INTRODUCTION

1. Background

The setting of Nahum’s prophecy is the long and painful oppression of Israel by Assyria and the divine prospect of its end. Although God was the ultimate author of Israel’s affliction, Assyria, the rod of God’s anger, was the agent of his wrath; and the cup in the Lord’s right hand was now coming around to her.

Assyria had long been central in God’s affliction of his people, Israel. As early as the ninth century, Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.) exacted tribute from Jehu in one of his western campaigns (c. 824). However, Tiglath-pileser III (745–727) represents the first major scourge of Israel. He invaded that land during the reign of Menahem (752–732; cf. 2Ki 15:29; 1Ch 5:6, 26). This king extended his authority into Judah, where Ahaz (735–715) pursued a policy of submission to Assyria, thereby incurring the opposition of both Pekah, king of Israel (c. 740–732), who favored the anti-Assyrian coalition of his predecessor Ahab, and Isaiah, who denounced his faithlessness in depending on Assyria rather than on the Lord, when faced with Pekah’s aggression (2Ki 16:5–18; 2Ch 28:16–25; Isa 7:1–25; 8:6–8). During Ahaz’s reign, therefore, Judah was faced with the issue of submission or resistance to Assyria—an issue that confronted the nation for over a century and to which it responded in faith or fear according to its relationship to the Lord. Pekah was murdered by Hoshea (732–722), who adopted a vacillating pro-Assyrian policy. His fickle decision to rely on Egypt and repudiate his allegiance to Assyria provoked the invasion of Shalmaneser V (727–722), Tiglath-pileser III’s successor.

Samaria fell after a long siege by Shalmaneser and his successor, Sargon II (721–705); the northern kingdom was destroyed and its population deported (2Ki 17:3–6). This catastrophe is explicitly attributed to the Lord’s affliction of Israel for her sin (2Ki 17:20), as were the misfortunes of Ahaz in the same era (2Ch 28:19–20). Palestine experienced further depredations under Sargon II (Isa 20:1–6), before facing the full brunt of Assyria’s hostility in the reign of Sennacherib (704–681). Hezekiah (728–687) had succeeded Ahaz and had abandoned Ahaz’s pro-Assyrian policy (2Ki 18:7–8, 19–20). Sennacherib thereupon invaded Judah (701), conquered its fortified cities, and threatened Jerusalem, before the decimation of his army by a “wasting disease upon his sturdy warriors” (Isa 10:16; cf. 2Ki 18:13–19:37; 2Ch 32:1–31; Isa 36:1–37:38). The terrible distress preceding this deliverance was the Lord’s chastening of his unfaithful yet beloved people (cf. Isa 5:26; 10:5–6, 11–12, 24–25; et al.).

The nation of Nineveh continued for another century, having times of both political stability and instability. Finally, as the power of Babylon began to climb during the reign of Nabopolassar (625–605), the Assyrian Empire began to crumble, and in 612 the siege and destruction of Nineveh were completed.

2. Authorship and Date

Little is known about Nahum himself. According to 1:1, he is “the Elkoshite.” An Arab tradition places this village near Mosul in modern Iraq. Ancient writers, however, understood the prophet’s home to be somewhere in Galilee.

From internal data it is possible to date the major blocks of material in Nahum. As a message of judgment, the book makes no sense if it was proclaimed following the collapse of the Assyrian empire in 612 B.C. On the other hand, references to the destruction of Thebes (No Amon) by the Nile (3:8) demand that the prophecy postdate that city’s fall to Ashurbanipal in 663 B.C. Further consideration of the still formidable state of Assyrian power reflected in the book requires a date prior to the decline of that kingdom after about 626 B.C.

3. Theological Values

Theologically Nahum stands as an eloquent testimony to the particularity of God’s justice and salvation. To the suffering remnant, there was little question that God would and did punish his own covenant people; but whether he was equally able and willing to impart justice to the powerful heathen nations surrounding Israel was untested. Among those nations, none was more cruel and arrogant than Assyria. The severity and kindness of God were both under scrutiny: the former as to whether it applied only selectively to his own people, and the latter in the context of God’s ability and desire to bring about ultimate salvation for those who were faithful to him.

Into the situation of Israel’s apostasy, Judah’s vacillation, and Assyria’s might came the word of the Lord: “The LORD is a jealous and avenging God . . . slow to anger and great in power; the LORD will not leave the guilty unpunished” (1:2–3). The vivid imagery of Nineveh’s demise is eloquent testimony to the power of a God whose strength is never simply an abstraction. A theology of divine sovereignty and justice, applauded by all the nations, emerges from the specifics of Assyria’s fall.

It is not merely divine retribution, however, that emerges from the picture. There is also good news to proclaim (1:15). Judah is called to celebration when the day of the Lord’s wrath is fully understood and the remnant is prepared in righteousness. The corollary to the severity of God is his kindness, a mercy that includes covenant keeping and justice.

When the forces opposing God are so firmly ensconced and the flickering lamp of God’s people is at the point of extinction, Nahum reminds us, as do the ruins of ancient Nineveh, that God himself is the ultimate Ruler. He will have the final word.

EXPOSITION

I. The Anger of the Lord (1:1–15)

A. The Judgment of the Lord (1:1–11)

The opening verses of Nahum form a prologue dominated by the revelation of God’s eternal power and divine nature in creation (cf. Ro 1:20). This revelation is characterized preeminently by God’s justice, expressed in retribution (v.2) and wrath (vv.2–3) that shake the entire creation (vv.3–6). The mercy of God, for all its reality, is a fleeting counterpart of this awesome display of majesty.

1. Awesome in power (1:1–6)

1–2 The adjective “jealous” (GK 7868) is used solely of God, primarily in his self-revelation at Sinai (Ex 20:5; 34:14). Against this covenantal background, it denotes the Lord’s deep, fiercely protective commitment to his people and his exclusive claim to obedience and reciprocal commitment. Where this relationship of mutual commitment is threatened, either by Israel’s unfaithfulness or by foreign oppression, the inevitable expressions of such jealousy are “vengeance” and “wrath,” directed to restoring that relationship.

“Avenging” and “vengeance” (both GK 5933) are judicial in nature, expressing judgment and requital for infractions of law and morality, primarily those committed with presumption and impenitence. As a judicial function “vengeance” belongs supremely to God, the Judge of the whole earth, and to the ordained representatives of his authority. Consequently, human beings are forbidden to take the law into their own hands. Nineveh—despite God’s use of her violence—had done just that. Now, just as she had devastated cities and populations, so it would happen to her. She had sown the wind and in her impenitence would surely reap the whirlwind.

Like jealousy, “wrath” (GK 5757) denotes intense and passionate feeling. It constitutes a divine characteristic that human beings must face whenever they break the proper limits of their relationship to God; to deny God’s “wrath” is to deny the reality of judgment and the necessity of atonement. Verse 2 lays a foundation for the entire prophecy; all that follows is rooted in this revelation of the justice and burning zeal of the Lord exercised on behalf of his people.

3 The Lord’s anger is balanced by his forbearance, which represents a restraint born of meekness and not of weakness; it is not to be misunderstood as passivity. Nor is it exercised indefinitely, for his power assures that “he will not leave the guilty unpunished.” The forbearance of God had been extended to Nineveh a century earlier in response to her repentance (Jnh 3:10); but it was forfeited by her subsequent history of ruthless evil, making way for God’s judgment instead.

The power and majesty of God are evidenced most dramatically in the forces of nature. “Whirlwind” and “storm” are often expressions of his judgment (cf. Ps 83:15; Isa 29:6). For all their grandeur, these mighty forces are dwarfed in the presence of the Lord, whom the highest heavens cannot contain; the tempest is but the disturbance caused as he marches by, and the dark storm clouds are merely dust stirred up by his feet.

4 The preceding description of the Lord’s power is extended in the image of drought, consuming the fertile highlands of Palestine and their sources of water. “Bashan” in Transjordan, “Carmel” in northern Israel, and the “Lebanon” range on Israel’s northern frontier are frequently represented together as the choicest forest and pasture regions of the Promised Land. Nevertheless, all are revealed as vulnerable; like the pride and strength of humankind, they are devastated and “wither” before the burning anger of the Lord. The drought depicted here is abnormally severe in its catastrophic effects on “sea” and “rivers.”

5 Earthquake forms a third biblical manifestation of the Lord’s power, causing the hills to “melt away.” Such melting may be brought on by intense heat, a phenomenon associated with the earthquake at Sinai to which vv.2–3 allude. However, the verb “melt away” may also be applied to the effect of flooding.

6 This verse emphatically recapitulates the concept of anger, repeating the noun “wrath” that is stressed further by the kindred terms “indignation” and “fierce anger,” and again describing the irresistible manifestation of this anger, before which the entire created world is subdued. This wrath is poured out “like fire”—fire is a common expression of the Lord’s judgment. The section concluding with v.6 is deeply imbued with the recollection of God’s covenant with Israel, also sharing with numerous poetic passages their various images of divine judgment and power (cf. Pss 11:6; 18:7–15; 29:3–9; Jer 23:29; Eze 38:19–22; Joel 2:1–11; et al.).

2. Just in execution (1:7–11)

7 The goodness of God forms a basic tenet of Israel’s faith. Also, it repeatedly forms the basis for human faith, expressed in trusting obedience; where the goodness of God is impugned with success, faith soon crumbles. As an expression of covenant commitment to defend his people, the Lord himself is a “refuge” (GK 5057) or stronghold of protection. He “cares for” (lit., “knows”; GK 3359) the faithful, acknowledging their relationship to him and their claim on his goodness inherent in that relationship. The “trouble” from which he gives protection is graphically illustrated in Judah’s sufferings at the hands of Assyria. It demanded a “trust” that was too often misplaced.

8 The goodness of God, like his patience, does not obviate his judgment, which is directed against those who refuse to submit to his rule, i.e., “his foes” and the oppressors of his loyal people. As long as evil exists, God’s judgment, expressed here in terms of “flood” (cf. v.3; 2:6), is an inevitable expression of his goodness on behalf of the victims of evil; it banishes the enemy into “darkness” (i.e., death).

9 The utter finality of this sentence is stressed by “bring to an end.” It is reinforced by the terse ambiguity of the final line: “trouble” will not arise again for God’s people, for it will descend on those who trouble Israel in so conclusive a way that it need not arise again. The crime of these enemies is premeditated antagonism: they do not stumble into sin but actively “plot” against the Lord.

10 The means of judgment is portrayed here in metaphorical language. “Thorns” describes the spiny or prickly vegetation that proliferated in the semiarid climate of Palestine. They often grew as a tangled, impenetrable mass; as such, they were good for little more than burning. The Assyrians are portrayed as being “entangled among” or like such thorns, to which they correspond both in their worthless character and in their merited destruction.

The image of drunkenness reiterates these varied associations: a drunkard is good for nothing useful, and drunkenness is both a cause and consequence of judgment. The keynote of both lines, however, is helplessness. A drunkard is incapacitated from defending himself; the Assyrians would be no less vulnerable before the wrath of God.

Like thorns, stubble is without intrinsic value and is subject to be burnt; being “dry,” it is an easy prey for the flames by which it is “consumed.” Nineveh’s destruction by fire is rooted in her helplessness to avert the disaster; and this in turn is due to her decadence, characterized by drunkenness.

11 The enemy is again defined as one who “plots” against the Lord, being specified further as a distinct individual from whom the rebellion emanates; such an individual is identified clearly in 3:18 as the “king of Assyria.” The ruler envisaged here emerged from Nineveh in his opposition to the Lord. Sennacherib stands out as the most powerful aggressor to emerge from Nineveh against Judah. According to the Assyrian annals describing his Judean campaign (c. 701), he cruelly devastated forty-seven fortified cities including Lachish. That Nahum was referring primarily to Sennacherib’s invasion is supported by his repeated reminiscences of Isaiah’s prophecies relating to that era.

The intent of this plotting is “wickedness” (GK 1175), a noun often translated as “worthlessness” and implying a total lack of moral fiber and principle (e.g., Dt 13:13).

B. The Sentence of the Lord (1:12–14)

12 The opening clause of this verse is typical of the formula by which a messenger received or transmitted a message from his lord. The present decree is addressed to Judah and is essentially an oracle of salvation; it incorporates an announcement of judgment that is addressed directly to Assyria (v.14). The decree reverses the fortunes of the Assyrians. Although they had “allies,” they would be “cut off.” Although “numerous,” the Assyrians would “pass away.”

A similar reversal is decreed for Judah. To be “afflicted” (GK 6700) is to be humbled and oppressed. Such affliction is repeatedly the agent of God’s chastisement, frequently being administered to his own people at the hands of foreign nations.

13 The continuing existence of such servitude is implied by the emphatic “Now” and by the future orientation of the promised deliverance from the “yoke” and the “shackles.” This further supports dating Nahum’s prophecy before Josiah’s reign. Despite the devious and tragic analogy of the northern kingdom, the southern kingdom was still to experience political and religious revival in the reign of Josiah. And though its sins had made exile inevitable, this did not occur at Assyrian hands. The breaking of Assyria’s yoke is strikingly affirmed by Nabopolassar, who was an unwitting instrument of the Lord’s purposes (cf. Isa 45:4–5).

14 The “name” (GK 9005) of a population represented its living identity, perpetuated in its “descendants.” The root underlying “descendants” (GK 2445) is used of physical and particularly dynastic succession. Thus Nahum implies the eradication of Nineveh’s dynastic rule and of the nation whose cohesion derived from the Neo-Assyrian monarchy now centered at Nineveh. Nineveh’s consignment to the grave reiterates the certainty of this extinction. This judgment is rooted in the charge that the city, for all its regal and religious grandeur, is “vile.”

The Assyrian kings claimed to rule by the favor and authority of their “gods,” whom they honored accordingly. Ashurbanipal, on a single cylinder, paid profuse homage to seventeen of the principal gods of the Assyrian pantheon. The judgment of Nineveh’s king therefore demanded the destruction of the idolatrous religion on which his authority was founded. This was centralized in the “temple,” which housed the “carved images” and “cast idols.” These idols were normally made of precious wood plated with gold or of molten metal. The utter inefficacy of such “gods” was thus to be exposed in the destruction of their place of residence that they were powerless to protect.

C. The Purpose of the Lord (1:15)

15 The proclamation of “peace” (shalom; GK 8934) is replete with the promise of God’s redemption and constitutes the most precise correlation of Nahum with Isaiah (e.g., Isa 9:6–7; 32:17; 53:5; et al.). The picture is one of joyous and complete restoration of the Lord’s people and their legitimate worship. The reversal of fortunes is thus completed as Nineveh’s flourishing religion is to be buried and the worship of oppressed Judah resurrected. The anticipated renewal of vital worship was accomplished in the reign of Josiah, after about 631 (2Ki 22:3–23:27; 2Ch 34–35).

As in Hezekiah’s reign, this assertion of religious independence demanded that the “wicked” who opposed it be “destroyed.” The verb “destroy” (GK 4162) is commonly used of cutting down an enemy in battle or of “cutting off” the name of the rebellious. The verb “invade” is similarly used of warfare.

II. The Fall of Nineveh (2:1–3:19)

The judgment of God decreed in ch. 1 is now worked out with terrifying actuality. Nahum 2:1–2 is transitional. On the one hand, it extends the dual perspective of judgment and mercy evident in 1:2–15. On the other hand, the military language and urgent imperatives of v.1 clearly anticipate the following battle.

A. Warning and Promise (2:1–2)

1 Nineveh’s “attacker” (GK 7046) is more literally a “scatterer,” a common figure for a victorious king (cf. Ps 68:1; Isa 24:1; Jer 52:8). In fulfillment of this prophecy, Nineveh was attacked in 614 B.C. by Cyaxares, king of the Medes (c. 625–585). A sector of the suburbs was captured, but the city was not yet taken. However, a subsequent alliance of Cyaxares with the Babylonian Nabopolassar led to their concerted attack on Nineveh in 612, a battle recorded in detail by the Babylonian Chronicle.

The Assyrians are mockingly called to action. Nineveh had in fact been well-equipped to withstand both siege and invasion. Sennacherib had spent no less than six years building his armory, which occupied a terraced area of forty acres. It was enlarged further by Esarhaddon and contained all the weaponry required for the extension and maintenance of the Assyrian empire. The royal “road” had been enlarged by Sennacherib to a breadth of seventy-eight feet, facilitating the movement of troops. However, the material resources would be of little avail if the “strength” (GK 3946) of the defenders could not be marshaled, and by the end of the seventh century it had been dissipated beyond retrieval.

2 This verse introduces the final reference to the salvation of God’s people, whose “splendor” he will “restore.” The noun “splendor” (GK 1454) implies elevation or exaltation. The comparison “like Israel” suggests restoration to the full stature promised to the nation and once occupied by it. The names “Jacob . . . Israel” are usually synonymous, and they came to denote the Twelve Tribes descended from Jacob. After the kingdom was divided in two, usage varies; but the names are more commonly applied to the northern kingdom. Following the destruction of Samaria, the southern prophets reclaimed these names (Isa 14:1–4; et al.). Evidently “Judah” is envisaged here, though possibly the resurrection of Israel as a whole is promised (cf. Isa 9:1–8; 11:10–16; et al.). Such restoration is necessitated by the devastation of the land’s “vines”—a mainstay of its economy, a source of its joy and fulfillment and indeed a symbol of the very life and identity of the nation. All this had been obliterated in the northern kingdom by the Assyrian “destroyers.”

B. Nineveh’s Destruction Detailed (2:3–3:19)

1. First description of Nineveh’s destruction (2:3–3:1)

a. Onslaught (2:3–5)

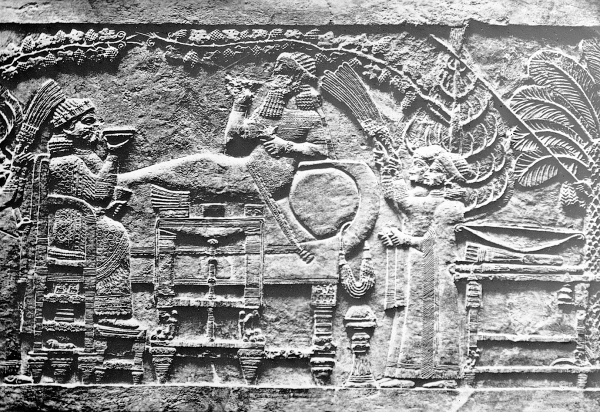

3–4 The antecedent of “his” appears to be the “attacker” of v.1. It is possible that the “Lord” (v.2) is also intended, summoning an enemy against Nineveh as he had summoned the Assyrians against Judah (Isa 5:26–30; 10:5–6, 15). The attack is led by the invader’s chariot forces, the most formidable wing of an army fighting in open terrain. The Neo-Assyrian “chariots” were built of various types of wood, for lightness and speed, with fittings of leather and of “metal” that would flash with reflected light. The chariots were fitted with a pole and yoke for the horses, normally a team of two, and with spoked wheels and a single axle. The Assyrian shields were either round or rectangular in shape, the latter being designed to cover most of the body. They were made of wood or wickerwork covered with leather, which could have been dyed “red.” It is evident from the parallel passage in 3:2–3 that cavalry accompanied the chariots, a typical feature of Assyrian warfare; and both “shields” and “spears” might also be carried by the infantry. The conflict was located in the “streets” of Nineveh, denoting its suburbs outside the inner defensive “wall” that had not yet been reached.

5 The “picked troops” represent the shock troops directed to breach the “wall.” The “protective covering” would describe the screen set up to protect them as they engaged in undermining and penetrating the wall. The stumbling of the “picked troops” is due, not to their weakness, but to the “corpses” of their victims, obstructing their advance.

b. Failing defenses (2:6–10)

6 This brief verse (five Heb. words) marks a decisive turning point in the campaign, as the main line of defense was broken and the heart of the city destroyed. The “river gates” envisaged are possibly those regulating the flow of water through the city. Indeed, the Akkadian term “gate of the river” was applied to a canal gate by Sennacherib. When “thrown open” by the enemy, who already controlled the suburbs where they were situated, the gates would have released a deluge of water, as a result of which the palace “collapses.”

7–8 The survivors are “exiled” amid the mourning of the “slave girls,” a not uncommon scene in Assyrian wall carvings depicting the agonies of their captives. The image of water depicts Nineveh’s fate with vivid irony. Nineveh was a place of watered parks and orchards. As at the Flood, however, “water” became a source of death, overflowing its boundaries and bringing chaos to the inundated city. Unlike the Flood, this “pool” promised no respite as its waters “drained away.”

9 The exaction of plunder had characterized the Neo-Assyrian Empire throughout its history. Those nations that submitted were drained of their resources, a fate suffered by Israel and Judah at various times. Thus Nineveh became the richest city throughout the ancient Near East. Now it was to suffer the same fate: its own people were to be led away; its “wealth” in “gold,” “silver,” and valuables was to be seized.

10 The defeat of the city is summarized forcefully. The inhabitants had failed to “brace” themselves (v.1) and instead “bodies tremble.” The verb underlying “tremble” (GK 2714) is often applied to labor pains.

c. An interpretive analogy (2:11–12)

11 The mocking rhetorical question introduces an extended metaphor that interprets the horror of the preceding verses: Nineveh has ravaged Mesopotamia like a savage beast of prey and must be judged accordingly. Nineveh’s kings compared themselves to lions in their terrible power, and its game parks sheltered such lions. Like a pride of such lions, Nineveh had been free to terrorize the land “with nothing to fear.” Now, however an accounting was due for that ruthless spirit.

12 The root of “killed” (GK 3271), recurring in the nouns “kill” and “prey,” is normally used of wild beasts that hunt and tear open their prey. The verb “strangle” (GK 2871) is equally apt to the image, as lions are represented as killing their prey in this manner in ancient Near Eastern art. Assyrian brutality matched and surpassed such displays of violence. The goal of the lion’s violence was prey “for his cubs”; as the lion filled its “lairs with the kill,” so Nineveh had been filled with foreign plunder.

d. Judgment from the Lord (2:13)

13 The climax is announced in the verdict of condemnation. “No prey” is a metonymy of effect: the taking of prey will be cut off with the extermination of the predator. The reference to “chariots” and to “messengers” recalls Sennacherib’s “evil,” plotted “against the Lord” (1:11; cf. Isa 37:9, 14, 24). This verse draws together the major motifs and vocabulary of Nahum’s prophecy: the Lord’s inexorable opposition to Nineveh; the destruction of its military resources; the role of “sword” and “fire” that “consume” the enemy; the cutting off of Nineveh and its “prey”; the termination of its cruelty, symbolized by the “young lions”; and the reversal of fortunes that awaits Assyria and Judah, exemplified in the fate of the “heralds.”

e. The verdict announced (3:1)

1 The relation of this verse to its context is rendered uncertain by the interjection “Woe.” Normally “woe” introduces a new section, suggesting here that v.1 belongs with 3:2–7. However, 3:1 is related thematically to 2:11–13 much more closely than to 3:4; it repeats the focal concept of killing in the noun “victims,” an association reinforced by the parallel nouns “plunder” and “blood.” And it also represents the city as “full (of plunder),” like the lion’s den (2:12).

2. Second description of Nineveh’s destruction (3:2–7)

a. Onslaught and failing defenses (3:2–3)

2–3 These verses resume the battle scene of 2:3–5, evoking the rapid movement and the sound of the onslaught led by the chariots. The term “cavalry” (GK 7305) may denote the mounted horsemen that are depicted accompanying chariots in Assyrian reliefs, or it may refer to the horses of the chariot corps. “Swords” were characteristic weapons of foot soldiers, being used in hand-to-hand combat; they did not form part of the regular equipment of horsemen or chariot crews. The “spears” also formed an integral part of the infantry’s weapons.

As in 2:3–10, the defenders are annihilated by the attack: four times—using three different words—the verse refers to the corpses left in the wake of the invading army. Possibly the “people stumbling” are the fugitives; in view of 2:5, they are more likely to be the victors, impeded by the sheer mass of bodies.

b. An interpretive analogy (3:4)

4 The root underlying the word “harlot” (GK 2390) occurs three times in this verse (cf. “wanton lust,” “prostitution”). The biblical references to “prostitution” imply treachery, infidelity, pollution, and lust. All are appropriate to this city that sacrificed any semblance of morality to personal interest. Of primary significance, however, is the prostitute’s motive of personal gain and the ominous “alluring” that she exercises to attain it. As Ahaz had been lured into unholy relations with Assyria formerly (cf. 2Ki 16:7–18), so Nineveh had drained the life of those enticed by her smooth ways.

The harlot’s practice of allurement and manipulation is abetted by “sorceries” and “witchcraft.” Both sorcery and harlotry suggest an illicit, surreptitious yet deadly means; they correspond to the stealth of the hunting lion and are equally destructive. Nineveh is here seen as using both immoral attractions (the city was a center of the cult of Ishtar—herself represented as a harlot) and sorcery (Assyrian society was dominated by magic arts) as a means to enslave others.

c. Judgment from the Lord (3:5–6)

5–6 As the Lord’s condemnation overthrows the city’s brutality (2:13), so it annuls the demonic power that promotes that brutality. The same principle of reversal is effected: violence has been requited with violence (2:13); Nineveh’s hidden arts are destroyed by exposure; as she enslaved “nations,” so she will be bared to the “nations” (cf. Jer 13:26–27; Eze 16:37–41; Hos 2:3–5).

d. The verdict announced (3:7)

7 This section concludes on a note of mourning in response to the Lord’s verdict—mourning occasioned by the presence of death. In v.1 death is foreshadowed in the city’s sin; here it is an accomplished fact, and the witnesses respond in revulsion and amazement to the humiliated prostitute. The “ruins” of Nineveh reflect the Lord’s determination to make a full “end” of it (1:8–29), and the fulfillment of this purpose is amply attested both inscriptionally and archaeologically. The debacle is still regarded as one of the greatest riddles of world history. Within eighty years, Nineveh, which had been raised to unrivaled prominence by Sennacherib and his successors, was obliterated from living memory. The Lord had purposed Nineveh’s end, and the imperial city was never rebuilt. For the next three hundred years at least, there is no evidence that the site of Nineveh was even occupied.

3. Third description of Nineveh’s destruction (3:8–11)

8 In Hebrew “Thebes” is “No Amon” (“the city of Amon”; cf. Jer 46:25; Eze 30:14–16). “Amon” was the chief god of the Theban pantheon and one of the principal deities of Egypt since the New Kingdom (c. 1580–1090 B.C.): the term “No” is derived from the Egyptian word for “city.” Thebes, which lay on the Nile about four hundred miles south of modern Cairo, constituted the chief city of Upper, or southern, Egypt and was a leading center of Egyptian civilization. A place of temples, obelisks, sphinxes, and palaces, it was dominated by the mighty temples of Amon at Luxor and Karnak on the east bank of the Nile, opposite the funerary temples of the kings to the west. Its temples and palaces are said to have found no equal in antiquity, and they are still regarded by some as the mightiest ruins of ancient civilization to be found anywhere in the world.

As intimated above, the city lay on both banks of the Nile. The river was divided into the principal channels by the islands that interrupted its flow. Thebes could truly be described, therefore, as a city “with water around her.” The term “river” (GK 3542) is normally translated “sea”; it is applied elsewhere to the Nile (Isa 18:2; 19:5; cf. Jer 51:36), and indeed the Nile is known as “the sea” to this day. The strategic location of Thebes made the river its natural or “outer” wall of “defense.” In addition, it enjoyed the protection of a main, inner “wall,” visualized again here as constituted by the surrounding waters or extending from them. It is thus equated with Nineveh, similarly defended by a “wall” and by water through its location on a great river (2:5–6, 8).

9 Thebes had intermittent periods of great glory as the capital of Egypt from Middle Kingdom times (c. 2160–1580) onward. After some indifferent periods, the establishment of an Ethiopian dynasty (“Cush”) in the seventh century assured a continuing place for Thebes, with access to the strength of both Egypt and Ethiopia. The adjective “boundless” corresponds to “endless” (2:9), evoking the vast resources shared by the two cities and foreshadowing the “bodies without number” (v.3) that they were destined to share also.

“Libya” lay to the west of Egypt, with which it possessed similar ties: the long-lived Twenty-Second Dynasty had originated from Libya (c. 950–730), exemplified in the ruler Sheshonk I (Shishak; cf. 1Ki 14:25–26). “Put” is also to be located in North Africa on the basis of biblical references that associate it with Egypt and Ethiopia (cf. Ge 10:6; 1Ch 1:8; Jer 46:9; et al.). It is now commonly identified with the same area as Libya. Like Nineveh, Thebes was surrounded not only by natural defenses but by the confederate resources of a vast and ancient empire.

10–11 For all her strength, Thebes fell to the Assyrians (c. 664). The Ethiopian kings had provoked this attack by their policy of intrigue in Palestine. Rather than confront Assyria directly, they tended to incite the minor states to rebel against their Assyrian overlords, with a view to reestablishing Palestine as an Egyptian sphere of influence (cf. Isa 30:1–7; 31:13; 36:6; 37:9). As a result of such intrigue by Tirhakah (689–664; cf. Isa 37:9) with the prince of Tyre, Egypt was invaded by Esarhaddon in 675/674; the campaign was launched in earnest in 671, when the Egyptians were routed before the Assyrians who captured Memphis. Upper Egypt, including Thebes, surrendered; Tirhakah fled south to Ethiopia, and his rule was abrogated in Lower Egypt, which Esarhaddon fragmented under the rule of minor princes.

Esarhaddon died in 669 as he was marching to suppress further insurrection in Egypt, and Tirhakah immediately moved north into Egypt again: Thebes resumed its traditional allegiance to him, Memphis was seized, and Lower Egypt was again overrun. In 667 Ashurbanipal was in a position to take Egypt in hand, reversing the previous sequence of events. Memphis fell to his troops; Thebes surrendered with the rest of Egypt; Tirhakah fled south to Napata where he died. He was succeeded as king of Ethiopia by Tanutamon, who renewed the attempt to control Egypt. Again, Thebes reversed its allegiance, receiving him with acclaim. Memphis was taken, its Assyrian representatives were slaughtered, and Tanutamon gained temporary sovereignty over Egypt. The Egyptians were no match for the Assyrian army, however, which soon returned under Ashurbanipal in 664/663. Tanutamon fled south like his predecessors, the Delta was reconquered, and Thebes fell. Both Ashurbanipal and Esarhaddon had exercised restraint in their Egyptian foreign policy, as a means of securing loyalty in a distant country they could only with difficulty garrison effectively. Now, however, Ashurbanipal’s patience was exhausted. Thebes was razed to the ground, in vengeance on its vacillating allegiance to Ethiopia (cf. 2Ki 17:3–6). His enraged and vehement attack on the city is documented in his annals. From that time on, Thebes has been largely a place of monuments to a glory and dominance now long departed. Both the Egyptian and the Assyrian sources, therefore, validate Nahum’s description of a city scattered to the winds, its posterity cut off, its trained “nobles” plundered, and its leaders fleeing for refuge.

Verse 10 echoes the preceding announcement of judgment on Nineveh in the threat of “exile” (cf. 2:7) and of destruction in the streets (2:4); the human resources represented by its “nobles” suffered the same fate as Nineveh’s “wealth” (2:9; cf. 3:3). And in v.11 this correlation is made explicit. Nineveh has been equated with Thebes in its defenses (v.8); it would surely be equated with Thebes in its downfall. The finality of this sentence is sealed by its further correspondence to 1:2–15. Nineveh would be “drunk” as decreed by the Lord (1:10). She would seek “refuge” (GK 5057) in vain, for she trusted in carved images and idols.

4. Fourth description of Nineveh’s destruction (3:12–19)

a. Onslaught and failing defenses (3:12–14)

12–13 For Nineveh no refuge would be forthcoming. Her “fortresses” (probably walled cities) guarding the approach to Nineveh were ripe for destruction, being dislodged with as little effort as “figs” ready for harvesting. As the “gates” guarding entrance to the land, they were “open” to the enemy like those of Nineveh herself (cf. 2:6). This collapse is explained by the effeminate, weakened condition of her “troops.”

14 The impending condition of “siege” demanded an independent supply of “water,” since the enemy would cut off all external sources provided by the rivers flowing into the city (cf. 2:6). The Babylonian Chronicle corroborates this anticipation of siege, referring to a campaign that lasted three months. It also intimates that operations against the city had begun in 614 under Cyaxares (cf. 2:1), so that Nineveh was subject to intermittent siege for more than two years.

The word for “defenses” (GK 4448) can also mean “fortifications” or walls of the city. “Clay” was the principal building material of Mesopotamia, which lacked adequate resources in stone (cf. Ge 11:3). The walls of Nineveh, which were built of such “worked clay” bricks, averaged fifty feet in breadth, extending to over one hundred feet at the gates; they therefore demanded an enormous effort for their maintenance, as indicated here by the urgent and repeated references to the processes involved.

b. Interpretive analogy and judgment from the Lord (3:15–17)

15 Nineveh’s conquest by fire, together with sword, is amply revealed in its ruins. The devouring fire evokes the destruction inflicted by “grasshoppers” or “locusts” (GK 746), which similarly “consume” all that lies in their path. Verses 15–17 develop this image of “locusts” (cf. Jer 51: 14, 27; Joel 1:4; 2:25) with intricate detail. The initial emphasis is on their omnivorous behavior, typical of locusts. The word “locusts” is related to the Hebrew word meaning “to increase, be many.” The ability of the locust to proliferate in vast numbers underlies its menace to vegetation.

16 Like locusts, Nineveh’s merchants proliferated beyond measure; and they likewise “strip” the land. The comparison to locusts introduces a further element: like locusts, these “merchants” also “fly away,” unconcerned for the region they have exploited.

17 Nineveh’s “officials,” like her “merchants,” are multitudinous as “swarms of locusts”; they “settle” within her boundaries for shelter and food, but they abandon her and “fly away” when tribulation comes. With remarkable artistry Nahum transforms the perspective of the prophecy. Judgment is executed from within by those claiming to serve Nineveh’s interests as they flock to her (v.15); and her fall is explained in terms of the disloyalty of her own people. The Assyrians had based their empire on expediency and self-interest, multiplying power, wealth, and personnel like locusts for their own gratification. Now their empire was to succumb as a victim of the self-interest it had promoted—eaten away from within no less than it was devoured by the sword from without.

c. The verdict announced (3:18–19)

18–19 The collapse of effective loyalty penetrated even Assyria’s aristocracy, represented by its “nobles” and “shepherds,” or “rulers.” Their “slumber” and “rest” foreshadow both their death and the inertia that occasions it. The corollary of this failure is the scattering of the people, “with no one to gather them,” like sheep without “shepherds.” One of the striking phenomena of history is the disappearance of a nation that had existed for two thousand years!

The “king of Assyria” is addressed directly throughout vv.16–19; ultimately it was his fatal injury that accounted for his breakdown in authoritative government and military leadership. As anticipated by Nahum, the dynasty fell with the city. The “wound” could not be healed; the brief attempt by Ashur-uballit to keep the dynasty alive in Haran failed two years later. The injury was indeed fatal.

The book closes with the response of witnesses who heard of these events; the “endless cruelty” was ended!

For his anger lasts only a moment,

but his favor lasts a lifetime;

weeping may remain for a night,

but rejoicing comes in the morning. (Ps 30:5)