• Prevalence 33.5% in U.S. adults; >75 million affected (prevalence equal for men and women, highest in African American adults at 44%)

• ↑ Age → ↓ arterial compliance → systolic HTN

• Only 48% of patients with dx of HTN have adequate BP control

• Essential (95%): onset 25–55 y;  FHx. Unclear mechanism but ? additive microvasc renal injury over time w/ contribution of hyperactive sympathetics (NEJM 2002;346:913).

FHx. Unclear mechanism but ? additive microvasc renal injury over time w/ contribution of hyperactive sympathetics (NEJM 2002;346:913).

Both genetic (Nature 2011;478:103) & environmental risk factors (Na, obesity, inactivity)

Blacks more likely to be salt sensitive and have less activation of renin-angiotensin system, explaining preference for thiazides & CCB over ACEI or ARB

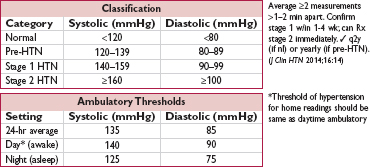

• Secondary: Consider if Pt <20 or >50 y or if sudden onset, severe, refractory HTN

• Goals: (1) identify CV risk factors or other diseases that would modify prognosis or Rx; (2) reveal 2° causes of hypertension; (3) assess for target-organ damage

• History: CAD, HF, TIA/CVA, PAD, DM, renal insufficiency, sleep apnea, preeclampsia;  FHx for HTN; diet, Na intake, smoking, alcohol, prescription and OTC meds, OCP

FHx for HTN; diet, Na intake, smoking, alcohol, prescription and OTC meds, OCP

• Physical exam: ✓ BP in both arms; funduscopic exam; BMI & waist circumference; cardiac (LVH, murmurs) including signs of HF, vascular (bruits, radial-femoral delay); abdominal (masses or bruits); neuro exam

• Testing: K, BUN, Cr, Ca, glc, Hct, U/A, lipids, TSH, urinary albumin:creatinine (if ↑ Cr, DM, or peripheral edema), ? renin, ECG (for LVH), CXR, TTE (eval for valve abnl, LVH)

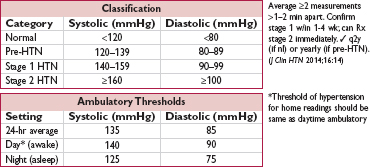

• Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM): predictive of CV risk and ↑ Se & Sp for dx of HTN vs office BP (HTN 2005;46:156). Consider for suspected episodic or white coat HTN, resistant HTN, HoTN sx on meds, or suspected autonomic dysfxn. Rec by some guidelines to confirm HTN dx, so utilization may expand (BMJ 2011;342:d3621 & 343:d4891).

• Each ↑ 20 mmHg SBP or 10 mmHg DBP → 2× ↑ CV complications (Lancet 2002;360:1903)

• Neurologic: TIA/CVA, ruptured aneurysms, vascular dementia

• Retinopathy: stage I = arteriolar narrowing; II = copper wiring, AV nicking; III = hemorrhages and exudates; IV = papilledema

• Cardiac: CAD, LVH, HF, AF

• Vascular: aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm (HTN = key risk factor for aneurysms)

• Renal: proteinuria, renal failure

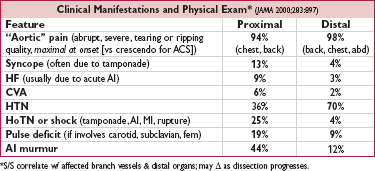

• Goal: in general, <140/90 mmHg

In elderly: data sparser, but benefit, albeit w/ less strict BP target (NEJM 2008;358:1887); thus, consider <150/90 mmHg if either (a) ≥80 y and w/o DM or CKD (ASH/ISH rec), or (b) ≥60 y (but no need to downtitrate if <140/90 & tolerating meds) (JNC 8 rec)

In Pts w/ prior MI or stroke: reasonable to consider <130/80 (HTN 2015;65:1372)

In Pts w/ DM and/or CKD: prior targets of <130/80 not supported by data (and harm if target <120; NEJM 2010;362:1575), but may consider if CKD & albuminuria for renal protection (ASH/ISH rec based on NEJM 1994;330:877)

• Treatment results in 50% ↓ HF, 40% ↓ stroke, 20–25% ↓ MI (Lancet 2014;384:591)

• Lifestyle modifications (each ↓ SBP ∼5 mmHg)

weight loss: goal BMI 18.5–24.9; aerobic exercise: ≥30 min exercise/d, ≥5 d/wk

diet: rich in fruits & vegetables, low in saturated & total fat (DASH, NEJM 2001;344:3)

sodium restriction: ≤2.4 g/d and ideally ≤1.5 g/d (NEJM 2010;362:2102)

maintain adequate potassium intake through diet counseling (∼120 mEq of dietary potassium) if no predisposition to hyperkalemia (NEJM 2007;356:1966)

limit alcohol consumption: ≤2 drinks/d in  ; ≤1 drink/d in

; ≤1 drink/d in  & lighter-wt Pts

& lighter-wt Pts

avoid exacerbating exposures (eg, NSAID use)

• Pharmacologic options for HTN or pre-HTN w/ comorbidity (nb, pre-HTN w/o DM, CKD, CV disease, or other end organ dysfunction treated w/ lifestyle alone)

Pre-HTN: ARB prevents onset of HTN, no ↓ in clinical events (NEJM 2006;354:1685)

HTN: choice of therapy controversial, concomitant disease and stage may help guide Rx

uncomplicated: CCB, ARB or ACEI, or thiazide (chlorthalidone preferred) are 1st line (NEJM 2009;361:2153); βB not 1st line (Lancet 2005;366:1545).

For non-black Pts <60 y: reasonable to start w/ ARB or ACEI, then add CCB or thiazide if needed, and then add remaining class if still needed

For black, elderly, and ? obese Pts (all of whom more likely to be salt sensitive): reasonable to start with CCB or thiazide, then add either the other 1st choice class or ARB or ACEI if needed, and then all 3 classes if still needed

+CAD (Circ 2015;131:e435): ACEI or ARB (NEJM 2008;358:1547); ACEI+CCB superior to ACEI+thiazide (NEJM 2008;359:2417) or βB+diuretic (Lancet 2005;366:895); may require βB and/or nitrates for anginal relief; if h/o MI, βB ± ACEI/ARB ± aldo antag (see “ACS”)

+HF: ACEI/ARB, βB, diuretics, aldosterone antagonist (see “Heart Failure”)

+2° stroke prevention: ACEI (Lancet 2001;358:1033); ? ARB (NEJM 2008;359:1225)

+diabetes mellitus: ACEI or ARB; can also consider thiazide or CCB

+chronic kidney disease: ACEI or ARB (NEJM 1993;329:1456 & 2001;345:851 & 861)

• Tailoring therapy

lifestyle Δs typically complementary rather than alternative to drug Rx [although if low risk (stage 1, no end-organ damage or risk factors), could start with lifestyle]

if stage 1, start w/ monoRx; if stage 2, consider starting w/ combo (eg, ACEI + CCB; NEJM 2008;359:2417), as most will require ≥2 drugs

typically start drug at 1⁄2 maximal dose; after 2–3 wk either titrate up or add new drug

• BP > goal on ≥3 drugs incl diuretic, ∼12–13% of hypertensive population (HTN 2011;57:1105)

• Differentiate between true & pseudoresistance, w/ latter due to:

inaccurate measurement or use of wrong cuff size

poor dietary compliance (Na/K intake, can assess w/ 24-hr urine for Na, K and Cr)

suboptimal med dosing (eg, <50% of max dose) or poor med compliance

volume expansion (inadequate diuretic dosing)

white coat HTN (consider ABPM)

2° causes or external drivers (eg, OSA, steroids, NSAIDS, alcohol) (Lancet 2010;376:1903)

• True resistance = uncontrolled BP confirmed by ABPM despite compliance w/ optim. doses

• Treatment considerations:

Persistent ↑ volume may contribute even if on standard HCTZ (Archives 2008;168:1159). Effective diuretic dosing required for most to achieve control (HTN 2002;39:982). Chlorthalidone over HCTZ (if renal function preserved). Loop diuretic favored over thiazide for initial Rx if eGFR <30; however, adding thiazide to loop can ↑ diuresis if insufficient response to loop alone.

Adding aldosterone antagonist (if renal function preserved) (PATHWAY-2, ESC 2015)

Adding β-blocker (particularly vasodilating ones such as labetalol, carvedilol, or nebivolol), centrally acting agent, α-blocker, or direct vasodilator

Other Rx under investigation: renal denervation (see below); carotid baroreceptor stimulation; central AV anastomosis ↓ SBP by ∼23 mmHg (Lancet 2015;385:1634)

• Renal denervation: catheter-based RF ablation of renal nerves modifying sympathetic outflow. Had appeared beneficial in unblinded and/or uncontrolled studies, but no effect on BP in controlled trial, so not currently an option in routine care (NEJM 2014;370:1393).

• Secondary causes

Renovascular (qv)

Renal parenchymal disease: salt and fluid restriction, ± diuretics

Endocrine etiologies: see “Adrenal Disorders”

• Pregnancy: methyldopa, labetalol, nifedipine, hydralazine; avoid diuretics;  ACEI/ARB

ACEI/ARB

• Hypertensive emergency: ↑ BP → acute target-organ ischemia and damage

neurologic: encephalopathy (insidious onset of headache, nausea, vomiting, confusion), hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, papilledema

cardiac: ACS, HF/pulmonary edema, aortic dissection

renal: proteinuria, hematuria, acute renal failure; scleroderma renal crisis

microangiopathic hemolytic anemia; preeclampsia-eclampsia

• Hypertensive urgency (severe asymptomatic HTN): SBP >180 or DBP >120 (?110) w/ minimal or no target-organ damage

• Progression of essential HTN ± medical noncompliance (espec clonidine) or Δ in diet

• Progression of renovascular disease; acute glomerulonephritis; scleroderma; preeclampsia

• Endocrine: pheochromocytoma, Cushing’s

• Sympathomimetics: cocaine, amphetamines, MAO inhibitors + foods rich in tyramine

• Cerebral injury: do not treat HTN in acute ischemic stroke unless Pt getting lysed, extreme

BP (>220/120), Ao dissection, active ischemia or HF (Stroke 2003;34:1056)

• Tailor goals to clinical context (eg, more rapid lowering for Ao dissection)

• Emergency: ↓ MAP by ∼25% in mins to 2 h w/ IV agents (may need arterial line for monitoring); goal DBP <110 w/in 2–6 h, as tolerated

• Urgency: ↓ BP to ≤160/100 in hrs using PO agents; goal normal BP in ∼1–2 d

• Watch UOP, Cr, mental status: may indicate a lower BP is not tolerated

• ↓ renal perfusion → activation of RAA system → vasoconstriction, ↑ aldo & vasopressin, ↑ sympathetic activity → volume retention & HTN → progressive renal dysfxn and CV risk

• Unilateral stenosis → HTN

• Bilateral (or unilat involving solitary functioning kidney) → HTN & progressive renal insuffic

• Atherosclerosis (∼90%): usually involving ostial or prox segments. Often incidental finding as common in Pts w/ established athero (eg, CAD, PAD) but uncommon cause of HTN.

• Fibromusclar dysplasia (FMD, ∼10%): nonathero medial fibroplasia usually mid/distal female-predominant (85-90%); mean age 52 y (Circ 2012;125:3182)

characteristic “string of beads” appearance (or concentric smooth stenosis) on angio

usually >1 territory involved (eg, carotid in ∼65%), explaining sx of HA, dizziness, tinnitus

• Other (uncommon): vasculitis (Takayasu’s, GCA, PAN or eosinophilic granulomatosis w/ polyangiitis) often w/ ↑ inflammatory markers, systemic s/s; scleroderma; local aneurysm or dissection; embolism; retroperitoneal fibrosis

• Consider testing if any of the following and if finding would modify treatment:

Clinical picture consistent w/ secondary HTN w/ no other compelling etiology

Severe HTN (SBP ≥180 and/or DBP ≥120 mmHg) and/or flash pulm edema/CHF

Progressive renal insufficiency w/ bland sediment, unilateral small kidney (≤9 cm), renal asymmetry >1.5 cm, or acute sustained Cr ↑ by ≥30% w/in 1 wk of starting ACEI/ARB

• Monitoring: for athero, repeat imaging only necessary if Δ in clinical status that would lead to intervention; for FMD image q6–12mo to assess for progression

• If due to atherosclerosis, risk factor modification: quit smoking, ↓ chol

• Antihypertensive Rx effective for most Pts: diuretic + ACEI/ARB (watch for ↑ Cr) or CCB

• Revascularization (typically percutaneous w/ stenting):

Had considered if refractory HTN, recurrent flash pulm edema, worsening CKD

However, clinical trials enrolling stable Pts w/ mod stenosis (50–70%) and HTN on ≥2 agents showed no benefit on # of BP meds, renal fxn or CV outcomes (NEJM 2000;342:1007; 2009;361:1953; 2014;370:13). Unknown if beneficial in more severe stenoses or in higher-risk Pts (eg, recent CHF, >3 meds).

Resistive index >80 on U/S implies intrinsic renal damage and thus less likely to benefit from revasc, so may predict outcome after intervention (NEJM 2001;344:410). Operator dependent and some studies have not replicated findings, so not utilized broadly.

Renal vein renin measurements, PRA, captopril renogram may provide supportive evidence as to hemodynamic significance of RAS, but limited utility due to low Se

For FMD (usually more distal lesions): PTA ± bailout stenting

• Surgery (very rare): resection of pressor kidney

• Bilateral RAS: 20–46% of Pts w/ RAS. Associated w/ higher creatinine and worse CV outcomes. In addition to anti-HTN Rx, consider revasc if likely to benefit (failure of meds, recurrent pulmonary edema, progressive renal failure). Trials including Pts w/ bilateral RAS did not show benefit but included moderate stenoses.

• True aneurysm (≥50% dilation of all 3 layers of aorta; <50% called ectasia) vs false or pseudoaneurysm (rupture contained by adventitia)

• Location: root (annuloaortic ectasia), thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA), thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA), abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

• Type: fusiform (circumferential dilation) vs saccular (localized dilation of aortic wall)

• In U.S., ∼15,000 deaths/y from aortic ruptures; overall ∼50,000 deaths/y from Ao disease

• TAA: 10/100,000 Pt-yrs,  :

: 2:1; ∼60% root/ascending; 40% descending

2:1; ∼60% root/ascending; 40% descending

• AAA: ∼4–8% prev in those >60 y (although may be ↓; Circ 2011;124:1118); 4–6× more common in  vs

vs  ; mostly infrarenal

; mostly infrarenal

• Arch & TAAA rarer

• Medial degeneration and/or ↑ wall stress

Medial degeneration = muscle apoptosis, elastin fiber weakening, mucoid infiltration

Wall stress ∝ [(ΔP × r) / (wall thickness)], LaPlace’s law

• TAA: most commonly medial degeneration; seen w/ connective tissue disorders & aortitis

• AAA: most commonly long-standing HTN + athero/inflammation → medial weakening

• Classic: HTN, atherosclerosis, smoking, age, male sex

• Marfan syndrome (mutations in fibrillin-1, FBN-1): cardinal features are Ao root aneurysm & ectopia lentis. Other suggestive signs include: tall stature; arachnodactyly w/ thumb sign (entire distal phalanx of adduct. thumb extends beyond ulnar border of palm) and/or wrist sign (tip of thumb covers 5th finger fingernail when wrapped around contralat wrist); pectus deformities; scoliosis; dural ectasia; spontaneous PTX; MVP.

• Loeys-Dietz syndrome (mutation in TGF-β receptors 1 or 2, TGFBR1/2): triad of arterial tortuosity & aneurysms, widely spaced eyes, bifid uvula or cleft palate. Also w/ velvety & hyperlucent skin and bluish sclera.

• Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (mutation in type III procollagen, COL3A1): easy bruising; thin, translucent skin w/ visible veins (but not excessively stretchable); acrogeria (aged appearance of hands & feet); flexible digits; uterine or intestinal rupture; distinctive facial features (protruding eyes, thin nose & lips, sunken cheeks, small chin)

• Other genetic disorders: bicuspid AoV; Turner syndrome (45X; short stature, ovarian failure, Ao coarctation); other familial aortopathies (mutations in smooth muscle myosin & actin genes including MYH11 and ACTA2)

• Aortitis: Takayasu’s, GCA, spondyloarthritis, IgG4-related disease

• Infection (ie, mycotic aneurysm): salmonella, TB, syphilis

• TAA: if bicuspid AoV or 1° relative w/: (a) TAA or bicuspid valve, (b) Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, Turner; known relevant genetic mutation (see above)

• AAA: ✓ for pulsatile abd mass; U/S  >60 y w/ FHx of AAA &

>60 y w/ FHx of AAA &  65–75 y w/ prior tobacco

65–75 y w/ prior tobacco

• Contrast CT: quick, noninvasive, high Se & Sp for all aortic aneurysms

• TTE/TEE: TTE most useful for root and proximal Ao; TEE can visualize other sites of TAA

• MRI: preferred over CT for aortic root imaging for TAA; also useful in AAA but time-consuming; noncontrast “black blood” MR to assess aortic wall

• Abdominal U/S: screening and surveillance test of choice for infrarenal AAA

• Goal is to prevent rupture (50% mortality prior to hospital) by modifying risk factors

• Smoking cessation: smoking associated w/ ↑ rate of expansion (Circ 2004;110:16)

• Statin (to achieve LDL-C <70 mg/dL): ↓ death and stroke & possibly ↓ rate of expansion (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;32:21)

• BP control: βB (↓ dP/dt) ↓ aneurysm growth (NEJM 1994;330:1335)

ACEI a/w ↓ risk of rupture (Lancet 2006;368:659)

ARB may ↓ rate of aortic root growth in Marfan (NEJM 2008;358:2787)

βB and ARB similar ↓ rate of Ao root growth in children and young adults w/ Marfan (NEJM 2014;371:2061)

• Moderate cardiovascular exercise okay, but no burst activity/exercise requiring Valsalva maneuvers (eg, heavy lifting)

• Indications for intervention (surgery/endovascular repair)

Individualize based on FHx, body size, gender, anatomy, surgical risk

TAA (Circ 2010;121:1544 & e266)

symptoms

ascending Ao ≥5.5 cm (4–5 cm if Marfan, bicuspid AoV, Loeys-Dietz, vascular EDS, or other genetic/familial disorder)

descending >6 cm

↑ >0.5 cm/y

aneurysm >4.5 cm and planned AoV surgery

AAA (NEJM 2002;346:1437 & 2014;371:2101)

symptoms

infrarenal ≥5.5 cm, but consider ≥5.0 cm in

↑ >0.5 cm/y; inflam/infxn

• Ascending aorta

No root involvement: resection & replacement w/ Dacron tube graft

Root involvement: need to address AoV integrity; depending on AoV itself: modified Bentall: Dacron Ao root + prosthetic AoV, reattach coronaries valve-sparing: reimplant native AoV in Dacron Ao graft; reattach coronaries

• Arch: high-risk, complex surgery because of the arch branches; variety of combinations of partial/complete resection, stent graft & bypass of arch vessels

• Descending thoracic aorta: resection & grafting vs endovascular repair (qv)

• Depends on favorable aortic anatomy

• TEVAR (thoracic EVAR) for descending TAA ≥5.5 cm may ↓ periop morbidity and possibly mortality (Circ 2010;121:2780; JACC 2010;55:986; J Thorac CV Surg 2010;140:1001 & 2012;144:604)

• AAA

Guidelines support open repair or EVAR for infrarenal AAA in good surg candidates

↓ short-term mort., bleeding, LOS; but long-term graft complic. (3–4%/y; endoleak, need for reintervention, rupture) necessitate periodic surveillance, with no proven Δ in overall mortality in trials, except ? in those <70 y (NEJM 2010;362:1863, 1881 & 2012;367:1988)

In observational data, EVAR assoc w/ ↑ survival over 1st 3 y, after which survival similar. Rates of rupture over 8 y 5.4% w/ EVAR vs 1.4% w/ surgery (NEJM 2015;373:328)

In Pts unfit for surgery or high periop risks: ↓ aneurysm-related mortality but no Δ in overall mortality over medical Rx (NEJM 2010;362:1872). EVAR noninferior (? superior) to open repair in ruptured AAA w/ favorable anatomy (Ann Surg 2009;250:818).

• Pt selection for endovascular includes requirement to comply with long-term surveillance

• Pain: gnawing chest, back or abdominal pain; new or worse pain may signal rupture

• Rupture: risk ↑ w/ diameter,  , current smoking, HTN

, current smoking, HTN

TAA: ∼2.5%/y if <6 cm vs 7%/y if >6 cm

AAA: ∼1%/y if <5 cm vs 6.5%/y if 5–5.9 cm

rupture p/w severe constant pain and hemorrhagic shock; ∼80% mortality at 24 h

• Aortic insufficiency (TAA) and CHF

• Acute aortic syndromes (qv)

• Thromboembolic ischemic events (eg, to CNS, viscera, extremities)

• Compression of adjacent structures (eg, SVC, trachea, esophagus, laryngeal nerve)

• Expansion rate ∼0.1 cm/y for TAA, ∼0.3–0.4 cm/y for AAA

• AAA: <4 cm q2–3 yrs; 4–5.4 cm q6–12 mos; more frequent if rate of expansion >0.5 cm in 6 mo

• TAA: 6 mo after dx to ensure stable, and if stable, then annually (Circ 2005;111:816)

• Screen for CAD, PAD and aneurysms elsewhere, espec popliteal. About 25% of Pts w/ TAA will also have AAA, and 25% of AAA Pts will have a TAA: consider pan-Ao imaging.

• Patients with endovascular repair require long-term surveillance for endoleak & to document stability of aneurysm

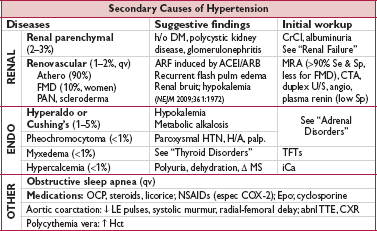

• Aortic dissection (AoD): intimal tear → blood extravasates into Ao media (creates false lumen). Rate 3–16/100,000 Pt-yrs. False lumen acts as “wind sock,” ↑ in size and compressing true lumen (patency of false lumen associated with outcome).

• Intramural hematoma (IMH): vasa vasorum rupture → medial hemorrhage that does not communicate with aortic lumen; 6% of aortic syndromes; clinically managed as AoD

• Penetrating ulcer (PAU): atherosclerotic plaque penetrates elastic lamina → medial hemorrhage. PAU in setting of IMH assoc. w/ similar outcomes as AoD. Outcomes for isolated PAU less well defined but considered AAS. Rx depends on clinical context.

• Proximal: involves ascending Ao, regardless of origin (= Stanford A, DeBakey I & II)

• Distal: involves descending Ao only, distal to L subclavian art. (= Stanford B, DeBakey III)

• Other Considerations: isolated to arch generally treated as proximal; distal with involvement of subclavian depends on overall clinical picture.

• Classic (in older Pts): hypertension (h/o HTN in >70% of dissections); age (60s–70s), male sex (∼70%  ); smoking

); smoking

• Genetic or acquired predisposition (may present younger; see “Aortic Aneurysms”):

Connective tissue disease/congenital anomaly: Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, vascular Ehlers-Danlos, bicuspid AoV, coarctation (eg, in Turner’s), other familial aortopathies, PCKD

Aortitis: Takayasu’s, GCA, Behçet’s, syphilis

Pregnancy: typically 3rd trimester

• Other environmental factors:

Trauma: blunt, deceleration injury

Cardiovascular procedures: IABP, cardiac or aortic surgery, cardiac catheterization

Acute ↑ BP: cocaine, Valsalva (eg, weightlifting)

• H&P, including bilateral BP and radial pulses for symmetry

High-risk conditions: Marfan, CTD, FHx AoD, recent Ao manip., AoV dis., Ao aneurysm

High-risk pain features: chest, back or abd pain described as [both (abrupt onset or severe intensity) and (ripping, tearing, sharp or stabbing) (absence  LR 0.3)]

LR 0.3)]

High-risk exam features:

perfusion deficit [pulse deficit ( LR 5.7), systolic BP differential (>20 mmHg), or focal neuro deficit + pain (

LR 5.7), systolic BP differential (>20 mmHg), or focal neuro deficit + pain ( LR >6)], or

LR >6)], or

murmur of AI (new or not known to be old and in conjunction w/ pain), or

hypotension or shock

• 12-lead ECG: often abnl but non-dx; may show STE if prox AoD involving coronary

• CXR: abnl in 60–90% [↑ mediast. (absence  LR 0.3), L pl effusion] but cannot r/o AoD

LR 0.3), L pl effusion] but cannot r/o AoD

• Obtain expedited Ao imaging if: ≥2 high-risk features, 1 high-risk feature w/o clear alternative dx, or 0 features but unexplained HoTN or widened mediastinum on CXR

• CT: quick, noninvasive, readily available, Se ≥93% & Sp 98%; however, if  & high clin. suspicion → additional studies (2/3 w/ AoD have ≥2 studies; AJC 2002;89:1235)

& high clin. suspicion → additional studies (2/3 w/ AoD have ≥2 studies; AJC 2002;89:1235)

• MRI: Se & Sp >98%, but time-consuming test & not readily available

• Axial studies (CT, MRI) should be gated to ECG to evaluate Ao root; if high index of suspicion, study should include entire aorta (chest, abd, & pelvis)

• Echo

TTE: low Se (∴ not dx study) but can show effusion, AI, & dissection flap (if proximal)

TEE: Se >95% prox, 80% for distal; can assess cors/peric/AI; “blind spot” behind trachea

• Aortography: Se ∼90%, time-consuming, cannot detect IMH; can assess branch vessels

• D-dimer: Se/NPV ∼97%; ? <500 ng/mL to r/o dissec (Circ 2009;119:2702) but not in Pts at high clinical risk (doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.02.013); does not r/o IMH

• ↓ dP/dt targeting HR <60 & central BP <120 (or lowest that preserves perfusion; r/o pseudohypotension, eg, arm BP ↓ due to subclavian dissection; use highest BP reading)

• First with IV βB (eg, esmolol, labetalol) to blunt reflex ↑ HR & inotropy that would occur in response to vasodilators; verap/dilt if βB contraindic.

• Then ↓ SBP with IV vasodilators (eg, nitroprusside)

• HTN control may require multiple agents (median of 4 in one study; J Hum Hypertens 2005;19:227). If unable to control readily: 1st evaluate for complication (eg, visceral ischemia); Rx pain w/ MSO4; if no complication, then consider other drivers (eg, EtOH withdrawal).

• If HoTN: urgent surgical consultation, IVF to achieve euvolemia, pressors to keep MAP 70 mmHg; r/o complication (eg, tamponade, contained rupture, severe AI)

• Acute: all cases should be considered for emergent surgery

root replacement; valve sparing unless bicuspid or valve involvement

acute stroke should not necessarily dissuade from surgery (mortality w/o surgery ∼100%, Circ 2013;128:S175)

prior AoV surgery postulated to be protective from complications, but most would operate

need for preop coronary angio debatable as procedure nontrivial in setting of dissection and likelihood of performing concomitant CABG low

• Chronic: consider surgery if complicated by progression, AI or aneurysm

• Intervention warranted if complication (see below)

• Endovascular intervention (fenestrate flap to decompress false lumen, open occluded branch, stent entry tear) may be preferred over surgery due to possible ↓ mort. (JACC 2013;61:1661 & Circ 2015;131:1291)

• Stent graft for uncomplicated cases may ↓ risk of aorta-related complications and adverse remodeling (Circ Cardiovasc Interven 2013;6:407)

• Monitor all Pts w/ frequent assessment (sx, BP, UOP), pulse exam, labs (Cr, Hb, lactic acid), imaging (∼7 d or sooner if sx or significant lab Δ)

• Uncontrolled BP despite intensive IV Rx or continued or ↑ pain may indicate complication

• Progression: propagation of dissection, ↑ aneurysm size, ↑ false lumen size

• Rupture: pericardial sac → tamponade (avoid pericardiocentesis unless PEA); blood in pleural space, mediast., retroperitoneum; ↑ in hematoma on imaging portends rupture

• Malperfusion (partial or complete obstruction of branch artery)

can be static (avulsed/thrombosed) or dynamic (Δs in pressure in true vs false lumen)

coronary → MI (usually RCA → IMI, since dissection often along outer Ao curvature)

innominate/carotid → CVA, Horner

intercostal/lumbar → spinal cord ischemia/paraplegia

innominate/subclavian → upper extremity ischemia; iliac → lower extremity ischemia

celiac/mesenteric → bowel ischemia (can be subtle w/ nonspecific GI sx, anorexia, pain)

renal → acute renal failure or gradually ↑ Cr, refractory HTN

• AI: due to annular dilatation or disruption or displacement of leaflet by false lumen

• Mortality (Circ 2013;127:2031; JACC 2015;66:350)

∼50% prior to hospital

historically ∼1%/h × 48 h for acute prox AoD who survive to hospital w/ 47% subseq mort at 30 d; more recent data w/ 22% in-hospital mortality

13% at 30 d for acute distal overall but 25% if complications

mortality similar for proximal and distal that survive to discharge: ∼85% at 5 y

• Major concern is progression to aneurysm or recurrent dissection

• Treat BP, risk factors aggressively

• Serial imaging for all (CT or MRI, latter may be preferred to lower cumulative radiation exposure) at 1, 3, and 6 mo, and then annually (18 mo, 30 mo, etc.)

• Pts treated endovascularly need close follow-up to monitor for complication (eg, endoleak)

• Partial thrombosis of false lumen associated with worse outcomes/mortality (NEJM 2007;357:349)

• In patients who present at young age or other indications of predisposing factor, consider genetic evaluation and screening of family members

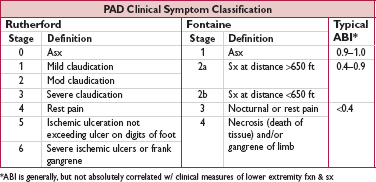

• Prev. ↑ w/ age: <1% if <40 y, ∼15% if ≥70 y; risk factors incl. smoking, DM, HTN, chol

• More frequent in Pts w/ other symptomatic atherosclerotic disease (eg, coronary, carotid)

• Associated w/ ↑ risk of CV events (JAMA 2007;297:1197)

• If sx, 3-y risk of stroke ∼3%, acute limb ischemia ∼4%, periph revasc ∼22% (Circ 2013;112:679)

• Asymptomatic (∼35%) or atypical sx (∼40%): often undertreated in terms of risk factor modifying therapy (Circ 2011;124;17)

• Claudication (∼25%): dull ache, often in calves

precip by walking & relieved by stopping (vs spinal stenosis, qv)

Leriche syndrome (aortoiliac occlusive disease): buttock & thigh claudication, ↓ or  femoral pulses, & erectile dysfxn

femoral pulses, & erectile dysfxn

• Critical limb ischemia (CLI, 1-2%): 1 or more of the following 3 manifestations

rest pain: ↑ w/ elevation b/c ↓ perfusion

ulcer: typically at pressure foci, often dry (in contrast, venous ulcers are more often at medial malleolus, wet, and with hemosiderin deposition)

gangrene: more typically “dry” (ie, distal limb, dry shrunken and dark red, lack of pus) as a manifestation of ischemia due to impaired blood flow rather than “wet” (ie, infected, pus present, fetid smell), which may occur in the setting of infection or injury

may be chronic (ie, sx >2-wk duration) vs acute limb ischemia, which is a vascular emergency (see below)

a/w poor outcome: 45% amputation & 20% mortality at 6 mo (J Vasc Surg 2000;31:S1)

• Blue toe syndrome: most likely atheroembolic disease with occlusion of digital arteries

• Ddx includes

nonvascular:

neurogenic claudication (spinal stenosis): pain w/ standing, relieved by sitting, lying, or forward flexion; a/w neurologic abnl (weakness, sensory Δs, h/o deg. disc disease)

musculoskeletal/arthritis: joint pain, morning stiffness, associated joint pathology or instability, crepitus or effusion

Baker’s cyst: posterior knee pain, knee stiffness, mass behind knee, discomfort w/ prolonged standing, impairment of bending

non-athero vascular:

venous claudication (uncommon): pain w/ walking in setting of proximal venous obstruction & no arterial obstruction

dissection, embolism, aneurysm, or vasculitis

popliteal artery entrapment (exercise-induced lower leg pain)

• Physical exam: ↓ peripheral pulses ± femoral bruits

if severe: pallor of feet w/ elevation, dependent rubor, cyanosis

other signs of chronic PAD: hair loss/shiny or cool skin, skin atrophy, nail hypertrophy

• Ankle:brachial index (ABI): nl 1–1.4; borderline 0.91–0.99; abnl ≤0.90; if >1.4, non-dx, likely due to calcified/noncompressible vessel

• Toe:brachial index (TBI) helpful if noncompressible (toe artery less likely to calcify); but ranges different than ABI (>0.7 nml, 0.5–0.7 mild, 0.35–0.5 mod, <0.35 mod–severe, severe if toe pressure <30 mmHg)

• Segmental pressures to determine level of disease (20 mmHg gradient between segments indicates stenosis)

• Pulse volume recording (PVR) done w/ segmental pressures: determine site and severity of disease. Abnormal waveform can indicate disease in noncompressible vessel, but pressures used over waveform if vessels are compressible.

• If  sx but nl ABI: ✓ exercise ABI (some consider even in asx Pt w/ risk factors for PAD if will modify therapy)

sx but nl ABI: ✓ exercise ABI (some consider even in asx Pt w/ risk factors for PAD if will modify therapy)

• Treadmill study (or 6-min walk test) to quantify magnitude of functional limitation

• Imaging (Duplex arterial U/S; CTA w/ distal run-off; MRA or angio) if dx in question or considering intervention. Some do routine Duplex U/S to monitor graft/stent patency.

• Treat risk factors: smoking cessation, high-intensity statin, control HTN & DM, smoking cessation (JACC 2010;56:2105). βB OK if indicated for another reason (eg, CAD, AF).

• Antiplatelet Rx: benefit shown primarily for ↓ CV risk (BMJ 2002;324;71) If asx: benefit of antiplt Rx unclear espec if ABI only borderline (JAMA 2010;303;9)

If sx: ASA or clopidogrel

ASA: 23% ↓ risk of major CV events seen in meta-analysis of older studies (mostly ASA but also other antiplatelet Rx) (BMJ 2002;324:71)

Clopidogrel: superior to ASA, but single, older study (Lancet 1996;348:1333)

ASA+clopi may be better than ASA alone, but only posthoc data (EHJ 2009;30:1992)

Vorapaxar (PAR-1 antag.) further ↓ risk on top of ASA or clopidogrel (Circ 2013;112:679)

• Anticoagulation w/ warfarin not beneficial (NEJM 2007;357:217)

• ACEI/ARB to ↓ CV risk (NEJM 2000;342:145)

• Improve claudication

Supervised exercise: sx-limited, ≥3×/wk, ≥30–45 min/session, ↑ as tolerated; beneficial including ↑ walking time 50–200% (Cochrane 2014;7:CD990); structured exercise more effective than home-based, but home-based still effective (JAMA 2013;310:57)

ACEI & statins may ↓ sx (Circ 2003;108:1481)

Cilostazol (nb, interacts w/ diltiazem & omeprazole; may cause headache or diarrhea; do not use in Pts w/ CHF); pentoxifylline likely less effective

• Limb preservation: foot exams for ulcers/wounds, revasc (qv), vorapaxar (PAR-1 antag) ↓ acute limb ischemia (Circ 2013;112:679), statin use assoc. w/ ↓ amput (EHJ 2014;35:2864)

• Consider if limiting sx despite exercise/medical Rx or if CLI; also consider as 1st-line Rx for isolated aortoiliac disease given high rate of long-term patency (Circ 2013;128:2704)

• Endovascular (angioplasty or stenting) usually favored over surgical (bypass or endarterectomy), but depends on lesion complexity & location (aortoiliac or “inflow” vs infrainguinal or “outflow”) and Pt comorbidities

• Decision for stent vs angioplasty alone depends on lesion length & complexity, location (eg, over joints) (J Vasc Surg 2007;33:S1)

• Angioplasty w/ paclitaxel-coated balloon associated with ↑ primary patency vs regular balloon for femoropopliteal disease (NEJM 2015;373:145)

• Durability of endovascular revascularization depends in part on location, with greater long-term patency for iliac vs femoral interventions (JACC 2006;47:e1)

• Dual antiplatelet (DAPT, ASA + clopidogrel) commonly prescribed after endovascular intervention for 1–3 mo, but no prospective data. DAPT after bypass surgery not beneficial overall but possibly in subgroup w/ prosthetic grafts (J Vasc Surg 2010;52:825).

• Anticoagulation with warfarin does not improve patency (NEJM 2007;357:217), but may be indicated in subgroups with high thrombotic risk

• Stents not ferromagnetic, so MRI safe, but both MRI & CT may have artifact. Duplex U/S useful to assess stent patency and is used by some for serial routine monitoring of stent or graft patency, even in asx Pts.

• If coronary angiography needed, avoid access through CFA stent or femoral bypass

• Sudden decrement in limb perfusion that threatens viability;

viable (no immed threat of tissue loss): audible art. Doppler signals, sensory & motor OK threatened (salvage requires prompt Rx): loss of arterial Doppler signal, sensory or motor

• Etiologies: embolism > acute thrombosis (eg, athero, APLA, HITT), trauma to artery

• Clinical manifestations (6 Ps): pain (distal to proximal, ↑ in severity), poikilothermia, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesias, paralysis

• Testing: thorough pulse & neuro exam; arterial Doppler; angiography, either CT w/ bilateral run-off through feet or arteriography

• Urgent consultation w/ vascular medicine and/or vascular surgery

• Treatment: immediate anticoagulation ± intra-arterial lytic; angioplasty or surgery

• Involving portions of carotid or vertebral arteries outside skull. Most commonly at carotid bifurcation but may involve common (CCA), internal (ICA), or external carotid (ECA).

• Most common etiology is athero; others include FMD, vasculitis, dissection, & radiation

• Associated w/ ↑ risk of systemic CV events including ipsilateral TIA/stroke

• Progressive narrowing, thrombosis or unstable plaque in CCA or ICA → embolization and/or ↓ distal perfusion → ischemia → TIA/stroke

• Asx chronically occluded vessel associated w/ low risk, as no embolization and Circle of Willis provides collateral flow

• Stenosis defined as % lumen diameter at most severe stenosis relative to either ICA, probable lumen diameter at site of stenosis, or proximal common carotid (J Neuroimaging 1994;4:222). Significant stenosis is >50%.

• Carotid bruit suggestive but not sensitive

• Duplex U/S: Se >80%, Sp ∼85%; 1st-line test

Peak systolic velocity (PSV) for severity

↑ end diastolic velocity (EDV), spectral broadening, carotid index (ratio of PSV in ICA vs CCA) and echolucent plaque each associated w/ ↑ risk

PSV >200 cm/s + EDV >140 cm/s + carotid index >4.5 has Se 96% for significant stenosis (Stroke 1996;27:1965; Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:1133)

• Transcranial Doppler (TCD) as adjunct to U/S may show severe stenosis, evidence of occlusion (collateral flow), or microemboli by high-intensity signal transients (HITS)

• If significant but nonsevere stenosis, repeat study at 6 mo to determine if stable and then annually thereafter

• If stenosis appears severe (≥70%) or requires further characterization, then either CT angio (Se ∼90%, Sp ≥95%) or MRA (Se ∼95%, Sp ≥95%). Caution with contrast & risk of either renal dysfxn (CTA) or nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (MRA).

• Angiography gold standard but invasive and assoc w/ risk of stroke

• Cause of <15% of strokes and risk <1% annually in Pts on standard med Rx (see below)

• General management

lifestyle intervention (smoking cessation, diet modification, exercise)

antiplatelet therapy: ASA 75–325 mg/d or clopidogrel 75 mg/d if ASA allergic (Circ 2011;124:354)

high-intensity statin (see “Lipids”) and BP control (see “HTN”)

• Revascularization (see options below) for selected Pts w/ ≥70% stenosis

older trials have shown ↓ stroke risk vs med Rx alone, but not compared to modern med Rx (NEJM 1993;328:221; JAMA 1995;273:1421; Lancet 2004;363:1491)

due to low rate of associated stroke, absolute risk reduction likely small and benefit of intervention debated

consider Pt preference, risk of procedure, overall life expectancy (eg, ≥5 y), gender (benefit less certain in women), lesion characteristics of ↑ stroke risk (eg, echolucent plaque, TCD evidence of microemboli)

• Symptomatic stenosis indicative of severe/unstable plaque and associated w/ ↑ risk of stroke. [∴ determination of sx important regarding treatment plan.

• Defined as recent (<6 mo) focal neurologic sx, sudden in onset, referable to carotid distribution. May include TIA or minor stroke [incl amaurosis fugax (transient monocular blindness)]. Vertigo & syncope unlikely related and generally not considered sx.

• For acute treatment for stroke, see “Stroke”

• All Pts w/ sx stenosis should receive med Rx as above

• Revascularization (NEJM 1991;325:445; Lancet 2004;363:915)

recommended for 70-99% stenosis, generally w/in 2 wk unless severe comorbidity w/ limited lifespan, severe ipsilateral stroke w/ persistent deficit, occluded carotid, or high operative risk (≥6%)

consider for 50-69% stenosis, depending on Pt-specific factors

not indicated if <50% stenosis

• Carotid endarterectomy (CEA): gold standard. Risk of procedural stroke or death <3% for asymptomatic disease and <6% for sx disease in experienced centers.

• Carotid artery stenting (CAS; JACC 2014;64:722): compared w/ CEA, periprocedural risk of stroke ↑ (espec in elderly) & MI ↓ (although many asx), subsequent rates of stroke similar (NEJM 2010;363:11; Lancet 2010;376:1062). Consider if not surgical candidate (anatomy or comorbidities). Generally requires DAPT (ASA + clopidogrel) for 30 d.

• Cerebral and basilar arteries and distal branches thereof

• Most common etiology is athero & assoc w/ traditional athero risk factors (Circ 2014;1407:14); others include: dissection, FMD, vasoconstriction, vasculitis, moyamoya

• Estimated to cause 5–10% of ischemic strokes and more prevalent among blacks, Hispanics and Asians (Stroke 1995;26:14)

• Diagnosis: MRA, CTA, or TCD vs angio (see above); duplex U/S not useful

• Medical treatment similar as in extracranial; however, consider ASA+clopidogrel for sx disease for 90 d (NEJM 2011;365:993)

• Stenting and intracranial bypass not shown to be beneficial and not routinely recommended (NEJM 2011;365:993; JAMA 2015;313:1240)

• In general monotherapy preferred to multiagent therapy for long-term prevention due to ↑ ICH risk w/ multiagent therapy

• ASA: ↓ death & repeat stroke; equal to warfarin in nonembolic stroke (NEJM 2001;345:1444)

• Clopidogrel: marginally superior to ASA, slightly ↑ ICH (Lancet 1996:348:1329)

• Multiagent antiplatelet therapy:

ASA + clopi: not more effective than ASA alone and ↑ bleeding & ICH (Lancet 2004;364:331; NEJM 2012;367:817). In minor stroke/TIA, ASA + clopi × 21 d → clopi monoRx vs ASA monoRx resulted in ↓ stroke w/o ↑ ICH (NEJM 2013;369:11).

ASA + dipyrimadole: superior to ASA (Lancet 2006;367:1665), but ↑ ICH and poor compliance

Addition of vorapaxar to ASA or ASA+clopi ↓ first stroke in Pts w/ athero, but contra-indicated in patients w/ prior stroke due to ICH risk (NEJM 2012;366:1404; Stroke 2013;691:8)

• Not routinely indicated. Anticoag if cardiac/paradoxical emboli (except bacterial endocarditis) or hypercoag state. See “AF” and “VTE” for details.

• Hold off on anticoag in large strokes for ∼2–4 wk given risk of hemorrhagic conversion.

• BP (see “HTN”): long-term SBP target 120–139 mmHg (JAMA 2011;306:2137)

• LDL: high-intensity statin therapy (Circ 2014;129 (Suppl 2):S1)

• May involve intracranial or extracranial arteries. Manifests as luminal stenosis, thrombo-embolism or aneurysm. ∼20% of ischemic strokes in young Pts (primarily embolic).

• Etiologies: trauma, physical activity, ? neck manip.; can be spontaneous (if assoc cond.)

• FMD most common assoc. condition (seen in 15–20%). Others infrequent: vascular EDS, Marfan, osteogenesis imperfect, homocystinuria, PKD, α1-AT.

• Most (>60%) report HA or neck pain, Horner’s in ∼25%, tinnitus, rarely eye pain

• Imaging may show “crescent sign” of hematoma, string sign, tapering stenosis, flap or dissected aneurysm. Duplex U/S can be initial screen but lower Se (68–95%) and limited utility at skull base. CTA & MRA w/ similar Se & Sp; angio if inconclusive noninvasive imaging.

• Treatment: if stroke, see “Stroke.” In general, thrombolysis should not be withheld if indicated. If SAH, manage accordingly.

• Antithrombotic therapy: either anticoagulation (AC) or antiplatelet Rx may be considered for extracranial dissection; however, large meta-analysis showed no benefit of AC over antiplatelet Rx (Neurology 2012;79:686). If AC chosen, typically for 3–6 mo, then Δ to antiplatelet. Intracranial dissection treated with antiplatelet monotherapy and not AC.

• Endovascular therapy or surgery considered for selected Pts, particularly if recurrent ischemia; however, no trials to demonstrate benefit.

• ↑ stroke risk: ≥4-mm separation, R → L shunting at rest, ↑ septal mobility, atrial septal aneurysm

• If PFO & stroke/TIA: no benefit of warfarin over ASA (Circ 2002;105:2625), but consider if at high risk for or has DVT/PE. No sig benefit shown for PFO closure so far, albeit studies small & w/ favorable trends (NEJM 2012;366:991; 2013:1083 & 1092).

• Prevalence of saccular aneurysms 3.2%, w/ equal sex ratio (Lancet Neurol 2011;10:626); 20–30% having >1 aneurysm

• Associated with family hx, hereditary syndromes (eg, EDS, polycystic kidney), smoking, HTN, aortic coarctation, ? estrogen deficiency (female preponderance after menopause) (Stroke 2001;32:606)

• Clinical presentations: most commonly incidental finding on brain imaging

may be found in those presenting with SAH, which typically presents as “worst headache of my life,” ± syncope, nausea, vomiting, meningismus (Neurology 1986;36:1445)

rarely unruptured aneurysms become symptomatic (eg, headache, visual change, cranial neuropathy, facial pain)

• Diagnosis: CTA or MRA

• Instruct Pt to avoid smoking, heavy EtOH use, illicit drugs, straining/Valsalva

• Treatment requires consideration of size, location, Pt age and comorbidities. In general:

if sx or SAH → repair

if no sx/SAH and ≥7–10 mm, consider repair

if <7 mm observe (CTA or MRA q6mo and every 2–3 y once showing no Δ)

endovascular coiling ↓ periprocedural morbidity & mortality vs surgical clipping, but ↑ risk of recurrence

• Rare (<1% of arterial aneurysms) (Surgery 1983;93:319)

• True aneurysm may be associated with athero, trauma, dissection (qv), infection, vasculitis or radiation. Male:female predominance (2:1).

• Infected pseudoaneurysm may occur at site of prior carotid intervention.

• Clinical presentation: TIA/stroke; less likely mass effect or rupture

• Diagnosis: see approach for carotid disease above

• Instruct Pt to avoid smoking, heavy EtOH use, illicit drugs, straining/Valsalva

• Treatment: sx disease should be repaired; consider repair if asx and >2 cm, w/ thrombus, or ≤2 cm but ↑’ing. Surgical and endovascular options depending on anatomy & Pt risk.

• Uncommon (<2/100,000/yr); female predominance (3× more common)

• >85% w/ risk factor including: hypercoagulable state, OCP, pregnancy, malignancy, infection, prior trauma, vasculitis, other inflammatory states (eg, IBD), hematologic disorders, nephrotic syndrome

• Clinical presentation variable and includes HA (∼90%), seizure, focal deficits, encephalopathy, sx of isolated intracranial hypertension (HA ± vomiting, papilledema, visual problems) may occur if hemorrhage or edema

• Diagnose w/ MR venography or CT venography (traditional head CT normal in ∼30% of CVT). D-dimer may be elevated but does not reliably exclude.

• Acute treatment

treat elevated ICP

consider antiseizure Rx if seizure on presentation or otherwise high risk

anticoagulation (UFH or LMWH; see VTE for dosing) if no contraindication (nb, presence of ICH not absolute contraindication)

consider endovascular venous recanalization with direct thrombolysis if progressive neurologic worsening despite anticoagulation

• Chronic treatment

anticoagulation w/ VKA w/ INR 2–3 for 3–6 mo if provoked or 6–12 if unprovoked

consider indefinite duration if recurrent, complicated by DVT or PE, or severe thrombophilia

if occurred in setting of OCP, change to nonestrogen-based contraception

• Monitoring: imaging at 3–6 mo after dx to assess for recanalization

• Superficial thrombophlebitis: pain, tenderness, erythema along superficial vein

• Deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

Proximal: thrombosis of iliac, femoral, or popliteal veins (nb, “superficial” femoral vein part of deep venous system)

Distal: calf veins below knee; lower risk of PE/death than prox (Thromb Haem 2009;102:493)

• Pulmonary embolism (PE): thrombosis originating in venous system and embolizing to pulmonary arterial circulation; 1 case/1000 person y; 250,000/y (Archives 2003;163:1711)

• Virchow’s triad for thrombogenesis

stasis: bed rest, inactivity, CHF, CVA w/in 3 mo, air travel >6 h (NEJM 2001;345:779)

injury to endothelium: trauma, surgery, prior DVT, inflammation, central catheter

thrombophilia: APC resistance, protein C or S deficiency, APS, prothrombin gene mutation,↑ factor VIII, hyperhomocysteinemia, HIT, OCP, HRT, tamoxifen, raloxifene

• Malignancy (12% of “idiopathic” DVT/PE)

• History of thrombosis (greater risk of recurrent VTE than genetic thrombophilia)

• Obesity, smoking, acute infection, postpartum (JAMA 1997;277:642; Circ 2012;125:2092)

• Statin therapy ↓ risk (NEJM 2009;360:1851)

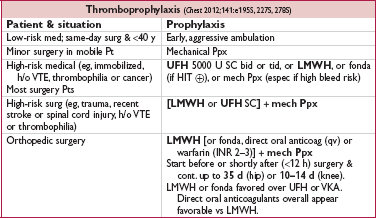

For enoxaparin, 30 mg bid for highest risk or 40 mg qd for moderate risk or spinal/epidural anesth. Dose adjust: qd in CrCl <30 mL/min, ↑ 30% if BMI >40 (Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:1064).

• Direct oral anticoagulants vs LMWH (Annals 2012;156:710)

Dabigatran (approved in Europe & Canada; 110 mg 1–4 h after surgery & hemostasis or 220 mg if not initiated on day of surgery; 220 mg qd maintenance) noninferior to LMWH after hip and knee surgery (Lancet 2007;370:949)

Rivaroxaban (10 mg qd 6–10 h postop) ↓ VTE by ∼25–50% vs enox 40 mg qd, with ≈ bleeding after hip or knee replacement (NEJM 2008;358:2765 & 2776; Lancet 2009;373:1673)

Apixaban (2.5 mg bid 12–24 h postop) ↓ VTE by ∼50% vs enox 40 mg qd, with ≈ bleeding after hip replacement (NEJM 2010;363:2487)

Edoxaban (30 mg qd 6-24 h after surgery) ↓ VTE vs enox 20 mg qd, but no comparison to standard dose enox (Thromb Res 2014;134:1198)

• Evolving role for Ppx in ambulatory cancer Pts w/ low bleeding risk and additional VTE risk factors (NEJM 2012;366:601). Khorana score (cancer site, plt & WBC counts, Hb, BMI) risk predictor (Blood 2008;111:4902). Semuloparin (ultra LMWH) ↓ VTE by ∼2/3 w/o ↑ major bleeding in Pts w/ met. or locally adv. cancer receiving chemo (NEJM 2012;366:601).

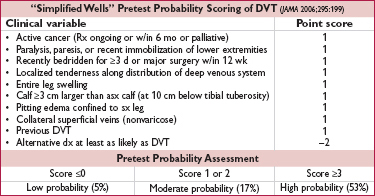

• Calf pain, swelling (>3 cm c/w unaffected side), venous distention, erythema, warmth, tenderness, palpable cord,  Homan’s sign (calf pain on dorsiflexion, seen in <5%)

Homan’s sign (calf pain on dorsiflexion, seen in <5%)

• Phlegmasia cerulea dolens: massive proximal DVT → stagnant blood → edema, cyanosis, pain, compartment syndrome → can lead to limb loss or death

• 50% of Pts with sx DVT have asx PE

• Palpable tender superficial veins c/w superficial thrombophlebitis rather than DVT

• Popliteal (Baker’s) cyst: related to knee pathology, may result in calf pain & may lead to DVT due to compression of popliteal vein

• For UE DVT, +1 point each for venous cath, local pain, & unilateral edema, –1 if alternative dx. ≤1 = unlikely; ≥2 = likely. U/S if likely or if unlikely but abnl D-dimer (Annals 2014;160:451).

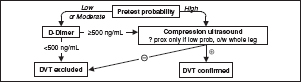

• D-dimer: <500 helps r/o; ? use 1000 as threshold if low risk (Annals 2013;158:93)

• Compression U/S >95% Se & Sp for sx DVT (lower for asx DVT); survey whole leg rather than just proximal if ≥mod prob (JAMA 2010;303:438); venography rarely used

Figure 1-5 Approach to suspected DVT (Chest 2012;141:e351S)

• Dyspnea (73%), pleuritic chest pain (66%), cough (37%), hemoptysis (13%)

• ↑ RR (>70%), crackles (51%), ↑ HR (30%), fever, cyanosis, pleural friction rub, loud P2

• Massive: syncope, HoTN, PEA; ↑ JVP, R-sided S3, Graham Steell (PR) murmur

• CXR (limited Se & Sp): 12% nl, atelectasis, effusion, ↑ hemidiaphragm, Hampton hump (wedge-shaped density abutting pleura); Westermark sign (avascularity distal to PE)

• ECG (limited Se & Sp): sinus tachycardia, AF; signs of RV strain → RAD, P pulmonale, RBBB, SIQIIITIII & TWI V1–V4 (McGinn-White pattern; Chest 1997;111:537)

• ABG: hypoxemia, hypocapnia, respiratory alkalosis, ↑ A-a gradient (Chest 1996;109:78), 18% w/ room air PaO2 85–105 mmHg, 6% w/ nl A-a gradient (Chest 1991;100:598)

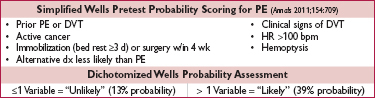

• D-dimer (JAMA 2015;313:1668): high Se, poor Sp (∼25%);  ELISA has >99% NPV [∴ use to r/o PE if “unlikely” pretest prob. (JAMA 2006;295:172)

ELISA has >99% NPV [∴ use to r/o PE if “unlikely” pretest prob. (JAMA 2006;295:172)

consider age-specific cutpoint: 500 if <50 y, 10× age if ≥50 y (JAMA 2014;311:1117)

• Echocardiography: useful for risk stratification (RV dysfxn), but not dx (Se <50%)

• V/Q scan: high Se (∼98%), low Sp (∼10%). Sp improves to 97% for high prob VQ. Use if pretest prob of PE high and CT not available or contraindicated. Can also exclude PE if low pretest prob, low prob VQ, but 4% false  (JAMA 1990;263:2753).

(JAMA 1990;263:2753).

• CT angiography (CTA; see Radiology inserts; JAMA 2015;314:74): Se ∼90% & Sp ∼95% w/ MDCT (NEJM 2006;354:2317); PPV & NPV >95% if imaging concordant w/ clinical suspicion, ≤80% if discordant ([∴ need to consider both); CT may also provide other dx

• Lower extremity compression U/S shows DVT in ∼9%, sparing CTA, but when added to CTA, does not Δ outcomes (Lancet 2008;371:1343)

• Pulmonary angio: ? gold standard (morbidity 5%, mortality <0.5%), infrequently performed

• MR angiography: Se 84% (segmental) to 100% (lobar) (Lancet 2002;359:1643); if add MR venography, Se 92%, Sp 96% (Annals 2010;152:434)

Figure 1-6 Approach to suspected PE using CTA

Based on data from NEJM 2005;352:1760 & 2006;354:22; JAMA 2005;293:2012 & 2006;295:172

• Thrombophilia workup: ✓ if  FH, may be helpful but consider timing as thrombus, heparin and warfarin Δ results. May not be helpful for Pt if will not change management (eg, plan for long-term anticoagulation regardless), although could be of use to relatives (JAMA 2005;293:2352; Blood 2008;112:4432; Am J Med 2008;121:458).

FH, may be helpful but consider timing as thrombus, heparin and warfarin Δ results. May not be helpful for Pt if will not change management (eg, plan for long-term anticoagulation regardless), although could be of use to relatives (JAMA 2005;293:2352; Blood 2008;112:4432; Am J Med 2008;121:458).

• Malignancy workup: 12% Pts w/ “idiopathic” DVT/PE will have malignancy; age-appropriate screening adequate; avoid extensive w/u (NEJM 1998;338:1169 & 2015;373:697)

• Clinical: hypotension and/or tachycardia (∼30% mortality), hypoxemia

• CTA: RV / LV dimension ratio >0.9 (Circ 2004;110:3276)

• Biomarkers: ↑ troponin & ↑ BNP a/w ↑ mortality; w/  Tn, decomp extremely unlikely (Circ 2002;106:1263 & 2003;107:1576; Chest 2015;147:685)

Tn, decomp extremely unlikely (Circ 2002;106:1263 & 2003;107:1576; Chest 2015;147:685)

• Echocardiogram: RV dysfxn (even if normal troponin) (Chest 2013;144:1539)

• Simplified PE Severity Index: 0 RFs → 1.1% mort.; ≥1 → 8.9% mort (Archives 2010;170:1383)

RFs: age >80 y; h/o cancer; h/o HF or lung disease; HR ≥110; SBP <100; SaO2 <90%

• Superficial venous thrombosis: elevate extremity, warm compresses, compression stockings, NSAIDs for sx. Anticoag if high risk for DVT (eg, ≥5 cm, proximity to deep vein ≤5 cm, other risk factors) for 4 wk as ∼10% have VTE w/in 3 mo (Annals 2010;152:218).

• LE DVT: proximal → anticoag. If distal: anticoag if severe sx, o/w consider serial imaging over 2 wk and anticoag if extends (although if bleeding risk low, many would anticoag).

• UE DVT: anticoagulate (same guidelines as LE; NEJM 2011;364:861). If catheter-associated, need not remove if catheter functional and ongoing need for catheter.

• PE: anticoagulate

• Initiate immediately if high clinical suspicion or intermed but dx test results delayed for ≥4 h

• Either (a) initial parenteral anticoag → long-term oral anticoagulant (eg, warfarin or Xa inhibitor) or (b) solely with an oral Xa inhibitor

• LMWH (eg, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg SC bid or dalteparin 200 IU/kg SC qd)

Preferred over UFH (espec in cancer) except: renal failure (CrCl <25), ? extreme obesity, hemodynamic instability or bleed risk (Cochrane 2004;CD001100)

No need to monitor anti-factor Xa unless concern re: dosing (eg, renal insuffic.)

Attractive option as outPt bridge to long-term oral anticoagulation

• If cancer, LMWH ↓ recur. & mort. c/w UFH & warfarin (NEJM 2003;349:146; Lancet Oncol 2008;9:577; JAMA 2015;314:677); ✓ head CT for brain mets if melanoma, renal, thyroid, chorioCA

• Fondaparinux: 5–10 mg SC qd (NEJM 2003;349:1695); use if HIT  ; avoid if renal failure

; avoid if renal failure

• DVT & low-risk PE can be treated completely as outPt (Lancet 2011;378:41)

• IV UFH: 80 U/kg bolus → 18 U/kg/h → titrate to PTT 1.5–2.3 × cntl (eg, 60–85 sec); preferred option when contemplating thrombolysis or catheter-based Rx (qv)

• IV Direct thrombin inhibitors (eg, argatroban, lepirudin) used in HIT  Pts

Pts

• Warfarin (goal INR 2–3): start same day as parenteral anticoag unless instability and ? need for lytic, catheter-based Rx or surgery; overlap ≥5 d w/ parenteral anticoag & until INR ≥2 × ≥24 h

• Oral Xa inhibitor: effect wears off w/in 24 h, but not easily immediately reversed

Can give as sole anticoag (nb, initial doses higher than for AF): rivaroxaban (15 mg bid for 1st 3 wk → 20 mg/d) as good/better than LMWH → warfarin in preventing recurrent VTE, ↓ bleeding (NEJM 2010;363:2499 & 2012;366:1287); apixaban (10 mg bid × 7 d → 5 bid) ≈ LMWH → warfarin in preventing recurrent VTE, ↓ bleeding (NEJM 2013;369:799)

Can initiate after ≥5 d of parenteral anticoag (1st dose when d/c IV UFH or w/in 2 h before when next LMWH dose would have been due): both dabigatran (150 mg bid) & edoxaban (60 mg qd) ≈ warfarin but w/ ↓ bleeding (NEJM 2009;361:2342 & 2013;369:1406)

• Typically TPA 100 mg over 2 h or wt-adjusted TNK bolus

• Indications & efficacy below; risk of ICH ∼1.5%, ↑ w/ age; see contraindications in “ACS”

• Massive PE (hemodynamic compromise): ↓ death and recurrent PE each by ∼50% (Circ 2004;110:744; JAMA 2014;311:2414; EHJ 2015;36:605) & lower PVR long term (JACC 1990;15:65)

• Submassive PE (hemodyn. stable but RV dysfxn on echo or enlargement on CTA, or ? marked dyspnea or severe hypoxemia): ↓ death & ↑ bleeding; may consider if low bleed risk (see lytic contra-indic.; EHJ 2015;36:605). Benefit/risk may be more favorable if <75 y (NEJM 2014;370:1402; JAMA 2014;311;2414). Some centers prefer catheter-directed Rx (qv).

• Moderate PE w/ large clot burden (≥2 lobar arteries or main artery on CT or high prob VQ w/ ≥2 lobes w/ mismatch): low-dose lytic (50 mg if ≥50 kg or 0.5 mg/kg if <50 kg; for both 10 mg bolus → remainder over 2 h) ↓ pulm HTN w/ ≈ bleeding vs heparin alone; await further validation (Am J Cardiol 2013;111:273)

• DVT: consider if all are present (a) acute (<14 d) & extensive (eg, iliofemoral), (b) severe symptomatic swelling or ischemia (phlegmasia cerulea dolens), (c) catheter-directed Rx not available, and (d) low bleeding risk

• Catheter-directed therapy (fibrinolytic & thrombus fragmentation/aspiration)

Consider if extensive DVT (see above) and to ↓ post-thrombotic synd (Lancet 2012;379:31)

Consider if PE w/ hemodyn. compromise or high risk & not candidate for systemic lysis or surgical thrombectomy (Circ 2011;124:2139). Preferred to systemic lytic by some centers.

U/S-assisted → improves hemodynamics & RV fxn vs anticoag alone (EHJ 2015;36:597)

• Thrombectomy: if large, proximal PE + hemodynamic compromise + contra. to lysis; consider in experienced ctr if large prox. PE + RV dysfxn (J Thorac CV Surg 2005;129:1018)

• IVC filter: use instead of anticoagulation if latter contraindicated

No benefit to adding to anticoag (including in submassive) (JAMA 2015;313:1627)

Consider removable filter for temporary indications

Complications: migration, acute DVT, ↑ risk of recurrent DVT & IVC obstruction (5–18%), which may lead to worsening LE sx (Archives 1992;152:1985)

• Superficial venous thrombosis: 4 wk

• 1st prox DVT or PE 2° reversible/time-limited risk factor or distal DVT: 3–6 mo

• 1st unprovoked prox DVT/ PE: ≥3 mo, then reassess; benefit to prolonged Rx (see below). Consider bleeding risk, Pt preference and intensity of extended Rx.

• 2nd VTE event or cancer: indefinite (or until cancer cured) (NEJM 1997;336:393 & 2003;348:1425)

• Does not appear that can rely on D-dimer testing to guide d/c (Annals 2015;162:27)

• After ≥6 mo of anticoag, following strategies have been compared w/ no extended Rx:

• Full-dose dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban: 80–90% ↓ recurrent VTE, 2–5× bleeding, but no signif excess in major bleeding (NEJM 2010;363:2499; 2013;368:699 & 709)

• Full-dose warfarin: 85% ↓ reduction in recurrent VTE (JAMA 2015;314:31)

• Low-intensity warfarin (INR 1.5–2.0): 64% ↓ reduction in recurrent VTE (NEJM 2003;348:1425)

• Low-intensity apixa (2.5 mg bid): 80% ↓ recur. VTE, w/o signif ↑ bleeding (NEJM 2013;368:699)

• Aspirin: 32% ↓ recurrent VTE (NEJM 2012;366:1959 & 367:1979)

• Early ambulation

• For DVT: fitted graduated compression stockings (min 20–30 mmHg → 30–40 mmHg) for sx & to ↓ risk of postthrombotic synd (occurs in 23-60%; J Thromb Thrombolysis 2009;28:465)

• Leg elevation and exercise (use of calf muscle pump) also may be helpful

• Anticoag teaching: avoidance of high-risk activities, med alert bracelet, dietary instructions

• Post-thrombotic syndrome (23–60%): thrombosis → injury to vein/valves → pain, edema, venous ulcers (J Thromb Thrombolysis 2009;28:465)

• Recurrent VTE: 1%/y (after 1st VTE) to 5%/y (after recurrent VTE)

after only 6 mo of Rx: 5%/y & >10%/y, respectively

predictors: abnl D-dimer 1 mo after d/c anticoag (NEJM 2006;355:1780);  U/S after 3 mo of anticoag (Annals 2002;137:955); thrombin generation >400 nM (JAMA 2006;296:397)

U/S after 3 mo of anticoag (Annals 2002;137:955); thrombin generation >400 nM (JAMA 2006;296:397)

• Chronic thromboembolic PHT after acute PE ∼3.8% (NEJM 2004;350:2257), consider thromboendarterectomy

• Mortality: ∼10% for DVT and ∼10–15% for PE at 3–6 mo (Circ 2008;117:1711)

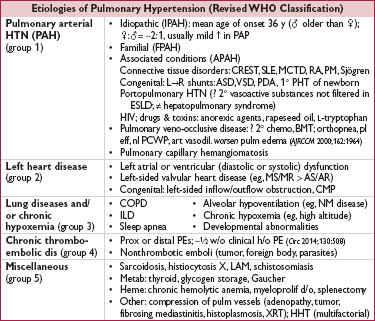

PA mean pressure ≥25 mmHg at rest

• Smooth muscle & endothelial cell proliferation; mutations in bone morphogenic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) in ∼50% familial & ∼26% sporadic cases of IPAH (NEJM 2001;345:319)

• Imbalance between vasoconstrictors and vasodilators

↑ vasoconstrictors: thromboxane A2 (TXA2), serotonin (5-HT), endothelin-1 (ET-1)

↓ vasodilators: prostacyclin (PGI2), nitric oxide (NO), vasoactive peptide (VIP)

• In situ thrombosis: ↑ TXA2, 5-HT, PAI-1; ↓ PGI2, NO, VIP, tissue plasminogen activator

(Circ 2013;62:25S)

• Dyspnea, exertional syncope (hypoxia, ↓ CO), exertional chest pain (RV ischemia)

• Symptoms of R-sided CHF (eg, peripheral edema, RUQ fullness, abdominal distention)

• WHO class: I = asx w/ ordinary activity; II = sx w/ ord. activ.; III = sx w/ min activ.; IV = sx at rest

• PHT: prominent P2, R-sided S4, RV heave, PA tap & flow murmur, PR (Graham Steell), TR

• ± RV failure: ↑ JVP, hepatomegaly, peripheral edema

• IPAH yearly incidence 1–2 per million, [∴ r/o 2° causes

• High-res chest CT: dil. & pruning of pulm arteries, ↑ RA and RV; r/o parenchymal lung dis.

• ECG: RAD, RBBB, RAE (“P pulmonale”), RVH (Se 55%, Sp 70%)

• PFTs: disproportionate ↓ DLco, mild restrictive pattern; r/o obstructive & restrict. lung dis.

• ABG & polysomnography: ↓ PaO2 and SaO2 (espec w/ exertion), ↓ PaCO2, ↑ A-a gradient; r/o hypoventilation and OSA

• TTE: ↑ RVSP (but estimate over/under by ≥10 mmHg in 1⁄2 of PHT Pts; Chest 2011;139:988)

↑ RA, RV (RV:LV area >1) and PA size; TR, PR

↑ RVSP → interventricular septum systolic flattening (“D” shape)

↑ RAP → interatrial septum bowing into LA

↓ RV systolic fxn: TAPSE (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion) <1.6 cm; lateral-septal tissue-Doppler imaging disparity (reflecting relatively more systolic dysfxn of RV lateral wall vs septum, which is shared with LV)

↑ PA impedance → RVOT Doppler notching

r/o LV dysfxn, MV or AoV disease, and congenital heart disease

• RHC: ↑ RA, RV, & PA pressures; ✓ L-sided pressures and for shunt

if PAH: nl PCWP, ↑ transpulm gradient (mean PAP-PCWP >12–15), ↑ PVR, ± ↓ CO

if 2° to L-heart disease: PCWP (or LVEDP) >15; if PVR nl → “passive PHT”; PVR >240 suggests mixed picture: if ↓ PCWP → ↓ PVR, then “reactive” PHT; if no Δ, then “fixed”

• CTA (large/med vessel), V/Q scan (small vessel to r/o CTEPH), ± pulmonary angiogram: r/o PE and chronic thromboembolic disease

• Vasculitis labs: ANA (∼40%  in PAH), RF, anti-Scl-70, anticentromere, ESR

in PAH), RF, anti-Scl-70, anticentromere, ESR

• LFTs & HIV: r/o portopulmonary and HIV-associated PAH

• 6-min walk test (6MWT) or cardiopulmonary exercise testing to establish fxnl capacity

• Principles

1) prevent and reverse vasoactive substance imbalance and vascular remodeling

2) prevent RV failure: ↓ wall stress (↓ PVR, PAP, RV diam); ensure adeq. systemic DBP

• Supportive

Oxygen: maintain SaO2 >90–92% (reduces vasoconstriction)

Diuretics: ↓ RV wall stress and relieve RHF sx; gentle b/c RV is preload dependent

Digoxin: control AF, ? counteract neg. inotropic effects CCB

Dobutamine and inhaled NO or prostacyclin for decompensated PHT

Anticoagulation: ↓ VTE risk of RHF; ? prevention of in situ microthrombi; ? mortality benefit even if in NSR, no RCTs (Circ 1984;70:580; Chest 2006;130:545)

Supervised exercise training (Eur Respir J 2012;40:84)

• Vasodilators (right heart catheterization prior to initiation) acute vasoreactivity test: use inhaled NO, adenosine or prostacyclin to identify Pts likely to have a long-term response to oral CCB ( vasoreactive response defined as ↓ PAP ≥10 mmHg to a level <40 mmHg with ↑ or stable CO); ∼10% Pts are acute responders; no response → still candidates for other vasodilators (NEJM 2004;351:1425)

vasoreactive response defined as ↓ PAP ≥10 mmHg to a level <40 mmHg with ↑ or stable CO); ∼10% Pts are acute responders; no response → still candidates for other vasodilators (NEJM 2004;351:1425)

• Up front combination Rx (tadalafil + ambrisentan vs monotherapy): ↓ sx, ↓ NT-BNP, ↑ 6MWT, ↓ hospitalizations (NEJM 2015;373:834)

• Treat underlying causes of 2° PHT; can use vasodilators, although little evidence beyond riociguat use for CTEPH as described above

• Refractory PHT:

balloon atrial septostomy: R→L shunt causes ↑ CO, ↓ SaO2, net ↑ tissue O2 delivery

lung transplant (single or bilateral); heart-lung needed if Eisenmenger physiology

Figure 1-7 Treatment of PAH (modified from JACC 2009;54:S78)

• Avoid overly aggressive volume resuscitation

• Caution with vasodilators if any L-sided dysfunction

• May benefit from inotropes/chronotropes

• Mechanical RV support (RVAD, ECMO) (Circ 2015;132:526)

• Consider fibrinolysis if acute, refractory decompensation (eg, TPA 100 mg over 2 h)

• Median survival after dx ∼2.8 y; PAH (all etiologies): 2-y 66%, 5-y 48% (Chest 2004;126:78-S)

• Poor prognostic factors: clinical evidence of RV failure, rapidly progressive sx, WHO (modified NYHA) class IV, 6MWT <300 m, peak VO2 <10.4 mL/kg/min, ↑ RA or RV or RV dysfxn, RA >20 or CI <2.0, ↑ BNP (Chest 2006;129:1313)

• Lung transplant: 1-y survival 66–75%; 5-y survival 45–55% (Chest 2004;126:63-S)