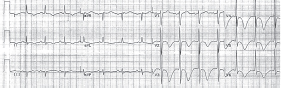

• Rate (? tachy or brady)

• Rhythm (? P waves, ? relationship between P and QRS, ? regular)

• Intervals (PR, QRS, QT) and axis (? LAD or RAD)

• Chamber abnormality (? LAA and/or RAA, ? LVH and/or RVH)

• QRST changes (? Q waves, poor R-wave progression V1–V6, ST ↑/↓ or T-wave Δs)

Figure 1-1 QRS axis

• Definition: axis beyond –30° (S > R in lead II)

• Etiologies: LVH, LBBB, inferior MI, WPW

• Left anterior fascicular block (LAFB): LAD (–45 to –90°) and qR in aVL and QRS <120 msec and no other cause of LAD (eg, IMI)

• Definition: axis beyond +90° (S > R in lead I)

• Etiologies: RVH, PE, COPD (usually not > +110°), septal defects, lateral MI, WPW

• Left posterior fascicular block (LPFB): RAD (90–180°) and rS in I & aVL and qR in III & aVF and QRS <120 msec and no other cause of RAD

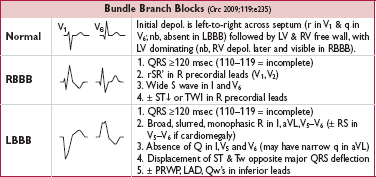

Bifascicular block: RBBB + LAFB/LPFB. Trifascicular block: bifascicular block + 1° AVB (nb, misnomer as 1° AVB involves AV node but no fascicle per se).

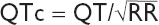

• QT measured from beginning of QRS complex to end of T wave (measure longest QT)

• QT varies w/ HR → corrected w/ Bazett formula:  (RR in sec, can be estimated by 60/HR), overcorrects at high HR and undercorrects at low HR (nl QTc <440 msec

(RR in sec, can be estimated by 60/HR), overcorrects at high HR and undercorrects at low HR (nl QTc <440 msec  and <460 msec

and <460 msec  )

)

• Fridericia’s formula preferred at very high or low

• QT prolongation a/w ↑ risk TdP (espec >500 msec); perform baseline/serial ECGs if using QT prolonging meds, no estab guidelines for stopping Rx if QT prolongs

• Etiologies:

Antiarrhythmics: class Ia (procainamide, disopyramide), class III (amio, sotalol, dofet)

Psych drugs: antipsychotics (phenothiazines, haloperidol, atypicals), Li, ? SSRI, TCA

Antimicrobials: macrolides, quinolones, azoles, pentamidine, atovaquone, atazanavir

Other: antiemetics (droperidol, 5-HT3 antagonists), alfuzosin, methadone, ranolazine

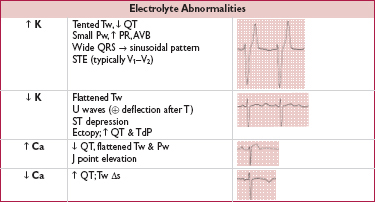

Electrolyte disturbances: hypoCa (nb, hyperCa a/w ↓ QT), ± hypoK, ? hypoMg

Autonomic dysfxn: ICH (deep TWI), stroke, carotid endarterectomy, neck dissection

Congenital (long QT syndrome): K, Na, & Ca channelopathies (Circ 2013;127:126)

Misc: CAD, CMP, bradycardia, high-grade AVB, hypothyroidism, hypothermia, BBB

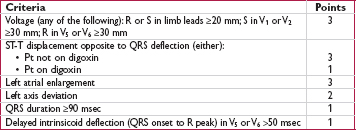

• Etiologies: HTN, AS/AI, HCMP, coarctation of aorta

• Criteria (all w/ Se <50%, Sp >85%; accuracy affected by age, sex, race, BMI)

Romhilt-Estes point-score system (4 points = probable; 5 points = diagnostic):

Sokolow-Lyon: S in V1 + R in V5 or V6 ≥35 mm or R in aVL ≥11 mm

Cornell: R in aVL + S in V3 >28 mm in men or >20 mm in women

If LAD/LAFB, S in III + max (R+S) in precordium ≥30 mm

• Etiologies: cor pulmonale, congenital (tetralogy, TGA, PS, ASD, VSD), MS, TR

• Criteria (all tend to be insensitive, but highly specific, except in COPD)

R > S in V1 or R in V1 ≥7 mm, S in V5 or V6 ≥7 mm, drop in R/S ratio across precordium

RAD ≥+110° (LVH + RAD or prominent S in V5 or V6 → biventricular hypertrophy)

• Ventricular enlargement: RVH (RAD, RAA, deep S waves in I, V5, V6); HCMP

• Myocardial injury: posterior MI (anterior Rw = posterior Qw; often with IMI)

• Abnormal depolarization: RBBB (QRS >120 msec, rSR′); WPW (↓ PR, δ wave, ↑ QRS)

• Other: dextroversion; Duchenne muscular dystrophy; lead misplacement; nl variant

• Definition: loss of anterior forces w/o frank Q waves (V1–V3); R wave in V3 ≤3 mm

• Possible etiologies (nonspecific):

old anteroseptal MI (usually w/ R wave V3 ≤1.5 mm, ± persistent ST ↑ or TWI V2 & V3) cardiomyopathy

LVH (delayed RWP with prominent left precordial voltage), RVH, COPD (which may also have RAA, RAD, limb lead QRS amplitude ≤5, SISIISIII w/ R/S ratio <1 in those leads)

LBBB; WPW; clockwise rotation of the heart; lead misplacement; PTX

• Definition: ≥30 msec (≥20 msec V2–V3) or >25% height of R wave in that QRS complex

• Small (septal) q waves in I, aVL, V5 & V6 are nl, as can be isolated Qw in III, aVR, V1

• “Pseudoinfarct” pattern may be seen in LBBB, infiltrative dis., HCM, COPD, PTX, WPW

• In WPW, Qw pattern may help localize site of accessory pathway (Bundle of Kent)

• Acute MI (upward convexity ± TWI) or prior MI with persistent STE

• Coronary spasm (Prinzmetal’s angina; transient STE in a coronary distribution)

• Pericarditis (diffuse, upward concavity STE; a/w PR ↓; Tw usually upright)

• HCM, Takotsubo CMP, ventricular aneurysm, cardiac contusion

• Pulmonary embolism (occ. STE V1–V3; classically a/w TWI V1–V4, RAD, RBBB, S1Q3T3)

• Repolarization abnormalities

LBBB (↑ QRS duration, STE discordant from QRS complex)

dx of MI in setting of LBBB: Sgarbossa criteria (NEJM 1996;334:481)

≥1 mm STE concordant w/ QRS (Se 73%, Sp 92%)

STD ≥1 mm V1–V3 (Se 25%, Sp 96%)

STE ≥5 mm discordant w/ QRS (Se 31%, Sp 92%)

LVH (↑ QRS amplitude)

Brugada syndrome (rSR′, downsloping STE V1–V2; Na channelopathy a/w SCD)

Hyperkalemia (see below)

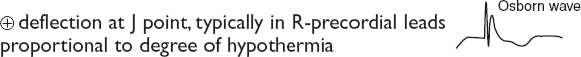

Hypothermia: Osborn waves

• aVR: STE >1 mm a/w ↑ mortality in STEMI; STE aVR > V1 a/w left main disease

• Early repolarization: most often seen in V2–V5 in young adults (JACC 2015;66:470)

1–4 mm elev of peak of notch or start of slurred downstroke of R wave (ie, J point); ± up concavity of ST & large Tw (∴ ratio of STE/T wave <25%; may disappear w/ exercise)

? early repol in inf leads may be a/w ↑ risk of VF (NEJM 2009;361:2529; Circ 2011;124:2208)

• Myocardial ischemia (± Tw abnl) or acute true posterior MI (V1–V3)

• Digitalis effect (downsloping ST ± Tw abnl, does not correlate w/ dig levels)

• Hypokalemia (± U wave)

• Repolarization abnl in a/w LBBB or LVH (usually in leads V5, V6, I, aVL)

• Ischemia or infarct; Wellens’ sign (deep, symmetric precordial TWI) → proximal LCA lesion

(Wellens’ sign, from Cuculich PS and Kates AM. The Washington Manual Cardiology Subspecialty Consult, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2014:286.)

• Myopericarditis; CMP (Takotsubo, ARVC, apical HCM); MVP; PE (espec if TWI V1–V4)

• Repolarization abnl in a/w LVH/RVH (“strain pattern”), BBB

• Posttachycardia or postpacing

• Electrolyte, digoxin, PaO2, PaCO2, pH or core temperature disturbances

• Intracranial bleed (“cerebral T waves,” usually w/ ↑ QT)

• Normal variant in children (V1–V4) and leads in which QRS complex predominantly

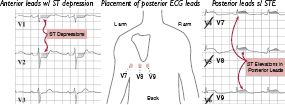

• STD ± ↑ R wave in leads V1–V4 may correspond to acute posterior “ST-elevation” MI

• ✓ Posterior ECG leads; manage as a STEMI with rapid reperfusion

(Modified from Martindale JL, Brown DFM. Rapid Interpretation of ECGs in Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012:364,376)

• QRS amplitude (R + S) <5 mm in all limb leads & <10 mm in all precordial leads

• Etiologies: COPD (precordial leads only), pericardial effusion, myxedema, obesity, pleural effusion, restrictive or infiltrative CMP, diffuse CAD

(ECGs modified from Wagner GS, Strauss DG. Marriott’s Practical Electrocardiography, 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014)

(Braunwald’s Heart Disease, 10th ed, 2014)

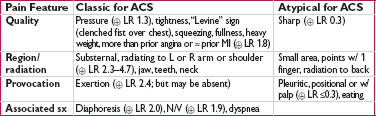

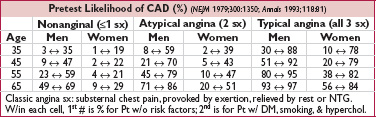

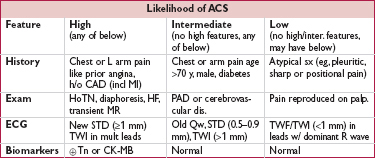

• Focused history: quality & severity of pain; location & radiation; provoking & palliating factors; intensity at onset; duration, frequency & pattern; setting in which it occurred; associated sx; cardiac hx and risk factors

(JAMA 2005;294:2623)

• Targeted exam: VS (including BP in both arms), cardiac gallops, murmurs or rubs; signs of vascular disease (carotid or femoral bruits, ↓ pulses), signs of heart failure; lung & abdominal exam; chest wall exam for reproducibility of pain

• 12-lead ECG: obtain w/in 10 min; c/w priors & obtain serial ECGs. In addition, consider:

posterior leads (V7–V9; remove V4–V6 and place in post axillary, mid-clavic & L paraspinal position) useful to ✓ for posterior STEMI if hx c/w ACS but stnd ECG unrevealing, espec if ST ↓ V1–V4 (ant ischemia vs post STEMI) or R/S V1–V2 >1

R-sided leads (place V3–V6 in mirror image position on R side of chest) in inferior STEMI to detect RV involvement

• CXR; other imaging (echo, PE CTA, etc.) as indicated based on H&P and initial testing

• Biomarkers (see below): Tn preferred biomarker, ✓ at baseline & 3–6 h after sx onset

• Troponin: level >99th %ile w/ rise & fall in approp. setting is dx of MI; >95% Se, 90% Sp Detectable 1–6 h after injury, peaks 24 h, may remain elevated for 7–14 d in STEMI Tn may be ↑ in CKD in absence of ACS, ∴ add CK-MB/serial Tn for confirmation

Sensitive Tn assays: 98% Se, 90% Sp, 75% PPV, 99% NPV w/in 3 h of admit to ED, 82% Se & 95% NPV at time of admission to ED (JAMA 2011;306:2684)

High-sensitivity Tn assays quantify Tn in majority of healthy individ.; prog value in asx general pop., stable CAD & DM (NEJM 2009;361:2538 & 2015;373:610; JAMA 2010;304:2503)

• CK-MB: less Se & Sp than Tn for dx of MI

Sources include skeletal muscle, tongue, diaphragm, intestine, uterus, prostate

CK-MB relative index (ratio of CK-MB to CK) >2.5–3 suggests cardiac vs skel. muscle

CK-MB begins to rise 4–6 h post MI (may take 12 h) and returns to baseline w/in 36–48 h

May aid in gauging timing of MI ( Tn &

Tn &  CK-MB suggests MI several days ago)

CK-MB suggests MI several days ago)

May help dx reinfarction if Tn already elevated; however, Tn should ↑ as well

• Myoglobin & heart-type fatty acid binding protein are smaller molecules that may appear in circulation as early as 30 min after MI, but lack of specificity limits utility

• D-dimer: low level useful to r/o PE (qv) and aortic dissection (qv)

• B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP): elevations not specific for ACS but suggest ↑ ventricular wall stress seen not only in decompensated HF, but also ACS & PE

Interpretation of elevated cardiac biomarkers (troponin or CK-MB)

• Does it reflect true myocardial injury? Almost always the case for Tn; CK-MB less specific.

• If myocardial injury, what is the pathobiology? Ddx includes:

MI (injury due to ischemia): rise and/or fall in cardiac biomarker (preferably Tn) >99th %ile w/ ≥1 of the following:

1) sx of ischemia

2) new Qw

3) new ST∆ or LBBB

4) intracoronary thrombus

5) imaging evidence of new loss of myocardium or regional wall motion abnl

non-ischemic injury (eg, myocarditis/toxic CMP, cardiac contusion)

multifactorial (eg, PE, sepsis, severe HF, renal failure, Takotsubo, infiltrative disease)

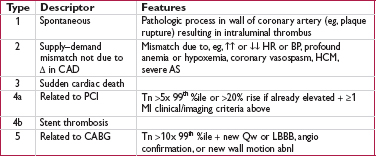

• If MI, what type? (Circ 2012;126:2020)

• Classification important as antithrombotic Rx relevant for type 1 but not type 2 MI, whereas anti-ischemic Rx (↑ O2 supply & ↓ demand) particularly important for type 2

Early noninvasive imaging (also see noninvasive evaluation of CAD)

• If low prob of ACS (eg,  ECG & Tn) & stable → noninvasive fxnal or imaging test

ECG & Tn) & stable → noninvasive fxnal or imaging test

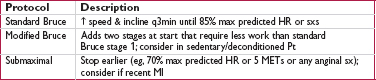

• Treadmill electrocardiography: can be performed after 6–8 h of evaluation

• Radionuclide imaging in Pts who cannot exercise or have uninterpretable ECG

• Can perform acute rest perfusion imaging if ongoing or recent (w/in 2 h) pain ( scan r/o ischemia;

scan r/o ischemia;  scan could represent ischemia or infarct, need pain-free rest images)

scan could represent ischemia or infarct, need pain-free rest images)

• Echo (w/ or w/o stress) to assess for regional wall motion abnl; interpretation difficult in those w/ h/o prior MI

• Coronary CT angio (CCTA): NPV 98% for signif CAD, but PPV 35% for ACS; helpful to r/o CAD if low-intermed prob of ACS. CCTA vs noninvasive fxnal test for ischemia → ↓ time to dx & LOS, but ↑ probability of cath/PCI, contrast exposure & ↑ radiation (NEJM 2012;366:1393 & 367:299; JACC 2013;61:880)

• “Triple r/o” CT angiogram for CAD, PE, AoD

• Indications: dx CAD, evaluate Δ in clinical status in Pt w/ known CAD, risk stratify s/p ACS, evaluate exercise tolerance, localize ischemia (imaging required)

• Contraindications (Circ 2002;106:1883; & 2012;126:2465)

Absolute: AMI w/in 48 h, high-risk UA, acute PE, severe sx AS, uncontrolled HF, uncontrolled arrhythmias, myopericarditis, acute aortic dissection

Relative: left main CAD, mod valvular stenosis, severe HTN, HCMP, high-degree AVB, severe electrolyte abnl

• Generally preferred if patient can exercise to a meaningful level; Se ∼65%, Sp ∼80%

• Typically via treadmill

• Stationary cycle or arm ergometry (lower max workload) if Pt cannot walk

• Hold anti-ischemic meds (eg, nitrates, βB, CCB, ranolazine) if trying to dx obstructive CAD, but continue meds when assessing if Pt ischemic on current med regimen

• Use if unable to exercise, low exerercise tolerance, or recent MI. Se & Sp ≈ exercise.

• Preferred if LBBB or V-paced, as higher prob of false  exercise imaging (typically reversible or fixed anteroseptal defect).

exercise imaging (typically reversible or fixed anteroseptal defect).

• Coronary vasodilator: diffuse coronary arteriolar vasodilation → relative “coronary steal” from vessels w/ fixed epicardial disease. Reveals CAD, but not if Pt ischemic w/ exercise. Options include:

Adenosine or dipyridamole (↓ adenosine reuptake). Side effects: flushing, bradycardia & AVB, dyspnea & bronchospasm.

Selective A2A receptor agonist (eg, regadenoson): less flushing, dyspnea, bronchospasm

Longer half-life of dipyridamole & regadenoson allow to be combined w/ exercise

Avoid caffeine (adenosine receptor antagonist) w/in 12 h of test. Conversely, can use aminophylline to reverse effects of these agents.

Contraindic: HoTN, sick sinus, high-degree AVB, bronchospasm (selective agents safer)

• Chronotropes/inotropes (more physiologic): dobutamine (may precip tachyarrhythmia)

• Use if uninterpretable ECG (V-paced, LBBB, resting ST ↓ >1 mm, digoxin, LVH, WPW), after indeterminate ECG test, or if pharmacologic test

• Use when need to localize ischemia (often used if prior coronary revasc)

• Ideally use exercise as stress modality rather than pharmacologic

• Radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging w/ images obtained at rest & w/ stress

SPECT (eg, 99mTc-sestamibi): Se ∼85%, Sp ∼80%

PET (rubidium-82): Se ∼90%, Sp ∼85%

ECG-gated imaging allows assessment of LV fxn (including regional systolic wall thickening or lack thereof as a sign of ischemia/infarction)

• Echo (exercise or dobuta): Se ∼85%, Sp ∼85%; no radiation; operator dependent

• Cardiac MRI (w/ pharmacologic stress) another option with excellent Se & Sp

• HR (must achieve ≥85% of max pred HR [220 – age] for exer. test to be dx), BP response, peak double product (HR × BP; nl >20k), HR recovery (HR*peak – HR1 min later; nl >12)

• Max exercise capacity achieved (METS or min)

• Occurrence of symptoms (at what level of exertion and similarity to presenting sx)

• ECG Δs: downsloping or horizontal ST ↓ (≥1 mm) 80 ms after QRS predictive of CAD upsloping ST ↓ w/ rapid return to baseline usually due to ↑ HR & atrial repol artifact lead V5 most sensitive; Δs isolated to inferior leads may be artifact location of ST ↓ does not localize ischemic territory

STE: highly predictive of CAD & localizes; in aVR suggests LM CAD; nonspecific if in leads w/ prior Qw

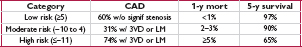

• Duke treadmill score = exercise min – (5 × max ST dev) – (4 × angina index) [angina index = 0 none, 1 nonlimiting sxs, 2 limiting sxs]

• Imaging: radionuclide defects or echocardiographic regional wall motion abnormalities reversible defect = ischemia; fixed defect = infarct; transient isch dilation = severe CAD false  : breast → ant “defect” and diaphragm → inf “defect” false

: breast → ant “defect” and diaphragm → inf “defect” false  may be seen if balanced (eg, 3VD) ischemia (global ↓ perfusion w/o regional Δs)

may be seen if balanced (eg, 3VD) ischemia (global ↓ perfusion w/o regional Δs)

• ECG: ST ↓ ≥2 mm or ≥1 mm in stage 1 or in ≥5 leads or ≥5 min in recovery; STE; VT

• Physiologic: ↓ or fail to ↑ BP, <4 METS, angina during exercise, Duke score ≤ –11; ↓ EF

• Radionuclide: ≥1 lg or ≥2 mod. reversible defects, transient LV cavity dilation, ↑ lung uptake

• High-risk test has PPV ∼50% for LM or 3VD, ∴ consider coronary angio

• Viable myocardium = dysfxn at rest, but not scarred and has potential for recovery

• Goal: identify hibernating or stunned myocardium that could regain fxn after revasc

• However, in Pts w/ ↓ EF, presence of viability did not identify differential clinical benefit from CABG vs med Rx (NEJM 2011;364:1617)

• High NPV to r/o CAD, but low PPV

• In Pts presenting with CP, presence of plaque sensitive (100%) but not specific (54%) for ACS, ∴ NPV 100%, PPV 17% (JACC 2009;53:1642). CCTA vs noninvasive fxnal test for ischemia → ↓ time to dx & LOS, but ↑ probability of cath/PCI, contrast exposure & ↑ radiation (NEJM 2012;366:1393 & 367:299; JACC 2013;61:880).

• In sx outPt, CCTA vs fxnal testing led to more radiation, coronary angiography & revascularization, but no difference in clinical outcomes (PROMISE NEJM 2015;372:1291)

• CCTA images may be limited if: HR >60–70 bpm, irregular rhythm, calcium deposition or stents (may create artifact), inability to breath hold 5 sec, vessel diameter <1.5 mm. Image quality best at slower & regular HR (? give βB if possible, goal HR 55–60).

• Useful for assessing patency of bypass grafts

• Unlike CCTA, does not require iodinated contrast, HR control or radiation exposure. Can also assess LV fxn, enhancement (early = microvasc obstruction; late = MI). Limitations: cost, operator-dependent, long duration, ↓ spatial resolution.

• In head-to-head comparisons, CMRI and CCTA appear to have grossly comparable sensitivity and specificity (JACC 2005;46:92; Annals 2006;145:207)

• Quantifies extent of calcium; thus estimates plaque burden (but not % coronary stenosis)

• Compared w/ CCTA, CAC score assessment requires lower radiation exposure (1–2 mSv)

• CAC sensitive (91%) but not specific (49%) for presence of CAD; high NPV to r/o CAD

• ? value as screening test to r/o CAD in sx Pt (CACS <100 → 3% probability of signif CAD; but interpretation affected by age, gender)

• May provide incremental value to clinical scores for risk stratification (JAMA 2004;291:210). ACC/AHA guidelines note CAC assessment is reasonable in asx Pts w/ intermed risk (10–20% 10-y Framingham risk; ? value if 6–10% 10-y risk) (Circ 2010;122:e584).

• Prevalence: 20–39 y: <1%; 40–59 y: 5-6%; 60–79 y: 21% in  & 11% in

& 11% in  ; ≥80 y: 35% in

; ≥80 y: 35% in  & 19% in

& 19% in  ; lifetime risk after age 40: 50% in men & 32% in women

; lifetime risk after age 40: 50% in men & 32% in women

• Ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains leading cause of death in both men & women

• Initiate workup if suspected new dx of IHD or Δ in clinical status

• H&P, ECG (looking for ischemic or prior infarct Δs such as Qw, PRWP, ST or Tw abnl)

• Noninvasive testing (qv) if intermediate risk (ie, >10–20% & <80–90%). If Pt has low prob, then ↑ risk false  ; if very high prob,

; if very high prob,  test does not adeq r/o CAD, ∴ consider cor angio.

test does not adeq r/o CAD, ∴ consider cor angio.

• Coronary angio if: high-risk noninv results (qv); very high pretest prob; refract angina;

uncertain dx after noninvasive testing (& compelling need to determine dx), occupational need for definitive dx (eg, pilot) or inability to undergo noninvasive testing;

survivor of SCD or life-threatening vent. arrhythmia; unexplained heart failure or ↓ EF;

suspected spasm or nonatherosclerotic cause of ischemia (eg, anomalous coronary)

• ASA 75–162 mg/d; βB for 3 y post MI or if ↓ EF; statin (typically high intensity; see “Lipids”)

• ACEI (or ARB) if HTN, DM, CKD or ↓ EF

• Risk factor targets: BP <140/90 (consider <130/80 if prior MI), HbA1c 7–9% (<7% if long life expect.), BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2

• Smoking cessation; influenza vaccine

• Diet: ↑ veg, fruits, whole grains; ↓ sweets, sugar-sweetened bevs & red meat; sat fat 5–6% total cals, trans fat <1% total cals, chol <200 mg/d; Na ≤2400 mg/d (ideally ≤1500 mg/d)

• Exercise: ∼40 min moderate-to-vigorous physical activity 3–4x/wk

• Beta blockers 1st-line therapy

• CCB (verap/dilt or long-acting dihydro) or long-acting nitrates: add-on or if βB intolerant

• Ranolazine (↓ late inward Na+ current to ↓ myocardial demand): add-on or if βB intolerant

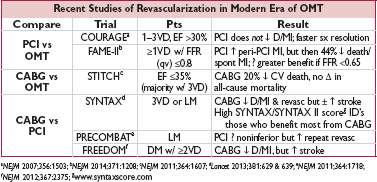

• If unacceptable angina despite max tolerated med Rx or if potential to improve survival

• OMT should be initial focus if stable & w/o critical anatomy & w/ normal EF

• Older studies showed survival benefit w/ revasc (CABG) vs med Rx (pre-statin era) if: LM (≥50% stenosis), 3VD (≥70% stenoses) espec if ↓ EF, 2VD w/ critical prox LAD, ? 1–2 VD w/ large area of viable, ischemic myocardium

• LM or 3VD: CABG, espec if ↓ EF or DM; consider PCI if SYNTAX score ≤22 & high surg risk

• 2VD w/ prox LAD, ↓ EF, or extensive ischemia: CABG (espec if DM) or ? PCI

• ? 1VD (low FFR) w/ prox LAD + either ↓ EF or extensive ischemia: PCI or CABG (w/ LIMA)

• Exp’t device to narrow coronary sinus ↓ angina (NEJM 2015;372:517)

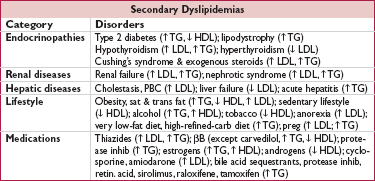

• Lipoproteins = lipids (cholesteryl esters & triglycerides) + phospholipids + proteins include: chylomicrons, VLDL, IDL, LDL, HDL, Lp(a)

• Measure after 12-h fast; LDL is typically calculated w/ Friedewald equation:

LDL-C = TC – HDL-C – (TG/5) [last term assumes TG:VLDL ratio = 5:1]; underestim. if TG >400 or LDL-C <70 mg/dL (JAMA 2013;310:2061); ∴ directly measure LDL-C

Non–HDL-C (TC – HDL-C) and apoB are alternative nonfasting measures of risk

Lipid levels stable up to 24 h after ACS and other acute illnesses, then ↓ and may take 6 wk to return to nl

• Metabolic syndrome (≥3 of following): waist ≥40” ( ) or ≥35” (

) or ≥35” ( ); TG ≤150; HDL <40 mg/dL (

); TG ≤150; HDL <40 mg/dL ( ) or <50 mg/dL (

) or <50 mg/dL ( ); BP ≤130/85 mmHg; fasting glc ≤100 mg/dL (Circ 2009;120:1640)

); BP ≤130/85 mmHg; fasting glc ≤100 mg/dL (Circ 2009;120:1640)

• Lp(a) = LDL particle bound to apo(a) via apoB; genetic variants a/w MI (NEJM 2009;361:2518)

• Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH, 1:500): defective LDL receptor; ↑↑ chol, nl TG; ↑ CAD

• Familial defective apoB100 (1:1000): similar to FH

• Familial combined hyperlipidemia (1:200): polygenic; ↑ chol, ↑ TG, ↓ HDL; ↑ CAD

• Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia (1:10,000): ↑ chol & TG; xanthomas; ↑ CAD

• Familial hypertriglyceridemia (FHTG, 1:500): ↑ TG, ± ↑ chol, ↓ HDL, pancreatitis

• Tendon xanthomas: seen on Achilles, elbows and hands; implies LDL >300 mg/dL

• Eruptive xanthomas: pimple-like lesions on extensor surfaces; implies TG >1000 mg/dL

• Xanthelasma: yellowish streaks on eyelids seen in various dyslipidemias

• Corneal arcus: common in older adults, imply hyperlipidemia in young Pts

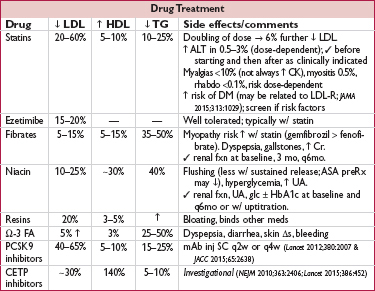

• Statins: every 1 mmol (39 mg/dL) ↓ LDL-C → 22% ↓ major vascular events (CV death, MI, stroke, revasc) in individuals w/ & w/o CAD (Lancet 2010;376:1670); ∴ mainstay of therapy as potent, safe and well-tolerated

• Consistent CV benefit even in individuals starting w/ LDL-C ≤60 mg/dL (JACC 2011;57:1666)

• No clear evidence to date to suggest any harm from achieving very low LDL-C levels

• Elevated hs-CRP may identify Pts who derive ↑ benefit (NEJM 2001;344:1959 & 2008;359:2195)

• Similar clinical benefit also seen w/ some older nonstatin Rxs (resins, fibrates, niacin) when sufficiently lowered LDL-C (JACC 2005;46:1855)

• Ezetimibe: ↓ major vascular events incl MI & stroke when added to statin post-ACS, w/ magnitude of benefit consistent w/ LDL-statin relationship (IMPROVE-IT, NEJM 2015;372:2387)

• PCSK9 inhibitors: ∼60% ↓ LDL on top of statin, as monoRx, and in FH (EHJ 2014;35:2249); prelim data w/ encouraging ↓ CV outcomes (NEJM 2015;372:1500), definitive trials ongoing

• Low levels of HDL-C associated with ↑ risk of MI

• However, Mendelian randomization studies do not support causal role (Lancet 2011;380:572)

• Niacin: in Pts w/ well-controlled LDL-C (<80 mg/dL) on a statin, minimally ↓ LDL, modestly ↑ HDL, and did not ↓ CV events (NEJM 2011;365:2255 & 2014;371:203)

• CETP inhibitors: one that ↑ HDL-C by 25% did not lead to clinical benefit in Pts w/ well-controlled LDL-C on a statin (NEJM 2012;367:2089); CV outcomes trials of inhibitors that ↑ HDL-C by 140% and ↓ LDL-C by ∼30% ongoing (NEJM 2010;363:2406; JAMA 2011;306:2099)

• Reasonable to treat very high levels (>500–1000 mg/dL) to ↓ risk of pancreatitis

• High levels of TG associated with ↑ risk of MI, but whether causal remains debated

• Fibrates (gemfibrozil & fenofibrate): mixed data in terms of ↓ vascular events, ? greater benefit if high TG (Circ 1992;85:37; NEJM 1999;341:410; Lancet 2005;366:1849; NEJM 2010;362:1563)

• Fish oil (containing Ω-3 fatty acids EPA & DHA): recent meta-analyses suggest supplementation w/o meaningful effect on CV events (JAMA 2012;308:1024)

• APOC3 inhibitors under study and ↓ TG by up to ∼70% (NEJM 2015;373:438)

• Consider ↓ to <50 mg/dL w/ niacin in intermed- to high-risk Pts (EHJ 2010;31:2844–53); however, benefit unclear espec if LDL-C well controlled (JACC 2014;63:520)

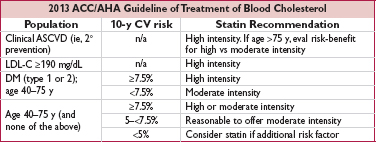

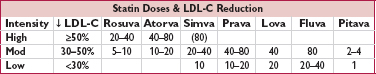

• Focus now on statin strategies, rather than achieving LDL-C goals

• Clinical atherosclerotic CV disease (ASCVD) includes h/o ACS, stable angina, arterial revasc, stroke, TIA, or PAD presumed to be of atherosclerotic origin

• 10-y CV Risk Score for CHD or stroke based on age, sex, race, SBP, TC, LDL, DM, tobacco, BP Rx; http://my.americanheart.org/cvriskcalculator

• Additional risk factors to consider include: LDL-C ≥160 mg/dL, genetic hyperlipid., FHx premature ASCVD, hsCRP >2 mg/L, CAC score ≥300 or ≥75th %ile, ABI <0.9.

• If statin intolerant or LDL-C remains elevated despite high-intensity statin (as well as reinforcement of med adherence, lifestyle changes and exclusion of 2° causes of dyslipidemia) nonstatin LDL-lowering therapies remain reasonable

• If Pt does not tolerate high-intensity statin, consider dose reduction before d/c statin

Doses are in mg. Simva 80 mg has ↑ myopathy risk and should not be used unless dose already tolerated >12 mo.

• Document peripheral arterial exam (radial, femoral, DP, PT pulses; bruits); if plan for radial artery access, ✓ palmar arch intact (eg, w/ pulse oximetry & plethysmography), although value remains unproven (JACC 2014;63:1833)

• Ensure Pt can lie flat for several hours

• ✓ CBC, PT-INR (ideally ≤1.5), & Cr; blood bank sample

• NPO >6 h; IVF if appropriate (± bicarb; acetylcysteine no longer rec; see “CIAKI”)

• Femoral artery commonly used; high puncture ↑ risk of retroperitoneal bleed; low puncture ↑ risk of peripheral arterial complic.; can access a synthetic graft if a few months old

• Radial artery: 33% ↓ major bleeding, trend to 15% ↓ in MACE & 28% ↓ mortality, espec if >80% of cases at center done radially (Lancet 2015;385:2465)

• Aspirin: 325 mg × 1 (≥2 h prior to angio) → 81 mg qd

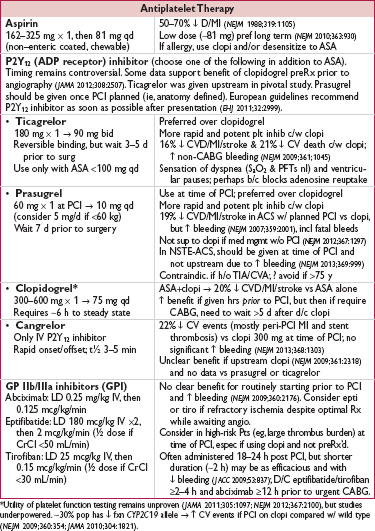

• P2Y12 inhibitor (choose one):

clopidogrel: 600 mg × 1 → 75 mg qd; preRx ↓ MACE (JAMA 2005;294:1224 & 2012;308:2507) prasugrel or ticagrelor (only in ACS, qv)

cangrelor (IV, short-acting): ↓ early ischemic events vs clopi given w/o preload (NEJM 2013;368:1303)

• GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor: consider adding abciximab, eptifibatide, or tirofiban; data showing ↓ MACE largely before routine P2Y12 inhibition and w/ UFH as anticoagulant. Remains reasonable espec if using clopidogrel and did not preRx.

• Anticoagulant (choose one; typically d/c’d at end of PCI):

UFH: most common choice in U.S.

bivalirudin: ↓ bleeding (espec vs UFH + GP IIb/IIIa inhib; JAMA 2015;313:1336), ± ↑ MI, ↑ stent thrombosis in STEMI (not mitigated by longer infusion), ↓ mortality in some but not all trials (Lancet 2014;384:599; MATRIX NEJM 2015); use if Pt has HIT

enoxaparin (nb, cannot ✓ degree of anticoag)

• Statin (high-dose): PreRx ↓ peri-PCI myonecrosis (Circ 2011;123:1622) & ↓ risk of contrast- induced nephropathy (JACC 2014;63:71)

• Balloon angioplasty (POBA): effective, but c/b dissection & elastic recoil & neointimal hyperplasia → restenosis; now reserved for small lesions & ? some SVG lesions

• Bare metal stents (BMS): ↓ elastic recoil → 33–50% ↓ restenosis & repeat revasc (to ∼10% by 1 y) c/w POBA; requires P2Y12 inhibitor ≥4 weeks (ideally up to 6 mo)

• Drug-eluting stents (DES)

antiproliferative drug released over several weeks → ↓ neointimal hyperplasia ∼75% ↓ restenosis, ∼50% ↓ repeat revasc (to <5% by 1 y), no Δ D/MI (NEJM 2013;368:254)

delayed re-endothelialization & potentially proinflammatory polymers may cause ↑ in risk of late stent thrombosis; requires P2Y12 inhibitor ≥6 mo

next generation DES (eg, w/ everolimus) w/ lower risk of stent thrombosis vs BMS (Lancet 2012;379:1393)

• Fractional flow reserve (FFR): ratio of max flow (induced by IV or IC adenosine) distal vs proximal to a stenosis; if used to guide PCI (ie, revasc only if FFR <0.8) → ↓ # stents & ↓ D/MI/revasc (NEJM 2009;360:213)

• Thrombus aspiration: small study showed manual aspiration of thrombus pre-PCI in STEMI ↓ mortality, but larger studies show no benefit and ↑ stroke (Lancet 2008;371:1915; NEJM 2013;369:1587 & 2015;372:1389)

• Postprocedure ✓ vascular access site, distal pulses, ECG, CBC, Cr

• Vascular closure devices speed time to hemostasis and ↓ incidence of hematoma (JAMA 2014;312:1981)

• Bleeding

hematoma/overt bleeding: manual compression, reverse/stop anticoag

retroperitoneal bleed (if puncture above inguinal ligament)

may p/w ↓ Hct ± flank or back pain; ↑ HR & ↓ BP late

Dx w/ abd/pelvic CT (I−)

Rx: reverse/stop anticoag (d/w interventionalist), IV fluids/PRBC/plts as required; if bleeding uncontrolled, consult performing interventionalist or surgery

• Vascular damage (∼1% of dx angio, ∼5% of PCI; Circ 2007;115:2666)

pseudoaneurysm: hematoma w/ continued communication to artery

can present w/ triad of pain, expansile mass, systolic bruit; diagnose w/ U/S;

Rx (if pain or >2 cm): U/S-directed thrombin injection (>95% success, depends on anatomy); surgical repair if very large or if minimally invasive Rx fails

AV fistula: continuous bruit; Dx: U/S; Rx: surgical repair

limb ischemia (emboli, dissection, clot): cool, mottled extremity, ↓ distal pulses; Dx: pulse volume recording (PVR), angio; Rx: percutaneous or surgical repair

• Peri-PCI MI: >5× ULN of Tn/CK-MB + either sx or ECG/angio/imaging Δs; Qw MI in <1%

• Renal failure: contrast-induced manifests w/in 24 h, peaks 3–5 d (see “CIAKI”)

• Cholesterol emboli syndrome

typically seen in middle-aged & elderly and w/ heavy burden of aortic atheroma

multiple clinical manifestations (although may be delay between cath & s/s) including: intact distal pulses but livedo reticularis pattern and toe necrosis (“blue toe syndrome”) renal failure: late and progressive (thus unlike CIAKI), ± eos in urine mesenteric ischemia: abd pain, GIB, pancreatitisCNS: TIA, stroke, amaurosis fugax, Hollenhorst plaques (bright retinal lesion)

Dx: can only be confirmed by biopsy; may see ↑ circulating eos, ↓ complement, ↑ CRP, ↑ ESR, ↑ plts, ↑ fibrinogen

Rx: supportive; no clear benefit for anti-inflam or anticoagulant Rx

• Stent thrombosis (acute clot formation in stent): rare event, but high mortality can occur anytime between mins to yrs after PCI

typically p/w ACS (often STEMI)

typically due to either mechanical problem (stent underexpansion or unrecognized dissection, typically presents early) or d/c of antiplt Rx (espec if d/c both ASA & P2Y12 inhib; JAMA 2005;293:2126)

• In-stent restenosis (neointimal hyperplasia): months after PCI, typically p/w gradual ↑ angina (10% p/w ACS). Due to combination of elastic recoil and neointimal hyperplasia; ↓ w/ DES vs BMS.

• In Pts w/ MI (qv), goal of antiplatelet therapy is ↓ CVD, MI, and stroke as well as rarer event of stent thrombosis. ∴ Long-term therapy beyond 12 mo is logical and has been shown to ↓ CV death, MI, and stroke (NEJM 2015;372:1791; JACC 2007;49:1982 & 2015;65:2211).

• In Pts w/ SIHD, concern for late (>30 d) stent thrombosis led to recs for 12-mo duration, but newer generation stents have lower risk of stent thrombosis

• Several small trials showed shorter duration of P2Y12 inhibition (3–6 vs 12 mo) led to nonstatistically significant higher rates of MI and ST (but still infrequent) but less bleeding (JACC 2012;60:1340; JAMA 2013;310:2510; EHJ 2015;36:1252)

• Much larger DAPT trial showed that longer inhibition (30 vs 12 mo) led to 29% ↓ MACE and 71% ↓ ST (although rates and absolute risk reduction very low with newer generation stents), but ↑ bleeding and, in Pts w/ SIHD, marginally significant ↑ mortality (driven by non-CV mortality) (NEJM 2014;371:2155)

• If possible, postpone major invasive procedures ≥1 mo after BMS or ≥3–6 mo after DES

• If not possible and high of risk bleeding during procedure, d/c prasugrel 7 d, clopidogrel 5 d, or ticagrelor 5 d (per prescribing information, but in major clinical trial, just ∼3 d) prior to procedure. Continue ASA and resume P2Y12 inhibitor w/ loading dose ASAP per surgery.

• If high-risk stent and bridging required, consider short-acting GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (eptifibatide or tirofiban) from 3 d until 4–6 h prior to surgery (Circ 2013;128:2785). Consider cangrelor (IV reversible P2Y12 inhib) (JAMA 2012;307:265).

• “Mini-CABG” = minimally invasive. Thoracotomy or partial sternotomy rather than full sternotomy. Advantages include ↓ pain & ↓ LOS. May be on- or off-pump.

• Off-pump (“beating heart surgery”): avoids cardiopulmonary bypass but makes anastomotic suturing more challenging. In 1 study, ↑ CV death and ↓ graft patency at 12 mo c/w on-pump (NEJM 2009;361:1827); other studies w/ ≈ mortality w/ off- vs on-pump.

• Robotic: type of mini-CABG where endoscopic instruments inserted via small incisions to anastomose the LIMA to the LAD on closed chest and beating heart

• Hybrid procedures: typically involves combo of LIMA-LAD mini-CABG with PCI of other vessels

• Nonatherosclerotic coronary artery disease

Spasm: Prinzmetal’s variant, cocaine-induced (6% of CP + cocaine use r/i for MI)

Dissection: spontaneous (vasculitis, CTD, pregnancy), aortic dissection with retrograde extension (usually involving RCA → IMI) or mechanical (catheter, surgery, trauma)

Embolism (Circ 2015;132:241): AF, thrombus/myxoma, endocard., prosth valve; thrombosis

Vasculitis: Kawasaki syndrome, Takayasu arteritis, PAN, Churg-Strauss, SLE, RA

Congenital: anomalous origin from aorta or PA (coronary compressed), myocardial bridge (intramural segment)

• Ischemic imbalance not due to plaque rupture (“type 2” MI): ↑ myocardial O2 demand (eg, ↑ HR, anemia, AS) or ↓ supply (hypotension, severe anemia)

• Direct myocardial injury: myocarditis; Takotsubo/stress CMP; toxic CMP; cardiac contusion

• Typical angina: retrosternal pressure/pain/tightness ± radiation to neck, jaw or arms precip. by exertion, relieved by rest or NTG; in ACS, new-onset, crescendo or at rest; see “Chest Pain” for likelihood ratios for different sx

• Associated symptoms: dyspnea, diaphoresis, N/V, palpitations or lightheadedness

• Many MIs (∼20% in older series) are initially unrecognized b/c silent or atypical sx

• Atypical sxs (incl N/V & epig pain) may be more common with inferior ischemia

• Women may have ↑ freq of atypical sx vs men

• Signs of ischemia: S4, new MR murmur 2° pap. muscle dysfxn, paradoxical S2, diaphoresis

• Signs of heart failure: ↑ JVP, crackles in lung fields,  S3, HoTN, cool extremities

S3, HoTN, cool extremities

• Signs of other vascular disease: asymmetric BP (aortic dissection or subclavian disease), carotid or femoral bruits, ↓ distal pulses

• ✓ w/in 10 min of presentation, q15–30min × 1 h if initial ECG non-dx, w/ any Δ in sx, and routinely at 6–12 h; compare w/ baseline

• Signs of ischemia (JAMA 1998;280:1256)

STE: generally ≥1 mm in ≥2 contiguous leads (see “STEMI” for details)

new or presumed new (ie, not known to be old) LBBB w/ compelling H&P

STD ≥0.5 mm ( LR 3–5), TWI ≥2 mm (

LR 3–5), TWI ≥2 mm ( LR 2–3), hyperacute Tw

LR 2–3), hyperacute Tw

• Qw or PRWP may suggest prior MI, ∴ higher pretest probability of CAD

• Dx of STEMI if old LBBB (Sgarbossa’s criteria): ≥1 mm STE concordant w/ direction of QRS (Se 73%, Sp 92%), STD ≥1 mm V1–V3 (Se 25%, Sp 96%) or STE ≥5 mm discordant w/ QRS (Se 31%, Sp 92%)

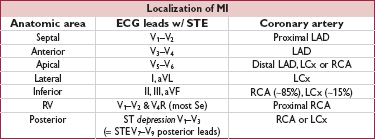

If ECG non-dx and suspicion high, consider addt’l lateral (posterior) leads (V7–V9) to further assess distal LCx/RCA territory. Check right-sided precordial leads in patients with IMI to help detect RV involvement (STE in V4R most Se). STE in III > STE in II and lack of STE in I or aVL suggest RCA rather than LCx culprit in IMI.

• Troponin (Tn) preferred over CK-MB

• ✓ Tn at baseline & 3–6 h after sx onset; may also ✓ beyond 6 h if high index of suspicion based on clinical presentation or ECGs or if sx Δ

• Rise to >99th %ile in approp. clinical setting dx of MI (see “Chest Pain”)

• In Pts w/ ACS & ↓ CrCl, ↑ Tn still portends poor prognosis (NEJM 2002;346:2047)

• If low prob, stress test, CT angio or rest perfusion imaging to r/o CAD (see “Chest Pain”)

• TTE (new wall motion abnl) suggestive of ACS but not specific, as may be seen if old MI

• Coronary angio gold standard for evaluation of CAD

• Coronary spasm → transient STE usually w/o MI (but MI, AVB, VT can occur)

• Pts usually young, smokers, ± other vasospastic disorders (eg, migraines, Raynaud’s)

• Most frequent between midnight and early morning when vagal tone is highest

• Provocation testing: spasm can be precipitated at angio w/ IC ergonovine or acetylchol. positive test = severe narrowing w/ sx or ECG ∆s; nonobstructive CAD typically seen; rarely done as risks include refractory/recurrent spasm or arrhythmia

• Noninvasive testing: hyperventilation, 12-lead Holter, exercise study

• Treatment: often initiated empirically without provocation testing:

high-dose CCB (dilt, verap or nifed all roughly ≈) & standing nitrates (+SL prn) ? α-blockers/statins; d/c smoking avoid high-dose ASA (can inhibit prostacyclin & worsen spasm), nonselect βB, triptans

• Cocaine-induced vasospasm: use CCB, nitrates, ASA; ? avoid βB, but data weak and labetalol appears safe (Archives 2010;170:874; Circ 2011;123:2022)

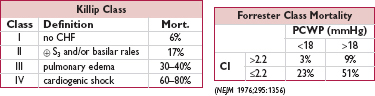

(Adapted from ACC/AHA 2007 Guideline Update for UA/NSTEMI, Circ 2007;116:e148)

• If hx and initial ECG & Tn non-dx, repeat ECG q15–30min × 1 h & Tn 3–6 h after sx onset

• If remain nl and low likelihood of ACS, search for alternative causes of chest pain

• If remain nl, have ruled out MI, but if suspicion for ACS based on hx, then still need to r/o UA w/ stress test to assess for inducible ischemia (or CTA to r/o CAD);

if low risk (eg, age ≤70; ø prior CAD, CVD, PAD; ø rest angina) can do before d/c from ED or as outPt w/in 72 h (0% mortality, <0.5% MI, Ann Emerg Med 2006;47:427)

if not low risk, admit and initiate Rx for possible ACS and consider stress test or cath

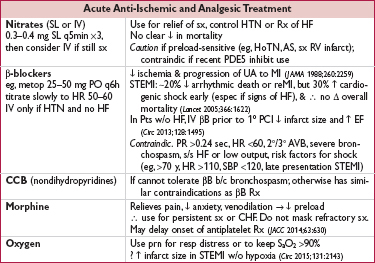

• High-intensity statin therapy (eg, atorvastatin 80 mg qd)

↓ ischemic events w/ benefit emerging w/in wks (JAMA 2001;285:1711 & JACC 2005;46:1405)

↓ peri-PCI MI (JACC 2010;56:1099); ↓ contrast-induced nephropathy (JACC 2014;63:71)

• ACEI/ARB: start once hemodynamics and renal function stable

Strong indication for ACEI if heart failure, EF <40%, HTN, DM, CKD; ∼10% ↓ mortality, greatest benefit in ant. STEMI or prior MI (Lancet 1994;343:1115 & 1995;345:669)

Start w/ low dose of short-acting (eg, captopril 6.25 mg tid), titrate up as tolerated

ARB appear ≈ ACEI (NEJM 2003;349:20); give if contraindic to ACEI

• Ezetimibe, aldosterone blockade, and ranolazine discussed later (long-term Rx)

• IABP: can be used for refractory angina when PCI not available

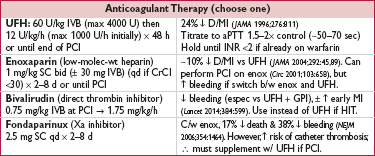

Key issues are antithrombotic regimen and invasive vs conservative strategy

• Immediate/urgent coronary angiography (w/in 2 h) if refractory/recurrent angina or hemodynamic or electrical instability

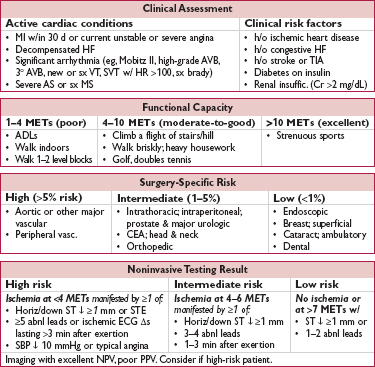

• Invasive (INV) strategy = routine angiography w/in 72 h (NEJM 2009;360:2165)

Early (w/in 24 h) if:  Tn, ST Δ, GRACE risk score (www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace) >140

Tn, ST Δ, GRACE risk score (www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace) >140

Delayed (ie, acceptable anytime w/in 72 h) if no indication for early/immediate cath but has other high-risk predictors incl: diabetes, EF <40%, GFR <60, post-MI angina, TIMI Risk Score ≥3, GRACE score 109–140, PCI w/in 6 mo, prior CABG

Invasive strategy leads to 32% ↓ rehosp for ACS, nonsignif 16% ↓ MI, no Δ in mortality c/w cons. (JAMA 2008;300:71); ↑ peri-PCI MI counterbalanced by ↓↓ in spont. MI; mortality benefit seen in some studies, likely only if cons. strategy w/ low rate of angio

↑ risk of death or MI if invasive strategy deferred beyond 72 h (JAMA 2003;290:1593)

• Conservative (CONS) strategy = selective angio. Medical Rx with pre-d/c stress test; angio only if recurrent ischemia or  ETT. Indicated for: low TIMI Risk Score, Pt or physician preference in absence of high-risk features, low-risk women (JAMA 2008;300:71).

ETT. Indicated for: low TIMI Risk Score, Pt or physician preference in absence of high-risk features, low-risk women (JAMA 2008;300:71).

Figure 1-2 Approach to UA/NSTEMI

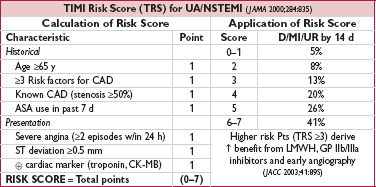

• ≥2 contiguous leads w/ ≥1 mm (except for V2–V3: ≥2 mm in  and ≥1.5 mm in

and ≥1.5 mm in  ), or

), or

• New or presumed new LBBB w/ compelling H&P, or

• True posterior MI: ST depression V1–V3 ± tall Rw w/ STE on posterior leads (V7–V9)

• Immediate reperfusion (ie, opening occluded culprit coronary artery) is critical

• In PCI-capable hospital, goal should be primary PCI w/in 90 min of 1st medical contact

• In non–PCI-capable hospital, consider transfer to PCI-capable hospital (see below), o/w fibrinolytic therapy w/in 30 min of hospital presentation. If dx confirmed, administration of fibrinolytic in ambulance prior to arrival can be considered

• Do not let decision regarding method of reperfusion delay time to reperfusion

• Definition: immediate PCI upon arrival to hospital or transfer for immediate PCI

• Indications: STE + sx onset <12 h; ongoing ischemia 12–24 h after sx onset; shock or severe HF regardless of time

• Superior to lysis: 27% ↓ death, 65% ↓ reMI, 54% ↓ stroke, 95% ↓ ICH (Lancet 2003;361:13)

• Transfer to center for 1° PCI superior to lysis (NEJM 2003;349:733). ∴ If initially seen at non-PCI capable hosp, transfer for PCI if door-in to door-out time can be ≤30 min and 1st medical contact to PCI time estimated to be ≤120 min.

• Thrombus aspiration: small study showed ↓ mortality, but larger studies show no benefit and ↑ stroke (Lancet 2008;371:1915; NEJM 2013;369:1587 & 2015;372:1389)

• Small studies have demonstrated ↓ MACE w/ complete revasc vs culprit artery alone (NEJM 2013; 369:1115; JACC 2015;65:963), large study ongoing; alternatively, could assess ischemia due to residual lesions w/ imaging stress (Circ 2011;124:e574)

Adapted from ACC/AHA 2013 STEMI Guidelines (Circ 2013;127:529)

• Indic: STE/LBBB + sx <12 h + >120 min before PCI can be performed; benefit if sx >12 h less clear; reasonable if persist. sx & STE or hemodyn instability or large territory at risk

• Fibrin-spec lytics (TNK, TPA, RPA) ↑ artery patency vs streptokinase (JACC 2013;61:e78)

• Mortality ↓ ∼20% in anterior MI or LBBB and ∼10% in IMI c/w ∅ reperfusion Rx

• Prehospital lysis (ie, ambulance): further 17% ↓ in mortality (JAMA 2000;283:2686)

• ∼1% risk of ICH; high-risk groups include elderly (∼2% if >75 y), women, low wt

• Although age not contraindic., ↑ risk of ICH in elderly (>75 y) makes PCI more attractive

• Successful reperfusion gauged by sx & ECG: sudden CP resolution & ≥70% resolution of STE indicative of successful reperfusion; conversely, STE resolution <50% after 60–90 min should prompt consideration of rescue PCI (qv)

• Facilitated or pharmacoinvasive PCI = upstream lytic, GPI or GPI + ½ dose lytic before PCI; in general no clear clinical benefit & ↑ bleeding (Lancet 2006;367:569; NEJM 2013;368:1379)

• Rescue PCI if shock, unstable, failed reperfusion or persistent sx (NEJM 2005;353:2758)

• Routine angio ± PCI w/in 24 h of successful lysis: ↓ D/MI/revasc (Lancet 2004;364:1045) and w/in 6 h ↓ reMI, recurrent ischemia, & HF compared to w/in 2 wk (NEJM 2009;360:2705);

∴ if lysed at non-PCI capable hospital, consider transfer to PCI-capable hospital ASAP espec if high-risk presentation (eg, anterior MI, inferior MI w/ low EF or RV infarct, extensive STE or LBBB, HF, ↓ BP or ↑ HR)

• Late PCI (median day 8) of occluded infarct-related artery: no benefit (NEJM 2006;355:2395)

Adapted from ACC/AHA 2013 STEMI Guidelines Update (Circ 2013;127:529); Lancet 2013;382:633

Adapted from ACC/AHA 2013 STEMI Guidelines (Circ 2013;127:529); Lancet 2013;382:633

• Inflates during diastole and deflates during systole to ↑ coronary flow and ↓ afterload

• Routine use in high-risk STEMI → ↑ stroke/bleeds w/o ∆ in survival, infarct size or EF (EHJ 2009;30:459; JAMA 2011;306:1329)

• In cardiogenic shock, no survival benefit w/ IABP if early revasc (NEJM 2012;367:1287); 18% ↓ death in Pts w/ cardiogenic shock treated with lytic (EHJ 2009;30:459)

• Diurese to achieve PCWP 15–20 → ↓ pulmonary edema, ↓ myocardial O2 demand

• ↓ Afterload → ↑ stroke volume & CO, ↓ myocardial O2 demand

can use IV NTG or nitroprusside (risk of coronary steal) → short-acting ACEI

• Inotropes if HF despite diuresis & ↓ afterload; use dopamine, dobutamine or milrinone

• Cardiogenic shock (∼7%) = MAP <60 mmHg, CI <2 L/min/m2, PCWP >18 mmHg; inotropes, mech support [eg, VAD, IABP (see above)] to keep CI >2; pressors to keep MAP >60; if not done already, coronary revasc (NEJM 1999;341:625)

• Heart block (∼20%, occurs because RCA typically supplies AV node) 40% on present., 20% w/in 24 h, rest by 72 h; high-grade AVB can develop abruptly Rx: atropine, epi, aminophylline (100 mg/min × 2.5 min), temp pacing wire

• RV infarct (proximal RCA occlusion → compromised flow to RV marginal branch) Angiographically in 30–50%, but only ½ of those clinically signif.

HoTN; ↑ JVP,  Kussmaul’s; 1 mm STE in V4R; RA/PCWP ≥0.8; RV dysfxn on TTE

Kussmaul’s; 1 mm STE in V4R; RA/PCWP ≥0.8; RV dysfxn on TTE

Rx: optimize preload (RA goal 10–14, BHJ 1990;63:98); ↑ contractility (dobutamine); maintain AV synchrony (pacing as necessary); reperfusion (NEJM 1998;338:933); mechanical support (IABP or RVAD); pulmonary vasodilators (eg, inhaled NO)

• Free wall rupture: ↑ risk w/ lysis, large MI, ↑ age,  , HTN; p/w PEA or hypoTN, pericardial sx, tamponade; Rx: volume resusc., ? pericardiocentesis, inotropes, surgery

, HTN; p/w PEA or hypoTN, pericardial sx, tamponade; Rx: volume resusc., ? pericardiocentesis, inotropes, surgery

• VSD: large MI in elderly; AMI → apical VSD, IMI → basal septum; 90% w/ harsh murmur ± thrill (NEJM 2002;347:1426); Rx: diuretics, vasodil., inotropes, IABP, surgery, perc. closure

• Papillary muscle rupture: more common after inf MI (PM pap. muscle supplied by PDA alone) than ant MI (AL pap. muscle supplied by diags & OMs); 50% w/ new murmur, rarely a thrill, ↑ v wave in PCWP tracing; asymmetric pulmonary edema on CXR (often worse in RUL due to direction of jet). Rx: diuretics, vasodilators, IABP, surgery.

• Treat as per ACLS for unstable or symptomatic bradycardias & tachycardias

• AF (10–16% incidence): βB or amio, ± digoxin (particularly if HF), heparin

• VT/VF: lido or amio × 6–24 h, then reassess; ↑ βB as tol., replete K & Mg, r/o ischemia; early monomorphic (<48 h post-MI) does not carry bad prognosis. Beyond 48 h, VT/VF a/w worse prognosis → consider wearable defibrillator (qv).

• Accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR): slow VT (<100 bpm), often seen after successful reperfusion; typically self-terminates and does not require treatment

• May consider backup transcutaneous pacing (TP) if: 2° AVB type I, BBB

• Backup TP or initiate transvenous pacing if: 2° AVB type II; BBB + AVB

• Transvenous pacing (TV) if: 3° AVB; new BBB + 2° AVB type II; alternating LBBB/RBBB (can bridge w/ TP until TV, which is best accomplished under fluoroscopic guidance)

• In registries, in-hospital mortality is 6% w/ reperfusion Rx (lytic or PCI) and ∼20% w/o

• Predictors of mortality: age, time to Rx, anterior MI or LBBB, heart failure (Circ 2000;102:2031)

(Am J Cardiol 1967;20:457)

(JAMA 2001;286:1356)

• Stress test if anatomy undefined; consider stress if signif residual CAD post-PCI of culprit

• Assess LVEF prior to d/c; EF ↑ ∼6% in STEMI over 6 mo (JACC 2007;50:149)

• Aspirin: 81 mg daily

• P2Y12 inhib (ticagrelor or prasugrel preferred over clopi): treat for at least 12 mo

Prolonged Rx beyond 12 mo → ↓ CV death, MI, & stroke (& stent thrombosis) w/ ↑ in bleeding, but no ↑ fatal bleeding or ICH. For Rx beyond 1st 12 mo, comparable efficacy w/ ticagrelor 90 or 60 mg bid, better safety & tolerability with 60 bid (NEJM 2015;372:1791; JACC 2007;49:1982 & 2015;65:2211).

Some PPIs interfere w/ biotransformation of clopi and ∴ plt inhibition, but no convincing impact on clinical outcomes (Lancet 2009;374:989; NEJM 2010;363:1909); use w/PPIs if h/o GIB or multiple GIB risk factors (JACC 2010;56:2051)

• β-blocker: 23% ↓ mortality after MI

• Statin: high-intensity lipid-lowering (eg, atorvastatin 80 mg, NEJM 2004;350:1495)

• Ezetimibe: ↓ CV events including MI and ischemic stroke when added to statin (IMPROVE-IT, NEJM 2015;372:1500)

• ACEI: lifelong if HF, ↓ EF, HTN, DM; 4–6 wk or at least until hosp. d/c in all STEMI

? long-term benefit in CAD w/o HF (NEJM 2000;342:145 & 2004;351:2058; Lancet 2003;362:782)

• Aldosterone antag: 15% ↓ mortality if EF <40% & either s/s of HF or DM; contraindic if renal dysfxn (Cr >2.5 in men, >2 in women) or K >5 (NEJM 2003;348:1309)

• Nitrates: standing if symptomatic; SL NTG prn for all

• Ranolazine: inhibits late inward Na current, prevents intracellular Ca overload; ↓ recurrent ischemia (JAMA 2007;297:1775)

• Oral anticoagulants: if warfarin needed in addition to ASA/clopi (eg, AF or LV thrombus), target INR 2–2.5. ? stop ASA if at high bleeding risk on triple Rx (Lancet 2013;381:1107). Not FDA approved: low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg bid) in addition to ASA & clopi → 16% ↓ D/MI/stroke and 32% ↓ all-cause death, but ↑ major bleeding and ICH (NEJM 2012;366:9).

• NSAIDs/COX2 inhib relatively contraindic b/c ? ↑ death, MI, HF, rupture (Circ 2006;113:2906)

• If sust. VT/VF >2 d post-MI not due to reversible ischemia; consider wearable defibrillator or ICD (JACC 2014;130:94)

• Indicated in 1° prevention of SCD if post-MI w/ EF ≤30–40% (NYHA II–III) or ≤30–35% (NYHA I); need to wait ≥40 d after MI (NEJM 2004;351:2481 & 2009;361:1427)

• Low chol. (<200 mg/d) & fat (<7% saturated) diet; ? Ω-3 FA

• Traditional LDL-C goal <70 mg/dL; new recs w/o LDL-C target, rather simply high-intensity statin; may change w/ IMPROVE-IT trial showing that lower is better (lower CV event rate in arm with achieved LDL-C of 54 vs 70 mg/dL)

• BP <140/90 and consider <130/80 mmHg (HTN 2015;65:1372); smoking cessation

• If diabetic, tailor HbA1c goal based on Pt (avoid TZDs if HF)

• Exercise (30–60 min 5–7×/wk); cardiac rehab; BMI goal 18.5–24.9 kg/m2

• Influenza & pneumococcal vaccination (Circ 2006;114:1549; JAMA 2013;310:1711); screen for depression

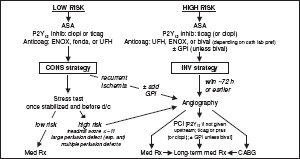

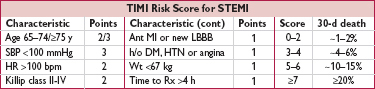

Goal: characterize risk of Pt & procedure → appropriate testing (ie, results will Δ management) and interventions (ie, reasonable probability of ↓ risk of MACE)

• Clinical assessment: evidence of active cardiac disease and/or risk factors

• Functional capacity (METs)

• Surgery-specific risk

• Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI): 6 risk factors = 5 clinical risk factors above and type of surgery (intrathoracic, intra-abd, or suprainguinal vascular) (Circ 1999;100:1043) # of risk factors predicts risk of MACE: ≤1 RF → <1%, 2 RFs → 6.6%, ≥3 RFs → 11%

• Comorbidity indices (eg, Charlson index) may predict mortality (Am J Med Qual 2011;26:461)

• ECG if known cardiac disease and possibly reasonable in all, except if low-risk surgery

• TTE if any of the following and prior TTE >12 mo ago or prior to Δ in sx:

dyspnea of unknown origin

hx of HF w/ ↑ dyspnea

suspected valvular disease (eg, murmur on exam)

≥moderate stenosis/regurg

• Stress test (usually pharmacologic) if:

active cardiac issues where stress testing is indicated (qv), or

not low-risk surgery, RCRI ≥2, poor or unknown fxnal capacity, and results will Δ mgmt (ie, modify or delay surgery, undergo coronary revascularization, etc.)

overall low PPV to predict periop CV events

• Angiography: based on noninvasive stress results for standard indications, although systematic angio ↓ 2–5 y mortality in Pts undergoing vascular surgery (JACC 2009;54:989)

• ? consider CXR & ECG in preop evaluation of severely obese Pts (Circ 2009;120:86)

• If possible, wait ∼60 d after MI in the absence of revascularization before elective surgery

• After PCI: delay elective surgery 14 d after balloon angioplasty, 30 d after BMS implantation, and ideally 6 mo after DES implantation

• Coronary revascularization should be based on standard indications (eg, ACS, refractory sx, lg territory at risk). Has not been shown to Δ risk of death or postop MI when done prior to elective vasc. surgery based on perceived cardiac risk (NEJM 2004;351:2795) or documented extensive ischemia (AJC 2009;103:897).

• Decompensated HF should be optimally treated prior to elective surgery

• ↓ EF (<30%) associated with poor outcomes

• 30-d CV event rate: symptomatic HF > asx HFrEF > asx HFpEF > no HF

• If meet criteria for valve intervention (qv), do so before elective surgery (postpone if necessary)

• If severe valve disease and surgery urgent, intra- & postoperative hemodynamic monitoring reasonable (espec for AS, since at ↑ risk even if sx not severe; be careful to maintain preload, avoid hypotension, and watch for atrial fibrillation)

• If severe AS and Pt not eligible for or impractical to do AVR prior to noncardiac surgery, balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) can be considered but not routinely recommended (Circ 2008;118:e523)

• Includes PPM, CRT, ICD

• Should be discussion between surgical team & CIED team regarding: need for device (eg, complete heart block) & consequences if interference w/ fxn likelihood of electromagnetic interference consideration of reprogramming, magnet use, etc.

• ASA: continue in Pts w/ existing indication. Initiation just prior to surgery does not ↓ 30-d ischemic events and ↑ bleeding (NEJM 2014;370:1494), but Pts w/ recent stents excluded.

• Dual antiplatelet therapy in Pts undergoing urgent surgery: continue 4–6 wk after PCI (BMS or DES) unless risk of bleeding > benefit of prevention of stent thrombosis. If must discontinue ADP receptor blocker, continue ASA and restart ADP receptor blocker ASAP.

• β-blockers (Circ 2009;120:2123; JAMA 2010;303:551; Am J Med 2012;125:953)

Continue βB in Pts on them chronically. Do not discontinue βB abruptly postop, as may cause sympathetic activation from withdrawal. Use IV agents peri-operatively if Pt unable to take PO.

In terms of initiating βB, conflicting evidence; may depend on how administered. Some studies show ↓ death & MI (NEJM 1996;335:1713 & 1999;341:1789), another showed ↓ MI, but ↑ death & stroke and ↑ bradycardia/HoTN (Lancet 2008;371;1839).

? consider initiating if intermed- or high-risk  stress test, or RCRI ≥3, espec if vasc surgery

stress test, or RCRI ≥3, espec if vasc surgery

Ideally initiate at least 1 wk prior to surgery, use low-dose, short-acting βB, and titrate slowly and carefully to achieve desired individual HR and BP goal (? HR ∼55–65). Avoid bradycardia and HoTN.

• Statins: ↓ ischemia & CV events in Pts undergoing vascular surg (NEJM 2009;361:980); may reduce AF, MI, LOS in statin-naïve Pts (Arch Surg 2012;147:181). Consider in Pts w/ a clinical risk factor undergoing non–low-risk surgery.

• ACEI/ARB: may cause HoTN perioperatively. If held before surgery, restart ASAP.

• Amiodarone: ↓ incidence of postop AF

oral (eg, 600 mg qd × 7 d preop, then 200 mg qd until discharge) & IV regimens equivalent but effective only if initiated ≥1 d prior to surgery (Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2013;36:1017)

cardiac surgery: ↓ postop AF, length of stay & cost (NEJM 1997;337:1785)

thoracic surgery: ↓ postop AF but not length of stay or cost (J Thorac CV Surg 2010;140:45; Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:339; Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:120). Not advised if severe lung disease or undergoing pneumonectomy (Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1144).

• ✓ Postop ECG if known CAD or high-risk surgery. Consider if >1 risk factor for CAD.

• ✓ Postop troponin only if new ECG Δs or chest pain suggestive of ACS. Elevated Tn postop predicts mortality, but may simply be a marker for underlying CAD (Annals 2011;154:523; JAMA 2012;307:2295). Routine ✓ postop in all Pts (even just high-risk Pts) has not been proven to modify outcomes and it is not routinely recommended.