it” indicates that God was particularly concerned with the Assyrians’ self-confident pride (Isa 10:13) and cruelty (Na 3:1, 10, 19).

3 Apparently “Tarshish” comes from a Semitic root meaning “to smelt”; since there were a number of places with this name on the Mediterranean coast, probably Tartessus in Spain is intended. We need not go beyond Jonah’s own words (4:2) to find his motive for not wanting to go to Nineveh, but this does not explain why he tried to run away.

Israel was involved in the battle of Qarqar in 853 B.C. and under Jehu paid tribute to Assyria in 841 B.C. If Assyria were to be spared now, it could only be that the doom pronounced at Horeb to Elijah (1Ki 19:15–18) should go into full effect. Sick at heart from the foreshortened view of the future, so common to the prophets in foretelling the coming judgments of God, Jonah wished to escape, not beyond the power of God, but away from the stage on which God was working out his purposes and judgments. “To flee from the Lord” is here probably the equivalent of “to flee from the Lord’s land.”

B. The Storm (1:4–6)

4 For the ancient Near East, the gods had created order by defeating the powers of chaos; but these had been tamed, not abolished, and so remained a constant threat. The embodiment of these lawless and chaotic forces was the sea, which people could not control or tame. Frequently God’s control of the sea is used to stress his complete lordship over creation (cf. Pss 24:2; 33:7; 65:7; 74:13; et al.).

5–6 The crew were probably all Phoenicians, whose language differed only slightly from Jonah’s; so the crew would have shared in a common religion and pantheon. In a developed polytheism, however, individuals tended to concentrate on favorite deities; in addition, all sorts of attractive foreign deities tended to be adopted by sailors.

Possibly Jonah’s hurried flight to Joppa played a part in his sound sleep. The storm that can terrify the sailor can reduce the landsman to physical impotence and unconsciousness, as indeed “deep sleep” suggests. The captain’s command to Jonah that he pray reflects the heathen concept that the amount of prayer is of importance (Mt 6:7) as well as that polytheists could seldom be sure which god had been displeased.

C. Jonah’s Responsibility (1:7–10)

7 “Come, let us cast lots” assumes that Jonah had joined in the chorus of prayer. Though Jonah may have been terrified, he would hardly have realized, as did the sailors, that anything exceptional was happening. The lack of result from prayer and the rarity of such storms in the sailing season (cf. Ac 27:9) made the sailors conclude that someone on board must be responsible for their plight.

8 With the generosity of men who constantly risked their lives in their daily work, the sailors wanted to know whether Jonah was one who fully deserved his fate (cf. Ac 28:4), or whether there were extenuating circumstances that would justify their taking risks to try to save him.

9–10 In saying “I am a Hebrew,” Jonah used the term by which an Israelite was known to his neighbors. In a polytheistic society, it was difficult to find a title that would more perfectly express the supremacy of the Lord than “the God of heaven.” What terrified the sailors was the addition of “who made the sea and the land.” They knew that Jonah was running away from the Lord (v.10), whom they knew to be the God of Israel. As Phoenicians they did not take seriously Jonah’s claim that his Lord was superior to Baal. But now Jonah had claimed that the Lord was the Creator of the sea. Terrified they said, “What have you done!” It is an exclamation, not a question.

D. Jonah’s Rejection (1:11–16)

11 The sailors found themselves in a new and unexpected position. They realized that they were not dealing with a heinous criminal. Here was a god’s servant who had fallen out with his lord. In a culture where correct procedure in the service of the gods was essential, they sought to do the will of the Lord correctly. Only Jonah could guide them.

12 Jonah’s answer to the distraught sailors was, in essence, “Hand me over to my God.” Once the lot pointed to Jonah, he accepted that the storm was not simply a “natural phenomenon.” So Jonah was willing to be handed over to his God. Jonah knew that God would not make the sailors pay for what had been an innocent act on their part. Jonah was confident that the sea would calm down once he was no longer in the ship.

13–14 Since the sailors’ religious outlook could make no sense of a god of heaven’s creating and controlling the sea—they probably did not even think of the sea as created but rather as a remnant of the original chaos—to throw Jonah overboard was equivalent to murdering him. They could not know for certain whether they were doing the Lord’s will, and they feared that he might punish them for the death of his servant. So they tried hard to set him ashore, even though it involved great risk to the ship. When the increasing storm made this impossible, they prayed that they should not be held guilty of Jonah’s death; for clearly the Lord had done as he pleased. When they called Jonah “innocent” (GK 5929), they were not impugning God’s actions; they were merely stating that no human tribunal had passed sentence on him.

15–16 So far as the sailors knew, Jonah had been dealt with by his angry god. The immediate cessation of the storm after they threw Jonah overboard showed them that the Lord really had control of the sea. So “they offered a sacrifice to the Lord and made vows to him.” There was a new respect for the God of Israel, a new understanding of his power. Because Jonah believed in the sovereignty of God, the sailors were brought to a realization of his power. But there is no evidence that their spiritual apprehension went further.

E. Jonah’s Protection (1:17–2:1)

17 The sea did not change its nature when Jonah splashed into it. Jonah did not suddenly develop into a champion swimmer. But the necessary protection was there. There is no suggestion that the fish was a special creation for the purpose or that Jonah’s preservation within it was miraculous. The power of God ensured that the fish was there at exactly the right time.

Why did God choose this means of preserving Jonah’s life? God could easily have provided a piece of floating wreckage to which Jonah could have clung, until he washed up on the beach half-drowned. Miracle is not the gratuitous display of God’s omnipotence, nor is it called out merely because of human need. Taken in its setting, it is probable that every miracle has spiritual significance (cf. the word “sign” in John’s gospel). That must surely be the case here, especially since Jesus used this miracle to picture his own resurrection.

For the sailors the raising of the storm and its subsequent quieting were indubitable evidence of the Lord’s control of chaos. Since “the fish” was at God’s disposal, it meant that every force in the world, however potentially dangerous, was completely under God’s dominance and control. So while in one way the fish is secondary in the revelation to Jonah, it was needed for the prophet to grasp that God’s love is operative in a world that is entirely under divine control.

Once Jonah was on dry land again, he could make some kind of estimate of how long he had been in the fish. Yet to make any exact measure of the number of hours would have been impossible for him. Roused suddenly from a deep slumber, stupefied by the violence of the storm, and in all probability seasick, Jonah would have been in no position to know at what hour he was thrown overboard. Furthermore, on reaching the shore he would have needed time to collect his wits. Clearly, then, the term “three days and three nights” is intended as an approximation, not a precise period of seventy-two hours. The use by Jesus (Mt 12:40) should almost certainly be understood in the same way.

2:1 The popular idea that Jonah went straight from the deck of the ship into the fish’s open mouth has no support from either the narrative or Jonah’s prayer. He was half-drowned before he was swallowed. If he was still conscious, sheer dread would have caused him to faint—there is no mention of the fish in his prayer. He can hardly have known what caused the change from wet darkness to an even greater dry darkness. When he did regain consciousness, it would have taken some time to realize that the all-enveloping darkness was not that of Sheol (see next comment) but of a mysterious safety.

F. Jonah’s Psalm of Thanksgiving (2:2–9)

2–4 “From the depths of the grave” is literally “from the belly of Sheol [GK 8619].” True, Sheol is often no more than a synonym for the grave; Jonah was not saying, however, that he thought he was buried but that he had gone to join the dead. The terrifying experience brought him to the realization of his plight and elicited the confession: “Yet I will look again.” This is not a statement of salvation but of Jonah’s determination to pray in spite of his banishment.

5–6 Jonah continued the description of his downward plunge into the deep, vividly illustrating the hopelessness of his situation. He was, as it were, beyond human help. The reference to the place of the dead as “the pit” (GK 8846) points to Jonah’s expectation of certain death.

7–9 As he plummeted through the waters, Jonah realized that “his life was ebbing away.” In these fleeting moments his thought turned to the Lord and his “holy temple.” Remarkably, in spite of the position in which he found himself, Jonah had a mental picture of the despairing sailors calling in vain on their gods, while he, whom they thought had been lost, was awaiting the demonstration of his God’s salvation.

G. Jonah’s Deliverance (2:10)

10 The literal Hebrew reads, “And the LORD spoke to the fish.” Unlike the prophet, the fish responded promptly, as soon as it knew God’s will. Where the fish spewed out Jonah is not indicated. No doubt the effect of the fish’s gastric juices on Jonah’s face and other exposed parts of his body must have been terrible.

II. The Obedient Prophet (3:1–4:11)

A. Jonah’s Proclamation (3:1–4)

1 The expression “a second time” is completely vague. There are many examples in the Scriptures of no second chance. Indeed, we should rather ask why the second call came to Jonah. The answer seems to be the sovereignty of God, one of the main themes of this book.

2 God does not lay weight on Nineveh’s political importance or on the magnificence of its buildings. “The message I give you” does not necessarily suggest that Jonah would have said otherwise. It is merely one more indication that we are dealing with the sovereignty of God.

3 “Now Nineveh was a very large city” (NIV note) most probably is the correct reading. “An important city” does not suit the context and introduces a note of particularity into a book where universality is constantly being implied. The stress on the importance and size of Nineveh is entirely justified. Its population was at least 120,000 (4:10), while Samaria, almost certainly larger than Jerusalem, had about 30,000.

“A visit required three days” is literally “a distance of three days.” This could mean that it took three days to go either across it or around it; but it certainly does not mean what the NIV rendering might be taken to imply, that it would take three days to visit every part of it. Modern archaeology has shown that the inner wall had a length of almost eight miles.

4 Jonah was not necessarily proclaiming God’s message as he went into the city. But sometime “on the first day,” Jonah “proclaimed” his message. There may well have been something about Jonah, his bearing, his dress, or his “gastric juice tan” from the fish’s belly as he strode toward the center of the city, looking neither to the right nor to the left, that drew many after him. When he finally stood and shouted, “Forty more days and Nineveh will be destroyed,” the news spread like wildfire. The credibility of the message was underscored by the fact that at the time Assyria stood in considerable danger from its northern neighbors. But the word of the Lord worked the miracle, not Jonah or his commentary.

B. Nineveh’s Repentance (3:5–10)

There now begins a subtle interplay on the two divine names. Up to this point, we consistently find the name “the LORD” (Yahweh; GK 3378), i.e., the name of the covenant-making God of Israel. Now alongside it we find the name “God” (Elohim; GK 466), the all-powerful One, the Creator, the Lord of nature. The obvious purpose is to bring home that Jonah had not been proclaiming the Lord to those who did not know him but that the supreme God, whatever his name, was about to show his power in judgment. There is not the slightest indication that Jonah had mentioned the God of Israel or had said that he came in his name. The Ninevites, however, recognized the voice of the supreme God, whatever name they may have given him, and repented.

5 We must picture the people, both those who heard Jonah and those to whom his words were reported, as saying spontaneously, “Let us fast!” Sackcloth was a standard, virtually obligatory, accompaniment of fasting. The coarsest of cloth, often made of goat’s hair, sackcloth was the normal dress of the poor, prisoners, and slaves; it was worn by those who mourned (Eze 7:18). Prophets wore it, partly to associate themselves with the poor, partly perhaps as a sign of mourning for the sins of the people. When used by the Ninevites, it expressed their complete inability to contend with the divine decree and with the recognition that they were the slaves of the supreme God.

6 There is no suggestion that Jonah made any effort to reach the royal presence; hence the news would have reached the king later than it did many of his subjects. He not only came down from his throne and sat on the ground—a feature of mourning rites—dressed in sackcloth like the meanest slave, but he sat in the dust, which means, presumably, in the open air, where he could be seen by his subjects. All this was done completely spontaneously. Then came the realization that this concerned everyone, and the decree was issued (v.7).

7 The king’s courtiers and counselors sat in the dust around him and rapidly agreed on a decree that made the spontaneous response official. With the mourners were to be linked the domestic animals, a touch suggesting that it was indeed “Greater Nineveh” that was involved. Though we have no records from Mesopotamia of animals being so involved in mourning rites, there is nothing alien to the Oriental mind in it.

8 Anything and everything condemned by law and conscience is included under “evil ways.” “Violence” (GK 2805) means a defiance of the law by one too strong to be brought to account. The Assyrians assumed that in virtue of their conquests they had been placed above lesser breeds and were entitled to ignore the dictates of conscience and compassion in their behavior to their neighbors. It is easy to slip into the concept that our position gives us the right to dominate others.

9–10 The operative phrase in these two verses is that God “had compassion” (GK 5714). We can know the character of God only from what he does and the words he uses to explain his actions. When he does not do what he said he would, we as finite beings can say only that he has changed his mind or repented, even though we should recognize, as Jonah did (4:2), that he had intended or desired this all along. “Compassion” is an inadequate rendering because it does not bring out the concept of a change. Thus “relent” is better. God’s change was due to the change in the Ninevites.

2. Jonah’s Displeasure (4:1–4)

1 We are so obsessed with pure doctrine that we are not satisfied when we meet obvious repentance but seek to ensure that it is accompanied by right doctrine. Jonah knew God well enough to understand that the person who really was repentant would be justified in God’s sight. The literal translation here is “But it was evil to Jonah with great evil.” The term “evil” (GK 8288 & 8317), which has been repeatedly applied to the Ninevites, now characterizes the prophet. By objecting to the character and actions of God, Jonah has effectively put himself out of fellowship with God, just like the evil and ignorant heathen. But God showed him the same compassion as he had shown Nineveh.

Why was Jonah so angry? Rabbinic literature suggests that on the basis of Dt 18:21–22 he would be regarded as a false prophet. True enough, once the first wave of terror had passed and destruction did not come, many in Nineveh must have asked themselves whether Jonah had really been a messenger of the gods. That was an unavoidable result of divine mercy. But it was recognized universally that a pronouncement of divine punishment might be averted by suitable penitence. Prophecy is conditional. So even if this motive played a part in Jonah’s thinking, it must have been a minor one; and it does not explain why he ran away.

2 Jonah told God exactly why he was angry. He objected to God’s sparing Nineveh. Jonah’s motive could only stem from what Nineveh had meant in Israel’s past and what he expected it to be in the future. (Compare the exultation over its fall in Na 2–3.)

The word “gracious” (GK 2843) is linked with “grace” and expresses God’s attitude toward those who have no claim on him, since they are outside any and every covenant relationship. The Hebrew term translated “compassionate” (GK 8157) came to be linked with the word for “womb” and expressed the understanding and loving compassion of the mother to her child. We have here the male and female aspects of understanding, compassion, and favor united in the one God. “Love” (hesed; GK 2876) expresses God’s behavior in the covenant relationship. There is no one term in English that adequately expresses the wide and rich range of meaning of this word. What is clear is that Jonah was finding fault with God as he really is, not as he imagined him to be.

3 There can be little doubt that when Jonah asked God to take away his life, there is much more in what Jonah said than lies on the surface. He was virtually saying to God, “I have devoted my life to your service as your servant, as your prophet. But what I have experienced of you just does not make sense of the world order in which I find myself. Why should I go on living? For to leave your service would make my life purposeless. Once, in the past, you showed Elijah that there was a deeper purpose in life than he realized [1Ki 19:4]. Have you perhaps a similar message for me?”

4 “Are you right to be angry?” is a better translation than “Have you any right to be angry?” God was not rebuking Jonah; God was not even asking him what right he, a man, had to criticize God. Rather, he was suggesting to him that he might not be correct in his estimate of the position. Scripture has many examples of people who in agony tried to understand the ways of God and used language that others might consider blasphemous (cf. Jer 15:15–18; 20:7–18). God shows his compassion with all such people, including Jonah.

4. God’s Rebuke of Jonah (4:5–9)

5 The usual view is that Jonah, hoping against hope, was waiting to see whether God might not change his mind again. But unless we are prepared to maintain that Jonah thought that Nineveh’s repentance was merely superficial and transient and that therefore God might change his mind, the traditional view is alien to the picture of the prophet we have been slowly building up. It is far more probable that Jonah was expecting something to happen that would explain God’s ways with humankind a little more clearly to him.

6 In the rest of this section, the divine name Elohim (“God”), which has been used consistently for God’s dealings with Nineveh, is now used for his dealings with Jonah. The use of “LORD God” (Yahweh Elohim; see comment on 3:5–10) forms a link between the two usages, linking the God of creation (cf. Ge 1) and the God of revelation (cf. Ex 4). The Palestinian Jewish tradition identified the word traditionally rendered “gourd” with the castor oil plant. “Vine” is a safe rendering of this word. Though not stated, it is clear that the action Jonah took to “ease his discomfort” occurred in the hot season, when the daily maximum temperature in Mesopotamia is about 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

7 The repeated use of the verb “appointed” (GK 4948) of the fish (1:17), the vine (4:6), the worm (4:7), and the wind (4:8) stresses the divine initiative. The word for “worm” (GK 9357) implies something small. God uses both the great fish and the insignificant worm equally as instruments of his purpose.

8 “A scorching east wind” is normally called a “sirocco,” which means “east wind.” Obviously such a wind, blowing in from across the desert, withers all green growth. For Jonah there was no shelter, unless he was willing to reenter Nineveh. The shelter he had built did not exclude the wind and only partially broke the force of the sun’s rays. Completely dispirited he in essence said, “I would be better off dead than alive.”

9 As in v.4, it would be better to translate God’s question by “Are you right to be angry about the vine?” and Jonah’s answer by “I am.” Why was Jonah so angry, or why did he feel such grief for the withered vine? God’s answer in v.10 suggests that we take “Jonah was very happy about the vine” (v.6) to mean that sitting there in the burnt-up Tigris plain, shimmering in the heat, Jonah had felt real joy in the sight of the fresh, green plant. True enough, it increased his comfort, but that was secondary.

5. God’s Mercy (4:10–11)

10 One of the greatest dangers besetting human beings is that they become such a part of their environment that they miss the pathos that pervades the universe. Paul describes it as a “groaning as in the pains of childbirth” (Ro 8:22), which comes from the futility caused by its bondage to decay. Jonah had apparently grown completely indifferent to the fate of God’s creation outside Israel. We need hardly be surprised, for this attitude has been common within the church, and indeed within some small local churches. So God placed his prophet on the level of an ordinary person. The discomforts of the summer heat, the attractiveness of the vine, and the destructiveness of the sirocco had nothing to do with Jonah’s theology. He reacted to them as an ordinary man in the setting of nature.

Again the narrative changes to “the LORD.” Once Jonah had realized his link with the rest of God’s creation, God could declare the link between himself, the Creator, and his creation—not only humankind, made in the image and likeness of God, but also animals.

11 The meaning of “more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left” is difficult. It could refer either to the whole population of Nineveh or to the small children who do not yet know their right hand from their left. The former has been supported by archaeological considerations, which set the maximum population of Nineveh at 175,000 or less. Thus if only children were intended, far too high a total population would be involved—even if “Greater Nineveh” (cf. 3:25–3) is included.

We do not find in Scripture the sentimentalism about animals found in many classes of society today. Even so, Jonah had to understand that the fulfillment of his wishes about Nineveh would have involved the destruction not only of innocent human beings but also of “many cattle as well” that were dependent on people.

The curtain falls, and we are not told what, finally, Jonah did or said. Quite simply, the book contains a revelation of God’s character and attitude toward his creation given to Jonah and through Jonah to Israel and to us. For Christians, the Son of Man’s three days and three nights in the heart of the earth assure us of a love that embraces all, even in the darkest hour. We know that in Christ, God was reconciling the world to himself (2Co 5:18–19), and we will look with new eyes on those who have been reconciled. Christians cannot regard as enemies those whom God refuses to regard as his enemies.

The Old Testament in the New

| OT Text | NT Text | Subject |

| Jnh 1:17 | Mt 12:40 | Three days and nights |